One of the changing elements is that the successive generations involved in the school will each tell a different story about the institution over time. After their establishment, schools undergo a development process that cannot be predicted in advance.

Edlin (

2010) distinguishes three phases or stages in the development of Christian schools. In the

aspirational stage, the school is in its initial phase. Some schools put a lot of work into the biblical foundation of their intentions. In the

dynamic stage, the school becomes known, and the organization is consolidated. In the

gentrified stage, the school reaches a state in which the original intentions are less recognizable. A new generation considers the school’s existence important but no longer keeps the founders’ inspiration in mind. The school’s operations are more or less managed smoothly, and there is no need to be constantly preoccupied with ideals. For the schools that initially turned against the mainstream culture with their faith-based programs,

Edlin (

2010, p. 100) recognizes the danger of dilution, referring to “schools which may retain a Christian linkage in their name but which operationally demonstrate few of the biblically authentic goals that motivated their founders”. In this article, however, we claim that the sequence of the three stages is not an ever-valid and inescapable fate. In any stage, schools have the opportunity to rediscover their aspirations. To avoid the loss of the schools’ Christian identity, it is wise—quoting Pazmiño again—“to reconsider the foundational questions” from time to time (

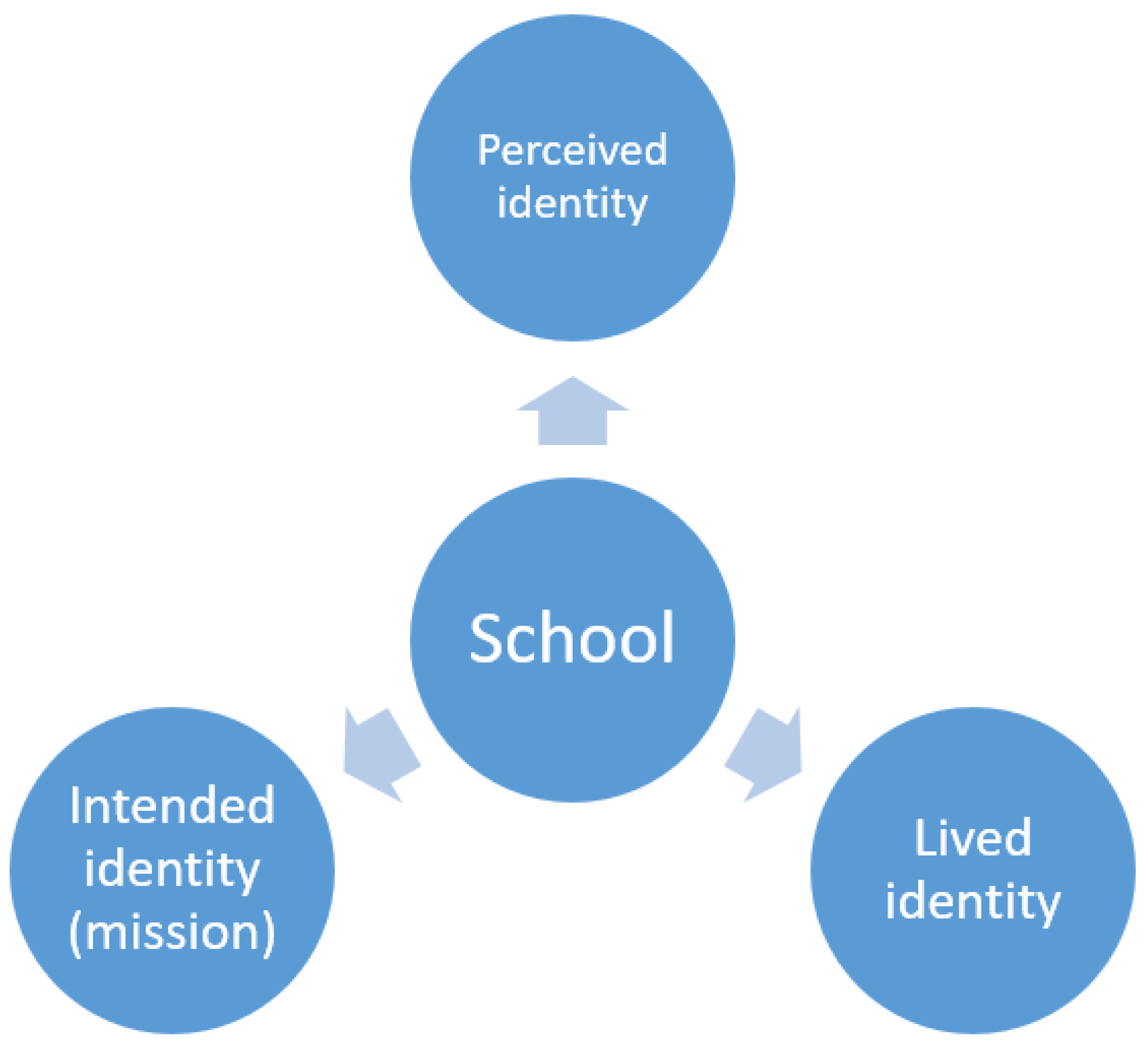

Pazmiño 2008, p. 14). One of the entry points for doing so is to zoom in on the potential discrepancy between the intended and the lived identities. Bringing to light these differences opens perspectives for the renewal of existing practices (

Edlin 2010;

Smith 2018). What is lived out reveals what is really thought and felt below the surface. “It is the operational which is a much more accurate reflection of the true life and vision of the place” (

Edlin 2014, p. 93). Unfolding the contradictions can be challenging because even a school is usually reluctant to experience itself as incongruent. However, the process is also beneficial because the inconsistency is a reason for reconsidering the school’s mission. The same applies when one compares the perceived identity with the described and lived identity. Every comparison can lead to rethinking the mission.

3.1. Stage 1: Mission Understood as a Unique Calling

3.1.1. Four Approaches

In the previous section, we approached the school’s mission in a formal way. In this section, we consider the same theme in a substantive way. Whether in the case of starting a new school or reconsidering the mission, substantive choices are decisive. Depending on the context, the mission will have different faces. To make the school’s mission explicit, we first discuss four exemplary approaches—socializing, person-centered, transformational, and charity-based—through which the school’s call can be shaped in different ways in the concrete context. The emphasis of each approach is on the Christian community, the individual believer, the influence on society, and the aim to solve the problems in society, respectively. In all four approaches, the claims on truth identified by

Wardekker and Miedema (

2001) can be recognized: claims on religious truth, the nature of education, and the cultural difference. The approaches are not mutually exclusive but overlap. Although several approaches can be used in a school, one of the images is often dominant. Regarding the following subsections, it is important to note that a Christian school is not necessarily private and unsubsidized. This is self-evident in some countries, where the law prescribes that under certain conditions, the state should fully or partly fund religious schools.

3.1.2. Socializing Approach

The first approach can be observed in a school founded by a specific Christian denomination. Often, this is a church congregation or group. The governing idea is that the church, family, and school are in a triangular relationship, where the same goal is pursued. The children who belong to the congregation are considered part of the covenant established by God. According to their (baptismal) promise, parents then have the task of initiating their children into the Christian doctrine. The school is supportive of this pedagogical task. Here, the initiation into the Christian faith takes place, just like it does in the family. Many schools have been founded on the idea that children in the family, church, and school should grow up in the same atmosphere (

Markus et al. 2018). A Christian parent of educator values unity in what is taught to children at home and in school. It is therefore not surprising that after a church splits into several denominations, it sometimes causes the establishment of a new school. The newly formed denomination feels the calling to found a school because it is believed that children cannot be entrusted to teachers who were not pure in their teaching (for an example, see

Spoelstra 2017, p. 118). A possible consequence of this approach is that only the children who belong to the school’s own denomination are admitted as students, but this is not necessarily the case. Many Christian schools are maintained by members of different churches with a related spirituality. This is not due to an equal community in the sense of a formal church but of a community of mentality: a sociological group of Christians who share similar truth claims and a similar life-style. In the socializing approach, the priority lies in the interests of one’s own community, not of society. If the interests in relation to society have to be articulated, the responsible body will defend the right to consolidate one’s own place in it and the preparation of students for a place in this society.

The formation of a school based on the socializing approach sometimes arouses aversion. In an interview, an opponent of Christian education says the following:

Schools are not an instrument for transmitting a certain group identity. Education is not meant to be an extension of parents and to propagate their values. At school, children should learn things that conflict with what they belong to. So that they can form their own opinions.

This quotation strongly conveys the idea from the Enlightenment that the school is an institution that distances the youth from the parental environment.

3.1.3. Person-Centered Approach

The second approach focuses on the student’s individual relationship with God. The school’s primary calling is the spiritual formation of children to help them develop their personal faith in Christ. The theological reasoning for this is stressed by the need for regeneration and conversion. It is the task of a school to do everything to make this possible. Articulations can vary widely, depending on the church denomination or the group of denominations on which the schools are founded. Sometimes, a broader objective is indicated, such as the glorification of God (in accordance with the abridged Westminster Catechism Q/A 1, which states that each person is meant “to glorify God, and to enjoy Him forever”). There are also examples where imitation and discipleship are at the forefront. The website of the American organization that developed the all-Christian curriculum,

Accelerated Christian Education, states that staff at the schools “help students grow closer to the Lord Jesus Christ and demonstrate their achievements in a wide range of categories from chess to Bible, basketball to art”.

1 3.1.4. Transformational Approach

The third approach takes neither the covenant nor the growth of individual faith as its starting point but the function of a school in relation to culture. According to

Edlin (

2014, p. 245), Christians are in danger of retreating to an island; they try to secure the church through schools. In his view, this is against God’s intention for this world; God has given people the mandate to build up and preserve the earth. Moreover, Christ is the ruler of the whole world. Salvation is not only about humanity and the church, but about every square inch of the world. Schools must educate Christian students to be the salt of the earth and shining lights.

Christian cultural engagement (…) is a proactive and winsome calling for all Christians that delight in the majesty of God over his creation and the creative and stewardly lordship that he has given to humankind over the world. And it places the cross of Christ at the centre of all of life. Christian schools ought to prepare students for this type of cultural engagement.

The transformative ideal, in which the transformation of the world is central, implies, even more than the previous approaches, an antithetical attitude toward the prevailing (secular) culture (

Edlin 2014, p. 239). Edlin emphasizes that a Christ-centered approach does not mean a concentration on the relationship with Christ but on the

world of Christ: “Christian education does not spend all its time looking at the Son; instead, it looks at the world and our places and tasks in it in the light that the Son provides” (pp. 41, 53). Elsewhere,

Edlin (

2010, p. 98) states that “the nation-building goal of these Christian schools is to equip children to discern what is best (Philippians 1: 9–11), including a peaceful and robust cultural critique and transformation in the name of Christ”.

3.1.5. Charity-Oriented Approach

Many public schools around the world, founded by Christians, started from the ideal of solving social problems, for example, by providing education where there was no school. This happened, for instance, in developing countries, often with the support of aid organizations. From the school founders’ perspective, the social interest in establishing a school was the priority. Sometimes, they had not yet got around to thinking about the Christian content of education. In contexts where education is common, Christians also establish schools from charitable reasons, for example, when education pays little attention to children with learning difficulties or to students’ moral development. We call this the charity-oriented approach, referring to the charitable drive of Christians because they perceive the school’s mission as serving vulnerable groups in society.

3.1.6. Evaluating the Four Approaches

As stated, the approaches are not mutually exclusive but overlap. Many Christian schools have something of all four approaches. The socializing approach honors the place of the covenant and the baptismal promise. The person-centered approach has an eye for the awkwardness and the subtlety of faith and salvation appropriation. The positive aspects of the transformational approach are its intention to eliminate dualism and its mandate to make Christian faith relevant to everyday life. The charity-oriented approach shows the Christians’ sensitivity to the needs of the world, which is very important with regard to civic duty.

However, all approaches have their limitations as well. The socializing approach can be very inward-looking, limited to a small community, with no regard for society. The person-centered approach may focus too much on the inner self, without paying attention to concrete action. The transformational approach may suggest social engineering and optimism. For this reason, it runs the risk of insufficiently acknowledging sin and brokenness and may suggest that serving God is simply a given instead of a learning journey that finds security in divine providence. Finally, the charity-oriented approach might run the risk of eliminating religious education or not paying attention to the Christian meaning in school subjects. If all approaches’ merits and limitations are taken seriously, they can be helpful in the reflection on the school’s mission.

3.3. Stage 3: How to Contextually Revitalize the School Identity

Having described some exemplary approaches of a school mission (stage 1) and clarified the dynamics of revitalization (stage 2), we now propose the steps that can be followed on the road to a revitalized mission. These steps, pictured in

Figure 3, are successively about the urgency, the starting point, the population, the law, the tradition of the school, the cultural issues that are observed, and the interests of the family, church, and society. The steps are based on the earlier research described by

De Muynck et al. (

2017). It is conceivable that a school board, a school team, and possibly other people involved follow the steps, but these do not necessarily happen in the presented sequence. The seven steps are about the content in the process of sense-giving, action formation, sense-making, and institutionalization. In meetings, one can choose different work formats, varying from reflecting individually to weighing thoughts together. In the process of jointly discerning what is important in the given circumstances, the stakeholders need to decide what needs to be changed and what the future actions in the school should look like. Does their calling take into account the interests of the future generation?

3.3.1. What Is the Urgency?

We can determine what is urgent by means of the four approaches, as described in stage 1. As we have seen, none of them are exclusive; however, they are valid as the first step in determining one’s preferred position. One can focus on the Christian community, concentrate on faith appropriation or character development, have a school that aims to further the Christian influence on culture, or place a charitable motive in front. When the situation changes, the question of urgency must be raised again. The school may change its preferences due to the changes in its population. The types of students change, and the types of parents change, which in turn alters the whole pedagogical setting. Another influence constitutes the changing expectations from society (politically driven or resulting from cultural trends). For example, the government might ask schools to pay more attention to their public presentation. This requirement can be based on the idea that if the government finances a diversity of schools, the latter must also clarify how their profiles are translated into classroom activities. This requires maneuverability of both the management and the staff.

3.3.2. Which Entry?

The next question is about the point of entry that one chooses. First, one can select the entrance of the student. The question is then what kind of students one strives for at the end of their schooling. If this entrance is chosen, the school’s policy is determined by the exit profiles of the students. A school will preferably choose this entrance in case of a person-oriented approach if prioritized in the urgency step. A school can work with a specific set of virtues, for example, responsibility, respect, and reliability. The second point of entry can be the curriculum: what does the school want to convey, and how much worldview should the content include? There are schools in disadvantaged situations that focus strongly on basic skills. Other schools, in more favorable circumstances, stress the use of Christian-designed methods. The third input can be a specific didactic approach. In this case, the school chooses a concept, sometimes an existing one, that is integrated into the Christian school. For example, there are Christian schools that consider development-oriented education, based on Vygotsky’s philosophy, as compatible with their Christian principles. The fourth point of entry is the teacher. School boards can defend their position that the teachers’ high level of knowledge determines the quality of education and the Christian character of the school. In this case, they will invest heavily in professionalization.

3.3.3. What Is the Population?

One of the decisive factors in the context in which the school operates is demographic development. Which students does the school serve or want to serve? After all, in primary education, goals differ by age and target group, and in higher education, they vary by subject area—types of professions and types of academic disciplines. The population may be prosperous but also marked by poverty. In a wealthy environment, it may be possible to start a public school, whereas in other environments, one is totally dependent on government funds or charities. Cultural characteristics are closely related to the population. The language levels with which children enter school are usually strongly correlated with the educational levels of their parents. The question is which need is observed in the population. For example, a school in a prosperous metropolitan area may observe that many children feel lonely and may consequently decide to focus on strong contacts with the parents. A school in a large Asian city’s slum area can also focus on parent contacts but mainly with the intention of providing extra training for parents.

3.3.4. What Are the Possibilities and Limits in the Law?

The legislation of a country limits or opens possibilities. In many countries, there is a state curriculum, and it is not possible to teach religion in state-funded schools. For some Christian communities, this does not prevent them from establishing a school. They organize prayer meetings at teachers’ homes, and religious education is taught in the families. As mentioned above, some countries have a great deal of freedom in setting up schools, organizing education, and shaping the curriculum. Legislation may impose qualification requirements on staff or requirements relating to the minimum number of students. However, schools must sometimes also take into account the requirements regarding content, such as attention to the prescribed democratic core values in citizenship education.

3.3.5. How Does One Use the Potential of One’s Own Tradition?

When shaping Christian education, one cannot disregard the historically developed context. The community in which the target group is situated has its own tradition, with its own leaders and role models who have made the community flourish. Traditions have their own potentials, sometimes limiting choices; at other times opening possibilities. The school must take these into account because the target groups (parents and students) must feel safe in school. At the same time, a tradition offers sources to re-evaluate current school practice. When a school was founded, careful thought was given to its name. As a result, schools often have meaningful names. Where possible, a connection between the name and the teaching content or the school culture is a good entry point. In this way, the Timothy School can measure itself against what Paul says to Timothy in his pastoral letters when re-evaluating its tradition. A Rehoboth school can thematize getting the space given by God for the school culture (Genesis 26: 22).

3.3.6. To Which Cultural Issues Will the School Respond?

This brings us to cultural criticism. Besides internal cultural criticism (critical reflection on one’s own Christian community), a culture-critical view is a basic competence of the Christian community. Whereas in the beginning of the 20th century, Christian education had to relate to the emerging reform pedagogy (e.g., see

Bavinck 1928, p. 123), and since the turn of the century, to the dominance of constructivism, there are now other dominant movements in which one has to choose one’s position. First, one can think of the major influence of performative thinking that still leads to strong efficiency and performance drive (

Biesta 2010). Second, the rapid advance of information and communication technology greatly increases the number of didactic tools available and necessitates a reassessment of the role of the teacher. Third, a lot of developments are going on internationally. Populism and nationalism are on the rise, and there is a great need to make students politically aware and resilient. Finally, one can think of the strong secularization of the whole society, which makes the way of perceiving things in the dominant culture naturalistic, positivistic, and anti-metaphysical.

3.3.7. What Is the Right Balance between the Stakeholding Institutions?

The ideal of the Christian school can be pictured as an institution between the church, family, and government. The interests of the government must in some way be balanced with those of Christian families and church communities (

Exalto 2012, pp. 173–87). In every context, the Christian school has to deal with the three stakeholders. Education aims to form students into Christian citizens (interest of the state), prepares them for responsibility in the private sphere (the interest of the family), and invites them to become faithful believers (interest of the church). The school cannot be given the role of a neutral institution that objectively allows the student to take up an autonomous position but has to count with values originating from the family socialization and with educational ideals in the religious sphere.