1. Introduction

In an age where mental health concerns are ever-increasing, healing practices and places are needed. In 2018, the Mental Health Foundation commissioned a UK-wide stress survey with 4619 people and found that 74% of adults have at some point over the past year felt “so stressed” that they “felt overwhelmed” or “unable to cope”, and the survey also found that 32% had experienced “suicidal thoughts” or “feelings because of stress” (

Mental Health Foundation 2021b). Since 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has placed both the physical and mental health of people under an increased amount of stress. In a survey from June 2020, 13% of adults reported “new or increased substance use due to coronavirus-related stress”, and 11% of adults reported “thoughts of suicide in the past 30 days” (

Panchal et al. 2021). Bereavement, isolation, loss of income, and fear are triggering mental health conditions, or the deterioration of existing conditions, such as insomnia, anxiety, and depression (

WHO 2020). As a result, an increasing number of people are turning towards spirituality, such as Buddhist mindfulness practice and Buddhist centers, for support. It is timely, therefore, to reflect upon what ancient Buddhist wisdom and Buddhist contemplative space can offer to beings as an enduring source of wellbeing, and to explore how this is manifest in contemporary life.

As a traditional spiritual practice, mindfulness offers an approach to alleviate stress and restore inner peace and tranquility for people. In 2018, a study suggested that 15% of the adult population of Britain had learned to practice mindfulness by using an app, reading a book, or attending a course (

Simonsson et al. 2020). It has also been incorporated into a treatment therapy (mindfulness-based cognitive therapy), recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as a way to prevent depression in people who have had three or more episodes of depression in the past (

NICE 2009), as well as the self-help support for mental health recommended by the National Health Services (NHS) to improve mental health (

NHS 2018). As notable evidence, Headspace, the mindfulness meditation app, has experienced a doubling of downloads of the app since mid-March 2020, “14-fold increase in users completing a free guided meditation for relieving stress; 110% increase in the usage of a “buddy” support; and 70% increase in free live group meditation starting-out sessions”, which represents recognition of the benefit that mindfulness can bring (

Antonova et al. 2021). The prevalence of secular online mindfulness training brings us to question the role of Buddhist spaces when learning or practicing mindfulness; if mindfulness can be learned and practiced via an online app, what is the role of physical place in general, and contemplative space in the Buddhist context in particular? What are the characteristics of Buddhist contemplative space, and how can they support wellbeing in contemporary urban life and settings?

Some argue that mindfulness as a spiritual activity can be practiced anywhere and anytime (

Kabat-Zinn 2013b); however, the role and influence of the physical environment is worthy of attention. There has been a long history of dedicating places to contemplative and spiritual purposes, such as temples and retreat centers. Historic and contemporary settings have been established with the intention of introducing a moment of calmness to people’s lives, or potentially to connect us with something transcendent. As embodied beings, we experience physical space and modify it in response to such experiences, both contemplative and profane. As the famous statement by Winston Churchill articulates, “We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us” (

Bernheimer 2017). The importance of such intentionally designed contemplative spaces, both indoors (buildings) and outdoors (gardens and whole landscapes), has arguably gained more relevance in this turbulent day and age as people are facing more rapid changes than before.

Hence, this paper aims to explore the potential relationship between the formal mindfulness practice and the Buddhist contemplative space where it is taught and practiced, and to investigate how contemplative space may influence and facilitate mindfulness as a spiritual activity. In the following section, we review literature from Buddhist doctrines to define mindfulness, Buddhist contemplative space, and to summarize the key characteristics of places ideal for mindfulness practice. Next, we present a case study of Kagyu Samye Dzong, a Buddhist center in central London, followed by discussion of survey and interview results, and conclusion.

This section examines (1) the key definitions and meanings of Buddhist mindfulness from different sources of literature. There are examples of mindfulness practice rooted in other religions, for example, Hinduism, Judaism, and Christianity (

Trousselard et al. 2014), which are not to be denied. Nonetheless, contemporary mindfulness popularized in the West mostly derives from a Buddhist tradition (

Husgafvel 2016;

Monteiro et al. 2014). We also (2) identify the typical qualities of places where formal mindfulness practice takes place, i.e., the physical space(s) where mindfulness meditation is conducted.

1.1. Definition of Mindfulness

In the original Buddhist text

Satipatthana Sutta, mindfulness is “to be alert to what one is doing in the present; to recognize the skillful and unskillful qualities that arise in the mind; and also how to effectively abandon the qualities that get in the way of concentration” (

MN10 1994). In other words, mindfulness means not forgetting a known object in the past, and the mind not being distracted (

Mipham and Kunsang 1997). Modern Buddhist teacher Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche (

Trungpa and Gimian 2008) said that “mindfulness does not mean pushing oneself toward something or hanging on to something. It means allowing oneself to be there in the very moment of what is happening in the living process - and then letting go.”

Nhat Hanh Thich (

2009) similarly defines mindfulness as that which “shows us what is happening in our bodies, our emotions, our minds, and in the world. Through mindfulness, we avoid harming ourselves and others.” In short, Buddhist mindfulness refers to the process which one is fully aware of in the very moment of the living process (

MN10 1994) with an ardent, alert, and watchful mind (

DN22 2000;

Shonin et al. 2014), as well as not forgetting the known object (

Mipham 1997), for example, to remember and incorporate the awareness that can give rise to the pervasive and enduring feeling of calm and spiritual wellness. In Buddhism, chaos, confusion, and suffering arise due to distractions and forgetting our true nature (

Mingyur and Swanson 2009;

Trungpa and Lief 2009), for which, mindfulness is a way to bring back the lost awareness which has already caused so many problems. While striving for the ultimate goal of attaining enlightenment is at the heart of Buddhism, this process can result in the more everyday benefit of gaining calm, serenity, moments of inner peace, and improving one’s wellbeing.

1.2. Secular and Buddhist Mindfulness Practices

From these Buddhist roots, contemporary secular mindfulness arose to accommodate practitioners of different religions or none at all. Jon Kabat-Zinn, who adapted the Buddhist teachings on mindfulness and developed the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program (MBSR), defined mindfulness as an “awareness, cultivated by paying attention in a sustained and particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally” (

Kabat-Zinn 2013a,

2013b,

2019). The original purpose of MBSR, and subsequent types of secular mindfulness, was to discover whether mindfulness and relaxation exercises could help people with chronic health problems such as high blood pressure, chronic pain, and anxiety disorders (

Mikolasek et al. 2017;

Kabat-Zinn et al. 1985). It is an option for those seeking calmness and inner peace without taking a religious path (

Stahl et al. 2019).

Mindfulness can be cultivated through both formal and informal mindfulness practice. Despite the range of definitions of formal and informal practice, formal mindfulness practice can be considered “to take place when practitioners specifically set aside time to engage in mindfulness meditation practices such as the body scan, sitting meditation, and mindful movement” (

Birtwell et al. 2018). Informal mindfulness practice can be done by “weaving mindfulness into existing routines” and everyday activities such as mindful eating, drinking, chewing, or mindfully washing the dishes, or silence (

Birtwell et al. 2018;

Shonin et al. 2015). However, both aim toward awakening to karma, emptiness, and non-self, which is a major factor in Buddhist training (

Shonin et al. 2015).

In general understanding, mindfulness is a contemplative exercise that can take place in many locations, allowing people of different age groups, gender, and cultural background to experience the effect of mindfulness practice (

Mental Health Foundation 2021a). It is an effective way to significantly reduce the effect of stress, anxiety, and related problems from the mind-body approach (

Mental Health Foundation 2016) and mitigating and alleviating suffering associated with chronic illnesses (

Niazi and Niazi 2011). There is growing evidence to show that mindfulness meditation helps achieve a better state of physical health and mental health (

Alda et al. 2016;

Malinowski et al. 2017;

Behan 2020) and is able to be applied to clinical psychology, and other general fields as a support (

Niazi and Niazi 2011). With the recent COVID-19 pandemic, an increasing amount of empirical evidence shows that the generation of mindfulness has a positive impact on people’s physical and mental wellbeing, resulting in fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety from participants who practiced a three-week mindfulness (

Whitesman 2020;

Zhu et al. 2021). Mindfulness can improve people’s quality of life significantly by increasing inner happiness and building better relationships in secular life (

Barnes et al. 2007;

Evans et al. 2018;

Grossman et al. 2004).

Next, we turn to the literature about place to explore the types of physical space and settings where these practices have been and are being conducted.

1.3. Buddhist Contemplative Places

What does Buddhist literature and instruction say about where to practice mindfulness, and how is this manifest in the places that have been designed or chosen for this purpose? Places that are dedicated to the practice of Buddhism in the past and present include different forms of temples, monasteries, and retreat centers globally. After reviewing the physical Buddhist places of Mahayana (including Vajrayana) and Theravada Buddhist traditions, as well as the key characteristics of the favorable places for practice that Buddha and Buddhist teachers have mentioned in the sutras as suggestions for practitioners, especially beginners, we identified three recurring qualities: (1) quiet; (2) solitude; (3) and nature.

1.3.1. Quiet

The Buddhist Vinaya stated that the top obstacle to meditation is noise; therefore, places for meditation should be relatively quiet, preferably without any noise, just as if one is on the moon (

Lodro 2010). Most people would need a quiet place and the most favorable environment for practice is usually one that reflects the psychological condition that one wishes to achieve (

Khyentse 2012). The great Milarepa said that in such a quiet place, Samadhi (a state of profound and utterly absorptive contemplation of the Absolute that is undisturbed by afflictions) would naturally arise without much effort (

Milarepa 1999). According to Buddhist teachings (e.g.,

The Way of Bodhistsattva, the

Thirty-seven Practices of Bodhisattvas), the principle is that, if one’s mind is preoccupied, one is more likely to get distracted by the thoughts coming in and out, or it would take a long time for the mind to first settle down before entering the state of mindfulness. By abiding in a quiet place, it allows one to enter the state of practice much sooner than being in a very distractive environment to start with.

1.3.2. Solitude

Countless sutras and teachings of the previous great masters emphasize the importance of finding a suitable environment for beginners to learn Buddhist meditation practices. Such environments are often referred as solitary places.

The Commentary on Mahayana Teachings says that the beginner’s body must stay away from bustle and reside in solitude. Only in this way can one’s mind be regulated (

Sodargye 2015).

The Questions of Purna (

84000 2021b) states ‘By devotion to places of mountains and forests, the source of good qualities will be increased’. Resorting to solitary places can assist us to abandon attachment to the five desires connected with the five senses: form, sound, aroma, taste, and touch (

Online Buddhist Dictionary 2022). Isolation in peaceful empty solitude is very highly praised by all Buddhas. Therefore, let aspiring bodhisattvas always put their trust in solitude.

Maharatnakuta Sutra (trans.

Chang 1983) mentioned that beginners should reside in the solitary place in order to make their mind quiet and docile. Atisha also said that one shouldn’t leave the solitary place until one has reached a stable state; practitioners must reside in the solitary place to avoid being distracted by external objects (

Sodargye 2014). Many other great doctrinal teachings also provide strong support for this, such as

Finding Rest in the Nature of the Mind (

Longchenpa 2017), and

Words of My Perfect Teacher (

Rinpoche 2010). In short, Buddhist teachings suggest practitioners go to places that are away from chaotic environments and reside in solitary places.

What are the characteristics of a solitary place? While an intuitive definition is to be alone or isolated from other people, we observe that the key function of solitary experience is to help the practitioner minimize distractions of the mind, which may be achieved amongst others. For example, one such place dedicated to Buddhist study and worship is Larung Gar Buddhist Academy in China (

Figure 1). At first sight, there are thousands of people living and studying in this remote settlement, and there are many voices chanting and lecturing, which does not make it seem a solitary place. However, H.H. Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok once said that although there may be many people in this place, everyone’s mind is tamed and docile (

Zhicheng 2018). Because of this, the atmosphere of the place can reduce the level of distraction, which facilitates practice. Hence, this also accords with the definition of a solitary place. Arguably, some environments are better at helping one’s mind to calm down and reside in the state of mindfulness than others.

1.3.3. Nature

Nature is an important element in Buddhist places, evidenced from the Lumbini Garden where the historical Buddha was born, the Bodhi tree that Buddha sat underneath for his enlightenment and, for later teachings, to the later retreat sites and Buddhist monasteries located in nature (

Figure 2b–d). Natural elements are visible in traditional Buddhist paintings (such as Thangka), bearing both explicit and implicit meanings, as well as in the literature. For example,

The Way of Bodhisattva (

Shantideva 2008) stated that “In woodlands, haunt of stag and bird,/Among the trees where no dissension jars,/It’s there I would keep pleasant company!/When might I be off to make my dwelling there?/When shall I depart to make my home/In cave or empty shrine or under spreading tree,/With, in my breast, a free, unfettered heart,/Which never turns to cast a backward glance?…” As the

Cloud of Jewels Sutra (

84000 2021a) said, in order to get rid of the thirty-one types of negligence, such as fear, greed, and aggression, one should abide in the silent aranya (Skt.). Remote and uninhabited places of this kind, such as a forest or wilderness, are praised in many Buddhist texts as the ideal environment to practice the Dharma.

The Mahayana Sutra of Previous Lives and Contemplation of the Mind-Ground (

Giebel 2021) also commented on how aranya is the place where the past Buddhas have attained enlightenment, and aranya has innumerous amounts of merits which practitioners should aim to abide (Chapter 6). Hence, nature or the natural environment has a quality that is of great help to practice.

In summary, characteristics of places most frequently mentioned in the Sutras and Buddhist arts are quiet and solitude, including being away from everyday distractions, and nature or natural elements, including natural sounds, views, aromas, and vegetation, e.g., trees, grassland. These are the main qualities that would appear to help a practitioner on his or her path of mindful meditation practice. However, does a place possessing these three qualities in turn make practitioners more contemplative? Does this mean for a space to be contemplative it must have these three qualities? Furthermore, can these qualities be found and experienced in a contemporary urban environment? These questions will be discussed in the following case study.

2. Methods

We conducted a case study of a contemporary Buddhist center in the UK—Kagyu Samye Dzong London (KSDL), using mixed methods to collect and analyze data related to the design, management and use of the center for formal meditation and other Buddhist activities and rituals. This research has been approved by the Faculty Research Ethics Committee, [University withheld for peer review].

The following section explains the study design, specifically semi-structured interviews, questionnaires, and participant observation, to investigate the relationship between the Buddhist contemplative space and mindfulness practice.

2.1. Case Study Introduction

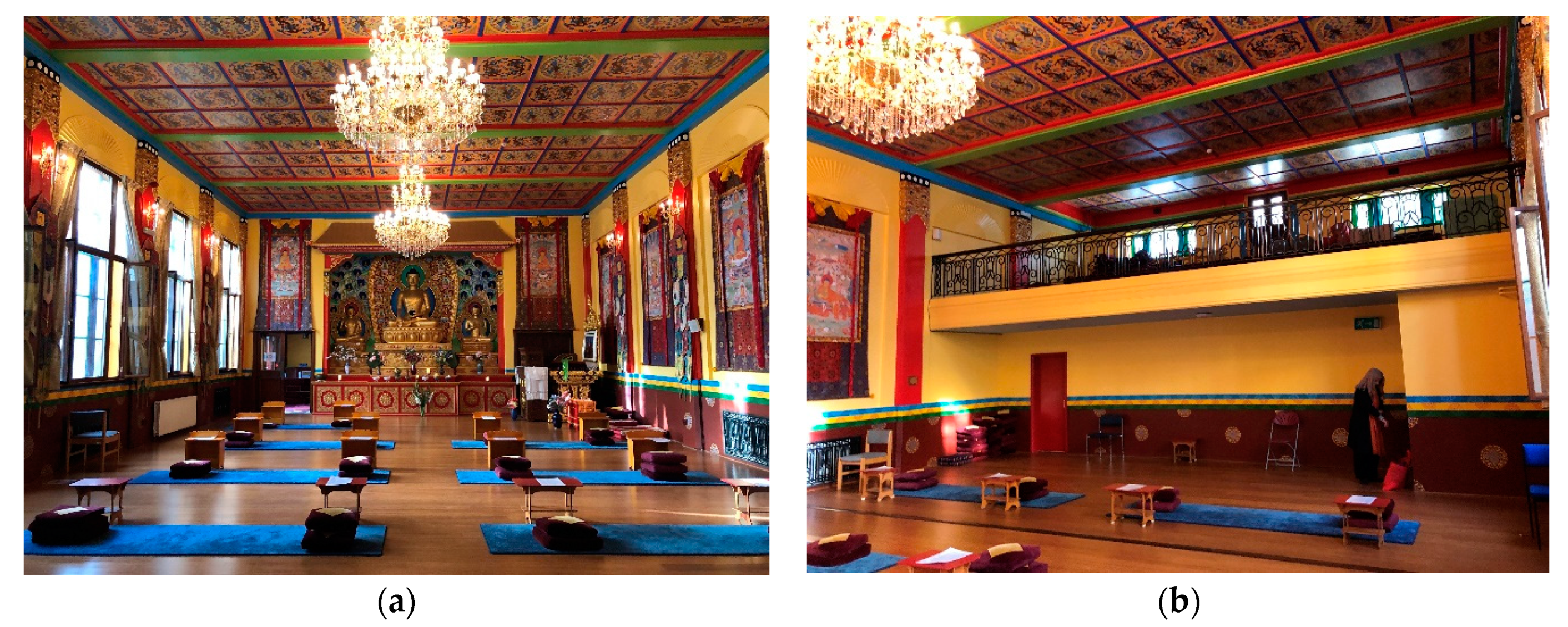

The Kagyu Samye Dzong London (

Figure 3) officially opened in June 2010. It belongs to the Kagyu tradition, one of the four main schools of Tibetan Buddhism, and is a branch of the Kagyu Samye Ling Monastery in Scotland (est. 1967). The building itself originally served as the first free public library in London in the 1890s and it was also a base to launch a number of public health initiatives. The center runs a program of courses and workshops focusing on meditation, mindfulness, Buddhism, and holistic therapies, and it also provides venues for community activities and alternative practitioners as well as a qualified Tibetan doctor who holds regular clinics for patients receiving treatment using traditional Tibetan methods (

KSDL 2021). The center is located near central London, with the nearest bus stop within 2 min walking distance, and the nearest underground station Bermondsey around 11 min walking distance. This urban location and its high accessibility have made Buddhist meditation and Buddhist teachings easily accessible to Londoners and beyond, especially beginner meditators.

2.2. Semi Structured Interview

A semi-structured interview (SSI) was conducted with the resident teacher and director of KSDL, Lama Gelongma Zangmo, who has over 40 years of experience (since 1977) in studying and practicing Buddhism. She has been helping to run KSDL since 1998. She is a proficient practitioner herself (who has over eleven and a half years in total spent in retreat), a teacher who gives teachings of Buddha Dharma, as well as the director of the center who oversees organizational and management work. The SSI was conducted in late October 2021 via telephone. The interview was recorded and transcribed. The SSI was composed of eight questions following the four sub-themes, exploring the relationship between the physical space and mindfulness practice (

Table 1).

2.3. Questionnaire

The questionnaire took the form of an online survey of practitioners who meditate at the KSDL. It aimed to identify the spatial attributes and elements that influence people’s practice the most (both positively and negatively). The questionnaire was distributed online via email. It contained 20 questions, consisting of three main parts: (a) introductory questions about people’s mindfulness practices, (b) about their practice experience at the center or the places that they practice the most, and (c) demographic questions (gender, age, religious belief, occupation).

Twelve participants voluntarily choose to participate after receiving recruitment emails that were sent to KSDL (

Table 2 and

Appendix A). In brief, the sample included: twelve females; seven Buddhists; five other religions or non-Buddhists; and participants had all previously practiced mindfulness meditation in KSDL. All gave their consent to take part in the online survey. There was no attempt to find a homogenous group of participants in terms of gender, age, religious belief, profession, nor a similar level of mindfulness practice. Apart from gender (all female), the participants represent a range of demographic variables.

2.4. Participant Observation

Participant observation is “the process of entering a group of people with a shared identity to gain an understanding of their community” (

SAGE 2017), which can be achieved by “gaining knowledge and a deeper understating of the actors, interaction, scene, and events that take place at the research site” (

SAGE 2017).

The primary author attended two meditation sessions at the KSDL in September 2021. Due to COVID-19 regulations at the time, the center only opened from 14:00 to 16:30 on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons. The afternoon program started with a light offering in the garden space. The attendants then entered the main shrine room from the back door, started by chanting a short prayer, and a 40-min meditation session guided by the resident teacher Lama Zangmo without instruction, followed by a 15-min break, and then repeated the 40-min meditation session without the resident teacher. The primary author attended both afternoon sessions in one week. On Wednesday, around 23 people came, whereas Saturday welcomed 27 people to the center. Through the two-afternoon experience at KSDL, the primary author was able to spend time with the other people who came to the center and have brief conversations with them during the break, closely observing their actions. The primary author’s intention was explained to those in the conversation and to the lama who oversaw the center.

The participant observation involved taking in as much as possible the surrounding environment of KSDL as the objective part; it also involved participating in the meditation sessions as a practitioner to experience the space in person. The process included taking notes at the end of each day, and attending all sessions, including the conversation during the break for the full experience. The primary author was able to gain more understanding of the group as well as the center.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Environment Influences the Practitioner

Both the literature and the results from the interview and questionnaire point towards the answer that, yes, the location where one is practicing does have an influence on the practitioner, evidenced by the environment that people prefer (

Figure 8), the choice of the location for KSDL next to Bermondsey Park, and the locations that the Buddha and great masters suggested. There is a rich number of teachings and texts, as mentioned above, stating and suggesting where one should abide, especially beginners, who are more likely to be influenced by the environment. The questionnaire results (

Figure 8) also show that the space influences one’s practice as people’s attitudes toward different environments vary. Practitioners tend to prefer remote rural environments over busy urban environments as they consider the former more favorable and beneficial for their practice. Of the practitioners, 83.3% made a rating on a range between −5 to 5. Only 16.7% rated ‘not applicable to them’. This result in itself is evidence for the influence of the environment to the practice.

Such phenomena are also confirmed by the statement from the director of KSDL, who is a very proficient practitioner herself: “the space will influence your practice for a long time and for myself, also. Especially if you’re a beginner, it will affect you even more. But we are all affected by our surroundings, in different ways, we are affected by our surroundings, and by the people around us.” For example, if one is in a very agitated place, or in a place that is not conducive, or not supportive, of Dharma, it will have a different feel. The director of KSDL also gave examples of the great lineage of Buddhist masters who initially look for a place either of solitude or an acquired place, where they can withdraw from other distractions and focus on their mind. The literature also supports this point.

In the case of KSDL, it has an environment that is quite encouraging and conducive for practice, due to it being created purely for the purpose of practice and study of the Dharma. It was originally built as a library in 1892, which was also a temple to learning. As such, it could be transformed easily and positively into a Buddhist center for the purpose of studying, contemplating, and practicing of the Dharma. This is also where the center is distinguished from one’s own home. From both the interview and questionnaire results, it is shown that one is more likely to have a positive experience at the center. One’s home can be dedicated to many purposes, whereas the contemplative place is usually totally focused around the Dharma, where all the activities including mindfulness practice are focused around the Dharma, the layout is focused on the Dharma, and the main purpose is the Dharma. Hence, the atmosphere (which 100% of participants value importantly) and all the elements are intended to be designed to facilitate such a purpose. In the instance of KSDL, the main shrine room is the heart of the center. Lama Zangmo noticed that people generally find that their practice is better at the center than it is at home, stating “It is easier for them to practice there than at home”.

Despite the claims that mindfulness can be practiced anywhere, some places are more favorable than others, especially for beginners. Therefore, the environment does have a significant influence on the practitioners. As the contemplative space is part of the environment, it also influences people’s practice to a certain extent.

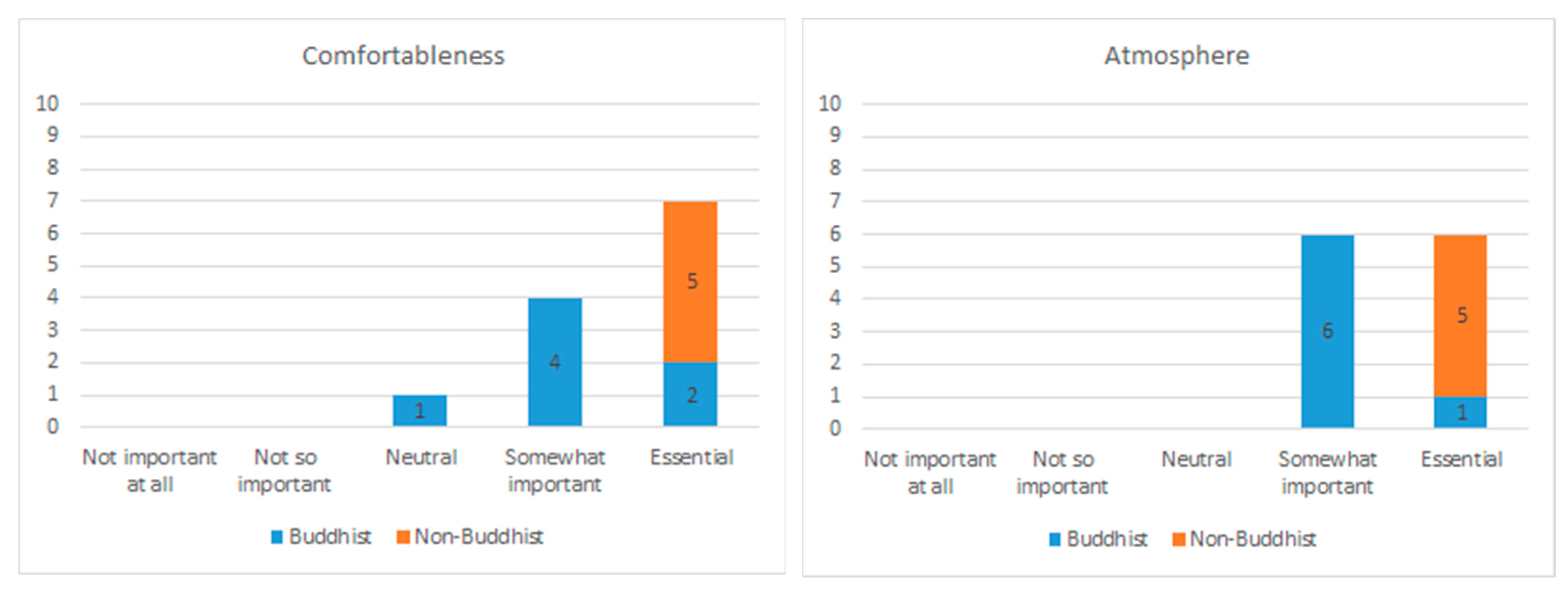

4.2. Factors Influencing the Practitioner

The question then follows, what exactly is it within the contemplative space that has this influence? To rephrase the question more precisely, what are the qualities in the contemplative space that facilitate the practice? From the literature, “quiet”, “solitude”, and “nature” are the top three qualities. From the questionnaire, the top three elements are “atmosphere”, “comfortableness”, and “quietness” (

Figure 9). From the interview, the director of KSDL suggested three points: “away”, “blessing”, and “representation of the Three Jewels”. These qualities can be categorized into tangible aspects and intangible aspects. There are the physical tangible aspects which one is able to point out, for example, the natural view, the natural lighting, focus objects (Buddha stature); and there are the intangible aspects, such as blessing, which is one crucial aspect in Buddhist practice.

The questionnaire results (

Figure 8) show how practitioners rated the importance of the qualities and elements of the environment which may influence their practice. For the individual elements that have been mentioned above in the literature, “quietness” has been considered to be quite important for the practitioners, regardless of their religion or length of practice. These are evident in the questionnaire—10 out of 12 people think quietness is somewhat important. Such a statement is also evident in Lama Zangmo’s interview, where she said the less noise the better. From the interview, Lama Zangmo first suggested “away” as one of the three most important elements which would facilitate practitioners with their practice. When people are withdrawn from their usual day to day activities, then one is not surrounded by all the things that will pull him or her away from the practice, such as their computer or phone. The essence here is to remove all types of distractions that will influence one and make one do something else. This response to the quiet (absence of distractive noises) and solitude (where one is less likely to be disturbed) is mentioned in the literature. People’s preference towards “solitude” and “quietness” is also visible from

Figure 7, where they favor remote rural environments over busy urban environments.

Second is nature or natural elements. Of the practitioners, 75% consider that natural sounds would be a positive influence for their practice and 66.7% of participants consider natural lighting to be somewhat important/essential. A similar statement was confirmed in the interview with Lama Zangmo, highlighting the importance of natural elements in the environment. The importance of nature was expressed physically through the garden, which acts as a buffer zone as well as an outdoor shelter space (with three canopies). Therefore, it prepares people for their practice in the shrine room, and it also prepares people before they go back to the mundanities of daily life. Lama Zangmo said that they have always been trying to nurture nature at the center as much as they can: “I think nature has a very healing, good influence on all of us. And so to have plants and greenery, the more we can have the better”. These kinds of spaces, such as gardens and outdoor spaces, are important in a city like London. Although they influence people in a subtle way that people do not always recognize, they are certainly very precious. On the one hand, it provides a restful place from the busy urban environment, and on the other hand, because of COVID-19, people can use them in order not to have to come into the rest of the building. Coincidentally, not only do Buddhist practitioners deeply value nature, natural elements, and quietness, modern environmental psychology also considers nature and natural elements to be beneficial and have the healing and calming effects that one may need (

Bell 2011).

There is one crucial element which is not tangible nor physical, but is indispensable for Buddhist practitioners—blessing, the second point that Lama Zangmo raised in the interview. It was clearly stated that “It’s also good to have a place that is blessed, a blessed place that is blessed by great beings by great masters. If Great Beings have practiced in that place, it’s also supposed to be good for future generations and for future practitioners.” Such a statement is supported by the questionnaire results, where a participant described KSDL to be blissful, which was important for her practice.

Lastly, it is important to have representations of the Three Jewels, which represents a positive influence, for example, a shrine with Buddha statue, the Dharma texts, and the Sangha. In fact, as the director of the center and the leading teacher for the practices, as well as a proficient practitioner, Zangmo emphasized the representation of the Buddha the most. In the question asking “if you were to choose only one element to remain in the space (taking everything else away) for the practice, what would you choose?”, Lama Zangmo answered without hesitation: “The representation of the three jewels, the Buddha”. The swift response itself indicates the assurance and its importance from her perspective. The survey showed that 50% of participants consider the Buddha statue to be of positive influence. Due to different beliefs and religion, not all participants consider the Buddha statue, the representation of the Three Jewels, as being so important (

Appendix A—Buddha statue).

In fact, these two qualities intertwined with each other in many instances. The intangible blessings can be delivered through the physical tangible outer representations of the Three Jewels. Both physical tangible qualities and intangible qualities are indispensable in the contemplative space and in influencing one’s practice. It is evident here that, by having the blessing and representations of the Three Jewels, a space can be made contemplative for Buddhists. Situated in central London with busy traffic nearby, KSDL does not quite fulfill the qualities of “quiet” and “solitude” at first glance. However, practitioners who come to the center would still consider this place a Buddhist contemplative space. The reasons being the last two points raised by Lama Zangmo, which are key to being contemplative.

4.3. How the Space Influences the Practitioner

To discuss this theme, the three words that Lama Zangmo chose to describe the shrine room are presented first: inspiring, colorful, and moving. Because of what it represents, the atmosphere in the room—the Three Jewels, and all the Buddhists there and the life story of the Buddha on the Thangka—all of that together is a source of inspiration to pursue further by seeing the representation of the Three Jewels. The three words are related to the atmosphere of the space in Samye Dzong which all participants rated somewhat important/essential.

As for inspiring, although it cannot be guaranteed that this center will be inspiring for people, it is certain that “if people come looking for the Dharma, for the Three Jewels, they will find it here. And that we are doing our best to represent the Three Jewels”. Hence, the community of KSDL have put in the effort of creating this space, and then made the effort to keep it clean and keep it nice and tidy.

As for colorful, the questionnaire shows that the color of the room is not considered to be very important. Only 25 % of participants rated it “somewhat important” (

Figure 10). It may be argued that people have different preferences; some may prefer more simple styles, whereas others may prefer rich and strong colors. For example, some people will feel better meditating in a in a very simple room, which are popular in the Zen style. Or temples in Sri Lanka, where it is completely white inside; apart from the golden Buddhas, everything is white. In contrast, the center of KSDL is in the traditional Tibetan style. Such drastically different styles have developed due to the environment and the climate of the different countries. Because Sri Lanka is a very tropical country, a very hot and very colorful country outside, one would feel the need for a cool space to meditate. Whereas the Tibetan area is quite the opposite, very cold outside, where one would require warmth to sit and meditate. These differences are not suitable to be labeled with “better” or “worse” as they were developed partly due to the culture, the climate, and the environment in each individual country. This is very much about people’s preferences. As long as the practitioner feels comfortable, then they can choose whatever the style that suits him or her.

For moving, Lama Zangmo explained the following: “So I think it is that they’re looking for something. They are looking for the spiritual connection. And I think maybe they will find it there, because it is hard to find a real genuine spiritual connection online, so just sitting and looking at a screen.” Again, this refers back to the representation of the Three Jewels and the idea of blessings and can link to the concept of inspiring.

4.4. The Extent to Which the Space Influences the Practitioner

From the above results, it is evident that the environment would influence the practitioner. In the survey results, a range of elements have different degrees of impact on a person’s practice. However, does this mean that by having an ideal environment that would be the end of the practice? Does this mean that by having a contemplative space, the quality of practice will be ensured? Not necessarily.

From the primary author’s experience at the center, having four meditation sessions of the same length for comparison, it suggests something more. With or without the presence of a residential teacher, the mindfulness meditation experience varies. In the sessions with the presence of teacher, the primary author could focus better. With all physical settings being the same—the same room, same decoration, same position, same meditation cushions—the experiences were different. This suggests that the external physical contemplative space is not the decisive element in one’s practice.

Another example is the “quiet”. There was building construction going on during the practice; therefore, it was not really a quiet place at the time in KSDL. However, people were still able to concentrate in their meditation. Although quiet has been said to be very important, other practitioners are not likely to practice in a totally silent place. Lama Zangmo explained that “If you’re in the countryside, you have birds, you have other animals, you have other sounds, but ideally, less noise is better. But people also need to develop flexibility, not to get annoyed, not to be irritated.”

In the end, the aim of all Buddhist practices including mindfulness is to achieve enlightenment, which is beyond concept, beyond form. These are the means for one to actualize awareness and truth (

Khyentse 2021). The external physical contemplative space is also a tool to help achieve this purpose. In the famous analogy of the finger pointing to the moon, the goal is to see the moon; similarly, both mindfulness practice and the ideal environment where it is practiced are the “fingers” pointing towards the “moon” of enlightenment. Yet, the idea of the contemplative space should not be bound to something only physical. To conclude, it is certain that practitioners are influenced by their surroundings both in a positive and in a negative way. Then, as one gets stronger at the practice, maybe the environment becomes less important. One should aim to transcend beyond the physical boundaries as the goal is beyond the physical.

Therefore, it is valid to point out that the contemplative space is not only limited to somewhere physical, external to the mind and body of the practitioner. It is, however, an important support for the practitioners, especially for beginners, where they can familiarize themselves with the practice and consolidate the practice in a favorable environment without being overwhelmed by the challenges. Nonetheless, abiding in such a contemplative space does not automatically guarantee the state of mindfulness. Instead, as said, it is a means to support the mindfulness practice, which aims to facilitate the practitioners to go beyond, and ultimately, reach the state of realization and the contemplative space within. For non-Buddhists, the space with such qualities may provide people with a moment of peace and calm, but for Buddhists, such a space is a gateway to the more pervasive and unbounded contemplative space that exists everywhere.

4.5. Limitations and Suggestions

There were a number of practical difficulties encountered during the research. One challenge was to recruit participants. Due to the impact of the pandemic, the physical access to the center and contact with possible interviewees and practitioners posed many difficulties. There was also a shortage of time due to the national lockdown. The center was closed in summer and only open for limited hours later during the year. This resulted in the low number of questionnaire responses and interviewees, which limited the depth of discussion from the quantitative aspect. The amount of data collected by the time of writing the paper was lower than expected. Therefore, the strength of the conclusions are limited by these outcomes.

4.6. Future Suggestions

To further test the claims and the theory in this study, further work is needed. Most importantly, the data collection could be extended for a longer time period to allow more practitioners to participate, increasing the amount of questionnaire responses and interviewees. This would enable the study to be approached from a quantitative perspective. Comparative case studies could be undertaken to provide a variety of empirical evidence and perspectives as well.

5. Conclusions

This paper explores the Buddhist idea of contemplative space through both a literature review of the traditional idea of Buddhist mindfulness practice and Buddhist contemplative space, and the case study of a contemporary Buddhist center in central London in the West. From the literature review, the top three qualities of a favorable place for mindful Buddhist practice are “quiet”, “solitude”, and “nature”. Based on this, we analyzed the design and perception of KSDL, exploring the relationship between space and practice as evidenced by interview, questionnaires, and participant observation results. This KDSL case study revealed that in addition to these three physical spatial attributes, there are certain qualities that make a space contemplative and, hence, support mindful intention in a more profound way; in this instance, the representation of the Three Jewels and the intangible element of blessing contribute to the essence of the contemplative space. Places with such qualities are found to be favorable for practitioners and facilitate mindfulness practices. Furthermore, in the case of Kagyu Samye Dzong London, such urban centers offer a possible place of calm and relaxation for Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike. Meanwhile, practitioners are encouraged to progress beyond physical limitations and explore the true mindfulness within.