1. Introduction

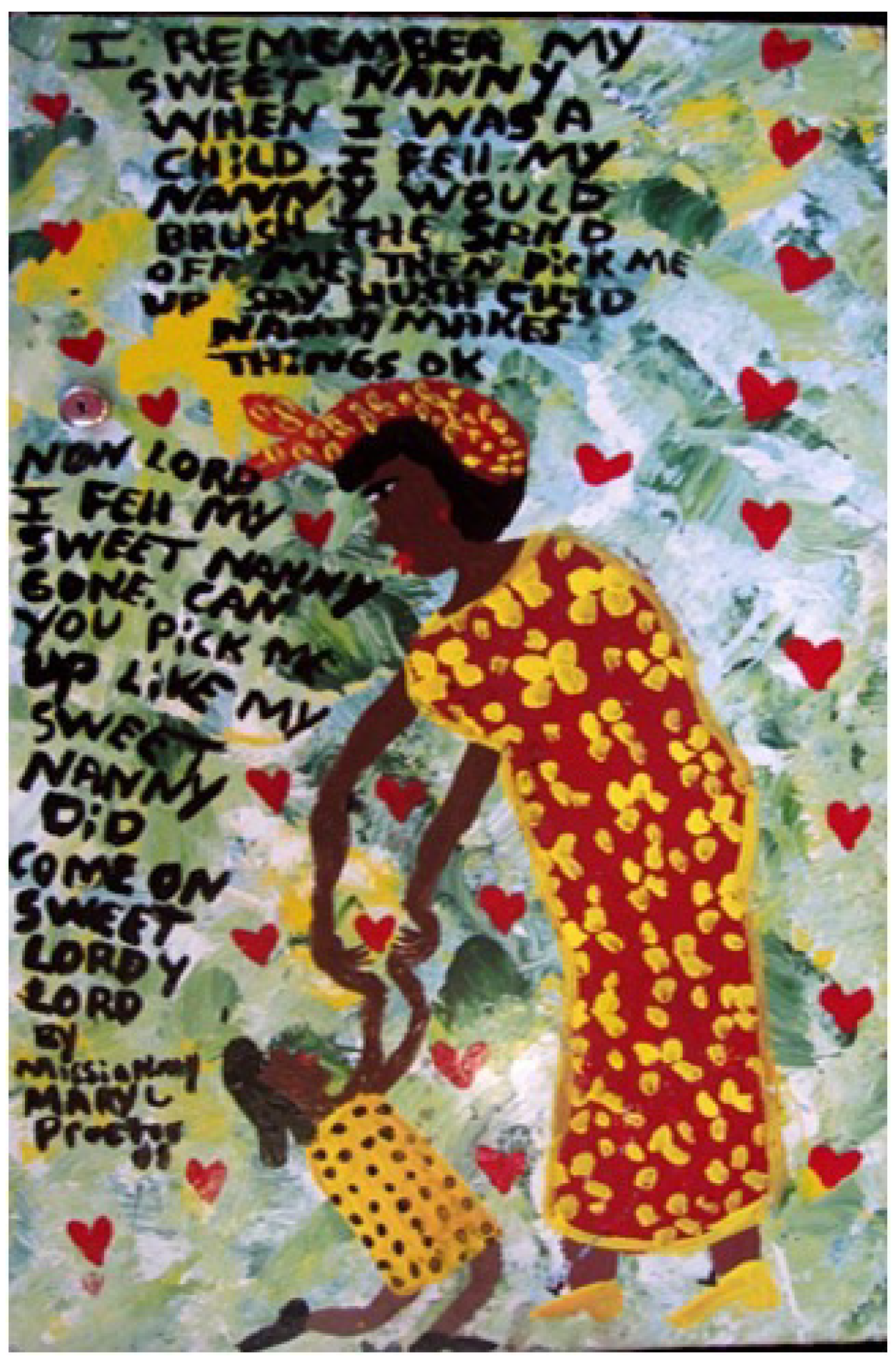

I remember my sweet Nanny when I was a child. I fell, my Nanny would brush the sand off me, then pick me up say hush child, Nanny makes things okay. Now Lord I fell, my sweet Nanny gone, can you pick me up like my sweet Nanny did? Come on sweet Lordy Lord.

Freedom—personal and political—is an enduring motif of African American aesthetics and faith-based practices. Zora Neale Hurston’s anthropological research brought critical awareness to the manner in which rural, Southern African American communities steadfastly sought freedom and resisted oppression through cultural creation and spiritual uplift.

In this paper, I examine the enduring legacy of Zora Neale Hurston, whose pivotal role in legitimizing the cultural, spiritual, and philosophical richness of African American folk culture opened the door for generations of artists, scholars, and writers dedicated to exploring Black religious and cultural experience.

I situate my analysis of contemporary folk artist Missionary Mary Proctor and the spiritual roots of Southern African American aesthetics within the context of Hurston’s novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, and her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road. In Missionary Mary Proctor’s art, the dynamic relationship between God and his Black female worshippers reveals as much about the faithful as it does about their concept of the divine. Similar to Hurston, Missionary Mary Proctor validates ideals of freedom and transcendence deeply immersed in African American experience, especially in the faith-based aesthetics of African American women. In so doing, she emulates Hurston in achieving a womanist aesthetic that celebrates Black women as bold, audacious, and determined to embrace their lived experiences as the foundation of their faith.

2. Eyes on the Prize

In

Their Eyes Were Watching God, Nanny issues a wry statement to Janie that black women are the “de mule uh de world” (

Hurston 1937). Through this statement, Nanny conveys her view of the legacy of African American women in which subjugation and oppression are the prevailing themes. Her statement bears a cynical wisdom, one reached after years during which she and other Black women toiled like mules for little reward. The pragmatic goal of security took precedence in Nanny’s life, and she sought to impose this worldview upon Janie in an effort to shield her from undue hardship.

Janie, however, is a product of a different sensibility. Janie is a young Black woman who craves a personal, spiritual encounter with freedom—one that transcends the rigid life choices that have circumscribed Nanny’s existence. While Nanny provides a historical trajectory among Black women in the narrative, it is Janie who must plot a new roadmap, redefining freedom, fulfillment, and love as a Black woman.

Black women such as the fictional Janie do not see themselves as trapped, they are in the process of planning a new existence. They hope for a better day, for “a change that’s gonna come”, and maintain faith in God’s ability to uplift them, in addition to their abilities to change circumstances through sheer will and determination. If indeed their eyes are watching God, they believe that He too is watching and preparing them for a more empowered present and future. It is a careful, demanding watchfulness, one that echoes the intensity of the Gullah spiritual “Lord, I dun dun what you told me to do”. My part of the bargain has been fulfilled. I seek your deliverance.

For African American women, faith in tomorrow is not abstract. It is palpable and tangible. It is a faith conveyed through bodily movement and exhibited in artistic enterprise. Janie listens to Nanny, but she still sets out on her own, determined to claim joy as her birthright. She bravely sets out unencumbered by what others may perceive as the limitations of her race and gender. She boldly seeks love and leaves situations where it is not to be found. And at the end of the novel, after her many trials and tribulations, Janie finds peace:

She pulled in her horizon like a great fish-net. Pulled it from around the waist of the world and draped it over her shoulder. So much of life in its meshes! She called in her soul to come and see.

Katie Cannon (

1985) coined the term “womanist ethics” to denote the theology and spiritual praxis of Black women. She attributes this theology to a tradition of “Black women buttress[ing] themselves against the dominant coercive apparatuses of society. Using a series of resistance modes, they weave together many disparate strands of survival skills, styles, and traditions in order to create a new synthesis which, in turn, serves as a catalyst for deepening the wisdom source which is genuinely their own” (

Cannon 1987, p. 170).

In her landmark text on the subject, Cannon draws attention to Zora Neale Hurston as a pivotal figure within the womanist ethical tradition:

Zora Neale Hurston and her fictional counterparts are resources for a constructive ethic for Black women, wherein they serve as strong, resilient images, embodying the choices of possible options for action open within the Black folk culture. As moral agents struggling to avoid the devastating effects of structural oppression, these Black women create various coping mechanisms that free them from imposed norms and expectations … As the bodily, physical, and psychical representatives of the majority of the members of the Afro-American female population, Hurston and her characters serve as the consciousness that calls Black women forth so they can break away from the oppressive ideologies and belief systems that presume to define their reality.

While Hurston did not engage directly or exclusively with faith in many of her writings, Cannon argues that “the religious heritage that is central to the Black community is latent throughout her work” (

Cannon 1988, p. 15). Hurston’s writings and her own life create a template for understanding faith, values, and beliefs within the lives of African American women. It is important to recognize that Hurston gives space to both Nanny and Janie in

Their Eyes Were Watching God. Nanny’s wariness and Janie’s determination are equal components of African American women’s spiritual walk. As foremother, Nanny passes along the wisdom that her young granddaughter needs to survive. Hurston honors the tradition represented by Nanny while also giving voice to Janie, because the two characters jointly embody the trajectory of faith for Black women—a spiritual lineage inherited from grandmothers and mothers. As

Cheryl Townsend Gilkes (

2011) notes, “if we take seriously the power of mothers … then we may need to reimagine the entire span of African American religious history with women at the center”.

Janie imbibes Nanny’s wisdom and sets forth on her own path of discovery as a Black woman. Throughout her adventures and misadventures, she plots her destiny, keeping her “eyes on the prize”, in the words of the African American folk song:

Got my hand on the freedom plow

Wouldn’t take nothing for my journey now

Keep your eyes on the prize, hold on

Janie forges her independence within a trajectory of Black womanist faith— a pattern well understood by Hurston due to her life’s experiences. This pattern becomes the template for creation embraced by Hurston and her spiritual daughters in the vein of a womanist ethical praxis through art.

3. Harp and Sword

I have been in Sorrow’s kitchen and licked out all the pots. Then I have stood on the peaky mountain wrapped in rainbows, with a harp and a sword in my hands.

—Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston’s personal history reflected the dynamics present in the life of Janie in

Their Eyes Were Watching God. Hurston experienced both deep love and enduring trauma during her formative years. In her autobiography,

Dust Tracks on a Road, Hurston conveys the love and support and she experienced from her mother Lucy who “exhorted her children at every opportunity to ‘jump at de sun’. We might not land on the sun, but at least we would get off the ground” (

Hurston 1942). Zora’s headstrong, feisty temperament was embraced by her mother, who saw it as a sign of strength and encouraged her young daughter and “didn’t want to ‘squinch my spirit’ too much for fear that I would turn out to be a mealy-mouthed rag doll by the time I got grown” (

Hurston 1942).

Lucy Hurston understood that her baby girl would need her strong spirit to survive in the world as a Black woman and make something of her intellect and creative gifts. As a child, Zora hungered for stories, which abounded within the rich folklore of the African American community of Eatonville, Florida where she grew up. She was given to prophetic visions and her imagination was her best friend. As Valerie Boyd notes, “to many of Eatonville’s children, this proliferation of stories—or “lies”, as some folks called them—might have seemed ordinary, or even tiring. But these tales of God, the Devil, the animals, and the elements fueled Zora’s own inventiveness (

Boyd 2004).

Thus, from a tender age, the seeds of Hurston’s artistry were planted in the spiritually rich soil of her hometown. Lucy was wise to cultivate those seeds during her daughter’s childhood, for Zora’s adolescence was marked by trauma to which she might have succumbed were it not for the roots her mother had nurtured within her. When Zora was thirteen, Lucy died of a prolonged illness and Zora lost her biggest supporter. Lucy’s death was exacerbated by the tense relationship that Zora had with her father, which quickly worsened in her mother’s absence. After a violent altercation with her father’s new wife, Zora was forced out into the world, and began fending for herself while still a teenager. She endured many difficult times and often referred to her adolescence as “haunting years” without going into much detail (

Boyd 2004).

When Zora Neale Hurston reemerged years later at Morgan College in Baltimore, and subsequently at Howard University in Washington, D.C., she was a decade older than her classmates—a fact she hid. But whatever hardships transpired during those haunting years had not robbed her of her spirit. In the 1923 Howard yearbook, Hurston wrote, “I have a heart with room for every joy” (

Boyd 2004). She was still her mother’s child, seeking to jump at the sun and capture its radiance.

Throughout her life, Hurston remained invested in an idiosyncratic worldview that privileged her particular journey as a Southern-born African American woman. She moved through the world with a confidence that defied her material circumstances, for she understood herself to be rich in spirit. Reinvention and self-determination are motifs in Hurston’s life, career, and literature. Beyond the inspiration provided by her mother, Hurston drew strength from her anthropological studies of rural, Southern Black communities peopled with the mothers, grandmothers, and aunties similar to those from her own childhood (

Hurston 1935). In her seminal study, “Characteristics of Negro Expression”, she discusses, among other concepts, “originality” as a kind of re-interpretation and improvisation of existing ideas and concepts into something original and “the will to adorn”, or the creative interventions into spoken and written language by African Americans (

Hurston 1934).

“Characteristics of Negro Expression” is a text that lauds the aesthetics of Black Southerners—aesthetics largely shaped and embodied by Black Southern women. Hurston grew up around women who told long-winded stories that were embellished at each retelling. They were women who invented new words and new connotations for existing ones. And they were women who developed their own lexicon for speaking to, negotiating with, and interpreting the divine presence in their lives. Hurston rightly understood all of this as cultural praxis, even if it was largely ignored, maligned, or mocked as unworthy of serious consideration.

Cheryl Wall notes the difficulty through which Hurston and other Black women gained access to formal venues of cultural production. According to Wall, the problem was rooted in the folkloric treatment of Black women, which limited their visibility in literary and visual arts:

Although tales about women created by men, many of them virulently misogynistic, exist in some quantity, tales about women told from a female point of view are rare. In “Characteristics” Hurston had noted the “scornful attitude towards black women” expressed in Afro-American folk songs and tales.

Well-aware of the misogynoir of the culture, Hurston refused to let it limit her artistic trajectory. Throughout her career, she sought space in which to revel in the fullness of her existence as a Black woman, as she celebrated the humanity of her people. Hurston’s views on faith were expansive, and within her writings, discourses of faith function as one part of a much larger story about her people. Hurston paid close attention to the ways in which Black women utilize faith in seeking validation, respect, and freedom, and how this praxis informs the narratives and “characteristics” emerging from the culture, which includes her own aesthetics.

The image of Zora Neale Hurston on that mountain peak, wrapped in rainbows, bearing a harp and a sword in each hand, symbolizes the twin forces in the spiritual and creative journeys of African American women. The harp represents love, peace, light, beauty, and faith in transcendence. The sword represents struggle, righteous indignation, self-defense, and faith in survival. Both trajectories resound within Black women’s faith traditions and cultural production. Through her literary imagination, anthropological research, and lived example, Hurston created a roadmap for other Black women artists to follow in their faith-inspired journeys to freedom.

4. Missionary Mary

The spiritual quest for freedom through cultural praxis continues, reverberating in the folk art and faith practices of the rural Southern African American women of the twenty-first century. Missionary Mary Proctor is a self-taught Tallahassee-based folk artist who began painting in response to a divine intervention she experienced while grieving the loss of relatives who died in a house fire in 1995. Upon hearing the Lord command her to “paint the door”, Proctor did just that—painting dozens of doors and other objects with her signature motifs of rejoicing Black women alongside Biblical verses, proverbs, and personal reflections (

Proctor 2001b).

Missionary Mary Proctor’s womanist faith-based aesthetics are as essential to her art as they are to her life. There is a seamless integration between her subjective experience in the world and her rendering of that experience through art. As a collage artist working with found objects and discarded materials, she engages in a continuous restructuring of her world to suit her vision. Missionary Mary’s impetus to rescue, restore, and redeem is what led to her own self-redemption through art following the tragic death of her family members. Yet this aesthetic transcends the trauma of the artist’s personal experience, as it encompasses the collective ethos of the community she represents.

In Missionary Mary’s work, Black female figures embody a prideful yet humbled aesthetic. They are self-possessed and possessed by an intimate, activist faith. The women’s eyes are frequently cast upwards in hopefulness and anticipation. Missionary Mary’s collection is filled with positive and pained images of Black women. There is a preponderance of angelic imagery alongside images of the mundane, emphasizing the dichotomy between earthly struggle and heavenly aspiration. These women reflect the dynamics of the artist’s own journey, which she paradigmatically recreates in each of her works. The literary and visual elements of her art synchronically provide insight into the journeys that she and countless African American women have traveled.

The narratives inscribed on the collages are testaments to the experiences of Black mothers and grandmothers. In

A Broken Mother (see

Appendix A Figure A2), Missionary Mary chastises children who abuse and disrespect their wearied mothers, writing, “How can you break apart the best friend God lent you?” (

Proctor 1997). Just as Janie had respect for Nanny despite their differences, the message here is that Black youth owe a debt of gratitude to the women who sacrificed and labored on their behalf. Failure to pay that respect is deemed ungodly and ominous, insofar as Black children are bound to encounter the same struggles as their forebears, and a lack of empathy towards the older generation will only serve to further their confusion and alienation in the world.

Like Hurston’s Janie and countless others in the African American community, Mary Proctor was raised by her grandmother, who had a tremendous impact on her development. Missionary Mary’s grandmother is a central figure in her art, as anecdotes about their relationship anchor several collages. In

My Scrapdolls Story (see

Appendix A Figure A3), she writes:

When I was a child Grandma couldn’t buy me clothes. She would cut up old jeans, shirts, ties, etc to make me clothes for school. I was thankful they were made from the hands of love.

The collage is embellished with scraps of jeans and plaid shirts clothing the painted figures of a grandmother, granddaughter, and a cherished doll. The figures gaze lovingly at one another, hands clasped. The strength of their bond is what matters, as is the creativity and love that the grandmother put into clothing her granddaughter and her doll—embracing the aesthetics of originality and the “will to adorn” (

Hurston 1934). Just as Lucy Hurston was intent upon celebrating Zora’s unique spirit, Missionary Mary’s grandmother was determined to uplift and celebrate her granddaughter despite their material circumstances. The radical faith of these Black women in their girl children inspired women such as Zora Neale Hurston and Missionary Mary Proctor to boldly envision new worlds through their art.

Missionary Mary Proctor is attuned to the linguistic richness of Southern African American discourse, making ample use of it in her collages. In

My Grandma Penny Story (see

Appendix A Figure A4), she writes:

When I was a child I told my Grandma my good thoughts

She would say, “Good thoughts, child. But they ain’t worth a penny

Till you put them to good use and pennies make dollars

Proverbs and folk sayings are a hallmark of African American discourse; they frequently entail the colorful and creative use of language or what Zora Neale Hurston called “the will to adorn” (

Hurston 1934). In this narrative, Missionary Mary conveys the wisdom of her grandmother, artfully expressed through language. Grandma lovingly encouraged young Mary’s dreams while skillfully admonishing her to develop actionable plans to transform her thoughts into concrete objectives. Just as Lucy Hurston was careful not to crush young Zora’s spirit, Grandma wanted Mary to keep dreaming. But she also knew firsthand the struggles of survival as a Black woman, and she needed to encourage her granddaughter to develop the pragmatic skills that would enable her to surmount material obstacles en route to fulfilling her dreams.

In

My Grandma Old Plates (see

Appendix A Figure A5), Missionary Mary finds yet another opportunity to reflect on her grandmother’s ethos of love. In this collage, Mary depicts an older Black woman and a young girl, whose clothing and headscarves are fashioned from broken pieces of indigo-hued porcelain. The accompanying narrative reads:

I remember when I broke my grandma old plates

I thought she would whip me

instead she looked down and said “I forgive you”

cause just yesterday God forgave me and he said

one must forgive to be forgiven

Forgiveness is a value central to Christian theology and praxis. It is a feature of Black womanist ethics, though its manifestation reflects the complexity of Black women’s spiritual journeys across generations.

Zora Neale Hurston was attuned to the nuances of forgiveness as practiced within the cultural and religious milieus of Southern African American women such as Missionary Mary and her grandmother. In

Their Eyes Were Watching God, Nanny violently slaps Janie for refusing to acquiesce to her marriage plans for her granddaughter. She immediately regrets the act as “she brushed back the heavy hair from Janie’s face and stood there suffering and loving and weeping internally for both of them” (

Hurston 1937). Nanny then tries to contextualize her visceral response through a lengthy monologue on the hardships facing Black women, a speech that ends with her seeking Janie’s forgiveness for the mistakes she may have made while raising her:

Maybe it wasn’t much, but Ah done the best Ah kin by you …. Have some sympathy fuh me. Put me down easy, Janie, Ah’m a cracked plate.

MarKeva Hill writes of the complex interplay between womanist ethics and forgiveness, particularly as exhibited in relationships between Black women and their descendants. She notes an inherent tension in regards to “the [Black] mother’s request or conditioning that requires the daughter to ignore and/or accept her oppressive plight in order to survive in a racist, sexist, and classist society (

Hill 2012, p. 101).

Black girls have traditionally been raised to swallow their pain—and that of their mother figures—in order to achieve the goal of survival. This survival is occasioned by grace frequently bestowed upon them by the same individuals who command their fortitude. Mother figures such as Nanny and Missionary Mary’s grandma often make extraordinary efforts to love and nurture their daughters and granddaughters. However, they can never forget the danger that befalls Black girls for being too bold, too beautiful, too free. Price and fear, encouragement and admonishment, the loving embrace and the chastising rebuke are two sides of the same proverbial coin. The transgressions and contradictions of their behavior, however, are not nearly as remarkable as their repentance and ethos of forgiveness.

In

Trauma and Grace, Serene Jones ponders whether “grace might meet and heal an imaginative world disordered by violence” (

Jones 2019, p. 21). For Black women whose faith intersects with womanist ethics, the answer is an unequivocal yes. Such women embody grace as a lived practice. Nurturing one’s female progeny and attending to the brokenness in the matrilineal circle is one form of that grace. Both Nanny and Missionary Mary’s grandmother appear to recognize their own limitations as well as the deeply flawed societal context in which they are operating. In seeking forgiveness and in extending grace to others, they endeavor to rise above the limitations of their circumstances, creating pathways to dignity and transcendence for themselves and for their granddaughters.

Janie embraces the ethos of forgiveness many times throughout Hurston’s novel. She ultimately forgives Joe, her second husband, for his many abuses towards her, feeling pity for him upon his death bed. She forgives herself for killing Tea Cake, the love of her life, and comes to a place of peace. She does not, however, manage to forgive Nanny. At issue is Janie’s sentiment that, “Nanny had taken the biggest thing God ever made, the horizon—for no matter how far a person can go the horizon is still way beyond you—and pinched it in to such a little bit of a thing that she could tie it about her granddaughter’s neck tight enough to choke her” (

Hurston 1937).

Of all the relationships depicted in the novel, the matrilineal bond between Nanny and Janie is the most powerful. Black women pass along their deepest pain and most fervent prayer to their granddaughters and daughters, nurturing a bond unlike any other. Janie was hurt the most by Nanny because Nanny also gave her the most—she enabled her physical survival and watered the seeds of her spirit. While she could not give Janie freedom, she tried in her own way to save her from the entrapment of being a “mule of the earth” (

Hurston 1937). Had she lived longer, it is imaginable that the two women may have reconciled. In writing of the evolution of her relationship with her mother, Hill notes, “What moved my mother from matriarch to womanism, or from my enemy to my friend…was spiritual enlightenment that gave her an awareness of my pain (

Hill 2012, p. 103). Nanny is aware of Janie’s pain, though she is at a loss for how to deal with it effectively. She nonetheless prays for her granddaughter before she dies, imploring God to take care of her. Nanny modeled perseverance, repentance and self-forgiveness, and although Janie struggles to forgive her, she comes to embody those traits en route to freeing her spirit.

In the Hebrew Bible, the Israelites spent forty years wandering in the wilderness before reaching Canaan, the Promised Land. Zora Neale Hurston, her protagonist Janie, and Missionary Mary Proctor all endured wilderness seasons in their lives, what Hurston referred to as the “haunting years” of her turbulent adolescence following her mother’s death. Missionary Mary Proctor was traumatized in the aftermath of the 1995 house fire that killed her aunt, uncle, and her beloved grandmother. Janie was relegated to the wilderness after several disasters, most memorably following the killing of her beloved Tea Cake.

Delores Williams theorizes wilderness as a dichotomous landscape of womanist ethical praxis. It is at once a place of opportunity, connoting communion with God and freedom from mundane oppression, yet it is also a desolate realm of isolation and abandonment (

Williams 1993, p. 103). The notion that the wilderness is a site of escape and creative freedom seeking for Black women is not incidental, for despite the hardships it imposes, each of these women endured the wilderness and emerged as the architect of their destiny. The faith inherited from their foremothers led them to places where they could move forward with a dignity and strength belying their status as rural, working-class, Southern African American women. Like Zora Neale Hurston, Missionary Mary Proctor is a cataloguer of Black experience—particularly as it pertains to the so-called “mules of the earth” referenced by Nanny. In extending the tradition of creative inquiry and uplift pioneered by Hurston, Missionary Mary Proctor challenges the demeaning characterizations of Black women while forging her own path to liberation.

5. Faith on a Mission

For these grandmothers and mothers of ours were not Saints, but Artists; driven to a numb and bleeding madness by the springs of creativity in them for which there was no release.

—Alice Walker

In her essay, “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens” Alice Walker reflects on the wellspring of artistry emanating from Black women over the generations. She refers to these women—mothers and grandmothers—as Artists and Creators (

Walker 1983a). Zora Neale Hurston once remarked that, “Gods always look like the people who create them” (

Hurston 1938). The gods created by African American women Artists and Creators look like Missionary Mary Proctor’s grandmother, sound like Nanny, and dance like Janie danced when she fell in love with Tea Cake. These are gods intimately acquainted with joy and pain, gods who deeply understand their Creators because they are one and the same.

Alice Walker is credited with bringing Zora Neale Hurston back to the forefront of the public consciousness following decades of obscurity. In revitalizing interest in Hurston, Walker engaged in the broader project of validating the legacies of the Black women Creators upon whose shoulders she stands. Walker wrote:

Zora Neale Hurston, Billie Holliday, and Bessie Smith form a sort of unholy trinity … Zora belongs in the tradition of Black women singers … like Billie and Bessie, she followed her own road, believed in her own gods, pursued her own dreams.

The legacies of Black women Artists and Creators such as Zora Neale Hurston and Missionary Mary Proctor extend far beyond their art. These women embodied faith in themselves and in their destinies which enabled them to envision and actualize new possibilities for Black women in the world. Their artistry is a conduit to a deeper purpose and mission—that of liberating Black women by showcasing them as the divinely inspired and inspiring beings that they are.

The womanist aesthetic praxis of Hurston and Proctor is grounded in a faith tradition that is at once immediate and transcendent, pragmatic and ethereal. It entails creating art that embraces phenomenological possibilities, while triumphing over ontological realities. While the faith of Black women Artists and Creators represents a legacy passed from their foremothers—biological and spiritual—it is not a static tradition. It is a robust, activist praxis reflecting the traits of adaptability, endurance, and determination that enable the Creators to survive and to thrive.

Jumping at the sun is faithful, creative resistance to oppression. It is African American women surveying the landscape before them and declaring, as Janie does at the end of her sojourn, “Ah done been tuh de horizon and back and now Ah kin set heah in mah house and live by comparisons” (

Hurston 1937). It is the determined embodiment of belief in oneself and in a destiny glimpsed only in the Artist’s imagination. It is faith with wings like those depicted on the angelic figures in Missionary Mary’s art. “Just like a butterfly I can fly till I reach the sky” reads the inscription on one collage (

Proctor 1999) (see

Appendix A Figure A6). Faith and freedom are not a given; they are hard-won fruits of labor. For African American women Artists and Creators, faith is creativity in action; it is a determined aesthetic that paves the way to their liberation.