Educational Effectiveness of Catholic Schools in Poland Based on the Results of External Exams

Abstract

:1. Introduction

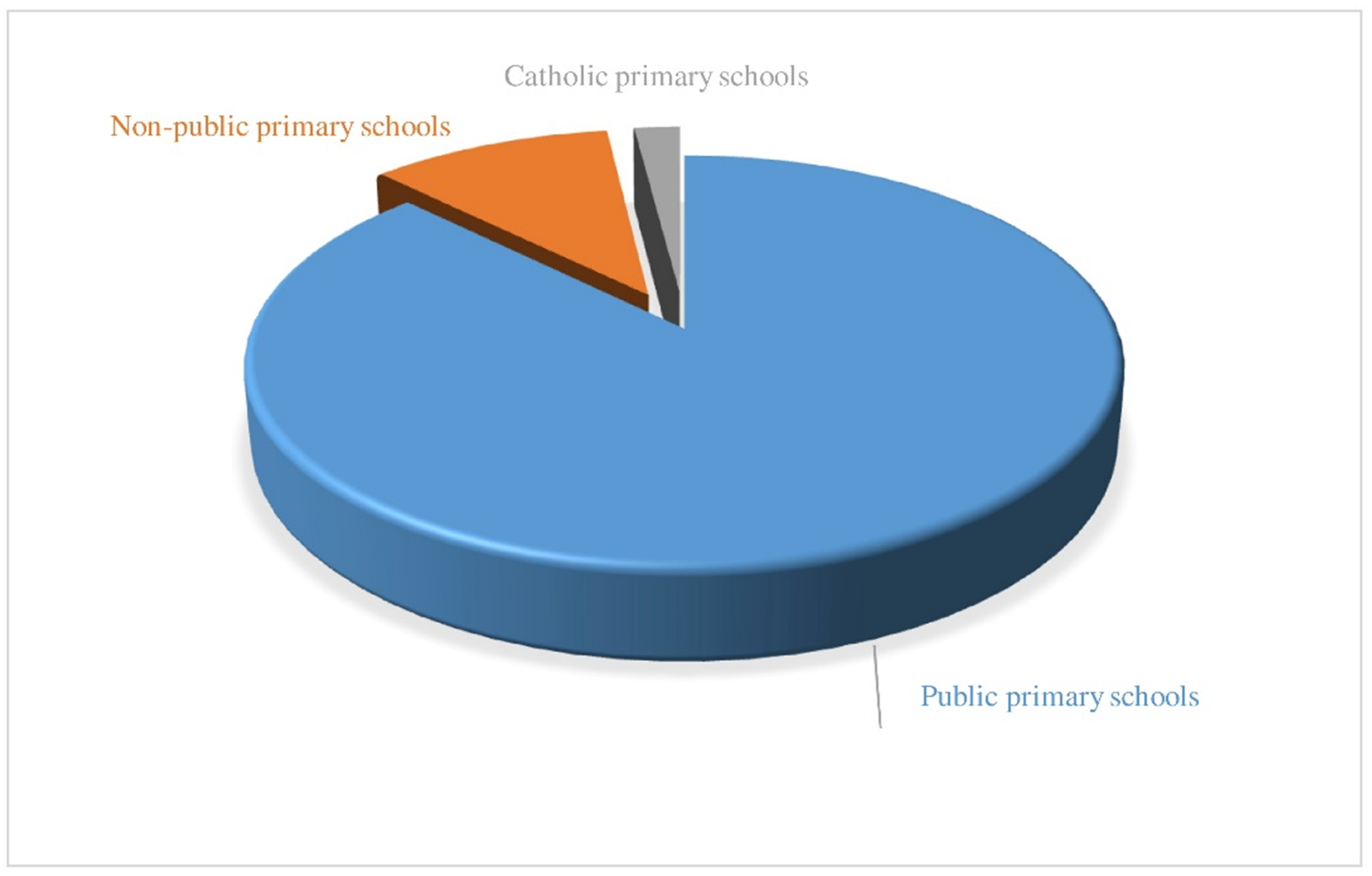

2. The Place of Catholic Schools in the Polish Education System

3. Primary Schools

4. Comprehensive High Schools (Licea Ogólnokształcące)

5. Conclusions

- Over the last 30 years, Catholic schools have found their place in Polish education, significant enough to be included in analyses of the current state and in forecasting future data.

- At the primary school level, the didactic effectiveness of Catholic schools is much higher than average, although they are surpassed in this respect by the best non-public primary schools run by other entities.

- At the upper secondary and secondary school levels, the teaching effectiveness of Catholic schools is equal to good public schools. At this level, non-public schools, including Catholic ones, do not dominate the top rankings. Here there are mainly public high schools, which are in the majority among schools that are successful in national and international competitions.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In this study, non-public schools will be defined as school governing bodies which are not local government units or central administration bodies. Some such institutions are classified as public schools, but for the purposes of this analysis, the type of legal entity running the school is decisive. |

References

- Aigrain, René. 1935. Les Universites Catholiques. Paris: Publisher A. Picard. [Google Scholar]

- Centralna Komisja Egzaminacyjna (CKE). 2021a. Wstępne informacje o wynikach egzaminu ósmoklasisty 2021. Available online: https://cke.gov.pl/images/_EGZAMIN_OSMOKLASISTY/Informacje_o_wynikach/2021/20210701_informacja_wstepna_E8.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Centralna Komisja Egzaminacyjna (CKE). 2021b. Wyniki, sprawozdania. Available online: https://cke.gov.pl/egzamin-maturalny/egzamin-maturalny-w-formule-2015/wyniki/ (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Cichosz, Wojciech. 2007. De l’école chrétienne á l’école laïque. Studia Gdańskie 21: 377–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cichosz, Wojciech. 2008. Historische Wurzeln, das heutige Bild und Substanz der katholischen Schule in Polen. Studia Gdańskie 23: 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Cichosz, Wojciech. 2010. Pedagogia wiary we współczesnej szkole katolickiej. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo TYPO2. [Google Scholar]

- Cichosz, Wojciech. 2012. Biblijne wychowanie parenetyczne. Od pedagogiki do pedagogii. Studia Katechetyczne 8: 243–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cichosz, Wojciech. 2016. Szkoła katolicka środowiskiem wychowania młodzieży w wierze: Od nauczania do katechezy. In Polska krajem misyjnym? 1050 lat chrześcijaństwa w Polsce. Edited by Tomasz Wielebski. Warszawa: Warszawskie Studia Pastoralne, pp. 265–86. [Google Scholar]

- Cichosz, Wojciech. 2019. Wychowanie integralne. Praktyczna recepcja Gimnazjum w Zespole Szkół Katolickich im. św. Jana Pawła II w Gdyni. 1992–2019. Pelplin: Wydawnictwo Bernardinum. [Google Scholar]

- Cichosz, Wojciech. 2020. Anthropological determinansts of religious education. In Religious Pedagogy. Edited by Zbigniew Marek and Anna Walulik. Krakow: Ignatianum University Press, pp. 345–65. [Google Scholar]

- d’Irsay, Stephen. 1933. Histoire des universités françaises et étrangères. Paris: Auguste Picard. [Google Scholar]

- EB. 2021a. Liczba uczniów i szkół w Polsce. Available online: https://www.edubaza.pl/s/3468/80886-Liczba-uczniow-w-Polsce.htm (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- EB. 2021b. Szkoły Podstawowe w Polsce. Available online: https://szkolypodstawowe.edubaza.pl (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Edukacyjna Wartość Dodana (EWD). 2013. Available online: http://ewd2013.ibe.edu.pl/faq-ewd/#:~:text=Edukacyjna%20warto%C5%9B%C4%87%20dodana%20definiowana%20jest%20jako%20przyrost%20wiedzy,wynikami%20uzyskanymi%20na%20egzaminie%20zewn%C4%99trznym%20przez%20jej%20uczni%C3%B3w (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Gleeson, Jim. 2015. Critical Challenges and Dilemmas for Catholic Education Leadership Internationally. International Studies in Catholic Education 7: 145–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gov. 2020. Szkoły i uczniowie w roku szkolnym 2020/2021 według organów prowadzących i województw, stan na 30 września 2020 r. Available online: https://dane.gov.pl/pl/dataset/212/resource/31168/table?page=1&per_page=20&q=&sort= (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Kongregacja do spraw Wychowania Katolickiego. 2009. Religijny wymiar wychowania w szkole katolickiej. In Służyć wzrastaniu w prawdzie i miłości. Wybór dokumentów Kościoła na temat szkoły katolickiej i wychowania. Edited by Janusz Poniewierski. Kraków: Rada Szkół Katolickich, pp. 431–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kuźma, Józef. 2011. Nauka o szkole. Studium Monograficzne. Zarys koncepcji. Kraków: Oficyna Wydawnicza Impuls. [Google Scholar]

- Maj, Adam. 2002. Szkolnictwo katolickie w III RP (1989–2001). Status i rozwój w okresie przemian oświatowych. Warszawa: Oficyna Wydawniczo-Poligraficzna “Adam”. [Google Scholar]

- Mąkosa, Paweł. 2020. St. John Paul II and Catholic education. A review of his teachings: An essay to inspire Catholic educators internationally. International Studies in Catholic Education 12: 218–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okręgowe Komisje Egzaminacyjne (OKE). 2021. Available online: https://www.cke.gov.pl/komisje-egzaminacyjne (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Perspektywy. 2018. Ranking liceów ogólnokształcących 2018. Available online: https://licea.perspektywy.pl/2018/ranking/ranking-liceow-ogolnoksztalcacych-2018?strona=1 (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Perspektywy. 2019. Ranking liceów ogólnokształcących 2019. Available online: https://licea.perspektywy.pl/2019/ranking/ranking-liceow-ogolnoksztalcacych-2019 (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Perspektywy. 2020. Ranking liceów ogólnokształcących 2020. Available online: https://licea.perspektywy.pl/2020/rankings/ranking-glowny-liceow (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- Perspektywy. 2021a. Ranking liceów ogólnokształcących 2021. Available online: http://licea.perspektywy.pl/2021/rankings/ranking-glowny-liceow (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Perspektywy. 2021b. Ranking maturalny liceów ogólnokształcących 2021. Available online: https://licea.perspektywy.pl/2021/rankings/ranking-maturalny-liceow (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Perspektywy. 2021c. Ranking Szkół Olimpijskich 2021. Available online: https://licea.perspektywy.pl/2021/rankings/ranking-szkol-olimpijskich (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Perspektywy. 2021d. Ranking szkół olimpijskich 2021–metodologia. Available online: https://licea.perspektywy.pl/2021/methodology/ranking-szkol-olimpijskich-2021-metodologia (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Perspektywy. 2022a. Metodologia. Available online: https://2022.licea.perspektywy.pl/methodology (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Perspektywy. 2022b. Ranking Szkół Olimpijskich 2022. Available online: https://licea.perspektywy.pl/2022/rankings/ranking-szkol-olimpijskich (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Rada Szkół Katolickich (RSK). 1999. Informator adresowy o szkołach katolickich. Warszawa: Rada Szkół Katolickich. [Google Scholar]

- Rada Szkół Katolickich (RSK). 2022. Baza szkół. Available online: https://rsk.edu.pl./baza-szkol/ (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Rynio, Alina. 2017. Tradycyjne i współczesne środowiska wychowania chrześcijańskiego. In Septuaginta pedagogiczno-katechetyczna. Księga jubileuszowa dedykowana Księdzu Profesorowi dr. hab. Zbigniewowi Markowi SJ w siedemdziesiątą rocznicę urodzin pod redakcją naukową Anny Walulik CSFN i Janusza Mółki SJ. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Ignatianum, pp. 369–87. [Google Scholar]

- Rządowy projekt ustawy–Prawo oświatowe (PUPO). 2016. Available online: https://www.sejm.gov.pl/sejm8.nsf/PrzebiegProc.xsp?nr=1030 (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- UoSO. 1991. Ustawa z dnia 7 września 1991 r. o systemie oświaty. Dziennik Ustaw Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej 95: 425. [Google Scholar]

- UPO. 2021. Ustawa z dnia 14 grudnia 2016 r. Prawo oświatowe. Dziennik Ustaw Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, 1082. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Number of Schools by Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Junior High School | Professional | High School | |

| 1989 | – | – | 3 | 21 |

| 1993 | 18 | – | 6 | 54 |

| 1999 | 57 | 63 | 37 | 119 |

| 2001 | 71 | 105 | 33 | 141 |

| 2003 | 96 | 140 | 25 | 144 |

| 2004 | 100 | 143 | 27 | 143 |

| 2020 | 259 | – | 23 | 144 |

| Year | Number of Catholic Schools | Number of Students in Catholic Schools | Total Number of Students in Poland | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001/2002 | 400 | 50,000 | 6,800,000 | 0.74% |

| 2005/2006 | 451 | 51,000 | 6,550,013 | 0.78% |

| 2010/2011 | 515 | 57,000 | 5,505,946 | 1.03% |

| 2015/2016 | 608 | 66,321 | 5,198,793 | 1.28% |

| 2016/2017 | 610 | 66,365 | 4,952,219 | 1.34% |

| 2017/2018 | 527 | 67,589 | 4,905,435 | 1.38% |

| 2018/2019 | 467 | 70,556 | 4,904,101 | 1.44% |

| 2020/2021 | 487 | 72,469 | 4,931,461 | 1.47% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cichosz, W. Educational Effectiveness of Catholic Schools in Poland Based on the Results of External Exams. Religions 2023, 14, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010005

Cichosz W. Educational Effectiveness of Catholic Schools in Poland Based on the Results of External Exams. Religions. 2023; 14(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleCichosz, Wojciech. 2023. "Educational Effectiveness of Catholic Schools in Poland Based on the Results of External Exams" Religions 14, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010005

APA StyleCichosz, W. (2023). Educational Effectiveness of Catholic Schools in Poland Based on the Results of External Exams. Religions, 14(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14010005