Preoccupation with Devotional Songs and Spiritual Well-Being of Religious Individuals: The Mediating and Moderating Effects of Religiosity and Emotionally Adaptive Functions of Music

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Spiritual Well-Being

2.2.2. Religiosity

2.2.3. Preoccupation with Devotional Songs

2.2.4. Emotionally Adaptive Functions of Music

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Relationship between Variables Involved in the Spiritual Well-Being of Religious Individuals

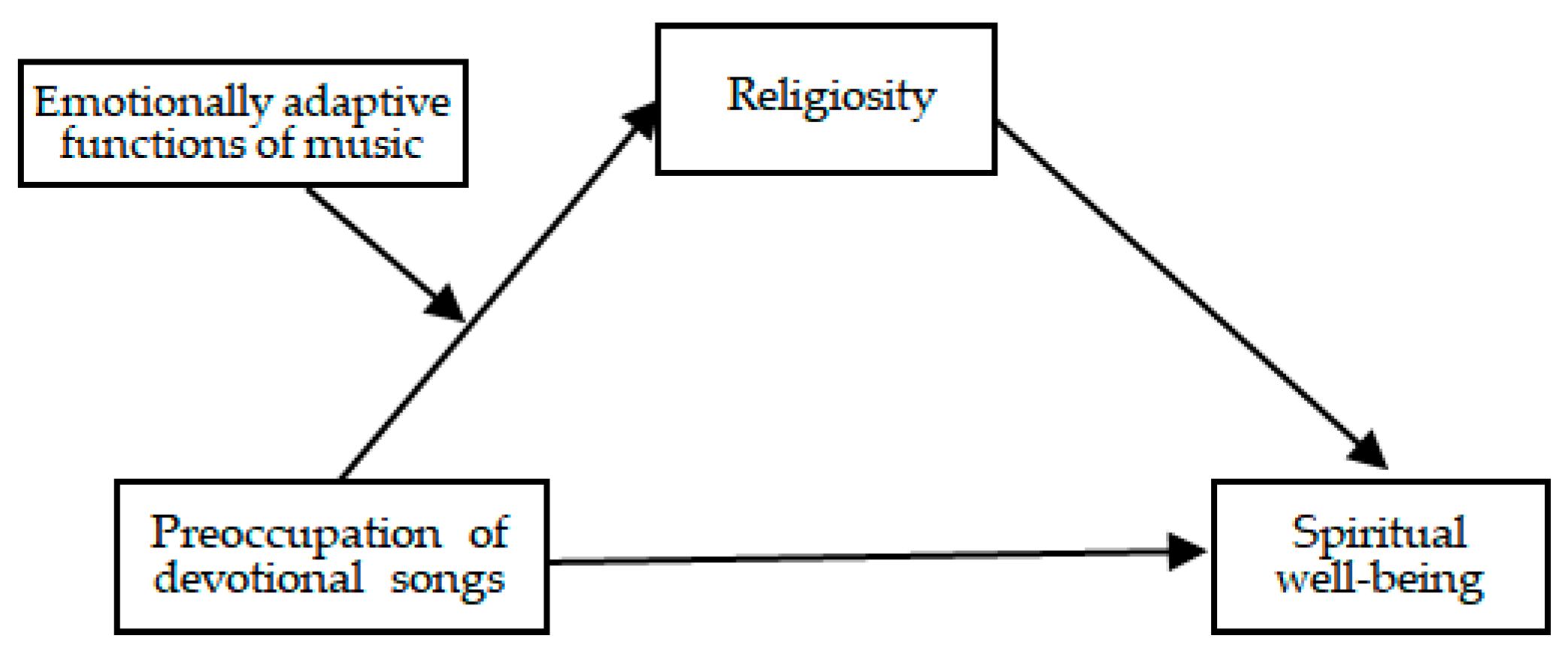

3.2. Verification of the Moderated Mediation Model for Spiritual Well-Being of Religious Individuals

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PDS | preoccupation with devotional songs |

| EAFM | emotionally adaptive functions of music |

| SWBS | Spiritual Well-Being Scale |

| SWLS | Satisfaction with Life Scale |

| I/E-R | Intrinsic/Extrinsic Religious Orientation Scale |

| I | intrinsic religiosity |

| Ep | extrinsic personal religiosity |

| Es | extrinsic social religiosity |

| FML | adaptive Functions of Music Listening scale |

| IRB | institutional review board |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| VIF | variance inflation factor |

References

- Anderson, Fred R. 1990. Three new voices: Singing God’s song. Theology Today 47: 260–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beak, Eunjin, Sung-Jin Chung, and Kyung-Hyun Suh. 2022. Relationship between religiosity and subjective well-being among middle-aged Korean women: Focused on roles of existential consciousness and savoring beliefs. Religions 13: 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Guy L. 2019. Sacred music and Hindu religious experience: From ancient roots to the modern classical tradition. Religions 10: 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bradshaw, Matt, Christoper G. Ellison, Qijuan Fang, and Collin Mueller. 2015. Listening to religious music and mental health in later life. Gerontologist 55: 961–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bruscia, Kenneth E. 2014. Defining Music Therapy, 3rd ed. University Park: Barcelona Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, TanChyuan, and Mikki S. Rickard. 2014. Emotion regulation strategy mediates both positive and negative relationships between music uses and well-being. Psychology of Music 42: 692–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, Rafi M. 2018. Religiosity and voluntary simplicity: The mediating role of spiritual well-being. Journal of Business Ethics 152: 149–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Nicholas. 1998. Music: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, Vladimir Araujo, Rita de Cássia Frederico Silva, Nubia Carla Ferreira Cabau, Eliseth Ribeiro Leão, and Maria Júlia Paes da Silva. 2017. Effects of sacred music on the spiritual well-being of bereaved relatives: A randomized clinical trial. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP 51: e03259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demmrich, Sarah. 2018. Music as a trigger of religious experience: What role does culture play? Psychology of Music 48: 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorsuch, Richard L., and Susan E. McPherson. 1989. Intrinsic/Extrinsic measurement: I/E-revised and single-item scales. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 28: 348–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, Saurabh, and Selina Thielemann. 2005. Music and Fine Arts in the Devotional Traditions of India: Worship Through Beauty. New Delhi: APH Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Groarke, Jenny M., and Michael J. Hogan. 2018. Development and psychometric evaluation of the adaptive functions of music listening scale. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, Susan L. 2014. To sing or not to sing?: Music and the religious experience from 1500–1700. The International Journal of Religion and Spirituality in Society 3: 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2018. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helena, Dukić, and Miro Jakovljević. 2021. Music, religion, and health: A scientific perspective on the origin of our relationship to music. Psychiatria Danubina 33: 143–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hills, Peters, and Michael Argyle. 1998. Musical and religious experiences and their relationship to happiness. Personality and Individual Differences 25: 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Eun-Sik, and Kyung-Hyun Suh. 2012. Religious orientation, fundamentalism, spiritual well-being, and subjective well-being among religious people. Korean Journal of Health Psychology 17: 1067–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukka, Petri. 2007. Uses of music and psychological well-being among the elderly. Journal of Happiness Studies 8: 215–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Angela Yuen Chun, and Jacky Ka Kei Liu. 2021. Effects of intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity on well-being through meaning in life and its gender difference among adolescents in Hong Kong: A mediation study. Current Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipe, Anne W. 2002. Beyond therapy: Music, spirituality, and health in human experience: A review of literature. Journal of Music Therapy 39: 209–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal, Dennis V., Rosabella P. Erillo, and Enrique E. Oracion. 2020. Religiosity and spiritual well-being of senior high school students of a catholic college in the Philippines. Recoletos Multidisciplinary Research Journal 8: 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Mandi M., and Kenneth T. Strongman. 2002. The emotional effects of music on religious experience: A study of the Pentecostal-Charismatic style of music and worship. Psychology of Music 30: 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oracion, Enrique G., and Dennis V. Madrigal. 2019. Catholic identity and spiritual well-being of students in a Philippine Catholic University. Recoletos Multidisciplinary Research Journal 7: 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paloutzian, Raymond E., and Craig W. Ellison. 1982. Loneliness, Spiritual Well-Being and the QUALITY of Life: A Source Book of Current Theory. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Alexander. 2021. ADHD trait, emotional music use, and expectation for future life in early adolescence: Focused on mediating effect of relationship initiation. International Journal of Contents 21: 629–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pio, Frederik, and Øivind Varkøy. 2012. A reflection on musical experience as existential experience: An ontological turn. Philosophy of Music Education Review 20: 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin, Noah, and Jillian Argue. 2014. Theoretical considerations of spirit and spirituality in music therapy. Music Therapy Perspectives 32: 118–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebecchini, Lavinia. 2021. Music, mental health, and immunity. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity Health 18: 100374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibanda, Fortune, and Tompson Makahamadze. 2008. ‘Melodies to God’: The place of music, instruments and dance in the Seventh Day Adventist church in Masvingo province, Zimbabwe. Exchange 37: 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, Kyung-Hyun, and Kyum-Koo Chon. 2004. Spiritual well-being, life stress, and coping. Korean Journal of Health Psychology 9: 333–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tshabalala, Bhekani G., and Cynthia J. Patel. 2010. The role of praise and worship activities in spiritual well-being: Perceptions of a Pentecostal Youth Ministry group. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 15: 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, Melissa K., and Dawn Joseph. 2017. If you’re happy and you know it: Music engagement and subjective wellbeing. Psychology of Music 45: 257–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weiss, Paul. 1963. Religion and Art: The Aquinas Lecture. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press. [Google Scholar]

- West, Stephan G., John F. Finch, and Patrick J. Curran. 1995. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. Edited by Rick H. Hoyle. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Witter, Robert A., Morris A. Okun, William A. Stock, and Marilyn J. Haring. 1984. Education and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 6: 165–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wnuk, Marcin. 2017. In a sample of Polish students’ spiritual experiences mediated between hope and religiosity. In Hope: Ndividual Differences, Role in Recovery, and Impact on Emotional Health. Edited by Francis L. Cohen. New York: Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Frequency | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| male | 210 | 49.2 | |

| female | 217 | 50.8 | |

| Age | |||

| 20s | 81 | 19.0 | |

| 30s | 84 | 19.7 | |

| 40s | 86 | 20.1 | |

| 50s | 86 | 20.1 | |

| 60s | 90 | 21.1 | |

| Religion | |||

| Buddhist | 111 | 26.0 | |

| Catholic | 98 | 23.0 | |

| Protestant | 214 | 50.1 | |

| other | 4 | 0.9 | |

| Attendance at religious services | |||

| none | 132 | 30.9 | |

| once a month | 97 | 22.7 | |

| two or three times a month | 49 | 11.5 | |

| once a week | 117 | 27.4 | |

| more than twice a week | 32 | 7.5 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2 | 0.147 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 3 | 0.757 *** | 0.088 | 1 | |||||

| 4 | 0.410 *** | 0.277 *** | 0.465 *** | 1 | ||||

| 5 | 0.335 *** | 0.112 * | 0.284 *** | 0.246 *** | 1 | |||

| 6 | 0.443 *** | 0.149 ** | 0.522 *** | 0.320 *** | 0.076 | 1 | ||

| 6-1 | 0.530 *** | 0.134 ** | 0.620 *** | 0.384 *** | 0.079 | 0.966 *** | 1 | |

| 6-2 | 0.336 *** | 0.154 ** | 0.400 *** | 0.241 *** | 0.069 | 0.971 *** | 0.876 *** | 1 |

| M | 17.87 | 69.05 | 32.35 | 14.50 | 7.56 | 14.64 | 6.79 | 7.85 |

| SD | 6.19 | 12.72 | 10.04 | 3.51 | 3.63 | 20.93 | 10.39 | 11.22 |

| Skewness | −0.10 | −0.65 | 0.17 | −0.94 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.02 |

| Kurtosis | −0.69 | 1.29 | −0.46 | 1.16 | −0.82 | −0.36 | −0.19 | −0.49 |

| Variables | B | S.E. | t | LLCI | ULCI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediating variable model (Outcome variable: Intrinsic religiosity) | ||||||||

| Constant | 30.042 | 0.655 | 45.89 *** | 28.7553 | 31.3289 | |||

| PDS | 1.203 | 0.053 | 22.71 *** | 1.0984 | 1.3066 | |||

| EAPM | −0.018 | 0.025 | −0.71 | −0.0661 | 0.0310 | |||

| PDS × EAPM | −0.011 | 0.004 | −2.98 ** | −0.0174 | −0.0036 | |||

| Increase of R2 with interaction | R2 | F | ||||||

| 0.009 | 8.87 ** | |||||||

| Dependent variable model (Outcome variable: Spiritual well-being) | ||||||||

| Constant | −14.386 | 4.424 | −3.25 ** | −23.0815 | −5.6896 | |||

| PDS | 0.386 | 0.217 | 1.78 | −0.0403 | 0.8116 | |||

| Intrinsic religiosity | 0.927 | 0.134 | 6.92 *** | 0.6637 | 1.1909 | |||

| Conditional effects of the focal predictor at values of the moderator (EAPM) | ||||||||

| EAPM | Effect | S.E. | t | LLCI | ULCI | |||

| M − 1SD | 1.336 | 0.070 | 19.15 *** | 1.1989 | 1.4731 | |||

| M | 1.203 | 0.053 | 22.71 *** | 1.0984 | 1.3066 | |||

| M + 1SD | 1.069 | 0.069 | 15.49 *** | 0.9334 | 1.2047 | |||

| Conditional indirect effects of intrinsic religiosity by EAPM | ||||||||

| EAPM | Effect | Boot S.E. | LLCI | ULCI | ||||

| −12.72 | 1.251 | 0.203 | 0.8593 | 1.6467 | ||||

| 0.00 | 1.119 | 0.177 | 0.7821 | 1.4727 | ||||

| 12.72 | 0.986 | 0.165 | 0.6789 | 1.3318 | ||||

| Value of the Moderator | B | S.E. | t | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −49.0468 | 1.717 | 0.181 | 9.47 *** | 1.3608 | 2.0740 |

| −45.0968 | 1.676 | 0.168 | 9.97 *** | 1.3455 | 2.0064 |

| −41.1468 | 1.635 | 0.155 | 10.55 *** | 1.3298 | 1.9391 |

| −37.1968 | 1.593 | 0.142 | 11.22 *** | 1.3140 | 1.8721 |

| −33.2468 | 1.552 | 0.129 | 12.01 *** | 1.2977 | 1.8054 |

| −29.2968 | 1.510 | 0.117 | 12.95 *** | 1.2809 | 1.7393 |

| −25.3468 | 1.469 | 0.104 | 14.07 *** | 1.2635 | 1.6738 |

| −21.3968 | 1.427 | 0.093 | 15.41 *** | 1.2450 | 1.6092 |

| −17.4468 | 1.386 | 0.082 | 16.98 *** | 1.2253 | 1.5461 |

| −13.4968 | 1.344 | 0.072 | 18.78 *** | 1.2035 | 1.4849 |

| −9.5468 | 1.303 | 0.063 | 20.66 *** | 1.1788 | 1.4267 |

| −5.5968 | 1.261 | 0.057 | 22.24 *** | 1.1498 | 1.3727 |

| −1.6468 | 1.220 | 0.053 | 22.87 *** | 1.1150 | 1.3246 |

| 2.3032 | 1.178 | 0.054 | 22.04 *** | 1.0732 | 1.2835 |

| 6.2532 | 1.137 | 0.057 | 19.90 *** | 1.0246 | 1.2492 |

| 10.2032 | 1.095 | 0.064 | 17.20 *** | 0.9702 | 1.2206 |

| 14.1532 | 1.054 | 0.072 | 14.57 *** | 0.9117 | 1.1962 |

| 18.1032 | 1.013 | 0.083 | 12.28 *** | 0.8503 | 1.1746 |

| 22.0532 | 0.971 | 0.094 | 10.38 *** | 0.7870 | 1.1550 |

| 26.0032 | 0.930 | 0.105 | 8.82 *** | 0.7224 | 1.1366 |

| 29.9532 | 0.888 | 0.118 | 7.55 *** | 0.6569 | 1.1193 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, A.; Suh, K.-H. Preoccupation with Devotional Songs and Spiritual Well-Being of Religious Individuals: The Mediating and Moderating Effects of Religiosity and Emotionally Adaptive Functions of Music. Religions 2022, 13, 697. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13080697

Park A, Suh K-H. Preoccupation with Devotional Songs and Spiritual Well-Being of Religious Individuals: The Mediating and Moderating Effects of Religiosity and Emotionally Adaptive Functions of Music. Religions. 2022; 13(8):697. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13080697

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Alexander, and Kyung-Hyun Suh. 2022. "Preoccupation with Devotional Songs and Spiritual Well-Being of Religious Individuals: The Mediating and Moderating Effects of Religiosity and Emotionally Adaptive Functions of Music" Religions 13, no. 8: 697. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13080697

APA StylePark, A., & Suh, K.-H. (2022). Preoccupation with Devotional Songs and Spiritual Well-Being of Religious Individuals: The Mediating and Moderating Effects of Religiosity and Emotionally Adaptive Functions of Music. Religions, 13(8), 697. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13080697