Abstract

The Malay World has been home to a range of social formations, from nomadic hunter-gatherers on land and sea, through (semi-)sedentary swiddeners and forest traders, to state-incorporated peasants and aristocrats. In their religious and secular musics, these populations display differing performance manners and organisation that reflect their distinctive socio-cultural and religious orientations. The musics serve to embed those orientations as aesthetically felt rather than conceptually talked about. The differences are encoded mainly onto contrasts between, on the one hand, highly heterophonic and/or starkly non-melismatic performance and, on the other, more homophonic and/or melismatic styles.

1. Introduction

The Malay World has been home to a range of social formations, from nomadic hunter-gatherers on land and sea, through (semi-)sedentary swiddeners and forest traders, to state-incorporated peasants and aristocrats. In their endogenous1 religious and secular musics, these populations display differing performance manners and organisation that reflect their distinctive socio-cultural and religious orientations. The musics serve to embed those orientations as aesthetically felt rather than conceptually talked about. The differences are encoded mainly onto contrasts between, on the one hand, highly heterophonic and/or starkly non-melismatic performance and, on the other, more homophonic and/or melismatic styles. These contrasts are exhibited in both religious and secular contexts.

As I show later, there is carry-over between core religious and non-religious contexts, the latter being necessarily also peripherally religious. By the ‘core’ of religious action, I refer to ‘the direct, unmediated, non-articulated communication with a non-empirical Thou, called into existence in and by that very communicative act’ (Benjamin 2014a, p. 16). Certain forms of communicative activity, which almost always include musical performances, are inherently religious regardless of how they are labelled by the performers themselves, because they share the same shaping of the worldview as the more ‘core’ religious activities. ‘Religious’ and ‘secular’ are used here as analytical terms, not as translations of local terminology, with the aim of recognising the distinctive features of various forms of activity. Performers and listeners do not usually draw any such distinction explicitly, since (1) such understandings work at a tacitly condensed and implicit level, and (2) those tacit understandings are held at a level of consciousness that bridges both the religious and the secular.2

Alongside my primary ethnographic research over the years, I have been examining certain features of Malay-World musics (Benjamin 2019a, 2019b) as performed in tribal and non-tribal, egalitarian and hierarchical, and land-dwelling and maritime populations. The tribal populations (Benjamin and Chou 2002) have included nomadic hunter-gatherers and sedentary cultivators; the more settled populations have included both rural and urban people. Although these studies were not explicitly directed at religious music, important connections can nevertheless be drawn between the secular and religious domains, if the latter are broadly conceived as including not only overtly religious rituals but also the underlying modes of societal consciousness sustained by both domains.

In what follows, I outline the relation in the Malay World between musical performance and various underlying socio-cultural factors, including the spill-overs between religious and secular musics discussed in detail elsewhere (Benjamin 2019b, pp. 93–111). As used here, ‘Malay World’ refers rather narrowly to the areas currently or formerly falling under kerajaan Melayu (the rule of a Melayu king) (Milner [1982] 2016).3 It therefore incorporates the territories of the various Melayu kingdoms and their attendant hinterlands that have existed or still exist along the coasts of Borneo, the east coast of Sumatra and adjoining islands, and on the Malay Peninsula into southern Thailand. It does not refer to other parts of Indonesia, nor to the Austronesian-speaking world as a whole—both of which are sometimes misleadingly referred to as the Malay World, despite the very different cultural patterns they exhibit. On the other hand, the Malay World as used here does include the various Austronesian- and Austroasiatic-speaking non-Melayu populations who live within its bounds.4

Societally, the Malay World was—and still is in some places—divided into elites, peasants and tribespeople. This tripartite division was the result of pre-modern state-formation, where previously there had been no such division. Elites—a shorthand term for priests, tax collectors, the military and so on, as well as kings and aristocrats—are those who placed themselves in command. Peasants are those whose lives were controlled by agencies of the state, which they provisioned in exchange for a little reflected glory but no counter-control. Tribespeople are those who have resisted the state’s incorporative peasantisation by holding themselves culturally aloof from it.5

Before recent modernisation and rural proletarianisation took effect in the Malay World, peasants formed the majority population: they followed the dominant religion (Islam) and spoke the dominant language (Malay). The tribespeople however were, and frequently still are, much more variegated. They include both Austronesian-speakers—the non-Melayu Malays—and (in the Peninsula) Austroasiatic-speakers, traditionally living mostly off swiddening and forest-trading, and practising their own localised animistic religions.

The interstices between the peasants and most of the tribespeople were occupied by various smaller and less sedentary hunter-gatherer populations, living variously off the forests, strands or seas. They also ‘foraged’ opportunistically off neighbouring populations, through seasonal farm-labour, portering, trading forest or maritime products (including game meat and seafood), and—importantly for present purposes—providing musical and dance entertainment for more settled people, especially the Orang Melayu.

The social differences between tribespeople, peasants and elites, and between sedentary and less-sedentary, are reflected in the different ways in which their musics are organised and the manner in which they are performed. As Marc Perlman (1998, p. 45) remarks more generally,

Musical elements and practices are remarkably versatile carriers of social meaning. By making distinctions of pitch, duration, dynamics, timbre, form, or performance practice, cultures can express differences of gender, ethnicity, class, generation, social status, or religion. These social distinctions are often encoded in easily perceptible musical features such as instrumentation, vocal quality, or ornamentation. However, social distinctions are not projected only by such relatively accessible musical features; they can also be conveyed through subtle differences in musical technique.

Perlman’s comment ties in nicely with the ‘aesthesis’ of my title, which refers to the embedded unspoken felt values engendered and supported by musical performance. All of the populations discussed in this account are explicitly aware of the various features I have outlined as typical of their musical performances, but they are less forthcoming about why those particular features work in the way they do. Of course, most of the audio and video examples referred to in this paper were produced by people who were simultaneously both the makers and experiencers of their music. This means that their music involves both active and entrained bodily movement (as in foot-tapping, swaying, dancing, drumming), as well as the auditory merging of their own sounds with those of their fellow performers. As Blacking (1974, p. 111) famously pointed out, ‘to feel with the body is probably as close as anyone can ever get to resonating with another person.’

In what follows, musical performance in the Malay World is examined with regard to the following features:

- Performance organisation: this refers to such features as heterophony versus homophony (unison), or canon versus separated chant-and-response, or hocketing versus complete individual parts.6 These variants are well known to ethnomusicologists working in different parts of the world.

- Performance manner refers to at least two sets of contrasting features: singing in a plain versus embellished manner, and singing to an accompaniment of solidary choral percussion versus a more differentiated fuller instrumentation.

With regard to the region’s hunter-gatherers, there are two key factors that relate to this pair of contrasts: first, that they are hunter-gatherers in particular; and second, that they are also tribespeople in the more general sense. In the Malay World, a third relevant factor is that even the Austroasiatic- (Aslian-)speaking populations—both sedentary and nomadic—have developed their musical traditions within a broadly Austronesian environment. This relates especially to their preference for accompanying song performances by choral percussion playing, a practice that extends all the way into the Pacific (Hornbostel 1926, p. 277; Kolinski 1930, p. 587, 608 ff.).

2. Performance Organisation

I look first at the contrasts between the patterns followed by the sedentary Temiars and the formerly nomadic Bateks—Austroasiatic-speaking Orang Asli populations of northern Peninsular Malaysia. The differences are obvious in recordings I made of song performances among the two populations in the 1960s and 1970s, as well as in recordings made by other investigators. Although Temiar and Batek tunes belong recognisably to the same melodic family, the differing organisational patterns of their performances produce quite distinct auditory impressions.

The (formerly) swidden-farming Temiars build their performances out of a fairly strict responsorial canon between the lead singer and a unison women’s chorus (Figure 1), in which the latter ‘pounce’ (bəluh in Temiar) before the former has finished his (occasionally, her) verse. The regular periods of counterpoint that this produces (such as between the halāˀ and chorus lines in Figure 2)7 are greatly valued by the Temiars as a re-presentation of the dialecticism that colours all of their social life—and especially their religion—based on the interplay between village-level solidarity and a strict regard for individual autonomy.8 This feature can be heard in an extract from my recordings. (To play this and the other soun samples, you may need to copy the URL into your Internet browser):

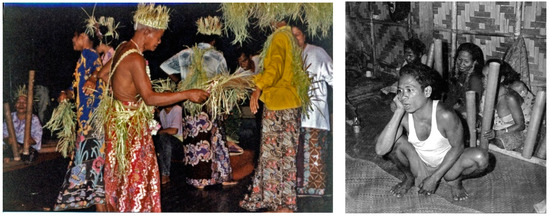

Figure 1.

Temiar song performances. (Left) Abilem at the University of Malaya (1995); (Right) Salleh, Kuala Humid, Kelantan (1964).

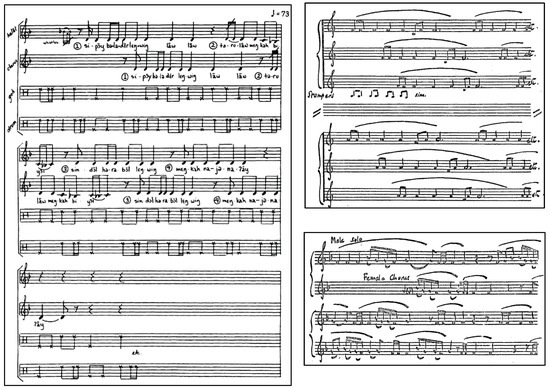

Figure 2.

Transcriptions of Temiar canonic overlap. (Left) From a Temiar song performance by Abilem Lum, as recorded and transcribed by Marina Roseman (1984, p. 423). Halāˀ is the lead singer, goh [properly gɔɔh] are the chorus’s bamboo-tube beaters. (Right) Portions of Temiar songs (1962) from Kuala Kenrap, Kelantan, as recorded and transcribed by Jack Dobbs (1972, pp. 39–40).

Sound sample 1: https://soundcloud.com/user-66231241-911333342/benjamin-example-2-temiar-song (accessed on 27 August 2022) Temiar recording of ‘Maɲak flower’ sung by Taaˀ Cəkolaag and chorus at Lambok (Kelantan) on 15 May 1970.

A short sample of the same canonic homophony can also be heard online in the Temiar song ‘Alus (Song of the Tiger)’, taken from an historic field recording made by Radio Malaya in northern Perak on 7 December 1941, just one day before the Japanese invasion began not far away:

Sound sample 2: Track 205 of https://folkways.si.edu/temiar-dream-songs-from-malaya/islamica-psychology-health-world/album/smithsonian (accessed on 27 August 2022).

The contrasting Batek performance (Figure 3) on the other hand, though also responsorial, is wildly heterophonic, to the extent of being individualistically undisciplined, producing the overall effect of a disordered hum. This can be heard in my recording of ‘Yãh [tiger]’, sung by Kacaŋ Kapɛs at Pos Aring (Kelantan) on 22 April 1970:

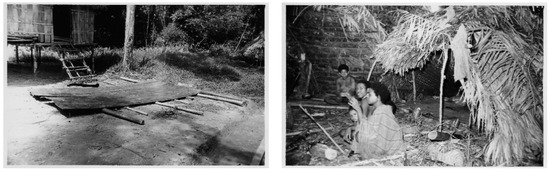

Figure 3.

Bateks, Ulu Aring, Kelantan, April 1970. (Left) Flattened tree-bark resonator ready for a night-time song performance. (Right) Family in their windscreen dwelling.

Sound sample 3: https://soundcloud.com/user-66231241-911333342/benjamin-example-1-batek-d-1-2 (accessed on 27 August 2022).

This manner of performance accords with the people’s minimalist social formation, in which conjugal-family groups can split off at a moment’s notice from the larger group to go foraging on their own, in a pattern that has been well described more generally in the literature on the nomadic hunter-gatherers of the Malay World.9

Other, more socially differentiated, Orang Asli populations prefer to wait until the lead singer has completed the verse before ‘answering’ it. A Temiar respondent once described this pattern to me (using a Malay phrase) as tərlewat ‘later, behind (in time)’, which he acknowledged as being more common among their southern neighbours the Semais, who (he said, in Malay) mesti tunggu ‘must wait’. This ‘waiting’ is also a feature of so-called Melayu-style trancing as performed by the Temiars themselves, in contrast to the more usual overlapping-canon just described, which my respondent characterised (again, in Malay) as sambung-sambung ‘all joined up’. This lack of canon in favour of simple lead-and-response accords with the higher degree of social differentiation found in those populations (cf. Benjamin 2014a, pp. 271–74). It sometimes proceeds all the way to the complete suppression of the chorus, leaving just a solo singer, as among the Mah Meri mentioned at the end of this article.10

Abilem is the singer transcribed by Roseman in Figure 2.

3. Performance Manner

In the Malay World, differences in performance manner relate primarily to the distinction between elites and peasants on the one hand and tribespeople on the other. The higher-ranking Orang Melayu typically favour a richly melismatic and vibrato-laden style of performance that places at least as much emphasis on the decorated transitions between the primary melody notes as on the main notes. This is overtly recognised by Melayu musicians, as shown by the range of words they have used when talking with me about their melismatic practices:11

- Nada-nada hiasan ‘decorated notes’

- Patah lagu ‘song-fracturing’

- Cengkok Melayu ‘Malay(-style) twisting’

- Grenek, menggerenek/renek, renek-renek, merenek/gereneh, menggereneh ‘quavering’

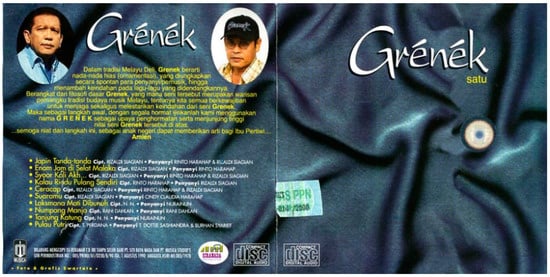

Melayu musicians are clearly well aware of the role of such decorative elaboration in signifying the Melayuness of their music. The last of the listed terms, grenek and its variants, was even chosen as the title of a commercial audio CD (Figure 4) produced by a group of Melayu musicians from Medan (North Sumatra) directed explicitly—according their sleeve-note (as translated below)—at celebrating their Melayu-ness:

Grénék: In Deli-Malay tradition, Grenek means ‘ornamentation’ (nada-nada hias), which is applied in a spontaneous manner by singers and musicians, to increase the beauty of the songs they sing. Arising out of the basic philosophy of Grenek, according to which this art displays the traditional heritage of Malay musical culture, we are all assuredly charged with the duty of safeguarding the beauty of the art of Grenek. As a first step, with all respect, permit us to use the name G R E N E K as a means of paying respect and raising high the quality of the art of Grenek, Amen.12

Figure 4.

Cover of Grénék Satu audio CD.

This highly decorated style is also true, of course, of the Muslim call to prayer and Quranic chant. These religious activities are not uniquely Melayu, but the manner in which they are performed merges into the aesthetic exhibited in the rest of Melayu musical performance. So why do Orang Melayu place such a high value on performing in such a highly decorated manner? As I have shown in detail elsewhere (Benjamin 2019b, pp. 95–99), this relates directly to a general concern in Melayu culture and language for the marking of transition—things that change, rather than things that stay the same. This leads to a markedly ‘searching’ mode of action in such different domains of life as religion, food behaviour, social organisation, language, vernacular architecture, and of course the Islamic life-course. Here, I add only that it applies also to the favoured melismatic style of performance, as if each note were searching for the next—is it above or is it below?—thereby placing great emphasis on the transition between them. This can be heard in a field recording I made in 1990 of the ghazal song ‘Gunung Bentan’ at a wedding on Pulau Penyengat, widely recognised as a major historical site of Melayu cultural production. The singer, Raja Khadijah, belongs to the aristocratic section of the island’s population (Wee 2019, pp. 173–85).

Sound sample 4: https://soundcloud.com/user-66231241-911333342/benjamin-example-6-gunung (accessed on 27 August 2022).

Ghazal performance circumstances are clearly secular, but the embedded transition-emphasising view of the world carried by the associated performance manner underlies both the secular and the clearly ‘religious’ domains. A superb example of the same style, extracted from a commercial recording, can be heard here:

Sound sample 5: https://soundcloud.com/user-66231241-911333342/benjamin-example-9-rosiah-chik (accessed on 27 August 2022).

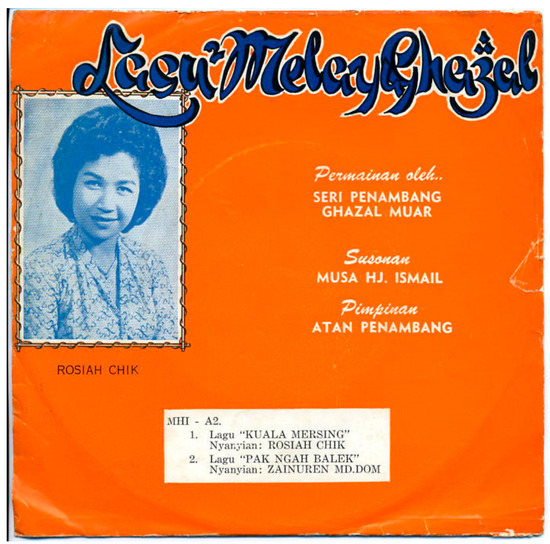

This performance of the song ‘Kuala Mersing’ by Rosiah Chik, accompanied by the Sri Penampang Ghazal Muar ensemble, comes from a 7-inch 45-rpm gramophone record entitled Lagu2 Melayu Ghazal, issued in Johor in the 1960s. The song is secular, but the style is easily linkable to Islam, both by labelling it ghazal and by the faux-Arabic lettering on the record’s sleeve (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Cover of Rosiah Chik’s Lagu2 Malayu Ghazal, 7-inch 45rpm gramophone record.

On the other hand, the Malay-speaking tribespeople (who are Malays, but not Muslims or Orang Melayu in the narrower sense) typically employ a stark, raw-sounding undecorated style, with the movement between the main notes uninterrupted by any melismatic elaboration. (Among the tribespeople, there is no significant difference in this regard between the hunter-gatherers and the more numerous sedentary swiddeners and forest traders.) In one such performance, recorded by Philip Yampolsky in 1994, Orang Akit people from an island just off the east coast of Sumatra perform their version of the Melayu song ‘Serampang Laut’ completely undecorated. This can be heard here:

Sound sample 6: Track 115 at https://folkways.si.edu/music-of-indonesia-vol-11-melayu-music-of-sumatra-and-the-riau-islands/islamica-world/album/smithsonian (accessed on 27 August 2022).

The singers are—or were until recently—marginally hunter-gatherers, as they are members of a strand-dwelling subgroup of the Orang Suku Laut who formerly moved around on house-rafts along the shores from which they foraged.

The tribal Malays mobilise the plainness of their performance manner to differentiate between themselves and the ever-present Orang Melayu. Given that their first languages are actually local-Malay dialects, this implies that the undecorated tribal manner constitutes the musical expression of a process of dissimilation from within what might otherwise historically have become the same overall population. This is probably mutual, with the elaborated Islamic manner of the neighbouring Orang Melayu serving partly as a means of protection against the feared reabsorption by their less hierarchical tribal neighbours. Thus, there is a clear power dimension embedded in the stark difference between these two contrasted manners of performance. The Melayu performance manner indicates how difficult it would be for those lower in the hierarchy to ascend to the elite and Muslim level. The Orang Laut manner, on the other hand, indicates their resistance as animist tribespeople to any such assimilation.13

4. Tribal Musicians as Entertainers

These distinctions spill over into the (formerly) favoured styles employed in performances intended as entertainment. Among the tribal populations of the Malay World, the maritime and coastal Orang Laut in particular have specialised in providing musical and dance entertainment for sedentary Orang Melayu.14 Even here, their starkly unembellished performance manner is well to the fore, with both the singing and violin (biola) playing left undecorated—deliberately so, one might say—and very direct. This typically involved social dancing of the ronggeng or joget types (ultimately of Portuguese origin), which depended on women and men dancing together, an activity typically frowned on as un-Islamic by many Orang Melayu. An example can be heard in a ronggeng performance from southern Thailand, excerpted from a rare privately made audio CD titled Rong Ngang Song of Koh Lanta (‘Ronggeng songs of Lanta Island’):

Sound sample 7: https://soundcloud.com/user-66231241-911333342/benjamin-example-7-citeepayong (accessed on 27 August 2022).

In this very roughly recorded example made in 2001, the Melayu song ‘Siti Payong’ is performed by Sonah Changnam, a member of the Urak Lawoi’ (‘Orang Laut’) population, at the northernmost end of the Orang Laut range. Although these (former) strand-dwellers now live on some of Thailand’s Andaman Sea islands, they probably originated from the Sumatran east coast just over a century ago.

Ronggeng and joget were also features of life in the Riau Islands of Indonesia, just south of Singapore, where some of the people formerly made money as entertainers for nearby Orang Melayu. In 2013, I recorded the remnants of such activity in an Orang Suku Laut settlement on Pulau Nanga, off Galang Baru in the Riau Islands, whose womenfolk had formerly performed as singers and dancers at Melayu celebrations. An extract from one of the audio tracks, Ainon singing ‘Tanjung Katong’, can be heard here:

Sound sample 8: https://soundcloud.com/user-66231241-911333342/benjamin-example-10-ainon (accessed on 27 August 2022).

Videos of this and related performances by her neighbours show the dance movements that accompanied such singing. Unfortunately, the performances were a shadow of their presumed former self, as they lacked instrumental accompaniment. Poverty and the falling away of feudal-type social relations with their Orang Melayu neighbours had led them to sell their violins, gongs and drums. Moreover, the practice of hiring themselves to entertain Orang Melayu appears to have hastened the extinguishing of any earlier distinctive musical tradition (but see Chou and Kartomi 2019).

5. Music and Religion in the Malay World

The vocal music of the various Orang Asli populations is inherently religious, being employed as part of the rituals through which they communicate directly with non-empirical subjectivities. The music of the other populations also spills over into the religious domains, but this is too large a topic to elaborate on here. Instead, I conclude by mentioning just two highly contrasting examples in which religion is implicit.

The first of these is a (former-)tribal performance, which I videoed in Singapore when a troupe of Mah Meri Orang Asli15 from the Selangor coast took part in the Esplanade’s A Tapestry of Sacred Music festival in 2016. The performance was a slightly choreographed version of the mediumistic rituals that the Mah Meri perform in their home village. As is evident from Sound sample 9, they employed the same undecorated direct manner of performance, both in the singing and violin playing, that can be heard in the tribal recordings already referred to:

Sound sample 9:https://soundcloud.com/geoffrey-benjamin/benjamin-mah-meri-spirit-dance-extracted-audio-mvi-2367 (accessed on 27 August 2022).

Although the Mah Meri language is Austroasiatic, they are now coastal dwellers living closer to Orang Melayu than to other Aslian-speakers, and appear to have assimilated to the usual Orang Laut manner, while still employing bamboo stampers.

At the other end of the scale is a more explicitly religious item performed in a highly melismatic style that even outdoes most Muslim calls to prayer. The text is from Raja Ali Haji’s moralising Gurindam Duabelas verses composed and printed on Pulau Penyengat in 1847, which are explicitly Islamic in reference.

Sound sample 10: https://bridges.monash.edu/articles/media/Dwi_Saptarini_Adi_Supriyadi_Gurindam_Duabelas_Monash_/7803209 (accessed on 27 August 2022).

Although this performance was recorded at a conference in Melbourne (2015), I had also previously heard the same musicians perform it on home ground in Tanjungpinang. In this performance, the verses are provided with a new setting by Adi Supriyadi in a recomposed elite Melayu style employing a range of traditional Melayu melismatic tropes. Adi himself provides the sole accompaniment, on violin, to the singing of Dwi Sapartini.

6. Conclusions

In this very brief account, I have provided examples of the ways in which musical and associated performances among various populations in the Malay World serve to embed key aspects of their societal and cultural imperatives, simultaneously religious (in the broad sense) and secular, in a manner that leaves them directly felt, rather than expressible as overtly teachable ‘values’.16

Funding

This research was funded in part at various times by the Royal Anthropological Institute, (London) and by the Centre for Liberal Arts and Social Sciences (CLASS, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | ‘Endogenous’ here refers to cultural traditions (such as the various Orang Asli—that is, Malaysian Aboriginal—religions) that developed within the places under discussion, rather than those (such as Islam) that were originally imported from elsewhere. I use ‘endogenous’ intentionally to avoid the term ‘indigenous’, which is usually concerned more with issues of identity and politics than of cultural content. |

| 2 | For further discussion of this approach, see Benjamin (2014a, 2014b, 2019b). |

| 3 | As used here, ‘Melayu’ refer to the centralised, highly assimilable cultural tradition of the Muslim ‘Malays proper’. ‘Malay’ or ‘Malayic’, on the other hand, refers also to some Malay-speaking, historically non-Muslim, tribal populations whose kinship organisation falls into the same overall (‘Malayic’) pattern as that of the Melayu populations. For further discussion, see Benjamin (2002, pp. 10–12, 26–28). |

| 4 | The latter speak some twenty languages belonging to a well-defined subgroup of Austroasiatic known as Aslian, itself divided into a further four top-level sub-divisions. |

| 5 | This usage of ‘tribal’ and ‘tribespeople’ is argued for in Benjamin (2002, pp. 12–17). |

| 6 | Hocketing—the sharing of a single melody between two or more alternating voices such that one sounds while the other rests—in tribal-Malay performance is briefly mentioned in Benjamin (2019b, pp. 109–11). |

| 7 | Writing about Paul Schebesta’s 1920s field recordings of Temiar music, Hornbostel (1926, p. 277) wondered with surprise whether the simultaneously sounded thirds that sometimes resulted might represent the beginnings of harmony. Dobbs (1972, p. 35), in an excellent detailed study that appears to have gone completely unnoticed, remarks ‘This may have had its origins in chance; it has now become a tradition.’ In my view, any such acceptance would have occurred precisely because of the dialectical orientation that permeated the Temiars’ way of life. |

| 8 | On Temiar dialecticism, see Benjamin (2014a) with regard to their religion, Benjamin (2012, 2014b) on language, and Benjamin (forthcoming, especially Chapters 7 and 8) on their pattern of social organisation. Jennings (1995) and Roseman (1984, 1991) have provided much further ethnographic detail on how Temiar dialecticism is manifested in practice. |

| 9 | However, increasing sedentisation among these former nomads appears to be associated with a change in performance organisation, towards a more chorus-like pattern, similar to that of the Temiars. |

| 10 | Even the Temiars, when performing in ‘Melayu’ style, follow this pattern too. As Roseman has remarked (Roseman 1984, p. 427), this implies a differentiation into leader and follower, performer and audience, as befits the varyingly ranked character of the Malayic social formations. Conversely, in some Melayu(-style) performances among the Orang Asli, there may be just a unison chorus, with no solo voice. |

| 11 | Of these, patah lagu is reported by Nurmaisara et al. (2011, p. 46) as the preferred term, alongside such others as lenggok ‘swaying sideways’, bunga melodi ‘flower on the melody’, or penyedap lagu ‘song flavourer’. In a richly illustrated analysis, however, Nik Shareena Rosny (2018, pp. 29–36, 71–114) shows that these and other such terms are not synonyms. For example, she effectively associates patah lagu with phrasing articulation, cengkok with changing-notes involving intervals of a third, grenek with various kinds of trill and turn, and bunga with short grace-notes. |

| 12 | There is also a scholarly journal bearing the title Grenek: Jurnal Seni Musik/Grenek Music Journal, published by the Faculty of Language and Arts at Universitas Negeri Medan in North Sumatra, ISSN: 2579-8200 (online), 2301-5349 (print). |

| 13 | However, there are key differences in this regard between the Malayic-speaking and the upland Aslian-speaking tribespeople. The latter in their musical performance manners do not necessarily exhibit the ‘tribal’ manner just outlined, presumably because they clearly belong linguistically and culturally to non-Melayu, or even non-Malayic, traditions. Their musical performance styles are sufficiently different in both organisation and manner—which is sometimes also quite melismatic—as to preclude any need to further emphasise their differences from the Melayu tradition. |

| 14 | For an account of such itinerant performances along and upriver from the east coast of Sumatra in the mid-20th century, see Chou and Kartomi (2019, pp. 130–32). |

| 15 | The Mah Meri—which means ‘Forest People’ in their own Southern Aslian language—are also known as Besisi, Betisé’, Betisék, and other variant spellings. |

| 16 | This approach is argued for at greater length in Benjamin (2019b). |

References

Primary Sources

Recordings:Grénék Satu. 2000. Audio Compact Disk Album of Modern Malay Songs from Deli (Medan). Performed by Rinto Harahap and Others. SRN CD 003. Jakarta: Siti Raya Nada.Lagu2 Melayu Ghazal. n.d. Rosiah Chik & Seri Penampang Ghazal Muar. Monophonic 45 rpm Single-Play Gramophone Record. Muar: Maharani Store, MHI-A2.Melayu Music of Sumatra and the Riau Islands: Zapin, Mak Yong, Mendu, Ronggeng. 1996. Audio compact disk album, with detailed notes. Volume 11 in the series Music of Indonesia. Recorded by Philip Yampolsky. SF CD 40427. Washington: Smithsonian Folkways.Rong Ngang Song of Koh Lanta. 2001. Audio Compact Disk Album to Celebrate Amphur Koh Lanta 100th Anniversary, 2001. Krabi: Rong Ngang Descend Educational Andaman Coast.Secondary Sources

- Benjamin, Geoffrey. 2002. On being tribal in the Malay World. In Tribal Communities in the Malay World: Historical, Social and Cultural Perspectives. Edited by Geoffrey Benjamin and Cynthia Chou. Leiden: International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS), Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS), pp. 7–76. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Geoffrey. 2012. Deponent verbs and middle-voice nouns in Temiar. In Austroasiatic Studies: Papers from ICAAL4 (=Mon-Khmer Studies). Edited by Sophana Srichampa and Paul Sidwell. Special Issue No. 2. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics E-8, pp. 11–37. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Geoffrey. 2014a. Temiar Religion, 1964–2012: Enchantment, Disenchantment and Re-Enchantment in Malaysia’s Uplands. With a Foreword by James C. Scott. 68 Figures. 470 Pages. Singapore: NUS Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Geoffrey. 2014b. Aesthetic elements in Temiar grammar. In The Aesthetics of Grammar: Sound and Meaning in the Languages of Mainland Southeast Asia. Edited by Jeffrey Williams. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 36–60. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Geoffrey. 2019a. Malay art music composers and performers of Tanjungpinang and Pulau Penyengat. In Performing the Arts of Indonesia: Malay Identity and Politics in the Music, Dance and Theatre of the Riau Islands. Edited by Margaret J. Kartomi. Copenhagen: NIAS Press, pp. 279–302. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Geoffrey. 2019b. Music and the cline of Malayness: Sounds of egalitarianism and ranking. In Hearing South East Asia: Sounds of Hierarchy and Power in Context. Edited by Nathan Porath. Copenhagen: NIAS Press, pp. 87–116. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Geoffrey. Forthcoming. Between Isthmus and Islands: An Anthropological History of the Malay World. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS).

- Benjamin, Geoffrey, and Cynthia Chou, eds. 2002. Tribal Communities in the Malay World: Historical, Social and Cultural Perspectives. Leiden: International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Blacking, John. 1974. How Musical is Man? Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, Cynthia, and Margaret Kartomi. 2019. Sounds in the water world of the Orang Suku Laut in the Riau islands of Indonesia. In Hearing South East Asia: Sounds of Hierarchy and Power in Context. Edited by Nathan Porath. Copenhagen: NIAS Press, pp. 117–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs, Jack P. B. 1972. Music and Dance in the Multi-Racial Society of West Malaysia. MPhil thesis, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, London, UK; 559p. Available online: https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/28596 (accessed on 27 August 2022).

- Hornbostel, E. Von. 1926. Die Musik der Semai auf Malakka. Anthropos 21: 277. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, Sue. 1995. Theatre, Ritual and Transformation: The Senoi Temiars. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kolinski, Mieczysław. 1930. Die Musik der Primitivstämme auf Malaka und ihre Beziehungen zur samoanischen Musik (aus dem staatlichen Phonogramm-Archiv Berlin). Anthropos 25: 585–648. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, Anthony C. 2016. Kerajaan: Malay Political Culture on the Eve of Colonial Rule, 2nd ed. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. Petaling Jaya: Strategic Information and Research Development Centre (SIRDC). First published 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Nik Shareena Rosny, Mohd Rosly. 2018. Kajian Ornamentasi Dalam Muzik Melayu Asli: Permainan Violin Gaya Hamzah Dolmat. Mater’s Performing Arts thesis, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 150p. Available online: http://studentsrepo.um.edu.my/id/eprint/8607 (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Nurmaisara, Za’ba, Nursuriati Jamil, Siti Salwa Salleh, and Nurulhamimi Abdul Rahman. 2011. Investigating ornamentation in Malay traditional, Asli music. In Recent Researches in Chemistry, Biology, Environment and Culture. Edited by Vincenzo Niola and Ka-Lok Ng. Montreux: WSEAS Press, pp. 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Perlman, Mark. 1998. The social meanings of modal practices: Status, gender, history, and pathet in Central Javanese music. Ethnomusicology 42: 45–80. [Google Scholar]

- Roseman, Marina. 1984. The social structuring of sound: The Temiar of Peninsular Malaysia. Ethnomusicology 28: 411–45. [Google Scholar]

- Roseman, Marina. 1991. Healing Sounds from the Malaysian Rainforest: Temiar Music and Medicine. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wee, Vivienne. 2019. Kinship among Penyengat musicians: The jiwa seni of Raja Khadijah, Tengku Fadillah, their forebears and descendants. In Performing the Arts of Indonesia: Malay Identity and Politics in the Music, Dance and Theatre of the Riau Islands. Edited by Margaret J. Kartomi. Copenhagen: NIAS Press, pp. 173–98. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).