Reception History and Early Chinese Classics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. How We Learn to Read Texts: A Personal View on Interpretive Communities

3. Originalist Readings of the Chinese Classics

The Xiang’er commentary is the earliest Daoist interpretation of the Laozi [and] the Laozi itself tells us nothing of the Daoist religion. Although the Celestial Masters accorded the Laozi primacy over other revealed texts as a catechism of their faith, their veneration seems to have been directed more to the figure of Laozi (or Lord Lao, as he was called) than to the ideas contemporaries found in the Laozi itself, for their interpretations often run counter to the clear intent of the text.

4. What Is a Text in Premodern China?

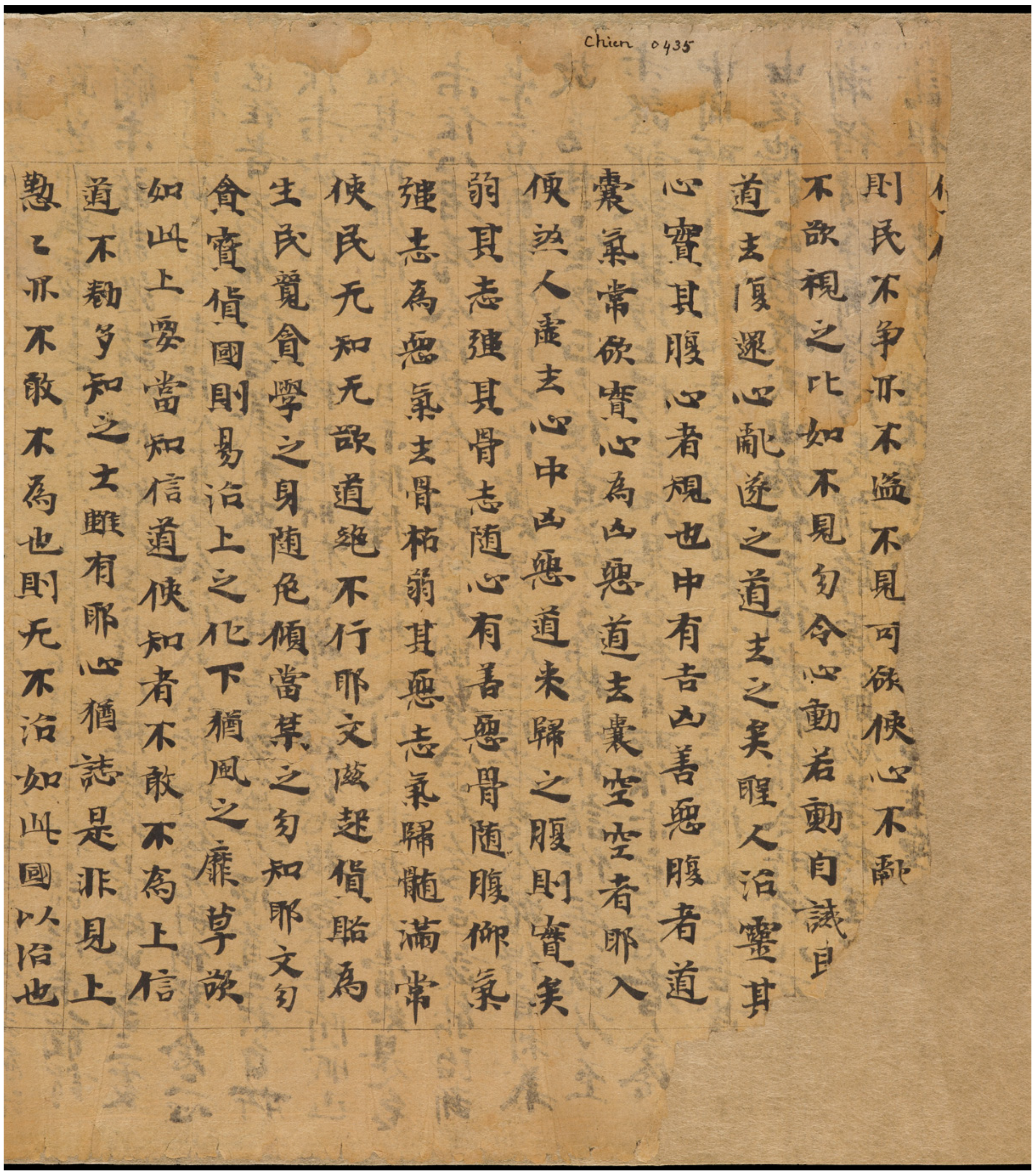

Before the reader gets to see the first line of the base text, he has already read a structuring comment which relates the chapter to the previous one [and] an outline of the arguments the chapter will propose … In the Dunhuang manuscript P 2517 … these parts are in regular-sized characters, just like the cited base text. Only the interlinear commentary to the single lines is in smaller-sized characters.

5. A Shift in Focus: From Author- to Reader-Response-Centered Interpretations

[The work] lives as long as its influence lasts. The influence of a work includes an event that affects both the consumer of the work and the work itself. What happens to the work is an expression of what the work is … The work is a work and lives as a work because it calls for interpretations and because it has an influence of many meanings.

6. Conclusions: Why It Is Worthwhile to Explore the Reception History of Classics

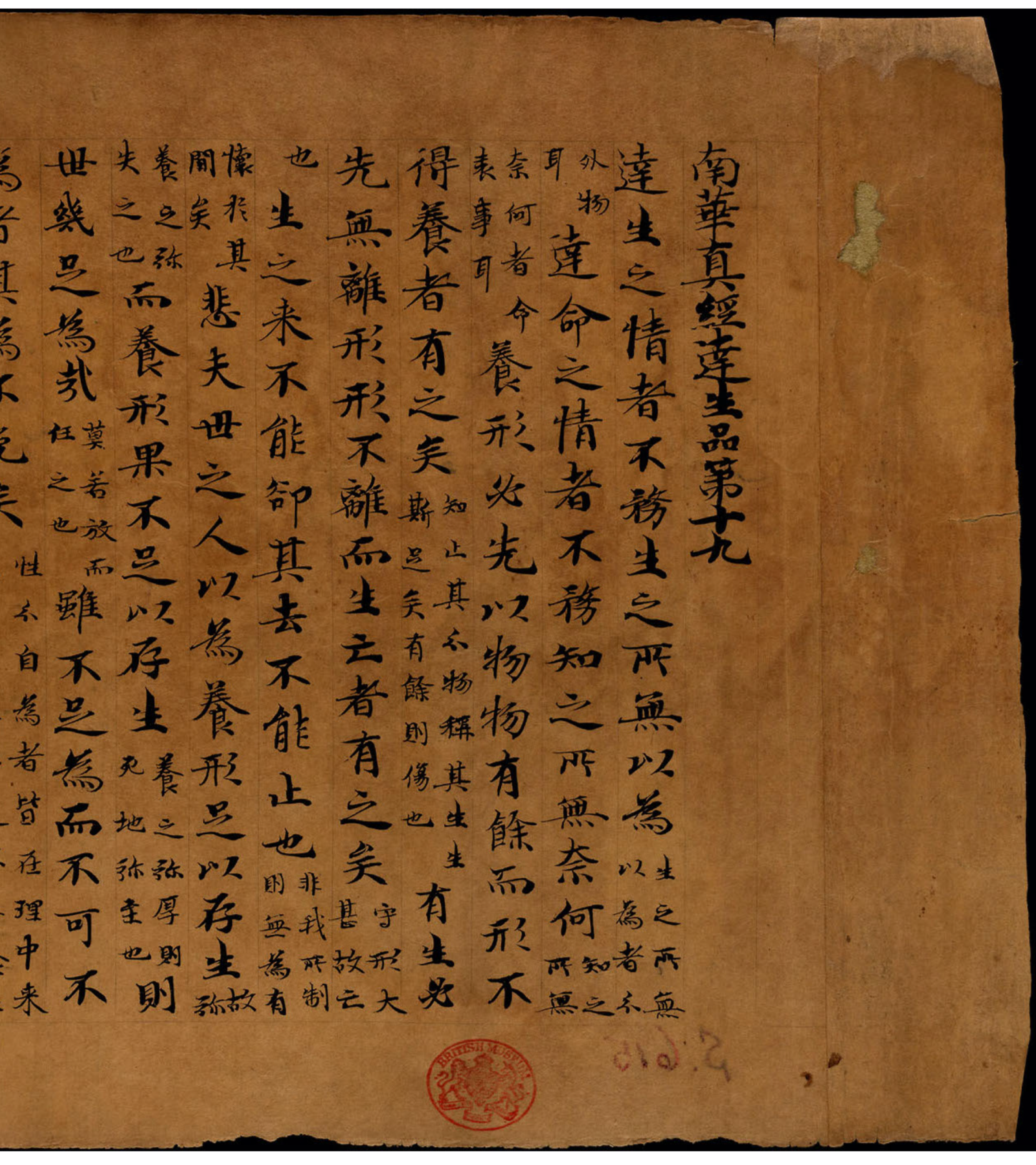

There was nothing on which his [i.e., Zhuangzi’s] teachings did not touch, but in their essentials they went back to the words of Laozi. Thus his works, over 100,000 characters, all consisted of allegories. He wrote “Yufu” 漁父 (The Old Fisherman), “Dao Zhi” 盜跖 (The Bandit Zhi), and “Quqie” 胠篋 (Ransacking Baggage) in which he mocked the likes of Confucius and made clear the policies of Laozi.

其學無所不闚,然其要本歸於老子之言。其著書十餘萬言,大抵率寓言也。作漁父、盜跖、胠篋,以詆訿孔子之徒,以明老子之術。

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In this article, I use the term classic in a wider sense than the Chinese term jing 經 is commonly used. In my understanding, it refers to any text that has accumulated a significant exegetical tradition in the form of commentaries, translations, and reworkings in various cultural products. |

| 2 | For a discussion of the same hermeneutic phenomenon, see the section “Authorial Intentionialism and Its Limits” in (Sarafinas 2022). |

| 3 | I use the term biography in relation to books since it reflects the idea that a text goes through different stages of existence, like human beings. The same vision is reflected in Princeton University Press’ series “Lives of Great Religious Books.” See https://press.princeton.edu/series/lives-of-great-religious-books, accessed on 10 December 2022. |

| 4 | I agree with most scholars of “religious” Daoism that we may only find a concrete community of people in the first and second century CE that formed a distinct group we may nowadays term Daoist. But unlike most scholars of early China or Michel Strickmann (1942–1994) and his students of later Daoist movements, who see a strict division between what scholars in early China oftentimes call early “philosophical” Daoism and later “religious” Daoism, I perceive a discontinuous continuity between these two “movements” in the form of shared terminologies, concepts, and practices. In other words, I follow Kristofer Schipper’s (1934–2021) vision and call texts like the Laozi, Zhuangzi, or even by extension the Huainanzi, proto-Daoist, since they at least partially informed the lifeworlds and imaginaires of later Daoist practitioners. |

| 5 | Sheldon Pollock divides philology into three “dimensions”: a text’s genesis, its tradition of reception, and its presence to the philologist’s own subjectivity (Pollock 2014). In my opinion, the first dimension outplays the other two in the field of early China. |

| 6 | For a discussion of “kaozheng-scholarship [as] a step toward indigenous development of an empirical mode of scholarship, even of modern science” (Quirin 1996, p. 36), see (Elman 1984). For a critique of readings that see the rise of modernity and scientific methods detached from ethical and moral concerns central for Confucian discourse in the Qing dynasty, see (Quirin 1996). For a discussion of the racist undertones of the purity discourse that guided the rise of the discipline of philology, see (Lin 2016). |

| 7 | Interestingly, rabbinic readings of the bible emphasize the multivalency of the text of which “multiple meanings [can] be derived from and are inherent in every [biblical] event, for every event is full of reverberations, references, and patterns of identity that can be infinitely extended” (Handelmann 1982, p. 37). I learned about Handelmann’s work from (Wagner 2012, p. 65). |

| 8 | I would like to thank my colleague Alexei Ditter who reminded me that the performance and recitation of texts can enable an audience to experience stylistic differences between texts even if these distinctions are not reflected in the visual design of a manuscript. In that sense, separating commentary and main text on a visual level would be similar to the practice of adding punctuation to early Chinese manuscripts: apparently, neither of these technolgies were needed by early audiences according to such a reading since they knew their texts by heart. |

| 9 | Hans van Ess argues that from the Han onward linguistic changes rendered the language of ancient classics so obscure to readers at the time that commentaries and phonetic glosses became a necessity for any engagements with the classics (van Ess 2009, pp. 216–25). Acording to Michael Puett, this attitude to commentaries as ”the only source of access to the earlier material” changed only with Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200) in the twelfth century, whose orientation toward the classics I present on pages 8–9 (Puett 2021, pp. 105–6). |

| 10 | I would like to thank Mark Csikszentmihalyi who made me aware of this possible reading of the “Butterfly Dream’s” coda. |

| 11 | As a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin, I met a colleague who displayed a similar take on the relationship between main text and commentary. In my first class on the Zhuangzi’s reception history in 2008, the said classmate repeatedly responded to the question of what is the meaning of a cryptic Zhuangzi passage by simply translating or summarizing Guo Xiang’s commentary, effectively equating the main text with one of its interpretations. |

| 12 | For a radically different interpretation of the term “work” that reads it as the “receptacle of the Author’s meaning” (Sarafinas 2022, p. 2), see (Barthes 1977). |

| 13 | There is a sizable amount of scholarship that could be categorized as studies in readings of early Chinese classics. However, very few of the examples mentioned in this footnote explicitly frame their work in such terms and engage with commentaries without referencing the field of reception history. For a few examples that engage with the reception history of the Lunyu, see (Ashmore 2010, pp. 111–97; Fuehrer 2002, 2009; Makeham 2003; Swartz 2008). For a few examples that engage with the reception history of the Yi jing, see (Schilling 1998; Smith et al. 1990; Smith 2008, 2012). For a few examples that engage with the reception history of the Laozi, see (Tadd 2022a; Chan 1991; Wagner 2000). For a few examples that engage with the Zhuangzi’s reception, see n.16 below. |

| 14 | For an example of a scholarly work that “shifts the emphasis from the author as the main creator and ultimate arbiter of a text’s meaning to the editors and publishers, collectors and readers, producers and viewers, through whose hands a text, genre, or legend is reshaped, disseminated, and given new meanings” (pp. 1–2), see (Zeitlin et al. 2003). |

| 15 | For two projects that explore the varying images of Confucius, see (Csikszentmihalyi 2001; Nylan and Wilson 2010). |

| 16 | For a few examples of excellent work on the Zhuangzi’s reception, see (Angles 2020; Brackenridge 2010; Chai 2008; Chapman 2010; Choi 2010; Epstein 2006; Fang 2008; Harack 2007; Idema 2014; Liu 2016; Möller 1999; Qiu 2005; Saso 1983; Saussy 2017; Specht 1998; Swartz 2018; Tang 1983; Wang 2003; Xiong et al. 2003; Yu 2000; Zhang 2018; Ziporyn 2003). |

| 17 | I changed the transliterations from Wade-Giles to Pinyin in this quotation. |

References

- Angles, Jean. 2020. Why and How to Read the Zhuangzi? Late Ming Neidan Master Cheng Yining’s Answer. Journal of National Taiwan Normal University 師大學報 65: 149–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore, Robert. 2010. The Transport of Reading: Text and Understanding in the World of Tao Qian (365–427). Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Assandri, Friederike. 2022. Structure and Meaning in the Interpretation of the Laozi: Cheng Xuanying’s Hermeneutic Toolkit and His Interpretation of Dao as a Compassionate Savior. Religions 13: 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthes, Roland. 1977. The Death of the Author. In Image-Music-Text. Translated and Edited by Stephen Heath. New York: Hill and Wang, pp. 142–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bokenkamp, Stephen E. 1997. ed. and trans. Early Daoist Scriptures. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brackenridge, Scot. 2010. The Character of Wei-Jin Qingtan: Reading Guo Xiang’s Zhuangzi Commentary as an Expression of Political Practice. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, E. Bruce, and A. Taeko Brooks. 1998. eds. and trans. The Original Analects: Sayings of Confucius and His Successors. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, David. 2008. Early Zhuangzi Commentaries: On the Sounds and Meanings of the Inner Chapters. Saarbrücken: Verlag Dr. Müller. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Alan K. L. 1991. Two Visions of the Way: A Study of the Wang Pi and the Ho-Shang Kung Commentaries on the Lao-tzu. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, Jesse. 2010. Passivity and Progress: Yan Fu, Hu Shi, and Liang Qichao on the Laozi and the Zhuangzi. Master’s thesis, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Kuan-hsing. 2010. Asia as Method: Toward De-Imperialization. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Anne. 1993. Ch’un ch’iu 春秋, Kung yang 公羊, Ku liang 穀梁, and Tso chuan 左傳. In Early Chinese Texts: A Biographical Guide. Edited by Michael Loewe. Berkeley: The Society for the Study of Early China and the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, pp. 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Jin-Hee 崔珍皙. 2010. Cheng Xuanying Zhuangzi shu yanjiu 成玄英莊子疏研究. Chengdu: Bashu shushe. [Google Scholar]

- Constantini, Filippo. 2022. The LATAM’s Laozi: The Reception and Interpretations of the Laozi in Latin America. Religions 13: 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Scott, ed. 2003. Hiding the World in the World: Uneven Discourses on the Zhuangzi. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mark. 2001. Confucius. In Rivers of Paradise: Moses, Buddha, Confucius, Jesus, and Muhammad as Religious Founders. Edited by David Noel Freedman and Michael J. McClymond. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, pp. 233–308. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio, Paul Joseph. 2022. Wang Bi’s ‘Confucian’ Laozi: Commensurable Ethical Understandings in ‘Daoist’ and ‘Confucian’ Thinking. Religions 13: 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Donald R., Jr. 2015. Three Principles for an Asian Humanities: Care First ... Learn From ... Connect Histories. Journal of Asian Studies 74: 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denecke, Wiebke. 2011. The Dynamics of Masters Literature: Early Chinese Thought from Confucius to Han Feizi. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Heng. 2018. The Author’s Two Bodies: Paratext in Early Chinese Textual Culture. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Elman, Benjamin A. 1984. From Philosophy to Philology: Intellectual and Social Aspects of Change in Late Imperial China. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Shari. 2006. Boundaries of the Dao: Hanshan Deqing’s (1546–1623) Buddhist Commentary on the Zhuangzi. Ph.D. dissertation, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Erkes, Eduard. 1945. Ho-Shang Kung’s Commentary on Lao-tse. Artibus Asiae 8: 119–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkes, Eduard. 1946. Ho-Shang Kung’s Commentary on Lao-tse. II (Continued). Artibus Asiae 9: 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkes, Eduard. 1949. Ho-Shang Kung’s Commentary on Lao-tse. III (Concluded). Artibus Asiae 12: 221–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Yong 方勇, ed. 2008. Zhuangzi xueshi 莊子學史. Beijing: Renmin chuban she. [Google Scholar]

- Fish, Stanley. 2001. Yet Once More. In Reception Study: From Literary Theory to Cultural Studies. Edited by James L. Machor and Philip Goldstein. New York: Routledge, pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fuehrer, Bernhard. 2002. Did the Master Instruct His Followers to Attack Heretics? A Note on Readings of Lunyu 2.16. In Reading East Asian Writing. The Limits of Literary Theory. Edited by Michel Hockx and Ivo Smits. London: Routledge Curzon, pp. 117–58. [Google Scholar]

- Fuehrer, Bernhard. 2009. Exegetical Strategies and Commentarial Features of Huang Kan’s Lunyu [jijie] yishu. In Dongya Lunyuxue: Zhongguo pian 東亞論語學: 中國篇. Edited by Huang Chun-chieh. Taipei: National Taiwan University Press, pp. 274–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg. 1989. Truth and Method. Translated by Joel Weinsheimer, and Donald G. Marshall. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Yuhan. 2022. Rethinking Guo Xiang’s Concept of ‘Nothing’ in the Perspective of His Reception of Laozi and Zhuangzi. Religions 13: 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Daniel K., trans. 1990. Learning to Be a Sage: Selections from Conversations of Master Chu, Arranged Topically. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Genette, Gérard. 1991. Introduction to the Paratext. Translated by Marie Maclean. New Literary History 22: 261–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafton, Anthony. 2015. Humanist Philologies: Texts, Antiquities, and their Scholarly Transformation in the Early Modern West. In World Philology. Edited by Sheldon Pollock, Benjamin A. Elman and Ku-ming Kevin Chang. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 154–77. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Angus C. 1981. ed. and trans. Chuang-tzŭ: The Seven Inner Chapters and Other Writings from the Book Chuang-tzŭ. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Angus C. 1989. Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China. La Salle: Open Court Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Qingfan 郭慶藩, ed. 1954. Zhuangzi jishi 莊子集釋. In Zhuzi jicheng 諸子集成. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hadhri, Sana, Zixiao Liu, and Zhihong Wu. 2022. The Dissemination of Laozi’s Text and Thought in the Arab World. Religions 13: 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelmann, Susan. 1982. The Slayers of Moses: The Emergence of Rabbinic Interpretation in Modern Literary Theory. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harack, Michael. 2007. Cheng Xuanying’s Conception of the Sage in the Zhuangzi. Master’s thesis, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, Hans Peter. 2001. Die Welt als Wendung: Zu einer Literarischen Lektüre des Wahren Buches vom Südlichen Blütenland. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Idema, Wilt, trans. 2014. The Resurrected Skeleton: From Zhuangzi to Lu Xun. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jaspers, Karl. 1954. Way to Wisdom: An Introduction to Philosophy. Translated by Ralph Manheim. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jauss, Hans Robert. 1982. Literary History as a Challenge to Literary Theory. In Toward an Aesthetic of Reception. Translated by Timothi Bahti. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 3–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kjellberg, Paul, and Philip J. Ivanhoe, eds. 1996. Essays on Skepticism, Relativism, and Ethics in the Zhuangzi. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kleeman, Terry F. 2016. Celestial Masters: History and Ritual in Early Daoist Communities. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Esther. 2011. Were there “Inner Chapters” in the Warring States? A New Examination of Evidence about the Zhuangzi. T’oung Pao 96: 299–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosík, Karel. 1976. Dialectics of the Concrete: A Study of the Problems of Man and the World. Boston: D. Reidel Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Kristeva, Julia. 1969. Semiotiké: Recherches pour une sémanalyse. Paris: Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Yii-jan. 2016. The Erotic Life of Manuscripts: New Testament Textual Criticism and the Biological Sciences. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Jianmei. 2016. Zhuangzi and Modern Chinese Literature. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Xiaogan. 1994. Classifying the Zhuangzi Chapters. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Xie 劉勰. 1978. Wenxin diaolong 文心雕龍. Beijing: Renmin wenxue. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, Richard John, trans. 2004. The Classic of the Way and Virtue: A New Translation of the Tao-te Ching of Laozi as Interpreted by Wang Bi. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, Victor H., ed. 1983. Experimental Essays on Chuang-tzu. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, Victor H., trans. 1994. Wandering on the Way: Early Taoist Tales and Parables of Chuang Tzu. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Makeham, John. 2003. Transmitters and Creators: Chinese Commentators and Commentaries on the Analects. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Meulenbeld, Mark. 2012. From ‘Withered Wood’ to ‘Dead Ashes’: Burning Bodies, Metamorphosis, and the Ritual Production of Power. Cahiers d’Extrême Asie 19: 217–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, Thomas. 2022. The Original Text of the Daodejing: Disentangling Versions and Recensions. Religions 13: 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, Hans-Georg. 1999. Zhuangzi’s Butterfly Dream: A Daoist Interpretation. Philosophy East and West 49: 439–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylan, Michael, and Thomas Wilson. 2010. Lives of Confucius: Civilization’s Greatest Sage through the Ages. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, Sheldon. 2014. Philology in Three Dimensions. Postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 5: 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, Sheldon. 2015. Introduction. In World Philology. Edited by Sheldon Pollock, Benjamin A. Elman and Ku-ming Kevin Chang. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Puett, Michael J. 2021. Impagination, Reading, and Interpretation in Early Chinese Texts. In Impagination—Layout and Materiality of Writing and Publication: Interdisciplinary Approaches from East and West. Edited by Ku-ming (Kevin) Chang, Anthony Grafton and Glenn W. Most. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Peipei. 2005. Bashō and the Dao: The Zhuangzi and the Transformation of Haikai. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quirin, Michael. 1996. Scholarship, Value, Method, and Hermeneutics in Kaozheng: Some Reflections on Cui Shu (1740–1816) and the Confucian Classics. History and Theory 35: 34–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roetz, Heiner. 1992. Die chinesische Ethik der Achsenzeit: Eine Rekonstruktion unter dem Aspekt des Durchbruchs zu postkonventionellem Denken. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. [Google Scholar]

- Sarafinas, Daniel. 2022. The Hierarchy of Authorship in the Hermeneutics of the Daodejing. Religions 13: 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saso, Michael. 1983. The Chuang-tzu nei-p’ien: A Taoist Meditation. In Experimental Essays on Chuang-tzu. Edited by Victor H. Mair. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, pp. 140–57. [Google Scholar]

- Saussy, Haun. 2017. Translation as Citation: Zhuangzi Inside Out. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling, Dennis. 1998. Spruch und Zahl: Die chinesischen Orakelbücher ‘Kanon des Höchsten Geheimen’ und ‘Wald der Wandlungen’ aus der Han-Zeit. Aalen: Scientia Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Seo-Reich, Heejung. 2022. Four Approaches to Daodejing Translations and Their Characteristics in Korean after Liberation from Japan. Religions 13: 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Vincent Yu-Chung, trans. 2015. The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons: A Study Of Thought And Pattern In Chinese Literature. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sima, Qian. 1994. The Grand Scribe’s Records, Volume VII: The Memoirs of Pre-Han China. Edited by William H. Nienhauser Jr. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sima, Qian 司馬遷. 1962. Shiji 史記. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Kidder, Jr., Peter K. Bol, Joseph A. Adler, and Don J. Wyatt, eds. 1990. Sung Dynasty Uses of the I Ching. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Richard J. 2008. Fathoming the Cosmos and Ordering the World: The Yijing (I Ching, or Classic of Changes) and Its Evolution in China. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Richard J. 2012. The I Ching: A Biography. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Specht, Annette. 1998. Der Zhuangzi Kommentar des Zhu Dezhi (fl. 16. Jh.): Zur Rezeption des Zhuangzi in der Ming-Zeit. Hamburg: Verlag Dr. Kovač. [Google Scholar]

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. 2003. Death of a Discipline. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz, Wendy. 2008. Reading Tao Yuanming: Shifting Paradigms of Historical Reception (427–1900). Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz, Wendy. 2018. Reading Philosophy, Writing Poetry: Intertextual Modes of Making Meaning in Early Medieval China. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Tadd, Misha. 2022a. Global Laozegetics: A Study in Globalized Philosophy. Journal of the History of Ideas 83: 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadd, Misha. 2022b. The Translingual Ziran of Laozi Chapter 25: Global Laozegetics and Meaning Unbound by Language. Religions 13: 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadd, Misha. 2022c. What is Global Laozegetics?: Origins, Contents, and Significance. Religions 13: 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Yijie 湯一介. 1983. Guo Xiang yu Wei Jin xuanxue 郭象與魏晉玄學. Wuhan: Hubei renmin chuban she. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaševskij, Boris. 2000. Literatur und Biographie. Translated by Sebastian Donat. In Texte zur Theorie der Autorschaft. Edited by Fotis Jannidis, Gerhard Lauer, Mathias Martinez and Simone Winko. Stuttgart: Philipp Reclam, Jr., pp. 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- van Ess, Hans. 2009. Die Bedeutung des Zitats für die konfuzianische Tradition in China. In Sakrale Texte: Hermeneutik und Lebenspraxis in den Schriftkulturen. Edited by Wolfgang Reinhard. München: C. H. Beck Verlag, pp. 216–43. [Google Scholar]

- van Norden, Bryan W. 2007. Virtue Ethics and Consequentialism in Early Chinese Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Rudolf G. 2000. The Craft of a Chinese Commentator: Wang Bi on the Laozi. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Rachel. 2012. Godwired: Religion, Ritual and Virtual Reality. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Youru. 2003. Linguistic Strategies in Daoist Zhuangzi and Chan Buddhism: The Other Way of Speaking. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Tieji 熊鐵基, Gusheng Liu 劉固盛, and Shaojun Liu 劉韶軍, eds. 2003. Zhongguo Zhuangxue shi 中國莊學史. Changsha: Hunan renmin chuban she. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Dadui. 2022. Qian Xuexi and William Empson’s Discussion of Arthur Waley’s English Translation of the Daodejing. Religions 13: 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Shiyi. 2000. Reading the Chuang-tzu in the Tang Dynasty: The Commentary of Ch’eng Hsüan-Ying (fl. 631–652). New York: Peter Lang Publishing Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Zeitlin, Judith T., Lydia H. Liu, and Ellen Widmer, eds. 2003. Writing and Materiality in China: Essays in Honor of Patrick Hanan. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Can, and Pan Xie. 2022. Challenge and Revolution: An Analysis of Stanislas Julien’s Translation of the Daodejing. Religions 13: 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Hongyan, and Jing Luo. 2022. Interpretive Trends and the Conceptual Construction of the Daodejing’s Dao in Russian Sinology: A Historical Overview. Religions 13: 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Shuheng. 2018. Forming the Image of Cheng Xuanying (ca. 600–690). Master’s thesis, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Yubo, and Weihan Song. 2022. The Shifting Depictions of Xiàng in German Translations of the Dao De Jing: An Analysis from the Perspective of Conceptual Metaphor Field Theory. Religions 13: 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziporyn, Brook. 2003. The Penumbra Unbound: The Neo-Taoist Philosophy of Guo Xiang. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zürn, Tobias Benedikt. 2020. The Han Imaginaire of Writing as Weaving: Intertextuality and the Huainanzi’s Self-Fashioning as an Embodiment of the Way. Journal of Asian Studies 79: 367–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zürn, T.B. Reception History and Early Chinese Classics. Religions 2022, 13, 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13121224

Zürn TB. Reception History and Early Chinese Classics. Religions. 2022; 13(12):1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13121224

Chicago/Turabian StyleZürn, Tobias Benedikt. 2022. "Reception History and Early Chinese Classics" Religions 13, no. 12: 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13121224

APA StyleZürn, T. B. (2022). Reception History and Early Chinese Classics. Religions, 13(12), 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13121224