Symbol Matters: A Sequential Mediation Model in Examining the Impact of Product Design with Buddhist Symbols on Charitable Donation Intentions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Individual Charitable Donation Behavior and Buddhism

2.2. Buddhist Symbols and Religiosity

2.3. Theory of Reasoned Action and Product Semantics

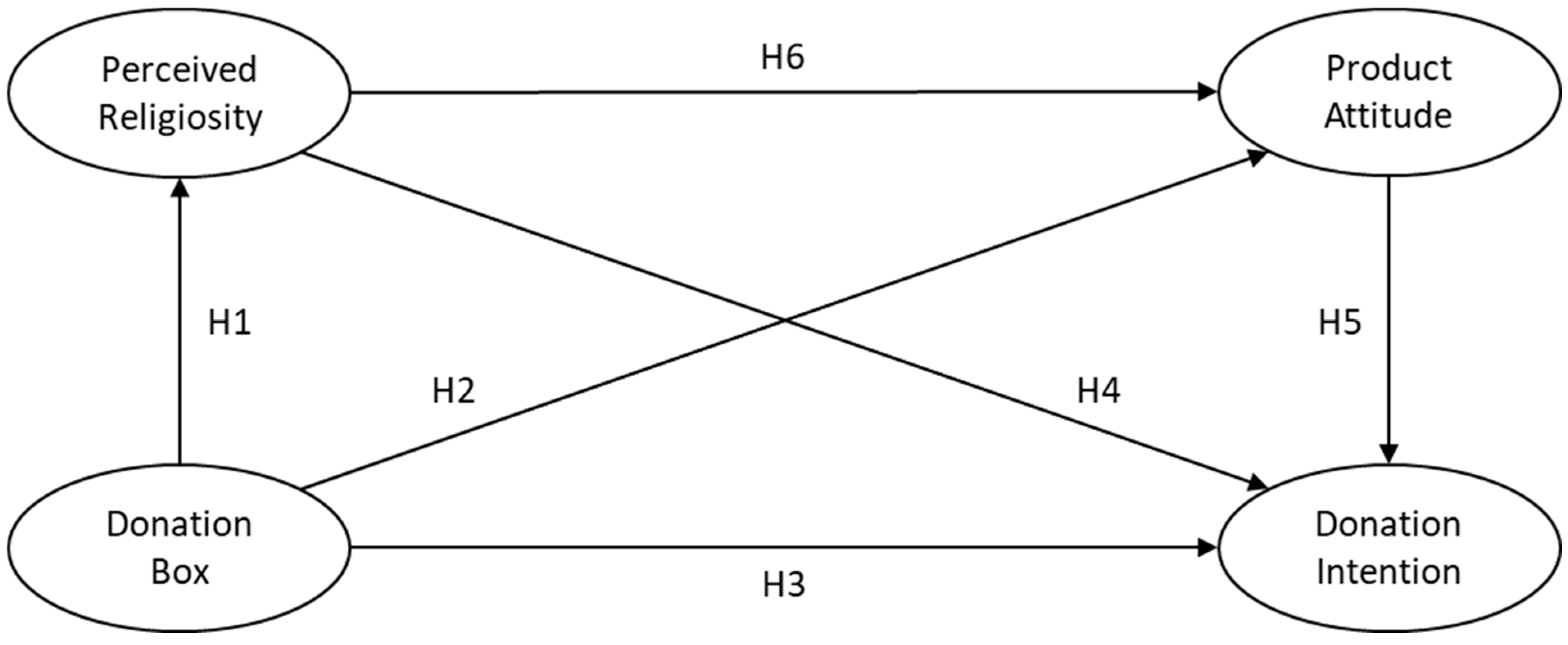

3. Hypotheses and Research Framework

4. Research Methods

4.1. Measurement Items

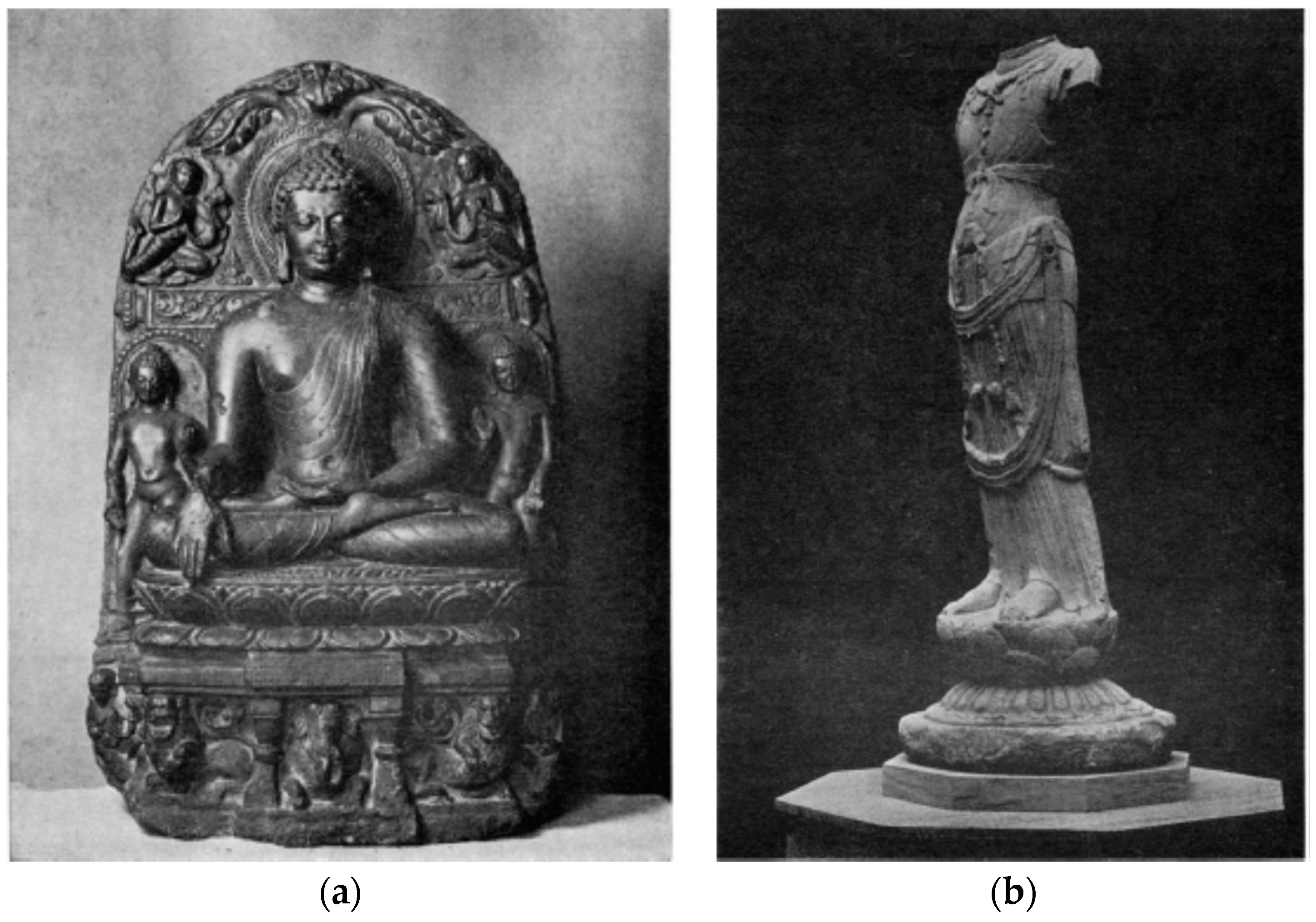

4.2. Stimuli and Pilot Study

4.3. Experiment Procedure

5. Results

6. Discussion, Limitation and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajzen, Icek. 1991. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50: 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, Denni, and Hari Lasmono. 2015. Are Religious People More Caring? Exploring the Impact of Religiosity on Charitable Organizations in a Developing Country. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 20: 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atkins, Charles, Joshua Dubler, Vincent Lloyd, and Mel Webb. 2019. Using the Language of Christian Love and Charity: What Liberal Religion Offers Higher Education in Prison. Religions 10: 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baring, Rito. 2018. Emerging Transitions in the Meaning of Religious Constructs: The Case of the Philippines. Religions 9: 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beer, Robert. 2003. The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Chicago: Serindia Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, Tatjana, and Mirabai Blau. 2003. Buddhist Symbols. New York: Sterling Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Blofeld, John Eaton Calthorpe. 2009. Bodhisattva of Compassion: The Mystical Tradition of Kuan Yin. Boston: Shambhala Publications. [Google Scholar]

- BuddhaNet. 2015. Buddhist Statistics: Top 10 Buddhist Countries, Largest Buddhist Populations. Available online: http://www.buddhanet.net/e-learning/history/bstatt10.html (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Cao, Xiaoxia. 2016. Framing Charitable Appeals: The Effect of Message Framing and Perceived Susceptibility to the Negative Consequences of Inaction on Donation Intention. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 21: 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center Pew Research. 2012. Religion & Public Life: Buddhists. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2012/12/18/global-religious-landscape-exec/ (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Chamberlayne, John Hampden. 1962. The Development of Kuan Yin: Chinese Goddess of Mercy. Numen 9: 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Man Kit. 1998. Predicting Unethical Behavior: A Comparison of the Theory of Reasoned Action and the Theory of Planned Behavior Man Kit Chang. Journal of Business Ethics 17: 1825–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clobert, Magali, Vassilis Saroglou, and Kwang Kuo Hwang. 2015. Buddhist Concepts as Implicitly Reducing Prejudice and Increasing Prosociality. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 41: 513–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. 1935. Angel and Titan: An Essay in Vedic Ontology. Journal of the American Oriental Society 55: 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelis, Reed, Gabriel Acevedo, and Xiaohe Xu. 2016. Secular Volunteerism among Texan Emerging Adults: Exploring Pathways of Childhood and Adulthood Religiosity. Religions 7: 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dotson, Michael J., and Eva M. Hyatt. 2002. Religious Symbols as Peripheral Cues in Advertising. Journal of Business Research 48: 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, Martin, and Icek Ajzen. 2011. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ghori, Ahmer K., and Kevin C. Chung. 2007. Interpretation of Hand Signs in Buddhist Art. Journal of Hand Surgery 32: 918–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallman, Ralph J. 2006. The Art Object in Hindu Aesthetics. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 12: 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Heesup, Li Tzang (Jane) Hsu, and Chwen Sheu. 2010. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Green Hotel Choice: Testing the Effect of Environmental Friendly Activities. Tourism Management 31: 325–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, Peter (Brian Peter). 2013. An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2015. An Index and Test of Linear Moderated Mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research 50: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henley, Walter Hodges, Jr., Melodie Philhours, Sampath Kumar Ranganathan, and Alan J. Bush. 2009. The Effects of Symbol Product Relevance and Religiosity on Consumer Perceptions of Christian Symbols in Advertising. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 31: 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Peter C., and Ralph W. Hood. 1999. Measures of Religiosity. Birmingham: Religious Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, Christopher D., Kevin J. Shanahan, and Mary Anne Raymond. 2014. The Moderating Role of Religiosity on Nonprofit Advertising. Journal of Business Research 67: 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Daniel J., and Charles Gengler. 2001. Emotional Contagion Effects on Product Attitudes. Journal of Consumer Research 28: 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Wei. 2010. The Principles and Methods of Applying Buddhism Graphical Symbols in Modern Design. Art Panorama 9: 114–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kashif, Muhammad, Syamsulang Sarifuddin, and Azizah Hassan. 2015. Charity Donation: Intentions and Behavior. Marketing Intelligence and Planning 33: 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 1984. Product Semantics: Exploring the Symbolic Qualities of Form. Spring 3: 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Yu-Kang, and Chun-Tuan Chang. 2009. Who Gives What to Charity? Characteristics Affecting Donation Behavior. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 35: 1173–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Fan. 2007. Shaping the Lotus Sutra: Buddhist Visual Culture in Medieval China—By Eugene Y. Wang. Religious Studies Review 33: 332–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, Chung-Mau. 2012. Deceased Donation in Asia: Challenges and Opportunities. Liver Transpl 18: 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Jeffery. 2019. Religious Experience, Hindu Pluralism, and Hope: Anubhava in the Tradition of Sri Ramakrishna. Religions 10: 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lumpkins, Crystal Y. 2010. Sacred Symbols as a Peripheral Cue in Health Advertisements: An Assessment of Using Religion to Appeal to African American Women about Breast Cancer Screening. Journal of Media and Religion 9: 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macías Ruano, Antonio José, José Ramos Pires Manso, Jaime de Pablo Valenciano, and María Esther Marruecos Rumí. 2020. The Misericórdias as Social Economy Entities in Portugal and Spain. Religions 11: 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marketplace. 2011. Buddhist Stuff & Prayer Animation V 2.0. Available online: https://marketplace.secondlife.com/p/Buddhist-Stuff-Prayer-Animation-V-10/2829630?preview=true (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Martin, Richard, and John Randal. 2008. How Is Donation Behaviour Affected by the Donations of Others? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 67: 228–38. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Tracy. 2015. Of Palaces and Pagodas: Palatial Symbolism in the Buddhist Architecture of Early Medieval China. Frontiers of History in China 10: 222–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Andrew A., and Jerry C. Olson. 1981. Are Product Attribute Beliefs the Only Mediator of Advertising Effects on Brand Attitude? Journal of Marketing Research 18: 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, Sidharth, Carrie La Ferle, and Sanjukta Pookulangara. 2018. Studying the Impact of Religious Symbols on Domestic Violence Prevention in India: Applying the Theory of Reasoned Action to Bystanders’ Reporting Intentions. International Journal of Advertising 37: 609–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, A., and E. Tamam. 2012. Impact of Islamic Religious Symbol In Producing Favorable Attitude Toward Advertisement. Revista de Administratie Publica si Politici Sociale 1: 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Nonprofits Source. 2018. Charitable Giving Statistics. Available online: https://nonprofitssource.com/online-giving-statistics/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Pace, Stefano. 2013. Does Religion Affect the Materialism of Consumers? An Empirical Investigation of Buddhist Ethics and the Resistance of the Self. Journal of Business Ethics 112: 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Jerry Z., and Joseph Baker. 2007. What Would Jesus Buy: American Consumption of Religious and Spiritual Material Goods. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 46: 501–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, Sampath Kumar, and Walter H. Henley. 2008. Determinants of Charitable Donation Intentions: A Structural Equation Model. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 13: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, Adrian. 1999. Charitable Giving: Towards a Model of Donor Behaviour. Journal of Marketing Management 15: 215–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saritoprak, Seyma N., Julie J. Exline, and Nick Stauner. 2018. Spiritual Jihad among U.S. Muslims: Preliminary Measurement and Associations with Well-Being and Growth. Religions 9: 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saroglou, Vassilis, and Antonio Muñoz-García. 2008. Individual Differences in Religion and Spirituality: An Issue of Personality Traits and/or Values. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47: 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, Blair H., Jon Hartwick, and Paul R. Warshaw. 2002. The Theory of Reasoned Action: A Meta-Analysis of Past Research with Recommendations for Modifications and Future Research. Journal of Consumer Research 15: 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snellgrove, David. 1956. Buddhist Morality. The Downside Review 74: 234–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Valerie A., Diane Halstead, and Paula J. Haynes. 2010. Consumer Responses to Christian Religious Symbols in Advertising. Journal of Advertising 39: 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillich, Paul. 1958. The Religious Symbol. Symbolism in Religion and Literature 87: 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, Shu Pei. 2021. Charity Organizations Adopting Virtual Reality Modality: Theorization and Validation. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce 31: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cappellen, Patty, and Vassilis Saroglou. 2012. Awe Activates Religious and Spiritual Feelings and Behavioral Intentions. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 4: 223–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Xiuhua, and Sung Joon Jang. 2018. The Effects of Provincial and Individual Religiosity on Deviance in China: A Multilevel Modeling Test of the Moral Community Thesis. Religions 9: 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ward, William E. 1952. The Lotus Symbol: Its Meaning in Buddhist Art and Philosophy. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 11: 135–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, Gary R., and Bradley R. Agle. 2002. Religiosity and Ethical Behavior in Organizations: A Symbolic Interactionist Perspective. Academy of Management Review 27: 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Zhiqi, and Lan Ming. 2015. Buddhist Tourism Product Design Based on Zen Culture. Arts Exploration 29: 112–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Sung. 2018. Interaction Effects of Religiosity Level on the Relationship between Religion and Willingness to Donate Organs. Religions 10: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Mediation | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buddhist Symbol -> Perceived Religiosity -> Donation Intention | 0.049 | 0.060 | −0.066 | 0.183 |

| Buddhist Symbol -> Product Attitude -> Donation Intention | 0.906 | 0.206 | 0.533 | 1.342 |

| Buddhist Symbol -> Religiosity -> Attitude -> Donation Intention | 0.132 | 0.086 | 0.004 | 0.336 |

| Total Indirect Effect | 1.088 | 0.236 | 0.648 | 1.567 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qin, Z.; Song, Y. Symbol Matters: A Sequential Mediation Model in Examining the Impact of Product Design with Buddhist Symbols on Charitable Donation Intentions. Religions 2022, 13, 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020151

Qin Z, Song Y. Symbol Matters: A Sequential Mediation Model in Examining the Impact of Product Design with Buddhist Symbols on Charitable Donation Intentions. Religions. 2022; 13(2):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020151

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Zhenzhen, and Yao Song. 2022. "Symbol Matters: A Sequential Mediation Model in Examining the Impact of Product Design with Buddhist Symbols on Charitable Donation Intentions" Religions 13, no. 2: 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020151

APA StyleQin, Z., & Song, Y. (2022). Symbol Matters: A Sequential Mediation Model in Examining the Impact of Product Design with Buddhist Symbols on Charitable Donation Intentions. Religions, 13(2), 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020151