From Abstract Form to Concrete Materialization: An Analysis of Mazu’s Image in Statues and Images

Abstract

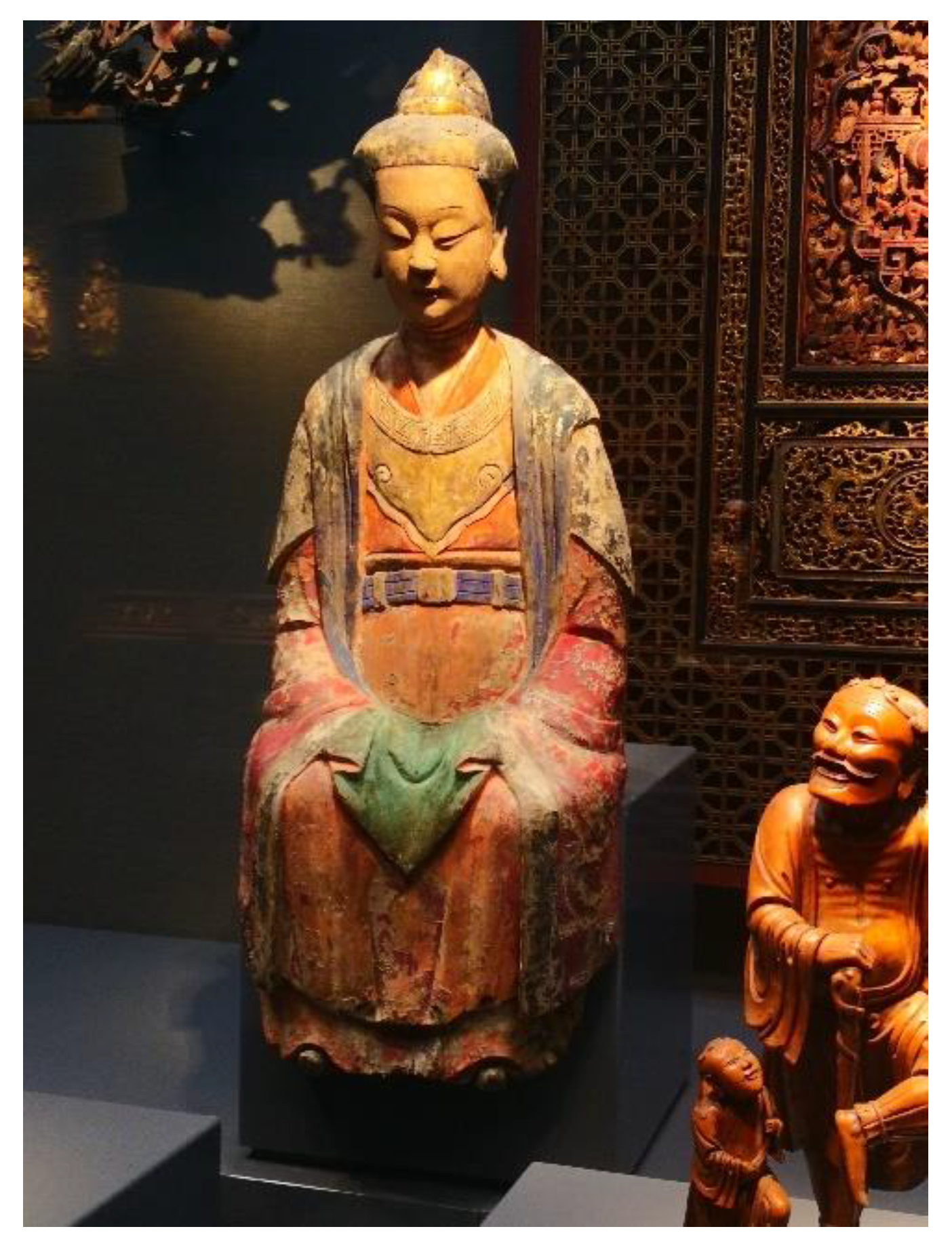

1. Definition of “Mazu Figure” and “Mazu Image”

2. Figure of the “Homeland God” and the Initial Mazu Image

2.1. “Homeland God”: The Mazu Image Is “Loved and Respected as One’s Mother (ai jing rumu 愛敬如母)”

2.2. The Initial Mazu Image: The Same Form of God and Human (shenren tongxing 神人同形)

3. Figure of “Official God” and Mazu’s Transformation Image

3.1. “The Official God”: Mazu Image “Worshipped as an Official (zunfeng ru guan 尊奉如官)”

3.2. Mazu’s Transformation Image: Hundreds of Infinite Forms (bai wu dingshi 百無定式)

4. Figure of “Maritime God” and the Typical Mazu Image

4.1. “Maritime God”: Mazu Image in “the Image of God and Things (shenwu xiangtong 神物象通)”

4.2. The Typical Mazu Image: The Golden Body Is Like One (jinshen ru yi 金身如一)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boltz, Judith Magee. 1986. In Homage to T’ien-fei. Journal of the American Oriental Society 106: 211–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Rongming 陳容明. 2006. Mazu de chusheng he chushen 媽祖的出生和出身 (The Birth and Origin of Mazu). Paper presented at the 2006 Nian Zhonghua Mazu Wenhua Xueshu Luntan Huiyi Lunwen 2006年中華媽祖文化學術論壇會議論文, Tianjin, China, September 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Wangdao 陳望道. 2007. Mazu Xinyang Shi Yanjiu 媽祖信仰史研究 (A Study of the History of Mazu’s Faith). Fuzhou: Haifeng Chubanshe 海風出版社, p. 265. [Google Scholar]

- Dubose, Hampden Coit. 1887. The Dragon, Image, and Demon: Or, The Three Religions of China; Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism, Giving an Account of the Mythology, Idolatry, and Demonolatry of the Chinese. London: Samuel William Partridge and Company Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Yansun 黃岩孫. 1989. Xianxi Zhi (Juan San) 仙溪志(卷三) (Gazetteer of Xianxi, Volume 3). Xianyou Xian Wenshi Xuehui Dianxiao 仙游縣文史學會點校. Fujian: Fujian Renmin Chubanshe 福建人民出版社, p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Weinuo 金維諾. 2011. Zhongguo Siguan Bihua Quanji (Juan San): Mingqing Siguan Shuilu Fahui Tu 中國寺觀壁畫全集(卷3): 明清寺觀水陸法會圖 (The Complete Collection of Chinese Temple Murals (Volume 3): Paintings for Religion Rituals at Ming and Qing dynasty temples land puja). Guangzhou: Guangdong Jiaoyu Chubanshe 廣東教育出版社, pp. 69, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Guosen 柯國森. 1991. Putian Xian Zongjiao Zhi 莆田縣宗教志 (Religious Records of Putian County). Putian: Putian Xian Shiwu Zongjiao Ju 莆田縣事務宗教局, p. 350. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Xianzhang 李獻璋. 1995. Mazu Xinyang Yanjiu 媽祖信仰研究 (Research on the Cult of Mazu). Macau: Macau Haishi Bowu Guan Chubian 澳門海事博物館出版. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Bozhong 李伯重. 1997. “Xiangtu Zhi Shen”, “Gongwu Zhi Shen” yu “Haishang Zhi Shen”: Mazu Xingxiang de Yanbian “鄉土之神”、“公務之神”與“海商之神”: 媽祖形象的演變 (“Homeland God”, “Official God”, and “Maritime God”: The Evolution of Mazu Image). Zhongguo Shehui Jingji Shi Yanjiu 中國社會經濟史研究 2: 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Bozhong 李伯重. 2004. Qianli Shixue Wencun 千里史學文存 (A Thousand Miles of History and Literature). Hangzhou: Hangzhou Chubanshe 杭州出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, Zhenbiao 連鎮標. 2005. Duoyuan Fuhe de Zongjiao Wenhua Yixiang——Linshui Furen Xingxiang Tankao 多元複合的宗教文化意象——臨水夫人形象探考 (A Multifaceted Religious Cultural Imagery—An Exploration of the Image of Lady Lin Shui). Shijie Zongjiao Yanjiu 世界宗教研究 1: 132. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Kejia 梁克家. 2000. Sanshanzhi (Juan Jiu) 三山志 (卷九) (Gazetteer of Three Mountains, Volume 9). Fuzhou: Haifeng Chubanshe 海風出版社, p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Meirong 林美容. 2003. Taiwan Mazu Xingxiang De Xian Yu Yin 臺灣媽祖形像的顯與隱 (The Explicit and Concealed Image of Mazu in Taiwan). Wenhua Zazhi 文化雜誌 48: 131–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Ruikai 林瑞愷. 2020. Dangdai Taihai Guanxi Xia De Mazu Xingxiang Jiangou: Yichang Jieyan Housu Ao Yumin De Jiti Chaosheng Xingdong 當代台海關係下的媽祖形象建構: 一場解嚴後蘇澳漁民的集體朝聖行動 (The Image-Building of Matsu in the Morden Cross-Strait Relationship: A Study of the Su’ao Fishers’ Pilgrimage after the Lifting of Martial Law in Taiwan). Si Yu Yan: Renwen Yu Shehui Kexue Qikan 思與言: 人文與社會科學期刊 2: 53–103. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Ji 劉基. 1999. Liuji Ji (Juan Shier) 劉基集 (卷十二) (Liu Ji Collection, Volume 12). Lin jiali Dianjiao 林家驪點校. Hangzhou: Zhejiang Guji Chubanshe 浙江古籍出版社, p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Kezhuang 劉克莊. 2011. Liu Kezhuang ji jianjiao (Juan Sishiba) 劉克莊集箋校(卷四十八) (The Collation and Comment of Liu Kezhuang’s Anthology, Volume 48). Xin Gengru Jianjiao 辛更儒箋校. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局, p. 2467. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, Vivienne. 1993. The Legend of the Lady of Linshui. Journal of Chinese Religions 21: 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptak, Roderich, and Jiehua Cai. 2017. The Mazu inscription of Chiwan (1464) and the early Ming voyages. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 167: 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruitenbeek, Klaas. 1998. Mazu, the God of Sea Protection in Paintings and Woodcuts, Proceedings of the 1995 Macao Seminar on the History and Culture of Mazu Faith. Macao: Museu Marítimo and Macao Cultural Studies Association, p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- Sangren, P. Steven. 1983. Female Gender in Chinese Religious Symbols: Kuan Yin, Ma Tsu, and the” Eternal Mother”. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 9: 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schottenhammer, Angela. 2010. Brokers and “Guild” (huiguan 會館) Organizations in China’s Maritime Trade with her Eastern Neighbours during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Crossroads 1: 99–150. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Lian 宋濂. 1976. Yuanshi (Juan Shi) 元史 (卷十) (History of the Yuan Dynasty, Volume 10). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局, p. 204. [Google Scholar]

- Tuojin 托津. 1991. Qinding daqing huidian shili (Jiaqing Chao) (Juan Sanbai Liushier) 欽定大清會典事例(嘉慶朝)(卷三百六十二) (Collected Statutes of the Qing during the Reign of Jiaqing, Volume 362). Taipei: Wenhai Chubanshe 文海出版社, p. 6076. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yingying 王英暎. 2014. Fujian Minjian Shengji Tu Zhong Mazu Xingxiang De Duochong Juese 福建民間聖跡圖中媽祖形象的多重角色 (The Multiple Roles of Mazu Images in Fujian Folk Sagely manifestation Pictures). Meishu Guancha 美術觀察 8: 114–17. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Zhaojiu 謝肇淛. 1935. Wuzazu (Juan Shiwu) 五雜俎(卷十五) (Five Assorted Offerings, Volume 15). Shanghai: Zhongyang Shudian 中央書店, pp. 289–90. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, He 謝赫, and Zui Yao 姚最. 1959. Guhua Pinlu 古畫品錄 (Record of Classification of Ancient Paintings). Wang Bomin Biaodian Zhuyi 王伯敏標點注譯. Beijing: Renmin Meishu Chubanshe 人民美術出版社, pp. 1, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Liang 楊倞. 2014. Xun Zi (Juan Shiyi) 荀子(卷十一). Geng Yun Biaojiao 耿芸標校. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe 上海古籍出版社, p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Mingsheng 葉明生. 2010. Linshui Furen yu Mazu Xinyang Guanxi Xintan 臨水夫人與媽祖信仰關係新探 (A New Study on the Relationship between Lady Linshui and Mazu’s Beliefs). Shijie Zongjiao Yanjiu 世界宗教研究 5: 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Xingguo 葉興國, and Guoyu Zhang 張國玉. 1997. Ninghua Xian Chengqu Tianhou Gong de Chuantong Miaohui甯化縣城區天后宮的傳統廟會 (Traditional Temple Festivals at Tin Hau Temple in the urban area of Ninghua County), Ninghua Wenshi Ziliao (Di Shibaji) 甯化文史資料 (第十八輯) (Ninghua Cultural and Historical Materials (18th Series)). Fujian: Ninghua Yizhong Yinshuachang Yin 甯化一中印刷廠印, p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Rongmin 余榮敏. 2007. Nüquan Shijiao xia de Mazu Xingxiang Jiedu 女權視角下的媽祖形象解讀 (Interpretation of Mazu’s Image from the Perspective of Feminism). Fujian Sheng Shehui Zhuyi Xueyuan Xuebao 福建省社會主義學院學報 4: 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Wei 張瑋. 1985. Dajin Liji (Juan Ershijiu) 大金集禮(卷二十九) (Collection of Rituals of Great Jin Dynasty, Volume 29). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局, p. 251. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Tingyu 張廷玉. 2013. Mingshi (Juan Liushiliu) 明史(卷六十六) (History of the Ming Dynasty, Volume 66). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局, pp. 1621–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yanchao. 2019. The State Canonization of Mazu: Bringing the Notion of Imperial Metaphor into Conversation with the Personal Model. Religions 10: 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Zhiren 鄭智仁. 2013. Aomen Xiandai Shige Zhong De Mazu Yixiang Tanjiu 澳門現代詩歌中的媽祖意象探究 (A Study on Mazu Imagery of Modern poetry in Macao). Zhongguo Xiandai Wenxue 中國現代文學 24: 147–66. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, B.; Shu, X. From Abstract Form to Concrete Materialization: An Analysis of Mazu’s Image in Statues and Images. Religions 2022, 13, 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111035

Zhang B, Shu X. From Abstract Form to Concrete Materialization: An Analysis of Mazu’s Image in Statues and Images. Religions. 2022; 13(11):1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111035

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Beibei, and Xiaping Shu. 2022. "From Abstract Form to Concrete Materialization: An Analysis of Mazu’s Image in Statues and Images" Religions 13, no. 11: 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111035

APA StyleZhang, B., & Shu, X. (2022). From Abstract Form to Concrete Materialization: An Analysis of Mazu’s Image in Statues and Images. Religions, 13(11), 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111035