The Intention of Becoming Religiously Moderate in Indonesian Muslims: Do Knowledge and Attitude Interfere?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Religious Moderation and Religious Extremism

- Tawassuth, which is the attitude of always taking the middle way or the straight path with truth, without being extreme (excessive) in one option/way/point of view or practice;

- ’Itidal, which means balance and justice based on the principle of fairness that is proportional and not extreme or excessive;

- Tasamuh, which is intended to recognize and respect diversity in all aspects of life;

- Shura relies on consultation and problem solving through deliberation to reach a consensus;

- Ishlah, which is involved in reform and constructive good deeds for ordinary people;

- Qudwah, which involves efforts to pioneer noble initiatives and lead human welfare;

- Muwwatanah accepts Indonesian nationality and plurality and commitment as a good citizen.

1.2. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Intentions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

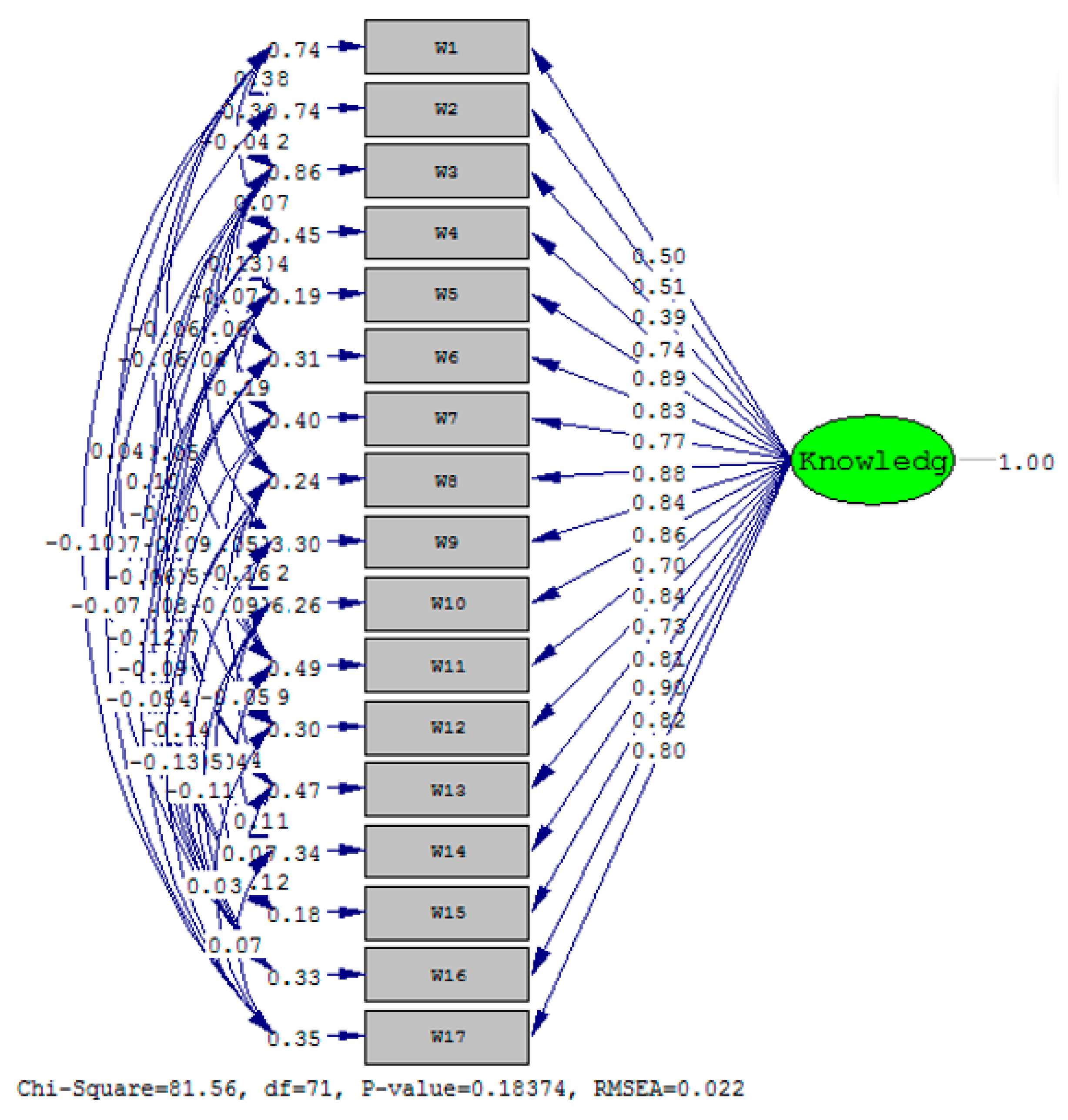

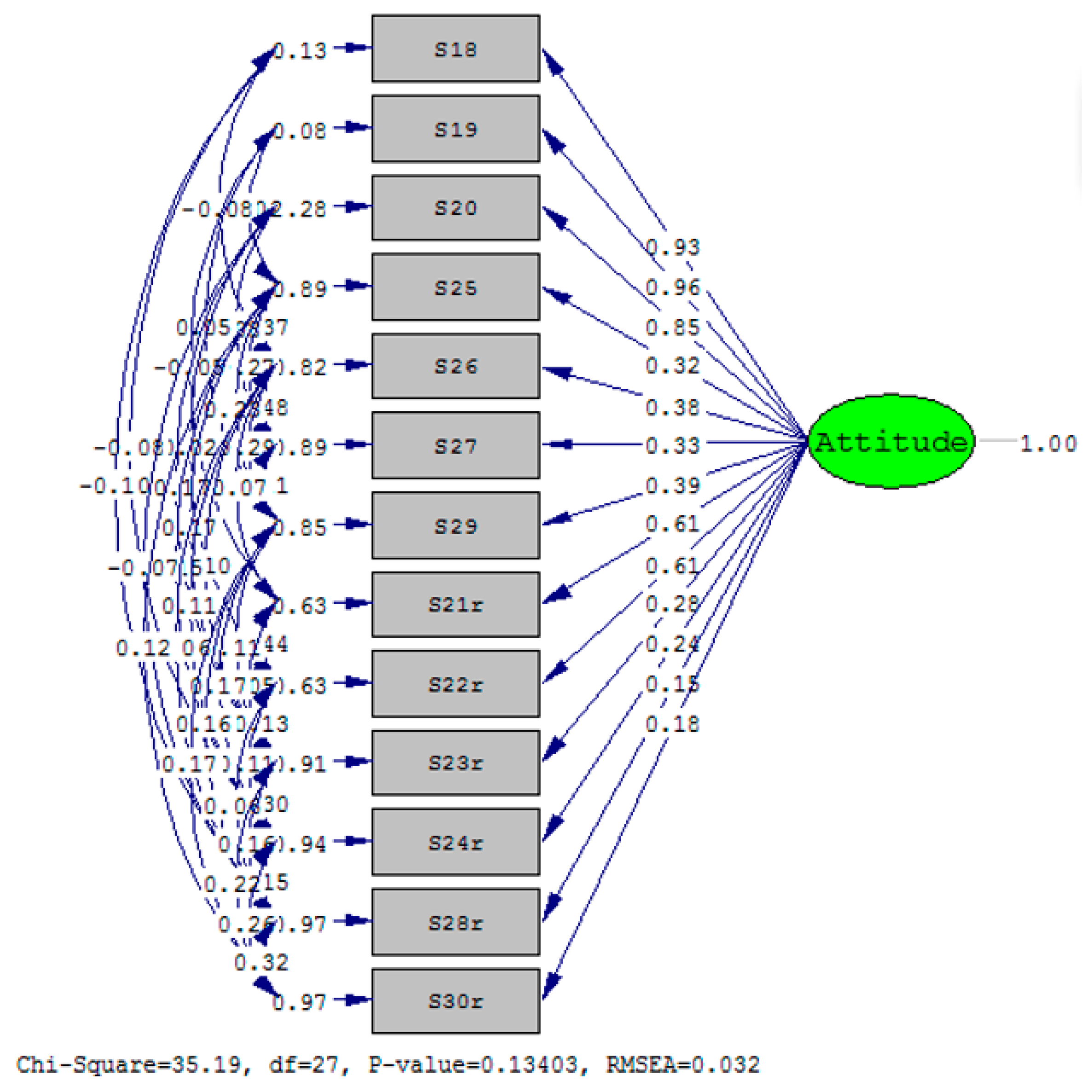

3.1. Results of the Construct Validity Test Using Confirmatory Factor Analysis

- Islamic Religious Moderation Knowledge Scale

- 2.

- Islamic Religious Moderation Attitudes Scale

- 3.

- Islamic Religious Moderation Intentions Scale

3.2. Multiple Regression Analysis

- The attitude variable’s regression coefficient was 0.318 with sig = 0.000, indicating that the attitude variable has a significant effect on the intentions of Islamic religious moderation.

- The regression coefficient for the knowledge variable was 0.263 with sig = 0.000, indicating that the knowledge variable has a significant effect on the intentions of religious moderation.

- The regression coefficient for the age variable was 0.013 with sig = 0.822, indicating no significant effect between age and the intentions of religious moderation; there is no guarantee that the elderly have better intentions to become moderately religious.

- The regression coefficient for the gender variable was 1.226 with sig = 0.214, indicating no significant effect between gender and the intentions of religious moderation.

- The regression coefficient for the educational background was 1.043 with sig = 0.292, indicating no significant effect between Islamic universities and Islamic schools and non-Islamic universities and non-Islamic schools on the intentions of religious moderation.

- The regression coefficient for religious affiliation was −0.183 with sig = 0.862, indicating no significant effect between Nahdatul Ulama and non-Nahdatul Ulama religious affiliations on the intentions of religious moderation.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dimension | Indicators | Item Number | English Version | Indonesian Version |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Availability of information about Islamic religious moderation | When and from who do people know about religious moderation | 1 | I know religious moderation has been around for a long time, since school/boarding school days. | Saya mengetahui moderasi beragama sudah lama sejak zaman sekolah/pesantren. |

| When and from who do people know about religious moderation | 2 | My teacher/parents/lecturer taught me about religious moderation. | Guru/Ustadz/Orang Tua/Dosen saya mengajarkan saya tentang moderasi beragama. | |

| When and from who do people know about religious moderation | 3 | My social environment indirectly made me know and understand religious moderation. | Lingkungan saya secara tidak langsung membuat saya mengetahui dan memahami moderasi beragama. | |

| Reasoning about Islamic religious moderation | Tawassuth (middle path/straight path with truth and not extreme in one view) | 4 | Religious moderation is at the core of Islamic teachings, which promote a sensible way without being extreme. | Moderasi beragama ada pada inti ajaran Islam, yang mengedepankan jalan tengah tanpa bersikap ekstrim (berlebihan). |

| I’tidal (balance and justice) | 5 | Religious moderation reduces violence and is fair in practicing religion. | Moderasi beragama adalah mengurangi kekerasan dan mampu bersikap adil dalam melakukan praktik keagamaan. | |

| Tasamuh (respect for the diversity of life) | 6 | Religious moderation is when a person can respect differences of opinion. | Moderasi beragama adalah saat seseorang mampu menghormati perbedaan pendapat. | |

| Shura (deliberation for consensus agreement) | 7 | Religious moderation entangles consultation and problem-solving through deliberation to reach a consensus. | Moderasi beragama yaitu bersandar pada konsultasi dan penyelesaian masalah melalui musyawarah untuk mencapai konsensus. | |

| Ishlah (participation of constructive goodness for the benefit of altogether) | 8 | Religious moderation promotes constructive good deeds for a familiar audience. | Moderasi beragama mengedepankan perbuatan baik yang konstruktif untuk khalayak bersama. | |

| Qudwah (good initiatives for the glory and welfare of humans) | 9 | Religious moderation is an understanding that can lead to human well-being. | Moderasi beragama merupakan satu pemahaman yang dapat membawa pada kesejahteraan manusia. | |

| Muwwathanah (accommodating the state, nation, and culture) | 10 | Religious moderation confesses diversity within countries and nations and aims to maintain balance and harmony in the state. | Moderasi beragama adalah mengakui keragaman di dalam negara dan bangsa, serta bertujuan menjaga keseimbangan dan keharmonisan dalam bernegara. | |

| Identification of the characteristic Islamic religious moderation | Tawassuth (middle path/straight path with truth and not extreme in one view) | 11 | Moderate people can take the middle ground when there is a conflict of opinion regarding teachings/mazhab/traditions. | Orang yang moderat adalah mereka yang mampu mengambil jalan tengah manakala terjadi pertentangan pendapat terkait ajaran/mazhab/tradisi. |

| I’tidal (balance and justice) | 12 | Moderate people have firmness in behavior but still pay attention to the principle of justice in others. | Orang yang moderat adalah mereka yang memiliki ketegasan dalam bersikap, namun tetap memperhatikan prinsip keadilan pada orang lain. | |

| Tasamuh (respect for the diversity of life) | 13 | Moderate people don’t put out words that can offend others. | Orang yang moderat adalah mereka yang tidak mengeluarkan kata-kata yang dapat menyinggung orang lain. | |

| Shura (deliberation for consensus agreement) | 14 | Moderate people are those who put forward deliberation to achieve the common good. | Orang yang moderat adalah mereka yang mengedepankan musyawarah untuk mencapai kemaslahatan bersama. | |

| Ishlah (participation of constructive goodness for the benefit of altogether) | 15 | Moderate people put forward good deeds for a familiar audience when there is a difference of opinion. | Orang yang moderat adalah mereka yang mengedepankan perbuatan baik untuk khalayak bersama, saat terjadi perbedaan pendapat. | |

| Qudwah (good initiatives for the glory and welfare of humans) | 16 | Moderate people are those who can take the initiative to glorify others. | Orang yang moderat adalah mereka yang dapat berinisiatif untuk memuliakan orang lain. | |

| Muwwathanah (accommodating the state, nation, and culture) | 17 | Moderate people accept the nationality, statehood, and local culture of Indonesia. | Orang yang moderat adalah mereka yang menerima kebangsaan, kenegaraan dan budaya lokal Indonesia. |

| Dimension | Indicators | Item Number | English Version | Indonesian Version |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beliefs | Qudwah (good initiatives for the glory and welfare of humans) | 18 | I believe religious moderation is necessary to maintain the harmony of national life. | Saya meyakini moderasi beragama sangat diperlukan untuk menjaga keharmonisan kehidupan berbangsa |

| Tasamuh (respect for the diversity of life) | 19 | For me, religious moderation is indispensable for a multicultural Indonesian society. | Bagi saya, moderasi beragama sangat diperlukan bagi masyarakat Indonesia yang multikultural | |

| Ishlah (participation of constructive goodness for the benefit of altogether) | 20 | I believe religious moderation is essential so that there are no ethnicity, religion, race, or inter-group relation issues among the community. | Saya meyakini moderasi beragama sangat diperlukan agar tidak terjadi isu sara di kalangan masyarakat | |

| Tawassuth (middle path/straight path with truth and not extreme in one view) | 21 | Religious moderation is not necessary because religion already has its way of truth. (Reverse coded) | Moderasi beragama tidak diperlukan, karena agama sudah memiliki jalan kebenarannya masing-masing | |

| Tawassuth (middle path/straight path with truth and not extreme in one view) | 22 | Religious moderation is not necessary, as it reflects indecision in religion. (Reverse coded) | Moderasi beragama tidak diperlukan, karena mencerminkan ketidaktegasan dalam beragama | |

| Emotions | Tasamuh (respect for the diversity of life) | 23 | I feel uncomfortable when I disagree with others about differences in teachings/mazhab/traditions. (Reverse coded) | Saya merasa tidak nyaman saat berbeda pendapat dengan orang lain terkait perbedaan ajaran/mazhab/tradisi |

| Tasamuh (respect for the diversity of life) | 24 | I don’t feel guilty about having to put out words that could offend others in defense of my beliefs. (Reverse coded) | Saya tidak merasa bersalah jika harus mengeluarkan kata-kata yang dapat menyinggung orang lain, demi membela keyakinan saya. | |

| Tasamuh (respect for the diversity of life) | 25 | I feel happy to respect other people from any background. | Saya merasa senang memuliakan orang lain dari berbagai latar belakang apapun | |

| Shura (deliberation for consensus agreement) | 26 | I like to accommodate other people for deliberation to find a middle ground when there are differences of opinion. | Saya senang mengakomodir orang lain untuk bermusyawarah mencari jalan tengah saat terjadi perbedaan pendapat. | |

| Past behaviors associated with Islamic religious moderation | Shura (deliberation for consensus agreement) | 27 | I can intercede with friends with different opinions about teachings/mazhab/and traditions. | Saya dapat menengahi teman yang sedang berbeda pendapat tentang ajaran/mazhab/tradisi |

| Tasamuh (respect for the diversity of life) | 28 | When a friend reads a verse of the Qur’an in the dialect of his native region, I blame him and ask him to read the Qur’anic verse correctly. (Reverse coded) | Saat ada teman yang membaca ayat alquran dengan dialek daerah asalnya, saya menyalahkannya dan memintanya untuk membaca ayat alquran dengan benar. | |

| I’tidal (balance and justice) | 29 | I try to avoid extreme attitudes in imposing my beliefs on others. (Reverse coded) | Saya berupaya untuk menghindari sikap berlebihan dalam memaksakan keyakinan saya pada orang lain. | |

| Ishlah (participation of constructive goodness for the benefit of altogether) | 30 | I can commit an act of violence to stand up for my religion. (Reverse coded) | Saya mau melakukan suatu tindakan kekerasan demi membela agama saya. |

| Dimension | Indicators | Item Number | English Version | Indonesian Version |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Directing the mind; the conscious decision to choose a moderate Islamic cleric | Mind directed | 31 | I’m not sure that moderate Islamic cleric has answers to my life’s problems. (Reverse coded) | Saya tidak yakin bahwa ustadz/ustadzah yang moderat memiliki jawaban tentang masalah kehidupan saya. |

| 32 | Moderate Islamic clerics’ words/lectures always stick in my mind. | Ujaran/ceramah ustadz/ustadzah yang moderat senantiasa menempel di pikiran saya | ||

| 33 | I don’t need a moderate Islamic cleric preach. (Reverse code) | Saya tidak memerlukan ceramah ustadz/ustadzah yang moderat | ||

| The conscious decision | 34 | When watching for preaching in the media, my focus is often on Islamic clerics who can mediate differences in teachings/mazhab/traditions. | Saat mencari tayangan ceramah di media, fokus saya sering tertuju pada ustadz/ustadzah yang bisa menengahi perbedaan ajaran/mazhab/tradisi | |

| 35 | When I have a problem, I look for the opinion of the Islamic cleric, who tends to be moderate. | Saat memiliki persoalan, saya akan mencari pendapat ustadz/ustadzah yang cenderung moderat | ||

| 36 | I will watch the entire broadcast of the Islamic cleric, whose preaching leads to religious moderation. | Saya akan menonton full tayangan ustadz/ustadzah yang ujarannya mengarah pada moderasi beragama. | ||

| Directing the behavior to support a moderate Islamic cleric | Directing the behavior to watch and share | 37 | When watching Islamic cleric shows with religious moderation content, I like/share so that the content of his teachings is spread widely. | Saat menonton tayangan ustadz/ustadzah dengan konten moderasi beragama, saya akan memberikan like/share agar isi ajarannya tersebar luas |

| 38 | When watching Islamic cleric preaching with religious moderation content, I dislike/report it so that the contents of his teachings are not spread widely. (Reverse coded) | Saat menonton tayangan ustadz/ustadzah dengan konten moderasi beragama, saya akan memberikan dislike/report agar isi ajarannya tidak tersebar luas. |

References

- Abidin, Achmad Zainal. 2021. Nilai-Nilai Moderasi Beragama Dalam Permendikbud No. 37 Tahun 2018. [Religious Moderation Values in Permendikbud No. 37 Year 2018]. JIRA: Jurnal Inovasi Dan Riset Akademik 2: 729–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adawiyah, Rabiah Al, Clara Ignatia Tobing, and Otih Handayani. 2021. Pemahaman Moderasi Beragama Dan Prilaku Intoleran Terhadap Remaja Di Kota-Kota Besar Di Jawa Barat. [Understanding Religious Moderation and Tolerance of Adolescents in West Java’s Big Cities]. Jurnal Keamanan Nasional 6: 161–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, Icek. 1991. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50: 179–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, Icek. 2005. Attitudes, Personality, and Behavior, 2nd ed. New York: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Akhmadi, Agus. 2019. Moderasi Beragama Dalam Keragaman Indonesia. [Religious Moderation In Indonesia’s Diversity]. Balai Diklat Keagamaan Surabaya 13: 11. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Nuraliah. 2020. Measuring Religious Moderation among Muslim Students at Public Colleges in Kalimantan Facing Disruption Era. Inferensi: Jurnal Penelitian Sosial Keagamaan 14: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasoulia, Stella. 2020. From ‘Soft’ to ‘Hard’ to ‘Moderate’: Islam in the Dilemmas of Post-2011 Saudi Foreign Policy. Religions 11: 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beelmann, Andreas. 2020. A Social-Developmental Model of Radicalization: A Systematic Integration of Existing Theories and Empirical Research. International Journal of Conflict and Violence (Ijcv) 14: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, Sarah-Jayne, and Jean Decety. 2001. From the Perception of Action to the Understanding of Intention. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2: 561–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahri, Mohamad, and Ahmad Zainuri. 2019. Moderasi Beragama Di Indonesia. [Religious Moderation in Indonesia]. Intizar 25: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, Martin, and Icek Ajzen. 1975. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Gusti, Aria. 2016. The Relationship of Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intentions of Sustainable Waste Management on Primary School Students in City of Padang, Indonesia. International Journal of Applied Environmental Sciences 11: 10. [Google Scholar]

- Haddock, Geoffrey, and Gregory Richard Maio. 2008. Attitudes: Content, Structure, and Functions, 4th ed. An Introduction to Social Psychology: A European Perspective. Oxford: Blackwell, p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Hatak, Isabella, Rainer Harms, and Matthias Fink. 2015. Age, job identification, and entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Managerial Psychology 30: 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Junaedi, Edi. 2019. Inilah Moderasi Beragama Perspektif Kementerian Agama. [From the Ministry of Religion’s point of view, this is Religious Moderation]. Puslitbang Bimas Agama Dan Layanan Keagamaaan, Balitbang Dan Diklat Kemenag Ri 18: 10. [Google Scholar]

- Kamali, Mohammad Hashim. 2015. The Middle Path of Moderation in Islam: The Qurʼānic Principle of Wasaṭiyyah. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kementerian Agama, ed. 2019. Moderasi Beragama (Cetakan Pertama), 1st ed. Religious Moderation. Jakarta: Badan Litbang Dan Diklat Kementerian Agama Ri. [Google Scholar]

- Kourgiotis, Panos. 2020. ‘Moderate Islam’ Made in the United Arab Emirates: Public Diplomacy and the Politics of Containment. Religions 11: 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, Ramesh, Charles Ramendran, and Peter Yacob. 2012. E Ployees’ Fit to the Orga Izatio Al Culture A D The. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2: 35. [Google Scholar]

- Maghfiroh, Shinta Lailatul, Siti Rohmah, and Muhammad Hamdan Yuwafik. 2020. Reinterpretasi Makna Moderasi Beragama Dalam Konteks Era Pasca Kebenaran (Post-Truth). [In the Post-Truth Era, a Reinterpretation of the Meaning of Religious Moderation]. Hikmah, Uin Sunan Ampel Surabaya 14: 199–30. [Google Scholar]

- Maichum, Kamonthip, Surakiat Parichatnon, and Ke-Chung Peng. 2016. Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model to Investigate Purchase Intention of Green Products Among Thai Consumers. Sustainability 8: 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manshur, Fadlil Munawwar, and Husni Husni. 2020. Promoting Religious Moderation Through Literary-Based Learning: A Quasi-Experimental Study. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology 29: 5849–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mccaffery, Kirsten, Jane Wardle, and Jo Waller. 2003. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intentions about the Early Detection Of Colorectal Cancer in the United Kingdom. Preventive Medicine 36: 525–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, Ilma Savira, Sri Daryanti, and Alia Rachma Ningtias. 2019. The Influence Of Knowledge And Religiosity With Mediation of Attitude Toward The Intention of Repurchasing Halal Cosmetics. Paper present at the 12th International Conference on Business And Management Research (Icbmr 2018), Bali, Indonesia, November 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramadhan, Jelang, and Muhamad Syauqillah. 2018. An Order to Build the Resilience in the Muslim World Against Islamophobia: The Advantage of Bogor Message in Diplomacy World & Islamic Studies. Jurnal Middle East and Islamic Studies 5: 22. [Google Scholar]

- Ramayah, Thurasamy, Jason Wai Chow Lee, and Shuwen Lim. 2012. Sustaining The Environment Through Recycling: An Empirical Study. Journal of Environmental Management 102: 141–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riniti Rahayu, Luh, and Putu Surya Wedra Lesmana. 2020. Potensi Peran Perempuan Dalam Mewujudkan Moderasi Beragama Di Indonesia. [Women’s Potential Contribution to Religious Moderation in Indonesia]. Pustaka: Jurnal Ilmu-Ilmu Budaya 20: 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamah, Nur, Muhammad Arief Nugroho, and Puspo Nugroho. 2020. Upaya Menyemai Moderasi Beragama Mahasiswa Iain Kudus Melalui Paradigma Ilmu Islam Terapan. [Using the paradigm of Applied Islamic Sciences, efforts to sow religious moderation among other Kudus students]. Quality 8: 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, Vassilis. 2011. Believing, Bonding, Behaving, and Belonging: The Big Four Religious Dimensions and Cultural Variation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42: 1320–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwedler, Jillian. 2013. Islamists in Power? Inclusion, Moderation, and the Arab Uprisings. Middle East Development Journal 5: 1350006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartawan, Budi. 2021. Wawasan Al-Quran Tentang Moderasi Beragama. [Insights from the Quran on Religious Moderation]. Jurnal Kajian Ilmu Al-Qur’an Dan Tafsir 1: 50–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sulung, Liyu Adhi Kasari, Niken Iwani Surya Putri, Muhammad Miqdad Robbani, and Kirana Rukmayuninda Ririh. 2020. Religion, Attitude, and Entrepreneurial Intention in Indonesia. The Southeast Asian Journal of Management 14: 44–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sutrisno, Edy. 2019. Aktualisasi Moderasi Beragama Di Lembaga Pendidikan. [Religious Moderation in Educational Institutions as a Reality]. Jurnal Bimas Islam 12: 323–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ulinnuha, Muhammad, and Mamluatun Nafisah. 2020. Moderasi Beragama Perspektif Hasbi Ash-Shiddieqy, Hamka, Dan Quraish Shihab. [Hasbi Ash-Shiddieqy, Hamka, and Quraish Shihab’s Perspectives on Religious Moderation]. Suhuf 13: 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbos, Gary R., ed. 2015. Apa Dictionary of Psychology, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Joshua T. 2012. Beyond Moderation: Dynamics of Political Islam In Pakistan. Contemporary South Asia 20: 179–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibisono, Susilo, Winnifred R. Louis, and Jolanda Jetten. 2019. A Multidimensional Analysis of Religious Extremism. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, Gregory C. R., and Margaret Chandler. 1991. The Cognitive Psychology of Knowledge: Basic Research Findings And Educational Implications. Australian Journal of Education 35: 131–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuhriah, Antik Milatus. 2020. Tokoh Agama Dalam Pendidikan Toleransi Beragama Di Kabupaten Lumajang. [Religious Leaders in Lumajang Regency Teaching Religious Tolerance]. Tarbiyatuna: Jurnal Pendidikan Islam 13: 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variable | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 100 | 32.8% |

| Female | 205 | 67.2% |

| Age | ||

| 17–20 | 96 | 31% |

| 21–30 | 152 | 50% |

| 31–40 | 34 | 11% |

| 41–50 | 18 | 6% |

| >50 | 5 | 2% |

| Level of education | ||

| Islamicschool | 56 | 18.4% |

| Non-Islamicschool | 47 | 15.4% |

| Islamicuniversity | 156 | 51.1% |

| Non-Islamicuniversity | 46 | 15.1% |

| Religious affiliation | ||

| Nahdhatul Ulama | 235 | 77% |

| Muhammadiyyah | 26 | 8.5% |

| Sarekat Islam | 2 | 0.7% |

| Tarbiyah Islamiyah | 12 | 3.9% |

| Thoriqoh Dasuqiyah | 1 | 0.3% |

| Salafi | 3 | 1% |

| Unaffiliated | 26 | 8.6% |

| Total | 305 | 100% |

| Item | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 0.50 | 0.05 | 9.58 | Valid |

| Item 2 | 0.51 | 0.05 | 9.61 | Valid |

| Item 3 | 0.39 | 0.06 | 6.96 | Valid |

| Item 4 | 0.74 | 0.05 | 15.21 | Valid |

| Item 5 | 0.89 | 0.04 | 20.10 | Valid |

| Item 6 | 0.83 | 0.05 | 17.84 | Valid |

| Item 7 | 0.77 | 0.05 | 16.14 | Valid |

| Item 8 | 0.88 | 0.05 | 19.25 | Valid |

| Item 9 | 0.84 | 0.05 | 18.08 | Valid |

| Item 10 | 0.86 | 0.05 | 18.60 | Valid |

| Item 11 | 0.70 | 0.05 | 14.30 | Valid |

| Item 12 | 0.84 | 0.05 | 18.00 | Valid |

| Item 13 | 0.73 | 0.05 | 14.78 | Valid |

| Item 14 | 0.81 | 0.05 | 17.28 | Valid |

| Item 15 | 0.90 | 0.04 | 20.44 | Valid |

| Item 16 | 0.82 | 0.05 | 17.19 | Valid |

| Item 17 | 0.80 | 0.05 | 17.07 | Valid |

| Item | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 0.93 | 0.04 | 21.46 | Valid |

| Item 2 | 0.96 | 0.04 | 22.5 | Valid |

| Item 3 | 0.85 | 0.05 | 18.46 | Valid |

| Item 4 | 0.32 | 0.06 | 5.56 | Valid |

| Item 5 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 6.78 | Valid |

| Item 6 | 0.33 | 0.06 | 5.89 | Valid |

| Item 7 | 0.39 | 0.06 | 6.88 | Valid |

| Item 8 | 0.61 | 0.05 | 11.56 | Valid |

| Item 9 | 0.61 | 0.05 | 11.57 | Valid |

| Item 10 | 0.28 | 0.06 | 4.96 | Valid |

| Item 11 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 4.16 | Valid |

| Item 12 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 2.49 | Valid |

| Item 13 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 3.18 | Valid |

| Item | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 0.29 | 0.06 | 4.93 | Valid |

| Item 2 | 0.68 | 0.05 | 12.89 | Valid |

| Item 3 | 0.49 | 0.06 | 8.66 | Valid |

| Item 4 | 0.58 | 0.06 | 10.57 | Valid |

| Item 5 | 0.89 | 0.05 | 18.43 | Valid |

| Item 6 | 0.83 | 0.05 | 16.62 | Valid |

| Item 7 | 0.64 | 0.06 | 11.67 | Valid |

| Item 8 | 0.29 | 0.06 | 4.93 | Valid |

| Model | R | R-Square | Adjusted R-Square | Std. Error in the Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.562 | 0.315 | 0.302 | 7.7262677 |

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Regression | 8196.656 | 6 | 1366.109 | 22.885 | 0.000 * |

| Residual | 17,789.173 | 298 | 59.695 | |||

| Total | 25,985.829 | 304 |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | t | Sig. | ||

| 1 | (Constant) | 19.639 | 3.195 | 6.147 | 0.000 | |

| Attitudes | 0.318 | 0.061 | 0.324 | 5.254 | 0.000 * | |

| Knowledge | 0.263 | 0.059 | 0.277 | 4.464 | 0.000 * | |

| Age | 0.013 | 0.057 | 0.011 | 0.225 | 0.822 | |

| Gender | 1.226 | 0.984 | 0.062 | 1.246 | 0.214 | |

| Educational background | 1.043 | 0.989 | 0.052 | 1.055 | 0.292 | |

| Religious affiliation | –0.183 | 1.051 | –0.008 | –0.174 | 0.862 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Latifa, R.; Fahri, M.; Subchi, I.; Mahida, N.F. The Intention of Becoming Religiously Moderate in Indonesian Muslims: Do Knowledge and Attitude Interfere? Religions 2022, 13, 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060540

Latifa R, Fahri M, Subchi I, Mahida NF. The Intention of Becoming Religiously Moderate in Indonesian Muslims: Do Knowledge and Attitude Interfere? Religions. 2022; 13(6):540. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060540

Chicago/Turabian StyleLatifa, Rena, Muhamad Fahri, Imam Subchi, and Naufal Fadhil Mahida. 2022. "The Intention of Becoming Religiously Moderate in Indonesian Muslims: Do Knowledge and Attitude Interfere?" Religions 13, no. 6: 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060540

APA StyleLatifa, R., Fahri, M., Subchi, I., & Mahida, N. F. (2022). The Intention of Becoming Religiously Moderate in Indonesian Muslims: Do Knowledge and Attitude Interfere? Religions, 13(6), 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060540