Abstract

The nunnery Keikōin was a powerful Buddhist institution, famous in late-medieval Japanese history for its vigorous and successful fundraising campaigns on behalf of the Grand Shrine of Ise. Much is known about the nuns’ fundraising activities, but very little is known about their religious practice. A recently discovered painting, I believe, sheds some light on this long-standing question. It depicts an elderly nun invoking the deity Uhō Dōji in the form enshrined at Kongōshōji, a temple situated at the top of Asama Mountain, to the east of Ise’s Inner Shrine. Based on several of the iconographic elements, I argue the nun portrayed in the painting is from Keikōin and that she is shown engaging in esoteric Buddhist practices related to those carried out at Kongōshōji. Comparative analysis with other paintings and the historical record has, moreover, led me to propose that the Keikōin nuns performed these esoteric practices at Ise’s Kora no tachi, the hall where young shrine maidens prepared the daily food offerings for Ise’s deities.

Keywords:

Ise shrines; Kongōshōji; Uhō Dōji; Keikōin; esoteric Buddhism; Shingon; kora; Kora no tachi 1. Introduction

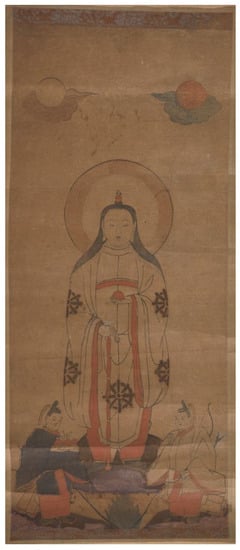

An aged nun wearing a luxurious gold brocaded kesa is depicted in profile kneeling on a ground of white pebble stones (Figure 1). She appears as if in a trance, looking towards a large emanation of Uhō Dōji 雨宝童子 (Rain Treasure Child), whom she invokes with the closed-stupa mudra (heitō-in 閉塔印). Uhō Dōji manifests in the form enshrined at Kongōshōji temple 金剛證寺, as a child with long black hair, balancing a five-wheeled stupa (gorintō 五輪塔) on its head, and holding a wish-fulfilling jewel (nyoi hōju 如意宝珠) in its left hand and a jeweled staff (hōbō) in its right. A white jewel sparkles on the deity’s forehead, a dharma wheel (rinpō 輪宝) rests on its hairline. The deity wears shoes and a white robe patterned with red and gold dharma wheels. A large pine and plum tree frame the two figures. The sun and moon rest on auspicious clouds above; a wish-fulfilling jewel perched on a pillow of golden clouds floats between them.

Figure 1.

Keikōin Nun and Uhō Dōji, Edo period, 17th century, hanging scroll, ink and colors on paper, 34 × 81 cm. Gakushūin University, Tokyo.

As will be argued in the following pages, this painting, which came to light at an auction in 2014 and is now in the collection of Gakushūin University, tells us an enormous amount about the religious history of late-medieval Ise, an area in present-day Mie prefecture that serves as the location for the Grand Shrine of Ise 伊勢神宮.1 The late-medieval history of this area has remained obscure due to critical gaps in the archival record. When read with and against the textual record, this painting fills in some of these gaps by offering a rare view of kami-Buddhist combinatory practices, women’s power, and esoteric Buddhist rituals and networks at and around Ise during this crucial period in the site’s history.

Now considered the Shinto site par excellence and a place of perfect purity, the Grand Shrine of Ise is where the tutelary deities of Japan’s imperial house are enshrined. While the shrine itself is old, these ideas of “Shinto purity”—a Shinto untarnished by external influences—are quite recent, dating to the shrine-temple separation edicts (shinbutsu bunri 神仏分離) of the Meiji government (1868–1912). Such ideas were not part of the religious mind of medieval Japan, which saw no sharp dividing line between the local, animistic worldview of the kami-worshiping tradition that later was codified as Shinto and the teeming world of buddhas and boddhisattvas that reached Japan in the sixth century. Over time, the two religious views and their respective deities merged and were intertwined, a phenomenon referred to by the neologism honji suijaku 本地垂迹 (“buddhas as original ground and local deities as manifest trace”).2

This syncretic worldview was even produced at the imperial shrines of Ise, the sacred site which arguably has had the most complicated and contentious relationship with Buddhism. Numerous Buddhist temples were established in Uji and Yamada, the towns that served the shrines, and Ise’s clergy would often take the tonsure and retire to one of these nearby temples upon completion of their shrine duties ().3 The hereditary lineages of Ise shrine priests—Watarai, Arakida, and Ōnakatomi—established family temples (ujidera 氏寺) near the shrines and from at least the mid-twelfth century they buried Buddhist sutras on Asama Mountain. Moreover, it was the fundraising efforts of Buddhist monastics that led to the rebuilding of the shrines and their surroundings in the late sixteenth century, and the subsequent revival of the shrines’ vicennial renewal (shikinen sengū 式年遷宮), after more than a century of neglect and deterioration that was the consequence of the long, internecine wars.

As important as the activities of Buddhist monastics were at Ise, our understanding of the links between the Buddhist community and the Ise shrines remains woefully incomplete. The most active and successful of these fundraising monastics was a group of nuns based in Keikōin 慶光院. The archival record of the nuns’ achievements on behalf of the Ise shrines is lively and detailed, but it is relatively silent on the nuns’ Buddhist faith and worship. We know more about Kongōshōji, another important Buddhist temple in the Ise area that aligned itself with the shrines by identifying one of its protector deities, Uhō Dōji, as the Buddhist essence (honji本地) of Amaterasu天照, the ancestral kami enshrined in Ise’s Naikū 内宮 (Inner Shrine). However, little textual evidence exists of the relationship between the two temples.

Another institution that may have played a role in the relationship between these two temples is Ise’s Kora no tachi 子良館, the hall where shrine maidens (kora子良) prepared the food offerings for Ise’s kami. By welcoming and even engaging in Buddhist practice on Ise’s sacred precincts, the kora served as a link between the Buddhist community and the Ise shrines. No record exists, however, on the relationship between the Kora no tachi and Keikōin or Kongōshōji. Understanding these relationships may offer a better understanding of the complex web of connections, reciprocal influences, economic interests, and priorities of the varied and numerous religious institutions active in Ise during the late-medieval period.

The painting of the elderly nun in contemplation before an emanation of Kongōshōji’s Uhō Dōji (Figure 1) sheds new light on these issues. Her gold embroidered kesa, a sign of rank and status, together with the painting’s combination of iconographic elements, have led me to conclude that the woman depicted is a Keikōin nun. This unique painting is of great artistic and historical interest, providing visual hints about the nuns’ religious practices and the intricately woven net of religious life at Ise in the late 16th and 17th centuries. Combining iconography specific to Kongōshōji, Keikōin, and the Ise Shrines, the painting offers a visual connection between these religious sites as well as evidence for esoteric Buddhist practice on Ise’s sacred grounds.

I will use the painting as a primary source to shine a light on the combined Shinto-Buddhist faith and practice that developed around medieval Ise and will show that the painting depicts a combinatory system of faith that originated at Kongōshōji and spread widely from the medieval to the modern period. More specifically, the iconography of the painting, together with a number of visual and textual records, lead me to conclude that the Keikōin nuns were engaged in esoteric Buddhist practices related to those at Kongōshōji, and that they may have carried out esoteric rituals on Ise’s sacred grounds, at the Naikū Kora no tachi.

I will begin with a brief historical and religious background of the three institutions at the center of this story: Ise, Keikōin, and Kongōshōji. This will set the stage for the iconographical analysis of the Gakushūin painting that follows. I will end with a discussion of Buddhism at Ise’s Kora no tachi, considering in particular the relationship of this hall and its young residents to Keikōin.

2. Situating Ise—The Shrines, Keikōin, and Kongōshōji

The term “Grand Shrine of Ise” refers to a vast institution of shrines spread across the landscape around the eastern side of the Kii peninsula in present day Mie prefecture. It consists of two principal shrines, the Naikū 内宮 (Inner Shrine or Kōdaijingū), devoted to Amaterasu Ōmikami 天照大神, the Sun Goddess and legendary ancestor of the imperial family, and the Gekū 外宮 (Outer Shrine or Toyouke daijingū), devoted to Toyouke Ōmikami 豊受大神, the goddess of food and harvest. The two principal shrines are surrounded by more than 120 subordinate shrines (massha) and auxiliary shrines (betsugū).

Since the late seventh century, the Ise shrines have been rebuilt (ideally) every twenty years in a ceremony called the shikinen sengū (abbreviated as sengū) ().4 The reconstruction of Ise’s two principal shrines and fourteen auxiliary shrines takes place on adjacent plots of land. Once the new shrines are complete, shrine priests carry out a ritual transfer of the kami from the old sites to the new; the old shrines are then dismantled, and the land is left vacant. There are a number of explanations for this practice, all based on the idea of Ise as the homeland of Japan’s native religion, Shinto, and the locus of the utmost purity that requires periodic renewal to ensure its untarnished state.5 Traditionally, either the imperial household or a military government has provided the funds for Ise’s sengū.6 Only one major interruption occurred, during the civil wars of the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when the ruling powers were bankrupted and the shrines forced to seek new sources of patronage from among the commoner classes. They did so by empowering Buddhist monastics to crisscross the country raising funds on their behalf. The most committed and effective of these fundraising monastics (kanjin hijiri 勧進聖) came from the nunnery Keikōin. The Keikōin nuns spearheaded numerous campaigns that restored Ise’s grounds and revived its vicennial sengū in the late sixteenth century.

Sources describe Keikōin as an independent Rinzai Zen sect temple based in Uji Uradachō, a town that served the Naikū. In the medieval period, Keikōin’s grounds consisted of a small Daijingū shrine and a Benzaiten kokuya 穀屋 (fundraising hall), where the nuns prayed for peace and distributed amulets (the nuns also lived in the kokuya).7 The temple had no principal image (honzon 本尊), no sutras, no Buddhist implements, and nuns who did not recite sutras (; ; ; ).8 According to Hamaguchi, Keikōin did not fulfill the mission of a Zen temple—it did not have a dharma banner (hōdō 法幢) or disciples, and it did not spread the doctrine of salvation and enlightenment ().9

According to temple lore, Keikōin was founded by the second daughter of Emperor Godaigo (r. 1318–1339), Princess Sachiko (b. ~1316–1319), a figure who is best known as Ise’s last Consecrated Imperial Princess (saiō斎王). The saiō were unmarried princesses chosen by divination when a new emperor came to power to serve as a kind of “vestal virgin” representing the Imperial House at Ise Shrine ceremonies. In 1333, Sachiko was chosen to be saiō, but after completing three years of ritual purification, political turmoil led to Godaigo’s exile and Sachiko was forced to abandon her position (). She took the tonsure with the Buddhist name Shūtoku 周徳 and went to live in a temple in Kumano, an area not far from Ise that is famous in medieval history for the ambitious kanjin 勧進 (fundraising) campaigns of the Kumano nuns (Kumano bikuni).10 Later, Shūtoku moved to Ise and established Keikōin, where she became an active fundraiser for the shrines, successfully leading a campaign to rebuild Uji Bridge in 1376—the bridge had been in such a dilapidated state that pilgrims were unable to visit the Naikū ().

Keikōin’s historical record is silent for the next eighty years, until the appearance in the late fifteenth century of Shuetsu 守悦who, same as Shūtoku, descended from the Kyoto nobility.11 She too was an energetic fundraiser and traveled around the country raising money for the Ise shrines. Shuetsu was assisted in her efforts by the head priest of the Naikū, who provided her with an official letter to use as evidence that her kanjin was approved by the shrines. Her kanjin led to the rebuilding of Uji Bridge in 1491 and again in 1504 after it was washed away in a series of floods (; ).

The Keikōin nuns continued fundraising on behalf of the shrines, rebuilding Uji Bridge again in 1545 and restoring the Gekū in 1563—one-hundred-twenty-nine years after its last reconstruction. In 1585, the nuns succeeded in rebuilding both shrines, achieving the first shikinen sengū in nearly two-hundred years. In recognition of their achievements, the Keikōin nuns received the imperial name shōnin 上人 (saint) directly from the emperor and were permitted to wear purple robes, the imperial color (; ; ). They were also the only Buddhist clergy allowed to worship within Ise shrine fences (naiin) during the sengū (; ; ).12 Though kanjin for Ise’s sengū was no longer necessary after the establishment of the Tokugawa government, Keikōin was so deeply tied to the sengū that it remained in charge of Ise’s rebuilding process.13 The Keikōin nuns no longer participated in the sengū after 1669, but their exclusive privilege of worshiping within Ise’s shrine fences during the sengū continued until 1769, and they remained a powerful presence around Ise until the Meiji period (; ; ).

While the historical record of Keikōin’s achievements on behalf of the shrines is abundant, it is comparatively slim on the nuns’ Buddhist practice. Sources simply state that Keikōin was a Rinzai Zen temple with no main or branch temple affiliations. Despite the official Rinzai affiliation, the iconography of the Gakushūin painting suggests that the Keikōin nuns engaged in esoteric practices related to those carried out at Kongōshōji, another nominally Rinzai Zen temple with Shingon origins located at the top of Asama Mountain to the east of the Naikū.14 As mentioned, the nun in the painting is shown visualizing Kongōshōji’s Uhō Dōji. This deity was identified by Kongōshōji’s Shingon proponents as the Buddhist essence of the kami enshrined in the Naikū, the imperial ancestress Amaterasu. Originating at Kongōshōji, this form of combinatory faith spread widely in the Muromachi period. I will now introduce Kongōshōji, providing a detailed description of its legendary history, ritual practice, and enshrined deities, focusing in particular on the origins and development of the temple’s Uhō Dōji faith. This background will help us better understand the complex and layered iconography of the Gakushūin painting.

According to legend, Kongōshōji was established during the reign of Emperor Kinmei 欽明帝 (r. 539–571) when a monk named Kyōtai Shōnin 暁台上人 built a hermitage on Asama Mountain where he performed the Morning Star Meditation (Kokūzō bosatsu Gumonji-hō 虚空蔵菩薩求聞持法), an esoteric ritual centered on the star Venus (Myōjō 明星) and the bodhisattva Kokūzō 虚空蔵 (; ; ).15 In this first iteration the temple was called Venus Hall (Myōjōdō 明星堂) ().16 According to the Asama dake giki 朝熊岳儀軌 (Ritual Procedures of Asama Mountain; written in the Muromachi period, between 1394–1449), the temple was restored and renamed Kongōshōji in the early ninth century by Kūkai 空海 (also known as Kōbō Daishi 弘法大師, 774–835), the founder of the esoteric Shingon sect 真言宗 ().17 The giki relates that in 825 Kūkai was performing the Morning Star Meditation on Myōjō Rock at Zenkonji temple in Nara, when just before sunrise a dōji 童子—a child guardian of the Buddhist dharma—descended from the heavens and offered to show Kūkai a spot on Asama Mountain where he would be able to successfully complete the ritual (). When Kūkai arrived at Asama he received another message, this time from the mountain’s kami, to carry out the Morning Star Meditation there. Upon completing the ritual, a nobleman appeared and guided Kūkai to Amaterasu (). She told him that Asama Mountain was the place where the kami first descended, as well as where Venus (Myōjō) appeared surrounded by the light of a dharma wheel and then transformed into the bodhisattva Kokūzō.18 Kokūzō was then enshrined in a temple on the mountain. Amaterasu lamented that the temple had been destroyed during the reign of the fifty-second emperor. Ever since Amaterasu and another kami, Ame no koyane no Mikoto, manifested at Asama every day waiting for the temple to be rebuilt. Amaterasu implored Kūkai to rebuild the temple and to carry out Shingon Buddhist rituals on Asama Mountain, explaining that this was the only way the kami would protect the realm in the future. Amaterasu then made Uhō Dōji the protector of Asama Mountain and those who performed the Morning Star Meditation; in return, Amaterasu told him, practitioners must worship Uhō Dōji ().

In the 1614 Asama dake engi 朝熊岳縁起 (Karmic Origins of Mount Asama), written by the Kongōshōji monk Meisō 明叟, we are told that the temple was rebuilt and converted in 1392 to Rinzai Zen under the Kenchōji temple monk Tōgaku Buniku東岳文昱, who, as with Kūkai, did so based on an oracle from Amaterasu, which he received during an Ise pilgrimage ().19 Despite its new sectarian affiliation, many of Kongōshōji’s Shingon practices were retained and its principal image remained the bodhisattva Kokūzō, an esoteric deity, attended by Myōjō tenshi 明星天子 (Venus) and Uhō Dōji. Indeed, around the time of its Zen conversion, Asama became a training site for travelling mountain ascetics (yamabushi 山伏) connected to Sanbōin三宝院, a sub-temple of the esoteric Buddhist complex Daigoji醍醐寺, southwest of Kyoto (). Moreover, at this time, we begin to see Sanbōin-related Shugendō practices at Kongōshōji, which were increasingly influenced by Ryōbu Shintō 両部神道 (“Shinto of the Two Worlds Mandalas”), a combinatory system developed by Shingon monks in the twelfth century that was based on the association of the Naikū and Gekū with the Taizōkai 胎蔵界 (Womb World) and Kongōkai金剛界 (Diamond World) mandalas ().

According to Nishida Nagao, after the temple’s conversion, the Shingon faction that remained at Kongōshōji was in conflict with the temple’s Zen faction (). Meanwhile, until the early fifteenth century, Uhō Dōji had remained in a relatively minor, supportive role as guardian of Asama and attendant to Kongōshōji’s principal image, Kokūzō (). Around this time, however, Uhō Dōji was elevated in status to emanation of Amaterasu and Kokūzō (; ). Nishida believes Uhō Dōji faith was invented by Kongōshōji’s Shingon Ryōbu Shintō proponents between 1419–1428 and that they wrote the Asama dake giki to assert their interests at the temple ().

In the giki we are told that Amaterasu stroked the head of Sekisei Dōji (Uhō Dōji) and blew out a five jewel (stupa) (gorin), which she placed on the dōji’s head, and Kokūzō blew out a golden wish-fulfilling jewel (nyoi hojū) and placed it on the dōji’s forehead.20 The bodhisattva Jizō then emerged from the dōji’s red wish-fulling jewel and preached salvation from the six paths. From the dōji’s jeweled staff (hōbō) Venus emerged and recited a verse about growth and prosperity. Bernard Faure observed that the cult of Uhō Dōji established in the giki, “reflects (and allows) the transition from Kokūzō to Amaterasu, and from Asama to Ise” (). Through Uhō Dōji the giki thus forged the link between Kokūzō/Asama and Amaterasu/Ise and established the basis for the focus on Uhō Dōji at Kongōshōji from the fifteenth century on.

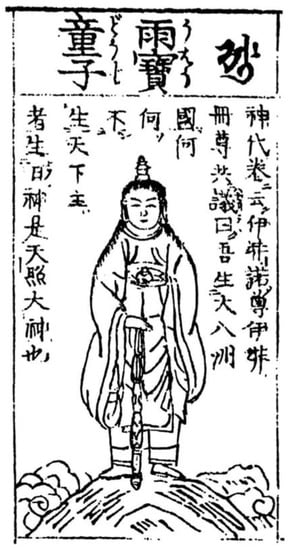

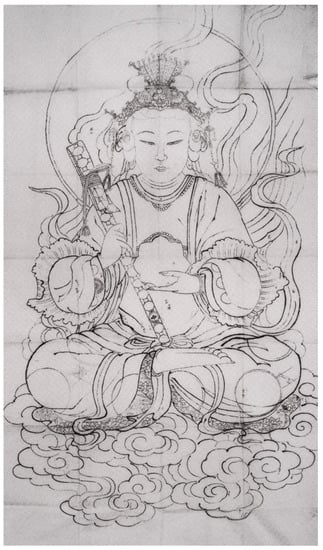

The identification of Uhō Dōji as Amaterasu’s original essence (honji) became increasingly popular from the late Muromachi period; shrines dedicated to this manifestation of Amaterasu were established throughout Japan and images of Amaterasu as Uhō Dōji proliferated ().21 A Heian period sculpture of Uhō Dōji housed at Kongōshōji served as the model for many of the images that circulated at this time.22 The sculpture follows closely the deity’s description in the giki (Figure 2). Carved from a single block of Japanese cypress, the figure stands on a mountainous rock, wearing a plain, long-sleeved robe and shoes, holding a wish-granting jewel in its left hand and a jeweled staff in its right. Its straight hair flows past its shoulders, and on top of its head rests the esoteric Buddhist symbol of the five elements, the gorintō.23 According to temple tradition, Kūkai carved this sculpture after Amaterasu manifested before him as a 16-year-old dōji (; ). In other words, Amaterasu was worshiped at Kongōshōji in the form of Uhō Dōji.

Figure 2.

Uhō Dōji, Heian Period, Cypress wood, 102 cm. Kongōshōji, Ise City. Reproduced with permission from (). Copyright 2016 University of Hawai‘i Press.

Kongōshōji thus connected itself to the Ise shrines through the identification of Uhō Dōji as Amaterasu’s original essence. Although this led to occasional conflicts with the shrines, as early as the Muromachi period we see evidence of Kongōshōji becoming part of a “three-shrine pilgrimage” (sangū mairi), together with the Naikū and Gekū. By the early Edo period the link between the shrines and Kongōshōji was firmly established—Ise’s onshi (low-ranking priests who spread Ise faith) brought pilgrims to the temple as part of an Ise pilgrimage (). The necessity of visiting Kongōshōji can even be found in a line from a popular Edo period folk song: “If you go on a pilgrimage to Ise, go to Asama! If you don’t go to Asama, your pilgrimage is incomplete”.24

As this discussion has shown, Kongōshōji and Keikōin were, in very different ways, closely tied to the Ise shrines during the medieval and early modern periods—at Kongōshōji, the connection was made through the identification of the temple’s Uhō Dōji as the original essence of Amaterasu, the imperial kami enshrined in Ise’s Naikū; at Keikōin the connection to Ise was forged by the fundraising campaigns carried out by the Keikōin nuns on behalf of the shrines. However, as mentioned, the historical record is relatively silent on the relationship between Kongōshōji and Keikōin, as well as on the Buddhist practice of the Keikōin nuns. For this reason, the painting recently acquired by Gakushūin University (Figure 1) is of great historical significance for the light it sheds on this lacuna, providing strong evidence for the form of Buddhist worship at Keikōin, and tying the nuns’ practice to both Kongōshōji and the Ise shrines.

3. Keikōin Nun and Uhō Dōji Painting: Iconographic Analysis

An elderly nun kneels on a ground of white pebbles and forms the “closed stupa mudra” (heitō-in) to invoke the large emanation of Kongōshōji’s Uhō Dōji that appears before her (Figure 1). A large pine and plum tree elegantly frame the figures. Above, the sun and moon rest on auspicious clouds while a wish-fulfilling jewel floats on a golden cloud between them.

Based on the nun’s gold embroidered kesa and the white pebble ground on which she kneels, as well as the surrounding motifs which will be discussed in detail below, I believe the aged woman depicted in the painting is a Keikōin nun (perhaps even a specific nun, such as Shuetsu), and that she is shown visualizing Kongōshōji’s Uhō Dōji, the original essence of Amaterasu, the sun goddess and imperial ancestress enshrined in the Naikū. While the luxurious kesa points to the Keikōin nuns’ aristocratic origins, the stones, suggestive of the river-washed pebbles surrounding the Naikū and Gekū, may refer to the privileged status of the nuns, the only Buddhist clergy allowed within shrine grounds during Ise’s sengū. These pictorial elements alone draw a connection between Keikōin (the nun), Kongōshōji (Uhō Dōji), and the Ise shrines (Amaterasu as Uhō Dōji).

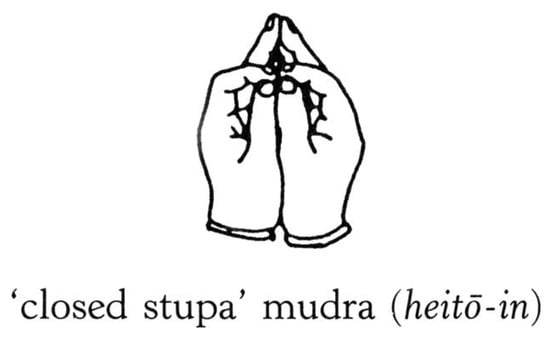

The connection is further reflected in the nun’s mudra, heitō-in (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Initiations, known as kanjō 灌頂in esoteric kami practice, are secret formulas transmitted from master to disciple, consisting of a mudra, a mantra, and an accompanying visualization ().25 The first step of the Ise kanjō, carried out at the gate (torii) of a shrine, calls for the practitioner to form the heitō-in while vocalizing the syllable a. This mudra and mantra represent the Taizōkai 胎蔵界, or Womb World, of the cosmic Buddha Dainichi’s 大日如来 compassion (). In Ryōbu Shintō, the Taizōkai is identified with Amaterasu, the Naikū, and the sun; Uhō Dōji is also identified with Amaterasu in Ryōbu Shintō ().26

Figure 3.

Keikōin Nun and Uhō Dōji, Edo period, 17th century, hanging scroll, ink and colors on paper, 34 × 81 cm. Gakushūin University, Tokyo. Detail of mudra.

Figure 4.

Heitō-in mudra. Reproduced from Inaya Yūsen, Shingon Shintō shūsei; Seizansha, 1993.

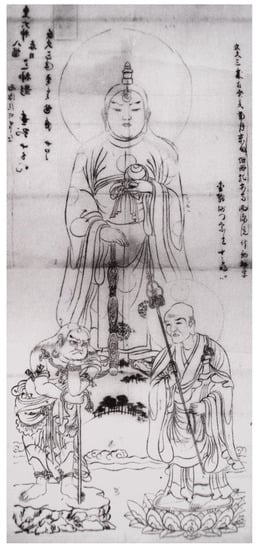

Visual evidence of this teaching and its popularity can be found in an Edo period woodblock print showing Kongōshōji’s Uhō Dōji with the seed syllable of Dainichi of the Taizōkai, āḥ. The text surrounding Uhō Dōji, moreover, refers directly to Amaterasu (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Woodblock print of Uhō Dōji from the Sanjūbanjin (Thirty Deities) series. Edo period. (Image courtesy of Brian ()).

It seems likely, therefore, that the accompanying visualization for the heitō-in would be Amaterasu or one of her Buddhist manifestations. As Amaterasu’s original essence, Uhō Dōji was understood to be equivalent to Amaterasu and thus an appropriate visualization for the heitō-in. We see this represented in the Gakushūin painting: the nun forms the heitō-in and invokes Amaterasu in the form of Kongōshōji’s Uhō Dōji. As Toba Shigehiro and others have shown, this imagery would not have been unusual, countless representations in the Edo period depict Amaterasu as Uhō Dōji (Figure 6 and Figure 7) (; ; ).

Figure 6.

Sanja takusen, Edo period, hanging scroll, ink and colors on paper, 54.6 × 23.5 cm. Author’s collection.

Figure 7.

Uhō Dōji (also known as Sanja Gongen; Manifestations of the Three Shrines), Edo period, sheet, ink on paper. University Art Museum, Kyoto City University of Arts. Reproduced with permission from (). Copyright 2016 University of Hawai‘i Press.

Moreover, Edo period sanja takusen (‘The Oracles of the Three Shrines’) scrolls, which represent Amaterasu in the form of Kongōshōji’s Uhō Dōji, decorate Amaterasu’s robe with the same dharma wheels as those on Uhō Dōji’s robe in the Gakushūin painting (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

The sun, moon, and wish-granting jewel at the top of the painting form further points of connection between Kongōshōji, Keikōin, and the Ise shrines. On one level, the sun and moon symbolize Amaterasu/Naikū and Toyouke/Gekū, respectively. Together, they also may be understood as Uhō Dōji, who was identified in a Ryōbu Shintō text, the Uhō Dōji keibyaku 雨法童子啓白, as the true form of both the sun and moon.27 More generally, as in other Buddhist images, the sun and moon infuse the painting with an atmosphere of otherworldly timelessness.

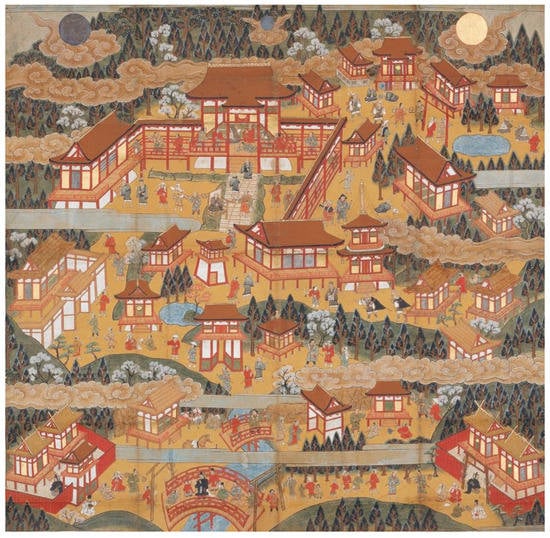

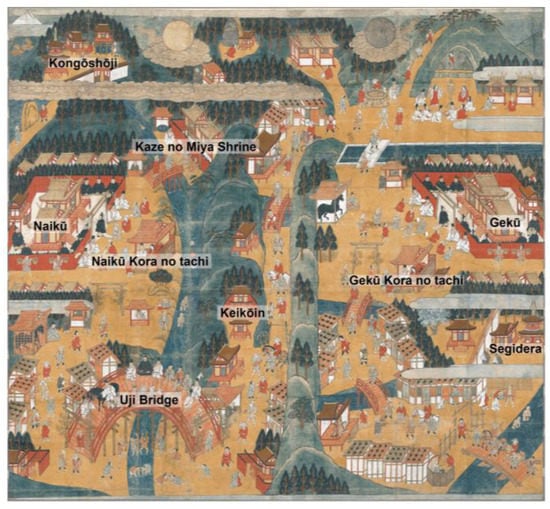

The addition of a wish-granting jewel between the sun and moon is an iconographical arrangement pointing to Kongōshōji. The same arrangement of motifs, with Venus (Myōjō) in place of the wish-granting jewel, appears at the top of the seventeenth century Kongōshōji Ise Pilgrimage Mandala (Kongōshōji Ise sankei mandara; Figure 8).28

Figure 8.

Kongōshōji Ise Pilgrimage Mandala, early 17th century, hanging scroll, ink and colors on paper. 146.2 × 150.4 cm. Yoshiminedera, Kyoto.

While the majority of pilgrimage mandalas depict the sun and moon, only the Kongōshōji Ise Pilgrimage Mandala includes this third iconographical component, which refers to Kongōshōji’s origins in Kokūzō and the Morning Star Meditation—Kokūzō is identified with Venus (Myōjō), and both deities are at the center of the ritual.29 The symbolic form (sammaya) of Kokūzō, moreover, is the wish-granting jewel. During the Morning Star Meditation the practitioner forms and recites only the wish-granting jewel mudra and mantra ().30 We may therefore think of Kokūzō, Venus (Myōjō), and the wish-granting jewel as being equivalent and interchangeable in medieval esoteric thought and iconography (). Amaterasu came to be incorporated into this Buddhist system and by the fourteenth century was commonly equated with the wish-granting jewel (Figure 9).31

Figure 9.

Amaterasu (Tenshō Daijin), Edo period, woodblock print, ink on paper. University Art Museum, Kyoto City University of Arts. Reproduced with permission from (). Copyright 2016 University of Hawai‘i Press.

Lastly, the combination of sun, moon, and wish-granting jewel at the top of the painting might carry an additional reference to Kūkai, the legendary founder of Kongōshōji. Drawings of Kūkai from the fourteenth century show him seated below a wish-granting jewel flanked by the sun and moon (Figure 10). According to Lucia Dolce, the wish-granting jewel in these drawings symbolizes Venus (Myōjō) and Kokūzō (). Moreover, Bernard Faure argues that the point of these drawings was to identify Kūkai with the wish-granting jewel (). The wish-granting jewel in the Gakushūin painting is thus endowed with several layers of meaning, simultaneously signifying Venus (Myōjō), Kokūzō, Amaterasu, and Kūkai, and by extension Kongōshōji and the Ise shrines. Its inclusion in the Gakushūin painting and its position between the sun and moon further links the Keikōin nun’s religious practice with Kongōshōji. Finally, the placement of the wish-granting jewel in the highest position of the painting is meaningful. In Japanese religious landscape painting, compositional space is arranged vertically according to relative sacredness, with motifs in the lower regions of the painting considered less sacred than those in the uppermost regions.32 We should therefore understand the wish-granting jewel to be the most sacred element of the Gakushūin painting.

Figure 10.

Kūkai with Jewels and Dragons, 14th century, color on paper. Ninnaji, Kyoto. Reproduced with permission from (). Copyright 2016 University of Hawai‘i Press.

The pine and plum tree, which figure prominently in the Gakushūin painting, are motifs with a long history of symbolic and seasonal associations in East Asian art, variously associated with winter, strength, longevity, steadfastness, courage, perseverance, and hope. The fragmented forms of the trees and the way they curve over and frame the central figures is a common visual device of East Asian painting. However, the inclusion of pine and plum in a religious painting with so few iconographic elements suggest these trees carry symbolic meaning beyond such generic associations.

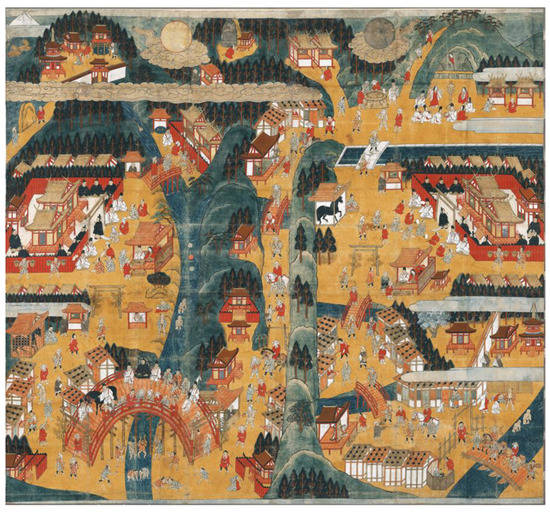

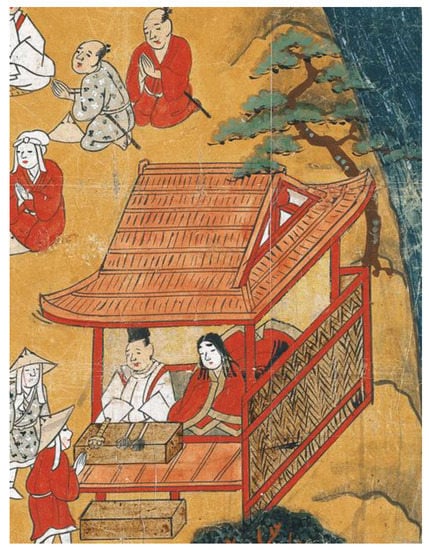

Although only the upper portion of the pine is visible, its twisted trunk and arc-shaped boughs are striking. A pine of similar form is depicted in the Jingū Chōkokan Ise Pilgrimage Mandala (Ise sankei mandara; Figure 11), a painting that was commissioned by the Keikōin nuns. In the mandala, the pine extends over the Naikū Kora no tachi, the hall where the young kora prepared food offerings for Ise’s kami (Figure 12, detail of Figure 11 and Figure 13). Although there are many other pine trees depicted in the mandala, the one behind the Naikū Kora no tachi is distinctive in size, form, and color, and its upper section is a mirror image, nearly identical to the Gakushūin pine. Moreover, lichen grows on the trunks of both pines, an inclusion not found on any of the other pine trees in the Ise Pilgrimage Mandala. Comparing this depiction of the Naikū Kora no tachi with its depictions in the other two extant Ise Pilgrimage Mandalas, paintings not commissioned by the Keikōin nuns, we find the hall without a pine tree framing it (Figure 14 and Figure 15).33 This suggests the Naikū Kora no tachi, or the area just behind it, was of particular significance to the Keikōin nuns and further suggests that the pine in the Gakushūin painting, which I believe shows the same tree viewed from the opposite side of the Kora no tachi, depicts the same location and is thus imbued with a corresponding significance.

Figure 11.

Ise Pilgrimage Mandala, late 16th century, hanging scroll, ink and colors on paper, 67 ½ × 73 ¼ in. (171.4 × 186 cm). Jingū Chōkokan Museum, Mie Prefecture, Japan.

Figure 12.

Ise Pilgrimage Mandala, late 16th century, hanging scroll, ink and colors on paper, 67 ½ × 73 ¼ in. (171.4 × 186 cm). Jingū Chōkokan Museum, Mie Prefecture, Japan. Detail of Naikū Kora no tachi.

Figure 13.

Labeled Ise Pilgrimage Mandala.

Figure 14.

Ise Pilgrimage Mandala, 17th century, former hanging scroll, now mounted as a two-panel folding screen, ink and colors on paper, 59 ½ × 71 in. (151.1 × 180.3 cm). Kimiko and John Powers Collection, Colorado.

Figure 15.

Ise Pilgrimage Mandala, 17th century, pair of hanging scrolls, ink and colors on paper, each 50 × 34 3/8 in (127 × 87.3 cm). Mitsui Bunko, Tokyo.

The pine may be merely a framing device to signify the sacred nature of the hall in the mandala and the nun and Uhō Dōji in the Gakushūin painting. However, it could also represent the Many-Branched Pine (Momoe no matsu 百枝松), a sacred pine on the grounds of the Naikū where pilgrims worshipped Amaterasu.34 The exact location of the Many-Branched Pine is unknown. According to an entry from 1076 in Minamoto Toshifusa’s 源俊房 Suisaki水左記, the sacred pine was in front of the Naikū.35 Several poems include lines that suggest it was located in Kamiji Yama, an area at the upper reaches of the Isuzu River, south of the Naikū.36 The Naikū Kora no tachi was also situated at the southern end of the Isuzu River, just past the Naikū’s second torii, in front of Kaze no Miya Bridge ().37 It is possible that the Many-Branched Pine, or a similarly large sacred pine, was located behind the Kora no tachi, towards Kaze no Miya Bridge. The entry for the Naikū Kora no tachi in the Ise sangū meisho zue includes a poem, presumably about the Kora no tachi, that mentions a grove of pine trees ().

There is less visual and archival evidence to aid in identifying the plum tree in the Gakushūin painting, but a poem by Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694) suggests that it too points to the Naikū Kora no tachi. When Bashō visited Ise in 1688 he was shocked to find not a single plum tree on Ise’s grounds. He approached an Ise priest to inquire how this could be and was told that Ise’s only plum tree could be found behind the Kora no tachi. Inspired, Bashō wrote the following haiku: “How befitting it is, for holy virgins, a solitary stock of fragrant plum”.38

Based on the visual and textual evidence, I believe the Keikōin nun is shown in contemplation on or near the grounds of the Naikū Kora no tachi. Pines are much longer-lived trees than plums so the absence of the plum in the Jingū Chōkokan Ise Pilgrimage Mandala, which dates to the late sixteenth century, might further suggest a seventeenth century date for the Gakushūin painting. However, we still need to understand the significance of Ise’s kora and the Kora no tachi to Keikōin and the larger Buddhist community. Why are the Naikū and Gekū Kora no tachi so prominently depicted in all three Ise Pilgrimage Mandalas, paintings that were commissioned by itinerant Buddhist monastics to aid in fundraising campaigns for the shrines? In the following sections I will attempt to address these questions raised from the iconographic analysis and will seek the answer in the activities of the kora, which were heavily influenced by esoteric Buddhist doctrine and practices.

4. Buddhism and the Kora No Tachi

The Naikū and Gekū Kora no tachi served as the residence halls of the kora, the shrine maidens who prepared and carried out the ritual food offerings to Ise’s kami. Among the many priests who served Ise’s kami, only the head kora (okorago 御子良子) held the key to Ise’s most sacred halls, and she alone was permitted inside Ise’s daily food offering hall (Mikedono 御饌殿) (; ).39 Because she had the most intimate access to Ise’s deities, the okorago had to remain in a state of absolute purity and was therefore the only one among Ise’s ritualists who was never to leave shrine grounds ().

The historical archive on the kora and the Kora no tachi is scant, due in large part to the secretive nature of the orally transmitted rituals of the kora, but it suggests that, contrary to the official position of the Shrine, Buddhism and its practitioners were welcomed at the Kora no tachi. The Shingon monk Tsūkai 通海 (late 13th c.?), for example, writes in his Tsūkai Daijingū sankeiki 通海大神宮参詣記 (Records of Pilgrimage to the Ise Grand Shrine) that there was an enormous tree in front of the Naikū Kora no tachi under which monks and lay people would gather and converse (; ). In the Genkō Shakusho元亨釈書, the Zen monk Kokan Shiren 虎関師錬 (1278–1346) describes being stopped under a huge tree by a Naikū priest and told he was not allowed to go any further because Ise’s kami hated monks (). The tree, presumably the same as the one described by Tsūkai, apparently served as the boundary line (genkaiten 限界点) for monastics; a cedar tree served this function on the side of the Gekū.40 It is doubtful that the large tree described by Tsūkai and Kokan was the famous Many-Branched Pine.41 Another telling account of Buddhist proclivities at the Kora no tachi comes from the monk Hasshin 発心 (mid-thirteenth century), who describes a kora interceding on his behalf when an Ise priest stopped him from approaching the Naikū. The kora told the priest that Hasshin should be permitted to proceed because the kami accepted Buddhists. Remarkably, the priest relented thanks to the young kora’s intervention ().42 Hasshin’s story is particularly revealing because it not only provides anecdotal evidence of Buddhist activity on shrine grounds, but also gives a sense of the power and influence of Ise’s kora, a point made explicit in Tsūkai’s Daijingū sankeiki where he writes that the most important role at Ise was fulfilled by the kora.43

Concrete evidence for Buddhist faith at the Kora no tachi is found in Bashō’s 1688 travel diary, in a haiku expressing surprise and delight upon encountering an image of the Buddha’s parinirvāṇa at the Gekū Kora no tachi: “What a stroke of luck, it is to see, a picture of Nirvana, in the holy Compound!” (; ).44 Moreover, Yamamoto Hiroko and Odaira Mika have shown that the kora were themselves practitioners of esoteric Buddhism, and that the ritual practice at the Kora no tachi combined elements of Shinto and Shingon (; ).45 The Gekū okorago even performed esoteric rituals in Ise’s food offering hall, during the twice daily offerings to Ise’s kami.46 Another Shingon connection may be found in the research of Miyake Hitoshi, who has found that Ise’s kora, upon completion of their duties, often married retired yamabushi (mountain ascetics) from the Shingon temple Segidera 世義寺, located in the Ise town of Yamada (; see Figure 13).

The important role played by Ise’s kora combined with the strong Shingon ties at the Kora no tachi may explain the prominent depiction of the halls on the Naikū and Gekū grounds in all three extant Ise Pilgrimage Mandalas, two of which were commissioned and used by Shingon yamabushi (Figure 14 and Figure 15).47 Still, we need to understand the nature of the relationship between Keikōin and the Naikū Kora no tachi. The Keikōin nuns would have instructed the painter of the Ise Pilgrimage Mandala they commissioned to mark the Naikū Kora no tachi with the Many-Branched Pine (or a distinctive pine tree), and the Keikōin nun in the Gakushūin painting is shown invoking Uhō Dōji on the grounds of the hall (based on our interpretation of the pine and plum). The following section will propose two theories concerning the connections between these two institutions.

5. Keikōin and the Naikū Kora No Tachi

One possible explanation for the nuns highlighting the Naikū Kora no tachi in their Ise Pilgrimage Mandala relates to Keikōin’s founder, Shūtoku, Emperor Godaigo’s daughter and Ise’s last saiō. As we know, the saiō, as with the kora, was a prepubescent girl who served Ise’s deities. The saiō only participated in Ise’s three most important seasonal rites (sansetsusai 三節際).48 During these rituals, the saiō would enter Ise’s grounds and at the western gate of the shrine’s innermost fence (mizugaki) she would hand the Naikū kora a branch hung with mulberry cloth (futo-tamagushi) to offer Ise’s kami on behalf of the imperial house (). The ritual duties of the Naikū kora were also limited to the shrine’s most important annual ceremonies, including the three seasonal rites (the Gekū kora, by contrast, was responsible for the twice daily food offerings to Amaterasu and Toyouke at the daily food offering hall—Mikedono) (). During these ceremonies, the Naikū kora presented offerings, such as the saiō’s branch hung with mulberry cloth, to Amaterasu at the foot of the Naikū’s pivot post (Shin no mihashira心御柱) ().49 Located under the floor of the Naikū shōden 正殿 (main hall), the pivot post is the center of Ise’s most sacred and exclusive hall. It is the shintai 神体 of Amaterasu, the object into which the deity descends, and only the Naikū kora was permitted before it (; ). According to Mark Teeuwen and John Breen, at a very early stage in the Shrine’s history, even before there was a proper shrine building, the saiō would have been the one to carry out rituals at the pivot post.50 It seems likely, therefore, that when the saiō system was abolished in the fourteenth century, the ritual duties of the saiō were transferred to the Naikū kora.51 Indeed, there was precedent for doing this, as recorded in the Ise Protocols of 804: “at present, it is the ōmonoimi [okorago; the head kora] rather than the abstinence princess [saiō] who approaches the Great Kami and serves her in close proximity” (; ). In addition, until the middle of the sixth century, the saiō resided in a fenced-in compound on the upper bank of the Isuzu River (as we know, this is where the Naikū Kora no tachi was situated (; )). The emphasis placed on the Naikū Kora no tachi in the Jingū Chōkokan Ise Pilgrimage Mandala could thus point to Keikōin’s historical roots and illustrious origins in the saiō. The mandala was used by the Keikōin nuns as a visual accompaniment to recitation performances (etoki 絵解き) to raise funds for the maintenance and renewal of the shrines.52 Standing before an audience, the nun would point to different areas of the painting and weave together a narrative that combined religious present and legendary past, extolling Ise’s wondrous sites and spiritual benefits, its miraculous history and its local specialties. Elevating and emphasizing Keikōin’s origins and historical ties to Ise in the saiō through the depiction of the Naikū Kora no tachi would impress the nun’s audience and give legitimacy to her plea, leading to more generous donations.53 The depiction of the Keikōin nun invoking Uhō Dōji at the Naikū Kora no tachi in the Gakushūin painting, however, suggests a spiritual connection to the hall or its residents that went beyond any immediate financial needs related to the nuns’ fundraising campaigns.

More research on the origins and nature of that spiritual connection is necessary, but one clue may be found in the historical significance of the dōji, a child guardian of the Buddhist dharma, and its relationship to the kora. With the emergence and development of Ryōbu Shintō in the medieval period, the dōji rose to prominence and became extremely influential. As Odaira Mika has shown, the dōji was equated at this time with Ise’s kora, a figure who, as we know, was also extremely influential in the medieval period and who was engaged in esoteric Shingon rituals (). Faure has observed that the term dōji, moreover, “designates both the god and the child medium possessed by the god”—so in this sense too, at medieval Ise dōji referred to the kora (). Indeed, we know from historical accounts that the kora received divine oracles from Ise’s kami, and that she would whisper divinations about the future—presumably received from the kami—as she walked from the Kora no tachi to Ise’s food offering hall (). In addition, according to Odaira, Shingon Ryōbu Shintō texts placed the kora on an equal level of importance as Ise’s pivot post. As the object into which Amaterasu descends, accessible only to the Naikū kora, it seems possible that medieval esoteric practitioners would have identified the pivot post with the kora, the child medium possessed by Amaterasu. The mutual identification of the dōji, the kora, and the pivot post may have led the Keikōin nuns to worship Amaterasu in the form of Kongōshōji’s dōji, Uhō Dōji, at the Naikū Kora no tachi, and thus the depiction of the nun invoking Uhō Dōji in the Gakushūin painting. We may never know with certainty the meaning of the iconography or the location of the nun’s worship in this painting, but I am hopeful that new visual and textual evidence will continue to emerge that will help us improve our understanding of the Keikōin nuns’ Buddhist practice and its connection to Kongōshōji and the Naikū Kora no tachi.

6. Conclusions

This paper has attempted to cast new light on an important but murky period in Ise’s religious history through the close study of an enigmatic painting of an elderly nun in contemplation which, I have argued, represents a Keikōin nun. Combined visual and textual analysis has led me to draw several conclusions about the Keikōin nuns’ Buddhist practice, something we know very little about from the historical record. I believe the nun in the Gakushūin painting is shown visualizing Amaterasu in the form of Kongōshōji’s Uhō Dōji on or near the grounds of the Naikū Kora no tachi. The Uhō Dōji faith established at Kongōshōji by its Shingon Ryōbu Shintō proponents is thus reflected in the painting, providing evidence that Keikōin, contrary to the historical sources, was not strictly a Rinzai Zen temple. It further suggests that the Keikōin nuns, as with Ise’s kora, may have engaged in esoteric Buddhist practice on Ise shrine precincts.

We are left with many questions about this unusual painting, the most basic of which is how would it have been used? It was not a primary image (honzon) nor a central focus of ritual or worship. Maybe it commemorates a vision, a dream, or even an experience of a Keikōin nun. Continued research into Keikōin and its esoteric networks, together with a close study of any related visual and textual materials that come to light, will surely yield new discoveries and interpretations. As this study of a single painting has shown, combining visual analysis with the textual record is a powerful tool, essential to obtaining a full historical understanding of Ise and of Japanese religion writ large.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This painting was lot A-062 in the 80th auction of Kogire-kai, where it was titled Ise ōkami rairin ga (伊勢大神来臨画). In the accompanying catalogue description, we are told that the box of the painting is inscribed by Matsura Hiromu (1791–1867), the 10th daimyo of Hirado. In his inscription, Matsura writes that the painting came from Nanto (Nara), and identifies the figures as Kasuga Myōjin and the monk Myōe Shōnin. Matsura’s reference to Nanto may be based on his assumption that the work was painted in the same studio as the Kumano Pilgrimage Mandalas. As the author of the Kogire-kai catalogue entry points out, the seated figure is undoubtedly a nun, so Matsura’s identification of this figure as Myōe is incorrect. The author goes on to speculate that the figures represented in the painting are a Keikōin nun and Uhō Dōji. This identification is based on the painting’s date of production, which the author believes is the early Edo period, and its correspondence with the the Keikōin nuns fundraising activities on behalf of the shrines. |

| 2 | For a detailed discussion of honji suijaku, see (). |

| 3 | In Yamada alone there were 67 Shingon temples, 34 Tendai temples, 145 Zen temples, and 50 Pure Land temples (). |

| 4 | On the reverberations of Ise’s architectural tradition in modern times as well as the shrines’ representations in text and image, see (). |

| 5 | For a thorough discussion of the changing concept of purity at Ise and the complex relationship of Ise and Buddhism, particularly how it developed during the reign of Empress Shōtoku (718–770) and her advisor, the monk Dokyō, see (). |

| 6 | Ise’s rebuilding was funded from the late eleventh century by a special tax (daijingū yakubukumai) imposed on communal and private lands throughout Japan, though political chaos from the early fifteenth century onward rendered the collection of this tax impossible (; ). |

| 7 | According to Nishiyama Masaru, Keikōin’s buildings were magnificent. From the temple the nuns distributed red printed kokuya fuda 穀屋札. Printed on the front of the fuda was Ise naikū shoganninshū kokuya 伊勢内宮諸願人衆穀屋 and impressed with a kao; on the back was written in black Benzaiten yōshuso 弁財天養首座 and impressed with a stamp (). According to Kobayashi Yukio, Keikōin’s third nun Seijun 清順 lived in a hermitage in the town of Okamoto; she was originally a Kumano nun (). |

| 8 | In the section “Ise bikuni no kōseki,” in Miko to Bukkyō-shi, Hagiwara Tatsuo writes that Keikōin had no hondō but its honzon was Shakyamuni (). |

| 9 | Kekōin began as a temple devoted exclusively to kanjin hijiri activity. Later (presumably once kanjin was no longer necessary), the nuns prayed for the welfare of the shogun and the nobility (). |

| 10 | According to Anzai Nahoko, Sachiko entered the temple Hōanji in the town of Kumano in Kyoto, though the majority of sources say she went to a temple in Kumano in the Kii peninsula (). Keikōin ki, for example, says Sachiko lived in Kii as a kanjin hijiri (; ). |

| 11 | Shuetsu was from the Asukai family, a branch of the Fujiwara (; ). |

| 12 | According to Ujiyamada-shishi, during the sengū the Keikōin nuns were permitted to worship within the Mizugaki, the shrine’s innermost fences (). |

| 13 | The Keikōin nuns were in charge of organizing the sengū until Kanbun 9 (1669) (). Ieyasu donated 30,000 koku for the Keichō 14 (1609) shikinen sengū and subsequent Tokugawa shoguns followed his example. The Keikōin nuns would receive the bakufu donation and then distribute it to the shrines (). |

| 14 | Two pieces of evidence already pointed to a relationship between Keikōin and Kongōshōji. The first is the gravestones of two of Keikōin’s head nuns, Seijun (mid-sixteenth century) and Shūyo 周養 (late sixteenth century), which are both located in Kongōshōji’s Okunonin. The second, of much later date, is that Keikōin gave Kongōshōji the Benzaiten statue enshrined in their kokuya in response to the shinbutsu bunri policy of the Meiji period (; ). I saw Seijun and Shūyo’s gravestones when I visited Kongōshōji in 2014. |

| 15 | The Gumonji-hō is an esoteric Buddhist ritual performed for perfect memory. Kyōtai also prayed at Asama for the safety and prosperity of the realm. |

| 16 | Kinmei was probably not referred to contemporaneously as Tennō (emperor); the first emperor with the title of Tennō is believed to have been Emperor Tenmu (631–686). |

| 17 | According to Nishida Nagao, the giki was written around 1448 (). |

| 18 | The Gumonji-hō involves visualization of Kokūzō in the form of Venus (Myōjō). |

| 19 | Because Tōgaku Buniku died in 1416, Tada Jitsudō believes that the engi was written by a Togakubuniku’s disciple for the purpose of fundraising. He also argues that Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, after a pilgrimage to Ise and Asama in the ninth month of 1393, saw the dilapidated state of Kongoshoji’s halls and ordered the temple to be rebuilt (). |

| 20 | The deity is formally called Kongō Sekisei Zenshin Uhō Dōji 金剛赤精善神雨法童子. |

| 21 | Kubota Osamu points out that the honji suijaku relationship between Uhō Dōji and Amaterasu is recorded in the 1614 Asama dake engi and the Uhō Dōji keibyaku, B version (). According to Nishida, Uhō Dōji faith originated at Kongōshōji and is ultimately rooted in the temple’s honzon, Kokūzō, who is identified as both the wish-granting jewel (nyoi hōju) and Myōjō Tenshi, or Venus (). In commentaries on the Lotus Sutra, Myōjō Tenshi is identified as Kokuzō (). |

| 22 | The temple Hasedera also has a statue of Uhō Dōji, which is very different in appearance than the figure at Kongōshōji. Hasedera’s Uhō Dōji was carved between 1537–1544. Adorned with a crown, its hair is styled with buns on each side of its head (mizura 角髪). It wears a red robe with a green gusset and holds a wish-fulfilling jewel in its left hand and a jeweled staff in its right. According to Toba Shigeru, the difference in appearance is due to the way Uhō Dōji is described and visualized in the origin histories of each temple. As with Kongōshōji, Hasedera issued images of its Uhō Dōji (). |

| 23 | According to John Rosenfield the gorintō “symbolizes the five physical constituents of all material matter, all living deities. The cubic base denotes the earth and often bears the Indic syllable “A”. Next is a sphere that designates water and is marked with the syllable “Vi”. The four-sided pyramidal section signifies fire and is marked with the syllable “Ra”. Above that a hemisphere denoting wind is marked by the syllable “Hūm”. The jewel shape at the top, signifying space or the void, is marked with the syllable “Kham”. The five syllables together form a-vi-ra-hūm-kham, the mantra that represents Mahāvairocana in his Reward Body (J: hōjin; S: sambhogakāya) at the moment of cosmic creation—as depicted in the Womb World Mandala”. (). |

| 24 | Ise e mairaba Asama o kake yo, Asama kakeneba kata sangū; 「お伊勢へ参らば朝熊をかけよ、朝熊かけねば片参宮」(; ). |

| 25 | This type of kanjō is called a jumyō kanjō 受明灌頂, also known as a gakuhō kanjō 学法灌頂. (). According to Itō Satoshi, the ritual procedures for shrine obeisance (shinpai 神拝) and shrine-pilgrimages (shasan 社参) were also called kanjō. He writes that “in the ritual procedure for shrine obeisance, the practitioner took the shrine precincts as the ritual space, the body of the kami (shintai) as the primary icon, formed mudras, chanted mantras, and visualized the kami’s true body (that is an avatar of a buddha, or the same as one’s own mind)”. (). |

| 26 | Uhō Dōji is also identified as a manifestation of Dainichi Nyorai, the primordial Buddha (). |

| 27 | According to Kubota, Version A of the Uhō Dōji keibyaku was written before 1555 (). |

| 28 | For an introduction to the pilgrimage mandala genre in English, see (; ; ; ). |

| 29 | Kokūzō is identified with dawn and celestial light, linked to the “morning star” Venus (Myōjō) around the sixth century in China (; ). |

| 30 | According to Yamasaki, the Gumonji-hō practitioner concentrates exclusively on the single practice union with the deity Venus (Myōjō tenshi) (). According to Nishida, upon successful completion of the Morning Star Meditation (Gumonji-hō), Myōjō tenshi will appear before the practitioner. He goes on to state that Kokūzō is the true form of Myōjō tenshi because he is the lord of the stars; this is why he is also known as Kokūzō daimyōjō tenshi bosatsu (). |

| 31 | In addition, Faure writes: “the wish-fulfilling jewel, in his [the Tendai priest Jihen] view, unites the Yin and Yang, heaven and earth, and the powers of the two Ise shrines”. (). |

| 32 | For example, in the Kasuga Shrine Mandala, Mount Mikasa is placed at the top of the painting with Kasuga’s kami floating above. Moreover, in the Fuji Pigrimage Mandala the composition moves vertically from bottom to top, from the more secular, everyday life towards Fuji’s tripartite peak, each enshrined with a Buddha. Nishiyama Masaru makes a similar argument about the compositional arrangement of the Ise Pilgrimage Mandala in his chapter “Taikon ryōbu sekai no tabibito—Tekusuto 3 Ise sankei mandara,” (). Elizabeth ten Grotenhuis makes the following observation about kami mandalas: “Despite the fact that kami mandara are often decribed as being maplike or realistic in their depiction of geographical details, compositions are sometimes manipulated to emphasize certain details. Sacred Mount Mikasa must appear in the honored position at the top of the composition [in the Kasuga miya mandara], but Mount Mikasa is located in the eastern part of the city of Nara”. () |

| 33 | The other two Ise Pilgrimage Mandalas are housed in the Mitsui Bunko (Tokyo) and the Kimiko and John Powers Collection (Colorado). For analysis of the Ise Pilgrimage Mandala, see (; ; ; ). |

| 34 | Fujiwara no Shunzei (1114–1204), for example, wrote in his diary that he worshiped the Naikū at the Momoe no matsu (; ). |

| 35 | In Shinto meishōshi it says if the Suisaki is correct and the Momoe no matsu was in front of the Naikū then it would have been near the Minami no Shueiya (). |

| 36 | A poem by Tsuchimikado-in no kozaishō (dates unknown) and two poems by Jichin Kasho (thirteenth century) use the phrase “Kamiji yama momoe no matsu” and can be found in (). Kamijiyama in these poems could also refer more generally to the Naikū (). Momoe no matsu was also an expression used in poetic offerings to the Ise shrines when referring to a sacred tree or a spirit dwelling (). |

| 37 | According to the 1707 Ise sangū annaiki (Internal Diary of the Inner Shrine?), the pilgrimage route through the Naikū moved from the Kora no tachi to Isuzugawa Bridge (Kaze no Miya Bridge) to a monk–nun worship hall (). In the late medieval period, Kaze no Miya Bridge and the surrounding area was maintained and occupied by Shingon yamabushi (mountain ascetics) who lived and raised money in a fundraising hall (kokuya) at the base of the bridge. The shrine on the opposite side of the bridge, Kaze no Miya, became a place from where Buddhist monks and nuns worshipped the Naikū. The Kora no tachi and its young residents were thus in close proximity to Buddhist activity. |

| 38 | 御子良子の一もとゆかし梅の花 (Okorago no ichi moto yukashi ume no hana; The shrine maidens (okorago) have a single plum blossom tree). This poem comes from Bashō’s Oi no Kobumi (Records of a Travel Worn Satchel) (). |

| 39 | The kora was originally called monoimi. The new title, which combines the characters for child 子 and good良was changed in the medieval period to emphasize that it was a child who served in this role (). |

| 40 | The cedar tree was called the Ioe sugi 五百枝杉. |

| 41 | There is a large deciduous tree matching Kokan’s description on the side of the Naikū, illustrated adjacent to a hall labeled “Kora no tachi,” in the fourteenth century Ise ryōgū mandara 伊勢両宮曼荼羅 (Nara National Museum), a painting heavily influenced by Shingon Ryōbu Shintō. A large cedar tree in front of the Gekū is labeled Ioe sugi; Kūkai is shown floating above. |

| 42 | Yamamoto Hiroko describes this episode as a dream by a Naikū priest, Arakida Nobutsune, in which he receives an oracle that turns him into a believer of Buddhist law (). |

| 43 | In his Sankeiki, Tsūkai writes that the kora stands at the front of the group of Ise priests during shrine rituals, which Tsūkai interprets as sign of her importance (). |

| 44 | This poem comes right after the poem about the plum tree behind the Kora no tachi in Oi no Kobumi (Records of a Travel Worn Satchel). |

| 45 | A description of four ‘secret’ rituals performed by the kora can be found in Shingon Shintō shūsei, in the section titled “Kora daiji”. These rituals are carried out by the kora as they prepare the food for Ise’s kami. At the end of each of the four rituals the kora recite ‘Ondakinikyachikyakaneineieisowaka’ オンダキニキャチキャカネイネイエイソワカ. According to this source, the kora are a boy and a girl; the boy must leave the position before his 15th birthday; the girl must leave with the arrival of her first period (). |

| 46 | One of these esoteric (mikkyō) rituals, known as the Amaterasu Ōmikami Hihō 天照大神秘宝, was performed by the kora in the food offering hall (御饌殿 mikedono) during the twice daily offerings to the kami. It was believed that if this secret practice was not carried out the emperor would become weak and lose control of the four seas. Another esoteric ritual performed by the kora in Ise’s food offering hall was the sokui kanjō 即位灌頂 (‘enthronement ritual’), which was sometimes called the Dakini-hō 辰狐法, (; ). |

| 47 | On patronage-related issues surrounding the Ise Pilgrimage Mandalas, see (; ). |

| 48 | The three seasonal rites were the biannual tsukinamisai 月次祭, in the sixth and twelth months, and the kannamesai 神嘗祭 in the ninth month. |

| 49 | I am following the translation of shin no mihashira by (). |

| 50 | They write that the saiō would have “suspended the mirror of Amaterasu from an ‘abstinence post’ in a procedure similar to that described in the myth of the Rock-Cave of Heaven”. (). |

| 51 | In fact, according to Odaira Mika, the kora who married the yamabushi of Segidera descended from the saiō (). |

| 52 | For a comprehensive and in-depth discussion of etoki in Japan, see (). |

| 53 | I make a similar argument that the shape of Uji Bridge in the Jingū Chōkokan Ise Pilgrimage Mandala points to the Keikōin nuns’ origins as Kumano bikuni in (). |

References

- Andreeva, Anna. 2010. The Karmic Origins of the Great Miwa Deity: A Transformation of the Sacred Mountain in Premodern Japan. Monumenta Nipponica 65: 245–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, Anna. 2019. ‘To Overcome the Tyranny of Time’: Stars, Buddhas, and the Arts of Perfect Memory at Mt. Asama. In Buddhism and the Dynamics of Transculturality. Edited by Birgit Kellner. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 119–50. [Google Scholar]

- Andrei, Talia. 2018. Ise Sankei Mandara and the Art of Fundraising in Medieval Japan. The Art Bulletin 100: 68–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzai, Nahoko 安西奈保子. 1987. Godaigo tennō wo meguru sannin no saigūtachi 後醍醐天皇をめぐる三人の斎宮たち. Nihon bunka kenkyū 23: 133–46. [Google Scholar]

- Azuma, Yoshisada 東吉貞, ed. 1895. Shinto meishōshi 神都名勝志. 6 vols. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Hanshichi. [Google Scholar]

- Bocking, Brian. 2000. The Oracles of the Three Shrines: Windows on Japanese Religion. Richmond: Curzon. [Google Scholar]

- Chieda, Daishi 千枝大志. 2013. “Ise sangū annaiki” ni miru Ise sangū kōzō no kinseika: Shugenteki sangū kara onshiteki sangū he 『伊勢参宮案内紀』に見る伊勢参宮構想の近世化―修験的参宮から御師的参宮へー. Yūkyū 135: 76–94. [Google Scholar]

- Dolce, Lucia, and Ikuyo Matsumoto. 2010. Girei No Chikara. Gakusaiteki Shiza kara Mita Chūsei Shūkyō no Jissen sekai 『儀礼の力、学際的視座から見た中世宗教の実践世界』. Kyoto: Hōzōkan. [Google Scholar]

- Faure, Bernard. 2016. Gods of Medieval Japan. Volume 1: The Fluid Pantheon. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Faure, Bernard. 2021. Gods of Medieval Japan. Volume 3: Rage and Ravage. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fukudome, Tamami 福留瑞美. 2016. Ise jingū hōnō hyakushu no shosō 伊勢神宮奉納百首の諸相. Kokubugaku 100: 125–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gorai, Shigeru 五来重. 1978. Asamayama shinkō to take mairi 朝熊山信仰とタケ参り. In Kinki reizan to shugendō. Sangaku shūkyōshi kenkyū sōsho 近畿霊山と修験道 山岳宗教史研究総叢書. Edited by Gorai Shigeru. Tokyo: Meicho Shuppan, vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara, Tatsuo 萩原龍夫. 1978. Kamigami to sonraku: Rekishigaku to minzokugaku to no setten 神々と村落―歴史学と民俗学との接点. Tokyo: Kōbundō. [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara, Tatsuo 萩原龍夫. 1983. Miko to bukkyōshi: Kumano bikuni no shimei to tenkai 巫女と仏教史:熊野比丘尼の使命と展開. Tokyo: Yoshikawa kōbunkan. [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara, Tatsuo 萩原龍夫, and Seiji Nishigaki 西垣晴次, eds. 1985. Ise shinkō 伊勢信仰. 2 vols. Tokyo: Yūzankaku. [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi, Ryōkō 浜口良光. 1949. Sengū shōnin: Keikōin ki 遷宮上人—慶光院記. Mie: Jinja Honchō Chōrō. [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa, Caroline. 2013. Hellbent for Heaven in Tateyama Mandara: Painting and Religious Practice at a Japanese Mountain. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Inaya, Yūsen 稲谷祐宣. 1993. Shingon Shintō shūsei 真言神道集成. Osaka: Seizansha. [Google Scholar]

- Ise-shishi Henshū Iinkai 伊勢市史編集委員会, ed. 2011–2013. Ise-shishi 伊勢市史. 3 vols. Ise-shi: Ise Shiyakusho. [Google Scholar]

- Itō, Satoshi 伊縢聡. 1996. Ise kanjō no sekai 伊勢灌頂の世界. Bungaku 8: 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Itō, Satoshi 伊縢聡. 2022. The World of Shintō Kanjō, With a Focus on Ryōbu Shinto. In Rituals of Initiation and Consecration in Premodern Japan. Edited by Fabio Rambelli and Or Porath. Berlin: de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Jingū Shichō 神宮司庁, ed. 1935–1940. Daijingū sōsho 大神宮叢書. Gifu: Seinō insatsu Gifu shiten, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminishi, Ikumi. 2006. Explaining Pictures: Buddhist Propoganda and Etoki Storytelling in Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi, Motomichi 川口素道, ed. 1994. Asamadake Kongōshōji tenseki komonjo 朝熊岳金剛證寺典籍古文書. Mie: Kongōshōji. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, Takeshi 菊池武. 1984. Ise Jingū to bukkyō: Ise wo torimaku kanjin hijiri 伊勢神宮と仏教―伊勢を取り巻く勧進聖―. Indo-gaku Bukkyo-gaku kenkyū 32: 859–61. [Google Scholar]

- Knecht, Peter. 2006. Ise sankei mandara and the Image of the Pure Land. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 33: 232–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Yukio 小林幸夫. 2014. Ise Kongōji no reiseki densetsu: Shirodayū no tamoto ishi 伊勢金剛寺の霊石伝説―白大夫の袂石. Tōkaigakuen Daigaku kenkyū kiyo 19: 203–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, Shōsaku 小島鉦作. 1985. Ise jingūshi no kenkyū 伊勢神宮史の研究. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan. [Google Scholar]

- Kubota, Osamu 久保田修. 1968. Tenshō Daijin to Uhō Dōji: Asamayama shinkō wo chūshin to shite 天照大神と雨法童子―朝熊山信仰を中心として. Kōgakkan ronsō 1: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo, Bashō. 1966. The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Other Travel Sketches. Translated by Nobuyuki Yuasa. Harmondsworth: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, Samuel. 2009. Pilgrimage for Pleasure—Time and Space in Medival Japanese Painting. In Negotiating Secular and Sacred in Medieval Art: Christian, Islamic, Buddhist. Edited by Alicia Walker and Amanda Luyster. Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida, Nagao 西田長男. 1977. Uhō Dōji-zō kanken II 雨法童子像管見(ニ). Shintō oyobi Shintō shi 2: 20–52. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimiya, Hideki 西宮秀紀. 2020. Ōken saishi kara rituryōsei saishi he—Ise jingū, Munakata jinja, Saigū, Dazaifu wo tegakari ni 王権祭祀から律令制祭祀へー伊勢神宮・宗像神社・斎宮・大幸府を手掛かりに. Paper presented at Nishi no miyako, Dazaifu to Oki no shima, Higashi no miyako, saigū to ise jingū—Chiiki saishi no nari tachi to rituryō saishi he no henshitsu 西の都・太宰府と沖ノ島の都・斎宮と伊勢神宮〜地域祭祀の成り立ちと律令祭祀への変質〜, a symposium held at the Kyūshū National Museum, Dazaifu, Japan, January 18; Saigū: Saigū rekishi hakubutsukan. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama, Masaru 西山克. 1989. Sawagashii kamigami 騒がしい神々. In Ise shima rekishi bunkateki kachi no saihakken Ise sankei mandara no shinsō—mandara kara mita chūkinsei no Ise no shosō 伊勢志摩歴史文化的価値の再発見伊勢参詣曼荼羅の真相. Conference Proceedings. Tokyo: Kankyō bunka kenkyū sho, pp. 201–14. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama, Masaru 西山克. 1993. Sankei mandara no jissō 参詣曼荼羅の実相. In Shinpojūmu Ise Jingū シンポジウム伊勢神宮. Edited by Ueyama Shunpei 上山春平. Kyoto: Jinbun Shoin, pp. 158–213. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama, Masaru 西山克. 1998. Seichi no sōzōryoku: Sankei mandara o yomu 聖地の想像力―参詣曼荼羅を読む. Kyoto: Hōzōkan. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama, Masaru 西山克. 1999. Hōju to kinsei: Asamayama engi to Ise 宝珠と金星―浅間山縁起と伊勢. Kokubungaku: Kaishaku to kyōzai no kenkyū, tokushū: Bukkyō ga 44: 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Odaira, Mika 小平美香. 2003. Jingi saishi ni okeru josei shinshoku no hataraki: Kodai jingū, kyūchū no sairei kara 神祇祭祀における女性神職の働きー古代神宮・宮中の祭祀から. Gakushūin Daigaku Jinbun kagaku gakuronshū 12: 41–66. [Google Scholar]

- Odaira, Mika 小平美香. 2010. Chūsei ni okeru jingū "kora" no shosō: Dōji shinkō wo megutte 中世における神宮「子良」の諸相―童子信仰をめぐって. In Chūsei kaiga no matorikkusu I 中生絵画マトリックス I. Edited by Sano Midori 佐野みどり, Shinkawa Tetsuo 新川哲雄 and Fujiwara Shigeo 藤原重雄. Tokyo: Seikansha, pp. 290–311. [Google Scholar]

- Odaira, Mika 小平美香. 2014. Chūsei no Ama no Iwato to Uhō Dōji shinkō—Jingū Chōkokan-bon Ise sankei mandara 中世の天岩戸と雨法童子信仰―神宮徴古館本. In Chūsei Kaiga no Matorikusu II 中生絵画マトリックス II. Edited by Sano Midori 佐野みどり, Kasuya Makoto 加須屋誠 and Fujiwara Shigeo 藤原重雄. Tokyo: Seikansha, pp. 276–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ōnishi, Gen’ichi 大西 源一. 1960. Daijingū shiyō 大神宮史要. Tokyo: Heibonsha. [Google Scholar]

- Ooms, Herman. 2008. Imperial Politics and Symbolics. Hawaii: University of Hawai‘i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rambelli, Fabio. 2014. Floating Signifiers: The Plural Significance of the Grand Shrine of Ise and the Incessant Re-signification of Shinto. Japan Review 27: 221–42. [Google Scholar]

- Rambelli, Fabio, and Or Porath, eds. 2022. Rituals of Initiation and Consecration in Premodern Japan. Berlin: de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, Jonathon. 2001. Ise Shrine and a Modernist Construction of Japanese Tradition. The Art Bulletin 83: 316–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfield, John. 2011. Portraits of Chōgen: The Transformation of Buddhist Art in Early Medieval Japan. Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, Tokutarō 櫻井徳太郎, Hagiwara Tatsuo 萩原龍夫, and Miyata Noburo 宮田登. 1975. Jisha engi 寺社縁起. In Nihon shisō taikei 日本思想大系. Edited by Ienaga Saburō 家長三郎, Fujieda Akira 藤枝晃, Hayashima Kyōshō 早島鏡正 and Tsukishima Hiroshi 築島裕. 67 vols. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, vol. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, Minoru 清水実. 2014. Mitsui Bunko-bon Ise sankei mandara no seisaku nendai ni tsuite—Jingū Chōkokan bon to J. Pawa-zu bon to no hikaku ni yoru 三井文庫本「伊勢参詣曼荼羅」の制作年代についてー神宮徴古館本とJ・パワーズ本との飛白による. Mitsui bijutsu bunkashi ronshū 7: 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Shitomi, Kangetsu 蔀関月. 1797. Ise sangū meisho zue 伊勢参宮名所図会. Osaka: Shioya Chūbē, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Tada, Jitsudō 多田實道. 2019. Ise jingū to bukkyō: Shūgō to kakuri no happyakunenshi 伊勢神宮と仏教: 習合と隔離の八百年史. Tokyo: Kōbundō. [Google Scholar]

- Teeuwen, Mark. 1993. Attaining Union with the Gods: The Secret Books of Watarai Shinto. Monumenta Nipponica 48: 225–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teeuwen, Mark. 1996. Watarai Shinto: An Intellectual History of the Outer Shrine in Ise. Leiden: Research School CNWS, Leiden University. [Google Scholar]

- Teeuwen, Mark. 2000. The Kami in Esoteric Buddhist Thought and Practice. In Shinto in History: Ways of the Kami. Edited by Mark Teeuwen and John Breen. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, pp. 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Teeuwen, Mark, and John Breen. 2017. A Social History of the Ise Shrines: Divine Capital. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Teeuwen, Mark, and Fabio Rambelli. 2003. Buddhas and Kami in Japan: Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. London: Routledge Curzon. [Google Scholar]

- ten Grotenhuis, Elizabeth. 1999. Japanese Mandalas. Honolulu: Univerity of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Toba, Shigehiro 鳥羽重宏. 1997. Amaterasu no zōyō no hensen nitsuite: Jotai-zō nantai-zō kara, Uhō Dōji-zō ni itaru zuzōgaku 天照大神の像容の変遷についてー女体像・男体像から、雨法童子像に至る図像学―. Kōgakkan Daigaku Shintō kenkyūjo kiyō 13: 119–79. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto, Akira 塚本明. 2010. Kinsei Ise jingū ryō ni okeru shinbutsu kankei ni tsuite 近世伊勢神宮領における神仏関係について. Mie Daigaku jinbun gakubu bunka gakuryō kenkyū kiyō 27: 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tsunematsu, Tadashi 恒松侃. 2015. Ise jingū sankei: Matsuo Bashō to Saigyō Hōshi 伊勢神宮参詣 松尾芭蕉と西行法師. Aichi Kokubu 9: 58–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ujiyamada Shiyakusho 宇治山田市役所, ed. 1929. Ujiyamada-shishi 宇治山田市史. 2 vols. Uji Yamada shi: Ujiyamada Shiyakusho. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, Hiroko 山本ひろ子. 2005. Seinaru mono no kōbō: Ise no kora to kora no tachi wo megutte 聖なる者の光芒―伊勢の子良と子良館をめぐって. Tōzainanboku: Wako Daigaku sōgō bunka kenkyūjo nenpō, 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka, Yukiko 山中由紀子. 2020. Higashi no miyako: Saigū to saiō 東の都・斎宮と斎王. Paper presented at Nishi no miyako, Dazaifu to Oki no shima, Higashi no miyako, saigū to ise jingū—Chiiki saishi no nari tachi to rituryō saishi he no henshitsu 西の都・太宰府と沖ノ島の都・斎宮と伊勢神宮〜地域祭祀の成り立ちと律令祭祀への変質〜, a symposium held at the Kyūshū National Museum, Dazaifu, Japan, January 18; Saigū: Saigū rekishi hakubutsukan. [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki, Taikō. 1988. Shingon: Japanese Esoteric Buddhism. Fresno: Shingon Buddhist International Institute. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).