1. Introduction

This article focuses on two particular (parts of) liturgical ceremonies from the twelfth century in order to shed light on the complexity of the broad phenomenon of medieval Latin liturgy. In scholarly work concerning Western Christianity, “the medieval liturgy” is a common term for an assumed totality of public devotional activities during the Middle Ages, as indicated, e.g., in the titles of several volumes on medieval liturgy (

Martimort et al. 1986;

Heffernan and Matter [2001] 2005;

Pfaff 2009).

1 There are problems with this terminology, however. Not only was the word liturgy not used during the Middle Ages (

Symes 2016, p. 240), but the idea of “the medieval liturgy” presupposes a stable, well-defined phenomenon with clear boundaries, something which is at odds with medieval sources (

Flanigan et al. 2005;

Petersen 2007a, pp. 332–36;

2007b, pp. 89–90, 103;

Symes 2016, pp. 239–41;

Norton 2017, pp. 157–66). Medieval authors tended to use the term

officium (office) in the plural in general discussions of church ceremonies (

Petersen 2007b, p. 103;

Norton 2017, pp. 157–66), possibly thereby indicating a built-in diversity of the involved phenomena.

It has long been acknowledged that there was no liturgical uniformity during the Middle Ages (

Vogel 1986, p. 4). Even so, there seems to be an increased current awareness (during the last decades) about the fluidity, flexibility, and locality in liturgical construction and transmission. At the same time, it is obvious that many local variations regard details and not overall structures, such as for instance the general course of a medieval mass (

Dyer 2018, pp. 94–95). Thus, there seems on the one hand to be an experience of a phenomenon that is broadly the same everywhere over at least a period of more than half a millennium (up to the Council of Trent), in many respects also seamlessly continued in the Roman Catholic Church all the way up to the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s, and on the other hand a realization that, in spite of much continuity and sameness, there is an all-pervading amount of variation, mainly from place to place, even within the same province, but in many regards also over time.

Long-established scholarly constructions of seemingly stable medieval liturgical orders have recently been queried. The early Roman order for a papal Easter Day mass, the so-called Ordo Romanus I (or simply Ordo I), was generally considered an authoritative witness to the papal mass in Rome around 700 despite being preserved only in Carolingian manuscripts copied at least a century later (

Andrieu 1948–1961, vol. II, pp. 52–64;

Vogel 1986, pp. 136–38, 146). However, Romano (

Romano 2007) has recently argued convincingly that Ordo I did not remain unchanged between its original inception around 700 and its Carolingian reception. The construction of a stable, influential pontifical liturgical order in tenth century Mainz (

Vogel and Elze 1963) has recently been challenged by Henry Parkes (

Parkes 2015, pp. 18–29, 185–223;

2016). Additionally, another widely accepted idea may be challenged: that of a general liturgical order for the northern province of Nidaros (in medieval Norway, also covering Iceland, the North-Atlantic islands, and Greenland) established in the early thirteenth century (

Gjerløw 1968). This problematic notion of an overall liturgical order for the Nidaros province was advanced through Gjerløw’s edition, although she herself pointed out the factors that speak against such a proposition (

Gjerløw 1968, pp. 33–38;

Petersen 2007c, pp. 292–96).

One factor that makes it difficult to obtain an overview of medieval liturgical practices has to do with how they were recorded in various types of books. In addition to the books (for various parts of the clergy) for mass and the divine office, individual baptism, weddings, and funerals were recorded in manuals for priests, but many other practices that may be called occasional do not have their own particular books, and how practices were recorded in books also changed over the centuries (see

Vogel 1986). Specialized books, such as processionals, give songs for (certain) processions, and

troparia, which give tropes for mass, often include other occasional songs. One might also mention monastic customaries that are not liturgical books as such, but mostly will contain sections of liturgical practices as well as other ritual practices (for instance in the chapter), which to modern readers do not necessarily count as liturgy. The point in this context is simply to point out that medieval liturgy encompasses different kinds of ceremonies, some of which are far away from what in a modern context would be thought of as liturgy, while others are central to liturgical practices even today, such as baptism, weddings, and funerals. The so-called

mandatum ceremonies (ceremonies for washing the feet, emulating John 13:1–15) in a monastic context (it was also often carried out in cathedral practices), which often—but not necessarily only—took place on Maundy Thursday, are sometimes discussed in monastic customaries, but sometimes in other books (

Petersen 2015). Additionally, some of the special Good Friday ceremonies (including, e.g., the Adoration of the Cross) belong neither to the mass nor to the divine office. For many ceremonies, which one might call occasional, it is not easy to know in what kind of book they should be found. A reasonable proposition is to understand everything that is found in medieval liturgical books, or sections concerned with liturgy in other books, as liturgy. However, this may lead one to have to accept as liturgy a wine-drinking ceremony (on Easter Sunday) after the Easter Vespers procession to the baptismal font in the cathedral. Such a ceremony is described in manuscripts regarded as belonging to the Roman-German pontifical (

Vogel and Elze 1963, vol. 2, p. 117;

Petersen 2007a, p. 336; compare also

Flanigan et al. 2005).

Research in tropes and the uses of poetry in the medieval Latin mass have shown how schematic structures, basic to all students of medieval liturgy, as for instance the structure of the Ordinary of the Mass, would sometimes be complicated by more or less local traditions of inserted tropes (

Iversen 2010;

Haug 2018). In yet another field, that of liturgy and drama, there can be found no sharp delimitation between sung enactments of biblical (or saintly) narratives during mass, the daily office, or processions, and other parts of the offices of which they formed part (see further below). However, they have often been treated in scholarship as foreign to “the liturgy” (e.g., Young and see further below). The notion “paraliturgical” has often been used to characterize certain ceremonies or parts of ceremonies found in liturgical manuscripts viewed as not really part of “the liturgy,” often including so-called dramatic ceremonies. However, this notion rather reflects liturgical sensibilities of later (post-Tridentine) scholars sustaining an anachronistic idea of an “official liturgy” of the medieval church (

Flanigan 2014, p. 40;

Flanigan et al. 2005, p. 638;

Petersen 2007a, pp. 335–48;

Norton 2017, pp. 1–11, 170–73).

While scholarship since the mid-twentieth century has turned against the idea of a foreign dramatic impulse in medieval liturgy (

Hardison 1965;

Flanigan 2014;

Norton 2017), it is important to understand how new ideas were able to influence liturgical practices broadly. A keyword in studying medieval liturgical procedures, textually, musically, as well as ceremonially, is “transmission”. Texts, melodies, and ceremonial features travelled. Bishops, priests, monks, and others travelled, bringing with them manuscripts and local knowledge to new places or back home. New texts, melodies, or ceremonial features might then be used under different circumstances through appropriation. This would entail attempts to re-contextualize, to ensure that the new element would function and make sense in new surroundings, whether architecturally or in terms of fitting in to current practices and, not least, to the local understanding of what was important for a particular occasion. A new idea, that of enacting, at some point on Easter morning, the biblical story about Christ’s grave, where three women received the angelic message of his resurrection, could thus be transmitted all over central Europe during the tenth and eleventh centuries, while being diversified in numerous ways. The (unknown) beginning of this phenomenon, usually termed the

visitatio sepulchri (the visit to the sepulcher), thus led to an unwieldy tradition (preserved in close to 900 more or less similar, more or less different ceremonies, see both

Lipphardt 1975–1990 and

Evers and Janota 2013). This constituted the early part of an even broader phenomenon that many scholars, beginning in the nineteenth century, saw as the rise of a liturgical theater within medieval Latin liturgical practices. Gradually, it also came to include enactments of many other biblical narratives than those pertaining to the resurrection.

A notion for such ceremonies, “liturgical drama,” was coined and became a general scholarly, albeit much-discussed, standard term for all such sacred enactments in the medieval Latin church (

Rankin 1990;

Norton 2017; also

Young 1933;

Hardison 1965;

Lipphardt 1975–1990;

Flanigan 2014 (written ca. 1989);

Dronke 1994;

Petersen 2007a). As already mentioned, discussions often revolved around the idea that the sacred enactments were the results of an extra-liturgical dramatic impulse, somehow entering into “the liturgy,” until O.B. Hardison’s new, literary departure in 1965 led to new perspectives in scholarship focusing on understanding the liturgical function of these particular ceremonies embedded in liturgical practices. Other disciplines such as anthropology (ritual studies) were included into the discussions, as well as an altogether stronger interdisciplinary focus (

Flanigan 2014;

Rankin 1990;

Kobialka 1999;

Petersen 2007a;

Norton 2017). Altogether, interdisciplinarity and intermediality have increasingly become more important for liturgical studies, as for instance seen in collaborations between musicologists and textual scholars of different kinds in the study of tropes and sequences as well as gradually for the so-called dramatic liturgical ceremonies. The involvement of all five senses in liturgical practices has recently been discussed by Éric Palazzo (

Palazzo 2014), and an edited interdisciplinary volume dedicated to the five senses in the Middle Ages (

Palazzo 2016) also contributes greatly to the study of medieval liturgy. The latter volume contains articles pertinent to medieval liturgy by scholars from a number of different disciplines, including musicology, archeology of architecture, as well as articles dealing with sound, seeing, touch, smell, and taste.

In the twelfth century, new kinds of appropriations of the

visitatio sepulchri and other liturgical enactments appeared.

2 Some of these innovations may be connected to changes in contemporary sacramental thought, as suggested by Kobialka’s idea of a connection between Eucharistic discussions (c. 830 to 1215) and the rise of the mentioned

visitatio sepulchri tradition during that period (

Kobialka 1999;

Petersen 2009,

2017,

2019a).

3 Some

visitatio sepulchri ceremonies were constructed ceremonially to point to the resurrection as the background for the efficacy of the Eucharist (

Petersen 2007a, pp. 336–48;

2017, pp. 16–19). Further, during the early to mid-twelfth century, the understanding of the concept of a sacrament was influentially revised, not least by Hugh of St. Victor (

Fassler 2011, pp. 228–33;

Reibe 2020;

Feiss 2020). In the end, this resulted in a rather substantial narrowing of what would count as a sacrament through the seven (now well-known) sacraments of the Roman Church famously defined in Peter Lombard’s Sentences (Distinction II. 1, see Padri collegii S.

Bonaventurae 1916, pp. 52–53;

Lombard 2010, p. 9; cf.

Reibe 2020, p. 56). Up to and including Hugh of St. Victor’s

De sacramentis (written in the 1130s), liturgical ceremonies would fit the understanding of a sacrament. They were explicitly treated as such by Hugh under his notion of sacraments for the exercise of man (“propter exercitationem,”

De sacramentis I.9.3, see

Berndt 2008, p. 211;

Hugh of St Victor 2020, pp. 79–80) in an almost lyrical general description of the varieties and virtues of liturgical devotions and singing (

Berndt 2008, p. 214;

Hugh of St Victor 2020, pp. 82–83). However, in the systematic approach of Peter Lombard’s Sentences, there was no longer a place for seeing such liturgical human exercise as sacramental.

At the end of the thirteenth century, Bishop William Durand, in his

Rationale divinorum officiorum, unsurprisingly, referenced the seven sacraments (he had been present at the Council of Lyons in 1274 where Peter Lombard’s list of the seven sacraments was confirmed;

Van Roo 1992, p. 61, see also

Petersen 2021, p. 88). In Book 4 (chp. 42, Section 26), however, he also mentioned the older, broader way of understanding sacraments, using the traditional Augustinian definition of a sacrament (the one which Hugh of St. Victor revised): “in the broad sense, everything that is a sign of something sacred, whether it is sacred or not, is called a ‘sacramental sign’” (

Durand 2013, p. 376).

4 Remembering this old, broad sacramental understanding puts an interesting perspective on Durand’s valuation of images and material objects used in liturgical ceremonies, as for instance the Gospel books used for readings (

Petersen 2021, pp. 83–89).

The historical transformation of the notion of a sacrament can be seen as (part of) a background for how certain liturgical ceremonies, which were not as universal as, for instance, the Eucharist or the overall liturgical course of the mass, came to have a position outside of the main theological (and ecclesiastical) focus. Hence, it became possible for them to develop in a more free way, sometimes including also more entertaining or pedagogical features, as found in some (but far from all) enactments (

Petersen 2017, pp. 19–22; for such new elements appearing in the twelfth century, see also

Fassler 1992;

Petersen 2019b). Similarly, substantial variations could also happen closer to a traditional liturgical context, for instance based on poetical extension, as long as these developments did not confront essential norms of the Church. The delimitation of the sacraments was one major way of defining what was particularly essential; in addition, a general sensibility of decorum also set limits for activities in churches (cf. condemnations of certain particularly problematic “theatrical” practices—including soldiers and weapons—in the twelfth century, see

Young 1933, vol. II, pp. 411–16;

Petersen 2011, pp. 238–42).

In the twelfth century, ambiguities between traditional notions of sacramentality and the new, gradually evolving understanding may similarly have caused a loss of transparency concerning how to valuate practices either as sacrosanct and untouchable or open to creative transformation, maybe even to discontinuation. What I mean by creative liturgical or devotional freedom at this point in history should be seen by comparison with the Carolingian era. Creativity within the old, broad sacramental understanding had been extremely important for the development of liturgical song (words and vocal sound) during the Carolingian era (

Petersen 2004,

2020a,

2020b;

Page 2010;

Iversen 2010;

Haug 2015). Voices were occasionally raised against the new inventions, for instance at the Council of Meaux in 845 (

Iversen 2010, pp. 14–15). However, the creative efforts of the ninth to tenth centuries were altogether part of an overall attempt to establish an authoritative and efficacious worship for the Carolingian realm (

McKitterick 2008, esp. chp. 5,

Correctio, knowledge and power, pp. 292–380; see also

Petersen 2020b, pp. 67–70).

By contrast, the theological reforms of the Victorines (and Augustinian canons regular altogether) as well as Peter Lombard a couple of hundred years later must be seen in the context of the ecclesiastical Gregorian movement, thus as part of a strengthening of the institutional papacy (

Coolman 2010, pp. 103–4;

Fassler 2011, p. 214;

Reibe 2020, pp. 23, 51). Liturgical or devotional freedom at this time, correspondingly, was a matter of freedom from an overall institutional centralized control, not a question of piety or faith. In the second half of the century, liturgical matters in general were no longer seen as part of the central means for salvation, and therefore not a focal point for most theologians. At least since the papacy of Gregory VII (1073–1085), there had been a strong focus on the church as the head of medieval society altogether, politically and religiously. Such a focus also led to theological decisions, not least the formal confirmation of the theory of transubstantiation as a solution to the long-standing theological and philosophical debates on the Eucharist, at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. This decision also involved a strong focus on priests, who alone were able to effectuate this transubstantiation according to the first constitution of the council (

Tanner 1990, vol. I, pp. 230–31). The new definitions of sacraments, of the very holy, untouchable, the means of salvation of the Church, as well as the focus on priestly spiritual power, made room for pious, devotional creativity outside of this most holy area, as long as it was not felt to challenge the central church institution.

5 This also elucidates a brief remark in the above mentioned Durand’s

Rationale divinorum officiorum, which makes clear that Durand knew of

visitatio sepulchri practices and had a rather relaxed attitude to how they might be carried out (

Petersen 2019a, pp. 126–27). Local institutional (in the end episcopal) control was clearly intact, but what fundamentally determined the limits of freedom were the central theologically defended powers of the overall ecclesiastical institution.

In the following section, two twelfth-century appropriations of the evolving traditions for the Easter morning ceremonial will be presented and discussed. Both have been treated earlier by scholars of “liturgical drama,” but in my view neither of them should be considered as dramas. I propose that a new discussion of these examples may contribute to an understanding of the balance between what appears as sacrosanct and unalterable on the one hand, and what appears as open to changes on the other.

2. Two Twelfth-Century Easter Ceremonies

- (a)

A Visitatio Sepulchri at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem

Before presenting the first of the Easter ceremonies, which constitutes the focus of this section, it is important to point to a particular liturgical use of time and place in medieval practices. A great part of the Christian church year is structured by the memory of specific events connected to Christ (Advent to Pentecost). From early times, this regarded the celebrations of Easter and Holy Week, but gradually, over the first Christian centuries, also other feasts evolved, not least, of course, those of the Christmas season. The schedule was complicated by Marian and other saints’ feasts, as well as by the weekly and daily cycles of masses and the divine office (see

Martimort et al. 1986, pp. 31–150, Jounel’s account of the liturgical year).

O.B. Hardison (

Hardison 1965, p. 86) saw two principles at work in the medieval church year, one a principle of articulation, marking the phases of the church year, for instance the beginnings of Lent and Easter with their very different moods. The other, which is the more important in the context here, Hardison called the principle of coincidence. These two principles are intimately connected. The principle of coincidence regards the tendency to not only mark but to represent particularly important events from Christ’s life liturgically. Such “coincidental” ceremonies have been known since Egeria’s account of her pilgrimage in (probably) the late fourth century, which to some extent tells of representational celebrations in Jerusalem at corresponding times and places of events such as Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday and the crucifixion on Good Friday (

McGowan and Bradshaw 2018).

Visitatio sepulchri ceremonies altogether, and thus also the

visitatio ceremony to be discussed in the following, were precisely such coincidental ceremonies. They all articulated as well as represented what happened on the first Easter morning when the biblical women came to the grave, at the exact (as much as possible) same time, choosing in general a place to represent Christ’s tomb (

Young 1933, vol. I, pp. 507–13, see also

Sheingorn 1987, pp. 6–25;

Petersen 2014).

In Jerusalem, as will be discussed below, the

visitatio ceremony took place near the actual grave of Jesus. In general, of course, the actual tomb was not at hand. Inspiration from ritual studies (especially the work of Clifford Geertz and Victor Turner) led Flanigan to a new interpretation of the liturgical meaning of a tenth-century trope for the introit on Easter Day in St. Martial de Limoges (in southern France). Textually and musically, the central sentences of this

quem queritis trope were identical with the Easter dialogue between the women and the angel at Christ’s grave constituting the central part of most

visitatio sepulchri ceremonies. Flanigan saw the meaning of the trope during the entrance procession to Easter Day mass as ritually actualizing the experience of Christ’s resurrection for the congregation (

Flanigan 1974). Its members were, so to say, spiritually transferred to the place and time of the original event, so that they would become witnesses of the resurrection. Similar interpretations of

visitationes sepulchri have followed, based on locally varied ceremonies (e.g.,

Iversen 1987, p. 163;

Flanigan 1996, pp. 10–29;

Petersen 2007a, pp. 339–40;

2017, pp. 14–15, 20). What Flanigan initiated was an understanding of a ritual technology, which may also be called a sacramental technology (

Petersen 2017, pp. 14–15) in contemporary understanding, since the ritual act functions as a sacred efficacious sign providing a congregation access to the holy moment of the first announcement of the resurrection. This seems to be basic to all

visitatio ceremonies (

Flanigan 1996;

Petersen 2017), including the one to be discussed in the following.

Records of a

visitatio sepulchri ceremony from the Latin Church of the Holy Sepulcher after the first crusade are preserved in a few manuscripts from the twelfth century. The earliest of these texts was copied for the Templars of the Holy Sepulcher between 1175 and 1187 (

Salvadó 2017, pp. 404–5;

Lipphardt 1975–1990 more broadly dates the manuscript to the mid-twelfth century, vol. VI, p. 406). According to Salvadó, this manuscript and another later manuscript giving the exact same version of the

visitatio, in both cases placed at the end of Matins on Easter Day, reflect the substantial liturgical reforms of Patriarch of Jerusalem, Fulcher of Angoulême (patriarch from 1146 to 1157). Fulcher’s liturgical reforms were carried out in connection with the rededication of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in 1149. Explicitly tied to Patriarch Fulcher’s name in the manuscripts, the reforms may well have been in place before or shortly after Fulcher’s death (

Salvadó 2017, pp. 403–6).

6 Martin Biddle, however, has pointed out that the mentioned dedication could not have been a dedication of the entire Crusader Church of the Holy Sepulcher, i.e., including the grand new Eastern part, since it was only finished in the 1160s (

Biddle 1999, p. 98).

7Salvadó emphasizes how Fulcher’s reform liturgy stressed the resurrection throughout the church year, pointing, e.g., to the persistent use, also outside Easter, of the Easter sequence

Victimae paschali laudes (

Salvadó 2017, pp. 416–18). This sequence explicitly reflects Mary Magdalene’s experience of Christ’s resurrection (John 20). In many

visitatio ceremonies on the European continent it was also quoted as part of the dialogue. Summarizing, Salvadó writes:

In reshaping the liturgy, Fulcher and his colleagues constructed a new devotional scheme, which placed the Resurrection at the very heart of the liturgy, not just during Eastertide, but throughout the liturgical year. […] The new liturgy turned almost every Sunday of the year into a celebration of the Resurrection […].

Here follows the visitatio sepulchri text from the mentioned Templars’ manuscript (an ordinal) from the twelfth century, as excerpted by Walther Lipphardt:

While this is sung, three young clerics should be prepared in the manner of women behind the altar, according to the old use, which we do not do presently [or: in this way] because of the great number of standing pilgrims. In the meantime, certainly, having finished the responsory, preceded by lamps and censers, they each carry a golden or silver vessel containing some ointment; three times they shall sing the antiphon: O Deus! Quis revoluet [… ] (Oh God! Who will roll the stone for us from the entrance to the tomb? […]). And when they have approached the entrance to the glorious sepulcher, two other clerics in front of or near the entrance to the mentioned sepulcher, holding candles in their hands and with their heads covered, shall sing in response: Quem queritis […] (Whom do you seek in the grave, followers of Christ?). The women shall reply: Jhesum Nazarenum […] (Jesus of Nazareth, heavenly beings). Then the two shall answer: Non est hic, surrexit […] (He is not here, he has risen as he foretold). While they sing, the women enter the sepulcher, and thereupon they shall return after having made a brief prayer; and standing in the middle of the choir they shall announce, singing with a high [or noble] voice: Alleluia, Resurrexit Dominus […] (Hallelujah, the Lord has risen! […]) When this is finished, the patriarch begins: Te deum laudamus […] (We praise you, Lord […]). Verse: In resurrectione tua Christe […] (In your resurrection, Christ, […])

The ceremony was mentioned by Salvadó and has been studied especially by (

Shagrir 2010) (also referenced in

Shagrir 2017). It has been known for a long time and was importantly edited and discussed by Karl Young, the most authoritative editor of what he thought of as drama in medieval liturgy, in the early twentieth century, referencing all three known

visitationes from Jerusalem (

Young 1933, vol. I, pp. 261–63 and 591, a note for p. 262). In his discussion, Young draws attention in particular to the clause “which we do not do presently because of the great number of standing pilgrims.” For Young (and others), this indicated that the performance of the

visitatio was discontinued at some point between its introduction in Jerusalem (from the West, presumably shortly after the conquest of Jerusalem in 1099) and the production of the Templars’ ordinal. Iris Shagrir, however, argues against Young and others that the ceremony was indeed performed in Jerusalem and not “copied for descriptive purposes only” (

Shagrir 2010, p. 71). Young, however, did not claim that it was not performed in Jerusalem, but only that its performance had been discontinued.

As translated above, the clause in the first sentence of the

visitatio text tells us that “we do not do” something pertaining to the old liturgical use, due to the congestion of pilgrims at the Holy Sepulcher. What exactly was discontinued is not clear from the Latin text. The clause might be read to only regard the mentioned preparations behind the altar. This, on the other hand, would not seem to solve the problem with the congestion of pilgrims very much. Shagrir points to another possible (but, also in her opinion, less likely) translation of the discontinuation clause connecting “non” and “modo”: “we follow venerable tradition but not only because there are many pilgrims present” (

Shagrir 2010, p. 71, n. 48). As she remarks, this would mean the opposite of the aforementioned understanding, indeed that the practice was continued. If, indeed, that might be the intended meaning, it seems to be an apologetic remark, defending the ceremony liturgically, which would be odd, considering that it was a venerable, traditional ceremony. The lack of musical notation for the

visitatio, in a manuscript that otherwise contains musical notation, might also indicate that the ceremony had been discontinued at the time of the copying (see n. 8).

As mentioned before, there is another somewhat later manuscript, the so-called Barletta manuscript, which contains the same

visitatio ceremony (this is the manuscript discussed by Shagrir). It includes the mentioned discontinuation remark and was possibly copied from a source common to both preserved manuscripts mentioned so far. It gives almost the exact same wording (there are only extremely minor and, as it seems, insignificant deviations between the two manuscript versions) and the same placement of the ceremony. The only possibly interesting difference between them is that while the Templar ordinal gives a verse to be sung after the Te deum, there is no similar mention in the Barletta-manuscript (

Lipphardt 1975–1990, vol. II (no. 408), p. 560, see also vols. VI: 221 and VII: 324–25).

A fourteenth-century manuscript, made for a Templar community in Breslau as a copy of the Templars’ liturgy in Jerusalem, also transmits what amounts to the same ceremony. This version has a somewhat changed wording, but the exact same liturgical procedures and songs, and the same liturgical placement (

Lipphardt 1975–1990, vol. II (no. 409), p. 561, see also vol. VI, p. 237; Young 1933, vol. I, p. 591). One marked change is that the clause about the discontinuation of the ceremony was moved to just before the Te deum, the traditional end of Matins on Easter Day. As in the Templar ordinal, the Te deum is also here followed by the verse

In resurrectione tua, Christe. The wording of the discontinuation clause is also slightly different: “Sed visitacionem hanc modo non facimus propter astancium multitudinem” (But we do not do this

visitatio presently (or: in this way) because of the great number [of people] standing). In this position and wording, the sentence makes it completely clear that the

visitatio, at least as presented in the text, was no longer performed at the time of the originally copied text. Although we are here dealing with a much later manuscript, this strengthens the conclusion that the

visitatio practice was indeed discontinued at some point around the mid-twelfth century. However, at the same time, this also confirms that the

visitatio indeed had been performed earlier, that is during the early decades of the twelfth century.

One interesting corollary of this has to do with where the

visitatio was performed, something that must have been central to its meaning for the participants, as will be discussed further below. Shagrir read the reference in the ceremony to the choir,

in medio choro, as a reference to the new crusader choir (

Shagrir 2010, pp. 69–70). However, based on Biddle’s aforementioned dating of the Eastern part of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, which has also been confirmed by recent archaeological work, this choir did not yet exist, or was at least unfinished at the time. Thus, the

visitatio must have been performed closer to the actual sepulcher of Christ than has hitherto been assumed. Mass would, of course, have been held in the building also before the Eastern part of the church was added, but then in the building around the Edicule, the construction around what was believed to be the grave of Christ. This building was established before 1106 at the latest and probably closer to the mid-eleventh century (

Biddle 1999, pp. 84–98) and was thus in place at the time we can assume the

visitatio to have been performed. The ceremony and its processions would thus have started at the altar in the Western chapel (later called the Coptic chapel), which is mentioned already in 1102/3. The performance would altogether have been enacted very close to, indeed at the very place of, Christ’s burial and resurrection, the Edicule (see

Biddle 1999, p. 84, as well as his Figure 63, p. 67; also

Georgopoulos et al. 2017, Figure 14, p. 493).

As all visitatio sepulchri ceremonies (see above), the Jerusalem visitatio can also be understood as a sacred, efficacious sign, spiritually transporting the congregation to the holy moment of the first announcement of the resurrection, as told in the biblical resurrection narratives. Only in Jerusalem, at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the congregation was already at the right place at the right time (by calendrical identification over the centuries). One could therefore have imagined that such a representational visitatio ceremony would have been experienced as less necessary. However, as it was introduced after the conquest of Jerusalem, this seems not to have been so. The ceremony reflects how the announcement of the resurrection outside the Edicule, right outside the grave of Christ, constitutes its ritual high point, first given by the two clerics representing the angels, whereafter follows the announcement of the women (after having examined the grave), sung with a noble or lofty voice. This made the participants in the ceremony (including the congregation present) witness the very moment they otherwise had only been told about and had celebrated in the offices of Easter Day. Here they witnessed the very moment where the biblical women heard the unbelievable message of the angels, went in to check the grave, and then came out announcing the resurrection to the faithful. Time between the first Easter morning and Easter Day mornings at the Holy Sepulcher in the early twelfth century thus collapsed into one sacred, transcendent moment. However, this must have changed in the middle of the century.

The earlier mentioned gradually emerging new sacramental understandings in the twelfth century may have contributed to make it more acceptable to discontinue the venerable ceremony at a point where practical difficulties made that advisable. Karl Young’s remark, that the mentioned discontinuation clause “enables us to visualize the jostling crowds of worshippers […] in their desire to see a dramatization of a Christian mystery” (

Young 1933, vol. I, p. 263), hardly captures the intentions of pilgrims and other faithful at the Holy Sepulcher on one of the holiest days in the church year. However, it may remind us that what these faithful were not allowed to see anymore at that time (mid-twelfth century) may no longer have been considered to be as sacrosanct and untouchable a ritual. To be sure, there is no evidence to connect the particular decision directly to changes in sacramental understanding in twelfth-century Paris. However, the mentioned new understandings, which in the end made sacraments a much smaller, clearly defined class of “things,” were based on changing ideas and sensibilities since the beginning of the century, not least in circles of Augustinian canons, and especially the Abbey of St. Victor (

Reibe 2020, p. 55). These circles formed an important background also for the liturgical reforms of Patriarch Fulcher (

Salvadó 2017, p. 407). Discontinuing a venerable, efficacious liturgical ceremony only for practical reasons does not seem likely; surely one could have found a solution to perform the

visitatio in a new way, something that would most likely have led to a copying of the new version in reform manuscripts, something that did not happen, at least based on the preserved sources.

- (b)

A Catalonian Easter Ceremony

The painstaking work with individual manuscripts and their often very individual problems constitutes partly a precondition and partly a way of controlling our attempts at establishing general knowledge about medieval church celebrations. On the one hand, it is virtually impossible to understand a medieval liturgical manuscript without some overall pre-knowledge of medieval liturgical procedures. On the other hand, in some cases, as already noted, liturgical scholars’ pre-knowledge of medieval liturgy has been based on anachronistic assumptions, e.g., drawn from post-Tridentine liturgical traditions. To be sure, to a large extent, post-Tridentine liturgical practices are continuations of, but not necessarily identical with, medieval practices. Additionally, scholars from other disciplines, dealing with medieval liturgical practices, may bring problematic assumptions to bear on such manuscripts. Theater historians in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century saw the

visitatio sepulchri ceremonies as antecedents to the early modern theater. As mentioned earlier, this led to the (problematic) notion of liturgical drama and, as we shall see in the following, in some cases has led scholars to bring specific theatrical assumptions to bear on liturgical ceremonies (for a specific example, see also

Petersen 2009, pp. 164–72).

Indeed, it seems impossible to approach any source material without assumptions from one’s own background; however, looking out for possible resistance against such assumptions may helpfully result in revisions of those assumptions through the evidence found in the manuscript. In addition, one must accept that a manuscript only provides us with a glimpse of what may have happened at one particular place at a certain time and also that it may contain errors. We cannot be sure that a ceremony found in only one particular manuscript was ever carried out, only that it had been contemplated for liturgical practice.

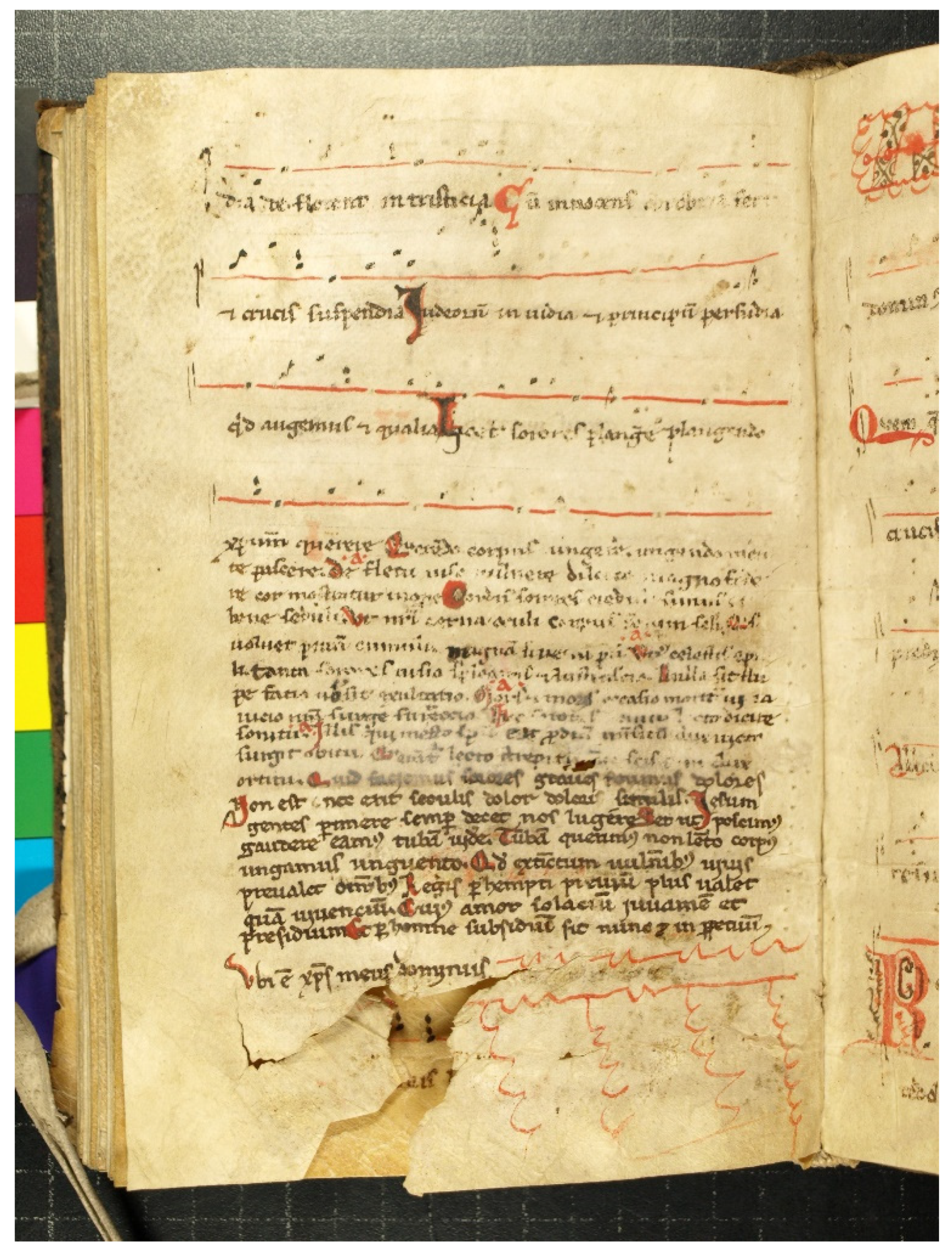

This section will deal with a few pages, fols. 58v to 62r from the twelfth-century Catalonian troper from the Cathedral of Vic, Arx. Cap., ms. 105 (CXI), briefly designated as TVic1 in the recent (monochrome) facsimile edition (

Gros i Pujol 2010; its text edited and discussed also in

Gros i Pujol 1999). The troper (a manuscript primarily containing tropes for mass items, in this case also numerous other poetic texts for liturgical use, but often without clear indication of the liturgical position) was originally copied in the early twelfth century but also contains sections copied later, over approximately the next hundred years. The pages I will be looking at have been dated to the middle or the last part of the 12th century (

Gros i Pujol 1999, pp. 44–45, 51–53;

Castro Caridad 2019, p. 144).

9These pages contain a purported “liturgical drama,” under the Catalan headline of

verses pascales de iii M<aries> (Easter verses of the three Maries; TVic1: fol. 58v;

Dronke 1994, pp. 92–93), probably added by a fifteenth-century hand (

Castro Caridad 2019, p. 144), a poetic and complex version of a

quem queritis or

visitatio sepulchri (see

Figure 1). A rubric on f. 60r (after the indicated Te deum, often marking the end of

visitatio sepulchri ceremonies at Matins) gives a new headline,

Versus de pelegri<no> (the margin has been cut off; Verses about the Stranger,

Dronke 1994, pp. 100–1; see

Figure 2). Some authors have understood the combined lines under both headlines as a

ludus paschalis, a term indicating the inclusion not only of the women at Christ’s grave, but also other biblical Easter narratives. Words of this ceremony (or these ceremonies) have been transcribed and discussed by several scholars. This includes Karl Young (

Young 1933, vol. I, pp. 678–82), Richard B. Donovan (

Donovan 1958, pp. 74–82), and Miquel Gros (

Gros i Pujol 1999, pp. 142–50, 216–20). Peter Dronke has given an edition of the Latin text with an English translation (

Dronke 1994, pp. 83–105). The manuscript is musically notated, but with a large omission (to be discussed below). The notation for the “liturgical drama” has been transcribed, expanded, and discussed by Higini Anglès (

Anglès 1988, pp. 273–81). A textual edition has also been given by Walther Lipphardt, indicating where musical notation is found, but without musical transcription (

Lipphardt 1975–1990, vol. V, pp. 1663–68).

10There are numerous problems in understanding these pages of the manuscript, which also do not indicate any specific liturgical placement for either part of the mentioned textual units. The way it was edited by Karl Young and Peter Dronke seems to indicate that there is altogether one connected drama. As mentioned, the rubric with the second headline is placed after the

quem queritis lines, but before a scene telling the story of Mary Magdalen and the resurrected Jesus as

hortulanus (gardener; John 20: 11–18). Gros (as well as Young) believes the rubric to be misplaced. He suggests that it properly belongs before the traditional opening song for

Peregrinus ceremonies,

Qui sunt hii sermones on fol. 61v (What are these things you are discussing;

Gros i Pujol 1999, pp. 149–50, 218, 220; cf.

Dronke 1994, pp. 102–3; for Peregrinus ceremonies, based on the Emmaus narrative, Luke 24: 13–35, see also

Young 1933, vol. I, pp. 451–83). Donovan and Castro Caridad understand the text as two dramas, an Easter morning drama and a special, innovative

Peregrinus drama for Easter Monday, the Easter morning drama ending with the Te deum before the second mentioned rubric (

Donovan 1958, pp. 85–86;

Castro Caridad 2019, p. 147, n. 15). As the Te deum was the traditional end of Sunday Matins (

Harper 1991: 93–95) and generally ended

visitatio sepulchri ceremonies placed at the end of Matins (as also the Jerusalem

visitatio discussed above), this in itself is a strong argument for such an understanding.

Peter Dronke gives a more ambiguous reading of this situation. As already mentioned, before the second rubric, the

versus de pelegri<no>, the

visitatio text concludes with the Te deum after a very traditional

quem queritis dialogue.

11 The

quem queritis dialogue, however, was preceded by what appears to be a highly original poetic lament by the three women and some anticipatory poetic lines concerning the buying of ointments, including a dialogue with a merchant. The text is unique to Vic (see also

Castro Caridad 2019, pp. 144–45). This part of the ceremony will be considered further below. After pointing out the traditional end to an otherwise very original ceremony, Dronke continues: “But for the Vic dramatist this was not, after all, the close” (

Dronke 1994, p. 85). He thus seems to think of the text after the new rubric as a part of what he construes as a larger more complex Easter drama. This concerns what he believes to be the earliest known dramatic version of the mentioned

hortulanus episode. However, in a note to the ms. rubric indicating the mentioned Te deum, Dronke writes: “The

Te deum […] serves to demarcate the

Verses pascales from the

Versus de pelegrino. […] we have no evidence from twelfth-century Vic, to my knowledge, about whether the sequel was performed soon after the

Verses pascales, or at a later hour the same day, or on Easter Monday” (

Dronke 1994, p. 107).

Dronke’s point seems to be a literary one: the two ceremonies, possibly or even probably held as distinct events, are part of a unified literary representation of the resurrection event altogether, in which also Jesus as

hortulanus was seen “as another exemplification of his

peregrinus rôle” (

Dronke 1994, p. 108). It was, as is well-known, not unusual for liturgical ceremonies to represent a narrative continuity, as not least the ceremonies of the burial (or

depositio) of the host (or cross) and its resurrection, the

elevatio hostiae (or

crucis), and the

visitatio sepulchri show (for the two first mentioned, see

Young 1933, vol. I, pp. 112–48). What Dronke postulates is fundamentally a literary unity of what, after all, is also a patchwork of traditional liturgical lines importantly including apparently new lines, poetically rephrasing and expanding traditional biblical material.

I shall now focus on the first part of the ceremony (or the first of the two ceremonies), that is what belongs to the headline

Verses pascales. Karl Young altogether considered the manuscript “disordered,” “crudely written,” and “seriously lacerated” (

Young 1933, vol. I, p. 678, n. 6). Among other things, he points to what he believed was a wrongly placed rubric on (fol. 58v), the “Dicxit angelus”.

| Verses Pascales de III Maries | Easter verses of the three Maries |

| Eamus mirram emere | Let us go to buy myrrh |

| Cum liquido aromate, | with liquid spices |

| Vt ualeamus ungere | so that we may anoint |

| Corpus datum sepulture. | The body due for burial. |

| Omnipotens Pater altissime, | Almighty Father, highest one, |

| Angelorum rector mitissime | gentlest ruler of the angels, |

| Quid facient iste miserime! | What shall these most wretched women do? |

| Dicxit angelus | An angel says: |

| Heu, quantus est noster dolor! | Alas, how great is our grief! (Dronke 1994, p. 92) |

Additionally, Dronke in his edition indicates that all these verses were sung by the Maries, not by an angel, simply leaving out the quoted rubric (

Dronke 1994, p. 92). Altogether, in his discussion of the ceremony, he argues from a point of view of dramatic coherence, a point of view much in line with Young. As already stated, the notion of drama in the context of the early

visitatio sepulchri ceremonies is problematic. It seems advisable to try to understand the text with rubrics and music as it stands, at least as much as at all possible. Indeed, no extant rubric can be taken to indicate any action. This does not preclude that such action could have been carried out, but it certainly does not point to it. Otherwise, there are a few attributions of lines to narrative figures, the Maries, Maria (Magdalen), the merchant, and an angel. While the Te deum may be taken as a clear marker of an end to a ceremony called

Verses pascales, this should probably, rather than as a drama, be thought of as what the rubric states, simply verses, sung lines about the resurrection, sung by various figures. This was apparently also how it was understood in the fifteenth century when the rubric was added.

The strange disappearance of the musical (Aquitanian) notation in the middle of a word (at the end of a line, the word “men-

te” on fol. 59v) for the remaining page and its return at the beginning of fol. 60r will be considered below (see

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). In addition, fol. 59v features some very small rubrics among the words without musical notation, consisting simply of the letter “a” in red, put in above the text in four places. Gros believes them to be rubrics abbreviating “angelus,” whereas Karl Young indicates that he cannot explain them (

Gros i Pujol 1999, p. 217;

Young 1933, vol. I, p. 679, n. 7, and 680, n. 1). While Gros does not argue for his reading of the a’s, Dronke (again) argues from a point of view of drama, pointing out that it makes sense in a dramatic context to have the angel sing those particular lines. It would, however, also make sense to have the Maries sing them all (see text and translation in

Dronke 1994, pp. 94–97). Dronke’s use of pronouns in the English translation (as is natural), however, supports his reading more than does the Latin text, as in the following example:

| [Maria:] […] | |

| Licet, sorores, plangere, | Sisters, it is right to mourn, |

| Plangendo Christum querere, | mourning to look for Christ, |

| Querendo corpus ungere, | looking to anoint his body, |

| ungendo mente pascere. | Anointing to feed on it with the mind. |

| A<ngelus>: | Angel: |

| De fletu, viso vulnere, | In weeping as you see the wound, |

| dilecto magno federe | to the loved one, in a great love-bond, |

| cor mostratur in opere. | by your action, your heart is shown. |

| <Maria:> | Mary: |

| Cordis, sorores, creduli […] | Sisters, let us be of trusting […] |

| (Dronke 1994, pp. 94–97) |

Dronke’s reading of the a-rubrics also implies that the angel will sing the line “nostra, surge, sureccio!” (

Dronke 1994, pp. 96–97), by Dronke rendered “arise, our resurrection!” This is a wording not easy to imagine as a line for an angel. Based on Dronke’s reading, one also wonders why there are no similar red “m”-rubrics on fol. 59v for the Maries. While it seems difficult to give a sensible explanation for the a’s, Dronke’s attempt to let these small rubrics support his (anachronistic) understanding of the ceremony as a drama demonstrates the danger in pre-meditated genre interpretations for ceremonies at a time where what is going on rather seems to be creative liturgical experimentation (with no fixed genres involved).

Donovan—as Young—has no explanation for the small a-rubrics. However, he describes in more detail his understanding of the ms. as it resulted from deleting text and inserting new text, pointing out that

the text which originally occupied fol. 59v and the bottom of fol. 59r […], has been erased, and replaced by this later version. This is clearly indicated by the lacerations and thin spots in the folio. It is doubtless no coincidence that the lines which bear mark of erasure […], constitute an independent unit in the piece: all are rhyming eight-syllable verses. The scribe began writing the music for the newly added verses at the beginning of the folio, but he soon realized he could not fit the entire addition with the music in the remaining space. Accordingly he desisted giving the musical notation and proceeded to bunch and abbreviate his words. On the following folio the musical notation begins once again.

Due to the state of the manuscript, especially fol. 59v, there are minor divergences between the textual transcriptions of Gros, Dronke, and Donovan (who generally follows Young). This, however, does not affect the point I want to make. The text that Donovan discusses in the quoted passage—mainly crammed into fol. 59v (

Figure 3, but beginning at the bottom of fol. 59r)—together with the above cited beginning of the

Verses pascales, includes a dialogue between the Maries and the merchant, and (possibly) an angel. It constitutes a poetic unit in its own right, dealing with the biblical Maries, their sorrow, and their wish to bring ointments to Jesus in his grave. In the manuscript context, it introduces, but is otherwise not clearly connected to, the brief and much more traditional

Quem queritis dialogue, which follows (on fol. 60r, see

Figure 2) after the mentioned erasure and the mentioned newly inserted poetic verses. The clearly more traditional

Quem queritis text that begins here opens with the words “Ubi est Christus, meus dominus et filius excelsi? Eamus videre sepulcrum” (“Where is Christ my Lord, the son of the one on high? Let us go to see the sepulchre” (also found on fol. 2r as the beginning of a trope for the introit to the Easter Day mass), and then continues with the dialogue between Maria and the angel, announcing the resurrection, concluding with Maria singing “Alleluia! Ad sepulcrum residens angelus nunciat resurexisse Christum!” (”Alleluja! The Angel sitting at the sepulchre proclaims that Christ has risen” (

Dronke 1994, pp. 98–101), also found in the trope on fol. 2r (see also

Gros i Pujol 1999, p. 161).

This

Quem queritis dialogue then seems to be a self-contained unit, not necessitating what amounts to the comparatively much longer poetic introduction. Donovan’s discussion of the erasures and insertions of new text is convincing, but also raises the question of whether the new poetic introduction was indeed meant to introduce the

Quem queritis ceremony that follows, or whether it could be the case that the poetic verses about the Maries and their preparations to go to the grave on Easter morning were thought of as the beginning of a completely new—much more elaborate—poetic rendering of the biblical narrative about the Maries on Easter morning. In any case, it provided an innovative poetic expansion of Mark 16:1–2, possibly the first ever (

Dronke 1994, p. 83, unnecessarily, however, claiming it to be drama). As pointed out by Donovan (in the above quoted passage), the lack of musical notation for a large portion of this poetic text was a consequence of using an older manuscript for its insertion. The scribe realized along the way that there would not be room for the musical notation if he were to squeeze in his text. Thus, he discontinued the musical notation to get space enough for the words. However, once he was past the new insertion, the music, of course, was included again (it had not been erased). Thus, one could reasonably speculate that what we have are two more or less independent ceremonies under the headline of

verses pascales.

However, the graphics on fol. 59v bottom and fol. 60r top seem to indicate that the space in the bottom of fol. 59v and until the new beginning with “Ubi est Christus” on fol. 60r (see again

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) was not just a blank space. The scribe put in the first words of the beginning of the

Quem queritis ceremony, “Ubi est Christus meus dominus,” the cue for the traditional ceremony on fol. 60r, before the graphics on fol. 59v bottom. He then filled in the remaining space on fol. 59v with graphic scribbles, also including the space before the musically notated “Ubi est Christus” on the first line of fol. 60r, thereby making it clear that the end of the poetic verses expanding Mark 16: 1–2 was indeed supposed to lead straight into the

Quem queritis dialogue. Whether this was the intention of whoever composed the poetic verses is impossible to know. However, the graphics rather clearly seem to indicate that this was at least the intention of the scribe who put in the new poetic ceremony.

Since there are no indications telling us when the ceremony was to be performed during Easter, we cannot know. To what extent there may have been action and division of roles between singers is also unknown. Some lines are explicitly and clearly assigned to Maries, Maria (Magdalen), and the Angel, but for the most part even that is not consistently carried through. What we have here, is a partly innovative text for use at some liturgical ceremony at Easter, likely Easter Matins (because of the Te deum). In a literary sense, it may well be connected also to the part with the headline Versus de pelegrino, but the clear separation with a new rubric makes it doubtful that these two parts belonged in the same ceremony. What is completely clear, however, is that we have an example of a poetic re-writing of an older ceremony, in which a new composition (text and melody) was supposed to replace an older part, seemingly expanding and radically changing what was there before. This new ceremony was then combined with a more traditional Quem queritis ceremony in the manuscript.

Altogether, these manuscript pages bear witness to creative work with biblical material for liturgical use, unconcerned about changing traditional texts, seemingly focusing on creating a vivid and convincing, probably even emotional, impact through the representation of the women coming to the tomb of Jesus. It may well have been part of the previously discussed sacramental technology, meant to let the congregation present at the ceremony be spiritually transferred to an original place and time, to witness the actual biblical women arriving at the grave on Easter morning. However, the overall context of the ceremony is not given in the manuscript, thus here such a thought can only be speculation. It will also be only a speculative but, as it seems, likely scenario that the earlier described flux in the understanding of what was sacramental and what was not in the early twelfth century may have contributed to the involved liturgical freedom, a freedom to change a previous similar kind of ceremony with the same intended function of letting the congregation witness the sacred event of Christ’s resurrection.