1. Introduction

Extensive research has been conducted to analyse theories on intergroup relations and prejudiced attitudes towards religious groups, consistently revealing that tolerance and harmonious interactions between groups, especially through positive contact, foster an atmosphere of respect among various religious communities (

Paluck et al. 2019;

Pettigrew and Tropp 2013). Conversely, problematic intergroup relationships characterised by experiences or perceptions of discrimination negatively impact intergroup attitudes (

Branscombe et al. 1999;

Craig and Richeson 2012;

Dion 2002).

The study of interreligious relations as a research field focuses on examining how the interpretation and practice of religious beliefs contribute to prejudice against external groups. For example,

Allport (

1966) emphasised the importance of understanding how social and cultural contexts shape religious beliefs and influence prejudice. Nevertheless, the author recognised that religious prejudice is not directly linked to the religion of out-groups but rather to the interpretation and practice of religious beliefs.

De Wenden (

1988) further delved into the factors influencing religious tolerance and prejudice to comprehend the underlying reasons for tolerant or prejudiced behaviours. Promoting interreligious tolerance is suggested as an effective approach to reducing intolerance.

This paper adopts a deterministic approach to analyse attitudes towards religious groups, through a suitable methodology for studying individual attitudes (

Martín and Indelicato 2022,

2023), i.e., the Fuzzy-Hybrid TOPSIS, that will be adopted to develop synthetic indicators that we define as Attitudes Towards Religions (ATR).

Through employing deterministic tools that are not commonly utilised in the field, this paper complements and extends existing studies (

Kanol 2021). Thus, this empirical application will serve as a valuable guide for the application of these novel quantitative methods to the social sciences, contributing to the expansion of the literature on studies of Religious Tolerance.

This paper continues in the next sections by illustrating the theoretical background (

Section 2), the dataset used in this study (

Section 3), the adopted methodology (

Section 4), and the findings (

Section 5). Finally, in the last sections (

Section 6 and

Section 7), discussions and overall conclusions are provided.

2. Attitudes towards Religious Groups

Religion is traditionally considered a moral foundation, guiding principles of right and wrong with divine authority. The principle of treating others as one would like to be treated, exemplified in Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37) (

Preston et al. 2010), is taught by most major world religions. However, the role of religion is paradoxical, as highlighted by

Allport (

1954). On the one hand, religion promotes mutual help, love for peace, and tolerance. On the other hand, it has also been used as a catalyst for hostility, violence, and even wars (

Coward 1986).

The academic literature consistently highlights the complex and contradictory nature of religion’s influence. Several studies have revealed a positive connection between religiosity and pro-social attitudes and behaviours (

Oviedo 2016). Believers often display higher levels of cooperation compared to atheists (

Yilmaz and Isler 2019). However, it is important to note that religious individuals have also exhibited increased animosity towards those outside their religious community, unlike non-believers (

Batson et al. 1993). For example, the literature suggests that Christian believers tend to demonstrate greater hostility towards non-believers than vice versa (

Kanol 2021).

Islam (

2020) emphasizes the importance of religious communities living together harmoniously. Harmony enables mutual respect, cooperation, and even love among religious groups. With tolerance, establishing mutual love, harmony, and respect becomes possible. Tolerance is key to fostering love, respect, and cooperation (

Davis 2002). Scholars have also examined the role of religion in problematic attitudes between groups. It has been acknowledged that religious beliefs can also ignite intolerance. According to

Allport and Ross (

1967), religiosity can be intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic religiosity promotes a sincere, internally guided faith and is considered the most tolerant form of religion. Extrinsic religiosity, on the other hand, is externally driven and influenced by societal expectations.

Putnam and Campbell (

2012) assert that religious beliefs and values promote religious tolerance, encompassing attitudes and behaviours that respect others’ rights to uphold their religious beliefs and practices without restrictions (

Hook et al. 2017). However, it is important to note that each credo does not solely determine religious tolerance, as other individual socioeconomic characteristics also play a significant role. Studies have shown that attitudes towards religions differ between the young and the elderly (

Kubicek et al. 2009;

Oliveira and Menezes 2018). Additionally, education and income levels influence religious tolerance, with higher levels of education and medium/high economic statuses being associated with greater tolerance towards religious out-groups (

Ferrara 2012;

Rees 2009).

The philosophical implications of religious tolerance constitute another area of study that addresses theoretical and conceptual issues related to religious tolerance in political philosophy.

Parekh (

1990) and

Wielandt (

1993) proposed a research program to explore the broader philosophical implications of religious tolerance in pluralistic societies with Muslim populations. Their work invites a critical reflection on the nature of tolerance and its implications for the peaceful coexistence of different faiths and cultural traditions. Moreover, scholars have analysed how Muslims integrate into diverse societies and multicultural contexts.

Gerholm et al. (

1994) highlight the role of Islam in promoting balance and tolerance in multicultural settings, emphasising the religion’s values of peace, justice, and mutual respect.

Studies also emphasise distinguishing between religion and religious fundamentalism in fostering tolerance towards out-groups.

Carnes and Karpathakis (

2001) introduce the issue of secularization, suggesting that religions shaped by tolerance and secularization may inadvertently lead to religious–ethnic conflicts.

Hostility towards other religious groups can also stem from resistance to secular humanism, as discussed by

Wallerstein (

2005) and

Fekete (

2006). These studies highlight how certain sectors of society may perceive secular humanism as a threat to their religious and cultural traditions, leading to hostility, as also addressed in the studies of

Beaman (

2003),

Savage (

2004),

Kaczyñski (

1999), and

Alietti and Padovan (

2013). These studies underscore how Muslims face intolerance in various aspects of social life, such as employment, education, and access to services. Cultural biases, negative stereotypes, and irrational fears fuel intolerance and discrimination.

Intolerance and negative stereotypes associated with Muslims are significant objects of study and reflection. Several scholars have examined this phenomenon, contributing to understanding the social, cultural, and political dynamics that influence these perceptions. Studies highlight how Muslim immigration is often subjected to negative stereotypes and prejudices in host societies. Muslims may be perceived as a threat to culture, national identity, and security. Cultural, religious, and linguistic differences can reinforce the notion of incompatibility between Western and Muslim cultures. Furthermore, the media and political discourse play a significant role in constructing stereotypes and threats related to Muslim immigration, often presenting a distorted or biased narrative about Muslim immigrants while disregarding their positive contributions (

Alietti and Padovan 2013;

Erk 2011;

Henkel 2008;

Karlsson 2007;

Knippenberg 2006;

Tardif 2011;

Vasta 2007).

3. Data

The dataset used in this study was extracted from the WZB—Berlin Social Science Centre dataset, specifically from the module on Religious Fundamentalism and Radicalisation Survey. The survey is conducted across multiple countries, including Cyprus, Germany, Israel, Kenya, Lebanon, the Palestinian territories, Turkey, and the USA. Its objective, designed by

Kanol et al. (

2021), is to investigate religious radicalization among individuals practising Christianity, Judaism, Islam, and atheism. However, the survey goes beyond its primary focus and incorporates supplementary questions aimed at delving into various aspects of religion, such as the study of attitudes towards different religious groups.

Table 1 provides an overview of the sample, showing that the USA and Cyprus have the highest representation, while Palestine has the lowest. The survey predominantly encompasses younger participants, with the most prevalent age groups being those under 25 (23.64%) and individuals aged 26–35 (25.99%). Conversely, the smallest group comprises individuals over 75 years old, accounting for only 2.19% of the sample. Men and women are evenly represented, comprising approximately 50% of the respondents. A noteworthy proportion of interviewees possess a bachelor’s degree (20.33%) or have completed upper secondary education. Furthermore, almost all participants are converted to one of the religions examined in the survey (92.33%). Moreover, the interviewers themselves are predominantly Muslim (57.19%) or Christian (31.81%), with only a small percentage identifying as Jewish (11%).

In terms of income, most of the sample earns less than €3000 per month, and the most represented income group falls within the range of €500 to €1000 per month. Regarding attitudes towards religious teachings, over 53% of the respondents disagree that individuals who commit malpractice in the eyes of God or Allah should be killed. Regarding experiences with religious discrimination, many participants report never or rarely encountering such discrimination (38.90% and 31.68%, respectively). Additionally, most respondents demonstrate an acceptable level of religious knowledge.

The WZB dataset contains four items about opinions towards the three main monotheistic religions. Following the methodology employed by

Kanol et al. (

2021), these items gauge Attitudes Towards Religions (ATR) by eliciting respondents’ opinions regarding various groups. Respondents are requested to express their opinions on a scale of 0 to 100, where 0 indicates a highly unfavourable opinion, and 100 represents a highly favourable opinion towards Jews, Christians, Muslims, and Atheists (

Table 2).

4. Methodology

Composite indicators (CIs) play a crucial role in analysing multidimensional phenomena, commonly employed by researchers. In their study on CIs,

Mendola and Volo (

2017) introduced a comprehensive set of 15 criteria that researchers should carefully consider when developing such indicators. Among these criteria, two are particularly essential: criterion 11, which focuses on the weighting method for combining individual indicators, and criterion 12, which addresses the aggregation method. In the extensive literature on CIs, unweighted indicators are commonly represented by simple averages or other functional forms that employ equal weights.

This paper utilizes the Fuzzy-Hybrid TOPSIS method to assess Attitudes Towards Religions (ATR) using the data provided by WZB (

Kanol et al. 2021). The measurement of religious tolerance is based on a semantic scale of 11 points, corresponding to the transformation of the thermometer scale represented in

Table 3.

Social science constructs heavily rely on responses obtained through Likert or semantic ordinal scales, commonly used to capture vague information that cannot be easily quantified as crisp, equidistant numbers [43,44]. These scales involve presenting respondents with statements reflecting positive or negative connotations related to the phenomenon under study and asking them to evaluate these statements using a n-point scale. The complexity of the mental processes involved in responding to such questionnaires leads to the recognition that the provided information is often uncertain or vague. In order to capture and represent this vagueness, fuzzy sets are utilized as proxies for the information gathered (

Bellman and Zadeh 1970;

Martín and Indelicato 2023;

Zadeh 1965;

Zadeh 1975;

Zimmermann 2011).

Fuzzy Set Theory (FST) provides a suitable framework for accommodating the imprecise nature of information obtained from ordinal semantic scales and has found widespread applications in various disciplines. In the field of Multiple Criteria Decision Making (MCDM), fuzzy sets have been successfully applied to address empirical applications in various topics (

Martín and Indelicato 2022;

Mohsin et al. 2019). The use of FST in MCDM is becoming precious as it allows for the analysis of scales from a multivariate perspective, where there is often no unique objective function to measure latent concepts commonly found in social science (

Martín et al. 2020).

Fuzzy sets introduce vagueness through membership functions that serve as proxies for the relative truth present in the statements (see Equation (1)). These membership functions allow for the precise and rigorous study of vague conceptual phenomena within a strict mathematical framework provided by FST (

Zadeh 1965;

Zimmermann 2011).

In our study, we employ Triangular Fuzzy Numbers (TFNs) as the fuzzy sets to manage the information matrix of responses on opinions towards religions (

Table 4). TFNs are commonly used by researchers dealing with uncertainty and vague information. They are characterized by a triplet representation, where the interval extremes represent thresholds determining possible values, and the midpoint represents the most likely value.

To analyse the TFN (Triangular Fuzzy Number) information matrix, the aggregation of TFNs and calculation of average TFNs for each population segment of interest is carried out using Fuzzy Set Logic Algebra, as follows:

This process results in a matrix of TFNs known as the TFN information matrix. However, analysing this matrix in its original form can be challenging. Hence, a defuzzification process is applied to synthesise the information, deriving a crisp value information matrix ().

One widely used defuzzification method for this purpose is

Chen’s (

2008) defuzzification method, which involves taking the weighted average of the TFN triplet. According to this method, the crisp value

can be calculated as

where

,

, and

represent the lower, middle, and upper values of the TFN triplet, respectively. This defuzzification method serves as a robust tool for transitioning from fuzzy to crisp values within the context of Triangular Fuzzy Numbers (TFNs). As aforementioned (

Chen 2008), this method’s application allows for the derivation of a concise and interpretable representation from inherently vague and uncertain data.

Once the defuzzified crisp information matrix () is obtained, the Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solutions (TOPSIS) analysis is applied. This analysis involves calculating the Positive Ideal Solution (PIS) and the Negative Ideal Solution (NIS). The PIS is determined based on the maximum values observed across all groups and items, while the NIS is determined based on the minimum values.

To calculate the PIS and NIS, the following formulas are used:

where

j are the items included in the scale and

i refers to the groups.

After obtaining the PIS and NIS, Euclidean distances are calculated between each observation (population group) and the ideal solutions. The Euclidean distance between an observation and the PIS (

) is calculated as the square root of the sum of squared differences between the observation’s crisp values and the corresponding PIS values (

). Similarly, the Euclidean distance between an observation and the NIS (

) is calculated as the square root of the sum of squared differences between the observation’s crisp values and the corresponding NIS values (

). Mathematically

and

are calculated as follows:

The Euclidean distances are then used as a basis for comparing relative distances between the observation and these ideal solutions. The Attitudes Towards Religions (ATR) index is then calculated as the ratio of

(distance from the NIS) to the sum of

(distance from the PIS) and

(distance from the NIS). The formula for calculating the RT is:

The ATR is a relative index, with higher values indicating that a segment is closer to the positive ideal solution and farther from the negative ideal solution. By ranking the observations in descending order based on the ATR values, it is possible to determine the strength of attitudes towards religions for each group of interest to the researchers. A higher ATR value stands for a higher religious tolerance, while a lower value is associated with religious intolerance. This ranking allows for a comparative analysis of the groups. The details regarding this methodology can be found in the references (

Cantillo et al. 2020;

Martín and Indelicato 2022).

5. Results

5.1. Attitudes towards Christianity, Islam, and Judaism

This paper utilises the Fuzzy-Hybrid TOPSIS approach to evaluate Attitudes Towards Religion (ATR) using data obtained from WZB (

Kanol et al. 2021). The ATR measurement is based on a thermometer scale ranging from 0 (not favourable) to 100 (very favourable). Two variations of the TOPSIS approach are applied: (a) calculating a TOPSIS indicator by groups; and (b) applying TOPSIS at an individual level. Additionally, the thermometer scale is transformed into an 11-point semantic scale.

Table 5 presents the results of Fuzzy-Hybrid TOPSIS for each group of analysis by using Equation (8). Germans, Israelis, and Turks show higher levels of ATR, while individuals from Cyprus, Lebanon, and Palestine demonstrate lower openness towards religions. With regards to the age variable, older individuals tend to have more favourable opinions towards religion, whereas those under 35 have the lowest levels. Religious affiliation appears to influence ATR, with Jews displaying a higher indicator (0.68) than Christians (0.52) and Muslims (0.38). Notably, this study finds that religious conversion or non-conversion does not significantly impact on opinions towards religions, showing ATR indices of 0.45 and 0.48, respectively.

Regarding the respondents’ main status, the results indicate that pensioners, individuals with disabilities, and those on parental leave show better attitudes towards religions than housewives and housemen, the unemployed, or students. Moreover, higher-educated individuals and those with higher incomes display greater ATR than their lower-educated and lower-income counterparts.

The questionnaire includes a question about attitudes toward individuals who commit evil in the eyes of God, and those who agree or strongly agree (indicating a more fundamentalist perspective) have favourable opinions towards religion (0.33) compared to those who disagree (0.57). Regarding experiences of religious discrimination, the results are somewhat contradictory. Individuals who frequently or rarely experience discrimination based on religion tend to be more open than those who have never or always experience religious discrimination.

The Fuzzy-TOPSIS indicator is also valuable for assessing ATR among Christians, Muslims, and Jews towards out-group religious communities (

Table 6). The results show noteworthy patterns in ATR levels across these groups. Jews are more open towards other religious groups, while Muslims demonstrate the lowest level of ATR. Christians display higher levels of attitudes towards other-religious groups when excluding Muslims from the analysis, but their ATR values decrease when Christians themselves are not part of the out-group.

Additionally, the results suggest that Jews are initially less open towards out-group members but become more favourable when Muslims are excluded. Thus, religious affiliation significantly influences ATR, with Jews exhibiting the highest level of tolerance, followed by Christians, and then Muslims. These findings hint at the possibility that certain religious beliefs or cultural factors may contribute to the comparatively lower level of ATR among Muslims towards other religions.

However, it is essential to acknowledge that these findings may not universally apply to all individuals and contexts, as various other factors, including personal experiences, social norms, and political and economic circumstances, can influence ATR. Therefore, understanding the dynamics of ATR between different religious groups is crucial. While an examination of attitudes towards the major monotheistic religions has been conducted, it is crucial to underscore that each of these encompasses very diverse internal groups in terms of interpretations, rituals, and convictions. This knowledge can empower policymakers and religious leaders to develop effective strategies and interventions that foster religious tolerance and diminish religious conflicts.

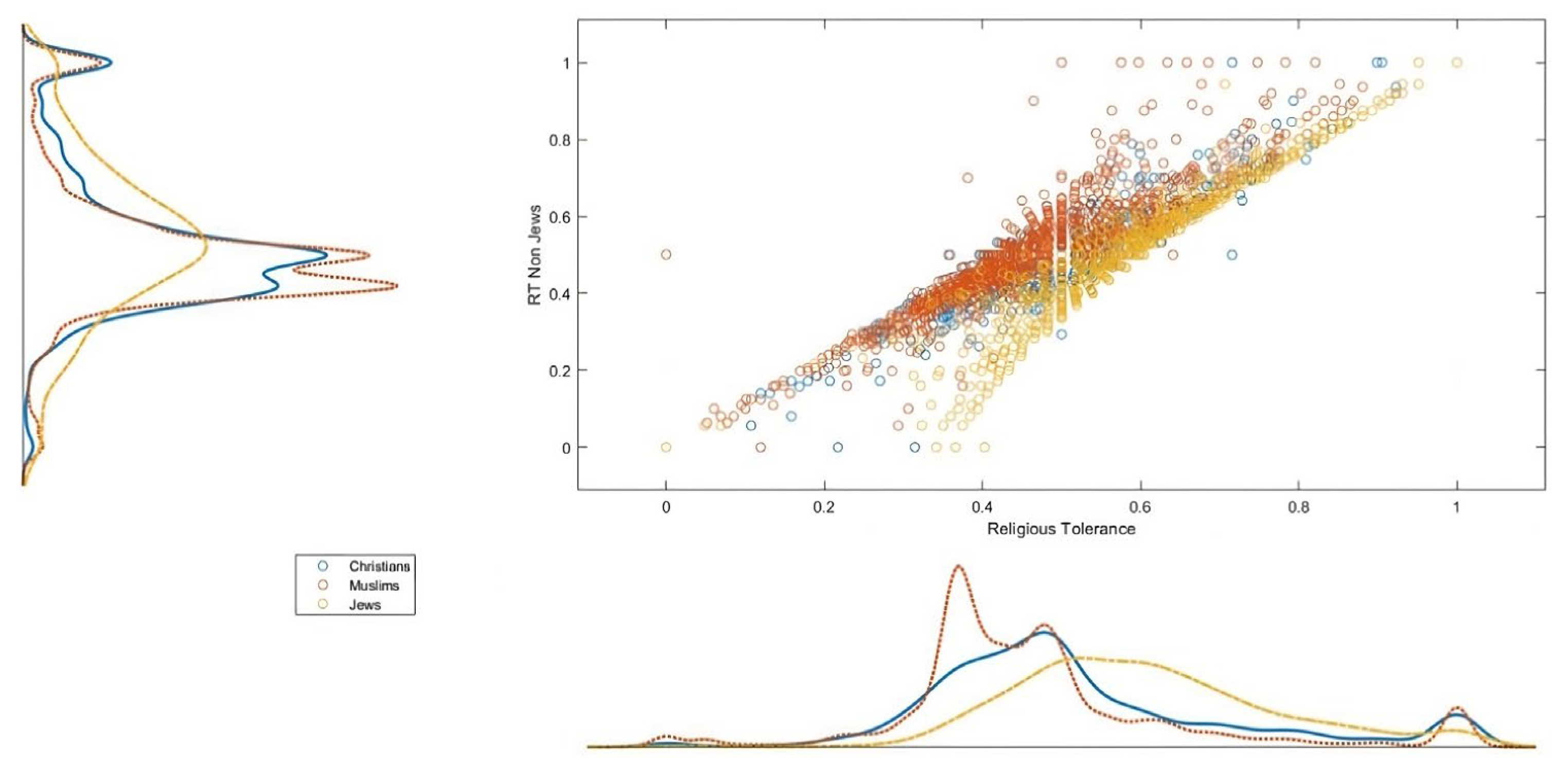

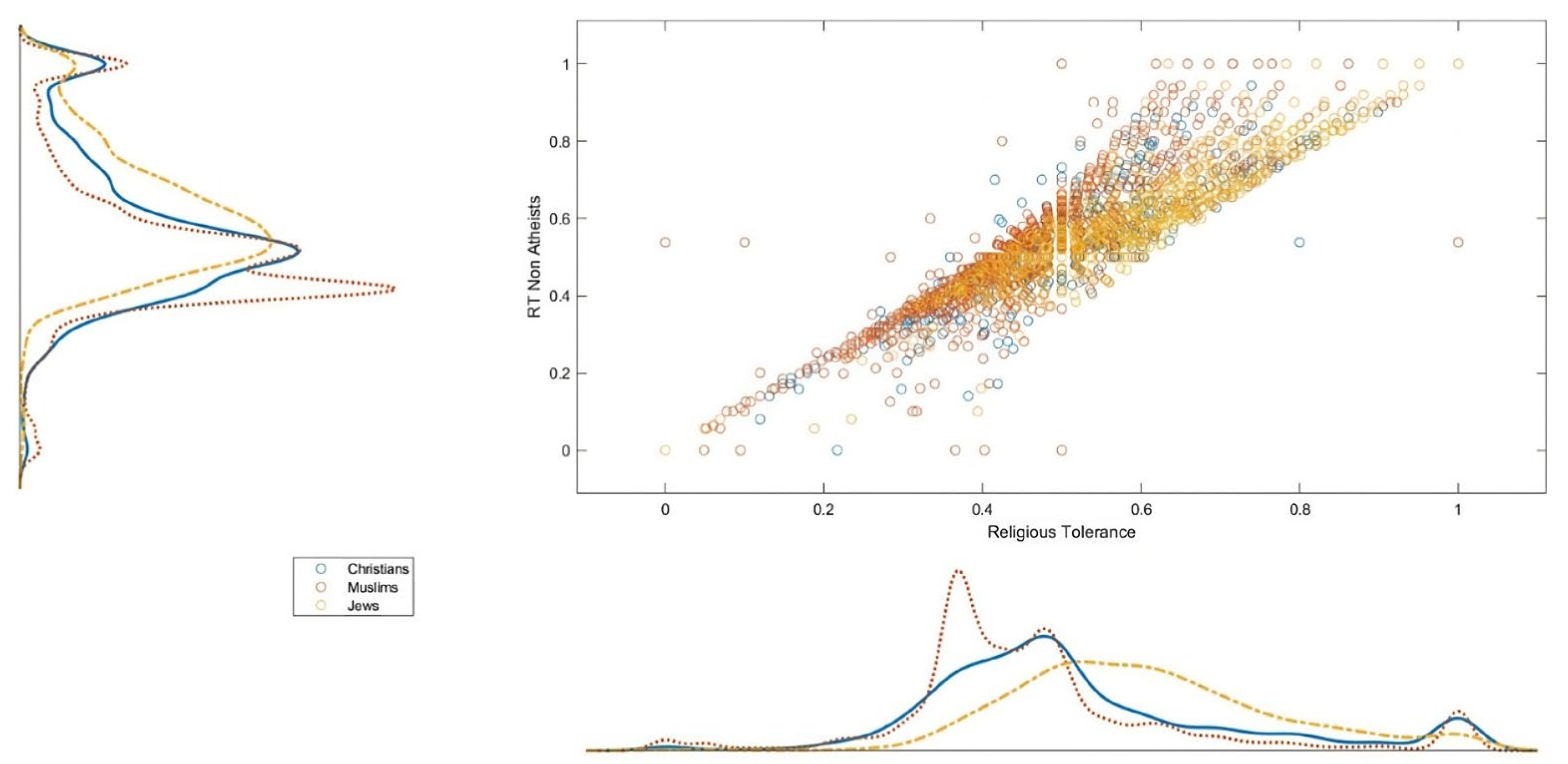

5.2. Attitudes towards out of the Religious Group

This section thoroughly analyses attitudes towards religions among Christians, Jews, and Muslims, specifically focusing on their attitudes towards out-group religions. The main objective is to examine the fluctuations in this sentiment across different religious groups, employing Equation (8) at the individual level. We investigate how attitudes towards religions of Jews, Christians, and Muslims are impacted when they are included or excluded from the analysis. We effectively utilise density graphs to present these insights (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Figure 1 highlights the changing perceptions of adherents of the Bible (Old and New Testaments) and the Koran for individuals of different faiths, except for Jews. The density distributions of these three monotheistic religions are predominantly concentrated around the centre, although there are some deviations. It should be noted, however, that in the lower tolerance range, the number of Christians is smaller, while Muslims and Jews are relatively more present. As suggested in

Jikeli (

2023), the individuals with the less open attitiude towards Muslims and Christians are the Jews. Conversely, the followers of Christ have better attitudes towards other religious groups.

The analysis of attitudes towards non-Christians provides interesting insights into the attitudes of different religious groups (

Figure 2). First, the results show that Jews tend to be more open to non-Christians, as they are mainly concentrated on the higher ATR values. On the other hand, Christians have a different tendency in ATR distribution. They are predominantly found in the lower ATR values, indicating less favourable opinions towards non-Christians. That is, followers of Christ show a greater degree of reservation or scepticism when embracing individuals of other religious backgrounds. On the other hand, Muslims show a wider diffusion in a concentration in the central band, indicating a moderate level of attitudes towards non-Christians within the Muslim community. Following the study of

Cohen (

2022), our results show that there is also a significant presence of Muslims with higher ATR values. This subgroup of Muslims shows great acceptance of non-Christians.

The analysis of attitudes towards non-Muslims also provides valuable insights into the attitudes of different religious groups (

Figure 3). First, Jews show a homogenous distribution of the highest ATR values, suggesting consistent and relatively better attitudes towards individuals of Jews and Christians. On the other hand, Christians show a different trend in the distribution of ATRs, mainly focusing on a moderate level of acceptance towards Christians and Jews. However, there is an interesting spike in the highest values of ATR, suggesting the presence of a subset within the Christian community, which exhibits a high level of openness when excluding Muslims from the analysis. Regarding Muslims, however, their ATR distribution is distributed towards the lower values, indicating a lower level of attitudes towards individuals belonging to other religious groups. The analysis reveals distinct patterns of religious attitudes towards non-Muslims. Despite historical and geopolitical divergences, such as the Israeli–Palestinian conflict (

Kronish 2022), Jews show a consistently high ATR level, Christians a moderate level with a subgroup showing better acceptance. In contrast, Muslims show a lower level of ATR.

The analysis of attitudes towards non-atheist groups sheds light on the tendencies common to monotheistic religions. Across all these religious groups, most followers show a higher density in the middle of ATR values, indicating a moderate level. However, it is important to recognize the exceptions within this general pattern.

According to

Alabdulhadi (

2019), Muslims focus on the lower ATR values, suggesting the worst attitude towards those who profess Christianity, Judaism, and other Muslims. However, there is also a notable presence of Muslims at the high end of ATR values. Therefore, there is a group of believers of the Koran which shows a higher acceptance towards non-atheists. Jews, on the other hand, are mainly concentrated in the half that includes the highest ATR values, implying that Jews, as a religious group, exhibit a relatively higher openness towards others, provided they are not atheists.

The analysis thus reveals that monotheistic religions share common tendencies in attitudes towards other-religious groups. Most followers of the analysed religions tend to show a moderate level of openness, clustering around the middle range of ATR values. However, there are variations between different religious groups. Muslims present lower ATR values, but a subset of the community shows a higher acceptance level. Jews, on the other hand, show a relatively higher level of openness, predominantly distributed in the higher values of ATR. These findings support other studies that underscore the intricate nature of religious interrelations and the importance of recognising and understanding different perspectives within and between different religious communities (

Alabdulhadi 2019;

Cohen 2022;

Jikeli 2023;

Kronish 2022).

6. Discussions

The present study provides significant insights that deepen the understanding of the complex nature of attitudes towards religions and their variations across different faith groups. The analysis of religious attitudes towards groups outside their respective religions has revealed distinct patterns and differences between Jews, Christians, and Muslims.

Jews consistently demonstrate the highest favourable opinions towards other religious groups, irrespective of the specific group being considered. Their values pertaining to religious acceptance predominantly align with the higher end of the spectrum, reflecting a robust endorsement of openness and inclusivity towards individuals of varying faiths. These findings align with previous research emphasizing the historical emphasis on the religious attitudes within Jewish traditions and the importance of coexistence among diverse communities (

Alabdulhadi 2019;

Cohen 2022;

Jikeli 2023;

Kronish 2022;

Mowlana 1994).

On the other hand, Christians exhibit a more nuanced pattern of attitudes towards religions. When non-Christians are considered an out-group, Christians display a moderate religious attitude level with some variations. However, if Muslims are excluded from the analysis, a subset of Christians shows a more favourable opinion towards the out-group, suggesting that within the Christian community, individuals are more accepting and inclusive of people from religious backgrounds other than Islam. These findings underscore the diversity of attitudes within the Christian population and the potential to promote greater community tolerance (

Alabdulhadi 2019;

Cohen 2022;

Jikeli 2023;

Kronish 2022).

Muslims generally exhibit more hostility towards other religious groups, including Christians, Jews, and atheists, than followers of the Abrahamic and Christian traditions. The values of the indicator that measure the attitudes towards religions among Koran followers tend to cluster in the lower range, indicating a relatively lower degree of acceptance and openness towards individuals of different faiths. As in

Dowd (

2016), it is important to note that within the Muslim community, a subset demonstrates more favourable opinions towards non-Muslims, highlighting the need to acknowledge the diversity of perspectives within the Muslim population and promote greater tolerance and mutual understanding. This could be attributed to the fact that the paper examines countries such as Lebanon, where a political and cultural power dynamic is established through the coexistence of Muslims and Christians (

Serhan 2019).

These results emphasise the influence of religious affiliation on attitudes towards religions, with Jews exhibiting the highest level, followed by Christians and then Muslims. However, it is crucial to recognise that religious attitudes are complex phenomena influenced by various individual, social, and cultural factors besides religious beliefs and teachings (

Ozorak 1989). Thus, this study shows that age, education, income, and personal experiences can also impact opinions towards religions (

Alabdulhadi 2019;

Cohen 2022;

Ferrara 2012;

Jikeli 2023;

Kronish 2022;

Rees 2009).

Analysing opinions towards religions at the individual level provides further insights into variations within religious groups. Christians and Muslims demonstrate a wider range of values for attitudes towards religions, highlighting the diversity of attitudes and perspectives within these communities. Variations exist among subgroups within religious denominations, such as Christians, when it comes to their attitudes toward other belief systems, stemming from their distinctive doctrines, theological interpretations, and historical contexts. For instance, consider the Roman Catholic Church, which has actively endorsed inter-religious dialogue and tolerance, particularly in the wake of the Second Vatican Council (

Morales 2001). In the Protestant faith, a general emphasis on religious freedom prevails (

Littell 1963), although certain conservative factions might exhibit diminished tolerance, particularly towards differing faiths. In the same context, the Christian Orthodox may exhibit a lower open attitude towards other religious groups and a more attachment to the traditions and culture of one’s faith (

Ben-Nun Bloom and Arikan 2012). This variation underscores the importance of avoiding generalizations and recognizing individual differences within religious communities. It also suggests that efforts to promote religious tolerance should consider the diversity of attitudes within each religious group and tailor interventions accordingly.

The findings of this study have significant implications for politicians, religious leaders, and society. Recognising the variations in attitudes towards religions within and between different religious groups can inform the development of targeted interventions and initiatives to foster greater understanding, respect, and cooperation among diverse religious communities. Efforts to facilitate interreligious dialogue, promote cultural exchange, and challenge negative stereotypes and prejudices are essential for building more inclusive and tolerant societies.

7. Conclusions

This article explores the attitudes towards external religious groups. It utilises data extracted from the WZB dataset provided by

Kanol et al. (

2021), focusing on opinions towards religion measured through four items. The Fuzzy-Hybrid TOPSIS approach is applied to provide a synthetic indicator that measures citizens’ attitudes towards religions. The methodology combines the Fuzzy Set Theory and MCDM TOPSIS analysis to capture the imprecise and vague nature of information obtained from semantic scales.

The results demonstrate the dynamic nature of opinions towards religions among different religious groups. Jews exhibit the most favourable attitudes towards other religious groups, followed by Christians. Conversely, Muslims display the lowest level of religious acceptance. Additionally, the results indicate that socioeconomic factors can shape citizens’ opinions towards religions. Age, education, income levels, and experiences of religious discrimination also influence these attitudes.

This study contributes to the scientific discourse on attitudes towards religions through the utilization of a deterministic approach alongside innovative quantitative methods. This methodology not only provides a means to encapsulate opinions towards religions within different groups through a synthesized indicator but also facilitates a comprehensive analysis of the interplay among monotheistic religions in terms of mutual acceptance.

However, despite the methodological innovations proposed in this work, it is important to highlight some limitations. Even if the attitudes towards the three major monotheistic religions—Christianity, Islam, and Judaism—have been explored, it must be highlighted that each of these encompasses a diverse spectrum of beliefs, practices, and cultural nuances. Notably, even within a singular religious community, significant variations in interpretations, rituals, and convictions can be observed. The aim of upcoming research stands on overcoming a central obstacle that lies in acknowledging the remarkable diversity of beliefs and practices existing within these religious groups. By doing so, we aspire to enhance our comprehension of the research findings, fostering a more comprehensive understanding.

Then, as the database used here is limited to analysing only eight countries, it would be interesting to explore other databases that provide a broader geographical perspective. Furthermore, this study exclusively explores the attitudes of Christians, Jews, and Muslims, excluding other religions such as Buddhism or atheism. Expanding these boundaries and analysing a broader religious context is our next aim. Finally, while this study examines attitudes towards other religions, it would be interesting to study the opinions of religious individuals towards other minority groups, such as immigrants and the LGBTQI+ community.