The Impact of Religion and Social Support on Self-Reported Happiness in Latin American Immigrants in Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Religion and Religious Coping Mechanisms

1.2. Social Support and Religious Community

1.3. Happiness

2. Method

2.1. Design

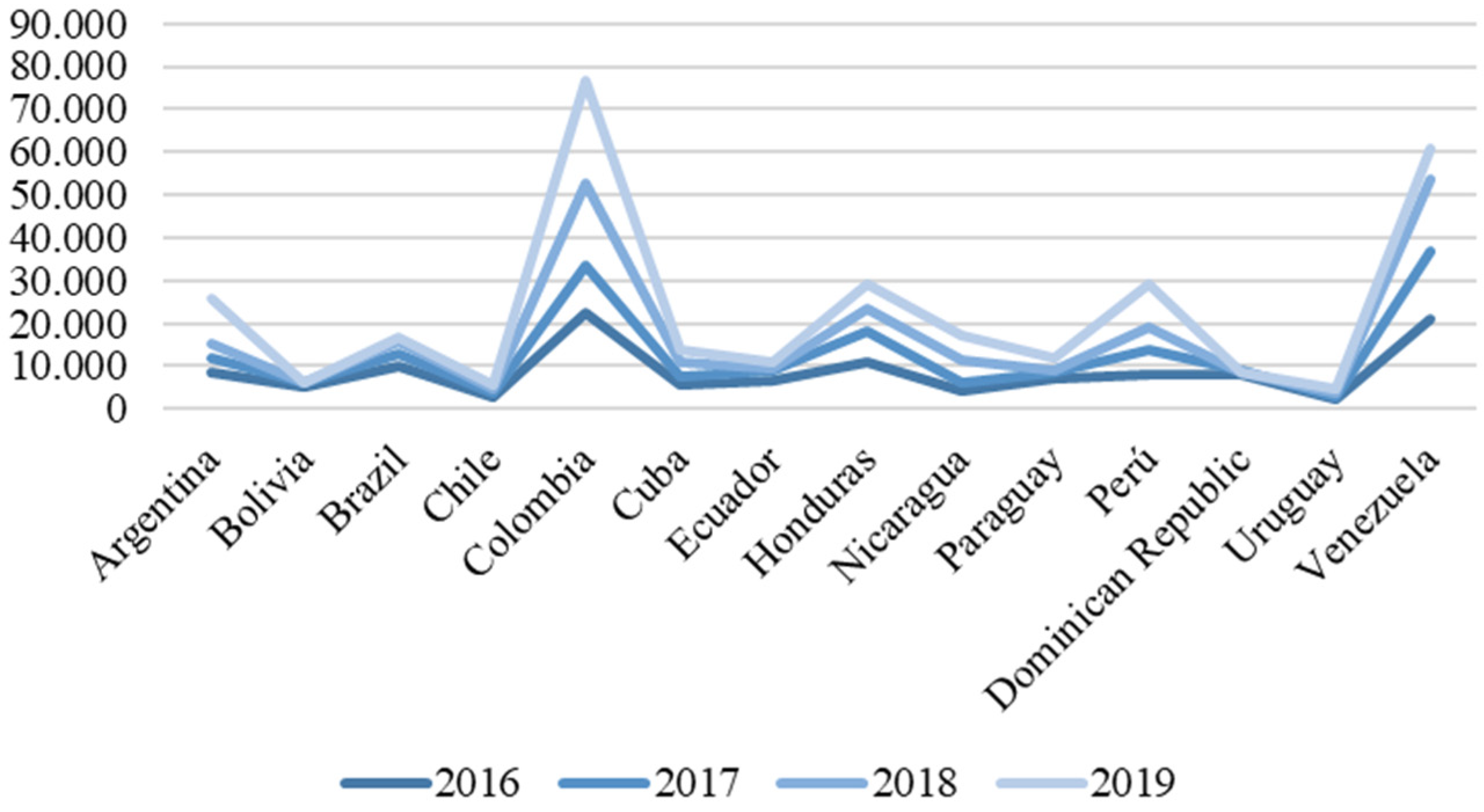

2.2. Sample

2.3. Variables and Instruments

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Variables

2.3.2. Social Support

2.3.3. Coping Mechanisms of Religious Origin

2.3.4. Religiosity

2.3.5. Acculturation

2.3.6. Subjective Happiness

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Data and Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. Correlations between Independent Variables and Happiness

3.3. Regression Models for Happiness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdel-Khalek, Ahmed M. 2006. Happiness, health, and religiosity: Significant relations. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 9: 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyle, Michael, Maryanne Martin, and Luo Lu. 1995. Testing for stress and happiness: The role of social and cognitive factors. In Stress and Emotion: Anxiety, Anger, and Curiosity, 15th ed. Edited by Charles Donald Spielberger, Irwin Sarason, John Brebner, Esther Greenglass, Pittu Laungani and Ann O’Roark. Washington, DC: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Basabe, Nekane, Zlovina Anna, and Paez Darío. 2004. Sociocultural Integration and Psychological Adaptation of Foreign Immigrants in the Basque Country. Basque Country: Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia. [Google Scholar]

- Buber, Martin. 1970. I and Thou, 1st ed. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Sociological Research. 2021. Consumer Confidence Index. Available online: http://www.cis.es/cis/export/sites/default/-Archivos/Marginales/3300_3319/3319/es3319mar.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2021).

- Cetrez, Önver A. 2011. The next generation of Assyrians in Sweden: Religiosity as a functioning system of meaning within the process of acculturation. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 14: 473–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Sheldon, Benjamin H. Gottlieb, and Lynn G. Underwood. 2000. Social relationships and health. In Social Support Measurement and Intervention: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists. Edited by Sheldon Cohen, Lynn Underwood and Benjamin Gottlieb. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, Phillip, and Matthias Koenig. 2013. Bridges and Barriers: Religion and Immigrant Occupational Attainment across Integration Contexts. International Migration Review 47: 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Diego, Rocío, and Manuel Guerrero. 2018. The influence of religiosity on health: The case of healthy/unhealthy habits. Culture of Care (Digital Edition) 22: 167–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Leslie, Ahto Elken, and Mandy Robbins. 2012. The affective dimension of religion and personal happiness among students in Estonia. Journal of Research on Christian Education 21: 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, Erich. 1950. Psychoanalysis and Religion. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- García, Manuel, Manuel Ramírez, and Isidro Jariego. 2001. The buffering effect of social support on depression in a group of immigrants. Psicothema 13: 605–10. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1966. Religion as a cultural system. In Anthropological Approaches to the Study of Religion. Edited by Michael Banton. London: Tavistock, pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Alcalá, Alejandro, Manuel Borboa-Osuna, and José Manuel Ornelas-Aguirre. 2021. Magical thinking, religiosity and bioethical decisions in medical students from Sonora. Journal Research in Medical Education 10: 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, José, Sandra Huenchuan, and Verónica Montes de Oca. 2003. Social support networks of the elderly: Conceptual Framework. Population Notes 29: 35–70. [Google Scholar]

- Headey, Bruce, Jürgen Schupp, Ingrid Tucci, and Gert Wagner. 2008. Authentic Happiness Theory Supported by Impact of Religion on Life Satisfaction: A Longitudinal Analysiswith Data for Germany. SOEP Papers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research 151: 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, Paul. 1959. Psychology of Religion. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Robert, and Toni Antonucci. 1980. Convoys over the life course: Attachment, roles, and social support. In Life-Span Develpment and Behavior. Edited by Paul Baltes and Orville Brim. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbaum, David, Lawrence Kupper, Azhar Nizam, and Eli Rosenberg. 2014. Applied Regression Analysis and Multivariable Methods. Boston: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Kloos, Bret, and Thom Moore. 2000. The prospect and purpose of locating community research and action in religious settings. Journal of Community Psychology 28: 119–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold, and Aarndt Büssing. 2010. The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): A five-item measure for use in epidemological studies. Religions 1: 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koenig, Harold, Dana King, and Verna Carson. 2012. Handbook of Religion and Health, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kouros, Theodoros, and Yiannis Papadakis. 2018. Religion, Immigration, and the Role of Context: The Impact of Immigration on Religiosity in the Republic of Cyprus. Journal of Religion in Europe 11: 321–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Nan. 1986. Conceptualizing social support. In Social Support, Life Events, and Depression. Edited by N. Lin, A. Dean and W. Ensel. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky, Sonja, and Heidi Lepper. 1999. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research 46: 137–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Nelda, and Valmi Sousa. 2011. Cross-Cultural Validation and Psychometric Evaluation of the Spanish Brief Religious Coping Scale (SBRCS). Journal of Transcultural Nursing: Official Journal of the Transcultural Nursing Society/Transcultural Nursing Society 22: 248–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molero, Fernando, Patricia Recio, Cristina García-Ael, María Fuster, and Pilar Sanjuán. 2013. Measuring Dimensions of Perceived Discrimination in Five Stigmatized Groups. Social Indicator Research 114: 901–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motiño, Alejandra, Jesús Saiz, Iván Sánchez-Iglesias, María Salazar, Tiffany Barsotti, Tamara Goldsby, Deepak Chopra, and Paul Mills. 2021. Cross-Cultural Analysis of Spiritual Bypass: A Comparison Between Spain and Honduras. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, David. 2008. Religion and Human Flourishing. In The Science of Subjective Well-Being. Edited by Michael Eid and Randy Lasen. New York: Guilford, pp. 323–43. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics INE. 2021. Flow of Immigration from Abroad by Year, Country of Origin and Nationality (Spanish/Foreign). Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=24295#!tabs-tabla (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Palomar, Joaquina, and Yessica Ivet Cienfuegos. 2007. Poverty and Social Support: A Comparative Study in Three Socioeconomic Levels. Interamerican Journal of Psychology 41: 177–88. [Google Scholar]

- Palomar, Joaquina, Graciela Matus, and Amparo Victorio. 2013. Development of a Social Support Scale (EAS) for adults. Universitas Psychologica 12: 129–37. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth. 1997. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth, Harold Koenig, and Lisa Pérez. 2000. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology 56: 519–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2018. The Age Gap in Religion around the World. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2018/06/ReligiousCommitment-FULL-WEB.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Reyes-Estrada, Marcos Rivera-Segarra, Eliut Ramos-Pibernus, Alíxida Rosario-Hernández, and Carmen L. Rivera-Medina. 2014. Development and validation of a scale to measure religiosity in a sample of adults in Puerto Rico. Puerto Rican Journal of Psychology 25: 226–42. [Google Scholar]

- Saiz, Jesús, Meredith Pung, Kathleen Wilson, Christopher Pruitt, Thomas Rutledge, Laura Redwine, Pam Taub, Barry Greenberg, and Paul Mills. 2020. Is Belonging to a Religious Organization Enough? Differences in Religious Affiliation Versus Self-Ratings of Spirituality on Behavioral and Psychological Variables in Individuals with Heart Failure. Healthcare 8: 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiz, Jesús, Berta Ausín, Clara González-Sanguino, Miguel Castellanos, María Salazar, Carolina Marin, Aída López-Gómez, Carolina Ugidos, and Manuel Muñoz. 2021a. Self-Compassion and Social Connectedness as Predictors of “Peace and Meaning” during Spain’s Initial COVID-19 Lockdown. Religions 12: 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz, Jesús, Xin Chen-Chen, and Paul Mills. 2021b. Religiosity and Spirituality in the Stages of Recovery From Persistent Mental Disorders. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 209: 106–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgado, Ana. 2014. Review of empirical studies on the impact of religion, religiosity and spirituality as protective factors. Purposes and Representations 2: 121–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- San Román, Silvia, Asunción Martínez, Félix Zurita, Ramón Chacón, Pilar Puertas, and Gabriel González. 2019. Resilience capacity according to religious tendency and gender in university students. Electronic Journal of Educational Research 21: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simsek, Müge, Frank van Tubergen, and Fenella Fleischmann. 2020. Religion and Intergroup Boundaries: Positive and Negative Ties Among Youth in Ethnically and Religiously Diverse School Classes in Western Europe. Review of Religious Research 5: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, Ruth. 1995. World Database of Happiness. Social Indicators Research 34: 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vera, Pablo, Karem Celis, and Natalia Córdova. 2011. Happiness evaluation: Psychometric analysis of the subjective happiness scale in the Chilean population. Psychological Therapy 29: 127–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vieten, Cassandra, and David Lukoff. 2021. Spiritual and Religious Competencies in Psychology. American Psychologist 5: 129–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenham, Clare, Julia Smith, and Rosemary Morgan. 2020. COVID-19: The Gendered Impacts of the Outbreak. The Lancet 395: 846–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wortmann, Jennifer. 2013. Religious Coping. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. Edited by Marc Gellman and Rick Turner. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Yoffe, Laura. 2012. Positive effects of religious/spiritual practices in grief. Advances in Psychology 20: 9–30. [Google Scholar]

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | N | % | % Accumulated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Feminine | 131 | 63.6 | 63.6 |

| Masculine | 75 | 36.4 | 100 | |

| Age category * | From 18 to 31 | 105 | 51 | 51 |

| From 32 to 45 | 45 | 21.8 | 72.8 | |

| From 46 to 59 | 40 | 19.4 | 92.2 | |

| From 60 to 74 | 16 | 7.8 | 100 | |

| Religious beliefs | Catholic Christian | 144 | 69.9 | 69.9 |

| Protestant Christian | 37 | 18 | 87.9 | |

| Other | 25 | 12.1 | 100 | |

| Group membership | No | 156 | 75.7 | 75.7 |

| Yes | 50 | 24.3 | 100 | |

| Membership group | None | 157 | 76.2 | 76.2 |

| Catholic group | 15 | 7.3 | 83.5 | |

| Protestant group | 34 | 16.5 | 100 | |

| Psychological Variables | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Social support | 3.68 (0.46) |

| Acculturation | 7.89 (1.58) |

| Happiness | 5.43 (1.09) |

| Religiosity | 15.80 (6.82) |

| Positive religious coping mechanisms | 1.80 (1.13) |

| Negative religious coping mechanism | 0.71 (0.88) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Happiness | 1 | ||||

| 2. Social support | 0.329 *** | ||||

| 3. Positive religious coping | 0.244 *** | −0.027 | |||

| 4. Negative religious coping | −0.206 ** | −0.233 ** | 0.169 * | ||

| 5. Religiosity | 0.392 *** | 0.009 | 0.789 *** | 0.034 | |

| 6. Acculturation | 0.095 | 0.118 | 0.126 | 0.031 | 0.039 |

| N | 206 | 206 | 206 | 206 | 206 |

| Models | Predictors | R2ADJ | B | SE | p | 95% CI | FIV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||||||

| 1 | Age | 0.014 | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.048 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 1.00 |

| 2 | Social Support | 0.104 | 0.787 | 0.154 | 0.000 | 0.484 | 1.09 | 1.00 |

| Age | 0.122 | 0.012 | 0.005 | 0.023 | 0.002 | 0.022 | 1.00 | |

| 3 | Religiosity | 0.149 | 0.067 | 0.010 | 0.000 | 0.048 | 0.086 | 1.03 |

| Social Support | 0.252 | 0.706 | 0.144 | 0.000 | 0.423 | 0.989 | 1.06 | |

| Negative Religious Coping | 0.271 | −0.164 | 0.076 | 0.031 | −0.313 | −0.015 | 1.08 | |

| Gender | 0.284 | 0.295 | 0.137 | 0.033 | 0.023 | 0.566 | 1.06 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Formoso-Suárez, A.M.; Saiz, J.; Chopra, D.; Mills, P.J. The Impact of Religion and Social Support on Self-Reported Happiness in Latin American Immigrants in Spain. Religions 2022, 13, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020122

Formoso-Suárez AM, Saiz J, Chopra D, Mills PJ. The Impact of Religion and Social Support on Self-Reported Happiness in Latin American Immigrants in Spain. Religions. 2022; 13(2):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020122

Chicago/Turabian StyleFormoso-Suárez, Angélica M., Jesús Saiz, Deepak Chopra, and Paul J. Mills. 2022. "The Impact of Religion and Social Support on Self-Reported Happiness in Latin American Immigrants in Spain" Religions 13, no. 2: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020122

APA StyleFormoso-Suárez, A. M., Saiz, J., Chopra, D., & Mills, P. J. (2022). The Impact of Religion and Social Support on Self-Reported Happiness in Latin American Immigrants in Spain. Religions, 13(2), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020122