1. Introduction

Trade Gods 行业神 were spiritual symbols of traditional guild organizations in medieval China. They represented a popular religious belief that was commonly seen both in the folk and the court

1. In traditional Chinese society, people from all walks of life worship their Ancestor God and Protector God (

Deng 2018, pp. 119–32, 156). Trade gods are unique in the extremely complicated system of worship in Chinese folk belief. “Trade Gods” are gods whom practitioner worship and that have some kind of relationship with the trade they are in. For example, sericulture practitioners worship the silkworm deity, people in the printing and dyeing trade worship the Dyeing-vat-God 染布缸神, silk weavers worship the Huang-Dao-Po 黄道婆, etc. Such beliefs and relevant activities are an important part of the folk culture of beliefs, with strong Chinese and industrial characteristics. Agricultural production began to have advantages and the social division of labor it produced was a prerequisite for the emergence of the Trade Gods. It can be said that human division of labor created a god with trade characteristics.

Silkworm deity is the Trade God worshipped by sericulture practitioners in Medieval China. People believed that the silkworm deity is both the inventor of sericulture and the protector of silkworm affairs. The worship of silkworm deity can realize the integration and maintenance of sericulture organizations between different classes and regions through belief in ancestor Gods and sacrificial ceremonies. The expression of silkworm deity as a form of image art first appeared in Han Dynasty (BC.202–CE.220) stone reliefs (

Figure 1). It belongs to the first picture at the top of the grid area on the left gate post in a set of five Han Dynasty tomb door stone relief. On the left is Lei-Zu, wearing a flat top hat, sitting on the front of the robe, three strands of silk thread spitting out of her mouth, the left arm lying forward on the left leg, the right arm bending upward, and an arc-shaped silk thread left from the right shoulder to the right leg which indicates that the silkworm deity is drawing silk out of her mouth. On the right is the silkworm officer, wearing a Jin Xian crown, sitting on the side with a robe on his back, and holding a bundle of silk thread in his right hand; he is responsible for collecting and winding silk.

After that, based on the creation and popularization of woodblock printing, the silkworm deity spread widely through ancient Chinese society in the form of art. Woodblock prints and illustrations of block-printed books are the material carriers of such art, and both use the same processing method. The silkworm deity image in the woodblock prints is represented by painting or in combination with simple words, and usually exists independently. The illustrations usually exist in a book. Such books are characterized by a combination of paintings and narrations. The image of the silkworm deity is always accompanied by text describing its name, origin, and the plots of some narrative stories about the silkworm deity, so they are more complete and detailed than the woodblock prints.

The wood engravings “Silkworm Mother” and “San-Gu Zhi Can” (

Figure 2) from the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127) are the first two woodblock paintings depicting the silkworm deity. “Silkworm Mother” is a printed product, which was printed on soft paper in four colors of thick or light ink, including vermilion and light green. The picture is mainly composed of the silkworm mother, silkworm cocoon, and auspicious patterns. The word group “silkworm mother” is printed at the top left of the picture. On the right side of the picture, there are cocoons all over the basket. “San-Gu Zhi Can” is a woodblock carved into a row of three female statues sitting side by side with hats. The female statues in the middle wear round hats and the female statues on both sides wear fan-shaped hats. The left side of the screen is engraved with a column of six words “San-Gu Zhi Can Da Ji 三姑置蚕大吉”, and the right side is engraved with a column of seven words “Shou Qian Jin Bai Liang Da Ji 收千斤百两大吉”. The function is speculated to be used to print woodblock New Year pictures used in worship of the folk silkworm deity in the Song Dynasty (960–1279).

It can be seen that in a small branch of medieval Chinese religious art, images of the silkworm deity in ancient art carry rich cultural information on silkworm deity worship. They clearly depict the sexual distinction, movement, dress, and tools, and scenes of participating in worship of the silkworm deity. These are the kind of material cultural “remains” that are more helpful than oral legends for exploring the images and types of silkworm deity in medieval China, and studying the ceremonies involved in Chinese traditional silkworm deity worship.

In recent years, academic research on the worship of the silkworm deity can be divided into three categories. The first category of research explores the history, origin, and customs of the worship of the silkworm deity from the perspective of identity textual research. Through textual research on the corresponding relationship between Xian-Can 先蚕 and Tiansi 天驷 constellation, Huang Weihua believes that the worship of the silkworm deity is related to fertility worship (

Huang 1998, pp. 160–61), which emphasizes the reproductive worship consciousness of ancient Chinese ancestors. Through textual research on the 10 silkworm deities listed in Dunhuang document s.5639 “

Silkworm Extended Prayer Text 蚕延愿文”, Zhao Yuping believes that the praying objects in Dunhuang Buddhist ritual books are the embodiment of the folk transformation of Buddhism after it was introduced into Chinese society (

Zhao 2015, pp. 49–57), which highlights the rich and changing imagery of the silkworm deity with the change of dynasties. Wang Yan believes that the silkworm deity worshipped by all dynasties is different, resulting in great differences of opinion on the identity of the silkworm deity among scholars today. Therefore, taking historical documents as a starting point, she examines the identity changes of the silkworm deity in different dynasties (

Wang 2017, pp. 88–90), the aim being to trace the identity of the silkworm deity through historical documents. Guo Chao started by confirming the authenticity of the records of Lei-Zu 嫘祖 in ancient documents to explore Lei-Zu’s identity as a silkworm deity (

Guo 2017, pp. 95–100); Lei-Zu’s creation and promotion of silkworm activities are emphasized.

The second category of research explores the regional cultural differences in silkworm deity worship through myths, folklore, and ballads. Starting with Huzhou folklore, Hu Ming investigated the “Lei-Zu”, “Ma-Tou-Niang 马头娘”, “Ma-Ming-Wang 马明王”, and “Can Hua Wu Sheng 蚕花五圣” believed by Huzhou silk practitioners, and summarized the diversity of and symbolic differences in silkworm deity images in Huzhou (

Hu 2013, pp. 113–14); the focus was on the legend content and the images of the silkworm deity. From the perspective of analyzing the story plot, Xiao Fang studied the culture of belief in a silkworm deity in southern Shanxi during the Ming and Qing Dynasties, focusing on the image of “San Can Sheng Mu 三蚕圣母” in the story of

Silkworm deity Offering Silk 蚕神献丝 and the contemporary sacrificial system (

Xiao 2021, pp. 94–103), paying more attention to the custom culture contained in the silkworm deity story itself. From the perspective of sericulture ballads in the Taihu Lake basin, Liu Xuqing studied the images of “Ma-Ming-Wang Bodhisattva 马明王菩萨” and “Can Hua Goddess 蚕花娘娘” in the folk silkworm deity presented in the ballads, as well as sacrificial customs (

Liu 2021, pp. 18–25), focusing attention on the agricultural customs and life customs related to the silkworm deity in folk songs.

The third category of research explores silkworm deity sacrifices from the perspective of ritual order. Liu Lu studied the court’s Xian-Can 先蚕 ceremony in the Qing Dynasty (1636–1912), exploring the political environment, the importance of the ruling class to sericulture, the status of Lei-Zu under the different etiquette structures of the emperor and empress, and the significance of the establishment of the Xian-Can ceremony (

Liu 1995, pp. 28–33). The emphasis was on the embodiment of Manchu’s gradual Sinicization in the Xian-Can ceremony. Xu Tingting took the Xian-Can worship system of the court during the Jia-jing period (1522–1566) as a starting point, exploring the orderly ritual of Xian-Can worship, including the etiquette of picking mulberry leaves, banquets, the etiquette of picking cocoons, and the interpretation of the double interaction between the ritual system and culture in courtly and folk worship of the silkworm deity (

Xu 2018, pp. 43–49), and highlighting the significance of the court’s Xian-Can ceremony for ordinary people.

Additionally, some researchers chose to explore the development of the relationship between silkworm deity worship and sericulture from the perspective of production activities and the commodity economy. Yang Hu took the activities of sericulture and silk reeling in Jiangnan and the reform of the town economy as the starting point in the Ming Dynasty, and discussed the support and promotion of the development of silk commercialization in relation to the sacrificial activities of the silk trade (

Yang 2014, pp. 211–15), focusing on the relationship between the centralized and large-scale development of silk production and the formation of the culture of silkworm deity worship.

Overall, the existing research in this field discusses the identity, characteristics, and ritual activities around silkworm deity worship from both folk and court perspectives. However, most of them focus on a single silkworm deity, or a number of silkworm deities popular in a certain region, but there is not yet a complete medieval Chinese silkworm deity system. Meanwhile, existing research materials in this field mainly come from the written records in the form of ancient documents, with the etiquette and customs of oral narrative showing up in ballads and traditional operas, while ancient artworks have only occasionally been used as circumstantial evidence, so we are lacking experience in the interpretation of silkworm deity imagery from the perspective of iconology. However, in medieval China, the purpose of art was to record, prompt, display, or corroborate texts. Art is, therefore, an important component of silkworm worship, and also serves as direct evidence. It can even depict a relatively complete silkworm deity worship system with its own themes, expression, symbols, and narrative, which is quite reliable and precious.

Silkworm deities were created by sericulturists by selecting multiple objects from known materials as sources. These may have come from the transformation of characters and objects that intersect with sericulture in the official history, or from the transformation of natural objects seen in production, or from the transformation of the three major religious gods or other folk gods from religious books, legends, myths, and ballads. Although some silkworm deities are imaginary, others are more or less related to sericulture, and so can be found in the literature of medieval China.

From the perspective of iconology, this paper collects and classifies art from the Han Dynasty to the Yuan Dynasty, including silkworm deities or worship ceremonies, and selects representative silkworm deity images. Secondly, it confirms the name of the silkworm deity by combining the images and the relevant textual descriptions in ancient documents, discussing its imagery, classification, and identity, analyzing its origin, and assessing its relevance to three major religious cultures. Finally, we restore the content of the image to the narrative scene, determine the development context of silkworm worship, study its symbolism and narrative and the differences between official and folk worship activities, and interpret its religious symbols and cultural significance.

2. Worship of the Silkworm Deity in Medieval China

Most of the guilds in ancient China were automatically formed by craftsmen, merchants, and farmers, because they adapted to their respective production and living environments, or evolved from blood-related groups that monopolized a kind of handicraft technology (

Quan 2007, pp. 1–9). The records of guilds first appeared in the Sui and Tang Dynasties, when folk handicrafts and commerce were developed. In the Sui Dynasty (581–618 CE), according to the new records of

Liang Jing Xin Ji 两京新记, there were reports of the location and number of “Hang 行” and “Xingpu 行铺” (

Wei 2020, p. 156) in Luoyang 洛阳, the eastern capital. By the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), the scale of the guild of Luoyang had developed to “220” (

Song 2013, p. 291), and, on this basis, an industry habit of avoiding free competition through trade rules was formed (

Quan 2007, p. 40).

The formation of silk guilds stems from the prosperity of sericulture. Sericulture is an important part of the ancient handicraft industry in China. It gradually became independent since the agricultural differentiation in the spring and autumn (770–476 BCE). The “Bao Bu Mao Si 抱布贸丝” (

Mao 2018, p. 84) in the

Shi Jing 诗经 is the earliest record of the trading link of silk commodities. Because the lifespan of fresh cocoons is relatively short, reeling must be carried out within seven or eight days after coming down from the cluster. Once the pupa in the cocoon turns into a moth, reeling cannot be carried out. Therefore, reeling production needs to be carried out directly in the silkworm breeding park. Due to the particularity of cocoon and silk production, cocoons are not suitable for transportation to independent manual workshops for centralized processing. In medieval China, silk reeling and sericulture were usually inseparable. Therefore, both farmers who grow mulberries and rear silkworms and artisans who reel silk are called sericulturists, that is, sericulture practitioners.

As the worship of Trade Gods is a means to increase the unity of guilds, the worship of the silkworm deity appeared with the emergence of sericulture. The worship of the silkworm deity is a small branch of “folk religion”. It is based on the sericulture organization and the family organization of sericulturists in the same region. It is a seasonal, sacrificial ceremony accompanying the silk harvest and production. It can be seen from the ancient written word and art records that the worship of the silkworm deity is part of a fairly systematic world outlook. The worship of the silkworm deity is an embodiment of folk production customs in ancient China. Although the court and folk sericulturists created silkworm deities with different identities, with no single form and title, their function of “blessing silkworm affairs and the silk harvest” unified sericulturists and was closely related to daily production and life.

The formation of sericulture enabled practitioners to have a relatively stable organizational structure. Generally, practitioners in the same region accepted the same silkworm deity and made it popular in medieval Chinese society. Although the worship of the silkworm deity had a broad foundation among the people, it cannot be simply classified as a diffuse, unofficial “little tradition” (

Wang 1997, pp. 157–61) or “peasant religion” (

Wong 2011, pp. 153–70) that is inseparable from the life practice of the general public. Although it is different from the institutional structure of the three major religions, it also has the characteristics of a “great tradition” (

Wang 1997, pp. 157–61) or “elite religion” (

Wong 2011, pp. 153–70), such as being officially recognized, institutionalized, recorded in writing and images, and being supported by the upper class. The worship of the silkworm deity was also officially recognized by way of the empress’s sacrificial ceremony, which was popularized among practitioners of the folk religion, forming the custom of sacrificing and thanksgiving, and closely connecting “great tradition” with “little tradition”. We can, therefore, regard it as a relatively unified religious consciousness formed by silkworm deity believers.

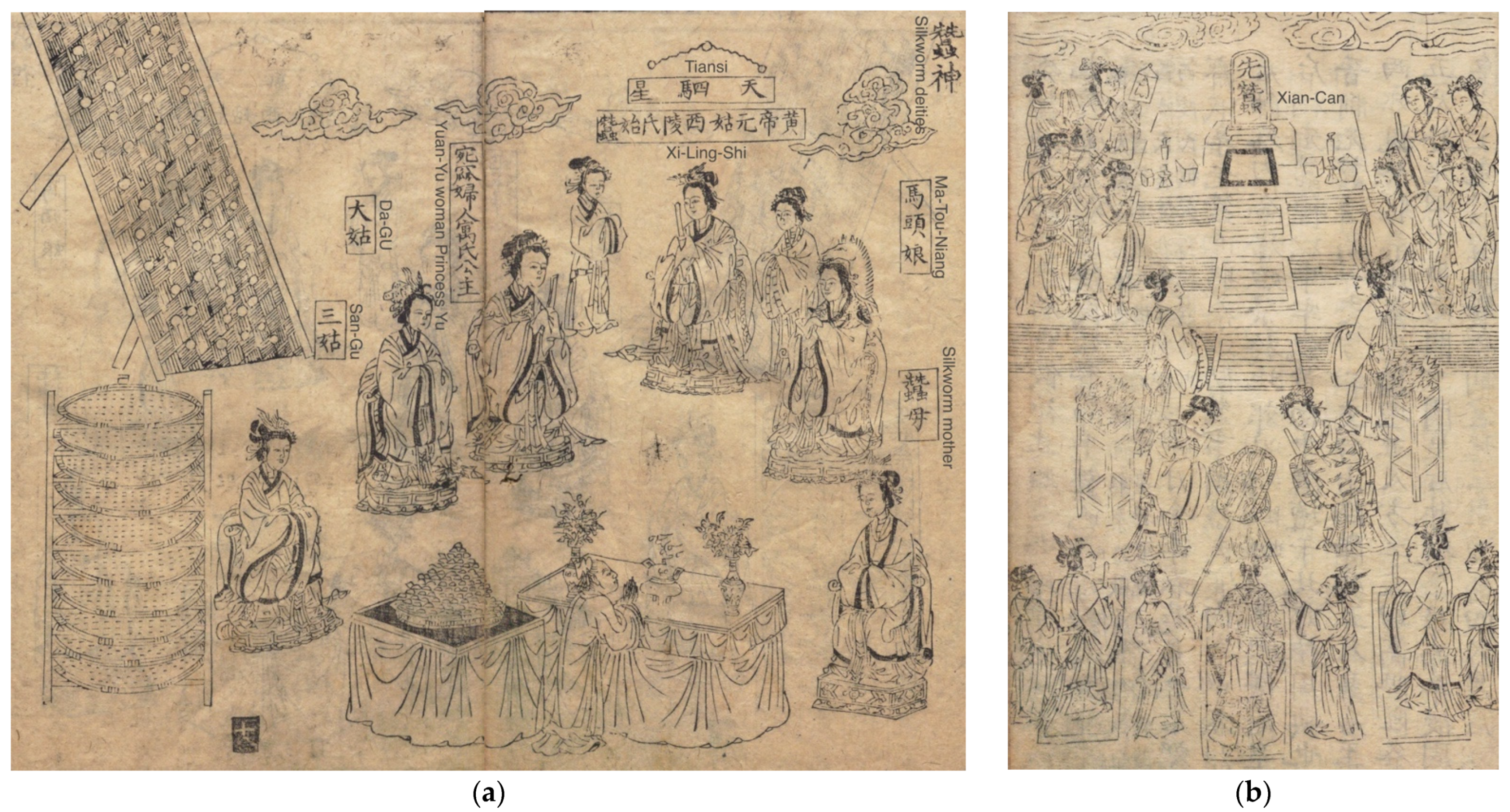

Most images related to the worship of the silkworm deity are usually used to depict the image of the silkworm deity alone, or to comprehensively express a sacrificial ceremony that includes the silkworm deity, sacrificial places, tools, and rituals. Taking the two illustrations in

Nong Shu 农书 printed in the Yuan Dynasty as an example (

Figure 3), the illustration of the “silkworm deity” depicts nine silkworm deities and one worshipper, making it is the most comprehensive image of the silkworm deity from medieval China. The illustration of “Can Tan 蚕坛” depicts the official sacrificial place “ Xian-Can Tan 先蚕坛”, the sacrificial scene, and the ritualist.

In the illustration, there are nine Silkworm deities surrounding the worship area in a semicircle, reflecting the polytheistic tendency of silkworm deity worship. From left to right, the figures San-Gu 三姑, Da-Gu 大姑, Yuan-Yu woman 菀窳妇人, and Princess Yu 寓氏公主 are located on the left side of the illustration. Xi-Ling-Shi 西陵氏 is located in the middle of the picture, the Tiansi 天驷 constellation is located directly above Xi-Ling-Shi; Tian-Chan 天蚕 Goddess and Di-Sang 地桑 Goddess stand on the left and right sides of Xi-Ling-Shi, respectively, and Ma-Tou-Niang 马头娘 and Silkworm mother are located on the right. The silkworm deity’s position forms a pattern (

Figure 4) where three scattered points gather from the bottom to the upper right, and the focus is the Tiansi constellation. Tiansi is one of the 28 constellations in ancient China. It is called Tiansi because it is composed of four stars. Tiansi was originally regarded as the ancestor of horses, and because the silkworm head is similar to a horse’s head, it is also regarded as the constellation of silkworm ancestors (

Li 2015, pp. 310–15).

As a constellation, Tiansi is painted on the top of all silkworm deities. The bottom of the Tiansi is the visual center of the illustration. Three silkworm deities are painted here, forming a group. From the arrangement position and size, we can see their primary and secondary relationships. Xi-Ling-Shi is also known as Lei-Zu 嫘祖, who is located in the middle and has a considerable position in the Confucian classics, so is called the orthodox Silkworm deity of court sacrifice. There is no clear information about the silkworm deities on either side of Xi-Ling-Shi, but according to the wood engraving “San-Gu Zhi Can 三姑置蚕” (

Figure 2b) from the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127), they may be a combination of three silkworm deities established by folk custom. The silkworm deities known as “Sa-Gu 三姑” in the folk tradition are a combination of Silkworm breeding God, Tian-Chan 天蚕 Goddess, and Di-Sang 地桑 Goddess. This combination is called “San-Can-Gu 三蚕姑” in Weifang and Shandong; it is called “San-Can Goddess (三蚕娘娘)” in Zezhou and Shanxi. They are Lei-Zu, Empress Ma, and Ma-Tou-Niang (

Hu 2011, pp. 203–5). In Yangcheng, Shanxi, which is not far away, it is called “San-Can Sheng Mu 三蚕圣母”, which are Lei-Zu, Mulberry girl, and Ma-Tou-Niang, respectively (

Xiao 2021, pp. 94–103). In the Tang Dynasty, in inscriptions in Yanting and Sichuan, Lei-Zu, Yuan-Yu woman, and Princess Yu are called the three holy images of the Lei-Zu temple.

In the illustration of the silkworm deity, a worshipper and two altars with ritual objects are located in the worship area in the middle of the lower part of the picture. The larger altar is in front of the worshiper, and holds a censer and a pile of vases. Cocoons are stacked in a round bamboo basket like a hill, and placed on the smaller altar, which is located on the side of the worshiper. On the left side of the illustration, there are oblong and round silkworm baskets for sacrificial tools. The silkworm baskets are placed on the silkworm rack, and there are many cocoons clearly visible in the oblong silkworm baskets. It can be seen from the cocoon on the altar that the worshiper is thanking the silkworm deity. This sacrifice requires placing the new cocoon in front of the god after picking, and then the worshiper worships the silkworm deity.

Another illustration of “Can Tan 蚕坛” (

Figure 3b) in

Nong Shu 农书 belongs to a typical official sacrificial image. The illustration depicts a scene of the empress leading imperial concubines, princesses, and courtiers’ wives to sacrifice the Xian-Can in the Xian-Can Tan, reflecting the ruling class’s vision of social enlightenment through silkworm deity worship. The Xian-Can Tan is located in the middle of the picture. It is a square, open-air building built of earth, with steps extending out on all sides. It was the official building designated for the worship of Xian-Can in ancient China. The spirit tablet of the Xian-Can was placed on the top layer, and the god’s position at the center was marked with “Xian-Can 先蚕” to replace the silkworm deity. The empress is in the middle of the lower part of the picture, with imperial concubines, princesses, and courtiers’ wives on both sides, facing the spirit tablet. The ritual officer and musician stand up on both sides of the first silkworm altar in turn.

The court worship of the Xian-Can in ancient China was first recorded in the

Li Ji 礼记 of the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE), in which the empress of the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE) sacrificed Xian-Can in the northern suburbs (

Ruan 2009, p. 3479). During this period, sacrificial sites were built in the northern suburbs. The Xian-Can Tan of the Han Dynasty was built in the eastern suburbs. The Xian-Can Tan is 1 Zhang 丈 high and 2 Zhang square, there are steps on all sides, and the steps are 5 chi 尺 wide (

Fang 1974, p. 590). In the Sui and Tang Dynasties, Xian-Can Tan was built in the northern suburbs, and in the Song Dynasty, Xian-Can Tan was built in the eastern suburbs. The Xian-Can Tan in the Song Dynasty was 5 Chi high and 2 Zhang square, with steps on all sides, each 5 Chi wide (

Tuo 1985, p. 2494).

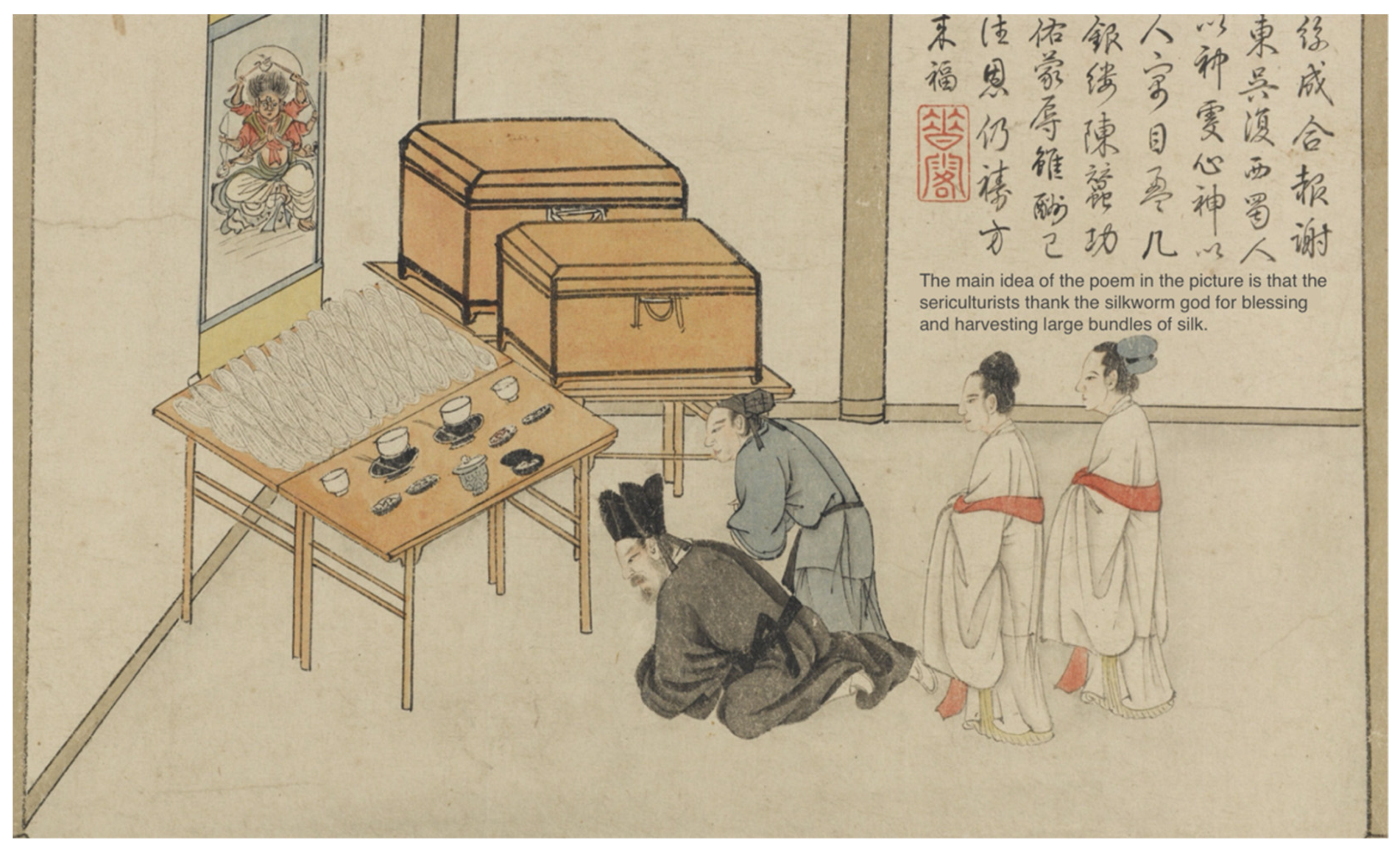

However, the scene of silkworm worship “A picture of Farming and Weaving 耕织图” (

Figure 5), painted by Cheng Qi in the Yuan Dynasty, is completely different from the “Can Tan”, showing a folk silkworm worship scene with the family as the organizational unit. The sacrificial scene is located indoors, with the portrait of the silkworm deity hanging on the wall. The silkworm deity in the portrait is male, with a third eye in the middle of the eyebrows, six of the eight arms holding bows and swords, and hands folded in front of the chest, which means that it looks like the Horse God. There are two altars at the bottom. The altar near the wall is neatly arranged with many bundles of silk, and the other altar is laid with chopsticks, wine cups, and sacrificial dishes. Two male worshipers are located in front of the table, the kneeling before the male master. The two women stand behind the men with a respectful posture.

The illustrations “Silkworm deity “and “Can Tan 蚕坛” are two of the illustrations of silkworm affairs in the Agricultural Book. The sacrificial images in “A picture of Farming and Weaving 耕织图” also belong to the lineage of silk production. The location is based on the actual production sequence of silkworm rearing and reeling. From the sequence of these three images and images showing other production links, the worship activities shown in the illustrations of “Silkworm deity “and “Can Tan” are ahead of all silkworm production links, reflecting the ritual of “sacrificing to the Silkworm deity”—that is, silk worship activities are held on the day when the silkworm cocoons hatch. The worship scene in “A picture of Farming and Weaving” takes place after the silkworm cocoon harvesting and silk reeling processes, as there are many bunches of silk on the offering table. It can be seen that it reflects the ceremony of “thanking the Silkworm deity”—that is, worship activities after the silk reeling. During the worship, the silk is usually placed on the altar, and then, the silkworm deity is asked to bless the successful completion of the silkworm activities.

3. “Ma-Tou-Niang 马头娘” Based on the Myth of “Girl Becomes Silkworm”

The silkworm needs to go through four stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult, This metamorphosis had been endowed with divinity before the Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE) in China

5. The original silkworm deity was part of the “animal worship” of human beings in the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE) or earlier. It is based on spirit worship with zoomorphic characteristics, and is also an example of “animism”. People prayed to the silkworm deity for a good harvest of silk through sacrificial activities. The oracle inscriptions of the Shang Dynasty for sacrificing to the silkworm deity were recorded as “Can Shi San Niu 蚕示三牛” (

Hu 1972, pp. 2–7, 36, 72), which means that sacrificing to the silkworm deity requires three cows. There is no specific image description, but ceremonial jades based on silkworms were common in ancient China.

With the progress of civilization, images of gods based on animals were gradually given more human characteristics, and the image of the silkworm deity was gradually humanized through myth. This stage began at the end of the Warring States period (403–221 BCE). The Confucian scholar Xun Zi 荀子 proposed that the silkworm’s body was like a woman’s and the head was like a horse’s (

Xun 1983, p. 359).

Shan Hai Jing 山海经 also mentioned that a woman knelt in front of a mulberry tree to spit silk in the “Ou Si Zhi Ye 欧丝之野” (

Guo 2010, p. 4911). Although it was not deified or given a divine name, it was indeed the earliest record of the silkworm having human characteristics and evolved into a myth.

The myth with the theme of “silkworm girl 蚕女” gradually evolved into “Girl Becomes Silkworm 女子化蚕” in the Jin Dynasty (266–420 CE). There was also the myth of a “silkworm horse 蚕马”

6 (

Gan 2019, p. 335) in

Sou Shen Ji 搜神记. The storyline units are as follows:

Unit 1: The father went away to war far away, leaving only his daughter and a horse she raised.

Unit 2: The daughter missed her father and promised to marry whoever could save her father.

Unit 3: The horse heard the daughter’s oath and went to the enemy camp to take her father home.

Unit 4: The daughter told her father of her promise. The father broke the promise and shot the horse, stripping it of its skin and exposing it to the sun.

Unit 5: One day, while the father was away, the daughter told the neighbor that the horse was asking for trouble, and the horsehide wrapped itself around the daughter and they flew away. When the father came home, he was told by the neighbor, but failed to find his daughter.

7Unit 6: The horse and his daughter stopped at a mulberry tree, transformed into silkworms, fed on mulberry leaves, and made silk and cocoons.

During the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), a new plot was added at the end of the “silkworm horse” story:

Unit 7: One day, the daughter fell from the sky on a horse and told her parents that because of her contributions, the “Tai-Shang 太上” appointed her a fairy female celestial.

Unit 8: After that, the folk in Sichuan began to worship the silkworm deity, named after the “Ma-Tou-Niang”, and the statue of a young woman in horsehide.

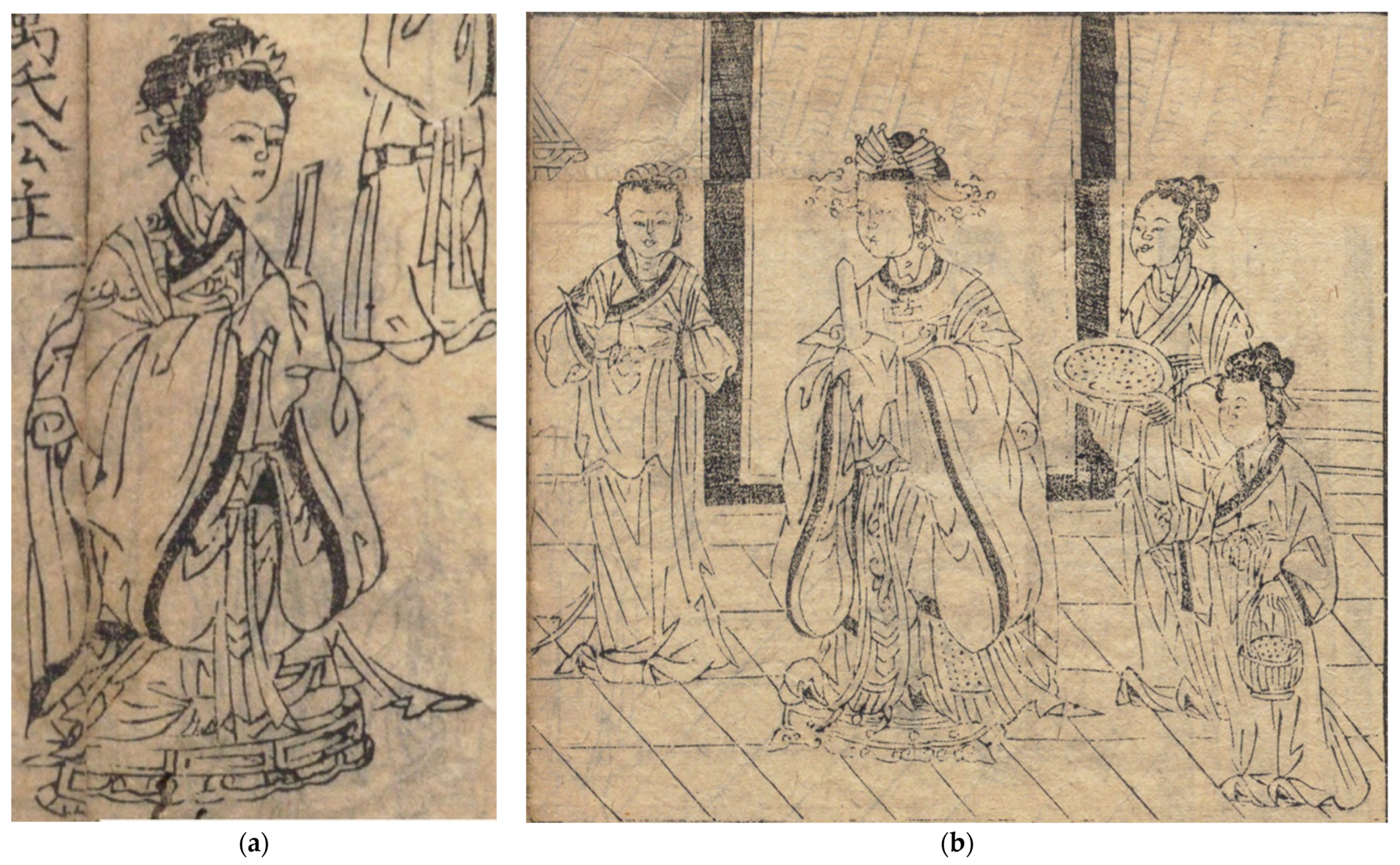

As a written narrative method, the myth of “Girl Becomes Silkworm” tells the origin of the folk silkworm deity “Ma-Tou-Niang 马头娘”, and the ancient illustrations drawn with the image of the daughter in the myth become the witness and support of the myth. The image of “Ma-Tou-Niang” (

Figure 6a) in the illustrations of “Silkworm deity” in

Nong Shu 农书 depict the image of Ma-Tou-Niang as a girl wearing a horsehide. In the Yuan Dynasty, the horse’s head is like a hat on the girl’s head. The popularity of Ma-Tou-Niang and the custom of its worship among the people is the embodiment of the symbolism of the silkworm deity in the myth of “Girl Becomes Silkworm”, and it is also an important strand of the evolution of the image of the Silkworm deity. The image of Ma-Tou-Niang in the

Nong Shu 农书 is very different from the illustrations of “silkworm women” in

San Jiao Yuan Liu Sou Shen Da Quan 三教源流搜神大全 (

Figure 6b). In the

Nong Shu 农书, the girl is wrapped in a horsehide behind her back, and the girl and horse are integrated into one, which is the same as described in the myth of the “silkworm horse 蚕马” in the Jin Dynasty. The image of Ma-Tou-Niang in the “silkworm women” is that the girl is standing to the side of the horse, and they are separate from each other.

At the end of the myth of “Girl Becomes Silkworm”, the “Tai Shang 太上” perceived the merit of the daughter and appointed her as the “Jiu Gong Xian Pin 九宫仙嫔”. Since then, the daughter has changed her identity from a folk woman to a fairy who can accept sericulturist worship. This ending has been processed and modified by Taoist culture. The full name of the “Tai Shang 太上” is “Tai Shang Lao Jun 太上老君 (Lord Lao Zi)”, which is one of the Taoist “Sanqing 三清” gods, “Dao De Tian Zun 道德天尊”. The Tai Shang granted immortality to the daughter, thus adding Ma-Tou-Niang to the Taoist Divine system. For example, Huayang palace 华阳宫, a Taoist temple located in Huashan and Jinan worships the statue of Ma-Tou-Niang (

Figure 7b) in the Mian-Hua-Dian 棉花殿 in the palace, which integrates the folk silkworm deity into the Taoist system. This not only reflects the penetration of Taoism into folk beliefs, but also shows that the secularization of Taoism promotes the prosperity of silkworm deity worship. The Ma-Tou-Niang of the statue rides on a horse, which is closer to the “silkworm horse” myth of “the daughter falls from the sky on a horse” from the Tang Dynasty.

The other names of Ma-Tou-Niang are “Ma-Ming Bodhisattva 马明菩萨” (

Dai 2019, p. 273), “Ma-Ming-Wang 马明王” (

Yao 2015, p. 43), “Horse face Bodhisattva 马面菩萨”, “Ma-Ming-Wang 马鸣王”, and “Ma-Ming Bodhisattva 马鸣菩萨” (

Zhou 2013, p. 40). Although the name has obvious Buddhist origins, the image is still of a woman riding a horse. For example, the folk New Year pictures from Suzhou are full of silkworms, as in “Can Hua Mao Sheng 蚕花茂盛” (

Figure 7b), which shows a woman holding a basket of cocoons and riding forward. The maidservant behind her holds a flag with “Ma-Ming-Wang” written on it.

In folk religion, the identity of Ma-Ming-Wang does not belong to the Buddhist system; rather, she is a folk goddess conferred by the emperor, which has legitimacy. In Zhicun, Zhejiang, sericulturists recalled that “the emperor of the Song Dynasty (960–1297) encouraged sericulture, specially appointed the silkworm goddess Ma-Ming-Wang Bodhisattva as the “Ma-Ming Da Shi 马鸣大士”, and ordered the silkworm breeding area to build a temple to worship her. Therefore, Zhicun sericulturist built a Long-Can temple to worship Ma-Ming-Wang behind the Land-temple. The legend spread in Zhicun that the emperor of Song Dynasty, in conferring the title of “Ma-Ming Da Shi”, was obviously influenced by Confucian orthodoxy, and so it was necessary for the emperor to consolidate the identity of the silkworm deity. It can be seen that the silkworm deity was integrated into Confucianism in the process of identity change.

In the narrative folk song “Ma-Ming-Wang Bodhisattva 马明王菩萨” from Haiyan and Zhejiang (

Gu 1991, p. 54), Ma-Ming-Wang is localized and belongs to “Yiwu, Dongyang”. The lyrics of “Ma-Ming-Wang Bodhisattva” are as follows:

- Ma-Ming-Wang Bodhisattva comes to the door,

- Mounts the lotus platform on a white horse.

- Ma-Ming-Wang Bodhisattva did not appear this year,

- There’s a long history,

- From the Song Dynasty to now.

- Where did Ma-Ming-Wang Bodhisattva come from?

- She came from Yiwu, Dongyang.

Another folk narrative song “Can Hua Shu 蚕花书” in Haiyan, attributed the Ma-Ming-Wang Bodhisattva to the Taoist deity system. The plot units of the ballad are as follows:

Unit 1: Zheng Baiwan 郑百万 went to Xifan 西番 country to fight and was trapped.

Unit 2: His wife vowed that whoever could save Zheng Baiwan could marry her three daughters.

Unit 3: The white horse brought Zheng Baiwan home.

Unit 4: The white horse asked to marry the third daughter, but Zheng Baiwan did not agree. He killed the white horse and hung its skin in the yard.

Unit 5: When the third daughter was looking at the horsehide in the yard, she was swept away by the horsehide and died in the mulberry garden, reincarnating as a flower silkworm.

Unit 6: Guanyin 观音 told the Jade Emperor 玉皇大帝 about this matter, and the Jade Emperor granted the third daughter the title of “Ma-Ming silkworm room 马鸣蚕室”.

Similar ballads are known from all over the sericulture area of Zhejiang Province. The whole story is similar to the “silkworm horse” story, but the location of the story and the process of the daughter becoming a goddess have become more specific due to the infiltration of Taoist thought. The change of the vower from a daughter to a mother is in closer accordance with the marriage custom of “the order of parents 父母之命” in ancient Chinese society. This custom is influenced by Confucianism and based on the patriarchal clan and family system. In addition, the surname of the daughter has been implemented in ballads, which has increased the credibility and intimacy of the silkworm deity. Finally, it has been implemented into the folk worship custom, and the statue of the silkworm deity has been molded to pray for the smooth development of the silkworm.

The wide spread of the worship of Ma-Tou-Niang in areas of sericulture in ancient China indicated that sericulture had become the main industry in the agricultural economic structure, and Ma-Tou-Niang had also become a collective belief of sericulturists and the patron saint of sericulture. The construction of the silkworm temple, the spread of ballads, and the popularity of “Can hua play” gradually made the silkworm deity more lifelike in the process of combining folk beliefs with literary and artistic activities. Sericulturists’ belief in the silkworm deity also changed from a decentralized behavior of each family to a collective behavior. The periodic worship of the silkworm deity strengthened sericulturists’ memory of Ma-Tou-Niang, thus making Ma-Tou-Niang a common belief. Indeed, it is the silkworm deity with the most complete folk preservation, the most widespread circulation, and the highest recognition from sericulturists. This reflects the utilitarian view of folk religion that a sericulturist has. In addition, in the process of spreading the myth and folklore of Ma-Tou-Niang, Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism integrated it. This was an inevitable change in folk religion, under the influence of the general trend of the integration of the three religions after the Mid-Tang Dynasty (766–835).

4. The “Xian-Can” Deity Based on the Founder of the Trade

The trade founder is often regarded as the original creator of a trade or the protector of trade production. The trade founder is the embodiment of the functional god, and the reflection of the social division of labor in folk religion. Before the emergence of the founder god of the trade, sericulturists worshipped a deified silkworm, and the Ma-Tou-Niang was born after humanizing the silkworm through myth. With the development of the handicraft industry and the continuous maturity of sericulture, sericulturists created the trade founder god based on a human prototype—that is, the founder of sericulture “Xian-Can 先蚕”—along with the spread of the legend of Xian-Can educating people about sericulture. In medieval China, there were three silkworm deities known as the ancestor gods of sericulture, namely “Yuan-Yu woman 菀窳妇人”, “Princess Yu 寓氏公主”, and “Lei Zu”.

The earliest record of the founder of sericulture appeared in the Western Han Dynasty (202 BCE–8 CE):

Can Jing 蚕经 records that “Xi-Ling-Shi persuaded people to raise silkworms, and from then on, there was a ceremony for the empress to sacrifice the Xian-Can” (

Xu 2020, p. 1082). Zheng Xuan, a Confucian scholar of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 CE), believed that “Xi-Ling-Shi, the concubine of the Yellow Emperor 黄帝, created sericulture” (

Sun 1989, p. 431).

Shi Ji 史记 clearly points out that “Xi-Ling-Shi” is “Lei-Zu” (

Sima 1982, p. 10). Although the ancient books of the Han Dynasty clearly recorded that Lei-Zu was the founder of sericulture, it was not officially recognized as the “Xian-Can” of court sacrifice. At that time, the officially recognized “Xian-Can” was recorded as “Yuan-Yu woman” and “Princess Yu” (

Sun 1990, p. 45). In medieval China, “woman” refers to the spouse of a man of the “scholar” class. Since “scholar” is a general name for intellectuals in the ruling class and the lowest level of nobility, the “woman” status has just reached the threshold of the ruling class. “Princess” is one of the titles of female descendants of Chinese emperors and princes, and is an honorific title for women who have made important contributions. It belongs to a high-level, noble group. Therefore, although “Yuan-Yu Woman” and “Princess Yu” are both silkworm deities, there are obvious differences in their status, which are based on the institutionalization of Confucianism.

By the Jin Dynasty (266–420 CE), the two silkworm deities had merged into one, so there was a single silkworm deity named “Princess Yu of Yuan-Yu woman” in the illustration of the “silkworm deity” in

Nongshu 农书 of the Yuan Dynasty (

Figure 8a). According to

Sou Shen Ji 搜神记, “Yuan-Yu Woman” is the founder of the silk industry, and “Princess Yu” is her honorific (

Gan 2019, p. 335). Although “Yuan-Yu woman” was a low-level aristocrat, she was promoted to a higher level because of her invention of sericulture, and so was honored as a “princess”. The status of “Xian-Can” changed from the wife of a scholar to a princess, thus her being included in the order of the ruling class. This indicated the promotion of the status of the silkworm deity under the influence of the feudal social hierarchy. Only by raising the status of “Xian-Can” as a member of the royal family can she be worthy of the royal sacrificial rites, which is an example of the feudal hierarchy of Confucianism. Therefore, although “Yuan-Yu Women” and “Princess Yu” were no longer the “Xian-Can” to be offered official sacrifices in the Jin Dynasty, as the object of royal sacrifices, they still needed to be identified as princesses, which was in line with the norms of social etiquette based on Confucianism.

After the Eastern Han Dynasty, with the promotion of Confucianism, the system of ethics was further standardized. The identity of a “princess” was no longer sufficient for the silkworm deity to be worshiped by the empress. Lei-Zu, who was the wife of the Yellow Emperor, replaced “Yuan-Yu woman” as the “Xian-Can” recognized by both the court and the folk. The Northern Zhou Dynasty (557–581 CE) was an important period when the status of the “Xian-Can” changed.

Sui Shu 隋书 recorded that the empress led noblewomen to worship the Xian-Can “Xi-Ling-Shi 西陵氏”, which was the ritual system of the Northern Zhou Dynasty (

Wei and Linghu 1973, p. 145). In medieval China, “Shi 氏” is the name given to married women. “Xi-Ling-Shi” is a married woman whose father’s surname is “Xi-Ling”. The relevant mention of “Xi-Ling-Shi” in the

Shi Ji 史记 is that “the Yellow Emperor lived on the hill of Xuanyuan and married the daughter of Xi-Ling as Lei-Zu. Lei-Zu was the imperial concubine of the Yellow Emperor” (

Sima 1982, p. 10). Lei-Zu belongs to the Xi-Ling family. The Xi-Ling family lives in Xiping, Henan. It is said that this area is where Nu-Wa and Fuxi lived for generations, so it is regarded as the descendant of Nu-Wa and has a special status and reputation. Therefore, Lei-Zu’s identity before marriage is as the daughter of a powerful family. The Yellow Emperor has been regarded as the founder of Chinese civilization since ancient times, and his status is as the ancestor of the Chinese nation. After Lei-Zu married the Yellow Emperor, she had the same status as, or higher than, the empress, so she was qualified to be the silkworm deity that the empress personally worshiped.

In the Tang Dynasty, “Yuan-Yu Woman” and “Princess Yu “were divided into two again, and formed a silkworm deity in combination with Lei Zu. According to the inscription, “the Lei-Zu Holy Land” in the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), “Yuan-Yu Woman” and “Princess Yu “became the three holy statues of “Lei-Zu Temple” together with Lei-Zu (

Wang 1993, p. 40). However, from the perspective of the holy land named after Lei-Zu, Lei-Zu has become the orthodox silkworm deity. The combined images of the three silkworm deities appeared in the illustrations of “Xi-Ling-Shi 西陵氏” in

Nong Shu 农书 “

Figure 8b”; Xi-Ling-Shi is dressed in palace clothes, holding a Wat Board in her hand, followed by Yuan-Yu Woman and Princess Yu, one dragging a disc and the other carrying a bamboo basket with cocoons inside.

Lei-Zu’s contribution to sericulture is recorded in ancient books as “Lei-Zu, the daughter of Xi-Ling’s family, was the imperial concubine of the Yellow Emperor. She first taught the people to raise silkworms, reel silk, and make clothes, so that no one was frozen or sick. Later, people worshipped her as Xian-Can” (

Wu 1960, p. 13). Lei Zu became the official orthodox silkworm deity due to the invention and promotion of mulberry planting and silkworm-rearing technology, and then gained widespread recognition among the people through the cultivation of the ruling class. The official recognition of the function of Lei-Zu shows that the ruling class tried to bring the worship of silkworm deity under the remit of social education, which goes beyond the utilitarian mentality of sericulturists’ worship of the silkworm deity. The ruling class attached importance to the role of etiquette in educating the people, which is an important part of Confucian political ideology. The ruling class popularized Lei-Zu as the “Xian-Can” to the people, which standardized the silkworm deity sacrifice system along with social norms, so as to further promote silkworm affairs in folk production activities, and make the edification behavior full of political significance.

Thus, it can be seen that the worship of Lei-Zu and Qing-Yi God was a spiritual belief accompanied by a social division of labor in medieval China. It was also a belief that the ruling class and folk sericulturists hoped would meet the needs of social education and attract the help of the spiritual power of the patriarch of the silk industry. The development of sericulture in silkworm-breeding areas has strengthened the long-standing position of sericulture, which is also the inevitable result of the secularization of religious beliefs.

5. Worship of Derivative Godhood

“Zi-Gu 紫姑” and “Shui-Cao-Ma-Ming-Wang 水草马明王” are not the main deities in charge of sericulture, but they are more common silkworm deities worshipped by sericulturists. In the folk tradition, Zi-Gu is the Toilet Goddess, Shui-Cao-Ma-Ming-Wang is the Horse God, and the silkworm deity is their derived godhood.

The relevant records of Zi-Gu containing the godhood of the silkworm deity in the literature were first seen in the Southern Song Dynasty (420–479 CE). In

Yi Yuan 异苑, it is recorded that “Zi-Gu can predict whether the sericulture will go well this year” (

Li 1961, p. 2327). It is clearly recorded in the

Jing Chu Sui Shi Ji 荆楚岁时记 of the Liang Dynasty (502–557 CE) that sericulturists asked Zi-Gu on the night of January 15 of the lunar calendar to predict future sericulture (

Zong 2018, p. 21). Zi-Gu is also known as “San-Gu 三姑” in folk religion. The custom of sericulturists in Zhejiang petitioning “San-Gu” during the Lantern Festival has continued to today (

Yu 1993, pp. 14, 120–24). This custom shows the evolution of Zi-Gu divination in sericulture.

The folk myth about the origin of the Zi-Gu Goddess has experienced several evolutions. The early plot of the story is relatively simple. According to the records of

Yi Yuan 异苑, “the wife was jealous of the concubine and often asked her to clean the toilet. Later, she killed the concubine in the toilet on the night of January 15 of the lunar calendar. People take the day when the concubine died as the day of worship, and worship Zi-Gu goddess beside the toilet or pigsty” (

Li 1961, p. 2327). The myth of “Zi-Gu Goddess” (

Yi 2019, p. 144) was further concretized in

San Jiao Yuan Liu Sou Shen Da Quan 三教源流搜神大全. The storyline units are as follows:

Unit 1: He Mei, a woman in Laiyang 莱阳, has been literate since childhood.

Unit 2: In 687, He Mei became the concubine of Li Jing, the governor of Shouyang 寿阳.

Unit 3: Li Jing’s wife was jealous of He Mei and killed her in the toilet on the night of the 15th day of the lunar calendar.

The illustration of the “Purple goddess” (

Figure 9a) in

Recherches sur les supersessions en China vividly depicts how, on the full moon, in a narrow outhouse in the courtyard, a woman is sitting on a toilet, with a candle beside her feet. Outside the toilet, another woman holds two sticks, which is the scene in the story where the wife is about to kill the concubine. Since Zi-Gu died on the night of the Lantern Festival, the folk custom of inviting Zi-Gu during the Lantern Festival began. “San-Gu” is the nickname of Zi-Gu as the silkworm deity. The image was first seen in the illustrations of “ Silkworm deity” (

Figure 9b) in

Nong shu 农书 (1314), which is the image of a palace dressed woman.

Divination is a ritual activity used to predict fortune or misfortune in medieval China, usually closely related to religion. The agricultural economy dominated the vast area south of the Great Wall of China in the Middle Ages, and sericulture belongs to this branch of agriculture. The relationship between divination and agriculture can be traced back to the Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE). It was developed on the basis of primitive witchcraft, combined with ancient phenology and a traditional view of nature. Sericulturists inviting Zi-Gu is usually a way of predicting whether the silkworm harvest will be good or bad. The method used is “Gan Zhi Ji Nian 干支纪年” (

Zhai 2013, p. 410;

Qian 2016, p. 216;

Wang 1956, p. 85). The divination results are as follows:

“Four Meng year 孟年, Yin 寅, Shen 申, Si 巳, Hai 亥, Da-Gu 大姑 hold silkworm, mulberry leaves are cheap.

Four Zhong year 仲年, Zi 子, Wu 午, Mao 卯, you 酉, Er-Gu 二姑 hold silkworm, mulberry leaves are expensive.

Four Ji year 季年, Chen 辰, Xu 戌, Chou 丑, Wei 未, San-Gu 三姑 hold silkworm, mulberry leaves are sometimes expensive and sometimes cheap”.

In Confucianism, “Meng”, “Zhong”, and “Ji” represent not only the eldest, the second, and the youngest, but also the general rule that things develop from the beginning to the peak and then to the end. In medieval China, “Gu” usually refers to women. “Da-Gu”, “Er-Gu”, and “San-Gu” usually refer to the ranking of three sisters in the family, echoing “Meng”, “Zhong”, and “Ji”. The “Four Meng Years”, “Four Zhong Years”, and “Four Ji Years” symbolize the development law of the silkworm industry in ancient China, with a small round every 3 years and a large round every 12 years. The price of mulberry leaves is closely related to silkworm rearing. The price of mulberry leaves is cheap, which means that there are fewer silkworms but more mulberry leaves, and the final harvest of silk is less. The price of mulberry leaves is expensive, which means that there are more silkworms but fewer mulberry leaves, and the final harvest of silk is greater.

This means that the first year of each small harvest indicates the beginning: “Da-Gu” is responsible for sericulture, and the silk harvest is poor. The second year indicates the peak: “Er-Gu” is responsible for sericulture, and the silk harvest is good. The third year indicates the end: “San-Gu” is responsible for sericulture, and the silk harvest can be good or bad, and is difficult to predict. Although it is scientific to use the law of development of silkworm affairs for divination, it has religious significance when combined with the different years of the three sister silkworm deities. Due to the need for divination, the image of San-Gu has gradually evolved into the image of three goddesses in the same frame under the influence of Da-Gu, Er-Gu, and San-Gu in the oracle (

Figure 10). The woman in the middle holds a silk winding frame, which is full of silk threads, and two girls on both sides hold bamboo baskets full of silkworms and mulberry leaves.

Shui-Cao-Ma-Ming-Wang 水草马明王 is also known as “Ma-Zu 马祖”, “Shui Cao Da Wang 水草大王”, and “Ma Wang Ye 马王爷”, which are the protective god of horses and the founder of the livestock trade. In ancient China, horses can be used for war, travel, transportation, and farming, so there has been a system of offering sacrifices to Ma-Zu in spring. Ma-Zu first referred to the Tiansi constellation, which is one of the typical objects of celestial worship in Chinese folk religion. Scholars in the Han Dynasty believed that “silkworms and horses share the same spirit” (

Sun 2013, p. 2377)—that is, the silkworm and the horse are the same body. At the same time, the constellation at the time of silkworm hatching is also Tiansi 天驷. Therefore, in the illustration of “Silkworm deity” in

Nong shu 农书, Tiansi constellation is also one of the silkworm deities, and the silkworm deity has also become the derived divinity of the Horse God. The folk worship of Shui-Cao-Ma-Ming-Wang is the personification of the Horse God, which was first seen in the “Shui Cao Da Wang 水草大王” (

Tao 2019, p. 169) in

Yin Hua Lu 因话录 of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279 CE).

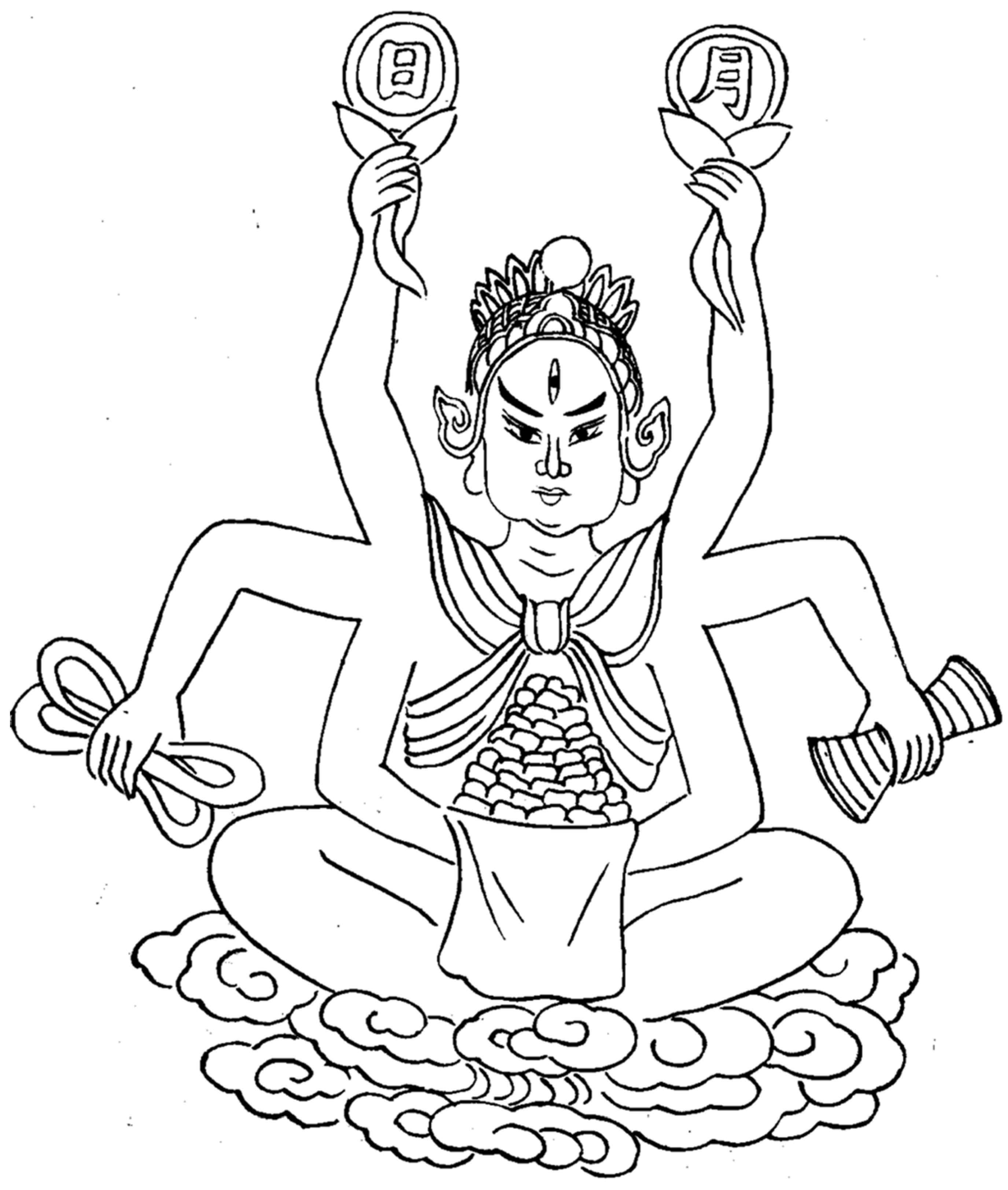

The name of Shui-Cao-Ma-Ming-Wang is influenced by Buddhist culture. The Sanskrit of “Ming Wang 明王” is Vidyā-rājā; it is regarded as “God” in the folk tradition, and Ma-Ming-Wang is the Horse God. The prefix “Shui Cao 水草” refers to livestock protected by the Horse God that feed on water and grass. The folk image of Shui-Cao-Ma-Ming-Wang is generally four arms and three eyes (

Figure 11a), with the third eye a vertical one in the middle of his forehead. The image of “Ma-Ming-Wang” with eight arms and three sides appeared in “A picture of Farming and Weaving” of the Yuan Dynasty (

Figure 11b), in which three pairs of arms extend outward, holding weapons such as double swords and bows and arrows from top to bottom, and the hands of another pair of arms are placed palms together at the chest.

The “Can Hua Wu Sheng 蚕花五圣” (

Figure 12) worshipped by sericulturists in Haining 海宁, Zhejiang is a male silkworm deity with three eyes and six arms, which evolved from Shui-Cao-Ma-Ming-Wang. The first pair of hands are held up, one holding the “sun”, one holding the “Moon”; the second pair of hands are drooping, one holding a bunch of silks, one holding a silk winding board; and the third pair of hands are holding a silk with cocoons piled on it. Shui-Cao-Ma-Ming-Wang transformed his weapons into silk and silk processing tools, and turned them into the image of “Can Hua Wu Sheng”, which completed the transformation from a derived divinity to the main divinity, reflecting the practical function of silkworm deity worship under the influence of the utilitarian mentality of folk sericulturists.

To sum up, before becoming a God, Zi-Gu was a concubine with low status and a miserable fate. Because she often cleaned the toilet and died in the toilet, Zi-Gu’s main divinity was as the Toilet Goddess. However, because she could divine sericulture, she derived a new divinity. Before Shui-Cao-Ma-Ming-Wang became a god, he was the official in charge of horses in the imperial court. The main divinity was the Horse God, which derived a new divinity because of the theory of silkworm and horse homology. With the further demand of silkworm farmers for a derived divinity, the conversion of the priest was completed through the transformation of the image. In medieval China, sericulturists’ worship of Zi-Gu Goddess and Shui-Cao-Ma-Ming-Wang reflects the compatibility of folk gods in a practical worship mentality, and, together with many silkworm deities, it forms a pluralistic and coexisting belief system.

6. Conclusions

“Folk religion” involves belief in the deities, ancestor spirits, and ghosts of a region or family. Seasonal celebrations and rituals, the ritual organization of Temple sacrifices, annual sacrifices, and organizations were based around blood families and regional temples (

Wang 1997, p. 156). In medieval China, the ruling class and folk silkworm farmers created many vivid silkworm deities in order to pray for a good harvest and success in sericulture activities.

The worship of the silkworm deity in medieval China evolved from the worship of primitive constellations and animal gods. The original silkworm deities were the Tiansi constellation and the silkworm itself, which was the result of primitive human symbolization of natural forces. With the establishment of the country, the division of classes, and the formation of the division of labor, the concept of the worship of the silkworm deity began to change. The natural factors in the image of the silkworm deity gradually weakened, and the trend of personalization gradually increased. The woman with the silk-spinning ability of the silkworm and the horse skin-wrapped Ma-Tou-Niang are the products of the transition from a natural form to a human form. The birth of “Yuan-Yu woman” and “Princess Yu “in the Eastern Han Dynasty completed the evolution of the personification of the silkworm deity, and gave the silkworm deity its name and identity. The emergence of “Lei-Zu” in the Northern Zhou Dynasty officially incorporated the silkworm deity into the official worship system, identifying the silkworm deity as the wife of the Yellow Emperor, who was in charge of silk production. Compared with the Ma-Tou-Niang with its absurd mythological background, Lei-Zu’s achievements in educating the people in sericulture and silk-reeling reflect the official interpretation of the rationalization of the silkworm deity and the intention of giving play to the function of folk education through the dissemination of Lei-Zu’s belief.

The difference between the folk silkworm deity and the court silkworm deity is that the court exclusively worshiped Lei-Zu, and had a complete set of sacrificial system that has continued through the ages. The folk silkworm deity started with myths and legends, and developed a number of strands, each of which has been widely recognized regionally. Sericulturists in the same region can worship multiple silkworm deities at the same time, and the same silkworm deity also has several duties. Almost every silkworm deity has more or less integrated the “great tradition” or “elite religion” represented by Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. Due to the influence of the three religions and polytheism, the folk sacrificial customs of the silkworm deity are diverse. In addition to the villages where the Xian-Can temple and the silkworm deity temple were built separately, the sericulturist can offer sacrifices at home, in the kinship unit of the family, and the silkworm temple in some areas is attached to the Taoist temple (

Xiao 2021, pp. 94–103). This diversity reflects the intermingling of folk religious forms in medieval China, making it impossible for us to classify them by a unified standard. However, as a small branch of religious art, the image of the silkworm deity in various medieval artworks has no doubt been used to serve the ritual activities of silk practitioners.

In fact, although the worship of the silkworm deity includes many different images of the silkworm deity, there is actually a common order to the conceptual and practical aspects (

Liu 2009, pp. 1–11). The evolution of the silkworm deity in medieval China was a religious consciousness with a polytheistic tendency, promoted by Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism under the influence of the continuous integration of medieval Chinese society and folk religion. It could be part of an official sacrificial ceremony, or part of a private community or family sacrificial ceremony. It was a cultural resource shared by sericulturists. Among silkworm deities, women accounted for the majority, in line with the tradition of men farming and women weaving in ancient Chinese agricultural society. The tradition of depicting the silkworm deity in paintings, illustrations of ancient books, woodblock prints, and portrait stones continued from the Han Dynasty to the Yuan Dynasty. We have, therefore, been able to track the evolutionary history of the silkworm deity image alongside the history of silkworm deity worship in the Middle Ages.