The Path of ‘No’ Resistance to Temptation: Lessons Learned from Active Buddhist Consumers in Thailand

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Background

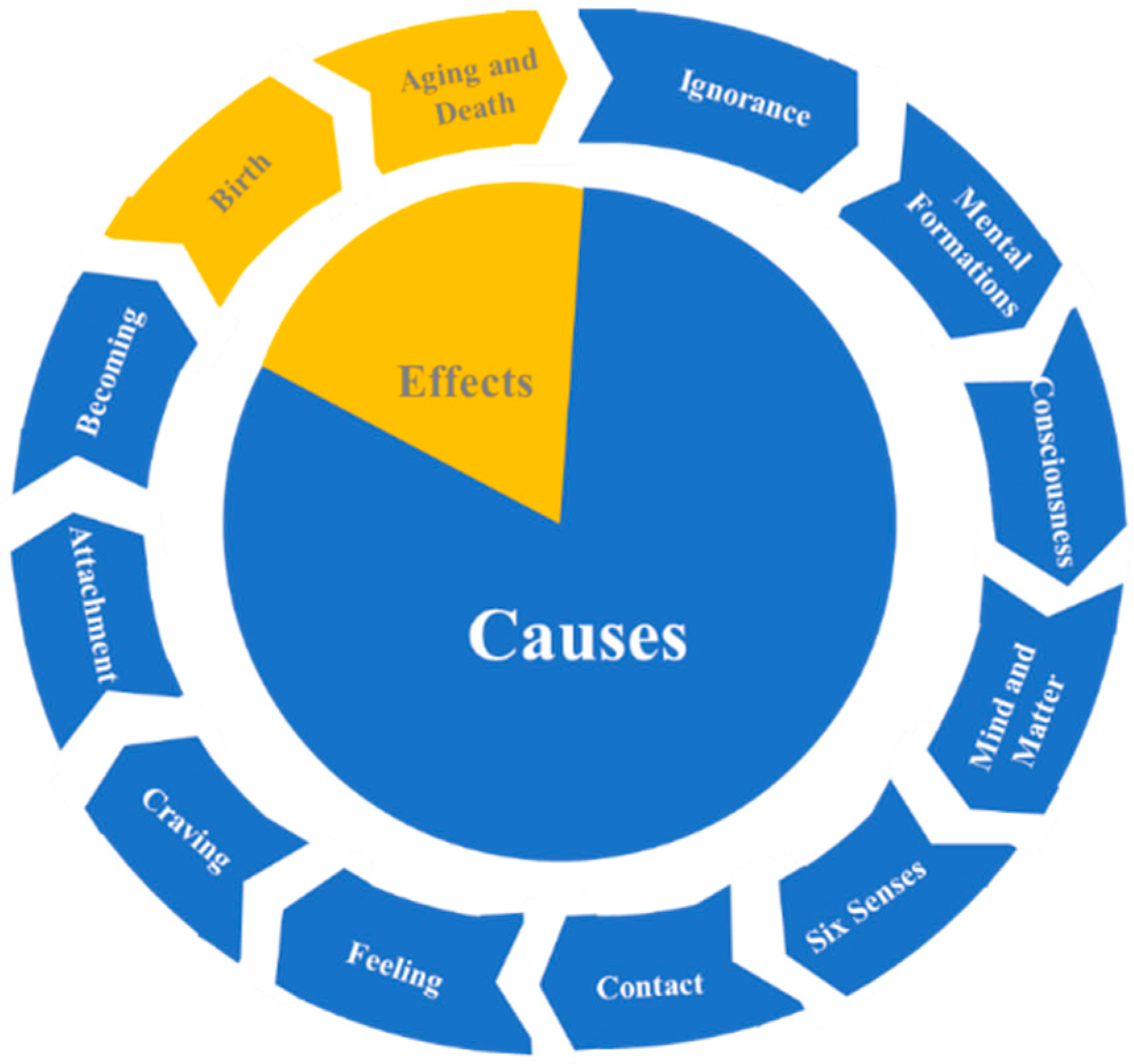

2.1. Consumerism and the Vicious Cycle

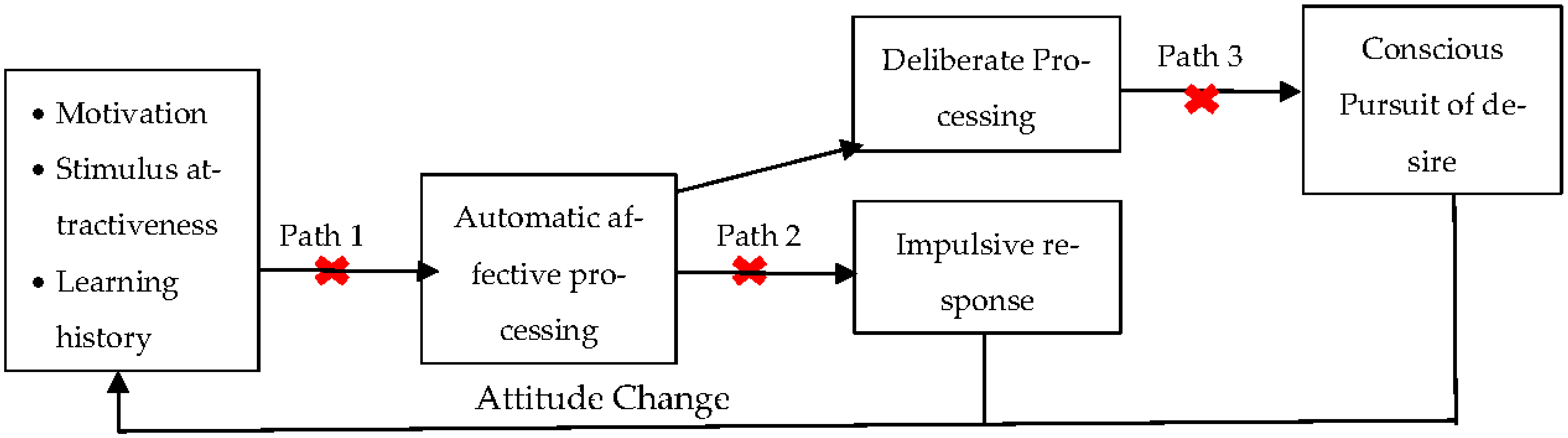

2.2. Self-Control Strategies Defending against Consumerism

2.3. Mindfulness and Buddhist Consumption

3. Methodology

4. Findings

4.1. Consumption Behavior Patterns

Opas: “After being ordained, I realize that we consume four necessities beyond what is needed. In the past, I bought clothes that have never been used. I spent millions decorating a house while I spent more time at the office. I enjoyed eating to satisfy my desires rather than hunger, resulting in being overweight.”Ball: “In the past, when I felt stressed, I drank to escape from problems. I sought a delicious dish to enjoy and compensate for my daily tiredness. I wore a gold necklace to show my success and a batch ring to show my relationship with my classmate. I bought an iPhone and Starbucks as symbols of the modern lifestyle. Now I realize that these do not help improve my life or achieve my long-term goal, so I eliminate them. I want to have enough food to survive and live in a small house but safe enough to protect me. I no longer traded stock daily to become rich. I change to a value investor and trade for financial security.”

Ball: “When my iPhone was out of order, I went to the store asking for any brand I could call and surf the Internet, and I chose the reasonably priced one. I ignore extra features and brands. I realize that brand-name is not real and meaningless. I visited the massage house less than before and resorted to Qigong which gives me good health, not temporary comfort. Before, I traveled with my friends every month to have fun. After practice for years, the desire for such activities disappears. Today, I don’t feel like traveling, going to karaoke/parties, or participating in other activities that cannot help me liberate myself. I donated comic books I collected. I found playing Facebook and online communities is a futile waste of my time, better spend on meditating.”

Yui: “I have stopped eating meats after practice. I felt bad that we let tastiness take away animals’ lives. My lifestyle changed; I frequently visited temples instead of nightclubs. I observe monks’ simple life, so my fashion style changes to be minimal; no make-up and hair dye. I became less attached to the brand name. I can use any brand that is reasonably priced and of moderate quality. Further, I’d like to support products sold for charity purposes, although I may not need such products.”

Ball: “When I eat or use products, I no longer cling to them. Before, if I enjoyed a dish/movie, I kept thinking of it, revisited the restaurant/theater, and wrote an online review to share with others. Now, I no longer enjoy searching for restaurants. For food I like, I still feel that it tastes good, but I enjoy it to a lesser degree and only at the time I am eating. After that, I don’t think about them. Only focus on the current moment.”

4.2. Stages of Behavioral Change

Ball: “I started practicing after reading the book “It is a pity the dead didn’t read this book”, which made me question the purpose of life. The book challenged me to follow at least one of the 5 precepts for 3 months and see the result myself. After I tried to stop drinking, I found myself smarter and sleep well than before”.

Tara: “When I practiced meditation, I learned to focus my attention on my breath. It was not easy and not fun to pay attention to only the breath. My mind often wandered, and it had me think about many things (good, bad, neutral) from the past or future, even something I never thought I would think about, like nuclear. It was scary that my mind never stopped thinking; many are evil thoughts. I had to tell it to stop and to focus on the breath again”.

Kanya: “When I practice Vipassana, I observe motions on different body parts like a heartbeat and sweat. It was fascinating to see that different body parts elicit different feelings (e.g., painful, itchy, burning, electric feel), and even some areas like the elbow can feel some motions though very light. The teacher told us that for each thought, feeling, or body sensation that arises, just observe, not meddle with it. We could see it fades away, arise again, and fades again. I wondered how my numb feeling would disappear if I didn’t change my posture. To my surprise, when I tried to bear the pain patiently, the feeling’s actually gone.”

Anna: “When I went on a retreat in India for two weeks, on the first day, I felt like I was in prison. I felt regretful and scared. I had to sleep with others and take a bath in cool water, an experience that was not comfortable. Meditating the whole day was exhausted and painful. Sometimes, I was not allowed to change my posture. I felt itchy, painful, numb, and upset. I was confused about what I could learn, but I could not go back. I wanted to know what happened at the end. After two days, I got used to the new environment. I learned I’m fine even though I eat two meals, sleep on a hard mattress, and cannot use the Internet. It was a great discovery that my life does not need many things, but I can live happily.”

Ball: “I decided to really follow the precepts when I found out that giving up drinking is good for my health. In the first year, I did fewer mean things, like kill fewer mosquitoes and eat less meat. I stop doing all of these things in the second year. I feel I am kinder and happier. Practicing changed the way my mind worked, making it more moral and clean.”

Ball: “It is not easy to practice; I have to control my mind and action when I see my favorite food. It was awkward telling my friends that I would no longer be drinking with them. At first, they tried to get me to drink, but I said no. Then, sometimes, they put social pressure on me, which hurts. Finally, I stopped hanging out with those friends and joined a group of friends who enjoyed being outside in nature.”

Primproa: “I was recently shopping at a mall and walked past a beautiful dress that matched my taste. Even though something in my head said it was unnecessary, I tried to come up with a counterargument that it could be used in the future, and I finally bought the dress with an initial sense of satisfaction. Later on, a sense of guilt emerged. 2000 THB I spent on the dress would be enough to buy a necessity like food for several days. I became angry at myself. Why did I buy it? Where has my minimalist style gone? This dress is unnecessary, and I can easily rent designer clothes these days. In the end, since I can’t return the dress I purchased, I must forgive myself and move on, promising not to succumb to the temptation next time.”

Opas: “I love eating and always eat two dishes a meal before. As I have practiced being mindful of physical activity and mental formations, I was aware of the taste of the food for the first bite, the second bite, and so on of which the flavor goes dull, aware of where I sense the taste, aware that I was swallowing rice, and aware of changes in my body such as stomach expanded and the feeling of fullness, and thus no need for the second dish.”

Ball: “While trying to follow the 8 precepts every day, I was overly strict with myself, particularly regarding what I eat. I won’t eat Chinese food that uses XO (brandy) sauce. I became a vegetarian and thought that meat eaters were bad people. I even told a meat-eating friend that they had body odor. I was not at ease with those around me who did not adhere to Buddhist precepts. I also force myself to move slowly, eat and chew slowly, and refrain from listening to music that does not help my practice progress. I felt terrible about myself when I couldn’t control myself and gave in to a food craving.”

Kloy: “Buddha did not teach us not to consume but rather to consume with valid reasons and in suitable circumstances. As a woman, it is difficult to be ordained, I still have to live in this world, and consumption is still necessary. I still go shopping when I need certain products to live my life or work. I can go into the store if there is a sale, but whether I buy or not depends on my needs. If there is a chance, I can still eat well, but I no longer yearn for it or feel guilty about taking or not taking it.”

Ball: “I now understand the middle path. When I am hungry, I eat but do not eat for meaning. I can eat without counting pieces and calories and stop when full. If friends invite me to join a trip, I feel neutral between going and not going. I may join the trip if I think I can learn new good experiences and the budget permits. I did not cause trouble for anyone. I still like some food, but I no longer feel aroused by it. Earlier, if I had a desire for a certain food, I had to control such desire. Now I feel free. I do not need to control it. I can see the desire comes and goes. I do not feel positive when fulfilling it or negative when I do not.”

4.3. Process of Change

Jae: “In the past, when I argued with my boss, I went shopping and bought expensive things like an expensive diamond, Bose, Karen Millen, I regret later. After regular concentration meditation, I controlled anger better before. Since my mood is stable, I no longer shopped as retail therapy.”

Mook: “I stop listening to music as it can arouse my emotions. Listening to songs makes me tired, hindering me from achieving my meditation goal. Often, when we listen to happy or sad songs, we become daydreaming or depressed even when we have no experiences as in the song. Today, I listen to Dhamma talk instead.”

Gate: “It is like when we are young, we play with sands and rocks, when we grow up, we learn that these are bad and we stop playing with them. If we are not mindful, we are blind to the risks or harms consumerism can cause. For example, behind good taste, if we over-consume, we will have health problems. After regular practice, I have learned to leverage reasoning to overcome desires.”

Nitcha: “If you are mindful, you will realize that buying things does not make you happy. When I was younger, I wanted a brand-name bag like my friends’. I was anxious as I looked for the right one and kept up with new collections. When I used my first LV bag, I worried it would get dirty, damaged, or lost. I always put the pad there to keep my bag from getting dirty. I had to put it in a plastic bag when it rained to avoid stains. I have hurt again when the bag I hardly ever used went out of style.”

Kloy: “I remember when I was studying in the United States and had to bring a lot of stuff back home.” I felt burdened and exhausted. Many items still carry a price tag. Some of them were worn but never used. Products, like humans, can grow old and die. Today, when I buy new items, I use them rather than keep them, and I only buy when necessary.”

Koi: “Recently, my mom told me someone wants to sell a husky puppy. I imagine how cute it is for seconds, then I think about how I have to spend time playing with it, taking care of its food and poo, and feel sad when it dies. I decide not to adopt it.”

Opas: “Once we own a product, later we get bored, we want a new one, we get bored again, and want a new one again and again. So why do we struggle to get a product in the first place?”Gate: “I consume fewer goods and services because happiness from consumption fades away quickly, and I need to consume again to be happy. Now I found authentic happiness. Dhamma practice brings real, not shallow happiness obtained from consumption. It is light, not extreme, not exciting but could fulfill my mind and lasts longer.”

Anna: “I’m now easily satisfied. I can feel happy when meditating, viewing the beauty of the sky, enjoying the breeze, and seeing the leaves dance.”Ball: “When I meditate, I feel deeply peaceful and relaxed, so now I don’t have to go outside shopping or hang out with friends to be happy. I just stay at home, sit back and relax with meditation, and I’m happy. Today, I’m happier when meditating than traveling and watching movies, so I have stopped thinking of those activities. Meditation fulfills my mind. It’s like when we’re full, we can’t eat anymore. I can’t think of other things when my mind is full.”

Mook: “Practicing Dhamma helped reduce my ego. I care less about what others people think of me. Just doing good things is enough. My mind has been uplifted. I become kind-hearted and ashamed of sin. My internal value is enhanced when I feel I’m a good person. I do not need to use a high-end brand to show my value. Those products are meaningless; they cannot enhance my value.”

Koi: “We learned in a seminar, and I tried to remind myself about this: when we don’t mark a product as ‘My belongings,’ we don’t suffer when a product changes its condition (old, worn, stop functioning). We become neutral when a product rather than our product gets lost.”

Kloy: “When we use luxury goods, we can see that we feel proud, we become cheerful, but what’s the point of showing off when others would not feel like you? Showing yourself is meaningless.”Aim: “In the past, I was complimented when using perfume. I felt more confident and loved, so I became addicted to perfume. I want others to think of good smell when they think of me. Now self-identity is not important. I realize that confidence is created from within, not dependent on materials. Therefore, the role of perfume disappeared.”

Koi: “I attended a one-month ‘how to be a human’ course. We learned the process of how suffering begins and ends and practiced deconstructing five aggregates in our daily lives. In a class, I saw (conscious) someone’s polka dot ‘Kate Spade’ bag (physical form). I recalled that it is a polka dot, and I always like anything polka dot (memory) because it is cute (perception). Seeing it made me happy (feeling), and I thought it would be nice to own it (mental formation). Without the memory “I always like polka dot,” I don’t think I like that polka dot bag. That is Aha! Moment, I felt enlightened. When I saw a polka dot on any object later, I felt I did not have to like every polka dot, and I didn’t like them as much as before.”

5. General Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Armstrong, Cosette M. Joyner. 2021. Fashion and the Buddha: What Buddhist economics and mindfulness have to offer sustainable consumption. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 39: 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, Shalini, George R. Milne, Spencer M. Ross, and Kwong Chan. 2013. Mindfulness: A long-term solution for mindless eating by college students. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 32: 173–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bahl, Shalini, George R. Milne, Spencer M. Ross, David Glen Mick, Sonya A. Grier, Sunaina K. Chugani, Steven S. Chan, Stephen J. Gould, Yoon-Na Cho, Joshua D. Dorsey, and et al. 2016. Mindfulness: Its transformative potential for consumer, societal, and environmental well-being. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 35: 198–210. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, Steve, Anthony Patterson, and Kim Harris. 2006. Beyond technology acceptance: Understanding consumer practice. International Journal of Service Industry Management 17: 111–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudrillard, Jean. 1998. The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures. Newbury Park: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, Roy F. 1997. Esteem Threat, Self-Regulatory Breakdown, and Emotional Distress as Factors in Self-Defeating Behavior. Review of General Psychology 1: 145–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, Roy F. 2002. Yielding to Temptation: Self-Control Failure, Impulsive Purchasing, and Consumer Behavior. Journal of Consumer Research 28: 670–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, Russell W. 1988. Possessions and the Extended Self. Journal of Consumer Research 15: 139–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, Russell W. 2011. Philosophies for less consuming societies. In Changing Consumer Roles. Edited by Karin Ekstrom and Kay Glans. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, Russell, Eileen Fischer, and Robert V. Kozinets. 2013. Qualitative Consumer & Marketing Research. London: Sage Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Berlyne, D. E. 1970. Novelty, Complexity, and Hedonic Value. Perception & Psychophysics 8: 279–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H. Russell. 2002. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods, 3rd ed. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bodhi, Bhikkhu. 2021. The Great Discourse on Causation: The Mahānidāna Sutta and Its Commentaries. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, Tina, Laura S. Stanszus, Sonja M. Geiger, Daniel Fischer, and Ulf Schrader. 2018. Mindfulness training at School: A way to engage adolescents with sustainable consumption? Sustainability 10: 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazier, Caroline. 2003. Buddhism on the Couch: From Analysis to Awakening Using Buddhist Psychology. Berkeley: Ulysses Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, Judson A., Sarah Mallik, Therasa A. Babuscio, Charla Nich, Hayley E. Johnson, Cameron M. Deleone, Candace A. Minnix-Cotton, Shannon A. Byrne, Hedy Kober, Andrea J. Weinstein, and et al. 2011. Mindfulness training for smoking cessation: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 119: 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickman, P. D., and D. T. Campbell. 1971. Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In Adaptation Level Theory. Edited by Mortimer Herbert Appley. New York: Academic, pp. 287–305. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Kirk Warren. 2015. Mindfulness Training to Enhance Positive Functioning. In Handbook of Mindfulness: Theory, Research, and Practice. Edited by Kirk Warren Brown, J. David Creswell and Richard M. Ryan. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Kirk Warren, and Richard M. Ryan. 2003. The Benefits of Being Present: Mindfulness and Its Role in Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84: 822–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Kirk Warren, Tim Kasser, Richard M. Ryan, P. Alex Linley, and Kevin Orzech. 2009. When what one has is enough: Mindfulness, financial desire discrepancy, and subjective well-being. Journal of Research in Personality 43: 727–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, Kath. 2005. Snowball sampling: Using social networks to research non-heterosexual women. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8: 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brox, Trine, and Elizabeth Williams-Oerberg. 2017. Buddhism, business, and economics. In The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism. Edited by Michael Jerryson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 504–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cayton, Karuna. 2012. The Misleading Mind: How We Create Our Own Problems and How Buddhist Psychology Can Help Us Solve Them. Novato: New World Library. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, Richard, Eleonora Gullone, and Nicholas B. Allen. 2009. Mindful Emotion Regulation: An Integrative Review. Clinical Psychology Review 29: 560–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidakis, Andreas, and Michiael S. Lee. 2013. Anti-consumption as the study of reasons against. Journal of Macromarketing 33: 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrier, Hélène. 2009. Anti-consumption discourses and consumer-resistant identities. Journal of Business Research 62: 181–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, Michiael S., Lisa E. Woodrich, and Kristin A. Tiernan. 2014. Using cognitive interviews to assess the cultural validity of state and trait measures of mindfulness among Zen Buddhists. Mindfulness 5: 145–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W. 1998. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cushman, P. 1990. Why the self is empty: Toward a historically situated psychology. American Psychologist 45: 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstrand, Ulf, and Anders Biel. 1997. Pro-Environmental Habits: Propensity Levels in Behavioral Change1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 27: 588–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, Peter. 2011. Buddhism and sustainable consumption. In Ethical Principles and Economic Transformation—A Buddhist Approach. Edited by Laszlo Zsolnai. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 35–60. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva, Padmal. 1990. Buddhist Psychology: A Review of Theory and Practice. Current Psychology 9: 236–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLeire, Thomas, and Ariel Kalil. 2010. Does Consumption Buy Happiness? Evidence from the United States. International Review of Economics 57: 163–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, Ravi, and Klaus Wertenbroch. 2000. Consumer Choice between Hedonic and Utilitarian Goods. Journal of Marketing Research 37: 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed. 2009. Subjective Well-being. In The Science of Well-being. Edited by Ed Diener. Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London and New York: Springer, pp. 11–58. [Google Scholar]

- Eberth, Juliane, Peter Sedlmeier, and Thomas Schäfer. 2019. PROMISE: A model of insight and equanimity as the key effects of mindfulness meditation. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckhardt, Giana. 2011. Buddhism and Consumption. In AP-Asia-Pacific Advances in Consumer Research Volume 9. Edited by Zhihong Yi, Jian Jian Xiao, June Cotte and Linda Price. Duluth: Association for Consumer Research, pp. 358–59. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Xuan Joanna, Christian U. Krägeloh, D. Rex Billington, and Richard J. Siegert. 2018. To what extent is mindfulness as presented in commonly used mindfulness questionnaires different from how it is conceptualized by senior ordained Buddhists? Mindfulness 9: 441–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengler, Wolfgang, and Homi Kharas. 2021. A Long-Term View of COVID-19’s Impact on the Rise of the Global Consumer Class. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2021/05/20/a-long-term-view-of-covid-19s-impact-on-the-rise-of-the-global-consumer-class/#:~:text=The%20global%20consumer%20class%20is,before%20COVID%2D19%20hit%20everyone (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Fischer, Daniel, Laura Stanszus, Sonja Geiger, Paul Grossman, and Ulf Schrader. 2017. Mindfulness and sustainable consumption: A systematic literature review of research approaches and findings. Journal of Cleaner Production 162: 544–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florsheim, Paul, Sarah Heavin, Stephen Tiffany, Peter Colvin, and Regina Hiraoka. 2008. An Experimental Test of a Craving Management Technique for Adolescents in Substance-Abuse Treatment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 37: 1205–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, Pascal, Anna Sundermann, and Daniel Fischer. 2019. How mindfulness training cultivates introspection and competence development for sustainable consumption. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 20: 1002–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, Erich. 1976. To Have or to Be? London: Cox & Wyman. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, Neva, Julie A. Nelson, Frank Ackerman, and Thomas Weisskopf. 2008. Microeconomics in Context. Armonk: ME Sharpe. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, Paul. 2010. Mindfulness for psychologists: Paying kind attention to the perceptible. Mindfulness 1: 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunaratana, Henepola. 2012. The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Sharad, Weng Marc Lim, Harsh Verma, and Michael Polonsky. 2021. Precursors and Impact of Mindful Consumption. In NA-Advances in Consumer Research. Edited by Tonya Williams Bradford, Anat Keinan and Matt Thomson. Seattle: Association for Consumer Research, vol. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Hafenbrack, Andrew C., Zoe Kinias, and Sigal G. Barsade. 2014. Debiasing the mind through meditation: Mindfulness and the sunk-cost bias. Psychological Science 25: 369–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, Murtaza, Randall Shannon, and George P. Moschis. 2022. Sustainable consumption research and the role of marketing: A review of the literature (1976–2021). Sustainability 14: 3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E. T. 1997. Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist 52: 1280–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, Wilhelm, and Lotte Van Dillen. 2012. Desire the New Hot Spot in Self-Control Research. Current Directions in Psychological Science 21: 317–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, Wilhelm, Roland Deutsch, Katie Lancaster, and Mahzarin R. Banaji. 2010. Cooling the Heat of Temptation: Mental Self-Control and the Automatic Evaluation of Tempting Stimuli. European Journal of Social Psychology 40: 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, Morris B., and Elizabeth C. Hirschman. 1982. The Experiential Aspects of Consumption: Consumer Fantasies, Feelings and Fun. Journal of Consumer Research 9: 132–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzel, Britta K., Sara W. Lazar, Tim Gard, Zev Schuman-Olivier, David R. Vago, and Ulrich Ott. 2011. How Does Mindfulness Meditation Work? Proposing Mechanisms of Action From a Conceptual and Neural Perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science 6: 537–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Phan Y., David A. Lishner, and Kim H. Han. 2014. Mindfulness and eating: An experiment examining the effect of mindful raisin eating on the enjoyment of sampled food. Mindfulness 5: 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, Wayne D., and Deborah. J. MacInnis. 2008. Consumer Behavior. Mason: South-Western. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, L., C. M. Bulik, and V. Anstiss. 1999. Suppressing Thoughts about Chocolate. International Journal of Eating Disorders 26: 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking Fast and Slow. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh, David J., Jackie Andrade, and Jon May. 2005. Imaginary Relish and Exquisite Torture: The Elaborated Intrusion Theory of Desire. Psychological Review 112: 446–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Uzma, and Ravi Dhar. 2006. Licensing Effect in Consumer Choice. Journal of Marketing Research 43: 259–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieschnick, John. 2003. The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kivetz, Ran, and Itamar Simonson. 2002. Earning the Right to Indulge: Effort as a Determinant of Customer Preferences toward Frequency Program Rewards. Journal of Marketing Research 39: 155–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopalle, Praveen K., Donald R. Lehmann, and John U. Farley. 2010. Consumer expectations and culture: The effect of belief in karma in India. Journal of Consumer Research 37: 251–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotabe, Hiroki P., and Wilhelm Hofmann. 2015. On Integrating the Components of Self-Control. Perspectives on Psychological Science 10: 618–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KPMG International. 2020. Consumers and the New Reality: Preparing for Changing Customer Needs, Behaviors and Expectations. Available online: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2020/06/consumers-and-the-new-reality.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Kraisornsuthasinee, Suthisak, and Fedrick William Swierczek. 2018. Beyond consumption: The promising contribution of voluntary simplicity. Social Responsibility Journal 14: 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama, Dalai. 2005. The Meaning of Life: Buddhist Perspectives on Cause and Effect. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Langdon, Shani, Fergal William Jones, Jane Hutton, and Sue Holttum. 2011. A grounded-theory study of mindfulness practice following mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Mindfulness 2: 270–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascu, Dana Nicoleta. 1991. Consumer Guilt: Examining the Potential of a New Marketing Construct. In NA-Advances in Consumer Research. Edited by Rebecca H. Holman and Michael R. Solomon. Provo: Association for Consumer Research, vol. 18, pp. 290–93. [Google Scholar]

- Leavey, Gerard, Kate Loewenthal, and Michael King. 2007. Challenges to sanctuary: The clergy as a resource for mental health care in the community. Social Science & Medicine 65: 548–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lennerfors, Thomas Taro. 2015. A Buddhist future for capitalism? Revising Buddhist economics for the era of light capitalism. Futures 68: 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, Sidney J. 1959. Symbols for Sale. Harvard Business Review 37: 117–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, Antoine, Heleen A. Slagter, John D. Dunne, and Richard J. Davidson. 2008. Attention Regulation and Monitoring in Meditation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 12: 163–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, Sonja. 2011. Hedonic Adaptation to Positive and Negative Experiences. In Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping. Edited by Susan Folkman. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 200–24. [Google Scholar]

- Malpas, Simon. 2005. The Postmodern. London: Psychology Press. New York: The United States of America. [Google Scholar]

- Malter, Alan J. 1996. An Introduction to Embodied Cognition: Implications for Consumer Research. In NA-Advances in Consumer Research. Edited by Kim P. Corfman and John G. Lynch Jr. Provo: Association for Consumer Research, vol. 23, pp. 272–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mathras, Daniele, Adam B. Cohen, Naomi Mandel, and David Glen Mick. 2016. The effects of religion on consumer behavior: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Consumer Psychology 26: 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, Michael E., and Brian L. Willoughby. 2009. Religion, Self-Regulation, and Self-Control: Associations, Explanations, and Implications. Psychological Bulletin 135: 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlhenny, James H. 1990. The New Consumerism: How Will Business Respond. At Home with Consumers 11: 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mick, David Glen. 2017. Buddhist psychology: Selected insights, benefits, and research agenda for consumer psychology. Journal of Consumer Psychology 27: 117–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, Steven. 1998. Consumerism: As a Way of Life. Newbury Park: Sage Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Milne, George R., Francisco Villarroel Ordenes, and Begum Kaplan. 2020. Mindful consumption: Three consumer segment views. Australasian Marketing Journal 28: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraven, M., R. F. Baumeister, and D. M. Tice. 1999. Longitudinal Improvement of Self-Regulation through Practice: Building Self-Control Strength through Repeated Exercise. The Journal of Social Psychology 139: 446–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutakalin, Gullinee. 2014. Buddhist economics: A model for managing consumer society. Journal of Management Development 33: 824–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numkanisorn, Subhavadee. 2002. Business and Buddhist Ethics. The Chulalongkorn Journal of Buddhist Studies 1: 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Nyantiloka. 1946. The Word of the Buddha, 11th ed. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society. [Google Scholar]

- O’curry, Suzanne, and Michal Strahilevitz. 2001. Probability and Mode of Acquisition Effects on Choices between Hedonic and Utilitarian Options. Marketing Letters 12: 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, Patrick, and Nick Pisalyaput. 2015. The sufficiency economy: A Thai response to financial excesses. In The Philosophy, Politics, and Economics of Finance in the 21st Century: From Hubris to Disgrace. Edited by Patrick O’Sullivan, Nigel Allington and Mark Esposito. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 300–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pace, Stefano. 2013. Does Religion Affect the Materialism of Consumers? An Empirical Investigation of Buddhist Ethics and the Resistance of the Self. Journal of Business Ethics 112: 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packard, Vance. 1957. The Hidden Persuaders. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 2002. Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work 1: 261–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payutto, P. A. 1994. Buddhist Economic: A Middle Way for the Market Place, 2nd ed. Translated by Dhammavijaya, and Bruce Evans. Bangkok: Buddha Dhamma Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Payutto, P. A. 1995. Dependent Origination: The Buddhist Law of Conditionality. Translated by B. Evans. Bangkok: Buddhadhamma Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2020. Religious Composition by Country (2010–2050). Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2015/04/02/religious-projections-2010–2050/ (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Pollock, Carrie L., Shane D. Smith, Eric S. Knowles, and Heather J. Bruce. 1998. Mindfulness Limits Compliance with the That’s Not-All Technique. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 24: 1153–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongsakornrungsilp, Siwarit, and Theeranuch Pusaksrikit. 2011. Consuming Buddhism: The Pursuit of Happiness. In NA-Advances in Consumer Research. Edited by Rohini Ahluwalia, Tanya L. Chartrand and Rebecca K. Ratner. Duluth: Association for Consumer Research, vol. 39, pp. 374–78. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Stephanie D., and Brian D. Vickers. 2014. The psychology of acquisitiveness. In The Interdisciplinary Science of Consumption. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 127–46. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, James O., and Carlo C. DiClemente. 1984. The Transtheoretical Approach: Crossing Traditional Boundaries of Change. Homewood: Dorsey Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, James O., Carlo C. DiClemente, and J. C. Norcross. 1992. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist 47: 1102–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prothero, Andrea, Susan Dobscha, Jim Freund, William E. Kilbourne, Michael G. Luchs, Lucie K. Ozanne, and John Thøgersen. 2011. Sustainable consumption: Opportunities for consumer research and public policy. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 30: 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Puntasen, Apichai. 2004. Buddhist Economics: Evolution, Theories and Its Application to Various Economic Subjects. Bangkok: Amarin. [Google Scholar]

- Pusaksrikit, Theeranuch, Siwarit Pongsakornrungsilp, and Pimlapas Pongsakornrungsilp. 2013. The Development of the Mindful Consumption Process through the Sufficiency Economy. Duluth: ACR North American Advances. [Google Scholar]

- Rand, Y. 1993. Modes of Existence (MoE): To Be, to Have, to Do—Cognitive and Motivational Aspects, Paper Presented at the International Association for Cognitive Education. Israel: Nof Ginosar. [Google Scholar]

- Rosch, Eleanor. 2007. What Buddhist meditation has to tell psychology about the mind. AntiMatters 1: 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, Erika L. 2004. Mindfulness and Consumerism. In Psychology and Consumer Culture: The Struggle for a Good Life in a Materialistic World. Edited by T. Kasser and A. D. Kanner. Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 107–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rounding, Kevin, Albert Lee, Jill A. Jacobson, and Li-Jun Ji. 2012. Religion Replenishes Self-Control. Psychological Science 23: 635–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachamuneewongse, Siriporn. 2018. Euromonitor: Locals to Spend 30.7% More by 2022. Available online: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/news/1574802/euromonitor-locals-to-spend-30-7-more-by-2022 (accessed on 28 February 2019).

- Sayādaw, Mahāsi. 2017. A Discourse on Dependent Origination. Rangoon: Association for Insight Meditation. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, Ernst Friedrich. 1973. Small Is Beautiful: Economics as If People Mattered. London: Blond & Briggs. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, Shauna L. 2009. The integration of mindfulness and psychology. Journal of Clinical Psychology 65: 555–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehryar, Omar, Timothy D. Landry, and Todd J. Arnold. 2001. Defending against Consumerism: An Emergent Typology of Purchase Restraint Strategies. Duluth: ACR North American Advances. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, Jagdish N., Nirmal K. Sethia, and Shanthi Srinivas. 2011. Mindful consumption: A customer-centric approach to sustainability. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 39: 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, Jagdish N., Bruce I. Newman, and Barbara L. Gross. 1991. Why We Buy What We Buy: A Theory of Consumption Values. Journal of Business Research 22: 159–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaraksa, Sulak. 2009. Rediscovering Spiritual Value: Alternative to Consumerism from a Siamese Buddhist Perspective. Bangkok: Sathirakoses-Nagapradipa Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Stanszus, Laura Sophie, Pascal Frank, and Sonja Maria Geiger. 2019. Healthy eating and sustainable nutrition through mindfulness? Mixed method results of a controlled intervention study. Appetite 141: 104325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research Techniques. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Swagler, Roger. 1997. Consumer Rights. In Encyclopedia of the Consumer Movement. Edited by Stephen Brobeck. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, pp. 168–69. [Google Scholar]

- Thanissaro, Bhikkhu. 1997. Parivatta Sutta: The (Fourfold) Round. Access to Insight (BCBS Edition). Available online: http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn22/sn22.056.than.html (accessed on 28 February 2019).

- Thanissaro, Bhikkhu. 2008. The Shape of Suffering: A Study of Dependent Co-Arising. Valley Center: Metta Forest. [Google Scholar]

- Thiermann, Ute B., and William R. Sheate. 2021. The way forward in mindfulness and sustainability: A critical review and research agenda. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement 5: 118–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tice, Dianne M., and Ellen Bratslavsky. 2000. Giving in to Feel Good: The Place of Emotion Regulation in the Context of General Self-Control. Psychological Inquiry 11: 149–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Veer, Evelien, Erica Van Herpen, and Hans C. Van Trijp. 2016. Body and mind: Mindfulness helps consumers to compensate for prior food intake by enhancing the responsiveness to physiological cues. Journal of Consumer Research 42: 783–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Essen, Elisabeth, and Fredrika Mårtensson. 2014. Young adults’ use of food as a self-therapeutic intervention. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 9: 23000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, Jonathan, and David Loy. 2002. The Religion of Consumption: A Buddhist Perspective. In Mindfulness in the Marketplace: Compassion Responses to Consumerism. Edited by Allan Hunt Badiner. Berkeley: Parallax Press, pp. 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wertenbroch, Klaus. 1998. Consumption Self-Control by Rationing Purchase Quantities of Virtue and Vice. Marketing Science 17: 317–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintrobe, Ronald. 2019. Adam Smith and the Buddha. Rationality and Society 31: 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wornkorporn, Pimchanok. 2020. Thai People Spend 18 Billion Baht to Make Merit on Holy Things. Bangkokbiznews. Available online: https://www.bangkokbiznews.com/business/906563 (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Yani-de-Soriano, Mirella, and Stephanie Slater. 2009. Revisiting Drucker’s theory: Has Consumerism Led to the Overuse of Marketing? Journal of Management History 15: 452–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsolnai, Laszlo. 2011. Why Buddhist Economics? In Ethical Principles and Economic Transformation—A Buddhist Approach. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

| Object | Description of Mindfulness Practice |

|---|---|

| 1. Body | Nonjudgmental awareness, attention, or focus of

|

| 2. Feelings |

|

| 3. States of Mind |

|

| 4. Dhamma |

|

| Name | Gender | Age | Ethnics | Occupation | Years of Practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ball | Male | 35 | Asian | Employee | 7 |

| Kanya | Female | 33 | Asian | Employee | 2 |

| Mook | Female | 37 | Asian | Government Officer | 2 |

| Jae | Female | 48 | Asian | Self employed | 6 |

| Aim | Male | 36 | Asian | Government Officer | 12 |

| Anna | Female | 24 | Western | PhD Student | 5 |

| Yui | Female | 37 | Asian | Self employed | 4 |

| Gate | Male | 50 | Western | Employee | 7 |

| Koi | Female | 38 | Asian | Housewife | 1 |

| Tara | Female | 40 | Asian | Housewife | 3 |

| Opas | Male | 45 | Asian | Employee | 10 |

| Kloy | Female | 36 | Asian | Self employed | 17 |

| Nitcha | Famale | 55 | Asian | Self employed | 2 |

| Nan | Female | 34 | Asian | Government Officer | 7 |

| Primprao | Famale | 33 | Asian | Employee | 4 |

| Mode of Existence | Mechanism | Strategy | Behavioral Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wongkitrungrueng, A.; Juntongjin, P. The Path of ‘No’ Resistance to Temptation: Lessons Learned from Active Buddhist Consumers in Thailand. Religions 2022, 13, 742. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13080742

Wongkitrungrueng A, Juntongjin P. The Path of ‘No’ Resistance to Temptation: Lessons Learned from Active Buddhist Consumers in Thailand. Religions. 2022; 13(8):742. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13080742

Chicago/Turabian StyleWongkitrungrueng, Apiradee, and Panitharn Juntongjin. 2022. "The Path of ‘No’ Resistance to Temptation: Lessons Learned from Active Buddhist Consumers in Thailand" Religions 13, no. 8: 742. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13080742

APA StyleWongkitrungrueng, A., & Juntongjin, P. (2022). The Path of ‘No’ Resistance to Temptation: Lessons Learned from Active Buddhist Consumers in Thailand. Religions, 13(8), 742. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13080742