1. Introduction

A brief commentary on the title of this essay is the most efficient way to introduce its objective. The aim is to explore (1) the ways in which manuscript technologies and paratextual features extend ancient theories about memory retention to texts and (2) how such manuscript techniques enable new capacities for creatively reshuffling textual information, capacities that, in turn, (3) produce new intellectual possibilities for theological expression. In other words, my interest is in how transferring certain mnemonic techniques to textual artefacts (especially in the form of numerically ordered textual divisions for citation and cross-reference) opens up new possibilities for creatively reorganizing or synthesizing textual information for theological ends. So: The integration of memory arts, manuscript arts, and theological development.

Now: To clarify some key terms. By “art of memory” (

ars memoriae) I refer to the techniques (or “mnemotechnics”) described by ancient intellectuals as early as Aristotle for more effectively organizing and recalling various types of information.

1 The most influential ancient sources reflecting on such intellective technologies are the anonymous treatise

Rhetorica ad Herennium (Book 3), Cicero’s

De Oratore (Book 2), and Quintilian’s

Institutio Oratoria (Book 11). All three treatises were written within the first centuries BCE and CE, but many others would follow.

2 Reflection on matters of memory and

artes/τέχναι for augmenting faculties of recollection especially proliferated in medieval literature (see esp.

Carruthers 1998, [1990] 2008;

Carruthers and Ziolkowski 2002). But interest in human memory, its whims, and its enhancement persists today. When it comes to enhancement in particular, the techniques recommended by our ancient theorists have proven remarkably durable, though they are now more often happened upon in popular self-help literature. The intriguing relation of memory and external technologies—be they paratextual ordering systems, digital search engines, or even fonts—also persists.

One of the most important external technologies for aiding the storage of textual knowledge are “manuscript technologies.” I say

external technologies for storing knowledge because they employ the principles memory theorists recommend for the human mind but transfer them to texts. These are editorial adornments to manuscripts, often independent of authorial approval, and intended to augment the readerly experience. Such technologies range from filing systems (such as those organized by titles), to framing devices (such as prologues and concluding summaries, or other internal titular material), to any type of internal editorial supplements (such as book, chapter, and verse divisions or page numbers).

3 When it comes to ancient evidence, these paratextual features are usually added by later editors. This is certainly the case when it comes to what modern readers experience in printed Bibles.

Interest in paratextual technologies has grown apace in twenty-first century scholarship.

4 The “Titles of the New Testament” project (TiNT) is one especially important contribution to this neglected material that often so powerfully frames and controls readerly experiences (See esp.

Allen and Rodenbiker 2020;

Coogan 2021b;

Coogan 2017;

Lang and Crawford 2017;

Lincicum 2015;

Crawford 2015;

Gathercole 2013). The power of this technology is perhaps nowhere more pervasive than in the case of sacred literature. To think more systematically about this threefold entwining of cognitive aids, manuscript tools, and theological abstraction, the essay unfolds in three parts, all of which are intertwined.

First, I explore in greater detail the ancient interest in “arts of memory” and some of the specific proposals for how various forms of ars might aid memoria. The specific interest is in the techniques these ancient authors recommend for recollecting and reorganizing information, especially textual information. These techniques for recollection were usually in service of rhetorical ends. As Quintilian understood, when it comes to rhetorical contestation, the best trained memory “is improved by cultivation.” When it comes to besting an opponent’s argument in the arena of rhetoric, this requires “the power of the mind” to fully usurp the opposition’s case, strategically “rearranging it as is most advantageous” for refuting it (Institutio Oratoria 11.2.1–3). Techniques that might enhance one’s mnemonic capacity and tactical dexterity are, therefore, highly desirable for any rhetor.

I next look at a specific case where the methods for improving memory recommended by ancient memory theorists are transferred from the human mind to a literary corpus. This is Priscillian of Avila’s fourth-century CE

Canones Epistularum Pauli Apostoli and his accompanying Latin edition of the Pauline letters. Key to Priscillian’s work are his editorial additions to Paul’s letters, which include an innovative paratextual numbering scheme and cross-referencing system. Priscillian’s technology links the letters to the

Canones and the

Canones to the variously divided sections of the letters in something of a hypertextual relationship. Priscillian’s paratextual division of the Pauline corpus is the engine of the total project. If titles assigned to the Pauline letters assist discussion and comparison of documents in terms of their total contents, Priscillian’s numerical scheme, which is analogous to modern versification in its precision, enabled the abstraction and reorganization of single sentences from across the Pauline corpus.

5 As ancient memory theorists well understood, technologies for dividing and sequentially ordering information has powerful mnemonic potential (in modern cognitive psychology, this is termed “chunking”). To apply such technologies to textual information is Priscillian’s innovative transference of these “memory arts” to “textual arts.”

I conclude by reflecting on the larger intellectual implications of paratextual schemes for ordering textual knowledge, and particularly how processes of textual abstraction and reorganization generate intellectual abstraction—that is, how paratextual cross-referencing systems provide recall mechanisms to rearrange and present new intellectual “wholes” out of particular textual “parts.” This is where technology and theology meet, and in ways often undertheorized, ways especially significant for questions of how one might read an anthology like the New Testament.

2. Textual Division and Ancient Arts of Memory

The story of titles, chapters, paragraphs, verses, indices, and other supplementary adornments to texts is a long one.

6 At every step of development, it is also one with complementary intellectual implications for processing and presenting textual information. The earliest theorists of memory understood this intimate relation of τέχνη/

ars and μνήμη/

memoria. Ancient texts conventionally termed “classical” (such as Homer, the playwrights, and also the earliest biblical traditions) did not make use of paratextual division systems for conceiving or presenting their works. Book divisions, and eventually sometimes chapter divisions, were added by later editors. The earliest evidence for this is around the first century BCE, and so centuries after their initial composition (

Higbie 2010). By the first century CE, however, it was common for authors to structure lengthy works according to principles of book division. This, in turn, allowed for more flexible interaction with the contents of these works. Pliny the Elder’s (first century CE) sprawling thirty-seven-book

Natural History is a far more manageable document thanks to the principle of book division and the table of contents (along with editorial commentary) that comprises most of Book 1.

7 By the fourth century CE, compositional principles and readerly aids such as “titles” (τίτλοι;

tituli), “books” (βίβλοι;

libri), and “chapters” (κεφάλαια;

capitula) were widely known and continued to create new possibilities for textual reference and interpretation.

Other major changes in manuscript technologies around the first few centuries of the common era also had profound implications for conceiving the shape of texts and the possibilities for interacting with them. Most significant was the technological conversion from the scroll to the codex.

8 As is now well documented, Christians were the vanguard of this media revolution and remained the most advanced entrepreneurs of book technology in the Roman world (See esp.

Hurtado 2006;

Grafton and Williams 2006;

Gamble 1995, pp. 42–81). As classicists König and Whitmarsh note, this should be no surprise: “It is surely no coincidence that the earliest codices contained Christian and technical material, two genres of discourse that privilege, indeed insist upon, cross-referencing and non-linear reading” (

König and Whitmarsh 2007, p. 34) Ancient memory theorists also appreciated the intellectual power of mnemonic systems that would aid random-access recollection of dense amounts of information stored in simple symbolic units. Although their concern was in “memory information,” the principles they developed were easily extended to “textual information.” And for a text like the Bible, numbers proved to be the key to organizing textual knowledge. The simplicity and efficiency of the chapter and verse “chunking” system has, since its earliest entrepreneurs, proven a remarkable contribution to Christian reading cultures. A reference to Isaiah 53, for instance, is an easy way of recalling a larger body of stored information related to the so-called “suffering servant.” A reference to Isa 53:7, however, isolates far more specific information for, perhaps, far more specific purposes. A reference to John 3 likely provokes recollection of Jesus’ night-time rendezvous with Nicodemus. A reference to John 3:16, however, aids in recalling the information stored in a single sentence, and a sentence easily abstracted from its narrative context for more systematic purposes. The verse system thus facilitates easy comparison with other similar theological abstractions related to God’s love for the world, the giving of God’s son, human belief, or eternal life. The utility of

mental storage systems for assembling and recalling textual data is precisely what ancient memory theorists appreciated in terms of organizing the mind. What they did not realize was the potential for

paratextual management technologies to revolutionize the relation of human thought and textual knowledge.

Aristotle is perhaps the earliest ancient theorist of memory. In On Memory and Recollection, Aristotle identifies one of the key principles for augmenting memory: A storage system indexed by simple symbols. The symbolic simplicity provided by the twenty-four letter Greek alphabet was Aristotle’s recommended apparatus for amassing complex data in symbolic structures in order to access the stored data in creative ways. He discusses this under the rubric of “recollection” (ἀνάμνησις). He notes that attempts at recollection begin at some “starting point” (ἀρχή) and usually then proceed to the matter being sought “following a chain of succession” (αἱ κινήσεις ἀλλήλαις). Because recollection usually involves this process of rummaging through the mind in pursuit of a particular bit of stored information, it is most efficient for one’s mental system to have a clear principle of storage with an “orderly arrangement.” This would allow a thinker either to happen immediately upon the stored information or at least begin a recollection process as near to what is sought in the mind as possible. It would also allow one to range more efficiently and creatively across the surrounding information, moving forwards and backwards, even recombining bits of stored information and their relation to each other.

Aristotle’s proposal is known today as the “loci method” of memory (or “locational memory”). As he describes it:

This is why some people seem, in recollecting, to proceed from

loci (ἀπὸ τόπων)…. For instance, suppose one were thinking of a series, which may be represented by the letters ABCDEFGH;

9 if one does not recall what is wanted at A, yet one does at Ε; for from that point it is possible to travel in either direction, that is either towards D or towards F. If one does not want one of these, he will remember by passing on to F, if he wants G or H. If not, he passes on to D. Success is always achieved in this way. The reason why we sometimes recollect and sometimes do not, although starting from the same point, is that it is possible to travel from the same starting-point to more than one destination; for instance from C we may go direct to F or only to D.

10

This is essentially an intellective technology for streamlining memory function. The system is powerful for getting one’s memory quickly to the information held in θ via ΔΕΖH, but it is also powerful insofar it enables a more orderly ability to think the information in Δ and θ together, irrespective of ΕΖH, if one should so choose. The aim is to make the mind a well-ordered filing system with easy access to all that is stored in it. The creative power of the system is the potential for random (or non-linear) recombination of stored bits, as in the example of what is stored in Δ and what is stored in θ.

By the first century BCE, the

loci method of memory recall had become mainstream. Book 3 of the

Rhetorica ad Herennium is still among the most influential representatives of it from this time period. The concern in this treatise, as with others after it, is how to harness mental powers for the ends of rhetorical finesse. The treatise defines the improved mental technique of recollecting information “from

loci” (

ex locis) as “artificial memory”

11 (or, certainly better, “technical memory”) (

artificiosa memoria) (3.16.29). This is memory enhanced by acquired techniques not necessarily native to ordinary brain functioning. Much like Aristotle centuries prior, the author explores the mnemonic power of sequentially ordered

loci. The alphabet is again the recommended symbolic heuristic for storing sequentially ordered data:

Those who know the letters of the alphabet can thereby write out what is dictated to them and read aloud what they have written. Likewise, those who have learned mnemonics (

mnemonica) can set in

loci what they have heard, and from these deliver it by memory…. We should therefore, if we desire to memorize a large number of items, equip ourselves with a large number of

loci, so that in these we may set a large number of images. I likewise think it obligatory to have these

loci in a series, so that we may never by confusion in their order be prevented from following the images—proceeding from any

loci we wish, whatsoever its place in the series, and whether we go forwards or backwards—nor from delivering orally what has been committed to the

loci.

12

The treatise also appreciates the importance of an ordered series of stored information for entering mental data at random access points and moving around in the data in multiple directions: “So with respect to the loci. If these have been arranged in order, the result will be that, reminded by the images, we can repeat orally what we have committed to the loci, proceeding in either direction from any loci we please. That is why it also seems best to arrange the loci in a series” (3.18.30–31). The treatise goes on to recommend other strategies for arranging the loci visually for maximal mnemonic effect, such as markers for grouping them in sets of five (3.17.31). This obviously anticipates paratextual division systems, which will translate technologies adapted for the mind to the manuscript.

Some decades after Rhetorica ad Herennium, Cicero further develops the importance of memory schemes from rhetorical purposes in his De Oratore. He, too, understood that “the best aid to clearness of memory consists in orderly arrangement” (2.86.354). He also understood the utility of an ordered loci infrastructure system and had additional thoughts on the optimal way of visualizing such a mental system: “[O]ne must employ a large number of loci which must be clear and defined and at moderate intervals apart, and images that are effective and sharply outlined and distinctive, with the capacity of encountering and speedily penetrating the mind” (2.82.358). It is, however, Quintilian, in the first century CE, who provides the most developed account of the loci scheme for committing textual material to memory.

Quintilian likens the storage and arrangement of

loci to “a large house divided into many separate rooms” (

Institutio Oratoria 11.2.18).

13 Chunks of text are stored in the various rooms. The key to organizing this mental space is, as with Aristotle, a sequentially ordered sign system. For memorizing written material in particular, Quintilian emphasizes the importance of “division and composition” (

divisio et compositio) (11.2.36), two principles that prove vital for later memory theorists and, indeed, entrepreneurs of manuscript technologies.

Divisio is the partitioning of a text into discrete parts. In a macro sense, for an anthology like the Bible, this occurs even at the level of book titles. But for purposes of mnemonic power, more precision is needed. Quintilian recommends the following:

If a longish speech has to be held in the memory, it will be best to learn it section by section (

partes) (memory suffers most by being overburdened), but these sections should not be too small, or there will be a lot of them, and they will distract and fragment the memory. I do not want to lay down a definite length, but, if possible, the sections should coincide with the ends of topics, unless a topic is so complex that it needs to be subdivided.

14

With a text so divided into units, compositio becomes possible, which is the ordering of the data in one’s mind (“first, second, and so on” [11.2.37]). With the data committed to memory in this sequentially ordered way, one has the mnemonic facility to roam freely within the “mind’s eye” (11.2.32) and enter a text at any given part, wandering forwards and backwards, or even skipping ahead or behind. A text divided and mentally stored in information-rich ordered chunks also allows for creative recombination, comparison, and collation—as in a filing system. Disconnected parts are thus more easily related to each other for interpretively generative purposes.

It is important to note that for Quintilian and the memory theorists prior to him, the schematic division and arrangement of information (including textual information) for memory purposes is something organized within one’s own mind. The proposition of information-dense symbolic units is a heuristic for the human brain.

Divisio et compositio occurs in structures of thought. The “arts of memory” thus do not necessarily involve “editorial arts” related to textual artefacts. Quintilian and his predecessors are

memory technologists. They are not entrepreneurs in the domains of scroll or codex machinery, and so they give no thought to the intellectual possibilities of extending their mnemonic principles to the organization of

textual knowledge (

König and Whitmarsh 2007). For this sort of innovation, I turn to Priscillian of Avila’s fourth-century CE paratextual invention.

15 3. Ancient Manuscript Technologies: Priscillian’s Canones Epistularum Pauli Apostoli

Whether he knew it or not, Priscillian harnessed the power of mnemonic principles for manuscript purposes, producing one of the most sophisticated and powerful numerical cross-refencing system in the ancient world.

16 The transference of memory techniques to manuscript technologies would be well appreciated in medieval thought. In her now classic work on memory, Mary Carruthers explores at length the effectiveness of textual divisions as mnemonic aids. In examining the innovative schemes developed by Christians for memorizing biblical texts, Carruthers notes: “The crucial task for recollection is the construction of the orderly grid through which one can bring to mind specific pieces of text…. [This] enables one to construct mentally a concordance of the text, thus disputing quickly and surely, making citations to authorial texts by number alone” (

Carruthers [1990] 2008, p. 102). Priscillian is among the most neglected pioneers of this numerical sorting system for textual knowledge.

17 The sophistication of his collation of Pauline data through

divisio et compositio also indicates a mind that had become a concordance of Pauline words and information.

Priscillian’s biography need not be rehearsed again at great length: Former Spanish bishop; executed for heresy (among other things) in the 380s (even though his

Canones where designed to battle heretics with Pauline artillery); author of numerous theological tractates only recently discovered;

18 and, of course, pioneering entrepreneur of paratextual manuscript tools.

19 His

Canones Epistularum Pauli Apostoli is his enduring contribution to paratextual arts. The work is preserved in Vulgate manuscripts in three parts.

20 The first part, framing the work, comprises two prologues. The first prologue, by one Bishop Peregrinus, distances the work from Jerome, maintaining that although it is the handiwork of Priscillian (a known heretic) it has been sufficiently purged of error. It is included because “there were still many extremely useful things” in it.

21 The second prologue is Prisciallian’s own. It explains the reason for the work and then supplies a very practical “users guide” for the cross-referencing technology.

22 The second part of the work is the

Canones. These are ninety (XC) abstract syntheses of Pauline ideas expressed in propositional form.

23 Canon I is representative of what follows:

| Can. I. Deus verax est, spiritus quoque deus et deus saeculorum possidens inmortalitatem estque invisibilis lucem habitans inaccessibilem, rex etiam atque dominus, cuius est imago ac primogenitus Christus, in quo non invenitur ‘est et non, sed est’ tantummodo. | Canon 1. God is true, and God is also Spirit and God of the ages, possessing immortality and is invisible, dwelling in inaccessible light, King and also Lord, whose image and firstborn is Christ, in whom “yes and no” is not found but “yes” alone. |

| Rom. 18. | Rom. 3:1-4 |

| Cor. II. 6. 18. 22. | 2 Cor. 1:18-20; 3:17-17[ubi]; 4:2[ad. om. cons.]-4:4[qui est] |

| Col. 5. | Col. 1:15-16 |

| Tim. I. 5. (11.) 28. 29. | 1 Tim 1:12-16; 2:8-10; 6:6-12; 6:13-16 |

| Titus 1. | Titus 1:1-4 |

| Hebr. 1. 11. 18. 19. | Hebr. 1:1-4; 6:11-7:17; 10:19-34; 10:35-11:35[mort. suos]24 |

The propositions organize the information contained in the lists of citations underlying each Canon. The titles and integers thus compress the relevant data. Removed from their local Pauline contexts, the citations are abstracted and recombined in relation to each other for the purposes of dogmatic synthesis. The engine of the synthesis is the final facet of the total apparatus: Priscillian’s edition of the Pauline corpus, which precisely divides the letters into numerically ordered units for recombination in support of the various dogmatic Canones.

In terms of scale, Romans in Priscillian’s edition has 125

testimonia (which is his word for what English speakers mean by “verses”).

25 Modern bibles break Romans up into sixteen chapters and around 430 verses, depending on a few text-critical decisions. Modern versification thus allows for far more precision in citation, but Priscillian’s 125

testimonia certainly enable far more precision than simple title reference (“as Paul says to the church in Rome”) or the 16-chapter system alone, which preceded Robert Stephanus’ 1551 versification of our modern bibles. With Priscillian’s division system, he is able to cite portions of Romans in 66 of the 90

Canones and 243 times in total. Priscillian’s normal practice is to divide Paul’s letters into chunks approximately the size of two to four of our modern verses, give or take.

26 Priscillian’s

Ad Romanos I, for instance, corresponds to the modern Romans 1:1-4, ending at

secundum. Priscillian’s

Ad Romanos II corresponds to Romans 1:4, beginning at

secundum, and ending at the

quia of Romans 1:8. These divisions usually represent recognizable sense units or places where a clear shift in subject is observable. often Priscillian seems to have associated his

testimonia with key words, another mnemonic tool. When one gets inside the

Canones and work through their logic, it appears as though, in his labor of dividing the Pauline corpus into nearly 600 discrete

testimonia, Priscillian’s mind had indeed become a lexicon of Pauline data. In many cases, his collation of key words under the subject of a

Canon is exhaustive. Whether or not Priscillian intended at the outset of this project to rely so heavily on lexical cross referencing is impossible to know, but what he appears to have learned well from his detailed approach to textual division is the tremendous mnemonic power of a numerical grid. Here is the raw data:

| Pauline Letter | Number of Testimonia (“verses”) | Number of times the letter is cited | Number of Canons in which the letter appears |

| Romans | 125 | 243 | 66 |

| 1 Corinthians | 105 | 184 | 57 |

| 2 Corinthians | 61 | 105 | 44 |

| Galatians | 38 | 72 | 27 |

| Ephesians | 41 | 96 | 45 |

| Philippians | 25 | 43 | 26 |

| 1 Thessalonians | 22 | 45 | 26 |

| 2 Thessalonians | 10 | 21 | 14 |

| Colossians27 | 34 | 74 | 43 |

| 1 Timothy | 31 | 62 | 32 |

| 2 Timothy | 26 | 49 | 25 |

| Titus | 15 | 26 | 17 |

| Philemon | 5 | 6 | 5 |

| Hebrews | 28 | 112 | 52 |

| Total | 566 | 1138 | |

Now: to the system itself. The cross-referencing relationship between the dogmatic propositions of the

Canones and the versified Pauline data involves two colors of ink. Priscillian numbers the

testamonia in each Pauline letter, from beginning to end, in black ink. The dogmatic

Canones are numbered one (I) to ninety (XC) in red ink.

28 The number of the various

Canones are integrated within the Pauline edition wherever particular

testamonia are cited in support of any of the ninety dogmatic syntheses. This allows for the overlapping, integrated numbering system. Readers can range from any of ninety dogmatic

Canones (ordered in red numbers) to any of the Pauline

testamonia that inform the

Canones groupings. Or readers can range from a given Pauline letter and its numbered

testamonia (ordered in black ink) to the particular dogmatic

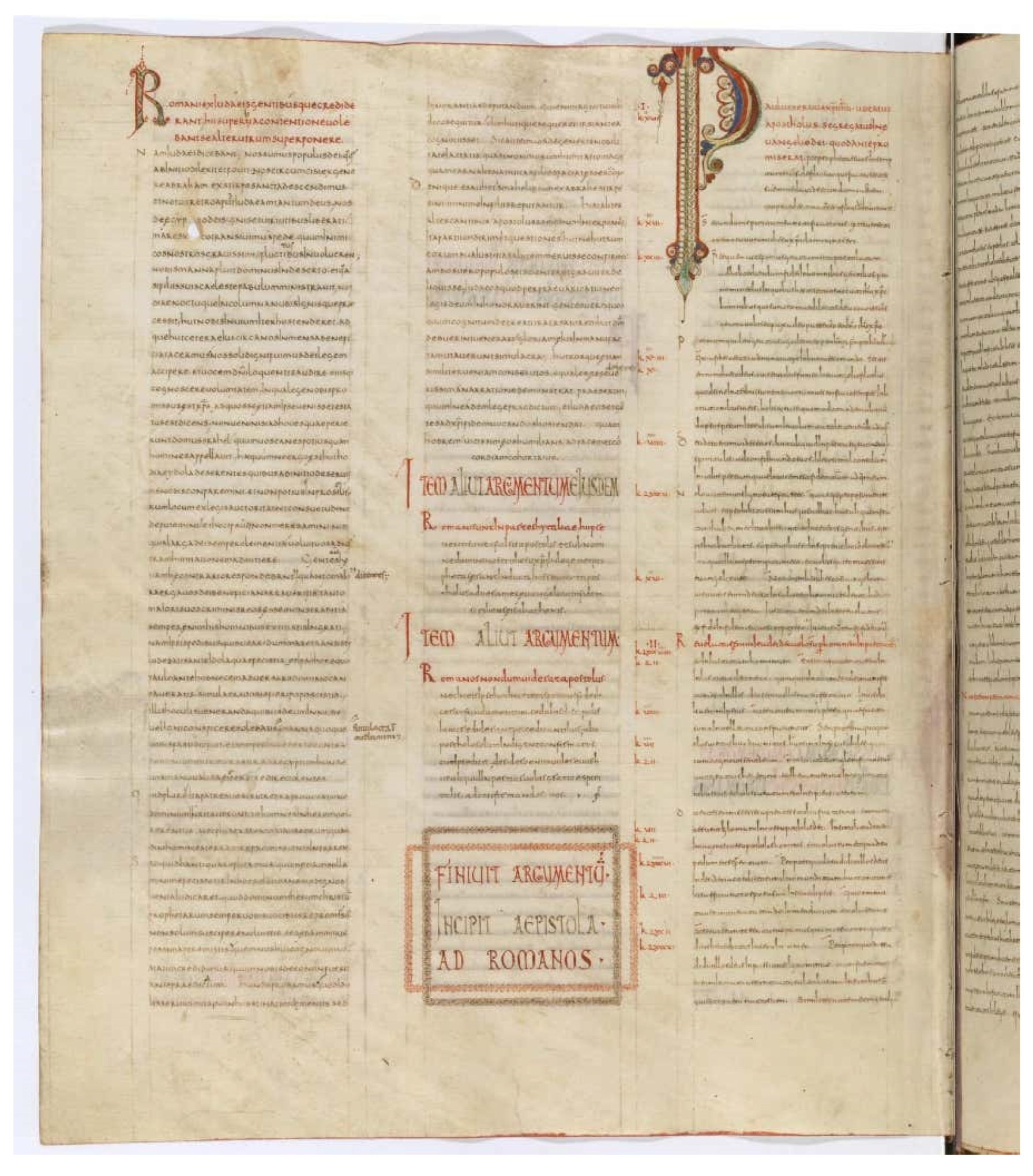

Canones where it is marshalled for support. Codex Cavensis, fol. 255v. exhibits the paratextual principles of Priscillian’s numbering scheme (

Figure 1).

29 The text of Romans begins in the third column. The 125 divisions (

testamonia) are ordered in the left-hand margin of the text: I, II, III, and so on in black ink. Where one of the “verses” appears in any of the ninety

Canones, this is listed in red ink, beneath the

testamonia number. Codex Cavensis, fol. 253r. preserves Priscillian’s dogmatic

Canones with the supporting Pauline prooftexts beneath each proposition (

Figure 2).

30 An example is best to appreciate the hermeneutical potential of this cross-referencing paratextual technology, and so I turn to

Canon 79. There is nothing especially outstanding about this example, and there are certainly more theologically interesting moments in the work, but

Canon 79 clearly demonstrates the rich theological integration that the use of simple integers enables. It also displays how Priscillian’s own mental index, combined with the technology of a numerically divided Pauline corpus, align for creative theological purposes.

| Can. LXXIX. Quia ob peccatorum immensitatem scelesti homines deterioribus traduntur passionibus et quia non sponte creatura subiecta sit et a Christi caritate neque alia creatura no separet et euangelium creaturae sit praedicatum. | Canon 79. That wicked people are handed over to worse passions because of the enormity of their sins, and that creation has not been subjected voluntarily, and no other creation separates us from the love of Christ, and the gospel was preached to creation.31 |

Rom 9. 61. 62. 63. 68. 100.

Col 5. 9.

I Tim 15.

Hebr 18. | Rom 1:24-27[operantes]; 8:19-20; 8:21; 8:22-24[sumus]); 8:34[Christus]-39); 13:8[qui?]-13:11[surgere])

Col 1:15-16; 1:23[quod praedic.]-25

1 Tim 4:1-3[fidelibus]

Heb 10:19-34 |

Since Priscillian always lists his citations in order from Romans through to Hebrews, it is not always obvious how all the citations tie together in relation to the canonical proposition until each has been explored. Even then, it remains the work of the reader to make hermeneutical decisions about how to relate them. So, although Priscillian controls the dogmatic proposition and the selection of prooftexts to support it, users of the work still have creative responsibility. In the case of Canon 79, the key theme weaving together Priscillian’s collation of texts is “creation” (creatura). The best place to begin in this case is where Priscillian does, with Rom 1:24–27 (and in what follows, I keep to the modern citation system). With the citation of Rom 1:24–27, Priscillian establishes the plight with which the heading Canon begins. Humanity, and indeed creation itself, has been handed over to imprisonment under base passions. As Paul explains in Rom 1:25, this handing over has come about because of humanity’s grave error in worshiping creation rather than the Creator: “They exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshiped and served the creature instead of the creator (creaturae potius quam creatori).” But Priscillian immediately reframes this plight by citing the only other subsequent occurrences of creatura in the whole of the letter, which is Rom 8:19–39. The word here appears an additional five times, in rapid succession, and at the beginning and end of this stretch of verses.

For the creation (creaturae) waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God; for the creation (creatura) was subjected to futility, not of its own will but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself (ipsa creatura) will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. We know that the whole creation (omnis creatura) has been groaning in labor pains until now…For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation (creatura alia), will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord. (NRSV)

This collation of creatura references, and the juxtaposition of Romans 1 and Romans 8, supplies the textual evidence, and the very terminology, for all four clauses in Canon 79. But there is more. The reference to the divine love for creation in Rom 8:34–39 also leads Priscillian to Rom 13:8–11, where Paul explains the necessity of neighborly love and its function in fulfilling the law. The point of coupling these texts is presumably to emphasize that the vertically ordered love of God that embraces and restores humanity is also to be horizontally extended among humanity. This, too, is how the gospel should be preached to every creature.

The key word creatura also leads Priscillian outside of Romans and next to the Colossians citations, where Christ is identified as “the first-born of all creation” (primogenitus omnis creaturae), and the one through whom all things “were created” (creata sunt). Here again is the Christ–creature vertical orientation. But then there is the statement in Col 1:23 that the gospel has been proclaimed “to every creature under heaven” (in universa creatura, quae sub caelo est), which reemphasizes the horizontal extension of good news to all creatures. This text is also the most direct evidence for the final proposition in the Canon. Again, the subjection of creation to its own passions and sins is not without hope. Christ, the first-born of all creation, brings gospel to it and cannot be separated from it.

The theme of creation next directs Priscillian to 1 Tim 4:1–3, where Paul laments the appearance of latter-day apostates with “seared consciences” (cauteriatam… conscientiam). Presumably the verb “created” (creavit) in 4:3 is what links these verses with the prior texts. Given that the aim of the work is to provide a tool for correcting heretics, it is unsurprising that Priscillian turns to a passage that connects deviant views about created realities. The principal error of these “heretics,” according to 4:3, is forbidding certain creaturely pleasures, such as marriage and foods. In so doing, those in error refuse things “which God created (creavit) to be received with thanksgiving by those who believe and know the truth” (4:3). With the inclusion of this passage Priscillian thus sits these latter-day “heretics” alongside the handed over humanity characterized in Romans 1. But notice the interesting difference. In contrast to those who serve the creature rather than the Creator (see Rom 1:25), those at fault here commit the opposite error. They do not receive God’s creation as a good to be enjoyed.

How Priscillian gets to the citation of Heb 10:19-34 is less obvious.

32 The linkage probably comes via the reference to

conscientia in 1 Tim 4:2, and so the key reference in this large chunk of Hebrews is the statement about having “hearts sprinkled clean from an evil conscience” (

conscientia mala) in 10:22. This Hebrews

testimonium, therefore, supplies the antidote to those with seared consciences who harbor contempt for God’s creation. The antidote to this is Christian baptism—“bodies washed with pure water” (

abluti corpus aqua munda). This is a cleansing of the intellect that undoes the consequences of a disordered relationship with good creaturely gifts. Therefore, just as the abandoned creatures of Rom 1:25 are not without the hope of redemption in Romans 8, so those with “seared consciences” in 1 Timothy have the hope of a repaired conscience in Heb 10:22.

The main point of this brief tour of Canon 79 is this: A compelling and ever open-ended Pauline theology of creation is here embedded in a concise list of otherwise arbitrary titles and integers:

Rom 9. 61. 62. 63. 68. 100.

Col 5. 9.

I Tim 15.

Heb 18.

By conjoining the titles of Paul’s letters with a numerical code, Priscillian encrypts dense assemblages of textual knowledge. This knowledge is certainly focused, in specific ways, by the dogmatic propositions, but the density of information stored in the integers opens up vast potentialities for meaning within and beyond the dogmatic directives. As ciphers of Pauline data, the integers direct the reader to texts. As the texts are explored, and as text turns to text and back again, differently illuminating one another and the ensemble as a whole, the potential for a total Pauline theology of creation is there for readers to develop in theologically generative ways—and, of course, to address heretics, in accordance with Priscillian’s wishes. The reader who takes the time to explore Priscillian’s Canones closely, and with the “skillful zeal” he asks for in his prologue, will find that Priscillian emerges as much more than a collator of data. By harnessing divisio et compositio with the ordering scheme of integers applied to manuscripts, Priscillian anticipates the technologies of modern biblical citation for constructive theological purposes by over 1000 years.