Jewish–Christian Interaction in Ethiopia as Reflected in Sacred Geography: Expressing Affinity with Jerusalem and the Holy Land and Comemorating the Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic Wars

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Sacred Geography and Religious Architecture as a Realm of Interreligious Discourse in Ethiopia

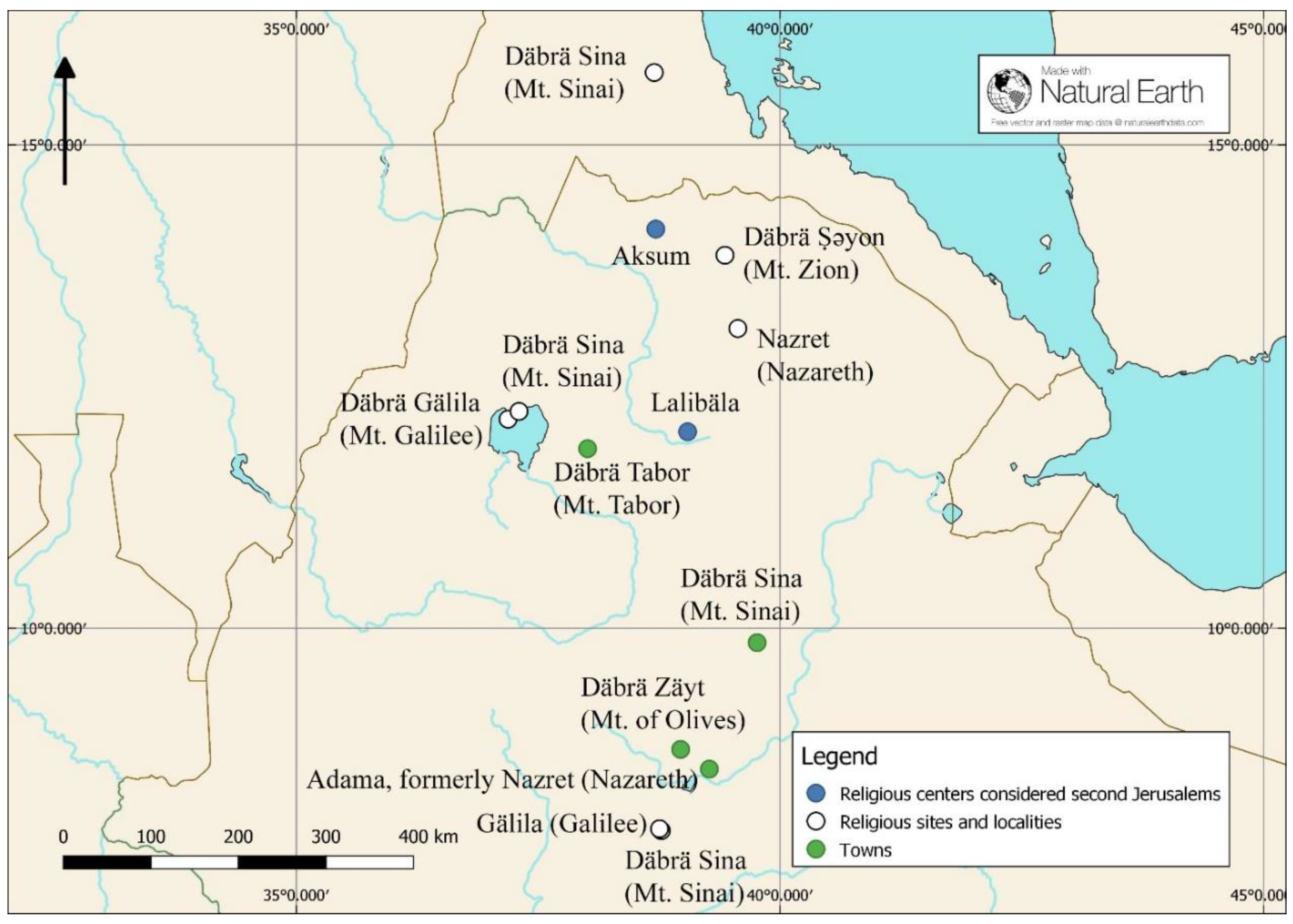

2. Israelite Heritage in Solomonic Ethiopia

3. The Holy Land and Second Jerusalems in Ethiopia

And Azaryas said: ‘bring forth the Jubilee, and we shall go to Zion [the Ark of the Covenant] and there we shall renew the reign of our lord David.’ And he took a horn full of royal anointment oil, and anointed him […] And so the reign of David, son of Solomon, king of Israel was renewed, in the city of government, on Mount Makǝda,9 in the House of Zion.10

I blessed this place and from now onwards let it be a holy place as Mount Tabor, the place of my transfiguration, as Golgotha, the place of my crucifixion, and as Jerusalem the land of my mother […] If a man abides in it, or undertakes pilgrimage to it, it is as if he went to my Sepulcher in Jerusalem.15

Here we shall write the account of the insolence of Rädaʾi [the Betä Ǝsraʾel leader] […] He called the mountains of his towns by the names of the mountains of Israel. One he called Mount Sinai and a second Mount Tabor and there are others, the names of which we have not mentioned. How evil is the pride of that Jew who likened his mountains to the mountains of the Land of Israel, on which God descended and revealed upon them the mysteries of his kingdom.26

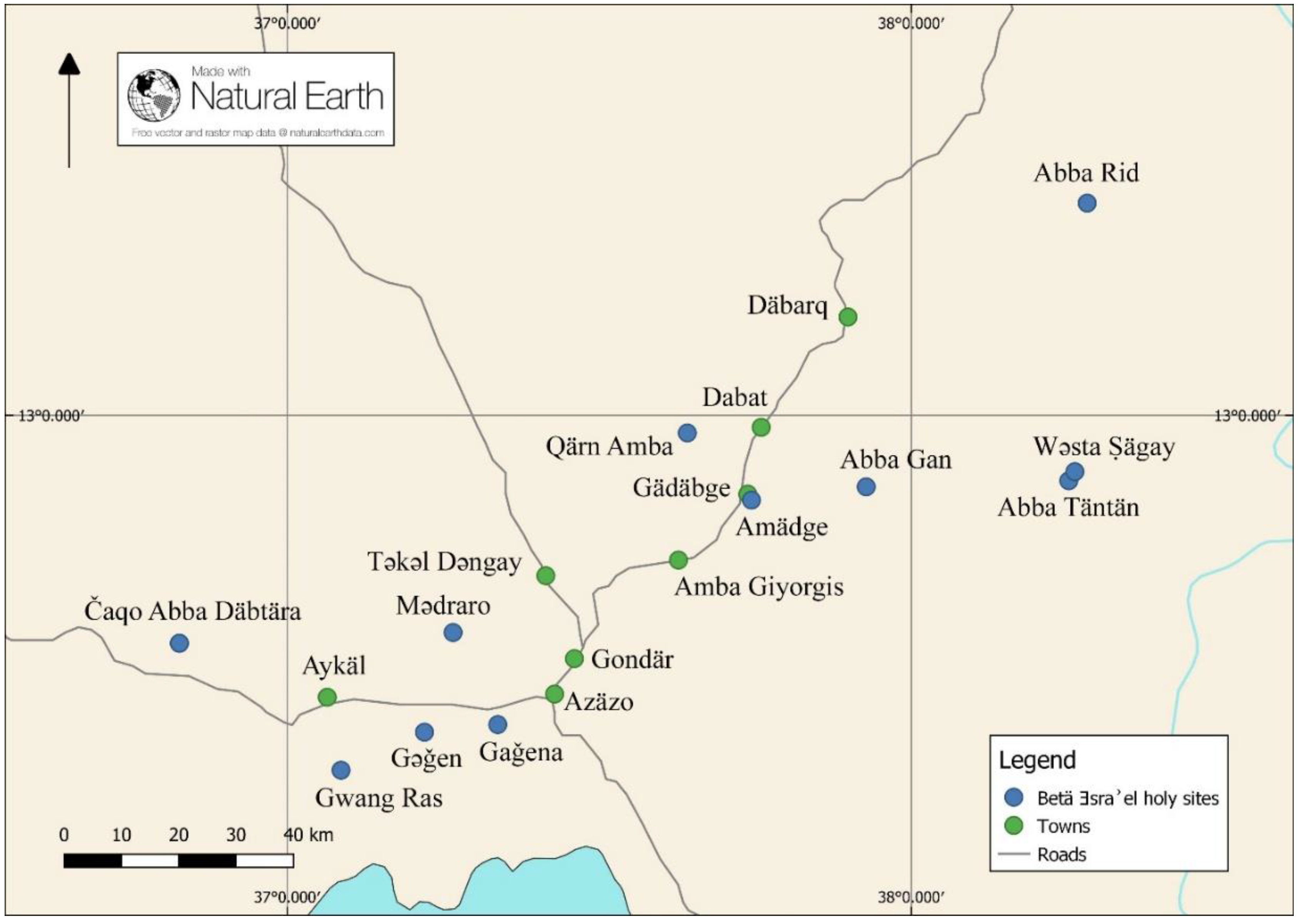

4. Affinity with Jerusalem in Betä Ǝsraʾel Holy Sites

4.1. Betä Ǝsraʾel Holy Sites

4.2. Səmen Mənaṭa

4.3. Abba Gan (Gäntaba)

4.4. Gwang Ras

4.5. Č̣aqo Abba Däbtära

5. The Temple as Inspiration in Prayer Houses

6. Commemoration of the Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic Wars in Sacred Geography

6.1. The Holy Springs of Wəsta Ṣägay

6.2. The Church of Yəsḥaq Däbr

7. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In this study, the national church of Ethiopia, which at present is commonly referred to as the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwaḥədo Church, will be referred to as the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. |

| 2 | The transcription system of the Encyclopedia Aethiopica will be used here for terms in Ethiopic languages: Geʿez, Amharic, and Tǝgrǝñña. For Ethiopian names, the English spelling preferred by the individual in question will be used. In cases where this spelling is not known, the transcription of the name’s spelling in Amharic or Tǝgrǝñña will appear. |

| 3 | Notable among the works examining Betä Ǝsraʾel identity discourse and its interplay with Ethiopian Orthodox identity discourse are the works of Shelemay (1989); Kaplan (1992); Quirin (1992); Abbink (1990); and Salamon (1999). Scholarship on Ethiopian Orthodox religious architecture and sacred geography is extensive. Key works include the studies of Phillipson (2009); Heldman (1992); Lepage and Mercier (2005); and Fritsch and Gervers (2007). |

| 4 | At present, no comprehensive study of Betä Ǝsraʾel prayer house structures exist, though the liturgy conducted within them has been studied extensively (Shelemay 1989; Ziv 2017), and a general overview of such structures appears in a few studies (Flad 1869, pp. 42–44; Leslau 1951, pp. xxi–xxiii; Shelemay 1989, pp. 71–78). As part of the present author’s research on Betä Ǝsraʾel monastic material culture (a central element of which was an archaeological survey in Ethiopia), a preliminary typology of Betä Ǝsraʾel prayer houses was defined, and the remains of several prayer houses were surveyed (Kribus 2022). Prior to the present author’s research, only two articles examining Betä Ǝsraʾel holy sites in detail had been published: Ben-Dor’s (1985a) study of Betä Ǝsraʾel holy sites, and Leslau’s (1974) publication of Taamrat Emmanuel’s notes on Betä Ǝsraʾel monastic holy men and holy places, both primarily based on interviews with members of the Betä Ǝsraʾel community. The survey of the dwelling places of the Betä Ǝsraʾel mäloksewočč (monastic high priests) was the first to pinpoint the location of Betä Ǝsraʾel holy sites with precision and document their remains in situ. Four Betä Ǝsraʾel holy sites were visited in its course, and five additional holy sites viewed from a distance. The archaeological survey of the dwelling places of the Betä Ǝsraʾel mäloksewočč was led by the present author, together with Sophia Dege-Müller and Verena Krebs, and carried out under the auspices of the ERC project “Jews and Christians in the East: Strategies of Interaction between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean” (JewsEast) at the Center for Religious Studies of the Ruhr University, Bochum, and the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. |

| 5 | For a study on the interreligious dialogue embodied in Betä Ǝsraʾel, Ethiopian Orthodox, and Kǝmant sites dedicated to a holy man by the name of Yared in the Sǝmen Mountains, see Dege-Müller and Kribus (2021). The present author has recently submitted an article comparing general features of Betä Ǝsraʾel and Ethiopian Orthodox prayer house architecture and concepts associated with these features (Kribus forthcoming a). This article, while dealing with the concept of the prayer house’s affiliation with the Jerusalem Temple (a concept discussed in the present article as well), does not examine the sacred geography of the two communities and the affiliation between their holy sites, Jerusalem and the Holy Land—issues that are at the heart of the present article. |

| 6 | |

| 7 | This is a rendering of the Arabic “Ibn al-Ḥakīm,” “son of the wise man” (Fiaccadori 2007). |

| 8 | The Kingdom of Aksum emerged circa the first century BCE/first century CE and gradually expanded to encompass the present-day region of Tǝgray, the highlands of Eritrea, and the adjacent Red Sea coast. It was involved in the international Red Sea trade and extended its influence into the Nile Valley and South Arabia. In the fourth century, the king and elite converted to Christianity. By the sixth century, Christianity had become established as the dominant religion in the kingdom. The kingdom’s decline was a gradual process, which took place during the seventh/eighth century CE (Munro-Hay 1991; Phillipson 2012). |

| 9 | The hill towering above the town of Aksum to the west is known today as Betä Giyorgis (House of St. George), named after a church located upon it. Local tradition identifies it as Däbrä Makǝda, the Mountain of the Queen of Sheba, though the chronology of this tradition is unknown. This raises the question of whether this is the locality referred to in this passage of the Kǝbrä Nägäśt. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | The main church in the town of Aksum was destroyed or damaged, and subsequently rebuilt or renovated, several times in its history. A large church (perhaps the original, Aksumite-period structure) is attested to have existed in the 1520s and was destroyed during the temporary Islamic conquest of the northern Ethiopian highlands (1529–1543). A church was then built on the site by the Solomonic monarch Śärṣä Dǝngǝl (r. 1563–1597), burnt in a raid in 1611, and then renovated by the Solomonic monarch Fasilädäs (r. 1632–1667). Additional renovations were carried out by the Solomonic monarch Iyasu II (r. 1730–1755). A modern church structure, adjacent to the previous one, as well as the Chapel of Ark of the Covenant, were built during the reign of Haile Selassie I (r. 1930–1974). For an overview of the history of Maryam Ṣəyon Church with references to relevant sources, see Munro-Hay (2003). |

| 12 | The precise chronology of this dedication is unknown. It is first attested in its complete form in a later copy of a fifteenth-century document. Based on a hadith attributed to the ninth century and mentioning the dedication of an Aksumite church to Mary, and the similarity between the Aksumite Cathedral’s plan to that of the Byzantine Church of Holy Zion on Mt. Zion in Jerusalem, it has been suggested that both the dedication to Mary and an association with Zion may date back to Aksumite times (Heldman 1992, pp. 227–28; Munro-Hay 2003, 2005, pp. 165–70). It should be noted that an association of Mary with the Ark of the Covenant is a common one in the Christian tradition, since the Ark, as a container for the tablets embodying the Old Testament, is equated with Mary, whose pregnancy with Jesus is understood as her carrying within her the New Testament (see, for example, Munro-Hay 2005, pp. 29–31, 36). |

| 13 | |

| 14 | Suggested datings of this dynasty’s rise to power range from the tenth to the twelfth century. For an overview on this issue, see Phillipson (2012, p. 228). |

| 15 | This section of the text and the translation is provided by Sergew Hable Sellassie (1972, p. 276). The Gädlä Lalibäla (on which the Zena Lalibäla is based) is dated to the end of the fourteenth or the beginning of the fifteenth century (Derat 2007). |

| 16 | This town, east of Lake Ṭana, was founded in the first decade of the nineteenth century and served as the capital of the Solomonic emperor Tewodros II (1855–1868) (Pankhurst 2005). |

| 17 | This town, in the province of Šäwa, was founded in 1936, however, the place-name, in the general area, predates its foundation (Omer 2005). |

| 18 | This town, south-east of Addis Abäba, was established in the late nineteenth century (Mekete Belachew and Gascon 2005). |

| 19 | Nazret is the name of a locality featuring an archaeological site in eastern Tǝgray, in which are the remains of a structure with Aksumite features, used, in later times, as a church (Henze 2007). |

| 20 | This monastery, in the Gärʿalta region of Tǝgray, seems to have been established at the end of the fourteenth century (Lusini 2005a). |

| 21 | This monastery, on an island bearing this name in Lake Ṭana, was founded in the fourteenth century (Bosc-Tiessé 2005). |

| 22 | The monastery of Däbrä Sina in the Sänḥit region of present-day Eritrea traditionally dates back to Aksumite times and played a role in Ethiopian Orthodox theological discourse in the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries (Lusini 2005b). The monastery of Däbrä Sina on the northern shore of Lake Ṭana, near Gorgora, traditionally dates to the reign of the Solomonic monarch ʿAmdä Ṣǝyon (1314–1344). Its present-day church is dated to the seventeenth century (Balicka-Witakowska 2005). |

| 23 | This island is home to an Ethiopian Orthodox community which predated the sixteenth–seventeenth centuries that remains to this day (Henze 2005a). |

| 24 | This island was inhabited until the 1970s. Its church was traditionally founded in the thirteenth century (Henze 2005b). |

| 25 | Following its foundation in 1270, the Solomonic kingdom, originally centered in the northeastern Ethiopian Highlands, gradually expanded into the northwestern Ethiopian Highlands and consolidated its rule there, a process that was occasionally accompanied by military campaigns. Several campaigns against autonomous factions of the Betä Ǝsraʾel took place between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries (Kaplan 1992, pp. 79–96; Quirin 1992, pp. 40–88). The chronical of Śärṣä Dǝngǝl contains some of the most detailed descriptions of such campaigns. |

| 26 | Conti Rossini (1907, p. 99). My translation. |

| 27 | Both Christian missionaries and Rabbinical Jewish emissaries attempted to bring about changes in Betä Ǝsraʾel religious practices. One method used was to argue that specific Betä Ǝsraʾel practices were not in accordance with (the missionaries’ or emissaries’ interpretation of) biblical decree. It was common for individuals with a Rabbinical background to be critical of Betä Ǝsraʾel religious practices differing from Rabbinical ones. This, as well as the decades of struggle the community had to undergo in order to be recognized as Jews by the State of Israel and thus, to be able to make Aliyah (immigrate) there, has often placed the community in the position of needing to respond to criticism. Accordingly, some modern narrations of oral traditions regarding the community’s past incorporate within them such responses, or employ concepts derived from Rabbinical discourse. For instance, in response to a question, often posed, regarding why Hebrew was not used by the Betä Ǝsraʾel, a common response is that the community had Hebrew texts in the past, but these were lost or taken by the Christians in the course of the wars with the Solomonic Kingdom (for specific examples of such responses, see Wovite Worku Mengisto and Kribus forthcoming). |

| 28 | Longing for Jerusalem is, for example, a central theme in numerous accounts provided and literary works written by members of the community (Qes Ḥädanä Təkuyä 2011, p. 122; Waldman 2018, pp. 290, 292, 295–96). |

| 29 | |

| 30 | The mäloksewočč (singular: mälokse) served as the community’s high priesthood. They, unlike the lay priesthood (the qesočč), observed severe purity laws that necessitated physical separation not only from Gentiles, but also from the lay community. In scholarly and popular literature, the mäloksewočč are often referred to as monks. However, since, in this case, we are dealing with a Betä Ǝsraʾel institution with unique features, which played a key role in safeguarding the Betä Ǝsraʾel religious tradition and combating Christian missionary efforts, the Betä Ǝsraʾel community prefers the usage of its own terminology when referring to this institution. |

| 31 | Səmen Mənaṭa, as well as the holy sites of Abba Gan and Gwang Ras which will be described below, were visited in the course of the present author’s survey of the dwelling places of the Betä Ǝsraʾel mäloksewočč. For a description of this site and the holy sites in its vicinity, see Kribus (2022, pp. 93–116). |

| 32 | The letters “n” and “l” are often interchangeable in colloquial Amharic. |

| 33 | In accordance with the norms of ethnographic research, I have decided to maintain the anonymity of informants in this publication. When referring to publications in which the names of informants are provided, the name of the respective informant will also be provided here. |

| 34 | Interview transcript, Institute of Contemporary Jewry, project no. 182, folder no. 28. |

| 35 | For an overview of this holy man and the sites associated with him, see (Ben-Dor 1985a, pp. 41–45; Kribus 2022, pp. 12–18, 87–90, 167–77). |

| 36 | The offering of sacrifices by the priesthood in accordance to biblical decree was an integral part of Betä Ǝsraʾel religious practices until the twentieth century. See, for example, (Flad 1869, pp. 52–54; Leslau 1951, pp. xxvi–xxvii; Lifchitz 1939). |

| 37 | Fire descending from the heavens and consuming the sacrifices offered by the community is a common motif in traditions relating to Betä Ǝsraʾel holy sites and holy men. See (Ben-Dor 1985a, pp. 44–46; Kribus 2022, pp. 146, 175, 179–81, 215). |

| 38 | For a reference to the offering of incense in Betä Ǝsraʾel liturgy, see (Flad 1869, pp. 6, 44). |

| 39 | Concentric churches of this type sometimes feature an octagonal rather than circular exterior. |

| 40 | For a detailed overview of Ethiopian Orthodox church architecture and its development over time, see (Heldman 1992; Lepage and Mercier 2005; Phillipson 2009). |

| 41 | For a detailed examination of this prayer house type and suggestions regarding its development, see (Fritsch 2018; di Salvo 1999). It should be noted that a second Ethiopian church type with an enclosed quadrangular sanctuary also exists (Heldman 2003, pp. 738–39; di Salvo 1999, pp. 73–76). This second type is rectangular and oriented east–west. |

| 42 | See, for example, Perruchon (1893, pp. 126–27). Churches are commonly referred to as Betä Kərstiyan, i.e., House of Christian (worship). |

| 43 | Munro-Hay (2005, pp. 27–51) argues that the Ethiopian tabot is based on the Coptic altar slab, known as maqṭaʿ, which serves the same purpose as a tabot but did not acquire the tabot’s symbolism or sanctity. Fritsch (2018) argues that the concentric, circular church plan in Ethiopia is based, in part, on precedents in Nubian church architecture. |

| 44 | For a discussion of the meaning of these terms and possible sources of origin, see (Kribus forthcoming a). |

| 45 | For a preliminary typology of Betä Ǝsraʾel prayer houses and a discussion regarding their chronology, see (Kribus 2022, pp. 77–86). |

| 46 | For an overview on the Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic wars with references to relevant sources, see (Kaplan 1992, pp. 79–96; Quirin 1992, pp. 40–88). |

| 47 | For a detailed account of the different versions documented to date, see (Kribus 2022, pp. 95–99; Wovite Worku Mengisto and Kribus forthcoming) It should be noted that the Betä Ǝsraʾel relayed their historiography orally, and accounts of their past were not committed to writing by the community until recent generations. |

| 48 | For an overview of this conflict, see (Kaplan 1992, pp. 56–58; Quirin 1992, pp. 52–57). A few accounts situated the events at the time of the wars between the Betä Ǝsraʾel and the Solomonic monarch Śärṣä Dǝngǝl (1563–1597, Kahana 1977, p. 164), or in the context of a raid of Sudanese Mahdists (such raids took place in the northern Ethiopian Highlands from 1885 to 1889). According to the latter version, the religion which was being forcefully imposed was Islam rather than Christianity (Rosen 2018). |

| 49 | While accounts of this event do not appear in Christian Solomonic sources describing the campaigns against the Betä Ǝsraʾel, there are comparable accounts of members of the community committing suicide rather than be taken captive. Notable among them is a description appearing in the chronicle of the Solomonic monarch Śärṣä Dǝngǝl, of a captive Betä Ǝsraʾel woman who threw herself and her captor off a cliff. The chronicle’s author adds that several other Betä Ǝsraʾel women did the same (Conti Rossini 1907, pp. 88–89). |

| 50 | The composition and chronology of Tarikä Nägäśt compilations vary considerably, and often, local and regional considerations had an impact on their content. The eclectic nature of such works, and the uncertain provenance of much of their source material has posed a challenge to scholarship, and while individual works have been published, a comprehensive study of this genre has yet to be undertaken. |

| 51 | My translation. This account appears in a yet-unpublished paper manuscript, originally from Däbrä Ṣǝge Maryam monastery in Šäwa. A digital version (EMML 7334) is available at the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library. The date of the production of the manuscript has not yet been determined, but it is clear that it significantly post-dates the events described. |

| 52 | My translation. The content of the manuscript containing this account, of suggested eighteenth-century provenance, was published by Basset (1882, pp. 11–12). |

References

- Abbink, Jon. 1990. The Enigma of Beta Esra’el Ethnogenesis. An Anthro-Historical Study. Cahiers D’études Africaines 120: 397–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balicka-Witakowska, Ewa. 2005. Däbrä Sina. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 46–47. [Google Scholar]

- Basset, René. 1882. Études sur l’histoire d’Éthiopie. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale. [Google Scholar]

- Belachew, Mekete, and Alain Gascon. 2005. Däbrä Zäyt. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 52–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Dor, Shoshana. 1985a. Ha-Meqomot ha-Qədošim šel Yehūdey ʾEtiyopiyah. [The Holy Places of Ethiopian Jewry]. Peʿamim 22: 32–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Dor, Shoshana. 1985b. Ha-Sigd šel Beyṯa Yiśraʾel (ʿAdaṯ Yehūdey ʾEtiyopiyah, ha-Məḵūnim Falašim). Ḥag Ḥidūš ha-Brit. [The Sigd of the Beta Israel (The Community of Ethiopian Jews, Who are Known as Falashas). The Holiday of Renewal of the Covenant]. Master’s dissertation, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Bosc-Tiessé, Claire. 2005. Gälila. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 659–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, James. 1790. Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile in the Years 1768, 1769, 1770, 1771, 1772 and 1773. 5 vols. Edinburgh: R. Ruthven. [Google Scholar]

- Buxton, David, and Derek Matthews. 1971–1972. The Reconstruction of Vanished Aksumite Buildings. Rassegna di Studi Etiopici 25: 53–77.

- Conti Rossini, Carlo. 1907. Historia regis Sarṣa Dengel (Malak Sagad). Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 21. Paris: E Typographeo Reipublicae. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, Bernard. 1960. Synoptic Presentation of the Eucharist as Covenant Sacrifice. Theological Studies 21: 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dege-Müller, Sophia, and Bar Kribus. 2021. The Veneration of St. Yared – A Multireligious Landscape Shared by Ethiopian Orthodox Christians and the Betä Ǝsraʾel (Ethiopian Jews). In Geographies of Encounter. The Making and Unmaking of Multi-Religious Spaces. Edited by Marian Burchardt and Maria Chiara Giorda. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 255–80. [Google Scholar]

- Derat, Marie-Laure. 2007. Lalibäla. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 3, pp. 477–80. [Google Scholar]

- di Salvo, Mario. 1999. Churches of Ethiopia. The Monastery of Nārgā Śellāsē. Milano: Skira Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Fiaccadori, Gianfranco. 2007. Mǝnilǝk I. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 3, pp. 921–22. [Google Scholar]

- Finneran, Niall. 2007. The Archaeology of Ethiopia. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Flad, Johann Martin. 1869. The Falashas (Jews) of Abyssinia. Translated by S. P. Goodhart. London: William Macintosh. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch, Emmanuel. 2018. The Origins and Meanings of the Ethiopian Circular Church: Fresh Explorations. In Tomb and Temple. Re-Imagining the Sacred Buildings of Jerusalem. Edited by Robin Griffith-Jones and Eric Fernie. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, pp. 267–93. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch, Emmanuel, and Michael Gervers. 2007. Pastophoria and Altars: Interaction in Ethiopian Liturgy and Church Architecture. Aethiopica 10: 7–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhin, Ezra. 2007. Maḫlet. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 3, pp. 659–60. [Google Scholar]

- HaCohen, Ran. 2009. Kǝḇod ha-Melaḵim. Ha-ʾEpos ha-Leʾumi ha-ʾEtiyopi. [Kebra Nagast. Translated from Geʿez, annotated and Introduced by Ran HaCohen]. Tel Aviv: Haim Rubin Tel Aviv University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ḥädanä Təkuyä, qes. 2011. Mə-Gondar lə-Yerūšalayim. Moṣaʿam, Toldoteyhem ve-Qorot Ḥayeyhem šel Yehūdey ʾEtiyopiyah. [From Gondar to Jerusalem: The Origin, History and Lives of the Jews of Ethiopia]. Beit Shemesh: Mishkan. [Google Scholar]

- Har’el, Dan. 1963. Yoman Biqūr be-Kəfarey ha-Falašim be-Harey Semyien. [Journal of a Visit to the Falasha Villages in the Semien Mountains] Unpublished.

- Heldman, Marilyn. 1992. Architectural Symbolism, Sacred Geography and the Ethiopian Church. Journal of Religion in Africa 22: 222–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldman, Marilyn. 2003. Church Buildings. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 1, pp. 737–740. [Google Scholar]

- Heldman, Marilyn. 2005. Gännätä Maryam. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 692–93. [Google Scholar]

- Henze, Paul B. 2005a. Däbrä Sina. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 47–48. [Google Scholar]

- Henze, Paul B. 2005b. Gälila. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2, p. 660. [Google Scholar]

- Henze, Paul B. 2007. Nazret. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 3, pp. 1158–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana, Ya’el. 1977. ʾAḥim Šəḥorim. Ḥayim be-Qereḇ ha-Falašim. [Black Brothers. Life Among the Falashas]. Tel Aviv: Am Oved. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Steven. 1992. The Beta Israel (Falasha) in Ethiopia. From the Earliest Times to the Twentieth Century. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Steven. 2011. Solomonic Dynasty. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig and Alessandro Bausi. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 4, pp. 688–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Samantha. 2020. Medieval Ethiopian Diasporas. In A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea. Edited by Samantha Kelly. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 425–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kidane, Habtemichael. 2011. Qəne. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig and Alessandro Bausi. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 4, pp. 283–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kribus, Bar. 2022. Ethiopian Jewish Ascetic Religious Communities: Built Environment and Way of Life of the Betä Ǝsraʾel. Leeds: ARC Humanities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kribus, Bar. Forthcoming a. Architectural and Religious Symbolism in the Betä Ǝsraʾel (Ethiopian Jewish) Prayer House. Rassegna di Studi Etiopici.

- Kribus, Bar. Forthcoming b. The Campaign of the Solomonic Monarch Yəsḥaq (1414–1429/30) as a Turning Point in Betä Ǝsraʾel History: Its Commemoration in Solomonic and Betä Ǝsraʾel Sources and Holy Sites. Aethiopica.

- Lepage, Claude, and Jacques Mercier. 2005. Ethiopian Art. The Ancient Churches of Tigrai. Paris: ADPF Éditions et Recherche sur les Civilisations. [Google Scholar]

- Leslau, Wolf. 1951. Falasha Anthology. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leslau, Wolf. 1974. Taamrat Emmanuel’s Notes on Falasha Monks and Holy Places. In Salo Wittmayer Baron Jubilee Volume. Edited by Saul Lieberman and Arthur Hyman. Jerusalem: American Academy for Jewish Research, pp. 623–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lifchitz, Deborah. 1939. Un sacrifice chez les Falacha, Juifs abyssins. La Terre et la vie 9: 116–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lusini, Gianfrancesco. 2005a. Däbrä Ṣǝyon. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lusini, Gianfrancesco. 2005b. Däbrä Sina. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 45–46. [Google Scholar]

- Marrassini, Paolo. 2007. Kǝbrä nägäśt. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 3, pp. 364–68. [Google Scholar]

- Mengisto, Wovite Worku, and Bar Kribus. Forthcoming. Ḥayim Yehūdiyim bə-Arṣam šel ha-Gidʿonim. Qehilat Beyṯa Yiśraʾel (Yehūdey ʾEtiyopiyah) bə-Harey Səmen. [Jewish Life in the Land of the Gideonites: The Betä Ǝsraʾel (Ethiopian Jews) in the Sǝmen Mountains]. Tel Aviv: State Corporation of Ethiopian Jewish Heritage Center, Submitted.

- Munro-Hay, Stuart. 1991. Aksum. An African Civilization of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Munro-Hay, Stuart. 2003. Aksum Ṣəyon. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 1, pp. 183–85. [Google Scholar]

- Munro-Hay, Stuart. 2005. The Quest for the Ark of the Covenant. A True History of the Tablets of Moses. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Omer, Ahmed Hassen. 2005. Däbrä Sina. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Pankhurst, Richard. 2005. Däbrä Tabor. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, Kirsten Stoffregen. 2007. Jerusalem. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 3, pp. 273–77. [Google Scholar]

- Perruchon, Jules François Célestin. 1892. Vie de Lalibala roi d’Éthiopie. Paris: Ernest Leroux. [Google Scholar]

- Perruchon, Jules François Célestin. 1893. Les chroniques de Zar’a Ya’eqob et de Ba’eda Mâryâm. Paris: Émile Bouillon. [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson, David W. 2009. Ancient Churches of Ethiopia: Fourth–Fourteenth Centuries. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson, David W. 2012. Foundations of an African Civilisation. Aksum and the Northern Horn 1000 BC—AD 1300. Rochester: James Currey, Boydell & Brewer Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Quirin, James. 1992. The Evolution of the Ethiopian Jews. A History of the Beta Israel (Falasha) to 1920. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, Yikhat. 2018. “Maʿayan ha-Giborim”. [Spring of the Heroes]. Available online: http://halachayomit.com/Rozenyikhat/YKR%20sipurei%20gvura%20Ethiopians.doc (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Safrai, Ze’ev. 1989. From the Synagogue to ‘Little Temple’. In Proceedings of the Tenth World Congress of Jewish Studies. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Salamon, Hagar. 1999. The Hyena People. Ethiopian Jews in Christian Ethiopia. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sellassie, Sergew Hable. 1972. Ancient and Medieval Ethiopian History to 1270. Addis Abäba: United Printers. [Google Scholar]

- Shelemay, Kay Kaufman. 1989. Music, Ritual, and Falasha History. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Henry Aaron. 1862. Wanderings among the Falashas in Abyssinia. Together with a Description of the Country and its Various Inhabitants. London: Wertheim, Macintosh and Hunt. [Google Scholar]

- Ullendorff, Edward. 1968. Ethiopia and the Bible. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- von Lüpke, Theodor. 1913. Deutsche Aksum-Expedition. Band III: Profan- und Kultbauten Nordabessiniens. Berlin: Georg Reimer. [Google Scholar]

- Waldman, Menachem. 1989. Meʿever le-Naharey Kūš. Yehūdey ʾEtiyopiyah ve-ha-ʿAm ha-Yehūdi. [Beyond the Rivers of Ethiopia. The Jews of Ethiopia and the Jewish People]. Tel Aviv: Ministry of Defense. [Google Scholar]

- Waldman, Menachem. 2015. Masaʿ ʾel Šeʾerit Yehūdey ʾEtiyopiyah. [First Contact. Finding the Last Ethiopian Jews]. Jerusalem: Ben-Zvi Institute for the Study of Jewish Communities in the East. [Google Scholar]

- Waldman, Menachem. 2018. Divrey Aba Yiẓḥaq. [The Words of Abba Yǝsḥaq]. Peʿamim 154–55: 279–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ziv, Yossi. 2017. Ḥag w-Moʿed be-Beyta Yiśraʾel. [Festival and Holiday in the Ethiopian Jewish Tradition of Beta Israel]. Tel Aviv: Yad Ben Zvi and the Mofet Institute. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kribus, B. Jewish–Christian Interaction in Ethiopia as Reflected in Sacred Geography: Expressing Affinity with Jerusalem and the Holy Land and Comemorating the Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic Wars. Religions 2022, 13, 1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13121154

Kribus B. Jewish–Christian Interaction in Ethiopia as Reflected in Sacred Geography: Expressing Affinity with Jerusalem and the Holy Land and Comemorating the Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic Wars. Religions. 2022; 13(12):1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13121154

Chicago/Turabian StyleKribus, Bar. 2022. "Jewish–Christian Interaction in Ethiopia as Reflected in Sacred Geography: Expressing Affinity with Jerusalem and the Holy Land and Comemorating the Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic Wars" Religions 13, no. 12: 1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13121154

APA StyleKribus, B. (2022). Jewish–Christian Interaction in Ethiopia as Reflected in Sacred Geography: Expressing Affinity with Jerusalem and the Holy Land and Comemorating the Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic Wars. Religions, 13(12), 1154. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13121154