Abstract

This paper is about Catholicism in the Philippines, highlighting the events and objects of the popular devotion to the Black Christ Nazarene of Manila, popularly known as Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno of Quiapo or NPJN. What are the motivations of the devotees? How have the religious practices changed over time in Quiapo? This study also calls for more scholarly attention to the historical and religious connection between the Philippines and Mexico, so that through them we can better understand how Filipinos reimagined Baroque Catholicism. In addition to commercial goods, the Manila Galleon facilitated the first transpacific people-to-people exchange along with their ideas, and the transmission and transplantation of Catholicism to the Philippines. This study is both historical and ethnographic, using sources from the archives and research materials collected in the Philippines, Mexico, and Spain. Although the devotion to NPJN is central to the arguments of this paper, the discussion takes a broader consideration of Quiapo, a district of Manila as a shared space for performing the sacred vow or PSV, popularly known as panata. This analytical step is consistent with the main argument of this study, that consideration of the PSV particular to Jesus Christ is crucial to understanding the historical and religious connections and how popular Catholicism has changed in the Philippines.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted the Catholic Church in the Philippines in different ways. The drastic changes can be seen in the temporary closure of churches and the cancellation of daily masses and other religious activities. The pandemic has led Manila’s Quiapo Church to conduct virtual and limited religious gatherings. Quiapo is known in the whole country as the Minor Basilica of Black Nazarene and the most popular ritual site to honor the image of Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno or NPJN. While live-streaming of masses every Sunday is not new to Quiapo Church, the daily fully-online masses were implemented when the lockdown, known locally as Community Quarantine, was announced in the third week of March 2020. When the government imposed a modified lockdown, Quiapo Church was allowed to hold activities with limited capacity while continuing the live broadcast of the daily masses.

In 2021, Quiapo Church decided to suspend the Traslacion1 or the annual procession of Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno. All other fiesta activities were also canceled, and instead of the procession, hourly masses were held on 9 January, the feast day of NPJN. In lieu of the ritual practice of pahalik2 or kissing of the image of NPJN, the church held pagtanaw or viewing of the image. During the pagtanaw, the replica image of NPJN was temporarily transferred to the balcony of the church fronting Plaza Miranda. In Quiapo, the presence of sacred objects like pictures or replicas, particularly of NPJN, is an important aspect of the devotee’s panata or sacred vow. The image of NPJN is crucial to understanding the religious devotion and motivation of the devotees. It represents their desire to perform their panata, either physical or virtual. The power eminent from the image is believed by many devotees to bring happiness and miracles.

The implementation of social distancing measures prohibited devotees from visiting the church. Quiapo devotees marked the 2021 feast day of NPJN with limited capacity inside the church. The Manila police force also controlled the movement of people in the vicinity of the church. The limited capacity was similar to a self-contained group of people or pods for gathering. The self-contained Catholic mass in Quiapo aimed to follow the government rules on social distancing. The limited capacity for religious gatherings suspended the devotees’ regular ritual practices, particularly the performing sacred vow or PSV in Quiapo. Yet, the online experiences of the devotees, especially watching the live broadcast of the mass, were indeed a substitute for visiting a sacred site during the lockdown. Yet, for many devotees, performing their devotion, especially their PSV is what matters to them. It can be personal or inherited, online or physical, but either way, it is of utmost importance to both the young and older devotees. Whether their petitions, prayers, or wishes are granted, or otherwise, a large number of them consider the PSV as something to be fulfilled.

Before the March 2020 lockdown, the 9 January 2020 Traslacion was held and considered the most orderly procession in Quiapo. The three-kilometer procession lasted 16 h. It was the earliest in the last 12 years since the Traslacion was introduced in 2007. Beyond it, the 2015 procession, with approximately five million devotees3, is still considered the longest religious procession in the history of the Catholic Church in the Philippines, lasting for 21 h. Unfortunately, two casualties were reported in the 2015 Traslacion, one member of Hijos del Nazareno who died of cardiac arrest while escorting the image of NPJN, and another fatality was a female devotee who was pinned under the massive crowd. The Traslacion of NPJN of Quiapo is an event re-enacting the historical “transfer” of the image from Bagunbayan, an area near to the present-day Luneta Park and Intramuros, or the old Walled City of Manila, to Quiapo Church in 1767 (Abriol 1976, p. 2). During the procession, many devotees want to touch the image of NPJN or pull the two 50-m-long ropes of the image’s carriage known as andas. For many devotees, joining the procession is an act of faith and a way to perform their panata. Yet, for the Quiapo-based Catholic brotherhood of Hijos del Nazareno or HDN, protecting the image of NPJN from danger is an act they need to perform for spiritual blessings. It is also an act required to earn the highest praise and acceptance of the brotherhood.

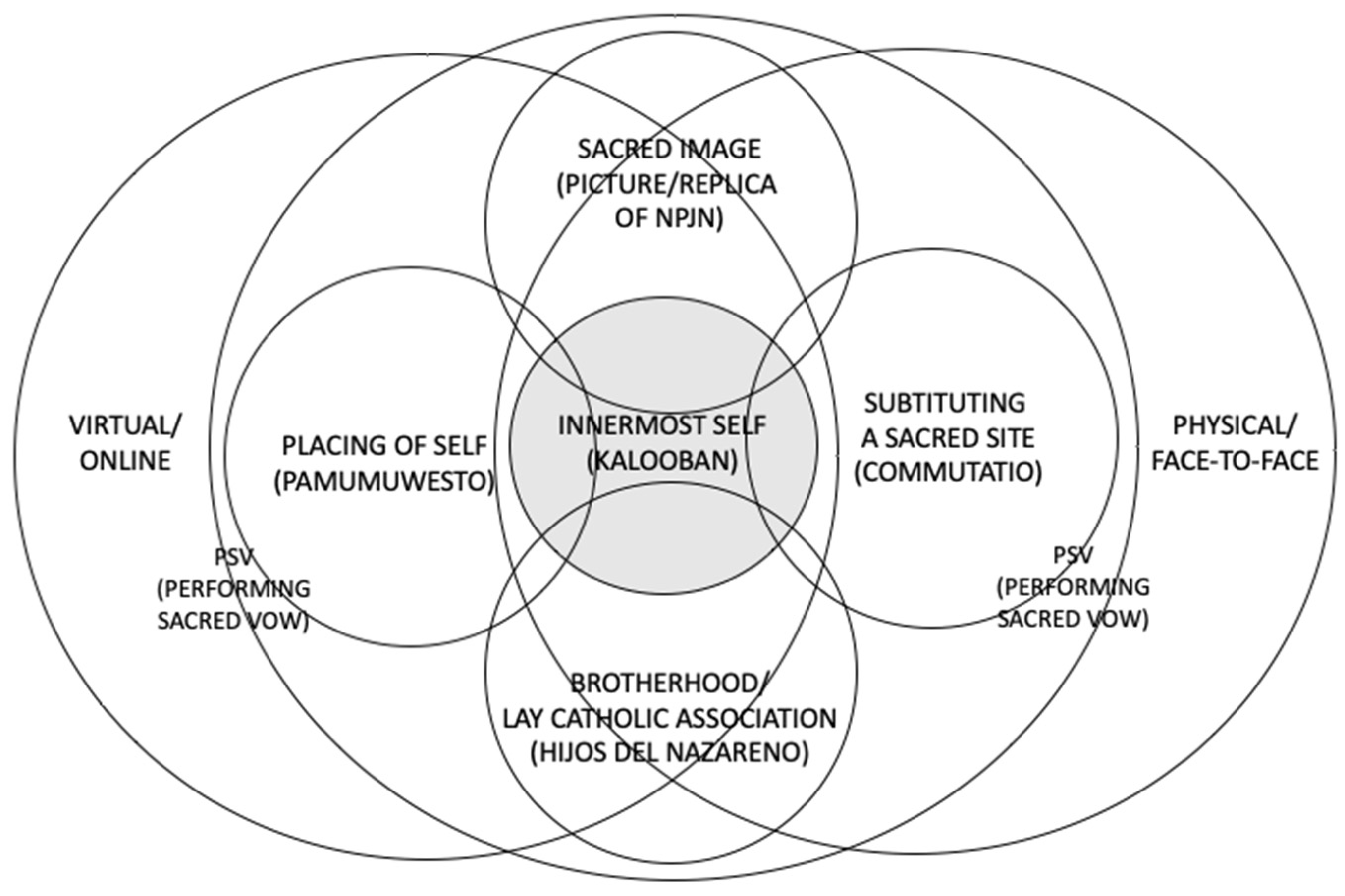

Though how devotees are performing their religious practices is important in this study, the focus is not on performance. The discussion focuses instead on the theoretical understanding of place and space in the study of religion. The main argument is that the COVID-19 pandemic increased the opportunities for alternative forms of performing the sacred vow or PSV to NPJN. This is consistent with the conceptual presupposition that during their PSV, a consideration of the devotee’s placing of self or pamumuwesto, and substituting a sacred site or commutatio, are crucial to understanding their kalooban or innermost selfhood, along with how Catholicism has changed in Quiapo.

2. Methodology and Methods

This study is ethnohistorical, focusing on how contemporary interview data can be used in connection with global historical processes. The discussion and analysis utilized sources from the archives and fieldwork materials collected in the Philippines from 2013 to 2015, 2017 to 2018, and 2019 to 2021. A hybrid approach was also taken, combining face-to-face and online research techniques, with ethnographic data-gathering. A caveat is that the data gathered virtually in this study were from selected online communities in Quiapo, though it does not mean to say that what applies to these communities is also the same for other places in the Philippines. There could be strong similarities but also differences. Ethnography or digital ethnography is suitable for conducting research virtually as it enables the observation of the devotee’s social and religious activities on the Internet and through other technologically-mediated communications (Kozinets 2010, pp. 1–3). The first phase of the research was conducted face-to-face in Manila between mid-2013 and early 2018. The second phase of the research combined face-to-face and online data-gathering due to the COVID-19 lockdown in the Philippines. The interviews were carried out through Zoom, Facebook messenger, Google Meet, and email correspondence between October 2020 to January 2021.

In writing the history of the Traslacion, the challenge was integrating the materials. The historical data focus on three main sources: (1) the Recoletos mission accounts; (2) materials from the archdiocesan archives of Manila; (3) published books and fiesta souvenir booklets, including media kits given to reporters and media editors. The structured and semi-structured interviews were conducted between 2013 and 2019 face-to-face and then between 2020 and 2021 online. All respondents were selected based on the following criteria: (1) devotees and HDN members; (2) Quiapo priests; (3) all aged 18 years and above; (4) willing to participate in the study. Personal communication with the devotees before and during the lockdown, and the insights of the people involved in the online communities and online platforms of Quiapo Church, were used to build the discussion presented here.

3. Space, Objects, and Events in Performing the Sacred Vow in Quiapo: Framing Catholicism in the Philippines

Most contemporary Southeast Asian and Latin American studies, particularly those on Philippine-Mexican relations, have concentrated on economic expansion, political relationships, and security architecture. The knowledge that Filipinos have about Mexico is based on popular culture that is hugely popular among a wide cross-section of society. It is almost that the religious and historical connection of the Philippines with Mexico has become erased from the Filipinos’ memory and only resurfaces in very limited and superficial ways.

The presence of a sacred object, particularly the image of NPJN, is an important aspect of the PSV in Quiapo. Moreover, the space occupied by the sacred image, and temporary space occupied by the devotees during their PSV, play an indispensable role in the ritual process. This study considers the works of Vineeta Sinha (2016) on how ‘spaces devoid of sacrality’ are ‘filled’ with religious symbolism and value (Sinha 2016, pp. 467–88). Objects like replicas or pictures of NPJN that are situated within the sacred site or within the vicinity are perceived to embody intrinsic sacred properties. Sinha noted that sometimes, through simply being placed on the altar in proximity to other sacred items, and within the confines of the shrines, these objects or items also come to embody sacred properties (Sinha 2016, p. 482). Furthermore, spaces are ‘made’ sacred not just for home altars or shrines but also ‘profane’ sites that function temporarily where religiosity is implanted (Sinha 2016, p. 485). In Quiapo, devotees want to bring home not just their own stories about the Traslacion but also physical objects like handkerchiefs, towels, and other religious items that have touched the image or been blessed by holy water. According to Deirdre De La Cruz (2015), objects from sacred sites, either blessed or not, are proof of a most material sort, and the blessings received by the objects can be shared or transferred to anyone (De La Cruz 2015, p. 151). Sacred objects, for Julius Bautista (2010), portray a kind of transportability of spiritual energy inherent in religious material culture (Bautista 2010, p. 38). In Quiapo, whether for religious purpose or secular activities, without a space to produce and shape, as noted by Kim Knott (2005, 2010), ideas and beliefs will remain ephemeral, ungrounded, and unorganized without a space (Knott 2008, p. 1110). This study also considers Kim Knott’s argument on how religion can be located in places, communities, and objects (Knott 2005, pp. 153–84; 2010, pp. 29–43). Quiapo, as a constituted space for the PSV, is full of symbolism, expression, and solidarity. In this study, the impacts of place and space, as theoretical tools for studying Catholicism in Quiapo, were crucial to the analysis and discussion of the roles of pamumuwesto (or placing of self) and commutatio (or substituting a sacred site) in the PSV, to understand the devotee’s kalooban or innermost selfhood. In Quiapo, devotees use the symbolism of their kalooban to make sense of their panata or PSV to honor NPJN (see Scheme 1). The symbolism and expression of pamumuwesto and commutatio in the PSV are an important frame of reference in analyzing a shared notion of religious interiority.

Scheme 1.

Performing the sacred vow (PSV) in Quiapo. (Conceptual Tool of Pamumuwesto and Commutatio).

Although the Spanish maritime trade across the Pacific Ocean was essentially commercial in function, this trading system, known as the Manila Galleon from 1565 to 1815, also served as an apparatus for communication and transportation. The Manila Galleon transported a European space to the Philippines. Through this, Catholicism, particularly the Tridentine Catholic practices, was transplanted to the Philippines. The implementation of the Tridentine policies was a period in which the ideas of devotion, sanctity, holy, and sacred took a new form and resulted in a complex network of religious ideas that influenced many Catholics for a long period. The Tridentine ideas of devotion lay out the conditions for understanding Catholicism in the context of the Spanish colonial period in the Philippines, and the elements of Tridentine Catholicism also known as Baroque were influential to the devotional practices of the devotees in Quiapo. Tridentine Catholicism is the result of the Council of Trent held from 1545 to 1563. While the Tridentine policies were originally directed toward the Counter-Reformation in Europe, this period also resulted in the rise of Baroque Catholicism. In Latin America and other colonial territories, Baroque Catholicism became a controlling instrument in knowledge production and the production of space. In the Philippines, Baroque became a source of symbols for ritual expressions, which are distinctive in showing the devotee’s innermost selfhood. The partaking of the body and blood of Christ, for example, resonates in the ritual feasting and the Tagalog translations of the texts spoken by the priest during consecration. The symbolism of the consecration becomes a source of the notions of sanctity, strength, power, and potency (Andaya 1994, pp. 531–34). According to Vincent Rafael (1988), the idea of religious transformation emerged through the Filipino reinterpretation of symbols and signs, especially in their Catholic ritual practices (Rafael 1988). The historical dimension of this study argues that Baroque Catholicism reached the Philippines through the Manila-Acapulco Galleon trade, the influences of which can be seen in the reinterpreted ritual and devotional practices in Quiapo. While most of the recent studies on Catholic devotions in the Philippines have focused on the apparitions of Mary, images of the Crucified Christ have also been studied and explored, but have received little attention in terms of their distinctiveness as an original image with devotional significance, even within the larger category of miraculous crucifixes and life-size images of Christ. In this study, the interpretation of the religious images in the Philippines, particularly the image of NPJN, is given a potential indigenous or local meaning and symbolism to make sense of how and why devotees perform their panata.

4. Analysis and Discussion

This study used two layers of investigation: (1) the role of Quiapo Church in the history of Catholicism in the Philippines; (2) the devotees’ engagement with space when performing the sacred vow or PSV and the use of the Internet in their practices. These two layers of analysis and discussion helped with describing and interpreting how the situated body of the devotees makes sense of their ritual practices and experiences revealed by pamumuwesto and commutatio. The location of the self in the ritual practice to honor NPJN is called pamumuwesto. As the PSV, pamumuwesto is how devotees position themselves in a ritual space; the most common pamumuwesto happens inside the church and during the procession. Then, as another aspect of the PSV, commutatio, on the other hand, is how devotees are substituting or exchanging a sacred site, with a stand-in for the actual site. In this way, devotees who could not go to the church because of the lockdown or for whatever reason could fulfill their religious practices at home or online and receive the same blessings. A substitute ritual site can also be a space near or outside the church, or along the road during the procession.

The reasons why the discussion on the historical and religious linkages between the Philippines and Mexico are important to this study are as follows: (1) in addition to commercial goods, the Manila-Acapulco Galleon trade facilitated people-to-people exchange, communicating their ideas and aspects of religious life. Although geographically closed to Southeast Asia, the Philippines was closely connected to Mexico when Spain ruled the country from 1565 to 1898. (2) Both in the Philippines and Mexico, Catholicism is the predominant religion, sharing similarities and challenges, especially for the process of integrating pre-Spanish religious understanding with that of Iberian Catholic practices.

While there are distinct ritual practices throughout Central and South America, the history of Mexico and Latin American Catholicism is not complete without mentioning the story of the Black Virgin Mary of Guadalupe. Images of Christ are also popular, like the Black Christ of Mexico City, the Black Christ Nazarene of Panama, and Christ Corcovado of Rio de Janeiro. Perhaps the most popular image of Christ is the Black Christ of Equipulas, which is central to the history of Catholicism in Guatemala and also in countries like El Salvador, Honduras, and Belize. Though discussion on the image and devotion to Christ is central to this study, this discussion does not claim that the history of NPJN is directly connected to those places in Central and South America, though they do share similarities and religious connections. Instead, the growth, history, and development of mission churches in Mexico are crucial to the history of Catholicism in the Philippines. Manila was formerly a mission territory or part of the diocese of Mexico.

4.1. The Transmission of Catholicism to the Philippines

In this study, the emphasis given to the Manila Galleon focuses on its role in the transmission and transplantation of Catholicism to the Philippines. It examines how missionaries, particularly the Order of Augustinian Recollects or Agustinos Recoletos, were able to access the Philippines, and assesses the methods they used to expand their missionary activities beyond the Americas. Mexico became an important source of administrative manpower and the financial center for both the royal government and various religious orders (Schurz 1939; Phelan 1959; Bernal 1965; Clossey 2008). Mexico City also served as an ecclesiastical and religious hub for missionaries destined to travel to Asia and other parts of the Americas, as missionaries bound for those areas often had to pass through Mexico. Many of the missionaries who traveled to Mexico had, in fact, intended to use Mexico City and Acapulco to reach the Philippines (Bernal 1965; Fernandez 1979; Clossey 2008). In the Philippines, the policy of resettling the local population followed the Mexican or South American pattern where a plaza and a church at the center is the typical urban masterplan. The early missionaries had long since found that the most effective way of spreading Catholicism is converting the local leaders and their family (Andaya 1994, pp. 531–32). In many places in the Philippines, the different religious orders established schools, usually very close to the church, to instruct the young about the Catholic teachings.

If the Tridentine period was the response of the Catholic Church to changing historical circumstances, it also resulted in the rise of Baroque Catholicism. Baroque is synonymous with a more intense devotional practice. To formalize the council’s decrees, also known as the Tridentine policies, dioceses in the Americas convened their own local councils. Lima’s episcopal councils was held in 1551–1552, 1567–1568, 1581–1583; Mexico in 1555, 1565, 1585; and Ecuador in 1570, 1594, 1596 (Bulman and Parrella 2006, p. 44). Across the Pacific, the Philippines was previously a suffragan territory of the Archdiocese of Mexico until 1595, when Manila was elevated to an archdiocese. However, Manila did not hold its own council; therefore. the “Acts of the Third Council of Mexico of 1585” were implemented over the following centuries in the country (Fernandez 1979, p. 95). The decrees of 1585 resulted in the rise of reinterpreted Baroque devotional practices in the Philippines.

The works of Joseph De la Conception, particularly his Relacion provincia de San Nicolas de Tolentino de las Islas Philipinas (De la Conception 1751), and Juan De la Concepcion’s Historia de Filipinas (De la Concepcion 1788), are two of the most important sources used in connection with the role of the Recoletos in the history of the Quiapo and NPJN. The works of De la Concepcion were specifically cited in the works of Vicente Catapang on the Brief History of the Church of Quiapo and Its Miraculous Image Jesus Nazarene (Catapang 1937). In July 1605, 14 Recoletos boarded a ship in Cadiz, Spain sailing to Mexico. They boarded the galleon Espiritu Santo from the port of Acapulco crossing the Pacific Ocean, though only 13 missionaries reached the Philippines in 1606. They landed first in Cebu on 12 May and reached the shores of Manila on 31 May, the Recoletos brought with them a life-size image of Christ Carrying the Cross from Mexico that became known as the Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno, or NPJN of Quiapo (De la Conception 1751; Catapang 1937; Romanillos 2004). Most of the Christo-centric devotions that were introduced to the Philippines and Mexico were closely related to European practices, particularly during the Baroque period, but the devotional practices can be traced as far back as medieval times (Bulman and Parrella 2006). The Christo-centric devotions became very popular during the late 16th and early 17th centuries following the decrees of the Council of Trent on the liturgy of the Eucharist, the commemoration of Christ’s Passion during Holy Week, and the veneration of the images of the saints (Tanner 1990; Bulman and Parrella 2006, p. 44). In the Baroque Catholic tradition, all religious images, particularly of Christ and Mary, had to exemplify the aesthetic ideal of perfection. The more “lifelike” and “beautiful” the images appeared, the more perfectly the images could inspire the devotion and religious imagination of the devotees. The widespread use of religious images served not only as an aid to prayer but also became an important aspect of a more performative form of religious practices. Moreover, the production of hagiographies, sermons, prayer books, and spiritual manuals during the expanding print culture had a layout that transformed the different religious devotions (De La Cruz 2015, p. 27). In the Philippines, the popular devotions to Christ became sources of ritual expressions that can still be seen in contemporary places and spaces of religious practices.

4.2. Quiapo Church in the History of Catholicism in the Philippines

In 1574, the first church of Quiapo was dedicated to the Holy Name of Jesus. The first church was destroyed during the Chinese invasion of Manila on 29 November 15744; this episode also saw the burning of numerous other churches and houses in Manila. Before it was established as an independent parish on 29 August 1586, Quiapo was previously under the parish jurisdiction from 1574–1578 of Santa Ana de Sapa; the present-day Santa Ana is a district of Manila located south of the Pasig River (Abriol 1976). It was Governor-General Santiago de Vera who signed the order to establish Quiapo as a new parish, and the patron saint was also changed to St. John the Baptist. Quiapo has celebrated the feast day of St. John the Baptist every 24 June since 1586. When the image of NPJN was transferred to the church in 1767, the images became co-patron saints. Quiapo celebrates the feast day of NPJN every 9 January. Since 1767, the church has held an annual NPJN procession in the streets of Quiapo. In 2007, the church introduced the Traslacion, a procession re-enacting the official transfer of the image of NPJN from Luneta and Intramuros to Quiapo.

The 2021 procession of Quiapo, or the Traslacion of Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno, was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The decision was confirmed by the Quiapo Church management and the city government of Manila. Instead of a procession, Quiapo Church held masses both online and physically with limited capacity inside the church. The traditional pahalik or kissing of the image was also canceled, but pagtanaw or viewing of the image was held at the balcony of the church fronting the historical Plaza Miranda. The year before the COVID-19 pandemic, the procession of NPJN in 2020 lasted for 16 h and was the earliest in the last 12 years since the “re-enactment of the transfer of the image” was introduced in 2007 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Traslacion in numbers5.

The history of the 9 January procession of Quiapo can be traced back to the official transfer of the image from the Church of San Juan de Bautista in Bagumbayan, an area near present-day Manila’s Luneta Park to the Church of San Nicolas de Tolentino in Intramuros and then to Quiapo Church (Catapang 1937, pp. 2–3). The origin of the image was attributed to a Mexican-Nahuatl wood-carver who was commissioned by the Recoletos to create a life-sized image of Christ. In 1606, the image arrived in the Philippines via the Manila Galleon from the port of Acapulco in Mexico. The Recoletos is the original owner and caretaker of the image that later became popularly known as NPJN. According to tradition, the life-sized statue was originally of fair skin color, just like the images of Christ commonly found in Europe.

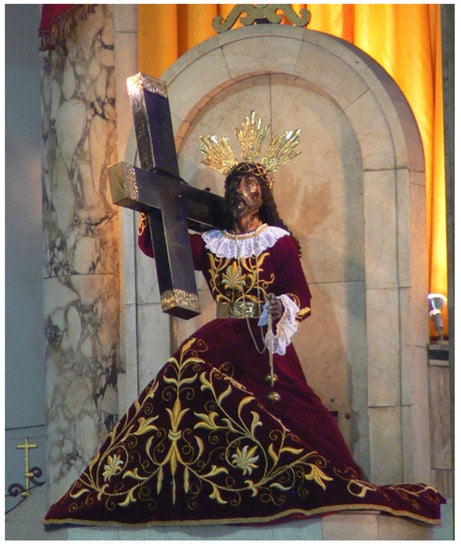

Quiapo is one of 16 districts of Manila with a total land area of 85 hectares. Much of the Quiapo area remains residential in nature, with families occupying the second floors of post-WWII houses while the ground floors are rented out for commercial use. For many devotees, Quiapo Church has countless stories of rising from the ruins because of the fires in the years 1603, 1791, and 1929; the Sangleys or Chinese uprising of 1606; the earthquakes of 1645 and 1868; temporary cancellation of religious activities due to the pandemics of 1820, 1882, 1902, 1918, and 2020–2021. The church was demolished and rebuilt in 1863, and again damaged but not totally destroyed during the WWII bombings of 1945. These stories, according to many devotees, are more than historical facts but also miracles later attributed to the miraculous doings of NPJN. Quiapo Church was burned or partially destroyed, but the image remained intact. NPJN is a life-sized image of Christ wearing a maroon robe, embroidered in gold and silver, with a crown of thorns and a diadem that forms three silver rays on the head (see Figure 1). The image’s right shoulder rests on a wooden cross similar to pasan, re-enacting a biblical scene of Christ’s struggle to stand up after a fall, with a face manifesting pain and suffering. The complexion is black with real human hair. The image resembles more of an indigenous-looking person. For many devotees, the image of NPJN is a “visual representation” and a “metaphor” of struggling to stand up after a fall because of a problem.

Figure 1.

Image of the Black Christ Nazarene of Quiapo, Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno or NPJN (photograph by the author).

The devotion to NPJN was introduced by the Recoletos. They co-founded the Intramuros-based Cofradia Señor Jesus de Nazareno or the Confraternity of Our Lord Jesus of Nazareth on 20 April 1621. A Quiapo-based brotherhood or confraternity was founded in the 1930s that later became known as the Hijos del Nazareno. The exact date when the image was transferred to Quiapo Church is still debatable. It is very likely that a replica was made to substitute the image enshrined in Intramuros, which existed until it was destroyed during WWII. Filipino historians argue that the original 16th-century image was the one transferred to Quiapo. According to Vicente Catapang (1937), before the second burning of Quiapo Church on 15 January 1791, the image was transferred (Catapang 1937, p. 3). Yet, it is generally assumed that the image was moved to Quiapo a few years before said date, most probably in 1767. The image was transferred to Quiapo Church following the order of Basilio Sancho de Santa Justa. Sancho de Santa Justa was a Manila archbishop from 14 April 1766 to 15 December 1787 so it is also safe to assume that the transfer was probably between 1767 and 1787 (Catapang 1937, pp. 3–4). Sancho de Santa Justa was replaced by Juan Antonio Orbigo de Gallego on 15 December 1788. Gallego was the archbishop of Manila until 17 May 1797.

In 1933, the Archdiocese of Manila commissioned Filipino architect Juan Nakpil to design and supervise the construction of the church. In Nakpil’s design, a dome was constructed and a second bell tower was added following the original Mexican Baroque-style facade. The newly constructed church survived the 1945 WWII bombings. Juan Nakpil was commissioned again in 1984 to remodel the interior of the church to accommodate the growing number of devotees. Nakpil designed an expanded interior but kept the original Baroque-style facade and the original main altar. The church expansion project was blessed by Manila Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin, together with the Apostolic Nuncio to the Philippines, Bruno Torpigliani, on 28 September 1987. Pope John Paul II declared Quiapo Church a minor basilica of the Catholic Church on 11 December of the same year and it was consecrated on 1 February 1988, officially named the Minor Basilica of the Black Nazarene. In 1988, Quiapo Church commissioned Santero Gener Malaqui, a popular Filipino sculptor, to create an exact replica of the image; the aim of the replica project was to protect the original image from accident or damage. Since 1998, only the body of the original with the replica head has been brought out for processions, while the original head in a replica body is the one enshrined permanently at the main altar. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, four processions were held in Quiapo: (1) morning of 31 December (Thanksgiving procession); (2) procession of the replicas; (3) 9 January feast day or Traslacion; (4) every Good Friday during Holy Week.

Before 2007, the traditional 9 January procession was called pasan, a Tagalog word for “carrying”, because originally, the image was placed in a carriage designed to be carried on the shoulders in a procession through the streets of Quiapo. In 2009, the Tagalog term salya became popular. The word is from pag-salya, which means “to pull”; the current carriage or andas is now wheeled and pulled by a pair of 50-m ropes. For many devotees, the rope is a symbolic extension of NPJN’s cross. Although historically correct, the term Traslacion, which means the transferring of the image from Bagumbayan to Quiapo, was only introduced in 2007. That year was the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the image from Mexico to the Philippines. The arrival of the Recoletos with the image in 1606 became the basis for the historical origin of NPJN. Monsignor Jose Clemente Ignacio has popularized the term Traslacion. He was the parish priest and rector of Quiapo Church during the 400-year celebration. When Monsignor Hernando Coronel assumed the rectorship of Quiapo Church in 2015, he continued the Traslacion from Luneta Park to Quiapo and started the live-streaming of masses. The online initiatives of Coronel became more popular during the COVID-19 lockdown. Currently, the virtual presence of Quiapo Church on Facebook has 3.5 million followers. The YouTube channel of the Minor Basilica of the Black Nazarene has more than 220,000 subscribers.

4.3. Performing the Sacred Vow in Quiapo

In Quiapo, performing the sacred vow or PSV means two things. First, it is both physical and virtual; it connects the experience of the devotees in performing their panata by highlighting the interplay of “events” and “objects”. Second, it is used by the devotees and HDN members as a metaphor for “gratitude” and “reciprocity”, or the reciprocal process happening to return the favor or debt of gratitude to NPJN.

In Quiapo, the presence of a sacred object is an important aspect to understanding the religious reality of the devotees. It presupposes that the image of NPJN is the center of their PSV. A female devotee6 talked about the significance of the image’s physical appearance. According to her, “Every time I pray in front of the image of NPJN, the image reminds me of Christ’s pain and suffering just to save us, for our salvation. When I look at the face of Christ while he carried the cross, it reminds me of the heavy load, perhaps very similar to my problems, and the suffering he endured for us, which we also need to endure as a form of trial.” A large number of devotees consider a heavy load or problem as a “trial” or pagsubok that one should wait out and bear; locally, this is known as magtiis from the Tagalog word tiis, which means to suffer or endure. For many devotees, “to endure” means that: (1) it is always the will of NPJN to grant or not grant their wishes; (2) that decision may hinge on their sinfulness, therefore, requiring them to do more PSV; (3) NPJN always wishes them nothing but happiness and success in life.

During the PSV, devotees always have a picture or replica of NPJN that has been blessed by holy water or has touched the image enshrined in the church. The picture or replica is not an ordinary object according to many devotees7, not ephemeral, but a sacred object that they can keep and place in their family or home altar. According to Deirdre de la Cruz, objects from sacred sites are proof of a most material sort, witnessed and possessed not just by one but by many (De La Cruz 2015, p. 151). The blessing received by the objects and by them can also be shared or transferred to the whole family or community. The sacred object, like the images or statues, according to Julius Bautista (2010), depicts a kind of transferable or spiritual energy inherent in religious material culture (Bautista 2010, p. 38). A huge number of devotees somewhat create their own kinds of relics from those they think of as holy and bring them back home to fulfill their spiritual needs. In Quiapo, many of the devotees venerate and seek contact with the image of NPJN because, for them, the sacred image connects the divine and their world. For them8, the sacred can also manifest in the world through their PSV. By performing different bodily and symbolic gestures, they are invoking the sacred. Some of the most common bodily gestures of the devotees are: (1) queuing to touch or punas-punas and to kiss or pahalik the images; (2) praying on their bent knees and practicing self-flagellation and mortification to recall Christ’s sufferings; (3) fasting and abstaining even outside the Lenten season. For many of the devotees, these bodily gestures are a symbolic way of forging a kind of “spiritual union” with NPJN. The simple act of touching and kissing any part of the sacred image is a gesture of respect, just like showing respect to the elders of the family. Furthermore, touching and kissing are also ways for them to be close and connected to the image, having a direct line of talking or communicating with NPJN.

The presence of brotherhood, confraternities, and other forms of Catholic lay association is another important feature of the PSV. They are crucial to the transmission and continuation of devotional practices. Confraternities, also known as brotherhoods, are medieval phenomena that originated from European Catholic communities. Confraternities and brotherhoods became popular in Latin American colonies of Spain including the Philippines. Many of the confraternities in the Philippines have undergone modifications over time. This study focuses on the Quiapo-based brotherhood of Hijos del Nazareno or HDN (see Table 2). HDN membership currently stands at more than 8000 members, not only from Metro Manila but also other provinces nationwide and overseas chapters. Some of the HDNs have created their own Facebook pages to serve as communication platforms for their members and followers. The robust popularity of the devotion to NPJN has also been attributed to the continuous presence and increasing membership of the Hijos del Nazareno.

Table 2.

Quiapo’s Hijos Del Nazareno (HDN).

HDNs are subdivided into balangays or small communities. HDNs have rules to follow, which are typically oral, similar to those of a gentleman’s agreement. HDN is a male-dominated confraternity, but there are plans to create a women’s group in 2022. An HDN applicant is required to make a request either in writing or verbally, stating their intention to a senior member or directly to the president of a balangay. A devotee of NPJN, regardless of age, can apply for membership. It is not standard among the balangays, but a small membership fee may be collected to cover the costs for the identification card, the official shirt, and other expenses incurred during group meetings, pilgrimages, and other such activities. Quiapo Church has been very supportive, providing spiritual direction and organizing activities like retreats and recollections. The church also helps to cover the costs of some of the needs of the different groups, like paying for the official uniforms and providing meals during the preparation stage and actual day of the annual Traslacion. HDN participation is not limited to the 9 January procession. They are also tasked to serve during the mass, and they assist in guiding the pilgrims and devotees wanting to touch the image of NPJN. While the HDN’s charitable activities focus mainly on providing material aid to sick members and organizing communal prayers for the dead, including funeral processions and burials, HDN also provides charity to other pious institutions, especially those under the parish-jurisdiction of Quiapo Church. Beyond this, HDN charitable activities have expanded outside of Quiapo. They are now providing humanitarian aid during crises like typhoons and emergency response during disasters in different parts of the country. HDN, or the Catholic lay association, addresses the importance of lay actors for the growth of the devotion to Christ in the Philippines.

4.4. Pamumuwesto and Commutatio in Quiapo

During the lockdown, Quiapo Church used social media to reach out to their parishioners. It regularly uploaded news and information regarding COVID-19 and the available assistance for those affected by the pandemic. The church reinforced the live-broadcasting of all masses on Facebook and launched a YouTube channel for live-streaming of all religious activities. Although the usual ritual practices of many of the devotees, such as attending mass and Friday devotion, were temporarily suspended. In place of these, engaging in the PSV at home or in a specific space or puwesto proved to be effective. One could not touch the sacred image physically but through a screen instead, and according to many devotees9, they could catch a glimpse of NPJN in this way. While online masses and virtual devotion at home are not the same as going to church physically, online streaming of masses and other religious activities supports the continuity of the PSV.

In Quiapo, the PSV generates meaning through the interaction of the physical and virtual spaces. The PSV, as pamumuwesto or placing of the self, is a ritual process that narrates the devotee’s religious experience. The experiences and stories of many devotees are told and shared in different ways, based on: (1) how they are performing their religious practices to honor NPJN; (2) how they are interacting with other devotees; (3) how different historical accounts are incorporated into the formation of the devotee’s sense of space.

In this study, the use of the Tagalog word pamumuwesto or puwesto is similar to the Spanish words puesto and posicion, which mean place and position, respectively. For many Tagalog communities, puwesto is also synonymous with sacred places in nature like mountains, rivers, caves, trees, and even waterfalls, while pamumuwesto is performed according to tradition or puwesto to puwesto (place to place). In Quiapo, placing the self in the physical or virtual space is a ritual act. The practice of pamumuwesto in Quiapo has three important components: (1) God (NPJN) as the source of power and blessings; (2) the devotee or receiver of power or blessings; (3) the space or puwesto, either temporary or permanent.

The PSV as pamumuwesto is how devotees make temporary homes for themselves, others, and NPJN. A replica or picture of NPJN, after being blessed by a priest or holy water, is usually placed or kept at home by devotees, who create a home altar to keep safe the whole family. Many devotees view their home within a larger community, seeing themselves as religious beings dwelling in a place as well as a crossing in space. Through their practice of pamumuwesto, devotees overcome not only the boundaries of the physical space but also join the other devotees, either from the same community or from other places. In the case of online PSV, devotees welcome and interact with their fellow devotees virtually. They, likewise, share the place and space with others, for example, their family, community or group, or the people who guide them to properly express their devotions or religious practices.

Before the pandemic, Quiapo Church was already known for its virtual activities through live-streaming. The two main platforms used by the church are Facebook and YouTube. The majority of the devotees describe an online mass as better than nothing at all. Social distancing and the religious bubble, to some extent, helped with controlling the spread of the virus. The virtual space created an alternative platform for religious activities. According to an HDN member10, “Every time I attend online mass, I always wait for the camera to focus on the image of NPJN. I want to gaze quickly at the image. When I look at the face of Christ on the TV screen, it reminds me of being there inside the church; I can feel that NPJN is looking at me.” Online PSV is directed toward the sacred image. As noted by the devotee, NPJN already looks at them before they bring their eyes to the image. This act of gazing does not manifest in a direct manner, but the message for them is that they are journeying with NPJN. Although the sense of community is lost, viewers re-imagine a community in an actual live-streamed mass. Attending mass is an important part of the devotee’s PSV in Quiapo, especially on Friday and Sunday. A huge number of devotees mentioned that they created a prayer altar with the television, or that any streaming device became a critical component of the prayer space. For selected HDN members11, attending religious activities both physically and online is now part of their PSV in Quiapo. Yet, the majority of devotees and HDN members noted that the Internet cannot replace the experience of receiving the Eucharist and attending certain such religious activities in person. The sad reality also is that those who do not have access to technology, particularly television and the Internet, cannot participate in the online religious activities.

In Quiapo, the PSV is distinctive in showing the devotee’s kalooban or innermost selfhood. The devotee’s sense of self is connected to their sense of Quiapo as a sacred and profane space. The space occupied by the devotee could be the actual site of the PSV or a substitute sacred site. The practice of “visiting a substitute sacred site” is known as commutatio. The idea is for pilgrims or devotees who could not go to Jerusalem for whatever reason to make the pilgrimage to Rome and receive all of the same blessings (Miedema 1998, pp. 76, 81, 86–87, 89). Here, home or the PSV at-home is a substitute for Quiapo. Alternatively, if pilgrims or devotees could not make it to Quiapo, their local community of NPJN devotees could be a substitute. The term commutatio is from a Latin word for exchange or substitution. In Quiapo, the practice of “substituting a sacred site” is part of the “new normal” of religious activities due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In Quiapo, commutatio is both collective and personal. While the virtual PSV has a collective aspect through ritual practice in an imagined community, it is also a personal journey, a way for devotees to construct their own paths for the PSV. Moreover, commutatio is not simply substituting the physical sacred sites but also about the virtual space the devotee is occupying; it is not just about viewing and looking at the screen but also encountering others virtually. It is performative, imagining and transporting the minds of the devotees to the sacred. During the pandemic, it meant “reimagining NPJN” and re-enacting their PSV from the church, bringing it to life at home.

5. Conclusions

In Quiapo, the pandemic, miracle stories and tales of survival, the construction and reconstruction of the church, and episodes of “transferring” and “returning” NPJN may represent some of the most significant events in the growth and development of the devotion to NPJN and how it has changed over time. In Quiapo, performing panata or the PSV, either personal or inherited, occupies a singular importance among the devotees and HDN members. A large number of them view the PSV as an act of returning the favor or utang na loob to NPJN. It is also a form of sacrifice or tiis, whether or not their prayers or petitions are granted; what is important for them is for their PSV is be fulfilled, either as a lifetime commitment or one that can be passed on to the next generation or any member of the extended family. Through pamumuwesto and commutatio, the PSV in Quiapo is unique in showing the devotee’s innermost selfhood. The PSV is about how devotees occupy and share a space. It is symbolic and performative. The interplay of bodily gestures, text, words, and objects is believed to convey the messages of the essential truths of the devotee’s actions. It can intensify joy and religious satisfaction. The PSV increases the joyful feeling of devotees wanting to see or touch the image of NPJN. While it raises issues regarding the relationship between the physical and virtual, the PSV, for many devotees, is an effective ritual practice. However, the efficacy of the online PSV remains moderate for many older devotees who prefer a real-time, physical visit to an actual church.

Funding

The twelve months fieldwork from January 2015 until 31 December 2015 were funded by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, National University of Singapore, as part of my doctoral research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to De La Salle University for permission to reprint portions of my conference paper on Quiapo and Antipolo as Shared Spaces for Performing Panata: An Ethnohistorical Analysis of Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno and Nuestra Señora de la Paz y Buen Viaje. Pamana at Sining: Valuing the Arts. (Proceedings of the 13th DLSU Arts Congress).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See details of 2021 Traslacion cancellation in Tiangco, Minka Klaudia, “No Traslacion 2021 procession amid COVID-19 pandemic,” Manila Bulletin, 23 October 2020. |

| 2 | See details of 2021 Pahalik cancellation in Aquino, Leslie, “‘Pahalik’ for Feast of Black Nazarene in January cancelled,” Manila Bullentin, 25 October 2020. |

| 3 | From various sources and reports from Quiapo Church; Philippine National Police (PNP); City Government of Manila; Hijos Del Nazareno (HDN); Manila Bulletin; Philippine Daily Inquirer; GMA News; ABS-CBN News; CNN Philippines; TV5; PTV; Rappler; Philippine Red Cross; NDRRMC; DOH-HEMS; MDRRC; DPWH-Manila; MMDA. |

| 4 | See the accounts of the 1574 Battle of Manila in Juan Francisco Maura’s La Relacion del suceso de la venida del tirano chino del gobernador Guido de Lavezares 1575. |

| 5 | From various sources: Quiapo Church; LGU of Manila; Philippine National Police; Manila Bulletin; Philippine Daily Inquirer; GMA News; ABS-CBN News; Rappler; Philippine National Red Cross; NDRRMC; DOH-HEMS; MDRRC; MMDA; MPD. * In 2008, Quiapo Church management decided that the procession should start at Quiapo’s Plaza Miranda. In the years 2009 to 2020 the starting point of the procession were held at Luneta Park. |

| 6 | Maria Cruz, a devotee and resident of Laguna Province. Interview and personal Communication. Manila, 9 January 2019. |

| 7 | Luis T., Rio B., Jose S. members of Hijos del Nazareno who are residents of Caloocan. Interview and personal Communication. Manila, 7 January 2018. |

| 8 | Lito C., Rommel T., Gab C., John R., Norman A. devotees and residents of Quiapo district. Interview and personal Communication. Manila, 7 January 2015. |

| 9 | Ten members of Hijos del Nazareno who are residents of Manila. Interview and personal Communication. Manila, 10–11 January 2021. |

| 10 | Lance R., a Hijos del Nazareno member and a resident of Manila. Interview and personal Communication. Manila, 10 January 2021. |

| 11 | Ten HDN members who are residents of Manila. Interview and personal Communication. Manila, 10 January 2021. |

References

Primary Sources

Interview materials and other documents collected in Quiapo: (1) Jose Clemente Ignacio 2014; 2015; (2) Hernando Coronel 2014; 2015; 2016; 2018-mid 2020–2021; (3) Selected devotees in Quiapo, January 2013; January & May 2014; January, April, May 2015; December 2018–2019; January 2020; January 2021.Secondary Sources

- Abriol, Jose. 1976. Aklat ng Mahal na Poong Jesus Nazareno. Manila: Quiapo Church. [Google Scholar]

- Andaya, Barbara. 1994. Religious Developments in Southeast Asia, c. 1500–1800. In Cambridge History of Southeast Asia: From Early Times to c.1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bautista, Julius. 2010. Figuring Catholicism: An Ethnohistory of the Santo Niño de Cebu. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, Rafael. 1965. Mexico en Filipinas, Estudio de Una Transculturacion. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Bulman, Raymond, and Frederick J. Parrella, eds. 2006. From Trent to Vatican II: Historical and Theological Investigations. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Catapang, Vicente. 1937. Brief History of the Church of Quiapo and Its Miraculous Image Jesus Nazarene. Manila: Fajardo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clossey, Luke. 2008. Salvation and Globalization in the Early Jesuit Missions. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De la Concepcion, Juan. 1788. Historia de Filipinas. Manila: Agustin de la Rosa y Balagtas. [Google Scholar]

- De la Conception, Joseph. 1751. Relacion Provincia de San Nicolas de Tolentino de las Islas Philipinas, del Origen, Progressos y Estado de Dicha Provincia, y de los Religiosos que han Trabaxado en ella, Desde el año de 1605 hasta el Presente de 1651. Manila: Convento de San Juan de Tolentino de Manila. [Google Scholar]

- De La Cruz, Deirdre. 2015. Mother Figured: Marian Apparitions & The Making of a Filipino Universal. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, Pablo. 1979. History of the Church in the Philippines, 1521–1898. Manila: National Bookstore. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, Kim. 2005. The Location of Religion: A Spatial Analysis. London and Oakville: Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, Kim. 2008. Spatial Theory and the Study of Religion. Religion Compass 2: 1102–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, Kim. 2010. Religion, Space, and Place: The Spatial Turn in Research on Religion. Religion and Society: Advances in Research 1: 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, Robert. 2010. Netnography: Doing Ethnographic Research Online. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Miedema, Nina. 1998. Following in the Footsteps of Christ: Pilgrimage and Passion Devotion. In The Broken Body: Passion Devotion in Late-Medieval Culture. Edited by Alasdair MacDonald, Bernahard Ridderbos and Rita Schlusemann. Groningen: Egbert Forster, pp. 76–89. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, John Leddy. 1959. The Hispanization of the Philippines: Spanish aims and Filipino Responses, 1565–1700. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rafael, Vicente. 1988. Contracting Colonialism: Translation and Christian Conversion in Tagalog Society under Early Spanish Rule. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Romanillos, Emmanuel Luis A. 2004. Augustinian Recollect Legacy to Arts and Culture. In Recoletos 400: History, Legacy and Culture. Manila: San Sebastian College-Recoletos. [Google Scholar]

- Schurz, William. 1939. The Manila Galleon. New York: E.P. Dutton & Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, Vineeta. 2016. Marking spaces as ‘sacred’: Infusing Singapore’s urban landscape with sacrality. International Sociology 31: 467–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, Norman, ed. 1990. Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils. 2 vols. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).