Abstract

Identity is built in the context of an individual’s professed values, moral principles, and often, religiosity. Adolescence and emerging and early adulthood are times of intensive identity construction and of changes in religious attitudes. Therefore, the aim of this study was to characterise people across these three developmental periods in terms of the level of their identity and religiosity, and to examine whether particular identity styles allow for the prediction of the overall level of religiosity. For this purpose, the whole sample of N = 1017 individuals and particularly from adolescence (n = 307), emerging adulthood (n = 410), and early adulthood (n = 302) were studied. The results showed a lower level of the informational style and a higher level of the diffuse-avoidant style in adolescence as compared with the two older groups, who did not differ from each other. The overall level of religiosity did not significantly differentiate the developmental groups; however, it was explained by identity formation styles in different ways at particular developmental stages. Results of moderation analyses suggest that the informational style has positive effect only in adolescence; the normative style has positive effects in each age group but is strongest in early adulthood, and the diffuse-avoidant style presents negative effect in adolescence.

1. Introduction

One of the main developmental tasks young people face is to answer questions about who they are, where they are going, and what the meaning of their life is. The answers to these questions are usually referred to as one’s identity. Traditionally, the task of identity formation takes place during adolescence (Erikson 1964), but today, the process of identity formation is prolonged, falling mainly in the period of emerging adulthood (Arnett 2000), and even taking place in adulthood (Fadjukoff et al. 2007). One way that young people form their self-concept is through reflecting on their worldview in the area of religiosity. The present study examined the diversity of identity styles and types of religiosity from adolescence to early adulthood and the relation between identity styles and religiosity. In particular, the main aim of the research was to examine whether the intensity of each identity style (Berzonsky 1989) can predict the religiosity from adolescence to early adulthood.

1.1. Changes in Identity from Adolescence to Adulthood

According to Arnett (2000), socio-economic changes have resulted in the postponement of identity commitments, which now occur mainly in the phase of emerging adulthood and in later life. During the different phases of youth, people may shape their own identity in different ways (Marcia 1966; Berzonsky 1989). Erikson’s concept of identity has gained various operationalisations, the earliest of which was proposed by Marcia (1966). Marcia distinguished four identity statuses—achievement, moratorium, foreclosure, and diffusion—based on the presence or lack of identity exploration and identity commitment. Berzonsky (1989) described identity in a more dynamic way, characterising it not only as a structure, but also as a process occurring as different styles (Berzonsky 2003, 2004). An identity style refers to the strategies people use to construct knowledge about themselves (i.e., build an identity) and defines the role said knowledge plays in making life decisions (Berzonsky and Ferrari 1996). The author distinguishes three identity styles (identity processing orientations): informational, normative, and diffuse-avoidant. Individuals with an informational style make efforts to independently seek, process, and evaluate information related to their self-concept and incorporate it into their structure of self. Individuals with a normative style more automatically internalise knowledge about themselves and conform to the expectations of significant others. Perceiving a discrepancy between the self-image and the desired standards arouses feelings of guilt in them. The diffuse-avoidant style involves postponing and avoiding conflicts and deferring decisions as long as possible, and is used by people who do not have coherent beliefs about themselves, and their actions are mainly situationally determined (Berzonsky 2004). According to Berzonsky, from late adolescence onwards, most individuals have the ability to use strategies that correspond to all the three identity styles (Berzonsky 1990).

Based on a meta-analysis of dozens of findings of longitudinal and cross-sectional studies, Kroger and Marcia (2011) identified several trends of change in the area of identity statuses from adolescence to emerging adulthood. The main direction of change is from identity diffusion and foreclosure, through moratorium, to identity achievement. During adolescence, there are significant changes in the frequency of the identity diffusion (diffuse-avoidant style) and identity achievement (informational style) statuses. Namely, there is a decrease in the frequency of identity diffusion (diffuse-avoidant style) while there is an increase in the frequency of achieved identity (informational style). With regard to the status of moratorium and foreclosure identity (normative style), no significant changes are observed (Waterman 1982; Czyżowska and Mikołajewska 2014; Gurba 2013).

Academic environments provide students with opportunities to gain new experiences and develop career goals (Berzonsky and Kuk 2000; Kroger et al. 2010; Tanner 2006). This may be the cause of the intensive and relatively similar identity development of students at different universities during the four-year period between the first and the last year of study (Waterman et al. 1974; Waterman and Goldman 1976; Cramer 2017). Study results indicate that in the area of professional plans, there was an increase in the frequency of the achieved identity status and a decrease in the frequency of the moratorium status; in the area of religious worldview, the foreclosure identity status was less frequent in the eldest students. At the same time, during the study period, the statuses of achieved identity and foreclosure identity in relation to professional plans were the most stable compared with the other domains, and diffusion identity was the most stable in the area of religiosity compared with the area of political ideology and professional plans (Waterman and Goldman 1976). As young people complete their education and enter the workforce, they explore less intensively and instead engage in building identity commitments in different areas of activity. However, leaving the family home or starting one’s own family is also important for young people’s identity formation (Guerreiro et al. 2004; Jordyn and Byrd 2003; Fadjukoff et al. 2007) and is related to an increase in the achieved identity status (around the age of 27). In Western cultures, the achieved identity status is tantamount to a manifestation of mature identity. It is worth noting that although identity begins to form during adolescence, fewer than half of young people fail to achieve this identity status by early adulthood in areas such as family, professional activity, or worldview (Cramer 1998; Kroger 2007). However, according to a meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies, between the ages of 17 and 36, there is a steady increase in the average proportion of individuals with the achieved identity status, with stability in the number of respondents with the foreclosure identity status, and a decrease, but only between the ages of 30 and 36, in the proportion of adults with the identity diffusion status (Kroger et al. 2010). Although developmental trends in identity formation are quite complex, it is thought that most identity changes occur by the end of early adulthood (Lichtwarck-Aschoff et al. 2008; Cramer 2017).

1.2. Religiosity of Adolescents, Individuals in Emerging Adulthood, and Young Adults

In the period from adolescence to early adulthood there are significant changes in the ways a person approaches God or Transcendence, as well as in the forms of participation in religious worship. We define religiosity here as a person’s subjective, individual attitude to God expressed in the sphere of concepts, beliefs, feelings, and such a person’s behaviours related to worship, which takes institutionalised and organised forms (Miller and Thoresen 2003). In our research, we rely on the concept of Huber (2003, 2007), who describes religiosity in terms of Kelly’s personal constructs (Zarzycka 2011). The position of religious constructs in relation to other personal constructs in the personality structure determines the type of a person’s religiosity: a central position manifests intrinsic religiosity; a position subordinate to other personal constructs indicates heteronomous religiosity; a marginal position of the constructs indicates a lack of interest in religious issues.

Religiosity in individual development, as in other psychological spheres, is shaped in a specific context of one’s life and activity; initially, it is shaped mainly by the child’s relationship with their parents, later in the peer environment, with groups linked to the institution of the Church, as well as in the context of the young person’s intimate relationships. Adolescence is a time of significant developmental changes in the religious experience, a time when the young person transforms their religious attitudes and “makes them his or her own personality equipment” (Allport [1967] 1988, p. 120), which means developing a personal attitude towards religion and religious matters. Initially, adolescents experience religiosity in terms of duty, obligation, and obedience by appealing to authority figures and relying on family traditions, especially with regard to participation in religious rites (Desmond et al. 2010; Czyżowska and Mikołajewska 2014). In subsequent years, along with the development of formal operational thinking and a fuller understanding of abstract concepts, they develop a deeper understanding of the religion in which they grew up, and those with a strong desire to achieve autonomy in the area of religious beliefs and practices often embark on exploring alternative ideologies (Stolz et al. 2013) while at the same time revealing rebellious behaviours towards the family tradition and authority figures in the Church. According to Fowler (1981), due to increased criticism and a lack of mature reflection, adolescents are saturated with feelings and emergent, sometimes contradictory meanings. Their faith represents mainly the synthetic–conventional faith stage. During this stage, a “person has an ‘ideology’, a more or less consistent clustering of values and beliefs, but he or she has not objectified it for examination and in a sense is unaware of having it” (p. 173). An increasing independence from the environment often involves experiencing religious crises (Regnerus 2003) and a decline in religiosity (Uecker et al. 2007; Petts 2009). Especially from early to middle adolescence, the frequency of participation in religious services decreases (Desmond et al. 2010; Hayward and Krause 2013; Petts 2009; Uecker et al. 2007). It should be noted that significant variation in religiosity is observed among adolescents, while their overall level of religiosity decreases only slightly (Desmond et al. 2010; Pearce and Denton 2011). According to a study by Regnerus and Uecker (2006), a third of individuals reveal a stable pattern of religious participation from mid-adolescence to emerging adulthood. In the period of emerging adulthood, young people who had so far been religiously committed to a small degree, become less committed to their religious practices under the influence of their changing living conditions and the environment, and their religiosity grows weaker. On the other hand, those for whom faith is an important aspect of their lives engage more than before in individualised religious activities, such as prayer or meditation, and participate in various forms of religious worship on a regular basis (McNamara Barry et al. 2010). The reduction of parental influence, which most often occurs when a young person starts university, and the experience of worldview pluralism by new contacts with non-religious peers or members of other religions may contribute to an independent search for worldview beliefs. This is accompanied by a focus on the inner aspects of beliefs and experiences with a simultaneous departure from religious practices, particularly when these had been enforced by obedience to authority figures (Uecker et al. 2007; Dew et al. 2020). Individuate–reflective faith is then formed (Fowler 1981) and an internal religious orientation emerges. Research findings indicate that the religious beliefs remain stable or grow stronger during emerging adulthood (18–25 years; Lefkowitz 2005), while activity related to religious practices simultaneously decreases (Koenig et al. 2008; Uecker et al. 2007).

In early adulthood, in the sphere of religiosity, as in other areas of development, there is a great interindividual differentiation. Generally, the period of early adulthood is a time of religious stability and growing religiosity, although many young people also distance themselves from the Church. The increase in religiosity among people between the ages of 25 and 40 means that their faith becomes more stable and personal (consistence). This is characterised by a private relationship with God (intimacy), accompanied by feelings of anxiety and anger (Sullivan 2012; Pearce and Denton 2011; Ellison and Henderson 2011). According to Fowler (1981), young adults are characterized by a conjunctive faith, which means that they are capable of discovering other religions and beliefs systems in such a way that their own views can be either reinforced or amended.

1.3. Relation between Young People’s Identity and Religiosity

Research on relations between identity and religiosity usually take place during adolescence when young people begin to construct their identities (King 2003). There is much less exploration of these relations in subsequent developmental periods, (i.e., emerging adulthood and early adulthood), when identities are stabilised while the type of religiosity may change. The existing literature does not provide consistent results on the relations between identity and religiosity. This paper attempts to fill this gap by presenting the results of our research on the relation between identity styles and religiosity in the three developmental periods: adolescence, emerging adulthood, and early adulthood.

According to some researchers (Erikson 1964, 1968; Arnett 2010), religious beliefs and the values resulting from these beliefs allow adolescents, as well as people on the threshold of adulthood, to understand the meaning of the world and of their own life.

The results of empirical studies on the relation between the characteristics of identity and religiosity of young people do not provide consistent results. On the one hand, identity commitment co-occurs with high levels of religiosity (Watson et al. 1998; Markstrom-Adams 1999); individuals in the identity diffusion and moratorium statuses are characterised by religious immaturity (Markstrom-Adams and Smith 1996; Duriez et al. 2004; Gebelt et al. 2009; Leak 2009; Puffer et al. 2008); adolescents with a normative style are more religious than those with other identity styles, and adolescents with a dominant informational identity style comprehend religious content in a personal and symbolic way (Duriez et al. 2004). On the other hand, some research does not find a correlation between identity dimensions and indicators of religious maturity (Parker 1985; Markstrom-Adams 1999; Puffer et al. 2008), and others report lower levels of religious orientation in adolescents with a mature identity (achieved identity) compared to peers in the identity diffusion status (Foster and Laforce 1999).

The sources of the aforementioned inconsistencies include significant variation in both the theoretical approaches and the tools used in the research on identity and religiosity, as well as the fact that these relations were tested in different phases of adolescence. Therefore, our own research into the relationships between identity styles and the type of religiosity in young people was conducted for separate developmental periods, from adolescence and through emerging adulthood to early adulthood, looking for the contribution of each identity style in the shaping of the level of religiosity in young people.

In the literature, there are only a few studies that focus on the significance of selected identity styles for the level of religiosity of people in adolescence, emerging adulthood, and early adulthood. Longitudinal studies reported by Duriez et al. (2008) show that the normative style directly influences selected dimensions of religiosity, and the informational and diffuse-avoidant styles do so indirectly through identity commitment. The direct relevance of the informational identity style to religiosity was also reported in a study of American youth (Grajales and Sommers 2016). The correlation between the level of religiosity and the identity style was also found in students who follow Islam; the normative style was a positive, and the diffuse-avoidant style was a negative predictor of their level of religiosity. It has also been shown that identity styles can mediate between personality traits and dimensions of young people’s religiosity (Duriez and Soenens 2006). The aforementioned research findings allow us to expect that young people’s religiosity can be predicted based on their identity styles. From the theoretical perspective, as identity has a regulatory function in human life, the identity style determines the activity of the individual in different areas of life, and therefore, also in the area of religious beliefs and attitudes.

1.4. Research Problem

Based on existing research findings on the characteristics of identity styles and changes in young people’s religiosity, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypotheses 1 (H1).

The level of normative identity style does not differentiate the distinguished age groups, as indicated by the findings of the research conducted from the perspective of both styles and statuses of identity (Kroger and Marcia 2011).

Hypotheses 2 (H2).

Adolescents are characterised by the highest intensity of the diffuse-avoidant style and the highest intensity of the informational identity style, as compared with people in emerging and early adulthood.

Teenagers, in general, experience a kind of identity confusion; despite signs of reaching biological maturity, they do not receive the privileges associated with adulthood, and at the same time the environment places greater demands on them. Abrupt biological changes, strong emotionality, and the need for acceptance in the peer environment may foster reactive and conformist behaviours, which is characteristic of people with the diffuse-avoidant style. Cognitive development and the broadening of individual experiences in the spheres of professional activity, social relations, and worldview are conducive to the processes of constructing one’s own identity in the periods of emerging adulthood and early adulthood (Kroger and Marcia 2011). If young people develop critical thinking from the use of formal operational structures and postformal thought, then it can be expected that there will be a higher intensity of the informational style of identity in the “older” groups of respondents, compared with the group of adolescents. Analytical thinkers, as opposed to intuitive thinkers, critically evaluate the knowledge provided by authority figures and incorporate both congruent and incongruent information into their self-concept. Informational style is positively associated with mentally effortful rational processing, decisional vigilance, experiential openness, and problem-focused coping (Berzonsky 2004).

Hypotheses 3 (H3).

Due to the large interindividual variation in the level of religiosity during the periods of both emerging adulthood and early adulthood (Stolzenberg et al. 1995), it is difficult to formulate an unambiguous hypothesis regarding the level of religiosity in the three developmental groups. However, an analysis of developmental patterns combined with previous research allows us to expect that adolescents and people in emerging adulthood, who are rebelling against authorities while searching for their own life paths, will report lower levels of religiosity compared to adults who are presumably experiencing important life events that, in Polish society, are usually associated with religiosity and the Church (e.g., marriage or christening of a child; Stolzenberg et al. 1995; Sullivan 2012).

Hypotheses 4 (H4).

Depending on the developmental period (adolescence, emerging adulthood, or early adulthood), identity processing styles may be differentially related to the level of religiosity (Duriez and Soenens 2006).

Hypotheses 4a (H4a).

The informational identity style is a predictor of the level of religiosity primarily during adolescence. To an adolescent searching for purpose and meaning in life, religion offers definitive answers and provides a perspective for solving important life problems. Therefore, in adolescence, a young person may concentrate on exploring the sphere related to faith and religiosity, which consequently promotes their development in this sphere. In subsequent developmental periods, however, intensive exploration will also concern other spheres of activity, such as professional and social relations, and especially intimate relationships (Arnett 2000). These spheres may be perceived as more important than the formation of a religious worldview due to the developmental tasks related to adulthood.

Hypotheses 4b (H4b).

Normative identity style is a predictor of the level of religiosity in each of the three developmental periods.

Faith and religiosity are based on trust in authorities that are important in this sphere, and a significant role is played by participation in worship (this dimension describes religiosity in the Huber scale we used). Thus, the normative identity style, which describes people who construct self-concepts based on the models derived from their authorities, may foster—especially in Polish society, which is high on traditional Catholicism—the development of this aspect of religiosity, which consists in adopting and using ready-made models of professing faith (Duriez et al. 2008).

Hypotheses 4c (H4c).

Having a diffuse-avoidant style of identity means avoiding important life issues due to the lack of a stable system of values and beliefs (including religious ones), which generally would provide the basis for one’s decision-making. Therefore, it can be assumed that by removing the religious sphere from the area of main interests and commitments, the diffuse-avoidant style of identity will suppress this religiosity, especially in adolescents. Therefore, we assume that in later periods (emerging adulthood and early adulthood), religiosity and worldview issues are less important in the process of identity construction as compared to the social relations and professional activity spheres. As a result, we expect that the diffuse-avoidant identity style will not be a significant predictor of religiosity in the older developmental groups.

The relations formulated in Hypothesis 4, which concern the identification of individual identity styles as predictors of religiosity depending on the developmental period (adolescence, emerging adulthood, and early adulthood), have not been previously examined. The current study allows us to compare the significance of identity styles for religiosity in the aforementioned phases of life.

2. Method and Materials

2.1. Study Group and Procedure

The study was conducted with N = 1017 individuals from different developmental periods: adolescence, emerging adulthood, and early adulthood. Group sizes are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample.

The participants in adolescence were pupils of five secondary schools located in Krakow and in a small towns around Krakow. In the beginning, we obtained permission to conduct research in these schools. Adolescents were studied in groups during school hours (parental consent was obtained beforehand). Older respondents who represented the period of emerging adulthood and early adulthood were individually recruited by psychology students using the snowball method. The student participants represented a variety of majors and the remaining participants had at least a high school education. The study was conducted individually. All the participants were of Polish origin.

2.2. Measures

The Identity Style Inventory (ISI-3; Berzonsky 1992) consists of three scales representing the identity styles: informational, normative, and diffuse-avoidant. The ISI-3 includes 40 items that describe beliefs and ways of coping with various issues. The respondent gives answers on a scale from 1 (definitely does not apply to me) to 5 (definitely applies to me). In the Polish studies, the Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient ranged from 0.61 to 0.81 (Senejko 2010), indicating a satisfactory reliability of the scales.

The Centrality of Religiosity Scale by R. Huber (C-15) (Huber 2003) is used to determine the centrality of religiosity (i.e., the degree of importance of religious constructs for the individual), and to characterise the level of religiosity in five dimensions: (1) interest in religious issues, indicating cognitive involvement in the elaboration of religious content; (2) religious experience, determining how often Transcendence is present in the person’s everyday experience; (3) prayer, illustrating the frequency of making contacts with a transcendental reality and the subjective importance of a personal contact with transcendence; (4) the level of religious beliefs, indicating the degree of certainty of the subjects about the existence of a transcendental reality; (5) worship, a dimension that indicates the frequency and subjective importance of participation in religious services. The current study also uses an overall index of the centrality of religiosity, which is the average of all aspects. In previous Polish studies, the Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient ranged from 0.82 to 0.93 (Zarzycka 2007).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the variables studied in each of the three groups.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for Identity Styles and Religiosity.

The values of skewness and kurtosis for all four variables tested (informational style, normative style, diffuse-avoidant style, and overall level of religiosity) in each age group are within the range <−1;1>, indicating a distribution of results close to normal. Firstly, we examined the differences in identity formation styles and religiosity between three developmental periods. Levene’s test indicated that the variances were homogeneous only for the diffuse-avoidant style. Due to the lack of homogeneity of variances, additional robust tests of equality of means were performed. The results for the robust tests were identical to the results of the analysis of variance, so the ANOVA results are presented here. The analyses indicate that the age groups differ in terms of the informational style F (2, 1014) = 6.45; p < 0.01, and the diffusion-avoidance style F (2, 1014) = 13.64; p < 0.001. Any differences in the normative style F (2, 1014) = 2.57; p > 0.05 and overall level of religiosity F (2, 1014) = 2.05; p > 0.05 are statistically insignificant. Secondly, a Games–Howell post hoc test was performed. These results indicate that, in adolescence, there is a significantly lower intensity of the informational style and a significantly higher intensity of the diffuse-avoidant style than in the other two older groups, which do not differ from each other.

3.2. Differences in Relations between Identity and Religiosity in Particular Developmental Periods

In order to test whether the relation between identity style and religiosity depends on the developmental period, a moderation analysis was carried out using the PROCESS macro version 3.4, released 12 August 2019 (Hayes 2018). The dependent variable was the overall level of religiosity; the independent variable was one identity style; the moderator was the developmental period; the control variables were the other two identity styles and gender. In a moderation analysis, a regression equation is built where the dependent variable is explained by all the variables included in the model and the interaction effect between the predictor and the moderator. In the case of a categorical moderator, k−1 interaction effects are calculated (two interaction effects in the case studied). The interaction effects were coded using the indicator method; the reference group was adolescence (Hayes and Montoya 2017). The results of the moderation analyses are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of the moderation analyses with religiosity as dependent variable.

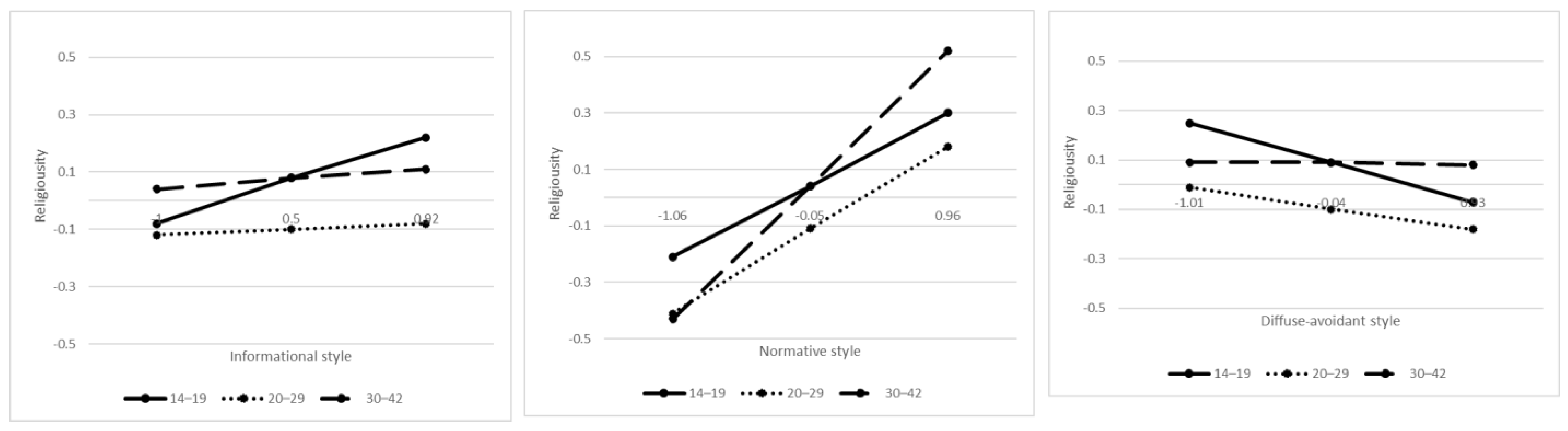

The results suggest that the developmental period moderates the relation between each style of identity formation and the overall level of religiosity while controlling for the other two styles and gender. While the interaction effect significantly (although very slightly) increases the level of the explained variance (R2 change) in the normative style model, for the informational style model, the significance of the R2 change is at the level of statistical tendency. The R2 change in the diffuse-avoidant style model is non-significant (p < 0.12). Based on the rules of moderation analysis with multicategorical variables (Hayes and Montoya 2017), the significance of the interaction effects means that the overall level of religiosity is explained by the informational style differently in emerging adulthood in comparison to adolescence, and by the normative and diffuse-avoidant styles in the early adulthood group differently than in adolescence. The exact level of the conditional effects of the explanatory variable on the dependent variable (coefficients from the regression analysis) across the age groups has been shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Effects of the explanatory variable (identity formation styles) on the dependent variable (overall level of religiosity) in each developmental period, as calculated using regression equations in 3 separate moderation analyses.

The moderation analyses, in which the three styles of identity formation and gender were included in the models, indicate that identity styles predict the overall level of religiosity differently in the distinguished developmental periods. In the case of the informational style, the conditional effect is positive only in the youngest age group. For the normative style, the effect is positive and significant in each age group, but is strongest in the oldest age group. For the diffuse-avoidant style, the effect is negative and significant in the youngest group. This means that as the intensity of the informational style increases, religiosity increases only in the period of adolescence. As the normative style increases, religiosity increases in each age group, although most strongly in the early adulthood group. As the diffuse-avoidant style increases, religiosity decreases in adolescence, but there is no relation in the period of emerging and early adulthood.

4. Discussion

4.1. Intensification of Identity Styles during Adolescence, Emerging Adulthood, and Early Adulthood

One of the aims of this study was to examine how individual identity styles are formed during adolescence, emerging adulthood, and early adulthood. In each period analysed, the respondents reported all the three identity styles. A similar phenomenon was observed in other studies (Berzonsky 1990). Based on previous research, we expected that the level of normative identity style does not differentiate the distinguished age groups (Kroger and Marcia 2011). The results of our study confirm these expectations. Respondents from the developmental periods did not differ in their level of normative identity style. This style is associated with a passive approach to forming one’s own identity and perceiving one’s decisions and behaviours as externally determined (Schwartz et al. 2005; Soenens et al. 2005). The normative identity style has adaptive functions in societies and cultures where mutual consent is highly valued (Bosma and Kunnen 2001). The comparable level of normative identity style in different age groups in the study may be due to the still highly valued collectivist ideas in Polish society, which refer to agreement and cooperation. We also obtained confirmation of expectations regarding the characteristics of other styles of identity in the age groups. Adolescents, in comparison with older groups, presented the highest level of the diffuse-avoidant identity style, and at the same time the lowest level of the informational style based on self-reliant searching for information that is important to the self. A small increase in exploration (related to the level of the informational style) in adolescence is also reported in a previous study (i.e., Klimstra et al. 2010). In this study, we found a significant difference in the level of the informational style between adolescents compared to the groups of emerging and early adults. These results are consistent with the results of other studies (Bosma and Kunnen 2008; Luyckx et al. 2008) and allow us to conclude that an in-depth reflection on one’s own identity begins only in late adolescence. Young people are at the beginning of their journey of self-formation, and despite their efforts to independently search for their self-concept, they often avoid identity resolution by conforming to the demands of the situation or adopting other people’s expectations (Arnett 2000; Schwartz et al. 2013). The higher intensity of informational style in emerging adulthood and early adulthood groups as compared with adolescents indicates an intensification of the process of building a mature identity during these developmental phases (Kroger 2015; Kroger et al. 2010; Kłym and Cieciuch 2016; Topolewska-Siedzik and Cieciuch 2018; Markovitch et al. 2017). This is fostered by the development of cognitive competence (mastering formal and then post-formal operations) and achieving independence from authority figures. Formal-operational and post-formal thinking allow us to critically appraise both the knowledge we acquire and the views expressed by authorities, and to look for different sources of this knowledge. This knowledge is then assimilated into different systems of the self. Therefore, people who use this way of thinking do not automatically adopt behavioural patterns, views, and value systems from others.

New social experiences after leaving the family home are also significant; a clash with opinions different from one’s own, and noticing the possibility of shaping a lifestyle different from one’s own, may stimulate the development of a young person towards openness to new experiences and the independent construction of one’s own life path (Bosma and Kunnen 2001).

The emerging adulthood and early adulthood groups did not differ in the intensity of identity informational and diffuse-avoidant styles. The lack of significant differences with regard to informational style between the emerging adulthood and early adulthood groups may indicate that identity formation in adulthood is associated with increased commitment, but not with exploration (Côté and Schwartz 2002). Indeed, new family and professional roles in early adulthood require new commitments and responsibilities for oneself and others. The absence of differences may also indicate stabilisation in terms of the dominant identity style. If a person adopts a certain style during emerging adulthood, it remains dominant also in later periods of life.

4.2. Religiosity in Different Developmental Periods (Adolescence, Emerging Adulthood, and Early Adulthood)

In the current study, we hypothesized that the level of religiosity would be comparable between the first two groups, but higher in early adulthood (Stolzenberg et al. 1995; McNamara Barry et al. 2010; Sullivan 2012). Our expectations were only partially confirmed by the results. This is because the general index of the centrality of religiosity does not differentiate the developmental groups and indicates a level of heteronomous religiosity, according to Huber’s concept. The indicator of the centrality of religiosity is the sum of the intensity of the five dimensions of religiosity as indicated by Huber: (1) interest in religious issues (intellect), (2) religious experience, (3) prayer (private practice), (4) religious beliefs (ideology), and (5) worship (public practice).

The result obtained in our study show that the sphere of religion and religiosity is important in the lives and activities of the individuals in the survey; however, undertaking religious activity, both in the private sphere and in behaviours related to worship (public practice) is mainly motivated by social norms and expectations. It is worth noting that the average score of religiosity in each group is close to the transition from the heteronomous to the autonomous level, which may indicate the presence of elements of autonomous experience of religion and a less institutionalised approach to it in the religiosity of all the subjects (Arnett and Jensen 2002; Stoppa and Lefkowitz 2010). We expected a similar level of religiosity in the adolescent and emerging adulthood groups because most people in emerging adulthood report few changes in their experience of religiosity, and changes often occur in adolescence (Smith and Snell 2009). Studies of adolescents in Western societies suggest a clear decline in their religiosity. As they mature, fewer adolescents believe in God, and those who declare themselves as believers are less likely to admit to participating in religious practices (Desmond et al. 2010; Hayward and Krause 2013; Petts 2009; Pearce and Denton 2011). The results for Polish adolescents and emerging adults suggest that religion is important in everyday life and in the course of making important decisions. However, these results may be specific to Polish culture, where the majority of the population declares themselves to be Catholic. Further, on average, young people in Poland live with their parents much longer than their Western peers, and therefore, in matters of faith and religiosity, they are influenced by parental authority over a longer period of time. As research shows, the religiosity of even adult children is determined by the religious attitudes of their parents (Wuthnow 1999). In addition, a significant proportion of students from Catholic families become involved in academic pastoral centres even if they leave the family home, which prevents their religiosity from declining.

Based on the results of research on adults’ religiosity (Stolzenberg et al. 1995), it was expected that they would have higher levels of religiosity compared with adolescents and those in emerging adulthood. In our study, this variation in levels of religiosity did not occur. However, if we agree with the conviction that a “return to religious practice”, and consequently, religious involvement, is fostered by such events typical of early adulthood, such as marriage and childbirth and christening (Ingersoll-Dayton et al. 2002; Uecker et al. 2007), then these are associated with a normative approach to religiosity and perhaps a primary focus on rituals, which is an external dimension reinforcing heteronomous religiosity.

When characterising the groups in terms of their level of religiosity, it is worth bearing in mind that the average level of religiosity found in our study carries a large interindividual variation that has been present since adolescence, allowing the authors of longitudinal studies to distinguish several paths of religious development (Dew et al. 2020).

4.3. Identity Style as a Predictor of Religiosity in Different Developmental Periods

The main aim of the study was to examine the links between identity styles and the level of religiosity in different developmental periods (adolescence, emerging adulthood, and early adulthood). It was expected that, due to the significant changes which young people undergo, as well as the different contexts of their development in the aforementioned periods, developmental stages would be important for the extent to which each identity style is a predictor of religiosity.

We hypothesized that an increase in the intensity of the informational identity style would be conducive to adolescents achieving more profound religiosity, while this identity style would not have a significant impact on religiosity in the later periods.

The results obtained in this study confirmed this expectation: adolescents’ informational identity style can predict the formation of their religiosity. The more actively an adolescent develops their independent exploration of different areas of activity in order to gain information about themselves and the world, the more mature religiosity they display. As mentioned, the centrality of religiosity depends on the intensity of several dimensions that describe religiosity. The positive link between the informational style of identity and the increase in the level of religiosity among the adolescents may indicate that, in building their own worldview, people with high openness to new information show deep interest in religious issues. This is because it is an area of knowledge that can provide important answers to questions about the meaning of life that often arise in this period of life, which was pointed out by Moshman (2011) when he claimed that adolescents’ identity is constructed around moral and religious ideals. Another experience that may also be important for religious teenagers in the context of “adolescent idealism” is the experience of the presence of transcendence and communing with God during individual prayer, which, according to Huber, represents such dimensions of religiosity as Religious Experience and Prayer. Moreover, previous studies using other measures of religiosity found that the informational style of identity is a positive predictor of adolescents’ involvement in faith (Leak 2009; Puffer et al. 2008).

As expected for the older groups (i.e., emerging adulthood and early adulthood), the increase in the intensity of the informational style of identity was not significant in shaping their religiosity. This result may be explained by the high involvement of young people entering adulthood and taking on adult responsibilities in preparing for and then fulfilling the tasks of early adulthood (e.g., intimate relations, building a lasting relationship, and fulfilling professional responsibilities, which may weaken worldview interests and explorations (Havighurst 1956; Luyckx et al. 2008; Arnett 2006)). The fact that the informational style only plays an important role in shaping religiosity during adolescence may indicate that, later in life, after significant developmental transitions in both identity and religiosity, a young person’s worldview becomes stable. Then, when their religious commitment is consolidated, openness to new experiences, exploration, and critical thinking already play a much smaller role in determining the place of religious constructs in the personality structure.

The results of the study also allow us to conclude that just as the informational style is a positive predictor of religiosity in adolescents, it is also only in adolescents that the diffuse-avoidant style is negatively related to religiosity. The lack of significant links between this identity style and religiosity in the older groups may confirm that, in emerging and early adulthood, the domain of religious life is less important for the fulfilment of the developmental tasks falling within these developmental phases. Therefore, both intensive identity exploration and a lack thereof are not significantly associated with faith and religiosity. The decline in the importance of the diffuse-avoidant style may also be due to its low intensity during emerging and early adulthood.

The results of this research also indicate that the level of normative style can predict the overall level of religiosity in each age group analysed. Thus, building an individual identity based on ready-made patterns originating in social norms or coming from authorities promotes progressive changes in religiosity in all age groups. As previously described, religiosity in each group represents a type of heteronomous religiosity, (i.e., respondents representing different developmental periods from adolescence to early adulthood) most often make reference to external authorities when making decisions on matters of faith. Additionally, the search for religious knowledge as well as the strength of beliefs is firmly rooted in social norms and expectations. Faith and religiosity have mainly adaptive functions. In Polish culture, which is dominated by a traditional approach to Catholicism, the normative style of identity may facilitate the formation of religiosity determined by external forms and requirements, rather than foster independent, autonomous searches based on individual contact with God.

Therefore, a style of identity decisions based on the use of ready-made models from authorities is revealed in a similar approach to religiosity and is conducive to its development not only in the period of intensive worldview search (adolescence), but also later, especially when it is a heteronomous type of religiosity. Confirmation can be found in the results of previous studies, which show that the formation of one’s own faith and spirituality is based on the same processes as identity formation (Berzonsky 1992; Gebelt et al. 2009). The result shows a natural consistency between the normative identity style and religiosity with a strong touch of heteronomy. A person with the normative style accepts values, norms, and rules from significant others and conforms to social expectations. In Polish society, which is to a large extent a Catholic society (at least declaratively), religion is naturally written into the life of the individual, especially in the realm of rituals, traditions, and religious practices. Among our study participants, heteronomous religiosity that dominates, which means that even if a person attributes some importance to religion, religious constructs are not placed centrally in their personality structure but rather have a subordinate position. This may confirm that religion does not set life goals or define a person’s life path; nor is it the object of deeper personal reflection, and religiosity does not imply the pursuit of a personal relationship with God. For a heteronomous person, religion is mainly about specific norms, rules, and rituals, the observance of which serves the adaptation and satisfaction of the needs of the individual. People with the normative identity style do not develop a personal attitude towards important life issues, which is also manifested in their attitude towards religion, as the results of our study show.

5. Conclusions and Limitations

The current study examined the relation between identity styles and the centrality of religiosity in three developmental periods: adolescence and emerging and early adulthood. Results suggest that while the intensity of the informational style favours religiosity only in adolescence, and the intensity of the diffuse-avoidant style decreases the intensity of religiosity in adolescence, the intensity of the normative style favours religiosity in all three periods. Interestingly, correlations between each of the identity styles and religiosity were only noted in adolescence. The fact that each of the identity styles is related to religiosity in adolescence may indicate that, during the time of the construction of one’s identity and the significant changes in personal religiosity that occur during this period, these spheres are in the strongest relation, and each choice concerning identity style translates into an intensification or decline of religiosity. The relation between the normative style and religiosity in each developmental period can be explained by the nature of religiosity, which is heteronomous in the vast majority of people. The lack of openness to new experiences, rigid and dogmatic commitment, appealing to authorities, and resisting changes concerning the “self”, which is characteristic of the normative style, translates into a religiosity that is based more on tradition and the adoption of certain ready-made models or ways of thinking about religious issues than on personal reflection and the central positioning of religious constructs in the personality structure.

Although this was a large study with over one-thousand participants across three developmental periods, a limitation of the study is the homogeneity of the group in terms of the centrality of religiosity. The participants primarily reported a heteronomous religiosity, which may of course reflect the actual level of religiosity of adolescents and young adults in Polish society, but this also limits the possibility of drawing conclusions about the way personal identity is constructed for the development of religiosity in the relations examined. In subsequent studies, it would be worthwhile to ensure a greater diversity of the group in terms of religiosity and the location of religiosity in the personality structure. In order to investigate the relation between the formation of identity style and religiosity over the course of life, it would be worthwhile to conduct longitudinal studies that would make it possible to indicate the changes taking place both in the sphere of identity and religiosity over the course of life, as well as to determine the interrelations between them at different stages of development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G., D.C., E.T.-S. and J.C.; methodology: E.G., D.C., E.T.-S. and J.C.; investigation: E.G. and D.C.; writing—original draft preparation: E.G., D.C., E.T.-S. and J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This piece of research was not by nature a clinical experiment, and as such it did not need to be adjudicated by the Research Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Allport, Gordon Willard. 1988. The Individual and His Religion [Osobowość i religia]. Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy PAX. First published 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. 2000. Emerging Adulthood: A Theory of Development from the Late Teens through the Twenties. American Psychologist 55: 469–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. 2006. Emerging Adulthood: Understanding the New Way of Coming of Age. In Emerging Adults in America: Coming of Age in the 21st Century. Edited by Jeffrey Jensen Arnett and Jennifer Lynn Tanner. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. 2010. Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen, and Lene Arnett Jensen. 2002. A Congregation of One: Individualized Religious Beliefs among Emerging Adults. Journal of Adolescent Research 17: 451–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzonsky, Michael D. 1989. Identity Style: Conceptualization and Measurement. Journal of Adolescent Research 4: 268–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzonsky, Michael D. 1990. Self-construction over the life-span: A process perspective on identity formation. In Advances in Personal Construct Psychology: A Research Annual. Edited by Greg J. Neimeyer and Robert A. Neimeyer. Greenwich: Elsevier Science/JAI Press, vol. 1, pp. 155–86. [Google Scholar]

- Berzonsky, Michael D. 1992. Identity Style Inventory (ISI3). Revised Version. New York: Academic Press of the State University of New York at Cortland. [Google Scholar]

- Berzonsky, Michael D. 2003. Identity Style and Well-Being: Does Commitment Matter? Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research 3: 131–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzonsky, Michael D. 2004. Identity Style, Parental Authority, and Identity Commitment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 33: 213–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzonsky, Michael D., and Joseph R. Ferrari. 1996. Identity orientation and decisional strategies. Personality and Individual Differences 20: 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzonsky, Michael D., and Linda S. Kuk. 2000. Identity Status, Identity Processing Style, and the Transition to University. Journal of Adolescent Research 15: 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, Harke A., and E. Saskia Kunnen. 2001. Determinants and Mechanisms in Ego Identity Development: A Review and Synthesis. Developmental Review 21: 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, Harke A., and E. Saskia Kunnen. 2008. Identity-in-context is not yet identity development-in-context. Journal of Adolescence 31: 281–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Côté, James E., and Seth J. Schwartz. 2002. Comparing psychological and sociological approaches to identity: Identity status, identity capital, and the individualization process. Journal of Adolescence 25: 571–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, Phebe. 1998. Freshman to senior year: A follow-up study of identity, narcissism and defense mechanisms. Journal of Research in Personality 32: 156–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, Phebe. 2017. Identity change between late adolescence and adulthood. Personality and Individual Differences 104: 538–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżowska, Dorota, and Kamila Mikołajewska. 2014. Religiosity and young people’s construction of personal identity. Annals of Psychology 17: 131–54. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond, Scott A., Kristopher H. Morgan, and George Kikuchi. 2010. Religious Development: How (and Why) Does Religiosity Change from Adolescence to Young Adulthood? Sociological Perspectives 53: 247–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dew, Rachel E., Bernard Fuemmeler, and Harold G. Koenig. 2020. Trajectories of Religious Change from Adolescence to Adulthood, and Demographic, Environmental, and Psychiatric Correlates. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 208: 466–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duriez, Bart, and Bart Soenens. 2006. Personality, identity styles, and religiosity: An integrative study among late and middle adolescents. Journal of Adolescence 29: 119–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duriez, Bart, Bart Soenens, and Wim Beyers. 2004. Personality, Identity Styles, and Religiosity: An Integrative Study among Late Adolescents in Flanders (Belgium). Journal of Personality 72: 877–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duriez, Bart, Ilse Smits, and Luc Goossens. 2008. The relation between identity styles and religiosity in adolescence: Evidence from a longitudinal perspective. Personality and Individual Differences 44: 1022–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G., and Andrea K. Henderson. 2011. Religion and mental health: Through the lens of the stress process. In Toward a Sociological Theory of Religion and Health. Edited by Anthony Blasi. Leiden: Brill, pp. 11–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, Erik H. 1964. Insight and Responsibility. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, Erik H. 1968. Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Fadjukoff, Päivi, Katja Kokko, and Lea Pulkkinen. 2007. Implications of Timing of Entering Adulthood for Identity Achievement. Journal of Adolescent Research 22: 504–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, James D., and Beth Laforce. 1999. A Longitudinal Study of Moral, Religious, and Identity Development in a Christian Liberal Arts Environment. Journal of Psychology and Theology 27: 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, James. 1981. Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Human Development and the Quest for Meaning. San Francisco: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Gebelt, Janet L., Sara K. Thompson, and Kristine A. Miele. 2009. Identity Style and Spirituality in a Collegiate Context. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research 9: 219–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajales, Tevni E., and Brittany Sommers. 2016. Identity Styles and Religiosity: Examining the Role of Identity Commitment. Journal of Research on Christian Education 25: 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guerreiro, Maria das Dores, Abrantes Pedro, and Ines Pereira. 2004. Transitions in Youth Trajectories and Discontinuities Case Studies Summary Report. Manchester: Manchester Metropolitan University. [Google Scholar]

- Gurba, Ewa. 2013. Nieporozumienia z Dorastającymi Dziećmi w Rodzinie. Uwarunkowania i Wspomaganie [Misunderstandings with Adolescent Children in the Family. Underpinning and Support]. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Havighurst, Robert J. 1956. Research on the Developmental task Concept. The School Review 64: 215–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2018. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Andrew F., and Amanda K. Montoya. 2017. A Tutorial on Testing, Visualizing, and Probing an Interaction Involving a Multicategorical Variable in Linear Regression Analysis. Communication Methods and Measures 11: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, R. David, and Neal Krause. 2013. Patterns of change in religious service attendance across the life course: Evidence from a 34-year longitudinal study. Social Science Research 42: 1480–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, Stefan. 2003. Zentralität und Inhalt: Ein neues Multidimensionales Messmodel der Religiosität [Centrality and Content: A New Multidimensional Measurement Model of Religiosity]. Opladen: Leske and Budrich. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan. 2007. Are religious beliefs relevant in daily life? In Religion Inside and Outside Traditional Institutions. Edited by Heinz Streib. Leiden: Brill, pp. 211–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll-Dayton, Berit, Neal Krause, and David Morgan. 2002. Religious Trajectories and Transitions over the Life Course. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development 55: 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordyn, Marsha, and Mark Byrd. 2003. The relationship between the living arrangements of university students and their identity development. Adolescence 38: 267–78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- King, Pamela Ebstyne. 2003. Religion and Identity: The Role of Ideological, Social, and Spiritual Contexts. Applied Developmental Science 7: 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimstra, Theo A., William W. Hale, III, Quinten A. W. Raaijmakers, Susan J. T. Branje, and Wim H. J. Meeus. 2010. Identity formation in adolescence: Change or stability? Journal of Youth and Adolescence 39: 150–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłym, Maria, and Jan Cieciuch. 2016. Dynamika poszukiwania tożsamościowego w różnych domenach we wczesnej adolescencji: Wyniki badań podłużnych [The dynamics of identity exploration in various domains in early adolescence: The results of a longitudinal study]. Annals of Psychology 19: 221–37. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Laura B., Matt McGue, and William G. Iacono. 2008. Stability and change in religiousness during emerging adulthood. Developmental Psychology 44: 532–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroger, Jane. 2007. Why is identity achievement so elusive? Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research 7: 331–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroger, Jane. 2015. Identity development through adulthood: The move toward "wholeness". In The Oxford Library of Psychology. The Oxford Handbook of Identity Development. Edited by Kate C. McLean and Moin Syed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kroger, Jane, and James E. Marcia. 2011. The identity statuses: Origins, meanings, and interpretations. In Handbook of Identity Theory and Research: Structures and Processes. Edited by Seth J. Schwartz, Koen Luyckx and Vivian L. Vignoles. London: Springer, vol. 1, pp. 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroger, Jane, Monica Martinussen, and James E. Marcia. 2010. Identity status change during adolescence and young adulthood: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescence 33: 683–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leak, Gary K. 2009. An assessment of the relationship between identity development, faith development, and religious commitment. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research 9: 201–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, Eva S. 2005. Things Have Gotten Better: Developmental Changes among Emerging Adults after the Transition to University. Journal of Adolescent Research 20: 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtwarck-Aschoff, Anna, Paul van Geert, Harke Bosma, and Saskia Kunnen. 2008. Time and identity: A framework for research and theory formation. Developmental Review 28: 370–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, Koen, Seth J. Schwartz, Luc Goossens, and Sophie Pollock. 2008. Employment, Sense of Coherence, and Identity Formation: Contextual and Psychological Processes on the Pathway to Sense of Adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Research 23: 566–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcia, James E. 1966. Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 3: 551–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markovitch, Noam, Koen Luyckx, Theo Klimstra, Lior Abramson, and Ariel Knafo-Noam. 2017. Identity exploration and commitment in early adolescence: Genetic and environmental contributions. Developmental Psychology 53: 2092–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markstrom-Adams, Carol. 1999. Religious involvement and adolescent psychosocial development. Journal of Adolescence 22: 205–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markstrom-Adams, Carol, and Melanie Smith. 1996. Identity formation and religious orientation among high school students from the United States and Canada. Journal of Adolescence 19: 247–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara Barry, Carolyn, Larry Nelson, Sahar Davarya, and Shirene Urry. 2010. Religiosity and Spirituality during the Transition to Adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development 34: 311–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, William R., and Carl E. Thoresen. 2003. Spirituality, religion, and health: An emerging research field. American Psychologist 58: 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshman, D. 2011. Adolescent Rationality and Development: Cognition, Morality, and Identity, 3rd ed. Hove: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Mitchell S. 1985. Identity and the development of religious thinking. New Directions for Child Development 30: 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, Lisa, and Melinda Lundquist Denton. 2011. A Faith of Their Own: Stability and Change in the Religiosity of America’s Adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petts, Richard J. 2009. Family and Religious Characteristics’ Influence on Delinquency Trajectories from Adolescence to Young Adulthood. Sociological Review 74: 465–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puffer, Keith A., Kris G. Pence, T. Martin Graverson, Michael Wolfe, Ellen Pate, and Stacy Clegg. 2008. Religious Doubt and Identity Formation: Salient Predictors of Adolescent Religious Doubt. Journal of Psychology and Theology 36: 270–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnerus, Mark D. 2003. Linked Lives, Faith, and Behavior: Intergenerational Religious Influence on Adolescent Delinquency. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42: 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnerus, Mark D., and Jeremy E. Uecker. 2006. Finding faith losing faith: The prevalence and context of religious transformations during adolescence. Review of Religious Research 47: 217–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Seth J., James E. Côté, and Jeffrey Jensen Arnett. 2005. Identity and Agency in Emerging Adulthood: Two Developmental Routes in the Individualization Process. Youth & Society 37: 201–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Seth J., M. Brent Donnellan, Russell D. Ravert, Koen Luyckx, and Byron L. Zamboanga. 2013. Identity development, personality, and well-being in adolescence and emerging adulthood: Theory, research, and recent advances. In Handbook of Psychology: Volume 6. Developmental Psychology. Edited by Richard M. Lerner, M. Ann Easterbrooks, Jayanthi Mistry and Irving B. Weiner. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 339–64. [Google Scholar]

- Senejko, Alicja. 2010. Inwentarz Stylów Tożsamości (ISI) Michaela D. Berzonsky’ego—Dane psychometryczne polskiej adaptacji kwestionariusza [Michael D. Berzonsky’s Inventory of Identity Styles (ISI)—Psychometric data of the Polish adaptation of the questionnaire]. Psychologia Rozwojowa 15: 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Christian, and Patricia Snell. 2009. Souls in Transition: The Religious & Spiritual Lives of Emerging Adults. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Soenens, Bart, Michael D. Berzonsky, Maarten Vansteenkiste, Wim Beyers, and Luc Goossens. 2005. Identity Styles and Causality Orientations: In Search of the Motivational Underpinnings of the Identity Exploration Process. European Journal of Personality 19: 427–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, Heidi E., Joseph A. Olsen, Teri M. Henke, and Brian K. Barber. 2013. Adolescent Religiosity and Psychosocial Functioning: Investigating the Roles of Religious Tradition, National-Ethnic Group, and Gender. Child Development Research 2013: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolzenberg, Ross M., Mary Blair-Loy, and Linda J. Waite. 1995. Religious participation in early adulthood: Age and family life cycle effects on church membership. American Sociological Review 60: 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoppa, Tara M., and Eva S. Lefkowitz. 2010. Longitudinal changes in religiosity among emerging adult college students. Journal of Research on Adolescence 20: 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Susan Crawford. 2012. Living faith: Everyday Religion and Mothers in Poverty. Chicago: University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, Jennifer Lynn. 2006. Recentering During Emerging Adulthood: A Critical Turning Point in Life Span Human Development. In Emerging Adults in America: Coming of Age in the 21st Century. Edited by Jeffrey Jensen Arnett and Jennifer Lynn Tanner. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 21–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topolewska-Siedzik, Ewa, and Jan Cieciuch. 2018. Trajectories of identity formation modes and their personality context in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 47: 775–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uecker, Jeremy E., Mark D. Regnerus, and Margaret L. Vaaler. 2007. Losing My Religion: The Social Sources of Religious Decline in Early Adulthood. Social Forces 85: 1667–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, Alan S. 1982. Identity development from adolescence to adulthood: An extension of theory and a review of research. Developmental Psychology 18: 341–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, Alan S., and Jeffrey A. Goldman. 1976. A longitudinal study of ego identity development at a liberal arts college. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 5: 361–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, Alan S., Patricia S. Geary, and Caroline K. Waterman. 1974. Longitudinal study of changes in ego identity status from the freshman to the senior year at college. Developmental Psychology 10: 387–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, Paul J., Ronald J. Morris, Ralph W. Hood, J. Trevor Milliron, and Nancy L. Stutz. 1998. Religious orientation, identity and the quest for meaning in ethics within an ideological surround. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 8: 149–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuthnow, Robert. 1999. Growing Up Religious: Christians and Jews and Their Journeys of Faith. Boston: Beacon. [Google Scholar]

- Zarzycka, Beata. 2007. Skala Centralności Religijności Stefana Hubera [Stefan Huber’s Centrality of Religiosity Scale]. Annals of Psychology 10: 133–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zarzycka, Beata. 2011. Polska adaptacja Skali Centralności Religijności S. Hubera. In Psychologiczny Pomiar Religijności. Edited by Marek Jarosz. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).