Rituals of Victory: The Role of Liturgy in the Consecration of Mosques in the Castilian Expansion over Islam from Eleventh to Thirteenth Centuries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

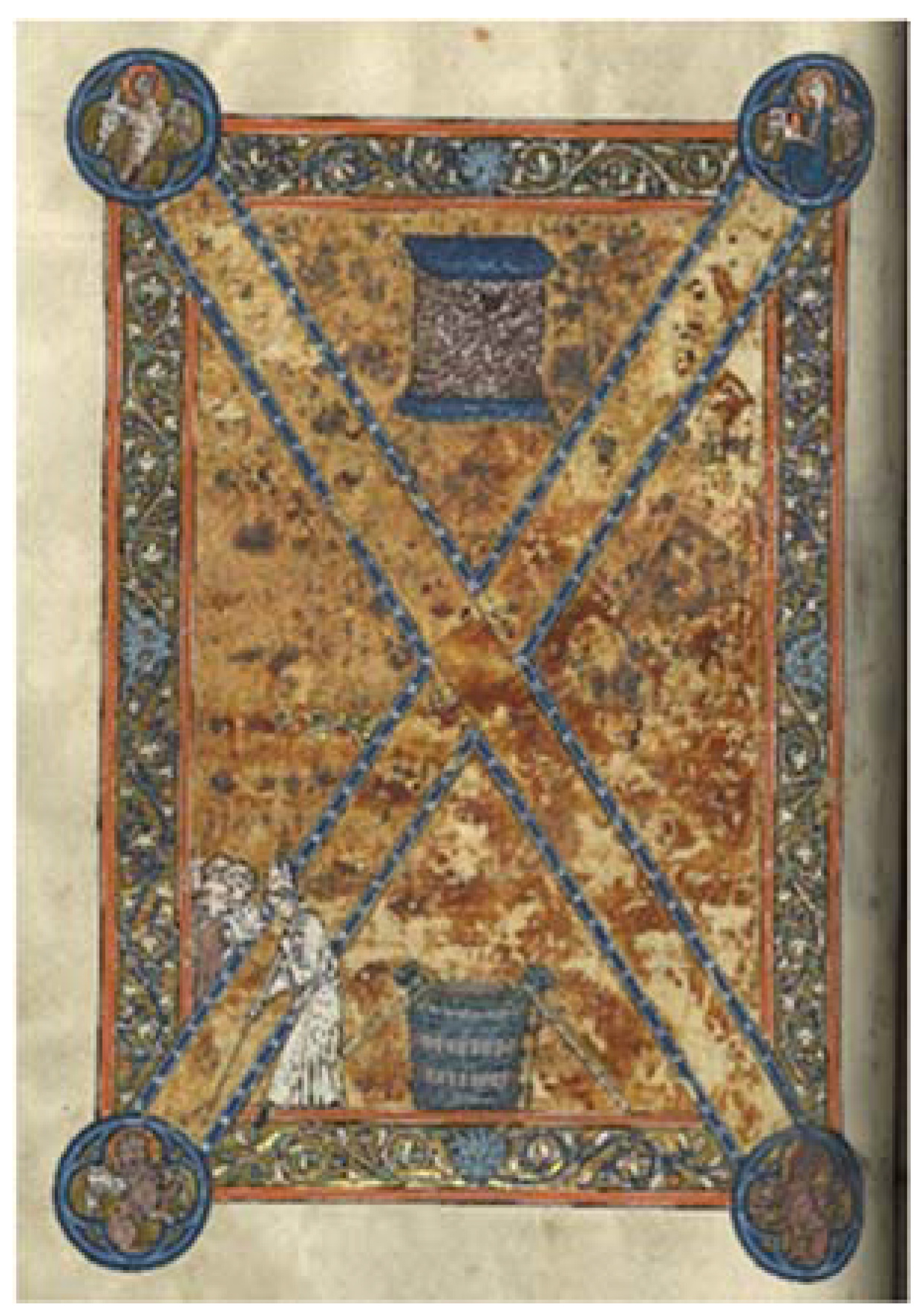

2. Old Visions and New Paths through the Study of Liturgical Manuscripts

3. Rituals of Victory and Sacred Space from Roman Law to Early Middle Ages

4. Civil and Religious Rituals of Victory in Castilian Thirteen-Century Narratives

5. Cleaning the Filthiness of the Prophet the Ordo Dedicationnis Ecclesia Applied to Conversion of Mosques into Churches

“First, twelve crosses must be placed around it on the inside of the walls, so high that no one can reach them with their hands: three on the east, three on the west, three on the south, and three on the north. Second, all the bodies and bones of the dead who were excommunicated, or belonged to another religion, must be removed from the church. Third, twelve candles must be lighted, and each placed upon one of the crosses on nails driven in the middle of the latter. Fourth, ashes, salt, water, and wine must be mixed, and, while the bishop repeats prayers, this must be scattered around the church to purify it. Fifth, the bishop must write with his crozier the a, b, c, of the Greeks and the Latins in the ashes scattered over the floor of the church; and this should be done along the length and breadth of the building, so that these letters may be united in the middle in the form of a cross. Sixth, the bishop must anoint the crosses with chrism and with holy oil. Seventh, incense in many parts of the church must be burned”.

6. Conclusions: Old Rituals for New Conquests

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Almagro Gorbea, Antonio. 2007. De mezquita a catedral: Una adaptación imposible. In La Piedra Postrera. Edited by Alfonso Jiménez Martín. Málaga: Junta de Andalucía, pp. 13–47. [Google Scholar]

- Andrieu, Michel. 1938. Le Pontifical Romain au Moyen Age. T. I: Le Pontifical Romain au XIIe Siècle. Cittá del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostólica Vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Andrieu, Michel. 1940. Le Pontifical Romain au Moyen Âge. T. II : Le Pontifical de la Curie Romaine au XIIIe Siècles. T. III: Le Pontifical de Guillaume Durand (Studi e Testi, 87-88). Cittá del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostólica Vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Arce, Fernando. 2015. La supuesta basílica de San Vicente en Córdoba: De mito histórico a obstinación historiográfica. Al-Qantara 36: 11–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ayala Martínez, Carlos. 2013. On the Origins of Crusading in the Peninsula: The Reigns of Alfonso VI (1065–1109). Imago Temporis. Medium Aevum 7: 225–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala Martínez, Carlos. 2017. The Episcopate and Reconquest in the Times of Alfonso VII of Castile and León. In Between Sword and Prayer Warfare and Medieval Clergy in Cultural Perspective. Edited by Radosław Kotecki, Jacek Maciejewski and John S. Ott. Leyden and Boston: Brill, pp. 207–32. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, Mary. 2007. The Roman Triumph. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buresi, Pascal. 2000. Les conversions d’églises et de mosquées en Espagne aux XIe-XIIe siècles. In Religion et société urbaine au Moyen Âge. Études offertes à Jean-Louis Biget par ses anciens élèves. Edited by Patrick Boucheron and Jacques Chiffoleau. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, pp. 333–50. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Robert. 2001. Las Siete Partidas. Vol. 1: The Medieval Church: The World of Clerics and Laymen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo Capilla, Susana. 2007. Las primeras mezquitas de al-Andalus a través de las fuentes árabes (92/711–170/785). Al-Qanṭara 28: 143–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caseau-Chevallier, Béatrice. 2001. Polemein Lithois. La désacralisation des espaces et des objets religieux païens durant l’Antiquité tardive. In Le Sacré et son Inscription dans l’espace à Byzance et en Occident. Etudes Comparées. Edited by Michel Kaplan. Paris: Presses de la Sorbonne, pp. 61–123. [Google Scholar]

- Catarino, Vicente. 1980. The Spanish Reconquest: A Clunicac Holy war Against Islam? In Islam and The Medieval West. Aspect of Intercultural Relations. Edited by Kalil I. Semaan and Claude Cahen. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 82–109. [Google Scholar]

- Charlo Brea, Luis. 1997. Chrónica Hispana saeculi XIII. Chronia Latina Regnum Castelae. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado Valero, Clara. 1987. Toledo islámico: Ciudad, arte e historia. Toledo: Zocodover. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ors, Álvaro. 1968. El Digesto de Justiniano. Pamplona: Colección Aranzadi, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ors, Álvaro. 1972. El Digesto de Justiniano. Pamplona: Colección Aranzadi, vol. III. [Google Scholar]

- Ecker, Heather. 2003. The great mosque of Córdoba in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Muqarnas 20: 113–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker, Heather. 2014. How to administer a conquered city in al-Andalus: Mosques, parish, churches and parishes. In Under the Influence. Questioning the Comparative in Medieval Castile. Edited by Cyntia Robisnon and Leyla Rouhi. Boston and Leiden: Brill, pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Falque Rey, Emma. 2003. Lucas Tudensis. Chronicom Mundi. Turhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Collado, Ángel, Alfredo Rodríguez González, Isidoro Castañeda Tordera, Andrey Volkov, and Salvador Aguilera López. 2018. Los códices visigótico litúrgicos de la Biblioteca Capitular de Toledo. Toledo: Cabildo Primado Catedral de Toledo. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Valverde, Juan. 1987. Roderici Ximenii de Rada Historia de rebus Hispaniae siue Historia. Turhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Ferotin, Marius. 1904. Le Liber Ordinum en usage dans l’église wisigothique et mozarabe d’Espagne du cinquième au onzième siècle. Paris: Firmin Didot. [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg, Aemilius. 1959. Decretalium Colecctiones. Pars Segunda. Graz: Akademische Druck U-Verlagsanstalt. [Google Scholar]

- Gambra, Andrés. 1998. Alfonso VI: Cancillería, curia e imperio. León: Centro de Estudios de e Investigación san Isidoro, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Sanjuan, Alejandro. 2017. Las conquista de Sevilla por Fernando II (646 h/1248). Nuevas propuestas a través de la relectura de las fuentes árabes. Hispania 77: 11–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gayangos, Pascual. 1863. The History of the Mohammedan Dynasties in Spain. London: Oriental Translation Fund, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- González, Julio. 1986. Reinado y diplomas de Fernando III. V.III. Córdoba: Monte de Piedad y caja de Ahorros de Córdoba. [Google Scholar]

- Kroesen, Justin E. A. 2008. From Mosque to Cathedrals: Converting Sacred Space during the Spanish Reconquest. Mediaevistik 21: 113–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Julie A. 1997. Mosque to church conversions in the Spanish Reconquest. Medieval Encounters 3: 158–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriet, Patrick. 2004. Sanctoral clunisien et sanctoral hispanique au XIIe siècle, ou de l’ignorance réciproque au sycrétisme. À propos d’un lectionnaire de l’office originaire de Sahagún (fin XIIe s.). In Scribere sanctorum gesta. Edited by Étienne Renard, Michel Trigalet, Xavier Hermand and Paul Bertrand. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 209–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, Francisco J. 1996. Los cartularios de Toledo. Catálogo documental. Madrid: Fundación Ramón Areces. [Google Scholar]

- Huici Miranda, Ambrosio. 1953–1954. Al Bayan al-Mugrib fī ijtisār ajbār mulūk al-Andalus Was al Magrib por Ibn Iḏārī al–Marrakušī. Los Almohades. Tetuán: Editorial Marroquí, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Janini, José, Anscari Mundó, and Ramón González. 1977. Manuscritos litúrgicos de la catedral de Toledo. Toledo: Diputación Provincial. [Google Scholar]

- Jódar Mena, Manuel. 2013. De la aljama a la primitiva construcción gótica. Reflexiones a propósito de la Catedral de Jaén en época bajomedieval. Espacio Tiempo y Forma. Serie VII, Historia del Arte 1: 169–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna Paúl, Teresa. 1998. La aljama cristianizada. Memoria de la catedral de Santa María de lla. In Metrópolis Totius Hispaniae. Edited by Alfredo Morales. Sevilla: Ayuntamiento de Sevilla, pp. 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- Levy Provençal, Evariste. 1938. La Peninsule iberique au Moyen âge d’après le Kitāb al-Rāwd al-mītar d’Ibn Abd al-Mun’im al-Hīmyari. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- López-Mayán, Mercedes. 2018. From French-Cluniac to Castillian: A Sacramentary-Pontifical in twelfth century Castile. Scriptorium 72: 251–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lomax, Derek W. 1978. The Reconquest of Spain. New York: Logman. [Google Scholar]

- Mac Cormick, Michel. 1990. Eternal Victory. Triumphal Rulerships in Late Antiquity and Early Medieval West. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mansi, Giovani Domenico. 1778. Sacrorum Concilio Nova Amplisima Colectio. Venice: Antonium Zatta, vol. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Mansilla Reoyo, Demetrio. 1955. La documentación pontifica hasta Inocencio III: 965-1216. Roma: Instituto español de estudios eclesiásticos. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Georges. 2020. La “pérdida y restauración de España” en la historiografía latina de los siglos VIII y IX”. e-Spania. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya Sánchez, Antonio. 1990. Chronica hispana saeculi XII. Pars I. Chronica Adefonsi Imperatoris. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Mehú, Didier. 2007. Histoire et images de la consécration de l’Eglise au moyen âge. In Mises en scéne et mémories de la consecrátion de l’Eglise dans l’Occident médieval. Edited by Didier Mehú. Turnout: Brepols, pp. 15–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mehú, Didier. 2016. L’onction, le voil et la vision ; anthropologie du rituel de dédicase de l’église á l’époque romane. Codex Aquilarensis 32: 63–110. [Google Scholar]

- Menéndez Pidal, Ramón. 1977. Primera Crónica General: Estoria de España que mandó componer Alfonso El Sabio y se continuaba bajo Sancho IV en 1289, II. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Migne, Jacques Paul. 1850. Patrologiae Cursus Completus, Series Latina. Paris: Petit-Montrouge. [Google Scholar]

- Nickson, Tom. 2015. Toledo Cathedral: Building Histories in Medieval Castille. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto Cumplido, Manuel. 1979. Corpus mediaevale cordubense. I. Córdoba: Monte de piedad y Caja de ahorros de Córdoba. [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan, Joseph. 2004. Reconquest and Crusade in Medieval Spain. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo, Eric. 2000. Liturgie et societé au Moyen Age. Paris: Éditions Flammarion. [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo-Bertholon, Benédicte, and Eric Palazzo. 2001. Archéologie et liturgie. L’example de la de dédicace de l’église et de la consécration de l’autel. Bulletin monumental 159: 305–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez de Tudela, Mª Isabel. 1998. Guerra, violencia y terror. La destrucción de Santiago de Compostela por Almanzor hace mil años. En la España Medieval 21: 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pisa, Francisco de. 1605. Descripción de la imperial ciudad de Toledo. Toledo: Pedro Rodríguez. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana Prieto, Augusto. 1987. La documentación pontificia de Inocencio IV (1243–1254). Roma: Instituto español de historia eclesiástica. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, Bernard. 1988. The Kingdom of León-Castile under the king Alfonso VI, 1065-1109. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Remensnyder, Amy. 2000. The Colonization of Sacred Architecture: The Virgin Mary, Mosques, and Temples in Medieval Spain and Early Sixteenth-Century Mexico. In Monks & Nuns, Saints & Outcasts: Religion in Medieval Society; Essays in Honor of Lester K. Little. Edited by Sharon Ann Farmer and Barbara Rosenwein. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Remensnyder, Amy. 2014. La Conquistadora: The Virgin Mary at War and Peace in the Old and New Worlds. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Remensnyder, Amy. 2016. The Entangling and Disentangling of Islam and Christianity in the Churches of Castile and Aragon (11th–16th Centuries). In Transkulturelle Verflechtungsprozesse in der Vormoderne. Edited by Wolfram Drews and Christian Scholl. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 13–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Recio, Juan Francisco. 1976. La iglesia de Toledo en el siglo XII (1086–1208). Toledo: Diputación provincial de Toledo. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Sadía, Juan Pablo. 2004. Las órdenes religiosas y la introducción del rito romano en la Iglesia de Toledo, Una portación desde las fuentes litúrgicas. Toledo: Instituto teológico San Ildefonso. [Google Scholar]

- Rucquoi, Adeline. 2010. Cluny, el camino francés y la reforma gregoriana. Medievalismo 20: 92–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles, Fairchild. 2011. The Stratigraphy of Forgetting: The Great Mosque of Cordova and Its Contested Legacy. In Contested Cultural Heritages. Edited by Elaine Silverman. New York: Springer, pp. 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, Teofilo. 1985. Burgos and the Council of 1080. In Santiago, Saint Denis and Saint Peter. The Reception of the Roman Liturgy in León–Castille in 1080. Edited by Bernard Reilly. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria, Eduardo Carrero. 2005. E mezquita a catedral. La seo de Huesca y sus alrededores entre los siglos XI y XV. In Catedral y Ciudad Medieval en la Peninsula Ibérica. Edited by Eduardo Carrero Santamaría and Daniel Rico Camps. Murcia: Naussica Edición Eléctronica, pp. 35–76. [Google Scholar]

- Saradi, Helen. 2008. The Christianization of Pagan Temples from the Greek Hagiographical Text. In From Temple to Church: Destruction and Renewal of Local Cultic Topography in Late Antiquity. Edited by Stephen Emmel, Johhanes Han and Ulrich Gotter. Leyden and Boston: Brill, pp. 113–34. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Jean-Claude. 2001. Le corps, les rites, les rêves, le temps. Essai D’antropologie Medieval. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Slusser, Michel. 1998. Fathers of the Church: St. Gregory Thaumaturgus Life and Works. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Yan. 2002. La valeur des choses: Le droit romain hors la religion. Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 57: 1431–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treffort, Cecile. 2007. Une consécration «à la lettre». Place, rôle et autorité des textes inscrits dans la sacralisation de l’église. In Mises en scène et mémoires de la consécration de l’église dans l’Occident médiéval. Edited by Didier Mehú. Turhout: Brepols, pp. 219–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ubieto Arteta, Antonio. 1985. Crónica najerense. Valencia: Anúbar. [Google Scholar]

- Valor Piechota, Magdalena, and Isabel Montes Romero Camacho. 2018. La transformación de mezquitas en iglesias. Anuario de Historia de la Iglesia Andaluza 11: 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Versnel, Henk S. 1970. Triumphus: An Inquiry into the Origin, Development and Meaning of the Roman Triumph. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Vives Castell, José. 1942. Consagraciones de iglesias visigodas en domingo. Analecta sacra Tarraconensia 15: 257–64. [Google Scholar]

- Vives, José. 1964. Concilios visigóticos e hispanorromanos. Madrid: Instituto Enrique Flórez. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, Cirylle, and Reinhard Eltze. 1963. Le Pontifical Romano-Germanique du 10e Siècle. Roma: Biblioteca Apostólica Vaticana, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Wienand, Johannes. 2015. O tandem felix civili, Roma, victoria! Civil War Triumphs From Honorius to Constantine and Back. In Contested Monarchy: Integrating the Roman Empire in the 4th Century AD. Edited by Johannes Wienand. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 169–97. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bueno Sánchez, M. Rituals of Victory: The Role of Liturgy in the Consecration of Mosques in the Castilian Expansion over Islam from Eleventh to Thirteenth Centuries. Religions 2022, 13, 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050379

Bueno Sánchez M. Rituals of Victory: The Role of Liturgy in the Consecration of Mosques in the Castilian Expansion over Islam from Eleventh to Thirteenth Centuries. Religions. 2022; 13(5):379. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050379

Chicago/Turabian StyleBueno Sánchez, Marisa. 2022. "Rituals of Victory: The Role of Liturgy in the Consecration of Mosques in the Castilian Expansion over Islam from Eleventh to Thirteenth Centuries" Religions 13, no. 5: 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050379

APA StyleBueno Sánchez, M. (2022). Rituals of Victory: The Role of Liturgy in the Consecration of Mosques in the Castilian Expansion over Islam from Eleventh to Thirteenth Centuries. Religions, 13(5), 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050379