Unchaste Celibates: Clergy Sexual Misconduct against Adults—Expressions, Definitions, and Harms

Abstract

:1. Introduction

God’s interpreters and ambassadors, empowered in His name to teach mankind the divine law and the rules of conduct, and holding, as they do, His place on earth, it is evident that no nobler function than theirs can be imagined. Justly, therefore, are they called not only Angels, but even gods, because of the fact that they exercise in our midst the power and prerogatives of the immortal God (from The Catechism of the Council of Trent—1566).(as cited by Doyle 2006, p. 194; see also Cozzens 2002, pp. 82–84; Leyser 2007; Yocum 2013, pp. 90–117)

the 1983 code [of Canon Law] makes it quite clear that clergy are bound primarily to perfect and perpetual continence [chastity], and to celibacy as a safeguard of this primary obligation. [However] even a celibate cleric can violate continence, and if so, sins against chastity.

2. Background

Background Research and Methods

3. Reframing CSMAA as Professional Sexual Misconduct

3.1. Definition

3.2. Elaboration

- Professional/Clergy sexual misconduct occurs when professionals/clergy—whether male or female…

- misuse, abuse, take advantage of, or disregard

- whether intentionally or through negligence

- their positional and personal power, that they hold by virtue of belonging to a powerful institution or professional organisation,

- to target, over-power, groom, or confuse

- whether subtly or forcefully

- less positionally/personally powerful and most often vulnerable adults,

- for any form of sexual activity with them

- whether legal/consensual or not

- with little or no regard for the harm produced, or the effects that such harm may have on others.

3.3. Summary

4. Unchaste Celibates—A Continuum of Expressions and Severity

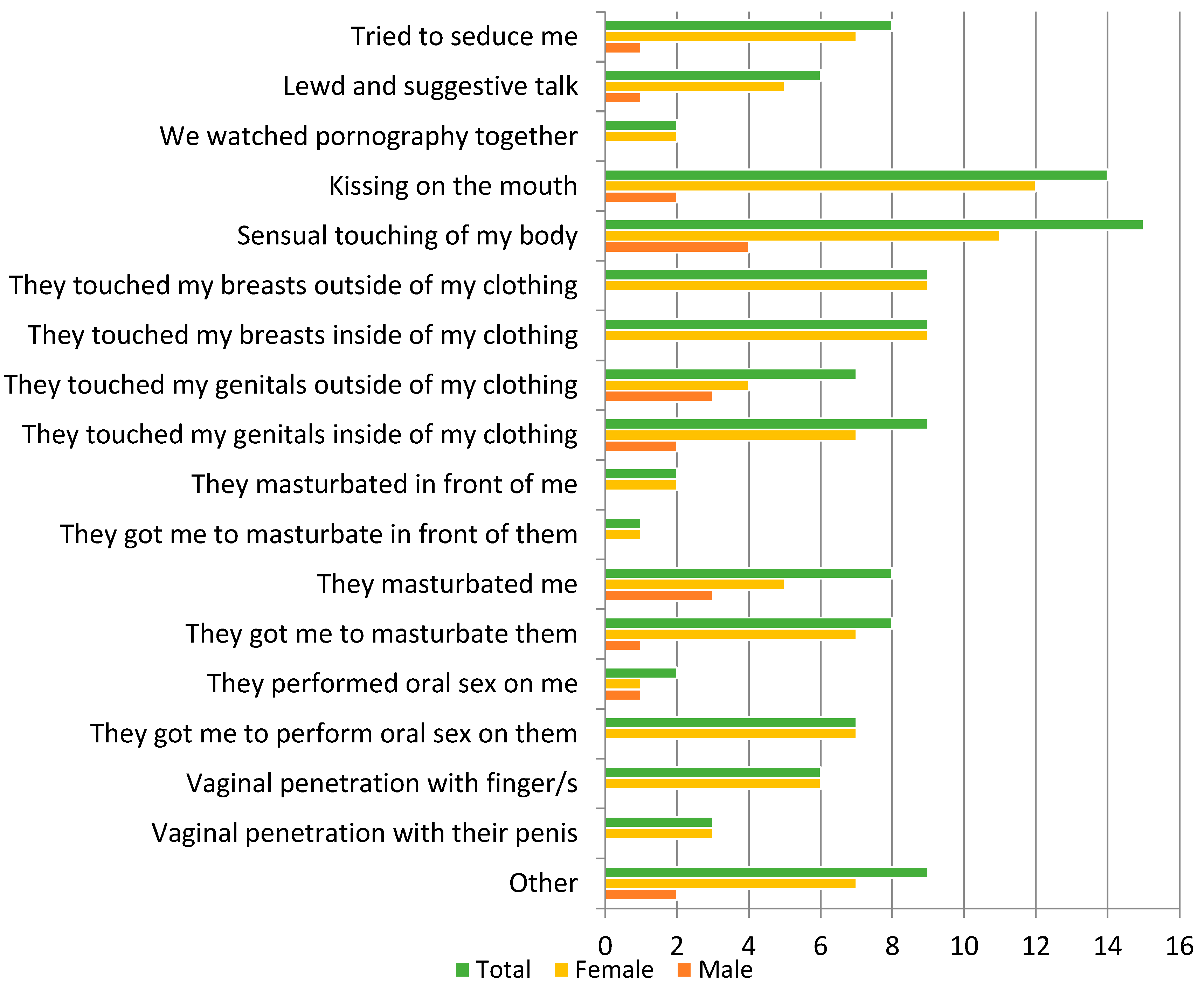

4.1. Clergy Sexual Crimes against Adults

4.2. CSMAA: Clergy Sexual Misconduct against Adults (Some Contexts Now Considered ‘Criminal’)

A clergyperson who, by virtue of occupying a position of authority—as perceived by the congregant or parishioner—and who, because of that position, has knowledge or notice of the emotional dependence or vulnerability of an adult congregant or parishioner, can take advantage of the position of authority and engage in sexual acts with the congregant or parishioner.

Clergy may not force, and the woman may desire him, but he has constructed this context, in which he makes her responsible, whilst relinquishing his responsibility for the boundary-keeping he knows he, as the professional, should maintain.

Therapeutic deception (bodily redemption)—[ ] in one third of the study participants, this form of deception was used where the cleric convinced his victims that “sex (was) a necessary and appropriate part of (their) treatment; (that) sex will make (them) feel better, (and that they, the cleric, was) uniquely able to provide the sexual experience (the victim) need(ed)”.

Spiritual deception: the sacrament of sex—36% of women in [Kennedy’s study] stated in various ways that “God was drawn on to convince women that sexual activity is not only therapeutic but also ‘god-inspired’ or sanctioned”.

Romantic deception—in one third of the cases the women explained how the cleric had fallen in love with them. As such, these are the [CSMAA] events most commonly defined as “affairs”.

I was extremely confused. The priest was telling me this was “love” and said I was “beautiful”. I felt wonderful while he was there, because his definition of what was happening was dominant. But afterwards I felt awful, sinful, depressed, seriously bad and often suicidal (Tanya).

I was depressed and frequently suicidal. In retrospect NONE OF IT WOULD HAVE HAPPENED except that HE INITIATED a sexual relationship. I can say for absolute certain that, if it was up to me at all, I would have followed my sense that he was celibate and out of bounds. I fell for his bull-shit because I was convinced he was truly holy.(Tanya; emphasis, hers)

I say emotionally abused me because everything is on his terms. I only see him when he wants to. If he doesn’t want to see me he avoids me for months and then when he wants to see me he comes back as he pleases. He doesn’t care if I’m crying or asking him to stop, then afterwards he says he loves me then I get so very confused because I love him and I don’t want to lose him. I hope and wish that he will marry me (Winnie).

[He] walked into the meeting room and ran his left hand up under my skirt, grabbed my right breast and planted his mouth on mine. YUK (Jane).

I asked him to stop… As this was the only occasion, I would accept his behaviour was perhaps due to extreme grief & was suffering complete loneness (sic) (Jessica).

I just said “No”……. I think the episode was a once only accident of arousal as far as I was concerned……. (Margaret).

You are immature to think that your secretary finds you an attractive proposition. Offering large sums of money, in this case over $10,000 for holidays etc. along with letters/poems proclaiming love are not what one expects from a parish priest, if parishioners knew they would be appalled by your behaviour. You know I need my job desperately and you tried to exploit my vulnerability as a single struggling parent—you are a pathetic little man (Carol).

He did ask me to marry him which I found utterly remarkable given by the time he asked he was definitely an out gay man in the gay community. I said no, mostly because I was pretty sure his idea of marriage was not mine, and that in reality he would never leave the priesthood because his mother would disown him. We remained friends for the rest of his life and I more or less became his sole confidant. Unfortunately, he never really did get his head out of his rear end because he could never get over his mother (Christine).

4.3. CSAWA: Clergy Sexual Activity with Adults?

4.4. Summary of the Contexts

5. Harms

5.1. Findings and Discussion

5.1.1. Personal Harm

- complex PTSD

- clinical depression

- depression and anxiety

- major depression

5.1.2. Physical Harm

I had a nervous breakdown but continued to work. Whilst she [the mother superior/perpetrator] dyed her hair (worn totally obscured by the veil...so this made no sense if not to fool herself), I was pulling mine out...as a form of self-harm (Maria; in parenthesis, hers).

I was disgusted and afraid, I felt trapped, used as an instrument of gratification. I began vomiting after eating and felt nauseated when I looked at her or even smelt her body odour. I was becoming increasingly depressed and confused, fearful of God’s wrath.

This last episode of abuse by the mother superior during my life among religious caused me to become so ill that I died during surgery and was resuscitated. My reaction to this final effect of the abuse was to run away from the convent as soon as I could get up from my hospital bed.

I have struggled with my chronic worsening health problems all my life (undiagnosed thyrotoxicosis and increasing pain and disability from undiagnosed arthritis) and I am on the verge of being confined to a wheelchair (Maria; in parenthesis, hers).

The whole matter of being disrespected, crushed, vilified, and denigrated for carrying the message of truth—or being a whistle blower, has seriously affected my life and now I have been diagnosed with fibromyalgia and possibly chronic fatigue (Judy).

The Brief Betrayal Trauma Survey (BBTS) assesses exposure to both traumas high in betrayal (such as abuse by a close other) and traumas low in betrayal but high in life-threat (such as an automobile accident). Exposure to traumas with high betrayal was significantly correlated with a number of physical illness, anxiety, dissociation, and depression symptoms. Amount of exposure to other types of traumas (low betrayal traumas) did not predict symptoms over and above exposure to betrayal.

5.1.3. Spiritual Harm

I felt an attempt had been made on my integrity, that my commitment to religious beliefs and work was twisted into a space defined by another person according to his self-interest and need to release (Sue).

He destroyed my sense of safety and my hope of ever going to heaven (Tanya).

This abuse caused me to become divorced from my religion and shunned by my family. I have always felt an outcast (Maria).

I lost a lot of long-time Church “friends” who were really fellow hero-worshippers of the priest. I often feel I was privileged by God to be liberated by the truth, where they have remained under illusions. They didn’t want their sense of safety in the Church to be threatened. I don’t have any illusions about the Church or priests, but a strong belief in God’s holiness. Unfortunately, however, I seem to have lost fairly permanently my sense of safety in the world. I manage OK, but I suffer from chronic high anxiety (Tanya).

The impact on Catholic victims is unique and, in the opinion of some experts, particularly devastating precisely because the abuser is a priest… Many victims experience a kind of toxic transference and experience in their sexual abuse a form of spiritual death.

5.1.4. Psychological Harm

I was naturally anxious and unable to suppress the anxiety till I began to inappropriately express frustration, mostly in community. When offered to have therapy I was diagnosed with major depression (Maria).

After a time of great struggle and consequent growing dependence on substance abuse, in my case alcohol, I began my journey of recovery (Edith).

CLERICAL SEXUAL ABUSE DESTROYS LIVES AND IT HAS SEVERELY DAMAGED MINE (Judy—capitalisation hers).

A lot of the therapy in the first year or two was to help me cope with how the Provincial and others known to the priest were reacting to me (Tanya).

Having therapy has helped me immensely to acknowledge the truth of what happened. This has freed me from feeling restricted by the guilt and shame. It has enabled me to revisit my childhood, to forgive and to re-engage with life as a religious (Teresa).

I ended up involved in a twelve Step Program AA, [and] my life has slowly picked up... My husband has had great difficulties coming to terms with it and yet we have stuck together through it all (Edith).

I was fortunate to find a woman who loved me unconditionally (Andy).

5.1.5. Relational Harm

Following the abuse, I acted homosexual with other males but denied it externally (James).

My wife and I struggled sexually from the first year of our marriage 15 years ago. Now I am confused sexually. I find other males sexually attractive but remain in a Hetro (sic) marriage whilst living alone apart from my wife who lives alone too. I have had continual problems with power figures including managers, clergy, and so on. I prefer to live alone but need others loosely around me. I hate feeling controlled by anyone including checkout workers at a supermarket (James).

Impact on my marriage has been huge and may be irreparable. While he has been incredibly supportive, the psychological effects on me continue to impact on our relationship and he feels he cannot “put up” with these anymore. He is still angry that I did not “trust” him and tell him sooner. I told him almost 20 years after we were married. What happened to me stole my adulthood and developing positive relationships with people in general, and men in particular. I feel so icky to have actually married and had children (Wendy).

My friendships are becoming difficult because I’m living a secret life that I can’t share with my friends. If I have problems, I have no one to ask for advice and if I am happy, I have no one to share the joy with (Winnie).

Even without wanting it to, [CSMAA] sets up barriers. People who have not experienced it have no idea of the ways it affects a person, and because it’s so hard to discuss, it just kind of gets in the way of everyday relationships (Sarah).

At 65 years old I am still trying to accept myself as a good and worthwhile person (Scott).

I cannot respect priests now any more than I respect any other people. The word “Father” sticks in my throat (Tanya).

I trusted you and I believed you would respect my trust. It took me a long time to rebuild my trust in men, in particular, although I am much more cautious (Teresa).

5.1.6. Practical Harm

I have struggled with my chronic worsening health problems all my life and I am on the verge of being confined to a wheelchair. I have never been able to work hence I’ve never been able to put away savings for my old age and possible infirmity. I have been in receipt of a disability support pension all my life since age 30. I am in debt and insolvent and am having to negotiate with the financial institutions to which I owe money to be relieved of my debts so I will not lose my house. My present most urgent needs are: (a) be relieved of my debts (b) be strong enough in body and positive enough in mind to survive surgery (Maria).

It was their religious order that took from me every prospect of a career and a stable financial life by abducting me at 1610 then abusing me as a child and as an adult until my health suffered, never to recover (Maria).

If you truly repent give me of this world’s goods and security...which you say you do not care about yet have much of! I need some financial relief so I can have surgery on the body I had, once strong and fit as that of a junior gymnast and ballet dancer...you stole that body from me! You abused that body until it died during surgery and was revived. Give me back my strength. Give me the money my poor mother gave you as my dowry that should have been returned to me when I left your convent so I could start my life again. I need you to pay the doctors to mend my broken body! I need to be funded at the highest level of medical and hospital cover...that insurance you cancelled and told me to pay myself when all I had was a Disability Pension of $42.70 a fortnight and was so very ill to the point of death. That’s what I want, that the Church compensate me for ruining my body and mind then pay for the best doctors and medical treatment to restore me... (Maria).

I also lost my job and had to find part time work, but didn’t know why, and then I was not able to work anymore, so that was when even part time work didn’t last and it all came crashing in (Ann).

I also know that the Order must replace my massive loss of income/super from having to resign 20 years early. They need to be able to be taught to acknowledge this (Ann).

Ever since the abuse I have suffered financially for many reasons. I volunteered three years as a missionary too. I have lost so many jobs due to issues with authority and I don’t have a solid financial future due to the abuse and due to an ineffective church and Towards Healing.I need financial security into the future as I may have another 25 to 30 years of life in me (James).

I had to leave my studies and I so wanted to work as a missionary sister (Grace).

I felt I had to leave a work position that I truly loved because working where I did with this person in a power position became untenable (Sue).

5.2. Summary of Harms

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

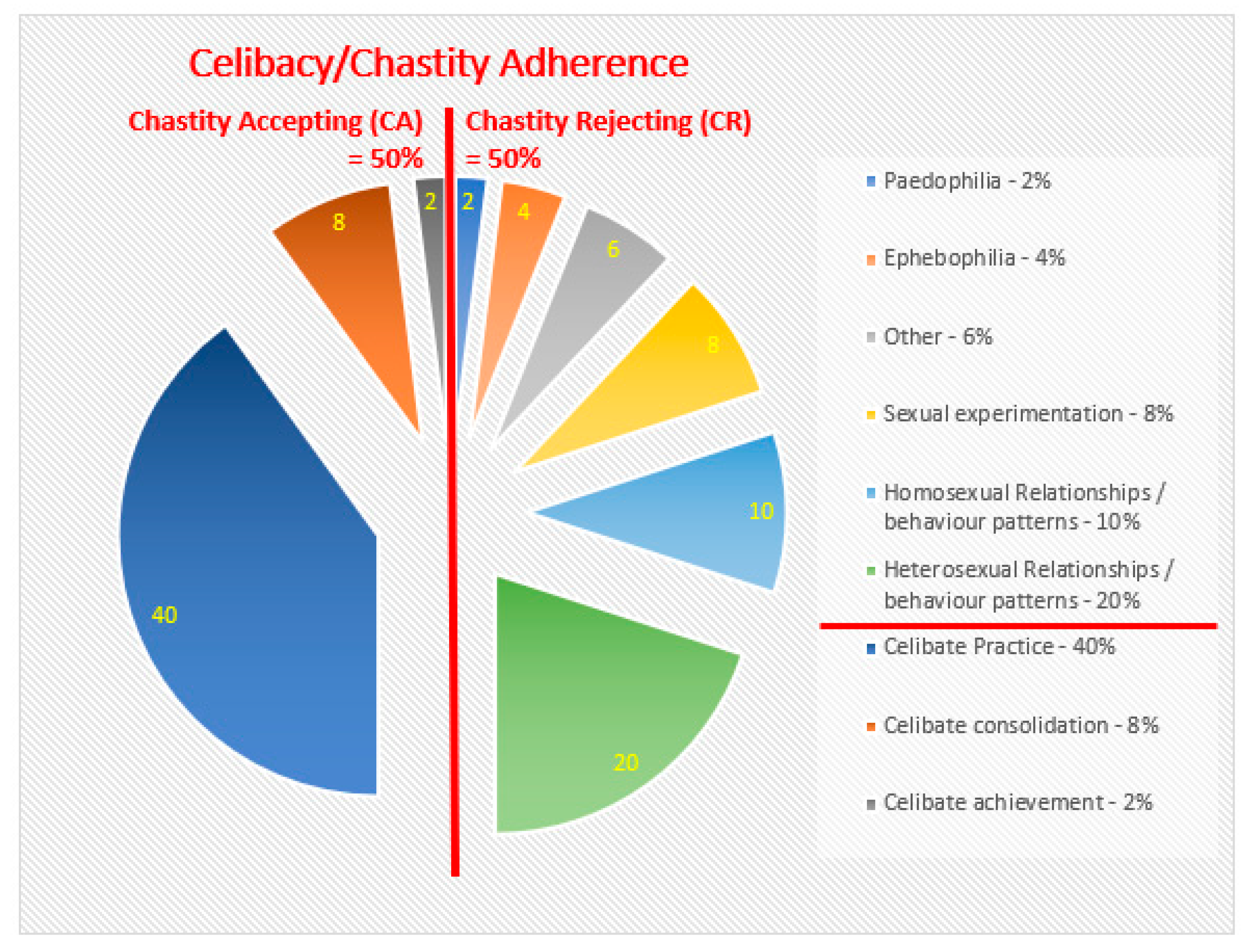

| 1 | Due to the controversial nature of Sipe’s estimates, the following explanations and additions were deemed necessary: For Sipe’s explanations for his estimates and a validation thereof, see (Sipe 1995, pp. 66, 75–79; 2003, pp. 44–50). Sipe’s (1995) estimates were based on his work with “over 1500 Catholic priests”. Furthermore, he worked with and utilised a great deal of data from “25 psychoanalysts, psychiatrists, psychologists and historians”, checking figures with “10 groups of priests in diocesan and Religious settings” (Sipe 1995, p. 66). In his 2003 book, the sample had increased to 2775 priest from “five levels of observation (Sipe 2003, pp. 49–50). Sipe’s ‘estimates’ were also supported by various cardinals, including Cardinal Josk Sanchez, Prefect of the Congregation for the Clergy in Rome (Sipe 1994, p. 134), as well as many leaders from the various Religious Orders. As to other sources, Sheila Murphy’s, A Delicate Dance: Sex, celibacy, and relationships among Catholic clergy and religious, revealed the following: Of the female participants, 49% acknowledged sexual behaviours. Of this 49%, 39% reported only male partners; 35% only female partners and 29% both male and female partners. As for the male participants, 62% reported being “sexually active” and of these 58% said that their partners were exclusively female, while 32% said they were exclusively male (Murphy 1992, pp. 60–63). The John Jay Report also provided data concerning clergy sexual misconduct against adults in this summary:

Similar figures can be found in a 1995 report by Spanish psychologist, Pepe Rodriguez:

It needs to be noted, however, none of the given studies can be generalised to the entire population of clergy. Not until a complete study of all clergy (Brothers and Sisters included) is done, and all clergy answer honestly, shall we never know with absolute certainty whether the 50% figure is fully accurate. But no one in the church or in academia is contradicting these claims/estimates and if anything, they are being ‘supported’. |

| 2 | For the complete outlines of the research design, methods, and underlying methodological framework, including limitations, see (de Weger 2016, pp. 60–70) and (de Weger 2020, pp. 129–50). |

| 3 | Please note that only pseudonyms have been used here and in the foundational studies. |

| 4 | It was not possible to fully outline these findings here. For a full discussion on these see (de Weger 2016). |

| 5 | This is my own definition. While simpler ones exist, I felt the need to be as unambiguous and as inclusive as possible. It may well be developed or changed in the future. |

| 6 | For fuller descriptions of the scenarios either side of 3–11, see (de Weger 2020, pp. 48–55, 262–64). For another list, similar but different, see Benyei (1998, pp. 65–72). |

| 7 | The very important question of ‘What is love’ is far beyond the scope of this study even though there was a desire to include a discussion on the topic. Suffice it to say here, this study found the best definition of adult human love in Fromm’s mid-20th classic, The Art of Loving (Fromm 1956). It also found similar content on appropriate mature and logical concepts in Karen Lebacqz short article “Appropriate Vulnerability: A Sexual Ethic for Singles” (Lebacqz 1987). For a definition of consent, see Marilyn Peterson book At Personal Risk (Peterson 1992, p. 124). |

| 8 | See https://maltesemarriedcatholicpriest.wordpress.com/?s=Married+Priest (accessed on 10 November 2021). (As of 17 May 2020, this site has ceased to operate, however, the content remains). |

| 9 | At the time, Margaret was a Christian Chaplain at the hospital where the event occurred. She was not ‘disturbed’ by the indecent assault of the priest who was a patient there, but understood the context. She also knew of his personal history of previous CSMAA. Also, it was clear in this case given the circumstances she was an ‘equal’ to the priest/patient. |

| 10 | The following is a paraphrasing of Maria’s testimony dealing with her abduction: These Sisters had abducted Maria from their Hostel for Girls, where, due to her mother’s ill health, she had been sent to live. When she was 16 the Sisters allegedly forged documents and shipped her off to [country] and forced her to become a Sister, herself, enduring abuse there during the training. Once professed as a Sister, she was returned to Australia. |

References

- Aguon, Mindy. 2017. Vatican Tribunal Note-Taker Accused of Sexual Harassment. The Guam Daily Post. August 3. Available online: https://www.postguam.com/news/local/vatican-tribunal-note-taker-accused-of-sexual-harassment/article_5a5c37bc-782b-11e7-911a-3b489b4014ee.html (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Anderson, Jane. 2006. Priests in Love: Roman Catholic Clergy and Their Intimate Relationships. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, Gordon L. 1994. Sexual Behavior by Male Clergy with Adult Female Counselees: Systemic and Situational Themes. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity 1: 103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyei, Candice R. 1998. Understanding Clergy Misconduct in Religious Systems: Scapegoating, Family Secrets, and the Abuse of Power. Binghamton: The Haworth Pastoral Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bordisso, Lou A. 2011. Sex, Celibacy and Priesthood. Bloomington: iUniverse. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke, Patrice, Tony Ward, and Chelsea Rose. 2012. Expertise and Sexual Offending: A Preliminary Empirical Model. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27: 2391–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, Stephen. 2008. The Impact of Sexual Abuse on Sexual Identity Formation in Gay Men. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 17: 359–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, Kathryn R. 2010. Understanding the Abuse of Adults by Catholic Clergy and Religious. Loganville: Open Heart Life Coaching, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- CCL. 1983. The Code of Canon Law. Book II—The People of God; Part II—The Hierarchical Constitution of the Church; Section I—The Supreme Authority of the Church (Can. 330–367); Chapter I—The Roman Pontiff and the College of Bishops; Article I.—The Roman Pontiff. Available online: https://juiciobrennan.com/files/bishopselection/code_of_canon_law_1983.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Celenza, Andrea. 1991. The misuse of countertransference love in sexual intimacies between therapists and patients. Psychoanalytic Psychology 8: 501–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celenza, Andrea. 2004. Sexual Misconduct in the Clergy: The Search for the Father. Studies in Gender and Sexuality 5: 213–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibnall, John T., Ann Wolf, and Paul N. Duckro. 1998. A National Survey of the Sexual Trauma Experiences of Catholic Nuns. Review of Religious Research 40: 142–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-White, Pamela. 1990. Books: Is Nothing Sacred? When Sex Invades the Pastoral Relationship. The Christian Century 107: 156–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzens, Donald B. 2002. Sacred Silence: Denial and the Crisis in the Church. Collegeville: The Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crisp, Beth R. 2012. The Spiritual Implications of Sexual Abuse: Not Just an Issue for Religious Women? Feminist Theology 20: 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Fuentes, Nanette. 1999. Hear Our Cries: Victim-Survivors of Clergy Sexual Misconduct. In Bless Me Father for I Have Sinned: Perspectives on Sexual Abuse Committed by Roman Catholic Priests. Edited by Thomas G. Plante. Westport: Praeger, pp. 135–70. [Google Scholar]

- de Weger, Stephen E. 2016. Clerical Sexual Misconduct Involving Adults within the Roman Catholic Church. Master’s thesis, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia. Available online: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/96038/4/Stephen%20de%20Weger%20Thesis.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- de Weger, Stephen E. 2020. Reporting Clergy Sexual Misconduct against Adults to Roman Catholic Church Authorities: An analysis of Survivor Perspectives. Ph.D. dissertation, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia. Available online: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/205923/ (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- de Weger, Stephen E. 2022. Insincerity, Secrecy, Neutralisation, Harm: Reporting Clergy Sexual Misconduct against Adults—A Survivor-Based Analysis. Religions 13: 309. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040309 (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- de Weger, Stephen E., and Jodi Death. 2017. Clergy Sexual Misconduct Against Adults in the Roman Catholic Church: The Misuse of Professional and Spiritual Power in the Sexual Abuse of Adults. Journal for the Academic Study of Religion 30: 227–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGeorge, Gail. 2019. Women Religious Shatter the Silence about Clergy Sexual Abuse of Sisters. Global Sisters Report–National Catholic Reporter. January 21. Available online: https://www.globalsistersreport.org/news/trends/women-religious-shatter-silence-about-clergy-sexual-abuse-sisters-55800 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Douthat, Ross. 2018. #MeToo Comes for the Archbishop. The New York Times. June 23. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/23/opinion/sunday/cardinal-theodore-mccarrick-metoo-archbishop.html (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Doyle, Thomas P., A. W. Richard Sipe, and Patrick Wall. 2006. Sex Priests and Secret Codes: The Catholic Church’s 2000-Year Paper Trail of Sexual Abuse. Los Angeles: Bonus Books. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, Thomas P. 2006. Clericalism: Enabler of Clergy Sexual Abuse. Pastoral Psychology 54: 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, Marilyn. 2007. Asceticism and monasticism, II: Western. In The Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 2—Constantine to c. 600. Edited by Augustine Casiday and Frederick W. Norris. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 669–90. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, J. D. 2018. Benedict, Viganò, Francis, and McCarrick: Where Things Stand on Nuncio’s Allegations. CNA (Catholic News Agency). September 3. Available online: https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/benedict-vigan-francis-and-mccarrick-where-things-stand-on-nuncios-allegations-42199 (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Flynn, Kathryn A. 2003. The Sexual Abuse of Women by Members of the Clergy. North Carolina: McFarland and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Fones, Calvin S. L., Stephen B. Levine, Stanleye Althof, and Candace B. Risen. 1999. The sexual struggles of 23 clergymen: A follow-up study. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 25: 183–95. [Google Scholar]

- Fortune, Marie M. 1989. Is Nothing Sacred? When Sex Invades the Pastoral Relationship. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Freyd, Jennifer J., Bridget Klest, and Carolyn B. Allard. 2005. Betrayal Trauma: Relationship to Physical Health, Psychological Distress, and a Written Disclosure Intervention. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation 6: 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frishberg, Hannah. 2021. Pope Francis says ‘sins of the flesh’ aren’t that ‘serious’. New York Post. December 8. Available online: https://nypost.com/2021/12/08/pope-says-extramarital-sex-sins-arent-that-serious/ (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Fromm, Erich. 1956. The Art of Loving. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbioneta, Claudia, James R. Faulconbridge, Graeme Currie, Ronit Dinovitzer, and Daniel Muzio. 2019. Inserting Professionals and Professional Organizations in Studies of Wrongdoing: The Nature, Antecedents and Consequences of Professional Misconduct. Human Relations (New York) 72: 1707–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, Diana R. 2006. When Wolves Wear Shepherds’ Clothing: Helping Women Survive Clergy Sexual Abuse. Social Work & Christianity 33: 1–35. Available online: http://www.nacsw.org/Publications/GarlandArticle.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Garland, Diana R., and Christen Argueta. 2010. How Clergy Sexual Misconduct Happens: A Qualitative Study of First-Hand Accounts. Social Work & Christianity 37: 1–27. Available online: https://www.baylor.edu/content/services/document.php/96038.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Garland, Diana R, and Christen Argueta. 2011. Unholy touch: When church leaders commit acts of sexual misconduct with adults. In the Church Leader’s Resource Book for Mental Health and Social Problems. Edited by Cynthia Franklin and Rowena Fong. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 405–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gonsiorek, John. C. 1995. Epilogue. In Breach of Trust: Sexual Exploitations by Healthcare Professionals and Clergy. Edited by John C. Gonsiorek. London: SAGE Publications, pp. 392–93. [Google Scholar]

- Gregoire, Jocelyn, and Chrissy Jungers. 2004. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity among Clergy: How Spiritual Directors Can Help in the Context of Seminary Formation. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity 11: 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross Schaefer, A. 1994. Combating Clergy Sexual Misconduct. Risk Management 41: 32–37. Available online: http://www.questia.com/library/1P3-772190/combating-clergy-sexual-misconduct (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- ITC (International Theological Commission). 1973. Catholic Teaching on Apostolic Succession. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/cti_documents/rc_cti_1973_successione-apostolica_en.html (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- John Jay Report. 2004. John Jay College of Criminal Justice. The Nature and Scope of the Problem of Sexual Abuse of Minors by Catholic Priests and Deacons in the United States: A Research Study Conducted by the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. Available online: http://www.philvaz.com/ABUSE.PDF (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- John Paul II. 1992. Pastores Dabo Vobis: To the Bishops, Clergy and Faithful on the Formation of Priests in the Circumstances of the Present Day. Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_jp-ii_exh_25031992_pastores-dabo-vobis.html (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Jorgenson, L. M. 1995. Sexual Contact in Fiduciary Relationships: Legal Perspectives. In Breach of Trust: Sexual Exploitations by Healthcare Professionals and Clergy. Edited by John. C. Gonsiorek. London: SAGE Publications, pp. 237–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, Margaret. 2009. The Well From Which We Drink Is Poisoned: Clergy Sexual Exploitation of Adult Women. Ph.D. thesis, London Metropolitan University, London, UK. ProQuest: U501735. [Google Scholar]

- Kluft, Richard P. 2010. Ramifications of Incest: The role of memory. Psychiatric Times 27: 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lebacqz, Karen. 1987. Appropriate Vulnerability: A Sexual Ethic for Singles. The Christian Century 104: 435–38. [Google Scholar]

- Leyser, Henrietta. 2007. Clerical purity and the re-ordered world. In the Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 4—Christianity in Western Europe c. 1100–c. 1500. Edited by Miri Rubin and Walter Simons. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lievore, Denise. 2003. Non-Reporting and Hidden Recording of Sexual Assault: An International Literature Review. Australian Government, Australian Institute of Criminology for the Office of the Status of Women. Available online: http://www.aic.gov.au/publications/previous%20series/other/41-60/non-reporting%20and%20hidden%20recording%20of%20sexual%20assault.html (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Loftus, John. A. 1994. Understanding Sexual Misconduct by Clergy: A Handbook for Ministers. Washington, DC: The Pastoral Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loya, Rebecca M. 2015. Rape as an Economic Crime: The Impact of Sexual Violence on Survivors’ Employment and Economic Well-Being. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 30: 2793–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, William P. 2004. Separation, Neutrality, and Clergy Liability for Sexual Misconduct. Brigham Young University Law Review 5: 1921–44. Available online: http://lawreview.byu.edu/archives/2004/5/6MAR-FIN.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- McLaughlin, Barbara R. 1994. Devastated spirituality: The impact of clergy sexual abuse on the survivor’s relationship with god and the church. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity: The Journal of Treatment & Prevention 1: 145–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEP (Maltese Ecclesiastical Province). 2014. On Cases of Sexual Abuse in Pastoral Activity: Statement of Policy and Procedures in Cases of Sexual Abuse. Available online: http://ms.maltadiocese.org/WEBSITE/2014/Safeguarding%20Policy%202014.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Mason, Fiona, and Zoe Lodrick. 2013. Psychological consequences of sexual assault. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology 27: 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, E. Ellen, Julia C. Smith, Sharjeel Yonus Farooqui, and Alina M. Surís. 2014. Unseen Battles: The Recognition, Assessment, and Treatment Issues of Men with Military Sexual Trauma (MST). Trauma, Violence and Abuse 15: 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, Sheila M. 1992. A Delicate Dance: Sex, Celibacy, and Relationships among Catholic Clergy and Religious. New York: Crossroad. [Google Scholar]

- Muzio, Daniel, James R. Faulconbridge, Claudia Gabbioneta, and Royston Greenwood. 2016. Bad apples, bad barrels and bad cellars: A “boundaries” perspective on professional misconduct. In Organizational Wrongdoing: Key Perspectives and New Directions. Edited by Don Palmer, Royston Greenwood and Kirstin Crowe-Smith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Gov (New South Wales Government). 2012. Crimes Act 1900 No 40. Available online: https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/inforce/current/act-1900-040#pt.3-div.10 (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Orzeck, Tricia L., Ami Rokach, and Jacqueline Chin. 2010. The Effects of Traumatic and Abusive Relationships. Journal of Loss and Trauma: International Perspectives on Stress & Coping 15: 167–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Marilyn R. 1992. At Personal Risk: Boundary Violations in Professional-Client Relationships. New York: Norton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Richard H., Jin Nam Choi, and Amaram D. Vinokur. 2002. Links in the chain of adversity following job loss: How financial strain and loss of personal control lead to depression, impaired functioning, and poor health. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 7: 302–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provost, James. H. 1992. Some Canonical Considerations Relative to Clerical Sexual Misconduct. The Jurist 52: 615–41. Available online: https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/juristcu52&i=620 (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Reisinger, Doris. 2022. Reproductive Abuse in the Context of Clergy Sexual Abuse in the Catholic Church. Religions 13: 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, Mary Ann. 1993. The Legitimation of the Abuse of Women in Christianity. Feminist Theology 4: 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Commission. 2015. Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. Case Study 31: Public Hearing: Day 156. Available online: http://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/case-study/67173cc9-3256-4cf9-8564-8df9f7357195/case-study-31,-august-2015,-sydney (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Rubenson, Samuel. 2007. Asceticism and monasticism, I: Eastern. In The Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 2—Constantine to c. 600. Edited by Augustine Casiday and Frederick W. Norris. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 637–68. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, Janice. 1993. Out of Bounds: Sexual Exploitation in Counselling and Therapy. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, Peter. 1989. Sex in the Forbidden Zone: When Men in Power—Therapists, Doctors, Clergy, Teachers and Others—Betray Women’s Trust. Los Angeles: J.P. Tarcher. [Google Scholar]

- Schilit, Howard M. 1984. Deviant Behaviour and Misconduct of Professionals. Woman CPA 46: 20–24. Available online: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/wcpa/vol46/iss2/7 (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Shupe, Anson D. 1995. The Name of All That’s Holy: A Theory of Clergy Malfeasance. Westport: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Sipe, A. W. Richard. 1994. The Problem of Sexual Trauma and Addiction in the Catholic Church. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity 1: 130–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipe, A. W. Richard. 1995. Sex, Priests, and Power: Anatomy of a Crisis. New York: Brunner/Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- Sipe, A. W. Richard. 2003. Celibacy in Crisis: A Secret World Revisited. New York: Brunner-Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sipe, A. W. Richard. 2008. Preliminary Considerations for the Understanding of the Genealogy of Sexual Abuse by Catholic Clergy. Richard Sipe: Celibacy, Sex, and the Catholic Church. Available online: http://www.awrsipe.com/click_and_learn/2008-10-preliminary_considerations.html (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Sipe, A. W. Richard. 2016. Letter to Bishop McElroy. Richard Sipe: Celibacy, Sex, and the Catholic Church. Available online: http://www.awrsipe.com/Correspondence/McElroy-2016-07-28-rev.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- The Pillar. 2022. Stika, Knoxville diocese, sued for alleged rape cover-up. The Pillar. February 23. Available online: https://www.pillarcatholic.com/p/stika-knoxville-diocese-sued-for?utm_source=url (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- Toben, Bradley, and Kris Helge. 2013. Clergyperson Sexual Misconduct with Congregants or Parishioners: Past Attempts to Impose Civil and Criminal Liabilities and a Proposed Criminal Law to Increase the Likelihood of Criminal Punishment of Perpetrators. In Clergy Sexual Abuse: Social Science Perspectives. Edited by Claire M. Renzetti and Sandra Yocum. Boston: Northeastern University Press, pp. 144–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tschan, Werner. 2014. Professional Sexual Misconduct in Institutions: Causes and Consequence, Prevention and Intervention. Gottinghem: Hogrefe Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Victorian Inquiry. 2013. Victorian Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and Other Organisations. Chair’s Forward. Available online: https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/images/stories/committees/fcdc/inquiries/57th/Child_Abuse_Inquiry/Report/Inquiry_into_Handling_of_Abuse_Volume_1_FINAL_web.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Villiers, Janice D. 1996. Clergy malpractice revisited: Liability for sexual misconduct in the counseling relationship. Denver University Law Review 74: 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Vos Estis Lux Mundi. 2019. Apostolic Letter issued Motu Proprio by the Supreme Pontiff. Francis: VOS ESTIS LUX MUNDI, Available online: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/motu_proprio/documents/papa-francesco-motu-proprio-20190507_vos-estis-lux-mundi.html (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Wilson, Debra Rose. 2010. Health Consequences of Childhood Sexual Abuse. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 46: 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yallop, David. 2010. Beyond Belief: The Catholic Church and the Child Abuse Scandal. London: Constable. [Google Scholar]

- Yocum, Sandra. 2013. The Priest and Catholic Culture as Symbolic System of Purity. In Clergy Sexual Abuse: Social Science Perspectives. Edited by Claire M. Renzetti and Sandra Yocum. Boston: Northeastern University Press, pp. 90–117. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Weger, S.E. Unchaste Celibates: Clergy Sexual Misconduct against Adults—Expressions, Definitions, and Harms. Religions 2022, 13, 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050393

de Weger SE. Unchaste Celibates: Clergy Sexual Misconduct against Adults—Expressions, Definitions, and Harms. Religions. 2022; 13(5):393. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050393

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Weger, Stephen Edward. 2022. "Unchaste Celibates: Clergy Sexual Misconduct against Adults—Expressions, Definitions, and Harms" Religions 13, no. 5: 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050393

APA Stylede Weger, S. E. (2022). Unchaste Celibates: Clergy Sexual Misconduct against Adults—Expressions, Definitions, and Harms. Religions, 13(5), 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050393