1. Introduction: Questions around the Cult of Our Lady of Fátima

Fátima is one of the most popular Catholic pilgrimage sites next to Rome and Lourdes. A formerly small village about one hour north of Lisbon, the place and its meaning has seen some radical changes since three small children had reported an apparition of Mary, the mother of Jesus, in May 1917 (

Vilaça 2018). Since then, Fátima has not only attracted millions of pilgrims from all over the world, but the cult of this Madonna, and statues representing her, have spread around the world.

The veneration of Our Lady of Fátima has received particular support by the popes of the 20th century, starting with Pius XI. This is continuing today. When Pope Francis dedicated Ukraine and Russia to the Immaculate Heart of “Our Lady of Peace” on 25 March 2022, and asked all bishops around the world to follow his example, he referred to one of the “three secrets” of Fátima and prayed at the foot of the original statue of Our Lady of Fátima. According to the “secret”, the Mother of God, according to the surviving seer (two of the three children died soon after the apparition because of the Flu Pandemic of 1917–1919), had asked to dedicate Russia to the Immaculate Heart of Mary in order to bring peace to the world (

https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/popes-peace-prayer-ukraine-recalls-ancient-prophesy-83667038 (accessed on 15 September 2022)). This message became known in the early 1940s and led to the creation of a number of anti-communist groups, namely the “Blue Army of Our Lady of Fátima” in the United States, Australia, and in other countries. (

O’Connor 2022; for Australia:

Massam 1991; Canada:

Gareau 2020). According to their own narrative, the Blue Army’s pledge (to dedicate one’s life to the spreading of the message of Fátima all over the world) was drafted by the founder, the American Haffert, together with Sister Lucia herself (

Bennett 2015). Further on, in the late 20th and early 21st century, the pilgrimage site and the cult as such had become linked to immigration to Portugal, and to the tourism boom of the last decades (

Vilaça 2018).

All of this gives testimony of a transnational cult that is at the same time global, national, and local. It is a ritualistic adoration of symbolic stories and objects in which millions of people participate. How do we explain the success of this cult in a society where secularism and clericalism have often clashed? How did this national, at times even nationalist, cult become a global cult? What role did Portuguese colonialism and migration play in this? Finally, what does its history tell us about the complex relationship between a secularizing and pluralizing society and a cult that has its roots in what has been described as the “

civilização paroquial” (a civilization built around the Catholic parish in a mostly rural setting) (

Coutinho 2020), which has almost vanished since the 1960s? (Similar questions have been posed by:

Blackbourn 1993.)

The question of the role of the Catholic church in the country has caused major political and social conflicts since the early 19th century when radical French secularist and revolutionary ideas first arrived. This conflict had broken out again when a republican revolution brought down the monarchy in 1910. Some of the republican parties and politicians, which suffered from a lack of legitimacy because they were mostly based among the urban upper and middle classes in a mostly rural country, had applied an aggressive anti-clerical program that included restrictions of the freedom of religion, arrests of priests and bishops and similar actions which caused widespread anxiety among the rural, often illiterate, masses of northern Portugal. Desperate attempts to follow the example of the secularist French Republic deepened the conflict, such as the introduction of the law separating church and state in 1911, which represented the climax of a series of anti-clerical decrees and laws which had targeted religious orders (suppression and confiscation of their property), religious marriage (legalization of divorce), religious education, and even banned the wearing of the cassock in the street and the ringing of church bells. All this had created not only anxiety and a sense of loss among a large part of the rural masses, but it also strengthened their resilience and hopes for a sign from heaven in support of their faith (

Bennett 2012b;

Dix 2008). However, for most believers, the apparition of the Holy Mother of God had mostly personal, social, or familial meanings (

Maunder 2016).

In this context, the conflict with the urban educated elites was further aggravated when the parliament, which represented a small elite, decided to support the French republic and the Allies in the Great War, sending very badly trained troops into the battles on the Western front. This was a war that most of the peasantry did not support and it resulted in about 20,000 casualties, of which 8000 were dead. Many families around Fátima, including the families of the seers, were afraid that their sons would have to serve in the war in 1917.

2. The Apparitions of 1917

In this context, it is easier to understand what happened in Fátima, a small area of land dedicated to the grassing of sheep, near a few small villages in Central Portugal in 1917. The sociologist Jeffrey S Bennett has provided an analysis of the early cult and how different actors became involved with it and created it as a long-lasting, deeply rooted social phenomenon around the area where the apparitions first occurred in May 1917 (

Bennett 2012a).

When three young children, 8, 10, and 11 years old, claimed that they had seen and even spoken to an apparition from heaven, between May and October 1917, some circumstances had made this event possible. The children grew up in very devout homes, embedded in deeply religious communities where the apparitions of Lourdes and other places were known. When neighbors heard about the apparition, the news spread quickly, provoking very different reactions from families, villages, and local priests, ranging from surprise and wonder to skepticism and rejection. However, from the second apparition in June on—they always occurred on the 13th of each month with the exception of August—a continuously growing crowd of believers had gathered at the site, first dozens, then hundreds, and finally, in September and October, thousands. There were also a number of curious skeptical visitors as well as secularist activists looking for a scandal among the crowds. Much of this resembled similar Marian apparitions in countless other places. Very soon, the children became interpreted by many in the community and in certain media outlets as authentic representatives of Portuguese rural society, as innocent, pure incarnations of local and national Catholic traditions. This belief, as we will see, was paradoxically strengthened and spread by the secularist press. Additionally, the aggressive and often very awkward attempts of free masons and a republican, anti-clerical government, and its local and regional executors to suppress the cult also had the unintended consequence of making it more popular, particularly in the northern part of the country, which has a reputation of being a stronghold of Catholicism, compared to other regions.

In mid-August 1917, the head of the local administration, a secularist republican and free mason, had the children arrested and interrogated them in his house. When they refused to admit that they lied about the apparitions, he had them put in jail and pretended that the boy, Francisco, was executed by being thrown into boiling oil. This very awkward and brutal attempt to suppress the cult, however, might have only brought forward ideas of saints being martyred and raised the stubborn resistance of the children and their supporters (

Bennett 2012a, pp. 104–5).

During the last apparition sighting on 13 October 1917, tens of thousands of pilgrims and curious people including numerous journalists arrived and many witnessed a solar spectacle—“the sun had danced”, as some said—which was seen by the believers as a sign of God while non-believers tried to understand it as a mass hallucination of an over-excited crowd standing and waiting for hours for a miracle.

A good example for how secularist activities strengthened and popularized the cult is provided by the secularist press. The leading Lisbon liberal-republican newspaper

O Século, founded in 1881 as a “voice of progress”, published a frontpage article on 15 October 1917, two days after the event (about the journal:

Barros 2015). The report was written by Avelino de Almeida (1873–1932), the correspondent of the newspaper, highlighting the importance of the apparitions, which were by far the most spectacular occurrences in Portugal that year. Almeida had worked as a journalist since he was 18 years old. In 1910, he was initiated into the Masonic Lodge of Lisbon (

Obituary 1932).

In his report of the apparitions, he emphasized how they were related to the anxieties about the military involvement of Portuguese troops on the side of the Allies on the Western front of the Great War. The famous journalist seemed to have been impressed by the masses of people that had flocked to the site. The streets were filled with cars, which added to the spectacle since that was surely a very unusual view at the time in a poor country. The article had these headlines:

“AMAZING THINGS!—The apparitions of the Virgin—What did the sign of Heaven consist of?—Many thousands of people claim that a miracle has taken place—war and peace”.

The report was based on Almeida’s own observations and interviews with people who had visited the place on the afternoon of 13 October. The famous journalist described the excitement of the three children and the business of numerous vendors. He was mostly impressed by their “coal-fire faith” that was “radicalized” by the “sign from heaven” they believed they had seen. Almeida left open how the “miracle” could be explained. He wrote:

“In the dazzled eyes of those people, whose attitude transports us to biblical times and who, pale with astonishment, with their heads uncovered, faces the blue, the sun trembled, the sun had never seen sudden movements outside of all cosmic laws—the sun ‘danced’, according to the typical expression of the peasants […] It remains for the competent to announce their judgement about the macabre ballet of the sun that today, in Fátima, made hosannas explode from the chests of the faithful and naturally left impressed—as I am assured reliable subjects—free thinkers and other people without religious concerns. who flocked to this now celebrated stretch of land.”

(O Século, 15 October 1917, frontpage. Translation by the author.)

Two weeks later, on 29 October 1917, the illustrated magazine of

O Século published a longer article with numerous photos. The secularist newspaper obviously profited financially from the enormous attention and debates the apparitions stirred, creating a media event that made the occurrence known all over Portugal and beyond.

Another way the secularist press spread the news of the apparition was by creating images which would become iconic (

Fatima 2017, p. 62). In a country where the majority of the population was illiterate, photographs had an even stronger impact. The aforementioned article was illustrated by a photograph of the three children, taken by photojournalist and photographer Joshua Benoliel (1873–1932), an image which has become iconic since then. The photo was published again on 29 October 1917 in the

Ilustração Portuguesa (supplement of

O Século no. 610). Benoliel was famous for his street scenes of Lisbon, which he had been taking since the turn of the century, showing the everyday life of the capital and its inhabitants, poor and rich (

Pavao 2018). In 1910, he was crucial in creating iconic pictures of the representatives of the new republic. (

Pinheiro 2010). How did Benoliel’s photograph of the three shepherds become an icon, one of the most reproduced images of the three “seers”?

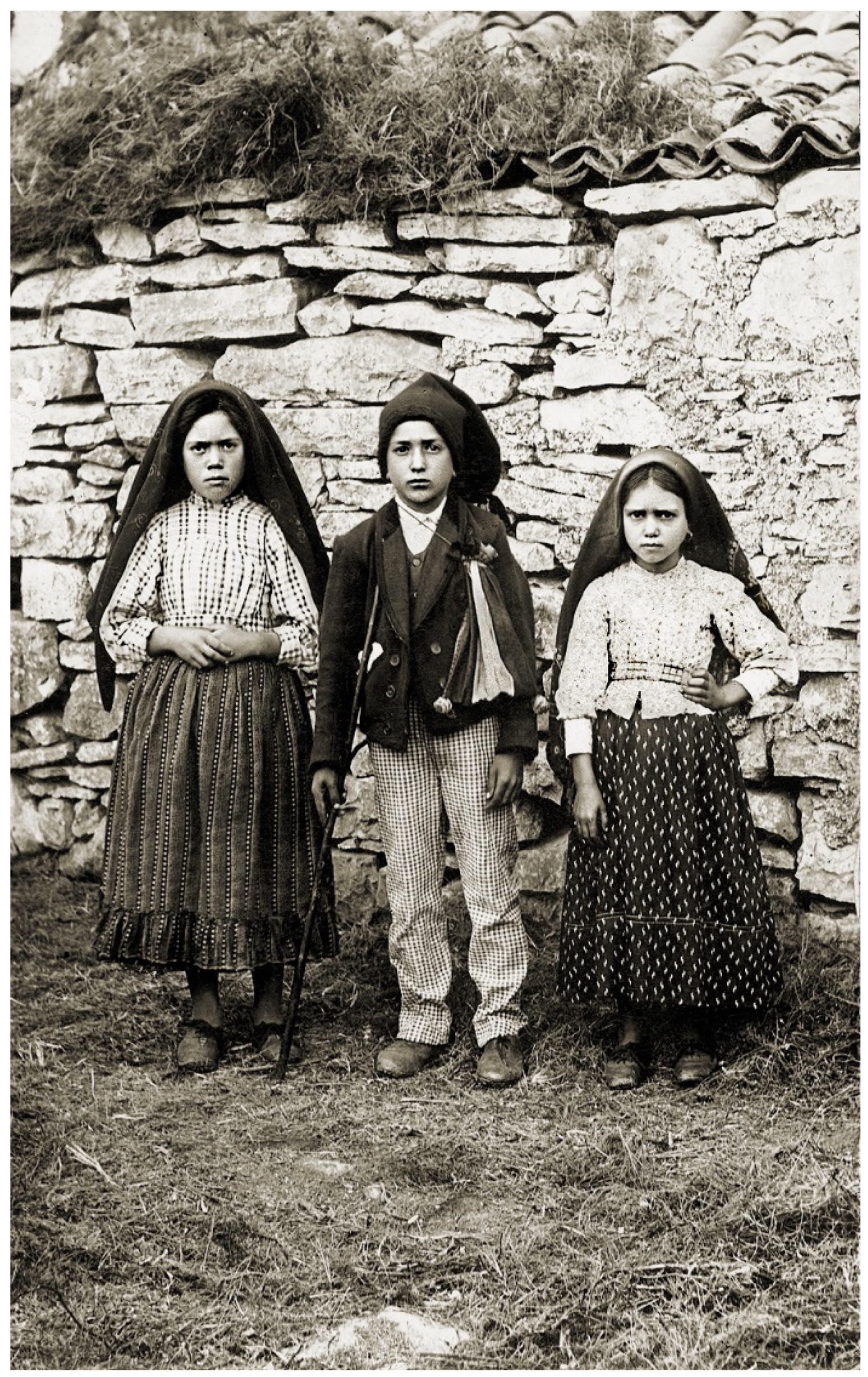

In the photo, the three children are standing next to each other on a grassy spot, in front of the wall and roof of a narrow house. The oldest and tallest, Lucia dos Santos, stands on the left, her cousin, Francisco Marto, in the center, and Francisco’s sister Jacinta, who was the youngest of the three, on the right. The children look straight at the camera, not shy, but the way they hold their hands indicates some insecurity. Lucia held her hands over her belly, Francisco has his arms hanging down, but he holds a long stick with his left hand while his right hand rests on his leg. Jancinta rests her right hand on her hip, in a more confident gesture that fits her gaze, which expresses an indomitable will to resist all hostilities, very similar to Lucia’s view. The look of their dark eyes is highlighted by their eyebrows, which are touching in the middle. The boy, however, looks more openly into the camera, although not without signs of worry.

This must have been an extremely difficult time for the three children. Thousands of people had come to see them, ask them to communicate their wishes and sorrows to the Holy Virgin, while others, including some of their parents, the authorities, as well as some anti-clerical activists, challenged and even threatened them. They were in the spotlight of these massive events (

Figure 1).

The clothes the three were wearing in the photograph give us another clue about the meaning and popularity of the picture that was obviously staged by the famous photographer. Lucia and Jacinta wore long skirts and tightly-buttoned blouses and leather shoes, which they probably only wore on Sundays and feast days. Their long black hair was covered with woolen, dark scarves. Francesco had long, light-blue and white-checkered trousers on, and he wore a dark woolen jacket over his white, buttoned-up shirt. His head was covered by a “

barrete preto da Pescador”, a long, black, woolen bobble hat, which has since become a symbol of Portuguese fishermen and peasants. These clothes marked the children as “authentical”, rural Portuguese, since anthropologists and folklore scholars had begun to define them, especially the “

barrete preto”, as symbols of Portuguese national dress during that time, in contrast to what the children of the urban upper and middle classes wore—“European” (often British) clothes, such as navy suits (

Boletim de Etnografia 1920).

In the time of a deep political, social, economic, and cultural crisis, the apparitions of the patron saint of Portugal to such emblematic representations of the nation, three innocent, authentically Portuguese children, was understood as the only sign of hope for many people. The collective reaction of many believers was so strong because it could help to relieve the private anxieties and concerns of individuals and families and helped to explain personal and collective catastrophes, such as illness, death, pandemics, world wars, political instability, and social problems, and comfort individuals, families, and the Portuguese nation. Many people had pledged, made

promessas, that they would return to Fátima if the Holy Virgin would grant them better health, or the wish that their beloved son would return safe from the war, or similar blessings (

Bennett 2012a, p. 169). The fact that Fátima at the time was difficult to reach since there was no paved road or railway line just highlights even more the resolution of so many believers to see the site.

One year after the apparitions, the Great War ended and Portuguese troops returned home. Many believers interpreted this as a fulfillment of the promises by the Holy Virgin, who was granting her grace to those who had prayed for peace and had asked for her help (Examples in:

Carvalho 2017, pp. 45–49). The war had not, as the republican leadership had hoped, united the country, or weakened the “forces of reaction”. To the contrary, it had deepened the political and social rifts within Portugal. When the new strongman, President Sidonio Pais, who was popular among Catholics—he had started to modify the law of separation between church and state—was assassinated by a left-wing radical in December 1918, political instability deepened and would continue until the establishment of the dictatorship under Salazar.

3. The Fate of the Three Children

In the context of the political and social crisis of the 1920s, the cult of Our Lady of Fátima flourished. Already in the summer of 1918, a woman had claimed that she was miraculously healed from an illness by rubbing herself with dirt from the site of the apparition, the Cova da Iria (the “hollow” of St Irene, mostly unpopulated grazing land), since there was no water. During that time, when thousands were suffering from the influenza pandemic, many had gathered in hope of being cured through miracles, which further popularized the forming cult. In 1919, a first, small chapel (“capelinha”) was built at the site of the apparition, and the influx of pilgrims in large numbers went on. In the same year, the drama around Fátima took a new turn when two of the three children died of the pandemic: Jacinta de Jesus Marto (11 March 1910–20 February 1920) and her brother Francisco de Jesus Marto (11 June 1908–4 April 1919). Francisco died when the pandemic hit the western regions strongest, during the third wave (March to September 1919), while his sister, who died in a hospital, fell victim to the fourth wave. (A study on the excess deaths per region:

Nunes et al. 2018.)

The surviving visionary, Lucia dos Santos (1907–2005), claimed that the Holy Virgin had predicted the early death of the two, by saying that they would “be soon with her” in heaven. In 2017, Pope Francis canonized them. The process of canonization had begun in 1946, which has to do with a new phase of the cult in which the Vatican became more involved, as we will see later.

The cult had begun with a massive show of strength of rural Catholic Portugal in a complex triangular conflict between the three children, local supporters and skeptics, and the Republican government and secularist activists. It was a similar reaction of a Catholic traditionalist milieu against the forces of secularism that were threatening traditional beliefs, as with the cult of Our Lady of Lourdes (1858) in the context of the revolutions of 1848/49 and the declaration of the Dogma of the Immaculate Conception of the Holy Virgin by Pope Pius IX (1854) (

Harris 2008). The knowledge of the events of Lourdes were also known to the children, at least to the oldest, Lucia, and may have inspired them (

Bennett 2012a, pp. 127, 139). The anxiety about the world war and the loss of Portuguese men on the front only heightened the sense of crisis and urgency. Bennett argues that nationalism, the idea of an exclusive, particularly strong bond between Portugal and St Mary as her patroness, was another strong motive for many followers of the cult (

Bennett 2012a, p. 198). The iconic photograph of the three children further strengthened the belief in their authenticity and innocence.

In May 1920, a first statue of “Our Lady of the Rosary”, not higher than about one meter, was procured and placed in the small chapel that was built by local cult activists. The statue was created according to descriptions provided by Lucia during interviews with one of the priests who investigated the occurrence. A year later, a bomb destroyed the chapel but not the statue, which had been temporarily moved into a private home. For the followers of the cult, this was another sign that the statue enjoyed divine protection. The seers were absent, but the cult had now an object for adoration in the form of the statue, which could be visited at the site of the apparition.

At the early stage, the Catholic Church was not yet prominent in the conflicts around the apparitions. While some priests were involved in the controversies around the apparitions of 1917, the church herself had not yet formed any clear official statement about the event and was even divided on the issue. This changed during the 1920s, when representatives of the higher clergy became increasingly the main actor in the drama, while the children had exited the stage.

Lucia, the surviving seer, was abused by her mother who did not believe her, which made her story even more plausible for others, and it also confirmed her own understanding, according to which the believers had to suffer pain if they were really to live truly to the divine message: no revelation was possible without suffering and penitence. This drama, in which not only the families and the local communities, but also various representatives of the church as well as the local and national authorities were involved, the latter mostly hostile, went on until about 1920. In 1921, Lucia left the region when she transferred to a school in Porto, about 200 km north of Fátima. In 1925, she was admitted to a convent in Spain. She only returned in 1948 to her homeland, moving into a Carmelite convent in nearby Coimbra, where she lived for the rest of her life. In 2017, Pope Francis declared Lucia a “Servant of God”. Sister Lucia, as she was called, was the main interpreter of the apparitions. She was the only one who claimed to have had communicated with the Mother of God, while the other two children had only seen but not heard her. Lucia had written down and published her memories at various times. But, most of all, she was the keeper of the famous “three secrets” that she had received from St Mary during the apparitions. These “secrets” would have an enormous impact on the cult (The following according to

Maunder 2016, pp. 33–34). The Belgian theologian Edouard Dhanis even distinguished between “Fátima I”, the 1917 apparitions themselves, which were investigated by the church, and “Fátima II”, the memories and “secrets” revealed by Sister Lucia since the 1930s, where she claimed that the Holy Virgin was concerned about the Russian Revolution and the Spread of Communism, and that she predicted the Second World War as another “punishment” by God for the lack of faith in the modern world and among Catholics (

Barreto 2003). Later, the secrets were even understood as prophecies of the unsuccessful attempt to kill Pope John Paul II, or, as other proponents think, of Pope John Paul I’s early death (one example:

https://crc-internet.org/our-doctrine/catholic-counter-reformation/murder-john-paul-i.html (accessed on 15 September 2022)). The bullet that hit Pope Wojtyła was later added to the crown of the statue of St Mary in Fátima, as a way to thank her.

4. The Portuguese Catholic Church, the Popes and the Cult since the 1920s

For the establishing of the cult, the intervention of the Catholic Church since the 1920s became crucial, as well as a stronger support from Salazar’s Estado Novo (1933–1974), which was based on Catholic nationalism, in the following decades.

Since 1920, one of the main protagonists of the cult became the new bishop of Leiria, Dom Jose Alves Correia da Silva (1872–1957). Before being appointed, Bishop Da Silva had been persecuted, incarcerated and exiled by the Republican regime. On his first visit to the site, which was part of his diocese, in September 1921, he bought the land around it with the intention to build a basilica and a hospital to commemorate the apparition. Miraculous healings went on, now by applying water from a well Bishop da Silva had ordered to be dug out at the site, so the practice of using dirt for healing could be replaced by one that was closer to the model of Lourdes where the water from the well in the grotto had a central symbolic meaning of healing through cleansing.

In 1922, Bishop Da Silva improved the publicity of the cult, and at the same time also strengthened the control by the church, by inaugurating the newspaper

Voz da Fátima (the

Voz da Fátima or “

Voice of Fatima” is still published today, celebrating, in 2022, its hundredth anniversary. See:

https://www.fatima.pt/pt/pages/voz-da-fatima (accessed on 15 September 2022)). The paper would appear every month, on the 13th, highlighting the days of the apparitions, providing an official, church-sanctioned narrative of the events and everything related to them, starting with an article about the 5th anniversary (“5 anos depois”, in:

https://www.fatima.pt/pt/documentacao/vf0002-voz-da-fatima-1922-11-13 (accessed on 15 September 2022)). It reported on any celebration at the site or about the fate of the three children but also included articles about the history of the apparitions at Lourdes, as well as articles about Marian liturgy and similar topics, for example, about Padre Pio, an Italian monk famous for his hand stigmata (On Padre Pio’s complex relationship with Italian Fascism, cfr.

Luzzatto 2007). Bishop Da Silva often published announcements or reflections in the

Voz.

With the second number (November 1922), Voz da Fátima started a series under the headline “Las curas de Fátima”, with monthly articles that documented medical cases, photos of the patients, doctor’s certificates, and other information on people who claimed they were cured with the help of Our Lady of Fátima (see, for example. Voz de Fátima, 13 January 1923. VF0080_1923-01-13.pdf). Other official publications followed, which also required church approval. On the site, the construction of the basilica and of the surrounding monumental colonnades began in 1928 and was finalized in 1954. Most importantly, Bishop Da Silva ordered an official investigation of the events of 1917, which was terminated in 1930 with a positive result, confirming that a miracle had happened at the site. Now, numerous chapels dedicated to Our Lady of Fátima were built all over the country. A good example is the church Nossa Senhora de Fátima in Lisbon. Planned since 1930, construction began in 1933 and the inauguration followed in 1938.

On 13 October 1935, 18 years after the last apparition and the “miracle of the sun”, Voz da Fátima (now with more than 300,000 copies sold) reported about the reburial of Jacinta Marto. The youngest of the three seers had initially been buried in Ourem, the neighboring city, in 1920. Now, her corpse was exhumed and was found, like a saint’s body, “perfectly uncorrupted” when the cask was opened. Then, it was brought in a procession to Fátima, where the remains were reburied in the local cemetery. From now on, it was more convenient for pilgrims to visit both the capelinha and Jacinta’s gravesite nearby. In 1951, she and her brother Francisco were both laid to rest inside the basilica, raising the religious significance of the building.

Since 1926, the political context had also changed dramatically while the cult was already established as a popular pilgrimage. At the tenth anniversary of the apparitions, tens of thousands had come to the site and prayed in front of the small chapel and the statue, and priests gave out communions to the masses of believers (

Fatima 2017, p. 94).

After the fall of the secularist republic and of various right-wing coups, the economics professor and Catholic politician Antonio Oliveira da Salazar proclaimed the

Estado Novo, a new authoritarian regime. Although Salazar’s relationship with the Catholic Church was not free of complications—he insisted on the church keeping out of politics and “in public he held aloof of the cult of Fátima”—the atmosphere for Catholic activities were now more advantageous compared to the previous regime that had tried to introduce French-style laicism in a Catholic stronghold (

Gallagher 2020, p. 65). Salazar, who proclaimed that he would restore the Portuguese nation, described the meaning of Catholicism as such:

“Portugal was born in the shadow of the Catholic Church and religion, from the beginning it was the formative element of the soul of the nation, and the dominant it of character of the Portuguese people.”.

The Portuguese bishops conference had decided, in a meeting in 1926, that it had to work on the “religious restauration of the fatherland” and the overcoming of the problems created by “the irreligiosity of the upper classes and the dechristianization of the popular masses” during the First Republic (Quoted by

Dix 2008, p. 167). Like in other countries, this task was mostly taken on by the mass organizations of Catholic Action (

Acção Católica Portuguesa), an apolitical movement strictly controlled by local bishops and strongly supported by Pope Pius XI (1922–1939). (For Germany, France and Italy, see:

Große-Kracht 2016; For Portugal:

Brandão 2018.)

One result of this mobilization and organization of Catholic masses was a period of boom for Catholic groups and a growing number of priests, which ended only in the 1960s. Politically, Catholics had already started to organize in 1917, when a “

Centro Católico Portugues” was founded, in which both Salazar and Cerejeira, later archbishop of Lisbon, were active (

Brandão 2004, p. 48).

Very soon, strong support for the cult of Fátima came increasingly also from the Vatican in an attempt to gain more control over the growing popular movement. In 1929, Pope Pius XI blessed a statue of the Virgin of Fátima, which was created for the new chapel of the Portuguese College in Rome. By that time, however, the Vatican still treated Fátima mostly as a Portuguese national symbol. When Pius XII consecrated the world to the Immaculate Heart of St Mary in 1942 (31 October), he sent a message in Portuguese via Radio Vatican, also in strong support of Salazar’s regime, which stayed neutral during the war. In 1946, a Vatican legate, sent by Pius XII, arrived at Fátima and crowned the statue, raising its importance as a sacred object and demonstrating the full official support of Rome. In the same year, a “pilgrimage statue” of Our Lady of Fátima was blessed, which was supposed to bring the message to different parts of the world.

During the Cold War, Papal support for the cult further increased. Eventually, however, the message changed: from anti-communism to peace. In 1956, Cardinal Roncalli, two years before he was elected as Pope John XXIII, visited the sanctuary in Fátima at the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the pilgrimage of the statue of Our Lady. (The following according to:

https://www.newsmuseum.pt/pt/Fátima/Fátima-altar-do-mundo (accessed on 15 September 2022)) Eleven years later, at the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the apparitions, Pope Paul VI celebrated mass in Fátima, as the first pope to visit the shrine in person. It was also one of the rare occasions when Sister Lucia returned to the site.

During his visit, against the background of the II Vatican Council and the period of East-West Détente, Pope Paul VI toned town the earlier anti-communist rhetoric of Pius XII, emphasizing instead a slightly different message, calling the Virgin “Our Lady of Peace”. By the mid-1960s, the visitors to the shrine counted already more than one million per year, and they also included celebrities such as Sofia Loren and her husband, Carlo Ponti. This coincided with the beginning of Portugal’s slow opening to mass tourism. While the country hosted about 220,000 visitors in 1955–1956, the number rose to 1.2 million in 1969–1970 (Cfr.

Garcia 2014, Table 6).

When the Salazar Regime fell during the Carnation Revolution of 1974, the rather de-politicized message of peace helped to keep the shrine and the cult of Our Lady of Fátima out of the political conflicts of the time, although it might also have strengthened the resistance against attempts to turn Portugal into a communist or Marxist regime, attempts which failed in the years immediately following the revolution. John Paul II, elected as pope in 1978, raised the anti-communist undertones of Catholicism again, however, in a modified way. More important for his engagement with Fátima was a personal incident. For the Polish pope, the prophecy of the “Third Secret”, in which the seer was told by St Mary that a pope would be assassinated, had gained a personal significance. He was shot on St Peter’s Square on the 13 May 1981, exactly on the 64th anniversary of the first Fátima apparition. After his recovery, the Pope visited Portugal to thank Our Lady of Fátima for his miraculous rescue.

The visit of the second pope occurred three decades after the dedication of the first basilica (1954). Since then, numerous new chapels, statues, and buildings (a new basilica in 2007) have been added to the complex. The bucolic field where sheep grazed in 1917 has become a town with hundreds of pilgrimage hotels and spas, souvenir shops, and many other tourist attractions to accommodate and entertain millions of visitors each year (

Lopes 2020). The climax, for now, was reached in 2017, when Pope Francis visited Fátima at the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the apparitions, and almost ten million pilgrims were counted. While the Bishop of Leiria had taken control of the cult in the 1920s, after 1945 it was the Vatican which had continuously increased the significance of the cult of Our Lady of Fátima, adding a transnational level to its still existing local, regional, and national meanings.

5. The Vatican, Portuguese Colonialism, and Our Lady of Fátima

During the first two decades, between 1917 and the mid-1930s, the cult had become very important for the local, regional, and national self-understanding of many Portuguese Catholics. Already in 1923, the Voz da Fátima triumphantly reported about a “national pilgrimage” movement in all provinces of the country on 13 May, initiated by and related to the apparitions of 1917 (“A pereginação nacional”, Voz da Fátima, 13 June 1923.). In June 1926, the front page of the paper announced “A Grande Peregrinação Nacional De Maio” with Fátima being the “magnetic pole of souls”. The strong support from the local bishop and from Catholic politicians and its unrelenting popularity had strengthened its national significance.

Soon, the cult would also gain increased significance for the Portuguese colonies and the Portuguese diaspora all over the world. After the cult had reached the Portuguese college of Rome in 1929, Catholic missionaries brought the cult to colonies in Africa, considered to be part of the “Ultramar” Empire. Already two years earlier, in 1927, a first “Mission of Our Lady of Fátima” was inaugurated by Spiritan Fathers in Ganda, Angola, supported by the Portuguese government, in defense of activities of “de-nationalization” in the form of two Protestant missions from Switzerland and the USA (“Missão de N. Senhora de Fátima em Africa”, Voz da Fátima, 13 October 1930). The mission in Ndunde (Ganda) is still functioning today (Missao–Portal da Ganda (siteganda.azurewebsites.net)). The Spiritans or “Fathers of the Congregation of the Holy Spirit”, which was founded in France in 1703, were very active in French colonies, mostly in Africa (Cfr. CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Religious Congregations of the Holy Ghost (newadvent.org).

In 1929, a church dedicated to Our Lady of Fátima opened in Macao (Macau), the Portuguese colony in China. Until today, a procession of a statue of the Virgin has also been carried around during a feast day (

Couto 2014). In 1936, the

Voz da Fátima reported about a “mission of Our Lady of Fátima” in the province of Moxico, Angola. The Catholic Church, which today represents a bit less than half of the population, had already been present in Angola since the first Portuguese colonies in the late 15th century (

https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/angola-catholic-church (accessed on 15 September 2022)). During the Republic, from 1910 to 1933, some Catholic missions in Angola were suppressed, then reinstalled by the

Estado Novo.

In 1933, a school, also dedicated to Our Lady of Fátima, was opened in Mozambique by the Benedictine Mission of Muchopes in the town of Mazucane (“Em Moçambique–Inauguração da nova escola de Nossa Senhora de Fátima, de Mazucane, sucursal da Missão de S. Benedito dos Muchopes”, Voz da Fátima 15 (170) 13 November 1936, p. 3). However, these were still singular, local initiatives.

While the concordat demonstrated that Salazar was not willing to give the church more influence on areas over which the republic had gained control since the 19th century—civil marriage, civil divorce, appointment of bishops (nominated by the Vatican but with final approval from the government), and religious education in schools (remained voluntary)—the role of the church in general and symbolically (presence during state ceremonies, for example), but mostly in the colonies, was strengthened. Brandão interprets this as the beginning of a new phase in the relationship between the Portuguese church and state under Salazar, from “separation” (1910–1933) to “collaboration” (1933-mid-1960s) (

Brandão 2004, p. 44).

While the Vatican fully supported the Estado Novo and Portuguese colonialism, the Portuguese government gave full liberty of action to Catholic organizations and institutions in the colonies, a development which found its climax in the signing of the

Acordo Missionario of 1940 (

Da Cruz 1997;

Brandão 2004, p. 57).

Pope Pius XII had praised the Portuguese colonial empire and its achievements in the aforementioned Encyclical

Saeculo Exeunte Octavo. Here, the pope wrote:

“And indeed, the Catholic faith, which nourished the nation of Portugal from its very origin, was the principal force which raised your fatherland to the peak of its glory, extending the boundaries of both religion and empire. The Church adorned Portugal with all the embellishments of culture and rendered it worthy of its sacred endeavors in missions. […] And now, when more than a few European nations have been lost to the Church because of the changes in these calamitous times, We see your people and their Spanish brothers opening paths and laboring for the Church in the spacious lands of Africa, Asia, and America. There they recruit numerous adherents of the Church to replace those who have miserably left her embrace. Then dioceses, parishes, sacred seminaries, monasteries, hospitals, and public orphanages arise almost everywhere in these places to prove the vital force and perennial virtue of the Catholic Church.”

With papal support, from the 1940s to the 1950s, the cult spread further in the Portuguese colonial empire, where it was supposed to emphasize the Portuguese national character of the “Ultramar”, the imagined community of all areas controlled by the country in Europe, Africa, and Asia.

This trend can be exemplified by the sanctuary of

Nossa Senhora de Fátima in Namaacha, Province of Maputo, in Mozambique, that was built at the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the apparitions in 1942 (A dissertation of the pilgrimage to Namaacha was published in 2016 at the Escola Superior de Hotelaria e Turismo do Estoril:

Neves 2016). The building was inaugurated two years later under the leadership of Cardinal Cerejeira, the Patriarch of Lisbon. The architectural style emphasized the Portuguese national character of the church (photo:

https://www.indico-lam.com/2021/04/22/santuario-de-nossa-senhora-de-Fátima/ (accessed on 15 September 2022)). Built in “estilo manuelino”, a late Gothic, early Renaissance Portuguese style going back to the 16th century but applied until the 19th century, the building was supposed to represent a continuity of Colonial Portugal from the beginning of overseas expansion to the 20th century as well as the identity between “motherland” and colony, the very idea of the “Ultramar”. Buildings of this style can be found in all parts of the former empire: from mainland Portugal to the Azores, to Cape Verde, Angola and Mozambique, to India (Goa), and even at the coast of Iran (Strait of Hormuz) (See the list:

https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Estilo_manuelino#Obras_principais (accessed on 15 September 2022)). The Portuguese style of the buildings was an expression of the “ultramarine” ideology, which claimed that Portugal and all its overseas colonies in Africa or Asia were all parts of “one and indivisible Portugal” (

Brandão 2019, p. 222).

As mentioned before, a new statue of Our Lady of Fátima was created in 1946, and various copies were produced to further spread the cult. The artist of the second statue of 1946 was the sculptor José Ferreira Thedim (1892–1971), who came from a village in the North. Sister Lucia liked this second statute better than the first because she found it looked more like the holy woman she had seen in the sky. She also recommended to Bishop Da Silva that this second statue should be the “pilgrim statue”. Pope Pius XII gave his special support to this second statue, crowning her and giving her the name of “International Pilgrim Virgin Statue of Our Lady of Fátima” (how the statues were later translated into a tool to promote tourism has been studied by:

Heitor 2019).

In the summer of 1948, the statue left the harbor of Lisbon on a ship that brought it to Africa, mostly, but not exclusively, to Portuguese colonies, from the islands of São Tomé e Príncipe to Angola, then to Mozambique, from there to various South and East African colonies, and, finally, to Cairo. In many of these places, the visits of the statue inspired the buildings of churches and sanctuaries dedicated to Our Lady of Fátima in the following decades. When the statue arrived in Benguela (Angola) in July 1948, the Governor of the province, Mario da Costa Ribeiro Zanatti (1898–1970), and the priest, Dom Manuel Junqueira, pledged to build a church for the Holy Virgin. It took another 20 years until the cathedral was opened (

https://www.verangola.net/va/pt/012020/sugestoes/17799/Catedral-de-Benguela-O-que-fazer.htm (accessed on 15 September 2022)). Before he arrived in Angola, Zanatti, formerly a Navy officer, was acting governor of Portuguese Guinea (Bissao) (

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/List_of_governors_of_Portuguese_Guinea (accessed on 15 September 2022)).

It needs to be further studied how the Portuguese diaspora in the colonies, and, most of all, the colonized peoples, reacted to the “implantation” of the cult of Fátima. What we know so far indicates that it was the colonial elites, officers, priests, and missionaries who brought the cult in the form of dedications of churches, chapels, or schools. Later, images and statues were also added. But the sanctuary of Namaacha, built by order of colonial elites, is also a good example of a colonial foundation that was fully embraced and taken over by the local, formerly colonized population. Until today, every year, thousands of Mozambiquans celebrate with a procession of the statue of Our Lady of Fátima. (A photo of the 2019 procession can be found here:

https://clubofmozambique.com/news/this-saturday-more-than-15000-catholics-to-make-the-pilgrimage-to-namaacha/ (accessed on 15 September 2022). There is a short video that shows the procession on 13 October 2017 in Namaacha:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aqHA9rc6CYA (accessed on 15 September 2022)). In the end, the Portuguese character of the church building could not prevent the cult from being transplanted into other, non-Portuguese cultures. This had to do with the Vatican’s tendency to nominate indigenous African priests and bishops, increasingly after 1945.

This practice was already indicated in

Saeculo Exeunte, in which Pope Pius XII prayed “that God may inspire both the people of Portugal and those of the nations subject to your rule to become priests or coadjutor brothers or nuns or catechists devoted to missionary work. […] Those who have been called to the sacred orders of the contemplative life are to pray for this special intention, and the faithful, when reciting the rosary so highly commended by the Blessed Virgin at Fátima, should entreat this same Virgin to intercede in favor of this divine vocation in order that the missions will flourish” (

https://www.vatican.va/content/pius-xii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xii_enc_13061940_saeculo-exeunte-octavo.html (accessed on 15 September 2022)).

However, increasingly after the Second Vatican Council, the Africanization of the Catholic clergy in Mozambique led to growing tensions with the Portuguese colonial regime (

Brandão 2004,

2019). The wish of the government of the Estado Novo to prefer missionaries from Portugal and the “nationalization of missionary activity” in the colonies had become, according to Pedro Ramos Brandão, “a constant source of friction with the Catholic Church” (

Brandão 2019, p. 223). The trend of transnationalization of the cult of Our Lady of Fátima can also be observed when we look at the close connection between the cult and the history of Portuguese emigration.

6. Migration and the Transnationalization of the Cult

The history of Portuguese emigration stretches back to the 15th century and intensified from the mid-19th century when a conspicuous part of the Portuguese population (more than 10%) left the country for Brazil or North America. During the 20th century, mostly after 1950, more than one million Portuguese moved to France, West Germany, Switzerland, but also to the United States and Australia. Encouraged by the government but less popular, attracting only several thousand people, was the movement to the colonies in Africa, which Portugal lost after a long war (1961–1974).

Only from around 1980 did the trend turn, and significant immigration to Portugal set in, mostly from the former colonies (including Brazil), which mixed both white “settlers” or returning emigrants and people of African descent (an overview provides:

Kalter 2022). While emigration from Portugal to North Western Europe continued, migrants from the lusophone (Portuguese-speaking) world flocked to the country.

In this context, the cult of Our Lady of Fátima also began to migrate, a phenomenon David Morgan has called the “inversion of the pilgrimage” since this cult did not only attract them but also moved to the pilgrims (

Morgan 2009, p. 52. See also:

https://observador.pt/especiais/a-historia-e-o-impacto-de-Fátima-o-milagre-dos-crentes/ (accessed on 15 September 2022)). This movement must also be distinguished from the procession of the statue on particular feast days, such as on the 13th of May, June, July, August, September, and October, when the statue still stays in the vicinity of the site. After World War II, the cult of the statue spread rapidly in the United States and Latin America. A good example for this was the large copy of the statue of Our Lady of Fátima that was erected in Petropolis, Brazil, in 1947. Already in 1931, the

Voz da Fátima reported about an article on Fátima in the Vozes de Petropolis” (Cfr. “Fátima no Brasil”,

Voz da Fátima, 13 December 1931.

https://www.fatima.pt/files/upload/voz_da_fatima/VF0111_1931-12-13.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2022)). The “throne” with the 14 m high statue was planned by the engineer Heitor da Silva Costa, who had also built the Christ Redeemer monument on Corcovado mountain in Rio de Janeiro, the iconic symbol of Brazil. (A photo of the statue:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/shinagawa/14263026591 (accessed on 15 September 2022). About the architect:

Giumbelli 2008.) The building was initiated by the Franciscan Friar José Pereira de Castro (1896–1962), who was cured from an illness and wanted to express his gratitude to Our Lady of Fátima. (

https://www.tripadvisor.com.br/Attraction_Review-g303504-d556680-Reviews-Trono_de_Fátima-Petropolis_State_of_Rio_de_Janeiro.html (accessed on 15 September 2022). The short biography of Franciscans does not mention Frei Pdreira’s involvement in the building of the throne.

https://franciscanos.org.br/quemsomos/personagens/frei-joao-jose-pedreira-de-castro/#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 15 September 2022)).

It needs to be further investigated why the friar and the Catholics involved in the erection of this monumental statue chose the Portuguese version of St Mary. The Cult of Fátima had been known in Brazil at least since the early 1930s. And why Petropolis? Did it have to do with its character as the “imperial city” where the cult of the Brazilian monarchy was (is?) centered, and where the population was mostly of German and Portuguese, white origin?

The anti-communist message, which Sister Lucia had revealed as the “second secret” she had received from Our Lady of Fátima in 1941, surely contributed to the spread of the cult among certain groups and institutions beyond the lusophone sphere. Lucia revealed these words of the Holy Virgin as the “second secret” in a letter to the Bishop of Leiria in 1941: “When you see a night illumined by an unknown light, know that this is the great sign given you by God that he is about to punish the world for its crimes, by means of war, famine, and persecutions of the Church and of the Holy Father. To prevent this, I shall come to ask for the consecration of Russia to my Immaculate Heart, and the Communion of reparation on the First Saturdays. If my requests are heeded, Russia will be converted, and there will be peace; if not, she will spread her errors throughout the world, causing wars and persecutions of the Church. The good will be martyred; the Holy Father will have much to suffer; various nations will be annihilated. In the end, my Immaculate Heart will triumph. The Holy Father will consecrate Russia to me, and she shall be converted, and a period of peace will be granted to the world.” (Cit. in:

https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_20000626_message-Fátima_en.html (accessed on 15 September 2022)).

The aforementioned “Blue Army of Our Lady of Fátima”, founded in the USA, erected a building on the Fátima site that would later become the “Domus Pacis”. In 1963, a Catholic-Byzantine (Catholic church of Eastern Rite) Chapel was opened there, which would late become a place of numerous, mostly Ukrainian pilgrims to Fátima but also a place where Ukrainian immigrants to Portugal, a growing group since the 1990s, would gather (

Vilaça 2008).

Those initiatives that charged the cult with anti-communist messages tended to undermine attempts of the Portuguese colonial elites to create symbolic “Portuguese spaces” in the colonies because they emphasized a universal message. In 1948, a year before one of the traveling pilgrimage statues was shipped to the African continent, another pilgrimage statue was brought to Canada and the United States, accompanied by the founder of the “Our Lady’s Blue Army”, John Haffert (story in:

https://www.corpuschristiphx.org/statue (accessed on 15 September 2022)). Hundreds of thousands of Catholics (and maybe others who were curious) attended the processions of the statue in Buffalo/NY, St Louis, Chicago, and other places.

Before the voyage, the Bishop of Leiria had blessed the traveling statue in Fátima on 13 October 1947. The idea of the traveling statues was to bring the blessings of Our Lady of Fátima to all parts of the world to those who could not travel to Fátima. In 1951, the statue returned to Rome, where the Holy Father announced in a radio message:

“In 1946, I crowned Our Lady of Fátima as Queen of the World and the following year, through the Pilgrim Virgin, She set forth as though to claim Her dominion, and the favors She performs along the way are such that we can hardly believe what we are seeing with our eyes.”

During that time, the cult also spread to British and French colonies in Africa, further relativizing its Portuguese character. In the summer of 1949, a statue of Our Lady of Fátima was brought, by Belgian missionaries of the order of Oblates of Mary Immaculate, from their mission in Roma (since 1862) to Basutoland (today: Lesotho), a British colony at the time (described in

Maria 1958, pp. 186–87; about the mission:

https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02346a.htm (accessed on 15 September 2022)). In 1951, the pilgrimage statue was shown in Australia, where it was also mainly understood as a symbol of anti-communism (

Mason 2008).

7. Beyond Anti-Communism: A Cult of the Lusophone World

In most places, the cult today still marks the existence of a significant Portuguese diaspora. One such country is Luxembourg, where today a fifth to a quarter of the population has Portuguese roots. Since 1968, on Assumption Day, a procession is held in the church “Notre Dame de Fátima”, in the small industrial town of Wiltz (Wooltz). With a population of about 7000, of which half are foreigners, the c 1600 Portuguese are the largest group (20%). Additionally, there are also 108 Capeverdians, 30 Brazilians, and 22 Guineans, which contribute to the lusophone community. The procession of Our Lady of Fátima in Wiltz is the best example of the connection between Portuguese (and lusophone) emigration and the strong national symbol of Fátima, since the procession here was started by emigres. (Statistics:

https://www.wiltz.lu/fr/la-commune/informations-generales/chiffres-et-statistiques. A photo of the procession:

https://luxembourg.public.lu/fr/societe-et-culture/fetes-et-traditions/notre-dame-de-Fátima.html (accessed on 15 September 2022)).

Another example is Notre-Dame-de-Fátima, or “Marie Mediatrice” in the 19th Arrondissement of Paris, which was built in 1954 but only later became the church of the large Portuguese diaspora in the French capital (

https://cityseeker.com/paris/361400-sanctuaire-notre-dame-de-Fátima, see also:

https://www.sanctuaireFátima.fr/ (accessed on 15 September 2022)). In 1944, Cardinal Suhard had promised to erect a church to thank St Mary if the Germans would not destroy Paris. When the church was inaugurated, it was dedicated to

Mary Mediatrix of All Graces. The church was closed in 1974 because it had no parish. It reopened in 1988 by Cardinal Lustiger, and was given to the Portuguese community of Paris, again as a marker of Portuguese national identity of a diaspora.

In many places, the cult of Our Lady of Fátima mixed with other Marian cults. In 2013, the parish of St James in Newark, NJ organized a procession of both the statue of Fátima and the statue of Our Lady of Aparecida, which is related to an 18th century Brazilian cult (a description of the procession can be found in the bulletin of St James Parish:

https://container.parishesonline.com/bulletins/04/1092/20131013B.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2022)). The Brazilian cult goes back to the tradition according to which fishermen in Aparecida (Sao Paolo) found a clay statue of St Mary in 1717. The parish priest, Fr Clement Krug, a Redemptorist, explained in the parish bulletin that the adoration of the Holy Virgin was crucial for the Italian founder of his order, Alfonso Liguori. He hoped that the procession would bring together the traditions of Brazilians and Portuguese believers and create a lusophone community, an attempt he had started in 2001, quoting a statement from the US Catholic Bishops Conference about immigrants “Welcoming the Strangers Among Us: Unity in Diversity” (2000). The procession and the parish festival that followed were supposed to ease tensions between the Portuguese and the Brazilian communities and within the Brazilian groups of Newark, but intra-religious tensions and cultural differences (for example, the use of music in the liturgy), for example, between pro-Liberation Theology groups and charismatic groups, could not fully be bridged (

Gidal 2016, p. 212). Another Portuguese church in Newark, Our Lady of Fátima (

Igreja Nossa Senhora de Fátima), has been involved in the festivities of the more Brazilian parish of St James.

This example demonstrates how the cult was sometimes successfully used to emphasize Portuguese identity in places of diaspora but how such attempts were undermined in other places where the cult had rather universal meanings, such as “anti-communism” or “peace”, or where it became a symbol of a mixed lusophone community. Voz da Fátima had already started to report at least since 1933 about “O culto de N. S.de Fátima na estranjeiro” (the cult of Our Lady of Fátima abroad) (Voz da Fátima, 13 August 1933, p. 2.). In these reports, it was often Portuguese living abroad who propagated the cult within the local Catholic communities, but, in many cases, it was others who had heard of the apparitions and became followers. For the officials who wrote for the Voz da Fátima, some of them priests, the spread of the cult beyond the Portuguese-speaking world was an important sign of its significance, maybe even a confirmation of its legitimacy. The more people who venerated Our Lady of Fátima, the more important the cult became, and the more difficult it became to deny its truth.

Since the 1990s, and the dissolution of the “parish civilization” that had dominated Portuguese Catholicism for a long time, the cult has become a place for those who are “believing without belonging”, to quote a concept developed by Danièle Hervieu-Léger (

Hervieu-Léger 2010, pp. 91–92). Coutinho, Teixeira, and others have applied this concept for the changes in Portuguese religiosity (

Coutinho 2020, p. 60;

Teixeira et al. 2019). The dissolution of the Portuguese “parish civilization” since the 1960s was caused by emigration and the abandonment of rural areas, urbanization, the dramatic political, social, and cultural changes in the aftermath of the 1974 revolution as well as Portugal’s entry into the European Economic Community (1986), which contributed to a rise in (secular) education and higher incomes. Since then, processes of individualization and shifts in values have further undermined religious practices and strong commitments to Catholic institutions in the urban centers of the country, which became not only less Catholic but also religiously more pluralistic and more secular. The resulting individualization of religion could be understood as the transformation of the believer from a “parishioner” to a “pilgrim” (

Coutinho 2020, p. 61). This transformation could explain, together with the boom of tourism and a much better infrastructure—Fátima has been connected to a highway that runs from Porto in the north to Lisbon in the south—why the pilgrimage site of Fátima has been attracting more visitors in a time of increasing erosion of traditional Catholicism. The French sociologist Daniele Hervieu-Léger describes the underlying paradox thus: for him, the “subjectivization of beliefs”, a result of the dissolution of the “parish civilization”, is paralleled by the growth of “new forms of religious sociability” with mass events such as the Catholic Youth Day or pilgrimages (

Hervieu-Léger 2010, pp. 91–92).

Finally, immigration to Portugal also had a significant impact on the cult of Fátima. Since the 1990s, Portugal, which still experienced significant emigration, especially to France, Germany, Switzerland, but also to Brazil, has become a country in which immigration has surpassed emigration. In 2020, about 10% of the population of about 10 million were immigrants (

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/images/7/79/Tab01_Immigration_by_citizenship%2C_2020.png (accessed on 15 September 2022)). Of these one million people, more than 24,000 were Portuguese citizens who were born outside the country. Based on the citizenship laws of Portugal, children and grandchildren of former Portuguese citizens can claim citizenship, which has the effect that hundreds of thousands of Brazilians, for example, can claim Portuguese citizenship, which gives them a legal way to emigrate to Portugal. However, there are also 183,000 Brazilian citizens in Portugal, the largest group of foreigners, followed by 36,000 Cape Verdeans, 24,000 Angolans, almost 20,000 from Guinea Bissao and 10,000 from St Tome and Principe, while there were also 30,000 Romanians, 29,000 Ukrainians (before the War of 2022!), 17,000 Spaniards, and 46,000 Britons (

https://sefstat.sef.pt/Docs/Rifa2020.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2022)). Another large group consists of Indians (about 24,000). These groups all have very different legal statuses and live under various social and economic conditions. How did the growing immigration shape the cult of Our Lady of Fátima?

In 1962, the archbishop of Lisbon founded the

Obra Católica Portuguesa de Migrações (Portuguese Office of Migrations) as part of the Caritas. The founding of this particular office was inspired by new ideas about migration, formulated during the Second Vatican Council (

https://sites.ecclesia.pt/ocpm/a-servir-os-migrantes-ha-4-decadas/ (accessed on 15 September 2022)). In 1978, the office became part of the Bishops Commission of Migration and Tourism (

Comissão Episcopal de Migrações e Turismo) of the Portuguese Bishop’s conference. In the beginning, the office was mostly concerned with study, pastoral work, and support of Portuguese emigrants; later, another focus became increasing support for immigrants arriving in the country. At the same time, the office still supports priests who serve the Portuguese diaspora as part of the Catholic Missions of Portuguese Language (

Missões Católicas de Língua Portuguesa). The office tries to coordinate religious and social activities of the church towards members of the Romani people, sailors, refugees, foreign students in Portugal, domestic workers, tourists, and pilgrims, quite a list of different target groups.

Since 1973, the office organized “Migration Weeks” and a pilgrimage to Fátima (

Semana Nacional das Migrações 1973). In 2021, on the 13th of August, Cardinal Jean-Claude Höllerich, Archbishop of Luxembourg, led the pilgrimage, which was a gesture towards more than 90,000 people of Portuguese background in Luxembourg. At the same time, the pilgrimage was also meant to include immigrants and refugees from other countries, in relation to Pope Francis’ appeal to support refugees as one of the priorities of church support (

https://www.vaticannews.va/pt/igreja/news/2021-07/portugal-semana-nacional-migracoes-peregrinacao-Fátima.html (accessed on 15 September 2022)). In 2018, of the 321 groups who signed up for the annual Pilgrimage of migration and refuges, 85 were Portuguese and 236 came from abroad.

While Fátima is becoming, in accordance with the Catholic Church and the Vatican, a symbol of integration of immigrants, the site is also turning into a religious space open to numerous groups of non-Catholics and even non-Christians. This is a trend which has also been observed for other pilgrimage sites, including Santiago de Compostela and even the Vatican, for quite some time (

Nolan and Nolan 1992). As already mentioned, followers of the Catholic-Byzantine or Orthodox rite, mostly from Ukraine, had arrived as pilgrims in Fátima since the chapel with an icon of Our Lady of Kazan was opened in 1963. But more numerous groups from Eastern Europe, including immigrants, would celebrate their place of origin in Fátima after the fall of communism (

Vilaça 2008). Later, also a Greek-Orthodox Ukrainian church started to use the Byzantine Chapel in Fátima to support pilgrims.

More recently, the presence of Muslim pilgrims in Fátima occurred. One case in particular was the young Lebanese who arrived in 2017 from Spain, where he was on a holiday and where he had heard about the pilgrimage site. To the astonishment of many, he promised he would move the last part of the pilgrimage on his knees, which he did with support from other pilgrims (

https://www.dn.pt/sociedade/hjhj-8107506.html (accessed on 15 September 2022)). There has been an influx from Muslim pilgrims, which is in part explained by the importance of the name of Fátima, which is also the name of the daughter of the prophet Mohamed. According to a legend, the place is named after a Muslim princess who had converted to Christianity because of her love for a Christian knight.

More attention in religious studies has been paid, however, to a group of Hindu immigrants to Portugal. Fátima has been visited by Hindu pilgrims at least since 1954, but their number rose significantly after 1975 when many Gujaratis left Mozambique (

https://www.publico.pt/2004/09/30/sociedade/noticia/hindus-vao-a-Fátima-ha-50-anos-1204769 (accessed on 15 September 2022)). Other Indian Hindus had left Goa after the Indian invasion and had settled also in Mozambique (

Brandão 2004, p. 62). This diaspora also has close ties with Mozambique, the United Kingdom, and India. In Portugal, they mostly live in Lisbon, where a number of different Hindu temples can be found.

The anthropologists Rita Cachado and Ines Lourenço have done extensive studies of this phenomenon (

Lourenço and Cachado 2022;

Cachado and Lourenço 2020). The Gujarati Hindu diaspora is the largest among South Asians in Portugal, counting about 30,000. Some of the groups related to Gujarati Hinduism have incorporated elements of the Catholic cult of Mary, especially in the form of Our Lady of Fátima, resulting in a hybridization of the cult of Our Lady of Fátima with Hindu religious practices. Here, Our Lady of Fátima has been transformed into a Hindu goddess and is being worshipped along more traditional Indian goddesses in daily prayer practices and in the form of figures included in shrines in temples and at home. This has not only been observed in Portugal, but also in Mozambique, Great Britain, and India among the Gujarati Hindus. The statues are often bought during trips to Fátima, and then taken to other places. Families also buy other religious objects, such as holy water. The objects are used to create a specific Hindu Gujarati identity which relates to Portuguese culture. (A photo of such a shrine with a Madonna of Fatima:

https://gulbenkian.pt/en/news/sustainable-development-news/alexandra-i-need-to-talk-to-you/ (accessed on 15 September 2022)).

8. Conclusions

The cult of Our Lady of Fátima has become closely entangled with the history of Portuguese local, regional, and national identity, with Portuguese or lusophone diasporas all over the world, and, most recently, also with non-Christian immigrant communities in the country. The cult is still extremely important for Portuguese Catholics, of which, in 2011, 90% have visited the shrine at Fátima at least once (

Vilaça 2018, p. 73). In the former colonies, Brazilians, Angolans, Mozambiquans, Indians, or Catholics in Macao, China have embraced and taken possession of the cult of Our Lady of Fátima and its local representations. And, finally, many communities all over the world have been established around the cult, which have no relation whatsoever to Portugal or the Portuguese colonial empire. In some cases, it was the anti-communist message that attracted some groups during the Cold War. But a global history of the cult of Our Lady of Fátima needs to look further in order to explain this fascinating development.