1. Introduction

Many Buddhist sculptures are very beautiful, and this beauty is somehow magically enhanced by their supernatural nature, but their bodies, poses, motions, and self-contained repose also contribute significantly to their attractiveness. It matters little that the Buddhist artists in East Asia do not adhere strictly to the anatomical details to any telling degree. They standardize human forms into ideal shapes, which are, at times, determined by iconographic rules. This article studies the Buddhist sitting hierarchy through a case study of an eighth-century Tang-Dynasty Buddhist Bronze collected in the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis (

Figure 1). The posture of this Buddhist sculpture is identified by this author as

lalitāsana: one leg pendant and the other bent horizontally. This article discusses how this pose, as depicted on the sculpture, engenders various other compositional situations and postures that were popular in East Asian icon design, such as the crossed-legs, and royal ease (

rājalīlāsana).

Lalitāsana is comparable to other postures, such as

vama-lalitāsana,

virāsana, or

sukhāsana (see

Figure 2), and much research remains to be conducted to gain a more detailed understanding of these figures, which are vital in Buddhist religion and art.

On the mundane level (Skr.

laukika; Ch.

shijian 世間), Buddhist sculptures serve as expedient means to instruct sentient beings about the Buddhist teachings or

dharma. The internal and external disposition of the figure indicate their status as mere temporary expressions. As a portrayal of the supramundane (Skr.

lokôttara; Ch.

chushijian出世間), the sculpture collapses internal and external expressions in instantiating the real presence of the deity. An ontological statement is issued by means of attributes of an iconographic nature, by body posture, hand gesture, realistic depictions of concrete physical characteristics, and the total definition of these figures through the unified design, which this state of meditation imposes on them down to the minutest detail (

Seckel 1989, p. 83).

However, does the Buddhist bronze under discussion here stand by itself, or did it belong to a group figures (such as a triad)? If so, was it the principal icon, in the middle of a group, or was it a subsidiary icon, situated to the left or right of the main, central figure? In cases in which different figures are joined in groups, the unifying principle is not just some mutual interaction or an arbitrary rule of artistic composition, but a common inner relationship to an outwardly state, forming the very ground of being for them all. Within this assemblage, poses and movements issue from the immobile center, formed by the Buddha figure, to which all of the other figures are formally and doctrinally related. A tentative response to these issues is proposed by investigating postures of this kind within the context of Chinese Buddhist sculpture compositions. It is hoped that, in light of the discussion of the Buddhist bronze in the St. Louis Art Museum, the Buddhist posture hierarchy might be revealed.

2. Identity and Style

Although representations of bodhisattva are often easily recognizable, and conform to a limited sphere in terms of posture, hand gesture, garments, depictions of bodily marks, and other features, depictions of bodhisattva may be so similar that it is sometimes difficult to determine the actual identity of the bodhisattva in a specific image. Throughout the research, it remained unclear whether this figure in St. Louis is an attendant-flanking bodhisattva or a self-standing Guanyin觀音. The lotus pedestal, which connotes divinity, spiritual enlightenment, happiness, and beauty, forms part of the reason for the identification of this bodhisattva as a Guanyin.

However, Guanyin’s connection with Amitābha, his spiritual father, is so intimate that the bodhisattva usually bears a small Amitābha image on his crown. This is frequently the single iconographic clue that enables the identification of Guanyin, who may otherwise look no different to other bodhisattvas (

Weidner and Berger 1994, p. 153). Here, the absence of an iconographic emblem, such as an image of the Buddha Amitābha on the headdress (

guan冠) of the crown, makes it difficult to identify positively this figure as Guanyin.

The sculpture bears no inscription regarding its identification, nor the date when it was cast; however, it can be safely assigned to the early eighth century through stylistic analysis. During the Tang Dynasty, greater interest was ascribed to the volume of the underlying bodies rather than the contours of the drapery (

Chen 2020;

Wu 2017, pp. 102–3). The monumental solidity has been sacrificed through a conscious striving for elegance and rich detail. However, it is uncertain when, during the Tang Dynasty, this figure was cast. If we contrast this St. Louis bronze with an early seventh-century Tang Bronze, such as that depicted in

Figure 3 (the Mayer figure), the evolution is immediately apparent, for the Mayer figure is essentially static, while the St. Louis one is dynamic in character (

Trubner 1957, p. 104).

This Mayer bodhisattva is also seated in the

lalitāsana position, on a high throne, with the right leg pendant, the foot supported on an open lotus, and the left leg folded horizontally. The right hand also holds a lotus flower, while the left, resting on the left knee, holds part of the crossing chains of jewelry which descend from the shoulders and are gathered in large loops over the legs of the figure. However, this Mayer figure is more simplistic, far slenderer, and lacks the full, sensuous modeling, and heavy overlay of jewelry typical of the High Tang style of the late seventh to early eighth centuries (

Fei 1998).

Late in the Tang Dynasty, there was an increasing inclination toward a complication of forms, a break-up of the surface and restless movement of the drapery in a complexity of folds, while the bodies became increasingly stout; a plumpness that was especially evident in the hands and faces. In the St. Louis figure, the drapery caught up in numerous folds over the dais resembles some of the sculptures at Tianlong Shan 天龍山 (

Figure 4), which share the same posture. The Tianlong Shan cave temples (located approximately 40 kilometers southwest of Taiyuan太原, Shanxi山西) were first established during the Eastern Wei東魏dynasty (A.D. 534–550), but were particularly heavily used during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong 唐玄宗between 714 and 740.

1 This Tianlong Shan sculpture was brilliantly conceived and flawlessly executed. By the first quarter of the eighth century, Tang sculpture displayed not only realism but also a marked secularism, as a mirror of the refined opulence and sensuality of the court. The art in Tianlong Shan is more secular than that of any other Tang site of the early eighth century, to the extent that the holiness of the images is undermined.

2The St. Louis sculpture is even more complex and less lucid than the Tianlong Shan sculpture. Considerable beauty, which is, however, languorous to the point of being somewhat heavy, pervades the figure. The orderly pattern of the garment and the hanging scarfs are replaced by an irregular design, in which the flowing scarfs achieve a new, fluid effect. The face of the St. Louis sculpture, with its broad cheeks and small mouth, is a type obviously derived from the ample beauties popular at the Tang court in the days of Emperor Xuanzong (685–762), while being quiescent and supramundane. The bodhisattva’s jewelry, hair and ribbon reflect an amalgamation of West, Central, and South Asian prototypes, with a detailed high-quality technical execution.

3 The earlier, Tianlong Shan bodhisattva wore a large, firmly placed, symmetrical crown; however, that of the St. Louis bronze is smaller and reveals loosely treated hair. The St. Louis piece bears a kind of Indian sensualism: the elegant simplicity and masculinity of the chest derive from Gandhara traditions that were reintroduced in the late seventh and early eighth centuries, when China, which had reestablished its connections with numerous centers in Southern Asia, was crucial in the blooming of diplomatic and economic relations among Persia, India, Central Asia, Korea, and Japan (

Asia Society and Rowland 1963, p. 23). The style of Chinese Buddhist imagery that evolved at the time, through the transformation of assorted new prototypes, also influenced Korea and Japan. It has been named the “International Tang” style (

Metropolitan Museum of Art et al. 2010, p. 104).

While the iconography of this gilt bronze is Indian, and the style shows the influence of Indian art of the Gupta Period (A.D. 320–550), the representation nevertheless remains essentially Chinese. Indian sensualism and semi-nudity have been adapted to suit Chinese taste, so the Tang figure is now clothed in the Buddha’s monastic robe (jiasha袈裟), which is draped loosely over the shoulders and falls in natural folds over the body. The garment, although thin and revealing the shape of the body underneath, has none of the diaphanous, abstract character of the Indian image. In the Tang period, Chinese art was endowed with such vigor and exuberance as to be able to absorb and adapt foreign influences, without becoming overly beholden to them, maintaining, adequately, a conscious indigenous character.

3. Posture

If form mirrors value, then insights into a Buddhist sculpture may be gleaned from an examination of its postures: the Buddhist code for relaxation is languid and graceful poses. Buddhist icons that feature a conventional pose, with deliberate and symbolic postures, convey specific meanings that would have been familiar to devotees.

4The myriad forms of Buddhist postures that have been devised to illustrate the mythologies and philosophical, doctrinal, or even social concepts, and their representations, in turn, have given birth to other myths and beliefs (

Xie 1990, pp. 2–5). Across the ages and in different countries, there has been a ceaseless interaction between the idea that men have derived of deities, and the representations that they have developed from this engagement. An understanding of these deities, their representations, and the evolution of these representations makes it necessary to probe more deeply into the evolution of their forms in the history of Buddhist sculpture. At the same time, the philosophies and representations of these divinities are very different in the various regions: India, South-east Asia, Inner Asia, China, Korea, and Japan. The present research aims to provide an idea of the origin of the Buddhist sculpture postures, identifying the variations in the iconographic forms that they have assumed over the centuries, and furnishing information on the representations of those that have given rise to artistic manifestations in China and parts of East Asia.

Here, the posture of the St. Louis bronze is categorized as

lalitāsana, the posture of relaxation, with one leg bent (usually the left, but sometimes the right) on the throne and the second pendant, or resting on the ground. The pendant leg may be on the side or brought to the center, and rests on a pedestal or a lotus flower.

Lalitāsana is a humanly achievable free-sitting stance that can be observed in previous Buddhist and non-Buddhist artifacts. The position is typical of portrayals of kings, and occasionally queens and court notables, in early Buddhist sculpture, from locations such as as Sanchi, Bharhut, and Amaravati (c. 100 BCE to 200 CE), such as a king and queen in a Jataka scenario depicting an earlier life of the Buddha from Ghantasala, c.200 (

Figure 5). The

lalitāsana pose is seen in religious sculptures in Kushan art (1st to 4th century CE) from Gandhara and Mathura; for example, a 1st century ivory panel unearthed at Begram has

lalitāsana posture (

Figure 6). Miyaji Akira mentioned that both “kings” and “gods” like to sit in

lalitāsana in both Buddhist and Hindu art.

Lalitāsana is a seated posture that expresses comfort and rest, but not only the comfort and luxury of the monarch; it also has symbolic importance in relation to the function of wealth and abundance of the king and the god (

Miyaji 1992, chapter 4). In Indian Buddhist images, Prince Siddhartha is depicted on occasion as the image of Buddha, but predominantly as the image of a king, among whom the posture of

lalitāsana can be seen (

Figure 7). In the Indian Buddhist legend, Prince Siddhartha is depicted as a strong king in the mundane world, with little indication of being troubled or absorbed in meditation, as kings in India are believed to be able to dominate the prosperity of the mundane world (

Miyaji 1992, chapter 4).

Lalitāsana becomes more popular throughout the post-Gupta era of medieval India, especially in Hindu iconography. In Hinduism, the pose is typical for Brahma, Vishu, and Shiva and Uma (

Figure 8). As this article will demonstrate, both the form and connotation of

lalitāsana have seen new developments and changes in China.

Later in the twelfth century, this posture is often adopted for effigies of deities seated on a throne or other seat, and is also customary for deities resting on the backs of support animals. For example, in

Figure 9, Mañjuśrī (Wenshu文殊) is seated on the back of a lion, while in

Figure 10, Samantabhādra (Puxian普賢) sits on the back of an elephant.

The

lalitāsana posture is typical of the images of the Chinese representations of Guanyin, from the Tang and Song eras. A pertinent question is when, and why, the

lalitāsana posture became associated with this bodhisattva Guanyin. By the conclusion of the Gupta dynasty in the sixth century, Avalokiteśvara appeared to have reached the rank of an independent and major deity, who was adored for specific purposes and had his own entourage. As Avalokiteśvara became a great cultic icon, other bodhisattvas accompanied him, much as the Buddha did (

Yu 2001, p. 11). In a number of his manifestations, he assumes the seated position typical of kings—

lalitāsana—signifying his dominion not only over the spiritual realm, but also over the material and mundane realms of glory and reputation. His companions expand in number and significance, enhancing the majesty of the central figure’s position (

Chutiwongs 1984, pp. 49–50). In China, from the Tang Dynasty on, especially the latter part of the Tang period, Guanyin appears in a naturalistic setting associated with Mount Potalaka (the bodhisattva’s sacred abode, based on passages from the

Flower Ornament Sūtra) and is usually seated in the

rājalīlāsana (royal ease) or

lalitāsana posture, which leads to iconographic types such as the Water-Moon Guanyin and the white-robed Guanyin. In Chinese Guanyin belief, the "Water-Moon Guanyin" has a unique cultural and aesthetic meaning and connotation. Examining the evolution of the "Water-Moon Guanyin" image can provide an insight into the inner process of Buddhism’s sinicization. The “Water-Moon Guanyin” is a cultural carrier of the merging of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism (

Zhang 2020). One of the earliest water-moon Guanyin in

lalitāsana or

rājalīlāsana (similar to

lalitāsana) posture is probably the one from Dunhuang Mogao cave 17, produced between 926–975 and now in the British Museum (

Wan and Yang 2021, p. 62) (

Figure 11). Yu Chun-fang stated that this form lacks an undisputed scriptural basis. Only the sutra

Foshuo shuiyue guang Guanyin pusa jing (Sutra Spoken by the Buddha on Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva in the Moonlight on the Water) in Dunhuang provides proof for the existence of a sutra bearing this bodhisattva’s name (

Yu 2001, p. 233). The origins of this iconography are most likely in the eighth and ninth centuries, and there is no question that painters were instrumental in the development of this picture. For example, Zhang Yanyuan (born 815AD) stated in his

Lidai minghua ji (Records of Famous Paintings in History, preface 847) that Zhou Fang (740–800) was the first to paint a water-moon Guanyin in a Chang-an monastery. A full moon encircled the bodhisattva, which was bordered by a bamboo grove. Although the painting has not survived, it may have acted as a model for subsequent painters and sculptors, who popularized this new style of Guanyin in Dunhuang and Sichuan. Both the

Yizhou minghua lu (Notable Paintings of Yizhou, preface 1006) and the

Xuanhe huapu (Catalogue of Paintings Compiled in the Xuanhe Era, preface 1120) show that several famous artists dealt with the image of the water-moon Guanyin. It also served as the inspiration for the white-robed Guanyin (who is more typically portrayed standing), another Chinese manifestation of the bodhisattva that gained popularity during and after the Song (

Yu 2001, p. 235). Although the moon and water, or the moon’s reflection in water, were well-known Buddhist metaphors for the fleeting and impermanent character of things in the universe, there is no scriptural foundation for associating Guanyin with these analogies. This is where we witness Chinese painters’ audacious imagination at work, as they translated Buddhist concepts into the traditional medium of Chinese painting (

Yu 2001, p. 239). The numerous wooden sculptures of Guanyin sitting leisurely, one leg pendant and the other raised, in the posture

rājalīlāsana (royal ease, a variant of the

lalitāsana posture, with the left leg bent horizontally, the right leg bent vertically) or

lalitāsana, which the water-moon Guanyin also frequently assumes, could have been modeled after imported models carried by Buddhist travelers during the Tang and Song periods (

Figure 12). Such figures may be found in Buddhist sculptures produced in Sri Lanka during the ninth and eleventh century. This stance originates in Hindu art, where it is frequently seen in depictions of gods and goddesses (

Gillman 1983). Similarly, Guanyin’s relaxed position, whether lying against a rock or tree, or clasping a knee, is derived from older secular artworks representing seclusion and aristocracy, but not from Buddhist canonical accounts.

The second question is when the lalitāsana posture first became associated specifically with Guanyin in China, and which manifestations of this bodhisattva are most identified with the posture. This, I believe, occurred in the late seventh or early eighth centuries, when Kashmiri art, rather than the Gupta style, was the dominating prototype in China. This is also around the same time that the use of Buddha Amitabha (Amituofo阿彌陀佛) in Guanyin’s headdress became standardized. Both the posture and the use of a family lineage illustrate the development and spread of early esoteric Buddhism. There is a surprising amount of visual evidence for the development of this tradition in China (and Japan); some of it provides “missing pieces,” for the less well-documented Indic traditions.

Northern Buddhism, which essentially belongs to the religious philosophies of the Mahāyāna sects, differs substantially from the forms of Buddhism developed in India, in terms of both its philosophical conceptions and the representations that it assigns to deities and the “forces” venerated by its many sects and schools. When the posture was first used in India, it was not used principally for Guanyin. In Tibetan Buddhism, Green Tāra is often represented in the posture of

lalitāsana; however, the pendant leg is usually brought to the center (

Singh 2021). Tang Dynasty sculptures are more dignified (

duanzhuang端莊) and vertical than in the Tibetan Green Tāra, whereas South Asian ones bear an even more pronounced swaying movement in an S curve (see

Figure 13).

5There are several terms for this type of posture (one leg pendant and the other bent), depending on which leg is bent and which is pendant. Whether or not the bent leg’s toe touches the knee carries different meanings. For example,

Sukhāsana is a ritualized leg position posture and, in general, means being seated in any comfortable position. This term sometimes refers to a seated pose in which the divinity is on a pedestal with the left leg pendant, also known as

savya-

lalitāsana.

Vīrāsana is a sitting pose known as the “Hero’s pose,” in which the left leg rests on top of the right leg, with the toes touching the opposite knee.

Savya-lalitāsana is a seated pose in which the divinity is on a pedestal with the left leg pendant, and the right foot either under or on the left knee. This is also known as

lalitāsana or

sukhāsana (see

Figure 2) (

Capdi and Bunce 1997, p. 339).

Rājalīlāsana (shown in

Figure 14), is a variant of the

lalitāsana posture, the posture of royal ease, with the heels touching or the right foot on the left heel, and is characteristic of many images of Mañjuśrī and Avalokiteśvara, although these postures are sometimes also adopted by other deities (

Frédéric 1995, p. 53). The personages that adopt this attitude are often represented with the elbow (right or left, depending on which leg is raised) nonchalantly resting on the knee, and the other arm supported by the ground (or throne) behind the thigh bent flat, to maintain equilibrium. A variant sometimes shows the personage in

lalitāsana, with the right hand in

Varada mudrā placed on the knee of the pendant leg; this is the

Ardhaparyankāsana posture.

The Buddha himself is, on rare occasions, represented in this attitude, either on images from Gandhara, or in more recent works. The St. Louis bronze shows the gesture of

kataka-mudrā (see

Figure 15), a loose fist-like mudra in which the fingers bend together until the index finger and the thumb meet, forming an open tube. This position is frequently used in icons in which fresh flowers or other venerated objects are inserted (

Capdi and Bunce 1997, p. 142).

In a Jataka tale motif, the Buddha in his former life as King Śibi, is seated in a

lalitāsana posture. According to the tale, which lauds the virtues of benevolence and altruism, Śibi saw a dove fleeing from an eagle one day. When he interceded on behalf of the pigeon, or the Kapotha, the eagle announced that he was starving and that Śibi must replace the meat that the pigeon would have provided with his own flesh. Śibi, who had taken a vow never to harm another living creature, agreed (

Ramesan 1962, pp. 80–84). In a painting on the north wall of cave 254 at Dunhuang of the northern Wei period, the figure standing to the right of the seated king cuts flesh from the ruler’s leg in order to feed a starving eagle (

Figure 16) (

Leidy 2008, p. 75). Here, Sibi is seated at ease in a

lalitāsana posture, seemingly untouched by the pain from the cut in his flesh.

4. Attendant or Principal Figure

A more substantial question remains: is this St. Louis Buddhist Bronze a standalone item, or is it from a group of figures? In China, the Buddhist trinity appeared in the fifth century AD in the three giant figures carved at cave 22 at Yungang. The only dated bronze trinities of this period (which are now in British museums) are, unfortunately, highly questionable, but there can be little doubt that Buddhist trinities were executed in bronze from the very beginnings of Buddhist sculpture in China. Buddhist trinities also occur in Chinese stone sculpture of the fifth and sixth centuries, usually depicting the Buddha Śākyamuni and the Bodhisattvas Avalokiteśvāra and Mahāsthāmaprāpta (Dashizhi-pusa大勢至菩薩). The central figure is usually Amitābha, who, from the Sui period (A.D. 589–618) onward, was conceived as presiding over a triad. However, other Buddhas, such as Maitreya and Bhaiṣajyagūru, sometimes appear as the center of a triad (

Munsterberg 1988, p. 124).

Another question is: if the St. Louis bronze is from a group of figures, does it act as a principal icon in the middle, or is it an attendant-flanking bodhisattva? Traces need to be found in reference to other icons of Chinese Buddhist sculpture. When Buddhist sculpture is held together as a group, the lines of composition—contours, body, garment, and posture—are uniformly applied.

If this is an attendant-flanking bodhisattva next to him, the most popular deity would be either Buddha Śākyamuni or Buddha Amitābha, probably seated. There may be another attendant bodhisattva, with the left leg pendant and the other bent horizontally at the knee, such that they mirror each other in order to form a bracket to emphasize the principal icon in the middle. If this St. Louis Bronze is an attendant-flanking bodhisattva, then, would it be from the right side of the Buddha, or the left, considering its right leg pendant posture? Evidence of this bracketing composition “( )” is manifested in a Northern Wei Dynasty (dated 518) gilt bronze in the Musée Guimet collection (see

Figure 17). The Buddhas Śākyamuni and Prabhūtaratna are seated side by side on a tall pedestal. This Wei period bronze shows images of divine personages with a wide forehead, sharp bridged nose, and small smiling mouth (

Boisselier and Snellgrove 1978, p. 213). Unlike the Tang period, in which the figures were increasingly denuded, the folds of the garment fall in broad, superposed waves, covering the base of the statue and leaving only one or two feet visible (as at Longmen龍門). The attitudes are stiff, hieratic, and full of majesty, while the faces and bodies are lean and slender.

This bronze sculpture attests to the theory that the posture with one leg pendant and the other bent can perform a twin action as a symmetry bracket. The iconography of two Buddhas seated side-by-side is distinctively East Asian and has no parallel in South Asian art. Such paired Buddhas are known to serve as a seminal moment in the

Lotus Sūtra, the first Chinese recension, which was compiled around the third century B.C and became particularly influential in East Asia (

Metropolitan Museum of Art et al. 2010, p. 12).

However rare, exception may be found in a Northern Qi Maitreya stele sponsored by a nun of the Jianzhong Monastery 建忠寺 in 562 AD, and now stored at Longxing Monastery隆興寺, Zhengding正定 County. Two bodhisattva are seated in an opposite bracket “ ) ( ”, and the bodhisattva on the right has his left leg pendant, while the bodhisattva on the left has his right leg pendant, although the same Buddhas as in the Northern Wei bronze are depicted. The front of the stele shows the paired Śākyamuni and Prabhutāratna under a perforated canopy formed by two inter-twined trees (see

Figure 18).

In most examples, this

lalitāsana takes the form of an attendant bodhisattva who is subsidiary to a principal icon in the middle, usually cross-legged or in a seated lotus posture (called

Padmāsana).

6 Hence, bodhisattva in

lalitāsana postures have a close doctrinal relationship with the Buddha. The slight turning of the two bodhisattva figures in a triad, or group, toward the central Buddha figure usually involves a kind of contrapposto, including symmetrical positions of their legs; this attitude can only be understood in terms of their integral relationship to the central figure. Although the individual bodhisattva figures stand asymmetrically and have abandoned a strict frontal position, the paired figures on both sides of the Buddha figure usually cancel out their individual asymmetries by serving as each other’s mirror image. The resulting composition of the triad or group comes to rest in a balanced, unshakable equilibrium, although this is permeated by muted dynamic tensions. Great care is also taken to ensure the unity of movements, the poses of the bodies and extremities, the lie of the garment folds, and the angle of the head, which converge toward the beholder or, to be more precise, the devotees (

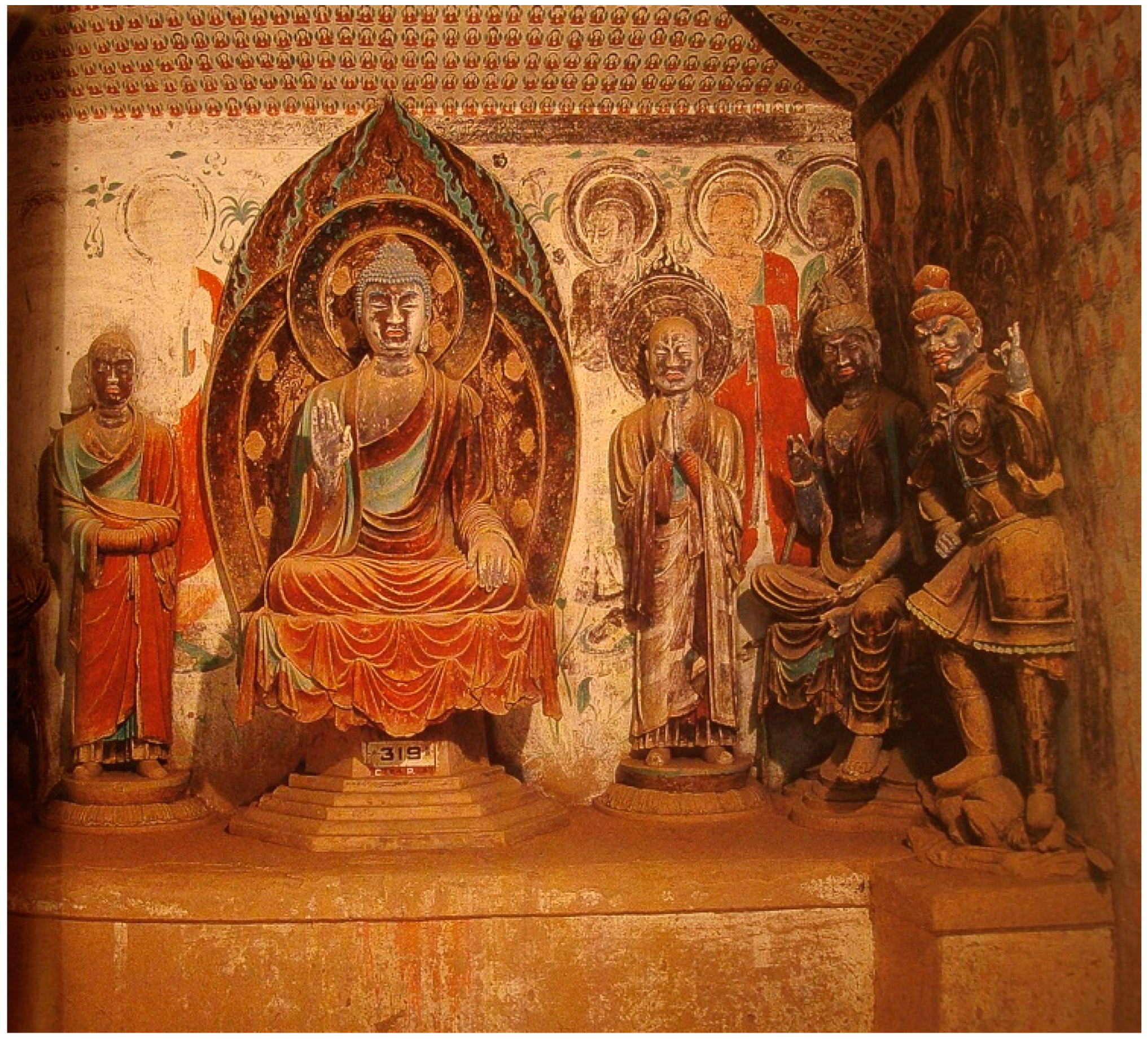

Seckel 1989, p. 99). This is especially obvious in cave 319 at Dunhuang敦煌. Buddha Śākyamuni is seated in the lotus posture, flanked by Mahākāśyapa (Dajiaye大迦葉) and Ānanda (Anan阿難). Next to them are two Bodhisattva in the

lalitāsana posture and standing disciples (

tianwang天王) (see

Figure 19).

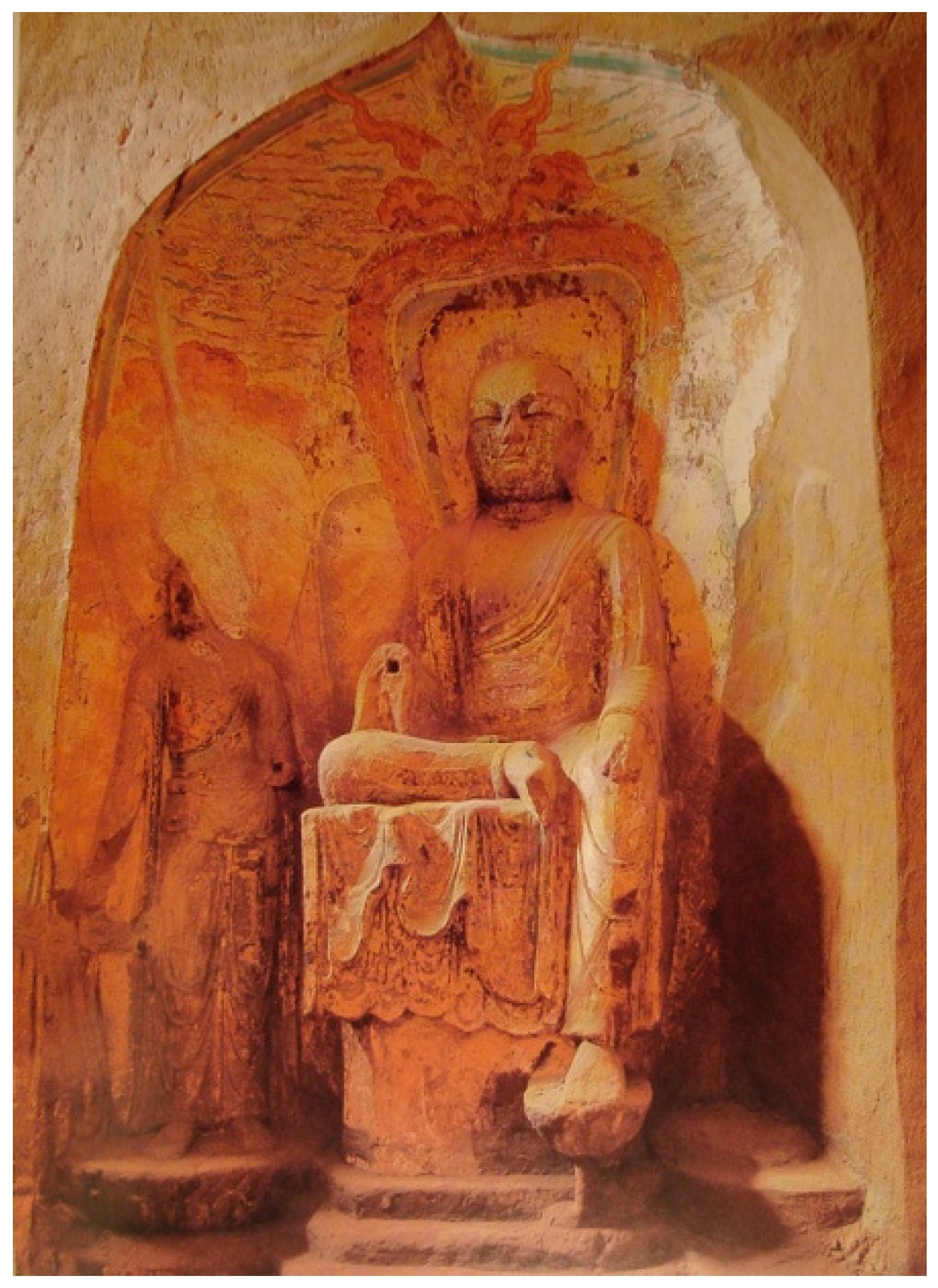

In other cases, the gazes and poses converge toward the central Great Buddha, as in cave 328 in Dunhuang (see

Figure 20). The bodhisattvas subordinate themselves to the central Buddha through their attention. There is a common psychological attention among them, although this expresses itself physically in an independent, individual form in every case.

A more exciting cave at Dunhuang is cave 79 (see

Figure 21). Here, again, Buddha Śākyamuni is seated in the middle, in the lotus posture. Flanking him are his two attendants, Mahākāśyapa to his left and Ānanda to his right. However, instead of a converged gaze toward either the beholder or the central Buddha Śākyamuni, this group’s figures achieve both internal unity and external movement. Instead of mirroring each other symmetrically, the two

lalitāsana posture bodhisattva turn their faces in different directions. The one with the right leg pendant bears an outward gaze to his potential devotees, whereas the one with the left leg pendant seems to be absorbed in his own meditation. Ānanda, instead of facing Buddha Śākyamuni, is gazing at the attendant bodhisattva next to him. As an internal movement, the attendant bodhisattva, regarded by Ānanda, is staring at the central Buddha. As a result, this group of Buddhist figures encompasses a double unity through subordination.

In cave 3 of Beixiang Tang (北響堂), the

lalitāsana posture bodhisattva flank a Buddha in the European seated posture, which is also called the blessed posture (

Bhadrāsana). This is a typical posture of the Buddha Gautama, and of some images of Maitreya, and is found in all Buddhist countries; in India, it is symbolic of royalty (see

Figure 22).

7Although this St. Louis

lalitāsana posture, a subsidiary icon when placed in a triad, is considered mainstream, counter examples can also be found, showing that this posture can also act as a principal icon flanked by other bodhisattva. Regardless of whether it is a subsidiary icon or not, we may assume that this posture has been carried over from the role as an accompanying figure of a Buddha, or, in other words, an attendant bodhisattva, to the rank of a main figure.

8 Such a frontal, slightly S-shaped curve, and the ease created by the one leg pendant and the other bent, document an ontological, rather than a psychological or emotional relationship, between the bodhisattva and ‘his’ Buddha within the hierarchy of levels of existence and being.

In a Tang Dynasty triad niche (cave 105 of Xumishan彌須山, Ningxia Province寧夏), Guanyin, in a

lalitāsana posture, is elevated to the main icon (

zhuzung主尊) of the triad, flanked by two attendant bodhisattva (see

Figure 23). The central Guanyin is seated on a lotus pedestal, with the left foot step on an independent lotus pedal. This finding corroborates the fact that the bronze sculpture of St. Louis (probably also a Guanyin) does not necessarily need to be an attendant bodhisattva, but may, instead, be the main icon. Ksitigarbha (Dizang地藏), on the right side of the same cave, is seated in the same posture, flanked by two standing attendant bodhisattva (see

Figure 24).

In cave 165 of the Beishiku Monastery (Beishiku si北石窟寺) of Northern Wei, Śakra (Dishitian 帝釋天), in the

lalitāsana posture, is flanked by his disciples in a kneeling posture (

Kiza-zō). The kneeling posture used in China, Japan, and India is usually for praying figures and the faithful (see

Figure 25).

9A Tang Dynasty shrine collected at the Kongobu-Ji Monastery (金剛峯寺), Wakayama (see

Figure 26), shows how the pose is able to serve a Buddhist hierarchy, and how the status of this

lalitāsana posture can be determined according to the posture set along with it. The principal icon in the middle of this triad is Buddha Śākyamuni in the pose of

Vajraparyanka, with the left foot on the right thigh. This posture is mainly used for seated effigies of the Great Buddhas (

Frédéric 1995, p. 55). The

lalitāsana postures adopted by his two attendant bodhisattvas are now subsidiary to the Great Buddha’s

Vajraparyanka posture. At the same time, the attendant bodhisattvas in the

lalitāsana posture are flanked by other minor figures in

Kiza-zō, the kneeling posture, and

Samāpada or

Tribhanga, the standing postures. Standing postures, sometimes stiff and symmetrical, but sometimes swaying, can be assumed by virtually all of the deities.

Two identical bronze figures were found by this author in the Seattle Art Museum and MOA, Shiznoka (see

Figure 27 and

Figure 28).

10 They are also seated in

lalitāsana and are garbed and bejeweled in a similar fashion to the St. Louis deity. The only noticeable differences are the closed eyes, the greater tilt of the head, and, to an extent, the more sinicized appearance of the Seattle figure compared to the MOA ones. This finding might reveal the popularity of this model of sculpture, and this bodhisattva may well stand alone, or be the main cult image (

benzun本尊). Moreover, unlike some life-size stone sculptures in the

lalitāsana posture, these figures have been removed from their original context and collected in a museum, so their original grouping is not represented. The fact that a gilt bronze icon in

lalitāsana posture is standing as a solitary figure is, in itself, not unusual (see

Figure 29 and

Figure 30).

An identical gilt bronze is found in the Alsdorf collection, but this is from the Qing Dynasty, probably from the late seventeenth century (see

Figure 31). This also shows the bodhisattva in the

lalitāsana position, with one hand resting on the leg and the other presenting the end of a scarf. The forms of this Qing bronze are soft and ornate, recalling the style of the late Tang period. This represents an archaistic revival and the reproduction of the High Tang style, with a less opulent body.

5. Conclusions

The posture of lalitāsana embodies the meditative repose and equanimity. This is a posture of a figure at ease that is often assumed by bodhisattva, and reflects their accessibility in the phenomenal world, especially in comparison with the supreme perfection and remoteness of the Buddha. In the Tang Dynasty, this posture marked the culmination of the Tang ideal of the union of the natural and the spiritual.

Buddhist sculptures define, through their postures, their own essence, and the essence of their relationship to the Buddha. The peculiar efficacy suggested through the posture and its composition extends beyond the body language itself. It may be concluded that there is a hierarchy within the poses of Buddhist sculpture. When the lalitāsana pose encounters a lotus-seated posture (such as Vajraparyanka, Kichijo-za-zō, and Sattvaparyanka), cross-legged, or European posture (Bhadrasāna), it is usually a subsidiary icon. It seems that those postures are more powerful than the lalitāsana pose. When the lalitāsana is the main icon, it is usually flanked by standing bodhisattva or figures in kneeling postures (referred to as Kiza-zō). Kneeling postures are reserved for praying figures and minor personages, and represent an attitude typical of veneration. The posture in which a deity is represented depends on by whom he is accompanied. When presented as the acolyte of another, the deity is usually portrayed in a less dominant pose.

There is no definite answer to the question about whether this St. Louis bronze is attendant or not, or whether it stood alone or was placed among a group of figures. A mere mirrored figure, such as with the left leg pendant and right bent to this icon, is found; however, the majority of lalitāsana icons appear with the right leg pendant. The present author believes that this icon is either a principal icon, or, more likely, stands alone, which is not unprecedented. If the bronze sculpture is intended as a central icon, then Guanyin on Mount Potakala would be the intended theme. It is less possible that the St. Louis sculpture was an attendant of a larger assemblage. Given the scale, it is much more likely to have been intended for personal devotion, probably as an early form of the water-moon Guanyin.

Buddhist figures of different religious ranks in the pantheon are clearly characterized by their poses and degree of movement. Such symbolic forms, or formulae, are never left to the artist’s imagination. Rather, it was the artist’s task to impart to these perfectly remote entities as tangible a presence as possible, and to point through them to that state which, as the ultimate ground of being, transcends all images. The rubric of presence within absence presented a heartening religious prospect and is one of the most admirable aspects of Buddhist art, especially for so “earthy” an art as sculpture, in which the best works have, nevertheless, drawn from this paradox in an astounding fashion. An important element in this realization of a religious archetype, based on a religious idea transcending all ideas, images and representations, is these sublime and yet compassionate poses of the Buddhist statues. They are simultaneously strictly formal and yet at ease, possess profound silence and also tremendous, albeit hidden, efficacy. These images, even more than the sacred texts, allow us to experience, in a most compelling way, the true Buddha.