Abstract

This article links the feminist debate on women’s land rights in India to the current academic debate on critical human-nature relationships in the Anthropocene by studying how married Hindu women weigh the pros and cons of claiming land in their natal family and how they practice their lived relatedness to land in rural Udaipur (Rajasthan, North India). The article disentangles the complex issue of why women do not respond eagerly to Indian state policies that for a long time have promoted gender equality in the domain of land rights. In reaction to the dominant feminist debate on land rights, the authors introduce religion and more-than-human sociality as analytical foci in the examination of women’s responsiveness to land legislation. Their ethnographic study is based on fieldwork with married women in landowning families in four villages in Udaipur’s countryside. The authors argue that women have well-considered reasons not to claim natal land, and that their intimate relatedness to land as a sentient being, a nonhuman companion, and a powerful goddess explains the women’s reluctance to treat land as an inanimate commodity or property. Looking at religion brings to the fore women’s core business of making land fruitful and powerful, independent of any legislation. The authors maintain that a decolonized perspective on women’s land relatedness that takes religion and women’s multispecies perspective seriously may also offer a breakthrough in understanding why some women do not claim land.

Keywords:

land; land rights; gender; religion; kinship; interspecies relatedness; India; ethnography 1. Introduction

This article links a long-lasting feminist debate on women’s land rights in India to the current debate on critical human-nature relationships in the Anthropocene. By studying Hindu women’s views on their (political and jural) rights to land in the context of their (economic and religious) relatedness to land in rural Udaipur (Rajasthan), we aim to disentangle the complex issue of why women do not respond eagerly to Indian state policies that promote gender equality in the domain of land rights. We consider land ownership of critical concern in times of anthropogenic climate change: global processes of environmental degradation interlock with local processes of capitalist land grabbing and rural gentrification, to generate an increasing scarcity of fertile land in rural Udaipur. Moreover, women are the ones who mostly care for this vulnerable land—considered at once a mother and the goddess Lakshmi. We believe it is important to study women’s lived relatedness to land, and to bring a religious and more-than-human perspective to the fore that has been neglected in feminist debates on land rights in India (e.g., Agarwal 1994; Chowdhry 2017; Jackson 2003; Jacobs 2017; Kowalski 2021; Mathur 2017; Rao 2005a). These debates strongly adhere to the Cartesian alienated concept of nature as a “property” or “resource,” and as such overlook the Indian gendered and cosmological perception of nature as a feminine force that is connected with all living beings (e.g., Shiva 2016). By showing how a specific group of women nurtures and animates the land, thereby creating profound feelings of belonging to that land, our ethnographic study supports the central claim of this Special Issue, that gender and religion need to be taken seriously in the study of human-nature relationships in the Anthropocene.

Taking women’s perspectives on land rights and on an enchanted natural environment into account, we will answer the central question: why do women rarely respond to Indian state policy on gender equality in land legislation and remain reluctant to claim their rights to land? This question overlaps with the main concern of Indian (secular) feminist scholars in the land rights debate, but will be answered by using a different lens. Scholars in the existing debate point mainly at women’s continuing subjugation to men in Indian society, particularly the patrilineal family, to explain women’s reluctance to claim land (e.g., Agarwal 1994; Chowdhry 2017; Mathur 2017). News coverage and online reports on women’s land rights in India (to which these scholars also contribute) correspondingly underline women’s structural submission to male relatives. With headlines such as “Women are being denied the right to inherit land in India” (George 2013) and “Forced by tradition to give up inheritance” (Chandran 2016), media reporting reinforces the image of Indian women as victims of interrelated discriminatory cultural practices: arranged marriage at young age, a “deep-rooted patriarchy,” son preference, and illiteracy or low levels of education that prevent women from being well-informed about their rights as Indian citizens. According to this strain of analysis, being unable to resist family pressure leaves women forced to relinquish their claim on ancestral property. Media report that, for fear of causing conflict in the family or being disgraced in public, “women are made to forgo their claims” and “will never go to court over being denied their right to property” (Chandran 2016). International media platforms on global development also state that women’s ownership of land would “impact India’s ability to climb out of poverty,” but that, unfortunately, such a move remains “a forbidden dream for many women in India” (Devex 2013).

We believe that this dominant debate implicitly supports an anthropocentric capitalist worldview, in which private property and the exploitation of nature are the foundation of economic development and prosperity. Domination by a postcolonial development ideology means that this debate has a blind spot with respect to interspecies mutuality as relatedness and care. The debate also implies a western liberal feminist worldview, in which legal equity, individual autonomy, and empowerment are foundational to women’s liberation from male dominance. Our study finds that land rights feminists who consider land a resource for increasing income and individual empowerment are likely to reproduce a capitalist nature-culture divide that ignores women’s intimate entanglements with land. Additionally striking is the fact that religion, which is vital to Hindu women’s everyday lives, remains completely overlooked in the dominant gender and development debate. We remedy this oversight by introducing religion and more-than-human sociality as analytical foci in our study of women’s responsiveness to land legislation.

Our approach is to begin with studying women’s own perspectives on land claims, as these have been given scant attention in the literature (cf. Rao 2005b, 2017). Second, we stay close to women’s lived relatedness to land by considering their acknowledgement of interspecies kinship and economic collaboration beyond the human. The women in our study consider land an enchanted, agentive, and sentient being, rather than an object or economic resource to be inherited and used. Women’s equal and mutual relationship with land contrasts sharply with the hierarchical and exploitative human-land relationship implied in the debate on land rights and economic development. Central concepts in our perspective will thus be “sentient ecology,” rather than “capitalist economy” and “companionship” with land, rather than its “ownership” and “control”. In line with Radhika Govindrajan’s belief that “a de-colonized anthropology must take into account the multispecies perspective of its interlocutors” (Govindrajan 2018, p. 6), we maintain that such a decolonized perspective on women’s land relatedness can force a breakthrough in understanding why women do not claim land.

We will take three steps to answer our central question and to come to our conclusion that women’s “ownership” of land in patrilineal rural societies can be established through practices other than “traditional” kinship rules or “modern” land legislation, and that, from a women’s perspective, claiming land is not, by definition, a liberating strategy. In the first section, we will review the literature on women and land rights in India to present the dominant debate we are challenging. In the subsequent two sections, we will turn to our ethnographic research with married Hindu women of the landowning population in four multicultural (caste, class, ethnicity, and religion) villages in the rural-urban fringe of Udaipur (Southern Rajasthan). Section 2 will explore how women weigh the pros and cons of making a legal land claim in their natal family. Then in Section 3, we turn to religion to explore how the agencies of other-than-human persons matter in enhancing women’s empowerment and status in the family.

2. Materials and Methods

Our ethnographic study took place against the background of 12 years of recurrent anthropological research on gender, religion, and kinship in the same region of India. Notermans’ long-term involvement in women’s lives in Udaipur and nearby villages, which began in 2008, has continued with yearly revisits, totaling 19 months of fieldwork. This commitment has enabled her to build up relations, combine insights from different social and economic domains, and take multiple perspectives and conflicting views into account. The particular woman-land relationship we examine here was studied in Havala and Badi, two villages nearby Udaipur, from 2017 till 2019. Notermans did (participant) observations of women working in the fields and performing various religious rituals to enchant and honor the land. These observations were combined with small talks, informal conversations, interviews in combination with photo elicitation, and household surveys (see Notermans 2019). In 2019, Swelsen joined Notermans’ research in her final Bachelor project of the Cultural Anthropology and Development Studies program and explored women’s attitudes towards land legislation in the same and in two more villages: Nayakheda and Bhuwana.1 Her ethnographic methods included small talks during (participant) observations, informal conversations with individual women, and structured focus group interviews with five to seven women. Besides small talks regarding women’s relatedness to land, we spoke to a total of 30 women during in-depth and photo-elicitation interviews.

Our focus was not on landless or otherwise marginalized women (widowed, abandoned, disabled or without supportive brothers), whose perspectives might be different from the Hindu women we studied. The women we spoke with were relatively privileged due to their marital status in landowning families (with different ethnic and caste backgrounds: Bhil, Brahmin, Rajput, Sutar, and Teli). We worked with (female) interpreters, who translated between English, Hindi, and the local language, Mewari. With permission of the women interviewed, some of the structured conversations were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim; other conversations were, like the informal talks, reconstructed in written accounts immediately after fieldwork events. Photographs and videos helped us to re-create our observations, to evoke meaningful particulars, and to recollect the sequence of ritual actions. We then built and analyzed our qualitative data using a qualitative grounded theory approach (Emerson et al. 1995; Glaser and Strauss 1967). Spradley’s (1980) domain and taxonomic analyses were particularly helpful when it came to discovering theory on gender and land rights in our fieldnotes and in other qualitative data. To sharpen our analytic proposition for this article, the collective set of data was analyzed by Notermans, the first author.

3. Women and Land Rights in the Literature—Why Do Laws Fail?

The women-land connection is a crucial one in India, as agriculture is the largest livelihood provider in the country, and contributes substantially to the Gross Domestic Product (National Portal of India 2021). More than 70% of India’s population lives rurally and derives a significant portion of its income from agriculture. The Indian anthropologist Akhil Gupta considers the development of agriculture “a critical link in the forging of India as a modern nation” (Gupta 2000, p. 34). In its modern manifestation, Indian agriculture is also highly feminized: the share of women among the total number of farmers increased from 38% in 2000 to 75% in 2012, partly in response to men’s migration to urban centers (Pattnaik et al. 2018, pp. 138–39). With men (temporarily) leaving the village for waged labor in the cities, the proportion of agricultural work undertaken by women subsequently increased (Srivastava 2011). That said, despite the national land legislation, these developments do not go with an increase in women’s land ownership: fewer than 10% of women farmers own land, and these women are said to be unable to control their property (Mathur 2017, p. 297). This nationwide development of men migrating to cities, leaving women in charge of the agricultural work on plots of land they do not formally possess, also portrays local realities in Udaipur’s countryside.

In Rajasthan (India’s largest state), and North India more broadly, women’s land relatedness is first and foremost determined by patrilineal and patrilocal kinship rules. These rules prescribe that only sons inherit family land (and other immoveable property), as they are supposed to stay in their parents’ compound after marriage. By contrast, daughters receive dowry (moveable property such as golden jewelry, luxury dresses, furniture, household items, and vehicles) upon marrying, as they will join the household of their husband and in-laws. Due to village exogamy and caste endogamy (women marrying into same-caste families mostly living miles away from their natal family), the marital household is usually perceived, initially at least, as a household of strangers. Daughters-in-law are expected to follow the rules of the new household and to be of service in domestic and agricultural work, at least in the beginning. The women will gradually move into more powerful positions once they bear children, grow to maturity, gain mastery of the religious repertoire, and accordingly, assume religious authority in the household. From a legal and (western-based) feminist perspective, these kinship rules are often considered discriminatory: they are seen as subjugating women by granting rights and authority to men only. Women do not own land, in neither their natal nor their conjugal family, and thus rely on male relatives (brothers and husbands) for access to land, security, and place belongingness.

To combat this gender inequality in India’s civil society, women were granted legal rights to inherit land by the adoption of the Indian Constitution in 1950 (Chowdhry 2017, p. 2). Since then, the Indian government has been committed to safeguarding the rights and privileges of women, and to implementing additional progressive acts. The Hindu Succession Act of 1956 enabled women to inherit as daughters and sisters and not only as widows, and the amended Act of 2005 granted women equal rights in all property, including agricultural land. This Act also made daughters, married or unmarried, equal to sons in joint Hindu family property (ibid., pp. 5–7; Bates 2004, p. 124). At the international level, the government signed the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), adopted in 1979 by the United Nations (Mathur 2017, p. 297). With this shift, Chowdhry states, “the government reasserted its commitment to remove discrimination against women in all forms, including the legal sphere, by suitably modifying gender-biased laws” (Chowdhry 2017, p. 2). These policies endorse women’s rights to land ownership and deliberately support women in defending their “individual rights” and in circumventing the “traditional rules” of inheritance.

In Rajasthan, state policies have also stimulated women’s land ownership. Rajasthan is India’s largest state and has, despite its arid climate with low and irregular rainfall, a primarily agrarian economy (Mathur 2017, p. 298). With land the most important economic resource, gender equality in landownership remains a critical issue. The most important land right reforms were ushered in by the Rajasthan Tenancy Act (1955) and the Rajasthan Land Revenue Act (1956), which assigned Hindu women the right to inherit land from their father, husband and son (ibid., p. 302). Moreover, beginning in 2000, the government of Rajasthan introduced subsidies promoting women’s access to land, such as the 50% reduction in the stamp duty for agricultural land registered in the name of a woman (ibid., p. 305). Nevertheless, a wide gap still persists between “constitutional guarantees and ground realities” (ibid., p. 308); specifically, women rarely respond to gender-sensitive land legislation by claiming their rights to land.

3.1. Indian Scholarship on Gender and Land Rights

To explain women’s lack of response to land rights legislation, Indian feminist scholars tend to criticize the patriarchal family as an arena of gender-based oppression. Conceiving of development as the equivalent of western modernization, such scholars argue that changes in society have not kept up with the significant changes that have taken place in the legal sphere. Persistent patriarchal practices would exclude women from property, and thus, from socio-political and economic power, and prevent them from making autonomous claims on land (e.g., Agarwal 1994, 2003a; Mathur 2017, p. 310; Palriwala 1996, p. 191; Sharma 1980, p. 13). From this vantage point, it is structures of gender inequality within patrilineal and virilocal families that are the main sources of “women remaining dependent upon men in spite of legislation” (Sharma 1980, p. 40).

Inspired by early western feminist scholarship, anthropologist Ursula Sharma was the first to examine women’s access to property in North India. In her monograph, Sharma (1980, pp. 39–40) writes:

In relation to property, women are defined as dependent because they only have access to the most important forms of wealth-producing property via their relations with men. Women are largely disqualified from exercising direct control over the most important form of property (land) by inheritance rules which favor male heirs, and this disqualification is related to their roles as wives and sisters. A good sister does not claim the land which her brother might inherit. A good wife participates in the control which her husband exercises over any land he may own, but does not command rights in land independently of his family.

Nearly fifteen years later, Bina Agarwal, Indian development economist and expert on rural change and women’s land rights in India, launched the debate on women and land ownership with her groundbreaking monograph, A Field of One’s Own: Gender and Land Rights in South Asia (Agarwal 1994). This pioneering and still highly cited work is based on comparative literature research, Agarwal’s own fieldwork in North India (particularly Rajasthan), and discussions with social activists in the five South Asian countries (ibid., p. 47). The book introduces Agarwal’s central and deeply moving argument that women’s legal land ownership is “the single most critical entry point for women’s empowerment in South Asia” (ibid., p. 2). Inspired by western feminist activism, Agarwal became strongly involved in the women’s movement in South Asia, fighting for the idea that development is not gender neutral and therefore needs to be examined through the lens of gender (ibid., p. 4). Many more of her publications followed, and from the mid-1990s onwards, other socio-economic scientists joined the debate on women’s response to Indian state policies on land rights (e.g., Agarwal 1994, 2003a, 2003b, 2005; Bates 2004; Berry 2011; Chowdhry 2017; Jackson 2003; Mathur 2017; Rao 2005b, 2018).

Agarwal (1994, p. xv) considers women’s land ownership the necessary condition for being liberated from kin persons and becoming independent citizen subjects:

Land has been and continues to be the most significant form of property in rural South Asia. It is a critical determinant of economic well-being, social status, and political power. However, there is substantial evidence that economic resources in the hands of male household members often do not benefit female members in equal degree. Independent ownership of such resources, especially land, can thus be of crucial importance in promoting the well-being and empowerment of women.

In a later study, Agarwal repeats that “women’s land ownership is likely to have positive effects on women’s and their family’s welfare, agricultural productivity, poverty reduction and women’s empowerment” (Agarwal 2003a, p. 218). Twenty years later, but still fully consistent with Agarwal’s ideas, Pem Chowdhry (2017, p. 1) opens her edited volume on gender discrimination in land ownership by asking: What does empowerment of women entail? She answers (ibid.):

It means gaining control over sources of power like material assets and self-assertion, and ability to take part in the making of decisions that affect their lives. For this, women must have equal opportunities, equal capabilities, and equal access to resources. Such a manifestation would ultimately mean a redistribution of existing power relations and finally a challenge to the patriarchal ideology and male dominance, as the concept of women empowerment is associated with gender equality.

Agarwal (1994, p. 249) states that women in “traditionally” patrilineal communities rarely realize their legal rights because “custom still dominates practice”. Women would give up their claims in parental ancestral land in favor of their brothers for a mix of reasons, such as: maintaining access to the natal home and village; keeping up a good relationship with sisters-in-law, and particularly brothers, with whom the women have emotional and ritual ties, and from whom they may expect to receive lifelong social, material, and ceremonial support; also in situations of marital distress, severe illness, or widowhood (ibid., pp. 260–65). Though Agarwal here correctly points at women’s much-valued intimate and solidary bonds with brothers, she does not consider these “traditional” interdependencies as beneficial for women. Rather, she sees them as obstacles that thwart women’s path to development and liberation and, consequently, need to be removed. Agarwal thus accuses the patriarchal family at the micro level of preserving customs that discriminate against women, and restrict them when it comes to exercising their legal claims.2

Though we appreciate Agarwal’s feminist motive for gender equality in land rights, we believe that her analysis fails to explain women’s reluctance to claim land: her approach is biased towards a nature-culture divide and by an emphasis on individual autonomy, both which are typical of western development and feminist ideologies; her approach then is timebound, that is, it does not reflect changes in academic feminist theory that emphasize intersectionality (e.g., Moore 1994), relational personhood (e.g., Carsten 2004), and kinship beyond the human (e.g., Bird-David 2018; Govindrajan 2018; Haraway 2003). In addition, Agarwal’s approach overlooks the global and historical processes that influence power inequalities at the local level. Some of this criticism is mentioned by anthropologists working on gender and kinship (Jacobs 2017; Kowalski 2021; Jackson 2003; Rao 2005a, 2005b, 2017), and we will briefly review their work, as it approximates the insights we gained from the farmer women in rural Udaipur. That said, a focus on religion and more-than-human sociality is also missing, even in this scholarship.

3.2. Dissenting Voices in the Women’s Rights Debate

A recent study by anthropologist Julia Kowalski states that scholars in the feminist land rights debate seem to be stuck in “the discursive economy of women’s rights” (Kowalski 2021, p. 330). The women’s rights discourse, she states, is built on the premise that (1) women should be encouraged to cultivate and defend their individual desires in opposition to men, and that (2) gender and kinship are also in opposition to each other (ibid., p. 332). Women’s rights discourse, she states, reproduces a distinction between gender and kinship that stands for multiple other distinctions: between individual and family, modernity and tradition, civil law and customary law, freedom and patriarchy, rights and repression, progress and backwardness. “The distinction between gender and kinship,” Kowalski states, “relies on longstanding liberal representations of kinship-based societies as primitive, in contrast with modern societies” (ibid., p. 332). Women’s rights discourse would then use this contrasting set to present kinship—often glossed as patriarchy—as a locally grounded, backward, and static structure that reproduces inequality, and gender, by contrast, as a global and progressive category that would liberate women from kinship’s suppression of their independence (ibid).

Women’s rights projects, Kowalski (2021, p. 333) states, thus rely upon western narratives of modernity and development, and promote a liberal discourse that imagines that individual autonomy requires independence. In this scenario, social progress would only happen when individuals are liberated from the constraints of social roles. Such a political theory of liberal personhood assumes individuals to be both less modern and less free when the demands of kin relations, rather than independent choice, appear to shape behavior. These “civilizational distinctions” between so-called kin-based societies and modern individuals circulate globally and reproduce the figure of Indian kinship as backward and static, the Indian family as a site of harm and struggle, and patriarchy as the source of women’s confinement and suppression (ibid., p. 334). Women’s rights discourse thus encourages women to cultivate their individual desires, while women, as Kowalski notes in her work with North Indian NGOs, often desire better relations with their families. To sustain these relations, women rather “adjust” their individual desires to the demands of kin, a strategy that, analytically at least, conflicts with the goals of women’s rights (ibid., p. 331).

Kowalski’s plea to step out of the dominant economic development discourse to do justice to women’s lived realities and their own perceptions of what is right, resonates with the studies of legal anthropologist Karine Bates (2004) and comparative sociologist Susie Jacobs (2017). Explaining the gap between land legislation and grassroots initiatives, Bates and Jacobs point to postcolonial influences on Indian land rights policies, rather than to harmful local kinship practices. Bates declares that British common law and western philosophy shape the concept of equality in national laws concerning the personal rights of the Hindu population (Bates 2004, p. 123). She states that “although the principle of individual rights entrenched in the Constitution may be inspired by a Western legal tradition that associates equality with individualism, the concept of equality in India may be different” (ibid). In the Indian context, equality would not always refer to sameness, individual autonomy and self-interest, but rather to a respectful recognition of difference and relational interdependence.

Susie Jacobs (2017) also points to the postcolonial processes at stake in the land rights question and states that “through neoliberal global policy, the main recent international trend in land and agriculture has been the move towards privatization and titling of land”. This trend, she says, does not necessarily affect men and women in the same ways: “Where land is privatized and owned outright, women are significantly less likely to possess it formally” (ibid., p. 323). Land titling, in her view, thus creates rather than eliminates gender inequality. Jacobs maintains that, more than a gender equity policy, land titling is a central pillar of contemporary neoliberal development policy, which ostensibly prompts growth and reduces poverty (Jacobs 2017, p. 324). The premise of this assumption is that land titling would stimulate investment on farms, and make land easier to buy and sell; in theory, that would raise its financial value. From such a neoliberal perspective, Jacobs states, communal tenure is seen as both a barrier to investment and a site of traditional values that impede any improvement of progress (ibid., p. 325). Nitya Rao (2017, p. 23) even places the origin of land titling back in the colonial period, when individual land titling became a strategy for revenue collection and enhancement by the colonial government in India, with defaulters effectively losing their land. Similar to Jacobs (2017), she notices that individual land titling then continued post-independence, “particularly at the instance of the World Bank since the mid-1970s, as a strategy for agricultural growth and development” (ibid).

Kowalski (2021), Bates (2004), Jacobs (2017), and Rao (2017) thus situate the problem at the global rather than local level. They point the finger of blame at colonial and postcolonial policies, political theories of liberal personhood, neoliberalism, and World Bank subsidies that, taken together, diffuse powerful ethnocentric assumptions about what is right and empowering for women. While our study deliberately focuses on the local level to adjust incorrect assumptions about women’s disempowerment in families and their reluctance to claim land, we believe these ethnocentric assumptions also deserve our critical attention as they might turn around the value hierarchies of “civilizational distinctions” (Kowalski 2021, p. 334): instead of accusing so-called traditional patriarchal customs of doing “violence” and “harm” to local women, western colonial and postcolonial interference may be the culprit of social injustice at the grassroots level.

Before we consult women’s perspectives in the villages studied, we pay some attention to the work of Cecile Jackson (2003) and Nitya Rao (2005a, 2005b, 2017), both scholars arguing for a gender approach that is context-specific rather than prescriptive and generalized. Jackson (2003) criticizes Agarwal (2003a) for not ethnographically exploring the variety of women’s lives and their different and changing positions in patrilineal households. Jackson suggests that women’s choice not to claim land could be quite deliberate. She reveals that women’s interests do not necessarily conflict with those of their male relatives. Women may even share interests with male relatives, and have conflicting interests themselves. “As a daughter,” Jackson (ibid., p. 467) states, “a woman may have the interest in claiming a share of parental property, but as a wife she may also be against the land claims of her husband’s sister, and as a mother she will not necessarily support a daughter against the claims of a son”. These intersecting interests reflect the multiple subject positions each woman occupies and entail, according to Jackson, a diversity of women’s opinions on the desirability of land rights, rather than presupposing universal support from women as argued by Agarwal.

We agree with Jackson’s (2003) view that women’s multiple subject positions and their solidary relationships with husbands, brothers, and sons make a move to claim land in the natal or conjugal family less obvious and desirable than land rights scholars and activists suggest. Where the women’s rights discourse creates a gender divide, women are more likely to unite and to invest in their relationships with male kin. Indian women often do not have a strong sense of individual interest or well-being (Jackson 2003, p. 473). Related to their multiple subject positions, women rather perceive their well-being in terms of the well-being of family members; their own well-being is thus profoundly affected by the well-being of those they care for, collaborate with, or depend on. In line with Jackson, Rao (2005a) points at the mutuality and interdependence between men and women, and distances from Agarwal’s assumption that women are victimized by men in patrilineal families. Women, according to Rao, do not see the household as a site of struggle and competing interests, but as a site of mutual complementarity (ibid., p. 371). Land, she says, is, for women, a joint resource which can only be productive when reciprocity and interdependency between men and women are valued and practiced (ibid., p. 358).

Shared motives rather than individual self-interest are central to women’s lives in farming households and are consonant with the findings in our study. We believe that western-based liberal feminism, so passionately defended by Agarwal (1994), will not adequately explain why rural women do not claim land. In line with Jackson (2003) and Rao (2005a, 2017), we argue that women’s relational personhood and their multiple subject positions should be considered when trying to understand why not claiming land might be the preferred choice, rather than the result of being in a victimized position in a male-dominated household. We will turn to all this in our next section.

What is still missing in the feminist anthropological work of Jackson and Rao are women’s religious activities and their interspecies relatedness to land. We maintain that we should look beyond the human, and integrate into our analysis what the women so willingly integrate in their social network: land as a nonhuman person, or companion, with whom they intimately bond and whom they enchant during their everyday activities. We will explore this in our last section, then complement what women say about their lived relatedness to land with what they do with land, not as a natural resource but as a sentient being that demands women’s care and solidarity, and who, in return, imbues them with power and a strong sense of place belongingness.

4. What Do Women Say? Weighing the Pros and Cons of Making a Legal Land Claim

In this section, we explore Jackson’s (2003) suggestion that not claiming land may also be a conscious choice. We interviewed fifteen married women regarding their considerations to claim land or not. The majority (13) of these women, ages 40 to 50 years, were eager to share their opinions. The three younger women were more uncertain and wanted to know what others said first before they would freely share with us. All fifteen women had access to land in both their natal and conjugal family and were well-informed regarding gendered state policies on land rights. We found that none of them had decided to make a land claim. However, this was not because they lacked agency or felt forced by male relatives into this position. These women presented their decision as deliberate, made after carefully weighing the pros and cons of legal ownership. In the argumentations we collected, we distinguish four main reasons for not claiming land: (1) the impracticality of owning land in the natal family; (2) women’s access to land in their conjugal family; (3) the benefits of a good relationship with brothers, and (4) the empathy with land as a living being. In this section, we will illustrate the reasons using select quotes from the interviews, while protecting women’s privacy by using pseudonyms.

Yet, before we turn to our ethnography, we would like to reiterate that we obtained the four reasons for not claiming land from the specific group of married women in our study. As said before, these women represent a relatively privileged group of female farmers: they were born and married into landowning families and were not marginalized in the sense of being widowed, abandoned, disabled, or lacking supportive brothers. We reiterate this to highlight the fact that for other women in other settings in India, these four reasons may not be equally valid. Women in less privileged positions may profit from land titling and legal support in fighting patriarchal family structures that obstruct making land claims (e.g., Rao 2005b).

4.1. The Impracticability of Owning Land in the Natal Family

The first reason for not claiming land in the natal family relates to village exogamy. The women emphasized to us the impracticability of cultivating land that could only be reached by long-distance traveling. Nimla, for example, said: “Why should I want to own that land? I do not want to move back, I have a life here with my husband”. Instead of moving back, she wants to move forward, and that means creating her own family with her in-laws. That is where her future lies, not at her birth ground. Married women only move back to their natal family for special and often festive occasions: to take a break from daily responsibilities and heavy work at home, to spend their holidays, or to celebrate Hindu festivals. This time is considered quality time and is meant for relaxation and indulgence, not for laboring in the fields. The women take off their sari (clothes showing women’s marital status), and resume their position as daughters and sisters, which includes being spoilt with gifts from their brothers.

The interviewed women underline the impracticability of owning remote land by saying that even when they have land, they relinquish it or gift it to their brothers. Ruchika, who has only sisters, said that her father’s land will be divided between his daughters when he dies. Yet, she herself does not want this land: “I live with my husband and my family is here, where I have enough land. I do not want or need my father’s land, it’s not practical”. Lakshima told us: “When my father died, he gave an equal share to his daughters and his sons. As sisters, we collectively decided to gift it to our brothers who live there because we have access to our husbands’ land”.

4.2. Having Access to Land in Their Conjugal Family

Having access to marital land is another reason the women discussed in our conversations. They say they do not need land and thus refuse to claim additional land. Bimla stated: “Why would I take land from my brother when I have land with my husband? My family married me into a good family that takes care of me, why would I make a land claim?” Another woman, Kamal, said: “Parents marry their daughters into families with sufficient resources to provide for their daughters. As long as we do not live in poverty and are taken care of, there is no reason to resort to our natal family and claim their land”. Claiming natal land would thus harm brothers and offend the in-laws.

It is important to point out that, though not de jure owning land in their marital family, women do have access to that land and de facto possess it. Married women cultivate the fields at their in-laws and have almost total control over it (see also: Rao 2005b, p. 737). This arrangement creates a strong sense of belonging to and companionship with that land. The women in our study said that having access to land and interacting with it daily was more relevant than having formal ownership. In other words, protecting their access to land is a more rational, sensible, and empowering choice than claiming individual ownership of land (c.f. Ribot and Peluso 2003).

Notably, when the women in our study said they already had enough land, they also referred to land as a place of belonging. Women’s belonging to natal land differs from a sense of belonging to marital land: the first is given to females by birth and maintained, not by cultivation, but through women’s traveling and their brothers’ gift-giving. By contrast, women’s belonging to marital land is crafted in the soil, through daily farming and ritual care work—a topic we explore in the next section. Though in-married women start as “strangers” in their conjugal household, they immediately build an intimate relationship with land as a nonhuman associate and co-creator of fruitful family life. Through their daily embodied interactions with the soil, women create a deep sense of relatedness and belonging to their marital land. This is why Nimla wondered why she should claim her brother’s land, as she was already settled at her marital land.

4.3. The Benefits of Good Relationships with Brothers

Another reason for not claiming land is that women want good relationships with brothers. While the women mentioned four reasons overall, the first they usually spoke of was kin solidarity. Whereas land titling is based on the idea of individual rights and welfare, the women studied said they do not strive for any betterment when it happens at the expense of their relatives. That would not fit into their perception of “prosperity”. As Anju said: “The wellbeing of my family is more important than money, any property or my own wellbeing”. Women say they do not claim land when they have good relationships with their families. “When claiming my brother’s land,” Anju said, “he would be worse off. My brother and his wife depend on that land, they work on it daily and finance and nourish their household with it. When I claim that land, I rob my kin of their income and their base of living. I will never do that”. Therefore Bina wondered: “Why would I make this decision if I know that taking the land is going to hurt my family?”

Women also say that the benefits that accrue from a good relationship with their brothers by far surpass the benefits of having an extra plot of land. Lavanya said: “I think a woman would only claim land if she has a really bad relationship with her brother, otherwise I cannot imagine it”. By a good relationship, the women were suggesting mutual care. Women showing solidarity with their brothers expect solidarity in return. Lavanya says she needs her brother’s help when problems arise with her husband. In case she wants to (temporarily) leave her husband or should she become a widow, she knows that she can count on her brother to welcome and protect her. Brothers play an important mediating role when conflicts occur in the marital household. Not having their brothers’ emotional and material support strongly disempowers women, and puts them at a disadvantage. While India sees itself as a welfare state, it does not have adequate resources to provide adequate social security; in emergencies, women have only kin to fall back on (Rao 2005b, p. 728). In crises, it is brothers who provide for the women in a family with a reliable safety net. Women then risk that safety net when claiming land.

Another reason why women cherish their brothers concerns their gift-giving. This is central to the sister-brother bond and vital for women’s well-being and emotional comfort. Anju said she regularly visits her brother, who will give her presents, such as clothes, jewelry, household items, sweets, money, or gifts for her children. Women, while they do not materially depend on these gifts, nonetheless value them highly. Gifts express commitment, affection, and respect. Anju expects her brother to continue his gift-giving throughout her married life, as it is part of the dowry she receives from her natal family. Dowry, then, is not a one-off transfer of property at the time of the wedding, rather it entails a lifelong chain of gift-giving. This in turn renews a daughter’s belonging to her natal family, feeds the intimate bond between brothers and sisters, and confirms the value of gender complementarity for a prosperous life. Brothers also make essential contributions to women’s religious ceremonies, especially those that demarcate vital life events and are meant to bring fertility and prosperity. Brothers are expected to pay for these rituals and to be present: indeed, without the brothers’ participation, the ritual would not bring the desired outcome. Taking all these gifts and contributions together, Garima states, women receive more comfort and support than land titling would ever give them. Moreover, claiming land would feel like claiming a second dowry from their natal family, and this would conflict with women’s ethical and practical motivations to keep kin relationships healthy and beneficial—a balance which is also in the women’s interest.

The fourth, but by no means least significant, reason that women mentioned for keeping their relationship with brothers healthy is that their brothers have wives who will be affected by their land claims. Nimla, for example, said: “When I claim paternal land, it will affect me, too. My sisters-in-law will do the same and claim my husband’s land as my husband will have access to my natal family’s land. This is very bad for me. Practically, it is not doable”. Several women voiced that a land claim would lead to a vicious circle of impracticable land claims that “would not solve anything”. Lakshima, quoted above, mentioned that her decision to give her inherited land to her brothers was also inspired by solidarity with her brothers’ wives. She wanted to prevent further land claims in the family. If she decided to keep their share of the paternal land, their sisters-in-law would consider claiming land in their natal family for sustaining family life. This would leave the paternal land uncared-for. The solidarity that women feel towards other women—in this case, their sisters-in-law—thus restrains women from claiming, and does not, as Agarwal (1994) argued, incite them to claim their natal land.

4.4. Women’s Empathy with Land as a Living Being

At the heart of this reason for not claiming land is the desire to save the land from fragmentation. In the women’s view, land is not an inanimate material that can be endlessly divided and exploited. Land, by contrast, must be treated as a sentient being that needs care and whose integrity needs to be protected. In the villages studied, the average size of the fields that families of the landowning castes possess is 1–2 hectares—too small to be divided without losing their life-giving capacities. Land fragmentation would be a violation of the living body of the land; it would threat her fertility. By resisting fragmentation, women are assuming moral responsibility for the living land and for the family nourished by her. Lavanya, for example, stated that she legally owns half of her late father’s land, while her two brothers share the other half. She wanted to leave the natal land intact, and enable her brothers to have sufficient land to feed and support their families.

The women studied are convinced that human and animal life depend upon the vitality of the soil. As a nourishing mother and a powerful goddess, the land cares for the women and their families, and in return, she requires women’s attentive care. Anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose (1999, p. 175) identifies this cycle as an “ethic of connection”: an ethic that takes mutual care in a system of connections, reciprocities, and interdependent responsibilities into account. It is an ethic based on the ecological awareness that “all sentient living beings depend on each other through relationships of care” (Rose 1999, p. 184). The women studied express an awareness of interdependent lives, and consider the human, natural, and divine world to be one entangled world, with humans and nonhumans joined together “through relations of care and mutual subjection” (Govindrajan 2018, p. 40). We argue that women’s choice not to claim land can only be understood when we complement our anthropocentric analyses of kinship with a focus on women’s subjection to, companionship with, and empowerment through this other-than-human world.

The abovementioned being said, women are less likely to articulate their intimate bond with the soil and the associated goddess in verbal statements isolated from ritual action. In the next section, we explicitly focus on religion, and with that, we shift from what women tell about land to what women, in regular ritual activities, do with land.3 Consequently, the findings will not be illustrated with quotes from women’s stories, but with descriptions of observations and with photographs. Together, these bear evidence of women’s embodied communication with the more-than-human world, and support our finding that women’s intimate relatedness with land is primarily expressed in ritual action and daily care. It also supports our claim that studying more-than-human socialites requires our attentiveness to alternative ways of speaking across species. We will return to this in the conclusion, when we present religion as just such an alternative means of communication.

5. What Do Women Do? Caring for Land through Religious Practices

The female farmers in our study support a biocentric worldview that presumes in-depth entanglements of non-human and human agencies. Such a worldview is based on a perception of shared personhood, meaning that agency, consciousness, sentience, sociality, and perspective are ascribed to all living beings and not exclusively to humans. This commonality makes “interspecies kinship” (Govindrajan 2018) possible. The women studied perceive the soil as a nonhuman mother because of her life-giving, nurturing, and protective capacities. Human mothers bear children, mother soil produces food, and together they bring fertility and welfare to the family and the environment. They care for each other in reciprocal ways: the women nurture the soil, and she in turn yields abundant harvest to nurture the family. Through both human and nonhuman mothers flows the ultimate lifegiving power shakti that in Hinduism is conceived of as a divine female energy.

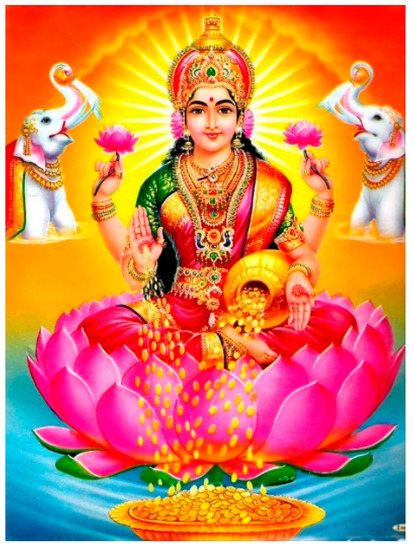

Rather than presuming that empowerment, well-being, and progress exclusively come from the outside—from neoliberal policy, the World Bank, NGOs, or from civil law—the women in our study claim that power comes from other-than-human kin and especially from mother soil. Women’s soil mother is equal to the powerful Hindu goddess Lakshmi, to whom all Hindus and all humans in the household (male and female) bow. As a divine mother, Lakshmi brings prosperity, fertility, abundance of food, and monetary wealth. She also represents feminine beauty and marital fruitfulness and with that, all married women in society. Lakshmi thus also endows human mothers with divine status.

Both married women and mother soil are thus venerated as the goddess Lakshmi. Lakshmi’s main attributes of wealth, riches, charm, and so on are symbolized by golden jewelry and coins (Figure 1). The harvest of wheat from the fields is also considered Lakshmi’s “gift of gold” (Figure 2). Gold is also mainly attributed to married women. The core gift of the dowry that women receive at marriage is a costly necklace (mangalsutra, auspicious thread) of the purest gold that effectively serves as a woman’s bank, her assurance in life, her connection with her natal family, and her investment in her marital family. Gold is the “substance of kinship” (Carsten 2004) that human and nonhuman mothers share; it points to their preciousness and their valuable collaboration in bringing wealth to their society.

Figure 1.

Popular representation of the goddess Lakshmi with her abundant gift of wealth—postcard in private collection of Notermans.

Figure 2.

Wheat harvest in Badi: Lakshmi’s “gift of gold”—photo by Notermans, March 2019.

The women we studied live in close relation to the soil and agriculture; for one thing, there is little differentiation between farm and household. The kinship women feel with the land they inhabit and cultivate is, as Govindrajan states, “rooted in feminized productive practices and care” (Govindrajan 2018, p. 45). With these practices, the women build profound ecological knowledge. Women do the farming with love and emphatic attention, yet describe it as time-consuming and physically exhausting: as hard work. During our observations in the fields, we learned that this hard work was actually practiced as a gift of care for mother soil. Through farming, women activate the power of the soil, and make her fruitful and beautiful. Women’s careful handling of mother soil consists of daily labor and attention, empathically feeling and inspecting her body and temperament, feeding and beautifying her with cow dung, planting her with a balanced mix of wheat, pulses, fruits, herbs, and vegetables, manually digging irrigation canals in her soil, watering and cooling her with fresh mountain water, and taking care of an esthetically beautiful composition when it comes to planting. Women follow the seasonal rhythms for sewing and harvesting, and use local seeds and the manure of fresh cow dung so as not to exhaust mother soil. Recognizing the personhood of land, women approach their field in terms of “giving motherly care” and “creating feminine beauty”. For these gifts of careful attention and beautification, the field reciprocates with food, protection, and prosperity: in sum, a gift of gold.

Women’s rituals for mother soil are part of their physical and emotional care work. In everyday rituals called puja, they ask her for permission to labor the soil, for help and support, they wake her up or let her sleep, make her feel comfortable, praise her power, and always thank her for what she has given. During such prayers, women ring bells to activate the soil, light candles and burn incense, don decorations, and offer milk or sweets to please, beautify, and pamper her. Besides these casual rituals, the in-married women of a household or neighborhood may also unite to do more elaborate rituals of beautification and thanksgiving. For example, at sowing time, women celebrate the generosity and responsiveness of the soil.4 They dress up in their auspicious and colorful marital dresses, sit together and cultivate a field in miniature; their joint attention goes to the soil in the middle of the circle they create with their own bodies (Figure 3). They water the soil, spread seeds, and offer gifts such as flowers, saris, candles, incense, fruits, and flowers. The women also dig coins into the soil, asking Lakshmi to reciprocate with money and wealth. The most outstanding gift is a set of golden jewelry (mainly rings and bracelets), kneaded of yellow-colored dough, to make the soil happy and look beautiful, like a married woman (Figure 4). This soil-focused ritual confirms women’s identification with the soil as a married woman, their intimate companionship, as well as their mutual relationship of care.

Figure 3.

Women caring for mother soil by gift-giving—photo by Notermans, March 2019.

Figure 4.

Women beautifying mother soil with gifts of gold—photo by Notermans, March 2019.

Mutual gifts of gold unmistakeably appear in another fertility ritual during Divali, India’s most popular festival. In autumn, between the harvesting and sowing seasons, the nation celebrates the life-giving powers of human and nonhuman mothers in various rituals devoted to Lakshmi. In rural Udaipur (as across the country, where many variations are found), women craft their intimate relatedness to land in cow dung (Figure 5). In a women-owned ritual called Govardhan puja, married women knead a sculpture out of large quantities of fresh cow dung (the size varying from 0.5–2 square metres) that represents both the local environment (fields, mountains, lakes, plants, trees, and animals) and the human family (a heterosexual couple with children in the womb and cattle in the shed) (Figure 6, see for more details: Notermans 2019). The figure is beautified with grains and sugar cane from the harvest, with milk and all kinds of dairy products, and with (gold) chains of marigolds—all representing the wealth that women and land jointly reproduce. The cow dung sculpture simultaneously celebrates life and female reproductive power. Made at the doorstep of women’s conjugal homes, these organic sculptures confirm in-married wives’ sense of belonging to “their own” place.

Figure 5.

Women crafting their kinship with land in cow dung, Badi, November 2018—Photo by Notermans.

Figure 6.

Cow dung sculpture representing the fertile family and the fertile local landscape, Havala, October 2017—photo by Notermans.

These intimate practices of bonding with conjugal land help us to understand why these women refuse to claim land that is remote and inaccessible on a daily basis. Land they do not dwell in, in which they do not invest their bodily energy, nor enchant with female power, nor shower with gifts to make their mutual reciprocal caregiving work, will never feel like it is “their own,” and will fail to bring that same sense of intimate attachment as conjugal land. Women do not need land titling to get a sense of place “ownership”. That ownership does not come from modern civil law or customary inheritance rules, but from their everyday embodied and ritual interactions with land as a powerful co-mother.

6. Conclusions

In this article, we explored women’s perspectives on land rights and land relatedness to answer the central question: why do women rarely respond to Indian state policy on gender equality in land legislation and stay reluctant to claim their rights to land? Interviewing married women in rural land-owing families and observing them in their daily interactions with land revealed a coherent set of practical, social, economic, and religious reasons that women have for not claiming land. In addition, we noticed that a neglect of women’s everyday entanglements with other-than-human life forms characterizes the feminist debate on gender and land rights. Although the debate did broaden from a focus on women as a homogenous category of women victimized by patriarchy (e.g., Agarwal 1994; Chowdhry 2017) to a focus on women as a differentiated category having agency in multiple and changing subject positions (e.g., Jackson 2003; Rao 2005a), the discussion is still determined by anthropocentrism that, frankly, overlooks the recognition that in women’s views, land is not just an inanimate object to be claimed and used out of self-interest.

Jackson (2003) and Rao (2005a) introduced the concept of women’s relational personhood and the understanding that women’s well-being is profoundly affected by the well-being of the persons they relate to. Our study confirms this: women do not claim land when it hurts their relatives and worsens their mutual interdependencies. That said, what these scholars overlook is that women’s perception of relational personhood goes well beyond the human to include other-than-human beings. For that reason, we added to our focus on women’s relational personhood an awareness of more-than-human sociality, as women’s perception of affective kinship is not confined to the human species. Species is, for women, to use the words of Nurit Bird-David (2018, p. 33), “simply one of an individual’s attributes, alongside sex, gender, class, caste, and age”. Such a species-inclusive perception of personhood enables the women to have interspecies relatedness as well—that is, they perceive land as a person and sentient being, and thus find similarities in the femaleness and mothering of land. This in turn makes women unwilling to treat her (mother soil) as a commodity to be owned and exploited for their own benefits, especially as that would violate their ethical rules and daily practices of mutual care and protection.

We argue that we can only find the answer to women’s reluctance to respond to the well-intended gender-sensitive land legislation in India when we step away from academic anthropocentrism and take into account the multispecies perspective of the women concerned. We concur with Govindrajan’s (2018, p. 6) belief that such a recognition of ontological diversity and (bodily and emotional) affection across species would help anthropologists to decolonize our discipline. This is particularly relevant for the field of mainstream (liberal) feminist scholarship, where a reluctance to reject the nature-culture divide, and to revalue the woman-nature connection still dominates (O’Reilly 2019). Based on the assumption that mothering and caring are natural to women because of their biological sex and reproductive bodies, liberal feminism “views motherhood as a significant, if not the determining, cause of women’s oppression under patriarchy” (ibid., p. 21). This view echoes Agarwal’s feminist stance towards women in patriarchy, in which the feminist solution would be for women “to become like men and denounce motherhood” (ibid.), or, in the context of the debate, to be equal to men, and to claim land rights. Liberal feminism tends to promote gender equality by upholding a nature-culture divide that, in effect, encourages women to shift within the divide from the women’s to the men’s side. Through fieldwork, we learned that a decolonized, and thus positive feminist, stance to mothering and care work and to gender complementarity (rather than equity) comes closer to the perspective of women who perceive the living world as powerful and capable of sharing that power with them.

Comparable to a focus on more-than-human sociality, we included a decolonized understanding of religion in our analyses. As long as religion remains associated with the “supernatural,” with people’s “belief” in god or the divine, and with male-dominated religious institutions, it runs the risk of being overlooked by those who adhere to a modern secular, neoliberal, and feminist worldview. This is certainly the case in the gender and land rights debate. To acknowledge women’s intense involvement with the more-than-human world and to value the empowerment that accompanies this, we need first to decolonize the concept of religion—in effect, release it from its Eurocentric meaning of a symbolic or belief system (Fitzgerald 1997, p. 91) and from the related anthropocentric assumption that culture, nature, and supernature are divided realms (Jackson 2018). For the women in our study, religion is not a belief, nor a symbolic system or delineated field of spiritual activity. Rather, religion refers to an embodied practice of creating deep entanglements with the more-than-human world. Religion, in this sense, is intrinsically part of women’s gendered relatedness to land. As such, women’s modern rural lives are saturated with religion, which in this context points to a deep sense of interspecies relatedness and to the need to relate and communicate across species. Women’s religious rituals of subjection and control, of bonding by care-giving, gift-giving, and beautification are potent ways to speak with the other-than-human world (see also: Stringer 2008). Yet, it is not merely in spoken language but in embodied rituals that women “speak” across species and “translate” one another’s responsiveness. Religion is women’s way of telling the world that they perceive themselves not as autonomous individuals acting out of self-interest but as sensitive subjects enmeshed in human and other-than-human networks of kinship, being continually related to and responsible for other-than-human life forms with whom they live in mutual relationships of submission, empowerment, and responsibility. By re-interpreting religion as an embodied practice of interspecies communication rooted in a relational ontology, and by introducing religion into the gender and land rights debate, we have added an important focus—that of women’s core business of making land fruitful and powerful, independent of any legislation. To understand women’s struggles with the environmental crises of the Anthropocene, we see Jason Moore’s alternative term “the Capitalocene” as more accurate: it draws our attention to the dominant androcentric and capitalist way of organizing nature (Moore 2016, p. 6). We also think that women’s ethical and embodied relatedness to land, often overlooked even in neoliberal and feminist discourses, invites us to reconsider how “sustainable development” should be (e.g., Merchant 2020). Sentient ecologies with cyclical and reciprocal processes of care and gift-giving, together with a moral responsibility towards any person in the natural environment, will likely be more sustainable than the globally still-dominating capitalism that exploits nature and secures monetary wealth for privileged groups of people. Is it too optimistic to ask whether our study on farmer women in rural Udaipur helps point to a new future in “naturecultures” (Haraway 2003), or to “new ways of thinking humanity-in-nature, and nature-in-humanity” (Moore 2016, p. 5)?

Unfortunately, the answer to the aforementioned is yes. The environments of the women we studied are currently under the threat of capitalism. We observed as much in the landscape, and were also informed by concerned male residents. Influential and wealthy estate agents try to persuade women to claim their land and subsequently sell it to the urban rich, thereby profiting from women’s notion of the impracticality of using natal land. Urban elites in Udaipur increasingly confiscate rural land to build second (country) houses, luxury resorts, golf courses, and/or swimming pools for relaxation and economic gain. The disparity in land care is real: while the women know how to use the limited amounts of water available in this desert area, swimming pools and golf courses definitely tax the arid environment. This elite appropriation and misuse of the countryside will in turn destroy women’s precious land, put their livelihoods at risk, and inflict serious harm on the ecology and vitality of the natural environment.

Though follow-up research on this process of rural gentrification is yet to be done, in light of this study and the gender and land rights debate from which it started, we can say that the most serious potential danger of land titling is that it provides opportunities for land grabbing by those who are more powerful, better informed, and who have better access to officials as well as greater financial means (Feder and Nishio 1999). Jacobs states that “land titling is most likely to occur where land is becoming a scarce resource and where it attracts commercial interest, either from corporations or from the state and/or national elites” (Jacobs 2017, p. 325). Foreign land acquisitions have gained attention, but “many if not most of these acquisitions are by local actors, often linked with the state. This includes corporations, local elites and government agencies” (Park 2015 in Jacobs 2017). While Agarwal (1994, 2003a) initiated the debate on gender and land rights on the assumption that land titling would bring power, benefits, and well-being to rural women and thus more productivity to their fields, in the end, we argue that what will irreversibly harm women’s rural lives and balanced ecologies is the burgeoning abuse of just such titling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.N.; methodology, C.N. and L.S.; formal analysis, C.N.; writing—original draft preparation, C.N. and L.S.; writing—review and editing, C.N.; visualization, C.N.; supervision, C.N.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the Department of Cultural Anthropology and Development Studies, Radboud university, The Netherlands.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the ethics committee of the research institute Radboud Social Cultural Research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are stored in accordance with the data management protocol of Radboud Social Cultural Research and available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Swelsen completed her bachelor’s degree at Radboud University in Nijmegen. |

| 2 | For the sake of the argument in this paper, we focus on this point that Agarwal persistently brings to the fore. However, her analysis has multiple dimensions, including addressing factors at the macro level that constrain women when it comes to exercising their legal claims, such as legal pluralism and male dominance in administrative and judicial public services. Generally, to date, feminist scholars in the land rights debate still follow Agarwal’s (1994) main argument that patriarchal values and practices supported by customary law prevent women from claiming their inheritance. |

| 3 | Our intention is not to present this as a sharp duality but to distinguish the information we received in arranged interview settings from the insights we gained from participating in women’s ritual activities. Women’s songs, stories, poetry, and prayers are still part of women’s rituals to celebrate mother soil. These verbal expressions show there is a continuum rather than a rupture between (speech) language and (ritual) action. That said, they mostly praise, discuss, or comment on human kinship rather than the more-than-human kinship we focus on in this section (for women’s songs accompanying the rituals, see Notermans (2019)). |

| 4 | This ritual is done during the festival of Dasha Mata, another goddess symbolizing feminine power and fertility, and equally associated with mother soil and Lakshmi. |

References

- Agarwal, Bina. 1994. A Field of One’s Own: Gender and Land Rights in South Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, Bina. 2003a. Gender and land rights revisited: Exploring new prospects via the state, family and market. Journal of Agrarian Change 3: 184–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, Bina. 2003b. Women’s land rights and the trap of neo-conservatism: A response to Jackson. Journal of Agrarian Change 3: 571–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, Bina. 2005. Landmark step to gender equality. The Hindu. Available online: http://binaagarwal.com/popular%20writings/Landmark%20Step%20to%20Gender%20Equality%20TheHindu_25sep05.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Bates, Karine. 2004. The Hindu Succession Act: One law, plural identities. The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 50: 119–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berry, Kim. 2011. Disowning dependence: Single women’s collective struggle for independence and land rights in northwestern India. Feminist Review 98: 136–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird-David, Nurit. 2018. Persons or Relatives? Animistic Scales of Practice and Imagination. In Rethinking Relations and Animism: Personhood and Materiality. Edited by Miguel Astor-Aguilera and Graham Harvey. London: Routledge, pp. 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Carsten, Janet. 2004. After Kinship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chandran, Rina. 2016. Forced by Tradition to Give Up Inheritance, Indian Women Embrace Property Ownership. Reuters. Available online: www.reuters.com/article/india-landrights-women-idINKBN12X1QK (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Chowdhry, Prem, ed. 2017. Understanding Women’s Land Rights: Gender Discrimination in OWNERSHIP. Land Reforms in India: Volume 13. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- 2013. Women’s Right to Inherit Land in India. Devex. Available online: www.devex.com/news/sponsored/women-s-right-to-inherit-land-in-india-81203 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Emerson, Robert, Rachel Fretz, and Linda Shaw. 1995. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago: university of Chigaco Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feder, Gershon, and Akihiko Nishio. 1999. The benefits of land registration and titling: Economic and social perspectives. Land Use Policy 15: 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, Timothy. 1997. A critique of “religion” as a cross-cultural category. Method &Theory in the Study of Religion 9: 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- George, Rachel. 2013. Women Are Being Denied the Right to Inherit Land in India. Mic. Available online: www.mic.com/articles/51687/women-are-being-denied-the-right-to-inherit-land-in-india (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Glaser, Barney, and Anselm Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Mill Valley: Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Govindrajan, Radhika. 2018. Animal Intimacies: Interspecies Relatedness in India’s Central Himalayas. Chicago: The University of Chigaco Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Akhil. 2000. Postcolonial Developments: Agriculture in the Making of Modern India. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna. 2003. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Cecile. 2003. Gender analysis of land: Beyond land rights for women? Journal of Agrarian Change 3: 453–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Mark, ed. 2018. Coloniality, Ontology and the Question of the Posthuman. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Susie. 2017. Beneficial for women? Global trends in gender, land and titling. In Gender and Rural Globalization: International Perspectives on Gender and Rural Development. Edited by Bettina Bock and Sally Shortall. Wallingford: CABI, pp. 322–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, Julia. 2021. Between gender and kinship: Mediating rights and relations in North Indian NGOs. American Anthropologist 123: 330–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, Kanchan. 2017. Persisting inequalities: Gender and land rights in Rajasthan. In Understanding Women’s Land Rights: Gender Discrimination in Ownership. Land Reforms in India: Volume 13. Edited by Prem Chowdhry. Los Angeles: Sage, pp. 296–324. [Google Scholar]

- Merchant, Carolyn. 2020. The Anthropocene and the Humanities: Form Climate Change to a New Age of Sustainablility. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Henrietta. 1994. A Passion for Difference: Essays in Anthropology and Gender. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Jason. 2016. Anthropocene or Capitalocene?: Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism. Oakland: PM Press. [Google Scholar]

- National Portal of India. 2021. Available online: www.india.gov.in/topics/agriculture (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- Notermans, Catrien. 2019. Prayers of cow dung: Women sculpturing fertile environments in rural Rajasthan (India). Religions 10: 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Reilly, Andrea. 2019. Matricentric feminism: A feminism for mothers. Journal of the Motherhood Initiative 10: 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Palriwala, Rajni. 1996. Negotiating patriliny: Intrahousehold consumption and authority in Northwest India. In Shifting Circles of Support: Contextualizing Gender and Kinship in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Edited by Rajni Palriwala and Carla Risseeuw. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, pp. 190–220. [Google Scholar]

- Pattnaik, Itishree, Kuntala Lahiri-Dutt, Stewart Lockie, and Bill Pritchard. 2018. The feminization of agriculture or the feminization of agrarian distress? Tracking the trajectory of women in agriculture in India. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 23: 138–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Nitya. 2005a. Questioning women’s solidarity: The case of land rights, Santal Parganas, Jharkhand, India. The Journal of Development Studies 41: 353–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Nitya. 2005b. Kinship matters: Women’s land claims in the Santal Parganas, Jharkand. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 11: 725–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Nitya. 2017. “Good Women Do Not Inherit Land”: Politics of Land and Gender in India. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ribot, Jesse, and Nancy Lee Peluso. 2003. A theory of access. Rural Sociology 68: 153–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Deborah Bird. 1999. Indigenous ecologies and an ethic of connection. In Global Ethics and Environment. Edited by Nicholas Low. London: Routledge, pp. 175–87. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Ursula. 1980. Women, Work, and Property in North-West India. London: Tavistock Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Shiva, Vandana. 2016. Staying Alive: Women, Ecology, and Development. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Spradley, James. 1980. Participant Observation. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, Nisha. 2011. Feminisation of agriculture: What do survey data tell us? Journal of Rural Development 30: 341–59. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer, Martin. 2008. Contemporary Western Ethnography and the Definition of Religion. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).