Children in Need: Evidence for a Children’s Cult from the Roman Temple of Omrit in Northern Israel

Abstract

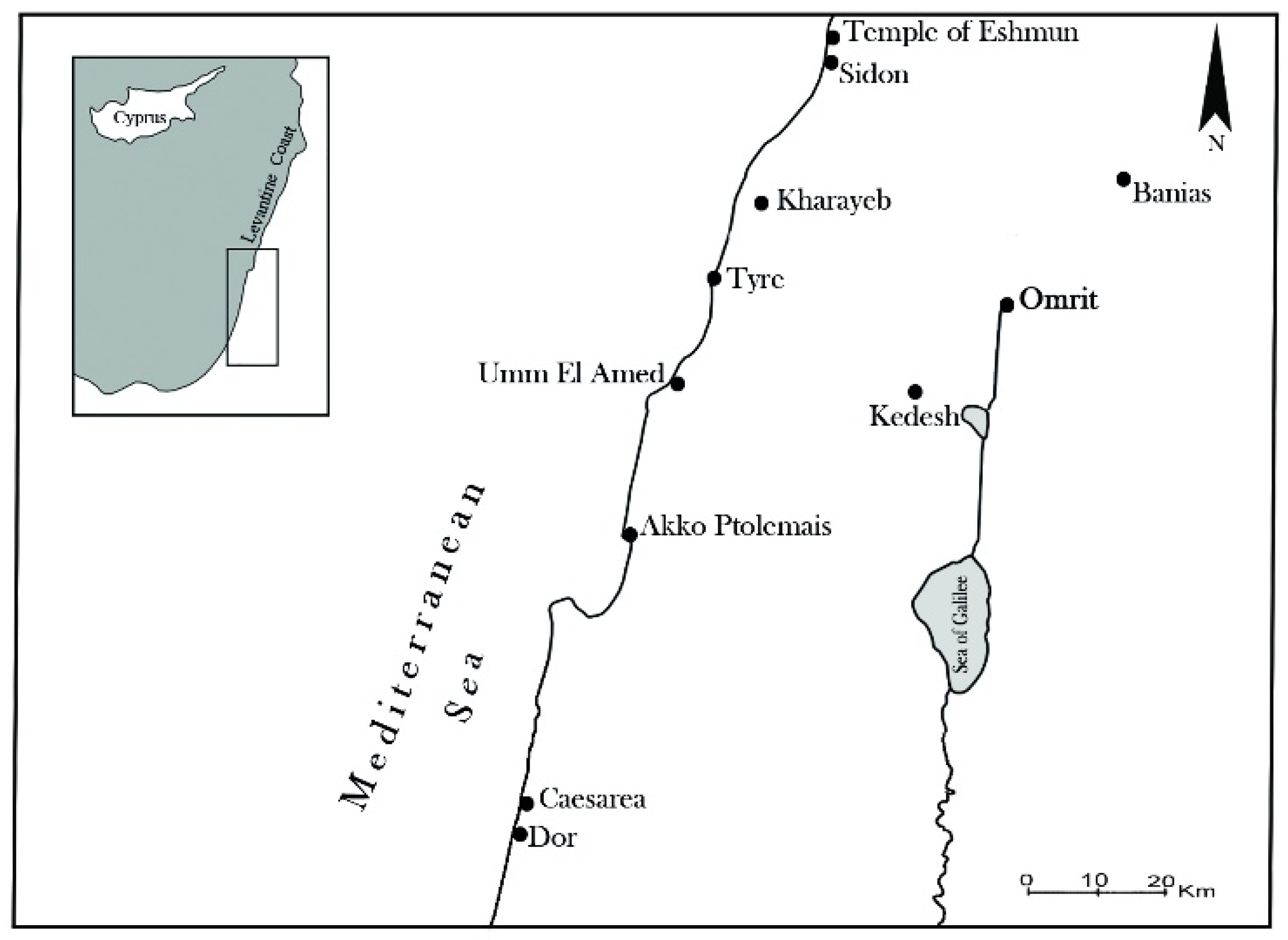

:1. Introduction

2. The Temples at Omrit

3. The Terracotta Figurines from the Omrit Temple

3.1. The Large-Scale Terracottas from Omrit

3.1.1. Description of the Large-Scale Group

3.1.2. Parallels to the Type

4. Discussion: Images of Children in Greek and Roman Sanctuaries

5. Images of Children in the Levant: The Case of Cyprus and Phoenicia

6. The Children of Omrit

Age and Gender

7. Rites of Passage at the Omrit Temple

“The destruction of the object used in the rite may be explained by the fact, observed in Australia, South America, and elsewhere, that sacra may be used only a single time; as soon as a ceremonial phase is ended, they must be destroyed (this being the central idea of sacrifice) or put aside, as if emptied of their powers, and for each new phase there must be new sacra, such as new bodily ornamentation, costumes, or verbal rites”.

8. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The site was excavated by A.J. Overman, D.N. Schowalter, and M.C. Nelson (Macalister College excavations) from 2001 to 2011. The temple, its architecture, stratigraphy and some of the finds have been published (Overman and Schowalter 2011; Nelson 2015; Overman et al. 2021). The finds from the compound are being prepared for publication by the excavators and a team of scholars. I am grateful to the excavators for entrusting the terracottas assemblage to me. |

| 2 | In the recent excavations at Omrit, conducted by Jennifer Gates-Foster, Dan Schowalter, Michael Nelson, Jason Schlude, and Ben Rubin, in the settlement outside the temple compound, more fragments of this type were found. They are currently being studied by the author. |

| 3 | https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF3_2_Enrolment_childcare_preschool.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2022). |

| 4 | Recently a disaster occurred at this celebration, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2021_Meron_crowd_crush (accessed on 11 April 2022). |

References

- Aliqot, Julien. 2009. La vie religieuse au Liban sous l’Empire romain. Beirut: Presses l’Ifpo, Available online: https://books.openedition.org/ifpo/1411?lang=en (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Annan, Bilal. 2013. Parce qu’il a entendu sa voix, qu’il le bénisse: Représentations d’orants et d’officiants dans les sanctuaires hellénistiques d’Oumm el-ʿAmed (Liban). Histoire de l’Art 73: 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Douglass W. 2005. Prehistoric Figurines: Representation and Corporeality in the Neolithic. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ballet, Pascale. 2002. Temples, potiers et coroplathes dans l’Égpte ancienne. Topoi, Suppl. 3. Paper presented at Autour de Coptos. Actes du Colloque Organisé Au Musée De Beaux-Arts de Lyon, Lyon, France, March 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont, Lesley. 2012. Childhood in Ancient Athens. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, Cecelia. 1987. Comparitive votive religion: The evidence of Cyprus, Greece and Etruria. In Gifts to the Gods: Proceedings of the Uppsala Symposium 1985. Boreas 15. Edited by Tullia Linders and Gullog Nordquist. Uppsala: Academia Ubsaliensis, pp. 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, Cecelia. 1993. Temple-Boys: A Study of Cypriote Votive Sculpture 2: Functional Analysis. Stockholm: Stockholm University. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, Cecelia. 1994. Temple-Boys: A Study of Cypriote Votive Sculpture 1: Catalogue. Jonsered: Aströms förlag. [Google Scholar]

- Bel, Nicolas, Giroire Cécile, Gombert-Meurice Florence, and Rutschowscaya Marie-Hélène. 2012. L’orient romain et byzantyn au Louvre. Paris: Louvre éditions. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin, Andrea M. 1999. The Archaeology of Ritual: The Sanctuary of Pan at Banias/Caesarea Philippi. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 315: 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilu, Yoram. 2003. From Milah (Circumcision) to Milah (Word): Male Identity and Rituals of Childhood in the Jewish Ultraorthodox Community. Ethos 31: 172–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, Corinne. 2015. Les enfants de Cadmos: Le paysage religieux de la Phénicie hellénistique. Paris: Éditions de Boccard. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Keith. 2005. The Roman child in sickness and health. In The Roman Family in the Empire: Rome, Italy and Beyond. Edited by Michele George. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- Caneva, Stefano G., and Aurian Delli Pizzi. 2014. Classical and Hellenistic statuettes of the so-called “Temple Boys”: A religious and social reappraisal. In La Presenza Dei Bambini Nelle Religioni Del Mediterraneo Antico: La Vita e la Morte, I Rituali e I Culti Tra Archeologia, Antropologia e Storia Delle Religioni. Edited by Chiara Terranova and Angela Bellia. Rome: Aracne Editrice s.r.l., pp. 495–521. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Maureen. 2018. Infancy and Earliest Childhood in the Roman world: ‘A Fragment of Time’. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castiglione, Marianna. 2020. Pleasure before Duty: Playing and Studying in the Cultic Context of Kharayeb. Pallas 114: 97–126. [Google Scholar]

- Chéhab, Maurice H. 1951–1954. Les terres cuites de Kharayeb. Bulletin du Musée de Beyrouth 10–11: 7–184. [Google Scholar]

- Cosi, Dario M. 2001. L’arketia di Brauron e I Culti Femminili. Bologna: Università di Bologna. [Google Scholar]

- Dasen, Véronique. 2003. Les amulettes d’enfants dans le monde gréco-romain. Latomus, Revue D’études Latines 62: 275–89. [Google Scholar]

- Dasen, Véronique. 2009. Roman birth rites of passage revisited. Journal of Roman Archaeology 22: 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dasen, Véronique. 2014. Iconographie et archéologie des rites de passage de la petite enfance dans le monde romain. Questions méthodologiques. In Life, Death, and Coming of Age in Antiquity: Individual Rites of Passage in the Ancient Near East and Adjacent Regions. Edited by Alice Mouton and Julie Patrier. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, pp. 231–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dasen, Véronique. 2015. Probaskania: Amulets and magic in antiquity. In The Materiality of Magic. Edited by D. Boschung and J. N. Bremmer. Paderborn: Verlag Wilhelm Fink, pp. 177–203. [Google Scholar]

- De Cazonve, Olivier. 2008. Enfants en langes: Pour quells voeux? In Doni Agli Dei. Il Sistema Dei Doni Votivi Nei Santuari. Edited by Giovanna Greco and Bianca Ferrara. Naples: Naus, pp. 271–84. [Google Scholar]

- De Cazonve, Olivier. 2013. Enfants au maillot en contexte cultuel en Italie et en Gaule. Les Dossiers d’Archéologie 356: 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Derks, Ton. 2014. Seeking divine protection against untimely death: Infant votives from Roman Gaul and Germany. In Infant Health and Death in Roman Italy and Beyond. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplement 96. Edited by Maureen Carroll and Emma-Jayne Graham. Portsmouth: Journal of Roman Archaeology, pp. 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Dunard, Maurice. 1978. Verroteries d’enfants dans le temple d’Echmoun a Sidon. Bulletin du Musée de Beyrouth 30: 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dunard, Maurice, and Raymond Duru. 1962. Oumm el-’Amed: Une Ville De L’époque Hellénistique Aux Échelles de Tyr. Paris: Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, Jonathan. 2008. Public Dress and Social Control in Late Republican and Early Imperial Rome. In Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture. Edited by Jonathan Edmondson and Alison Keith. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Erlich, Adi. 2009. The Art of the Hellenistic Palestine. British Archaeological Reports, International Series 2010; Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Erlich, Adi. 2017. Happily Ever After? A Hellenistic Hoard from Tel Kedesh in Israel. American Journal of Archaeology 121: 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlich, Adi. 2019. Terracotta Figurines. In The Excavations of Maresha Subterranean Complex 169. Edited by Ian Stern. Jerusalem: The Nelson Glueck School of Biblical Archaeology, Hebrew Union College, pp. 224–34. [Google Scholar]

- Erlich, Adi. 2021. The Terracotta Figurines. In The Temple Complex at Horvat Omrit 2. The Stratigraphy, Ceramic and Other Finds. Edited by J. Andrew Overman, Daniel N. Schowalter and Michael C. Nelson. Leiden: Brill, pp. 144–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gendelman, Peter. 2015. Chapter 3: The Terracotta Statuary, Masks, Plastic Vases and Portable Altars. In Caesarea Maritima I, Herod’s Circus and Related Buildings, Part 2: The Finds. IAA Reports 57. Edited by Yosef Porath. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, pp. 25–62. [Google Scholar]

- Glinister, Fay. 2017. Ritual and meaning: Contextualising votive terracotta infants in Hellenistic Italy. In Bodies of Evidence: Ancient Anatomical Votives, Past, Present and Future. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 131–46. [Google Scholar]

- Golani, Amir. 2013. Jewelry from the Iron Age II Levant. Fribourg: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Emma-Jayne. 2013. The Making of Infants in Hellenistic and Early Roman Italy: A Votive perspective. World Archaeology 45: 215–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Emma-Jayne. 2014. Infant votives and swaddling in Hellenistic Italy. In Infant Health and Death in Roman Italy and beyond. Edited by Maureen Carroll and Emma-Jayne Graham. Portsmouth: Journal of Roman Archaeology, pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Emma-Jayne, and Jane Draycott. 2017. Introduction: Debating the anatomical votive. In Bodies of Evidence: Ancient Anatomical Votives, Past, Present and Future. Edited by Jane Draycott and Emma-Jayne Graham. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Emma-Jayne, and Maureen Carroll. 2018. Wax Infant Votives in Cyprus: Ancient and Modern Parallels. The Votives Project. Available online: https://thevotivesproject.org/2018/09/13/wax-infants (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Grandjouan, Claireve. 1961. The Athenian Agora VI. Terracottas and Plastic Lamps of the Roman Period. Princeton: American School of Classical Studies at Athens. [Google Scholar]

- Hadzisteliou-Price, Theodora H. 1969. The crouching child and “temple boys”. The Annual of the British School at Athens 64: 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselin Rous, Isabelle, Ludovic Laugier, and Jean-Luc Martinez. 2009. D’Izmir à Smyrne: Découverte d’une Cité Antique. Paris: Musée du Louvre Éditions. [Google Scholar]

- Heyn, Maura K. 2010. Gesture and Identity in the Funerary Art of Palmyra. American Journal of Archaeology 114: 631–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hughes, Jessica. 2017. Votive Body Parts in Greek and Roman Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ilan, David. 2016. The crescent-lunate motif in the jewelry of the Bronze and Iron Ages in the ancient Near East. Paper presented at the 9th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Basel, Switzerland, June 9–13; pp. 137–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kaoukabani, I. 1973. Rapport préliminaire sur les fouilles de Kharayeb. Bulletin du Musée de Beyrouth 26: 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Krencker, Daniel, and Willy Zschietzschmann. 1938. Römische Tempel in Syrien: Nach Aufnahmen Und Untersuchungen Von Mitgliedern Der Deutschen Baalbekexpedition 1901–1904. Berlin and Leipzig: W. De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Lancellotti, Maria Grazia. 2003. I bambino di Kharayeb: Per uno studio storico-religioso del santuario. Studi Ellenistici 15: 341–70. [Google Scholar]

- Langin-Hooper, Stephanie M. 2020. Figurines in Hellenistic Babylonia: Miniaturization and Cultural Hybridity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, Edmund. 1976. Culture and Communication: The Logic by Which Symbols Are Connected. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq, Henri. 1936. Orant, Orante. In Dictionnaire D’archéologie Chrétienne et de Liturgie. Paris: Letouzey et Ané, vol. 12, pp. 2294–98. [Google Scholar]

- Mander, Jason. 2013. Portraits of Children on Roman Funerary Monuments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mazor, Gaby. 2011. The Temple at Omrit: A Study in Architectural and Political Iconography. In The Roman Temple Complex at Horvat Omrit: An Interim Report. Biblical Archaeological Reports International Series 2205; Edited by J. Andrew Overman and Daniel N. Schowalter. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzilli, Francesca. 2018. Rural Cult Centres in the Hauran: Part of the Broader Network of the Near East (100 BC–AD 300). Archaeopress Roman Archaeology 51. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Menegazzi, Roberta. 2014. Seleucia al Tigri. Le Terrecotte Figurate Dagli Scavi Italiani E Americani. Firenze: Le lettere. [Google Scholar]

- Merker, Gloria S. 2000. The Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore: Terracotta Figurines of the Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman Periods (Corinth Vol. XVIII, Part IV). Princeton: American School of Classical Studies at Athens. [Google Scholar]

- Michelau, Henrike. 2015. Recovering a Lost Phoenician Cult Object. BAAL Hors-Série X: 507–28. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Ammerman, Rebecca. 2002. The Sanctuary of Santa Venera at Paestum II. The Votive Terracottas. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Ammerman, Rebecca. 2007. Children at Risk: Votive Terracottas and the Welfare of Infants at Paestum. In Constructions of Childhood in Ancient Greece and Italy. Edited by Ada Cohen and Jeremy B. Rutter. Princeton: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, pp. 131–51. [Google Scholar]

- Mouton, Alice, and Julie Patrier. 2014. Introduction. In Life, Death, and Coming of Age in Antiquity: Individual Rites of Passage in the Ancient Near East and Adjacent Regions. Edited by Alice Mouton and Julie Patrier. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, Arthur. 1996. Les Terres Cuites Votives Du Thesmophorion: De L’atelier Au Sanctuaire. Athènes and Paris: Ecole Française D’Athènes. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Michael C. 2011. A preliminary review of the architecture of Omrit: The temple area. In The Roman Temple Complex at Horvat Omrit: An Interim Report. British Archaeological Reports International Series 2205; Edited by J. Andrew Overman and Daniel N. Schowalter. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Michael C. 2015. The Temple Complex at Horvat Omrit 1. The Architecture. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, Gerhard. 2011. Gesten und Gebärden in der Griechischen Kunst. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke, Jessica. 2007. Perceptions of Culture: Interpreting Greco-Near Eastern Hybridity in the Phoenician Homeland. Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke, Jessica. 2011. ‘Hybrid’ Art, Hellenism and the Study of Acculturation in the Hellenistic East: The Case of Umm el-’Amed in Phoenicia. In From Pella to Gandhara: Hybridisation and Identity in the Art and Architecture of the Hellenistic East. British Archaeological Reports. International Series 2221; Edited by Anna Kouremenos, Sujatha Chandrasekaran and Roberto Rossi. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Oggiano, Ida. 2012. Le sanctuaire de Kharayeb et l’évolution de l’imagerie phénicienne dans l’arrière-pays de Tyr. In La Phénicie Hellénistique: Actes Du Colloque International de Toulouse (18–20 février 2013). Topoi Supplément 13. Edited by Julien Aliquot and Corinne Bonnet. Lyon: Topoi, pp. 239–66. [Google Scholar]

- Oggiano, Ida. 2015. The question of “plasticity” of ethnic and cultural identity: The case study of Kharayeb. BAAL Hors-Série X: 507–28. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, Kelly. 2008. The appearance of the young Roman girl. In Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture. Edited by Jonathan Edmondson and Alison Keith. Toronto and London: University of Toronto Press, pp. 139–57. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, Robin. 2004. Hoards, Votives, Offerings: The Archaeology of the Dedicated Object. World Archaeology 36: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovadiah, Asher, and Yehudit Turnheim. 2011. Roman Temples, Shrines and Temene in Israel. Roma: Giorgio Bretschneider editore. [Google Scholar]

- Overman, Andrew J. 2021. Introduction. In The Temple Complex at Horvat Omrit 2. The Stratigraphy, Ceramic and Other Finds. Edited by J. Andrew Overman, Daniel N. Schowalter and Michael C. Nelson. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Overman, Andrew J., and Daniel N. Schowalter. 2011. Introduction. In The Roman Temple Complex at Horvat Omrit: An Interim Report. British Archaeological Reports International Series 2205; Edited by J. Andrew Overman and Daniel N. Schowalter. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Overman, Andrew J., Daniel N. Schowalter, and Michael C. Nelson, eds. 2021. The Temple Complex at Horvat Omrit 2. The Stratigraphy, Ceramic and Other Finds. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Petsalis-Diomidis, Alexia. 2016. Between the Body and the Divine: Healing Votives from Classical and Hellenistic Greece. In Ex Voto: Votive Giving Across Cultures. Edited by Ittai Weinryb. New York: Bard Graduate Center, pp. 49–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ploug, Gunhild. 1995. Catalogue of the Palmyrene Sculptures, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. Copenhagen: Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. [Google Scholar]

- Prosch, Emily. 2021. The Zeus Altar. In The Temple Complex at Horvat Omrit 2. The Stratigraphy, Ceramic and Other Finds. Edited by J. Andrew Overman, Daniel N. Schowalter and Michael C. Nelson. Leiden: Brill, pp. 307–16. [Google Scholar]

- Queyrel, Anne. 1988. Amathonte IV, Les Figurines Hellénistiques de Terre Cuite. Athènes and Paris: Ecole Française D’Athènes. [Google Scholar]

- Raja, Rubina. 2017. Contextualizing the Sacred in the Hellenistic and Roman Near East: Religious Identities in Local, Regional, and Imperial Settings. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Rawson, Beryl. 2003. Children and Childhood in Roman Italy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal-Heginbottom, Renate. 2017. Herod’s Shrine to Augustus at Omrit: Lamps from the Sanctuary—Sanctuary Lamps? Aram 29: 447–61. [Google Scholar]

- Rozenberg, Sylvia. 2011. Wall Painting Fragments from Omrit. In The Roman Temple Complex at Horvat Omrit: An Interim Report. British Archaeological Reports International Series 2205; Edited by J. Andrew Overman and Daniel N. Schowalter. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Schowalter, Daniel N. 2011. Small Finds and Inscriptions from Omrit. In The Roman Temple Complex at Horvat Omrit: An Interim Report. British Archaeological Reports International Series 2205; Edited by J. Andrew Overman and Daniel N. Schowalter. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Schowalter, Daniel N. 2021. An Inscription on the Paving of the Omrit Temple Complex. In The Temple Complex at Horvat Omrit 2. The Stratigraphy, Ceramic and Other Finds. Edited by J. Andrew Overman, Daniel N. Schowalter and Michael C. Nelson. Leiden: Brill, pp. 211–22. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, Arthur. 2013. Temples and Sanctuaries in the Roman East: Religious Architecture in Syria, Iudaea/Palaestina and Provincia Arabia. Oxford: Oxbow Books. [Google Scholar]

- Steinsapir, Ann I. 2005. Rural Sanctuaries in Roman Syria: The Creation of a Sacred Landscape. Oxford: John and Erica Hedges. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Ephraim. 2010. Figurines and Cult objects of the Iron Age and Persian Period. In Excavations at Dor, Figurines, Cult Objects and Amulets. 1980–2000 Seasons. Edited by Ephraim Stern. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, pp. 3–113. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Susan. 1993. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stucky, Rolf A. 1993. Die Skulpturen aus dem Eschmun-Heiligtum bei Sidon: Griechische, Römische Kyprische und Phönizische Statuen und Reliefs vom 6. Jahrhundert vor Chr. bis zum 3. Jahrhundert nach Chr. Basel: Vereinigung der Freunde antiker Kunst. [Google Scholar]

- Stucky, Rolf A. 2005. Das Eschmun-Heiligtum bei Sidon. Architektur und Inschriften. Basel: Vereinigung der Freunde antiker Kunst. [Google Scholar]

- Talgam, Rina, and Zeev Weiss. 2004. The Mosaics of the House of Dionysos at Sepphoris. Qedem 44. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. [Google Scholar]

- Terranova, Chiara. 2014. La Presenza dei Bambini Nelle Religioni del Mediterraneo Antico: La Vita e la Morte i Rituali e i Culti tra Archeologia, Antropologia e Storia delle Religioni. Roma: Aracne Editrice s.r.l. [Google Scholar]

- Török, László. 1995. Hellenistic and Roman Terracottas from Egypt. Roma: “L’Erma” Di Bretschneider. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Viktor W. 1967. The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlenbrock, Jaimee. 1990. The Coroplast and his Craft. In The Coroplast’s Art, Greek Terracottas of the Hellenistic World. Edited by Jaimee Pugliese Uhlenbrock. New Rochelle: Caratzas, pp. 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- van Gennep, Arnold. 1960. The Rites of Passage. Translated by Monika Vizedom, and Gabrielle L. Caffee. Chicago: University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Susan, and Morris Bierbrier. 1997. Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt. London: British Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Weinryb, Ittai. 2016. Procreative Giving: Votive Wombs and the Study of Ex-votos. In Ex Voto: Votive Giving Across Cultures. Edited by Ittai Weinryb. New York: Bard Graduate Center, pp. 276–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann, Thomas E. J. 1989. Adults and Children in the Roman Empire. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wrede, Henning. 1975. Lunulae im Halsschmuck. In Wandlungen: Studien zur Antiken und Neueren Kunst: Ernst Homann-Wedeking Gewidmet. Edited by Hermann Wrede. Waldsassen-Bayern: Stiftland, pp. 243–54. [Google Scholar]

- Yon, Marguerite. 1994. Les enfants de Kition. In Tranquillitas: Mélanges en l’honneur de Tran tam Tinh. Edited by Marie-Odile Jentel and Giséle Deschênes-Wagner. Québec: Université Laval, pp. 597–609. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Erlich, A. Children in Need: Evidence for a Children’s Cult from the Roman Temple of Omrit in Northern Israel. Religions 2022, 13, 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040362

Erlich A. Children in Need: Evidence for a Children’s Cult from the Roman Temple of Omrit in Northern Israel. Religions. 2022; 13(4):362. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040362

Chicago/Turabian StyleErlich, Adi. 2022. "Children in Need: Evidence for a Children’s Cult from the Roman Temple of Omrit in Northern Israel" Religions 13, no. 4: 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040362

APA StyleErlich, A. (2022). Children in Need: Evidence for a Children’s Cult from the Roman Temple of Omrit in Northern Israel. Religions, 13(4), 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040362