Spatio-Temporal Process of the Linji School of Chan Buddhism in the 10th and 11th Centuries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Resurgence of the Linji Monastic Order

2.1. The Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Generations of Linji

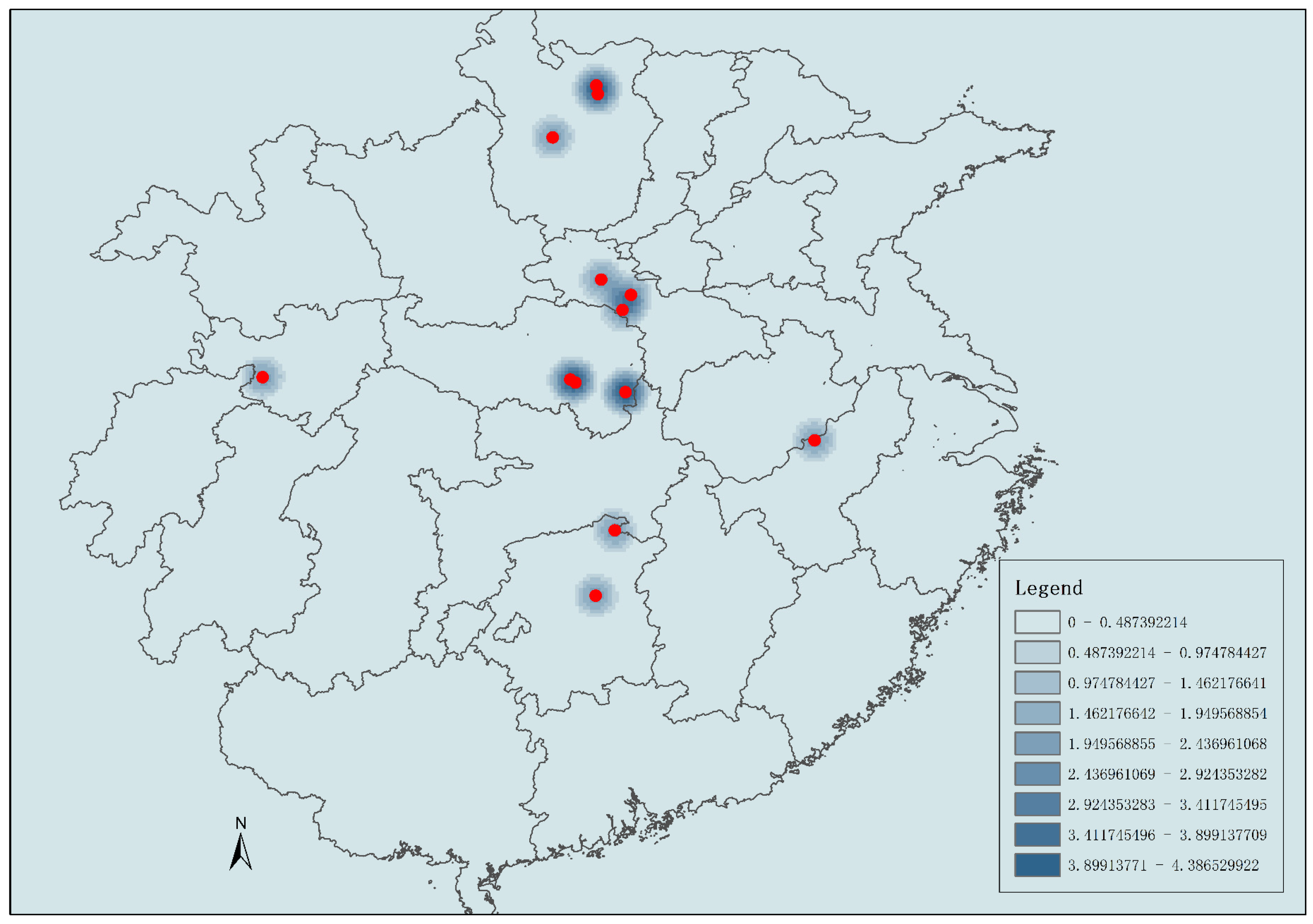

2.2. The Seventh Generation of Linji

3. The Southward Movement of the Eighth Linji Generation and Ideological Divergence

4. The Flourishing of the Linji Monastic Order and Founding of Huanglong School

4.1. The Ninth Generation of Linji

4.2. The 10th Generation of Linji

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | |

| 2 | In the “Chan Garden Regulations” Volume 7 “Regulation for Abbot”, it is stated: “To represent the Buddha in giving sermons and manifesting extraordinary knowledge, this is called ‘transmitting the Dharma’; to continue the Buddha’s wisdom and life in various places, this is called ‘abiding in the Dharma’. The first turning of the Dharma wheel is life-changing; with an authentic lineage, one is called a ‘transmitter of the lamp’ (代佛揚化,表異知事,故雲傳法;各處一方,續佛慧命,斯曰住持。初轉法輪,命為出世;師承有據,乃號傳燈)” (Zong and Liu 2020). |

| 3 | The phenomenon of the first seat entering the Lamp History is strange, and Schlütter is also puzzled by this. One possible speculation is that these first seats who entered the Lamp History later became the abbots. For example, Daoqiong(道瓊), the inheritance disciple of 10th generation Letan Jingxiang (泐潭景祥), became the first abbot of Chaohe Temple (超化寺) in Xinzhou after it was reformed into a Chan temple in 1140. See (Zhengshou 1975c). |

| 4 | The Xu Chuandenglu lists Qicong (契聰) as Shoushan’s inheritance disciple, based on the Wudeng Huiyuan, which recorded that when Shoushan passed away and the monks and laypeople of Xihe County dispatched a monk, Qicong, to greet Fenyang Shanzhao as the abbot, he said, “The Chan master Fengxue Yanzhao was afraid that the bad prophecies would be fulfilled, and was worried that the tenets of our school would be lost. Fortunately, his late master, Shoushan Shengnian, came out to be the abbot of the school and espoused the sermons” (Puji 1984a). |

| 5 | The Xu Chuandenglu lists Chengxiang Wangsui (丞相王隨) as a member of the inheritance disciples of the Shoushan Shengnian, but he is not responsible for spreading the Dharma transmission. The Xu Chuandenglu also lists Chan Master Fusheng Shantao (福聖善瑫) as the inheritance disciple of Shoushan Shengnian, but it lacks geographic information. The map actually shows the distribution of the 13 inheritance disciples of the Shoushan. The mutual preaching interval of the Linji sixth generation is 1006–1023. For the presumed time of propagation of the Linji sixth Chan masters, see Ge, Zhouzi, “Spatial Flows of Chan Generation in Jiangnan during the Five Dynasties and Northern Song Dynasty (五代北宋時期江南地區禪宗法脈的空間流動)”, Ph.D. dissertation, Fudan University: Shanghai, 2016, p. 177. |

| 6 | According to the catalogue of the Tiansheng Guangdenglu, Li Zunxu and Yang Yi were both of the third generation of Shoushan and studied under Guyin Yuncong and Guanghui Yuanlian, respectively. On the relationship between Li Zunxu and his son and the development of Chan Buddhism, see (Huang 1997b). |

| 7 | This is especially represented by Guyin Yuncong. Volume 1 of Zimen Jingxun (緇門警訓) records that Zhadao (查道, 955–1018) said of himself: ”In spring, there was a disciple of Yuncong’s (蘊聰), named Huiguo (慧果), who came to Kaifeng and showed me Yuncong’s letter”. The Tiansheng Guangdenglu, vol. 18, Jueyuan Shangzuo (覺圓上座), records that Jueyuan, a disciple of Yuncong, traveled from Guyin Mountain to the capital city with a letter “to the residence of Li Zunxu, the prince consort of the emperor” (Rujin 1924; Li 1975a). |

| 8 | According to the catalogue of Tiansheng Guangdenglu, four disciples of Shoushan were given the purple kasaya. According to the Inscription on the Pagoda of Commemorated Chan Master Cizhaocong (with preface) (先慈照聦禪師塔銘(并序)) written by Li, Zunxu, Guyin Yuncong was also given the purple kasaya. |

| 9 | The inheritance disciple Monk Puzhao (普照) of Guyin Yuncong and the inheritance disciple Monk Lingyan Wenzhi (靈岩文智) of Shending Hongjian lack geographic information, and the map actually shows 69 people. The mutual preaching period of the seventh Linji Chan masters is from 1025 to 1039. For the process of determining the time of the seventh Linji Chan masters’ propagation, see (Ge 2016, pp. 179–180). |

| 10 | The geographical information on the prefectures of the four inheritance disciples of Shishang Chuyuan, namely Yongle Yue (永樂悅), Jianfu Cen (薦福岑), Puzhao Xiujie (普照修戒), Yongshang Zuo (永上座), and the inheritance disciple of Langya Huijue, namely Yuquan Wuben (玉泉務本), are missing. The chart actually shows the distribution of the 168 people who passed on the Dharma. The common transmission time interval of the eighth Linji Chan Masters is 1049–1062. For the process of deducing the time of propagation of the eighth Linji Chan masters, see (Ge 2016, pp. 182–183). |

| 11 | In the book written in the Northern Song Dynasty, “Six Inheritance Disciples of Jiangshan Juehai Chan Master, Jinling Prefecture (金陵蔣山覺海)” the catalog of Jianzhong Jingguo Xudenglu Zhangzhi lists Shimen Ya (Weibai 1975f). Jiatai Pudenglu, written in the Southern Song Dynasty, Chapter 4, “Two Inheritance Disciples of Jiangshan Zanyuan Chan Master”, lists Xuedou Faya as one of the two inheritance disciples (Zhengshou 1975b). This is because Faya first lived in Shimen, Quzhou Prefecture, and then moved to Xuedu, Mingzhou Prefecture. |

| 12 | The geographic information on the prefectures where the five people of Yunfeng Wenyue (雲峰文悅)’s inheritance disciple Guo Shanlin (郭山霖), Jinyin Daozhen’s inheritance disciple Jinyuan (淨圓), and Huanglong Huinan’s inheritance disciples Taiping Yao (太平瑤), Zhangjiang Yuan (章江元), and Xingguo Qing (興國傾) were located is missing and cannot be shown on the map. Therefore, the map actually shows the distribution of 164 Chan masters. Linji ninth Chan masters do not have a mutual preaching interval; it is set as about 1070. See (Ge 2016, pp. 190–191). |

| 13 | Dawei Muzhe’s inheritance disciple, Jiayou Bian (嘉祐辯), Baizhang Yuansu’s inheritance disciple, Lu Yuanye (鹿苑業), Donglin Changzong’s inheritance disciple, Qianming Zaichang (乾明載昌), Huangbo Weisheng’s inheritance disciple, Mazu Huayan (馬祖懷儼), Huanglong Zuxin’s inheritance disciples, Xinghua Yan (興化演), Wuwei Weicong (無為維琮), Xifeng Su (西峰素), Chanlin Xiguang (禪林希廣), and Yichan Shangzuo (意禪上座), Jianlong Zhaocheng’s inheritance disciple, Liquan Chu’an (澧泉處安), Letan Hongying’s inheritance disciple, Baoxiang Yong (寶相湧), Baoning Renyong’s inheritance disciple, Xitang Xian (西堂顯), Yunju Yuanyou’s inheritance disciple, Xingdei Xian (興得賢), Yungai Shouzhi’s inheritance disciple, Daning Ji (大寧紀), Sanzushan Fazong’s (三祖山法宗) inheritance disciple, Dongshan Yuan (洞山淵), Fayan’s (fourth Chan master) inheritance disciple, Nanchan Chang (南禪暢), and Yousheng Faju’s (祐聖法居) inheritance disciples Zhidu Yi (智度一) and Ruiyan Zhi (瑞岩智) totaled 18 Chan masters, whose geographical information is missing. Therefore, the map actually shows the distribution of the 337 Linji 10th Chan masters. The dates of the opening of the Dharma of the 10th Linji Chan masters range from about 1080 to 1115, a difference of one generation. Therefore, it is impossible to know the actual time of the 10th Linji Chan masters. The common preaching time of the 10th Rinzai is set at the end of the Northern Song Dynasty; see (Ge 2016, p. 196). |

| 14 | Zhang, Shangying 張商英 Huanglong Chongen Chanyuan Ji 黃龍崇恩禪院記 [Record of Huanglong Chongen Cloister] (Huang 1997a). For the development of the Huanglong School, see Abe, Chōichi 阿部肇 一Soudai Kouryohai no Hatsuten—Kouryo Enan nitsuite, 宋代黃竜派の発展--黃竜慧南について. Journal of Historical Studies 駒沢史學 1962, pp. 32–39 (Abe 1991). |

References

- Abe, Chōichi 阿部肇一. 1991. Zhongguo Chanzong Shi Nanzong Chan Chengli Yihou De Zhengzhi Shehui Shi De Kaozheng 中國禪宗史——南宗禪成立以後的政治社會史的考證 [Research in the History of the Chinese Zen School—An Investigation of the Political and Social History of Southern Zen After Its Establishment]. Translated by Shiqian Guan 關世謙. Taipei: The Grand East Book Co., Ltd. 東大圖書股份有限公司. Available online: https://book.douban.com/subject/7067906/ (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Albert, Welter. 2006. Monks, Rulers, and Literati: The Political Ascendancy of Chan Buddhism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Gaohua 陈高华. 2014. Yuan Chengzong He Fojiao 元成宗與佛教 [Yuan Chengzong and Buddhism]. Journal of Chinese Historical Studies 中國史研究 4: 157–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chuyuan楚圆. 2014. Fenyang Wude Chanshi Yulu 汾陽無德禪師語錄 [Fenyang Wude Zen Master’s Quotations]. In Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經. Edited by Junjirō Takakusu 高楠順次郎 and Kaigyoku Watanabe 渡邊海旭. Tokyo: Taishō shinshū daizōkyō kankōkai/Daizō shuppan, vol. 47, p. 595a. [Google Scholar]

- Faure, Bernard. 1986. Bodhidharma As Textual and Religious Paradigm. History of Religions 25: 187–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ge, Zhouzi 葛洲子. 2016. Wudai Beisong Shiqi Jiangnan Diqu Chanzong Famai De Kongjian Liudong 五代北宋時期江南地區禪宗法脈的空間流動 [Spatial Flows of Zen Lineage in Jiangnan during the Five Dynasties and Northern Song Dynasty]. Ph.D. dissertation, Fudan University, Shanghai, China. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Zhouzi 葛洲子. 2017. Wudai Beisong Shiqi Chanzong De Teshu Sifa—Yi Chanlin Sengbaozhuan Wei Zhongxin 五代北宋時期禪宗的特殊嗣法——以《禪林僧寶傳》為中心 [The Special Succession of Zen Buddhism in the Five Dynasties and Northern Song Dynasty—Centred on the Biography of the Zen Monks]. Buddhist Studies 佛學研究 2: 230–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Zhouzi 葛洲子. 2023. Beisong Yunmen Sengtuan Xingsheng De Shikong Guocheng Jiqi Yuanyin 北宋雲門僧團興盛的時空過程及其原因 [Spatio-temporal Process and Its Causes of the Yunmen Buddhist Community Prosperity in the Northern Song Dynasty]. Journal of Chinese Historical Geography 中國歷史地理論叢 38: 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Shi 胡适. 1991. Zhonguo De Chan: Tade Lishi He Fangfa 中國的禪:它的歷史和方法 [Zen in China: Its History and Methods]. In Zhongguo Chanzong Daquan 中國禪宗大全 [The Complete Book of Chinese Zen]. Edited by Miao Li 李淼. Changchun: Changchun Press, p. 966. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Jun 黄君. 1997. Huanglongzong Zuting Huanglongsi Kao 黃龍宗祖庭黃龍寺考 [Study of Huanglong Temple, the Ancestral Home of Huanglong Sect]. Buddhist Studies 佛學研究, 119–23. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Qijiang 黃啟江. 1997. Beisong Fojiao Shilun Gao 北宋佛教史論稿 [A Treatise on the History of Buddhism in the Northern Song Dynasty]. Taipei: Commercial Press, p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Tingjian 黃庭堅. 2001. Fuchangxin Chanshi Taming 福昌信禪師塔銘 [Inscription on Zen Master Fuchangxin’s Pagoda]. In Huang Tingjian Quanji 黄庭坚全集 [The Complete Works of Huang Tingjian]. Chengdu: Sichuan University Press, vol. 2, p. 855. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Xinchuan 黄心川, and Zhiqiang Ju 鞠志强. 2011. Linji Zong De Fuxing Yu Qianzhan 臨濟宗的復興與前瞻 [Linji School’s Resurgence and Prospect]. Tribune of Education Culture 教育文化論壇 3: 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huihong惠洪. 1975a. Baoben Yuan Chanshi 報本元禪師 [The Zen Master Baoben Yuan]. In Chanlin Sengbao Zhuan 禪林僧寶傳 [Biography of the Zen Monks]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照 and Giyū Nishi 西義雄. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 29, p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- Huihong惠洪. 1975b. Ciming Chanshi 慈明禪師 [The Zen Master Ciming]. In Chanlin Sengbao Zhuan 禪林僧寶傳 [Biography of the Zen Monks]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 21, pp. 140, 142, 143, 145. [Google Scholar]

- Huihong惠洪. 1975c. Dawei Zhenru Zhe Chanshi 大溈真如喆禪師 [The Zen Master Dawei Zhenru Zhe]. In Chanlin Sengbao Zhuan 禪林僧寶傳 [Biography of the Zen Monks]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 25, p. 167. [Google Scholar]

- Huihong惠洪. 1975d. Fenzhou Taizi Zhao Chanshi 汾州太子昭禪師 [The Zen Master Taizi Zhao in Fenzhou Prefecture]. In Chanlin Sengbao Zhuan 禪林僧寶傳 [Biography of the Zen Monks]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 3, p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Huihong惠洪. 1975e. Huanglong Nan Chanshi 黃龍南禪師 [The Zen Master Huanglong Nan]. In Chanlin Sengbao Zhuan 禪林僧寶傳 [Biography of the Zen Monks]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 22, pp. 149–50. [Google Scholar]

- Huihong惠洪. 1975f. Jiangshan Yuan Chanshi 蔣山元禪師 [The Zen Master Jiangshan Yuan]. In Chanlin Sengbao Zhuan 禪林僧寶傳 [Biography of the Zen Monks]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 27, pp. 148–49. [Google Scholar]

- Huihong惠洪. 1975g. Jinshan Daguan Yin Chanshi 金山達觀頴禪師 [The Zen Master Daguan Yin in Jin Mountain]. In Chanlin Sengbao Zhuan 禪林僧寶傳 [Biography of the Zen Monks]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 27, p. 187. [Google Scholar]

- Huihong惠洪. 1975h. Ruzhou Shoushan Nian Chanshi 汝州首山念禪師 [The Zen Master Shoushan Nian in Ruzhou Prefecture]. In Chanlin Sengbao Zhuan 禪林僧寶傳 [Biography of the Zen Monks]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 3, pp. 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Huihong惠洪. 1975i. Shending Yin Chanshi 神鼎諲禪師 [The Zen Master Shending Yin]. In Chanlin Sengbao Zhuan 禪林僧寶傳 [Biography of the Zen Monks]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 14, p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- Huihong惠洪. 1975j. XInghua Xian Chanshi 興化銑禪師 [The Zen Master Xinghua Xian]. In Chanlin Sengbao Zhuan 禪林僧寶傳 [Biography of the Zen Monks]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 18, p. 128. [Google Scholar]

- Huihong惠洪. 1975k. Xiyu Duan Chanshi 西余端禪師 [The Zen Master Xiyu Duan]. In Chanlin Sengbao Zhuan 禪林僧寶傳 [Biography of the Zen Monks]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 19, p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Huihong惠洪. 2012a. Chongxiu Sengtang Ji 重修僧堂記 [Memoirs of the Restoration of the Sangha]. In Zhu Shimen Wenzi Chan 注石門文字禪 [The Complete Works of Huihong with Annotates]. Riben Songdai Wenxve Yanjiu Congkan 日本宋代文學研究叢刊 [Japanese Song Dynasty Literature Research Series]; Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, vol. 21, p. 1302. [Google Scholar]

- Huihong惠洪. 2012b. Huayao Ying Chanshi Xingzhuang 花藥英禪師行狀 [Brief Biographical Sketch of the Deceased Zen Master Huayao Ying]. In Zhu Shimen Wenzi Chan 注石門文字禪 [The Complete Works of Huihong with Annotates]. Riben Songdai Wenxve Yanjiu Congkan 日本宋代文學研究叢刊 [Japanese Song Dynasty Literature Research Series]; Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, vol. 30, p. 1694. [Google Scholar]

- Huihong惠洪. 2012c. Letan Huai Chanshi Xingzhuang 泐潭准禪師行狀 [Brief Biographical Sketch of the Deceased Zen Master Letan Huai]. In Zhu Shimen Wenzi Chan 注石門文字禪 [The Complete Works of Huihong with Annotates]. Riben Songdai Wenxve Yanjiu Congkan 日本宋代文學研究叢刊 [Japanese Song Dynasty Literature Research Series]; Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, vol. 30, p. 1691. [Google Scholar]

- Huihong惠洪. 2012d. Sanjiao Jie Chasnhi Shou Taming Bingxu 三角劼禪師壽塔銘(並序) [Inscription on the Pagoda of Zen Master Sanjiao Jie (with preface)]. In Zhu Shimen Wenzi Chan 注石門文字禪 [The Complete Works of Huihong with Annotates]. Riben Songdai Wenxve Yanjiu Congkan 日本宋代文學研究叢刊 [Japanese Song Dynasty Literature Research Series]; Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, vol. 29, p. 1674. [Google Scholar]

- Huihong惠洪. 2012e. Yuelu Hai Chanshi Taming Bingxu 岳麓海禪師塔銘(並序) [Inscription on the Pagoda of Zen Master Yuelu Hai (with preface)]. In Zhu Shimen Wenzi Chan 注石門文字禪 [The Complete Works of Huihong with Annotates]. Riben Songdai Wenxve Yanjiu Congkan 日本宋代文學研究叢刊 [Japanese Song Dynasty Literature Research Series]; Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, vol. 29, pp. 1675–76. [Google Scholar]

- Juding居頂. 1924. Chengdu Fu Zhaojue Chunbai Chanshi 成都府昭覺純白禪師 [Zhaojue Chunbai, the Zan Master in Chengdu Prefecture]. In Xuchuan Denglu 續傳燈錄 [The Sequel to the Lamp History]. Edited by Junjirō Takakusu 高楠順次郎 and Kaigyoku Watanabe 渡邊海旭. Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經. Tokyo: Taishō shinshū daizōkyō kankōkai/Daizō shuppan, vol. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Gou 李覯. 2011. Xudenglu and Taiping Xingguo Chanyuan Shifang Zhuichiji 大平興國禪院十方住持記 [Record of the Abbots in Taiping Xingguo Cloister]. In Ligou Ji 李覯集 [Li Gou’s Complete Works]. Zhongguo Sixiangshi Ziliao Congkan 中國思想史資料叢刊 [Chinese Thought History Series]; Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zunxu 李遵勗. 1975a. Jueyuan Shangzuo 覺圓上座 [The Head Seat Juanyuan]. In Tianshengguang Denglu 天聖廣燈錄 [Tianshengguang Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 18, p. 511b. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zunxu 李遵勗. 1975b. Ruzhou Baoying Chanyuan Shengnian Chanshi 汝州寶應禪院省念禪師 [Shengnian, the Zen Master in Baoying Cloister, Ruzhou Prefecture]. In Tianshengguang Denglu 天聖廣燈錄 [Tianshengguang Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 16, p. 493c. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zunxu 李遵勗. 1975c. Xianci Zhaocong Chanshi Taming Bingxu 先慈照聦禪師塔銘(并序) [Inscription on the Pagoda of Commemorated Zen Master Cizhaocong (with Preface)]. In Tianshengguang Denglu 天聖廣燈錄 [Tianshengguang Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 17, p. 501a. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zunxu 李遵勗. 1975d. Xiangzhou Guyinshan Yuncong Cizhao Chanshi 襄州穀隱山蘊聰慈照禪師 [Yuncong Cizhao, the Zen Master in Guyin Mountain, Xiangzhou Prefecture]. In Tianshengguang Denglu 天聖廣燈錄 [Tianshengguang Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 78, p. 499b. [Google Scholar]

- McRae, John R. 1986. The Northern School and the Formation of Early Ch’an Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morten, Schlütter. 2008. How Zen Became Zen: The Dispute over Enlightenment and the Formation of Chan Buddhism in Song-Dynasty China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi, Yoshitaka 野口善敬. 2005. Yuandai Chanzong Shi Yanjiu 元代禪宗史研究 [Studies on the History of Zen Buddhism in the Yuan Dynasty]. Kyoto: The Insititute For Zern Studies 禪文化研究所. Available online: https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA72942430 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Protass, Jason. 2016. Lineages, Networks, and the Lamp Records. Review of Religion and Chinese Society 3: 164–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puji普濟. 1984a. Fenzhou Taiziyuan Shanzhao Chanshi 汾州太子院善昭禪師 [Shanzhao, the Zen Master in Princely Cloister, Fenzhou Prefecture]. In Wudeng Huiyuan 五燈會元 [A Brief Version of Five Zen Lamp History]. Zhongguo Fojiao Dianji Xuankan 中國佛教典籍選刊 [Selected Chinese Buddhist Texts]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, vol. 11, pp. 684–85. [Google Scholar]

- Puji普濟. 1984b. Kaishan Daoqiong Chanshi 開善道瓊禪師 [Kaishan Daoqiong Zen Master]. In Wudeng Huiyuan 五燈會元 [A Brief Version of Five Zen Lamp History]. Zhongguo Fojiao Dianji Xuankan 中國佛教典籍選刊 [Selected Chinese Buddhist Texts]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, vol. 12, p. 772. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Guan 秦观. 1994a. Zhiming Qingchanshi Taming 志铭·庆禅师塔铭 [Epitaph on the Pagoda of Zen Master Qing]. In Huaihai Jijianzhu 淮海集箋注 [Huaihai Collection and Commentaries]. Zhongguo Dudian Wenxve Congshu 中國古典文學叢書 [Chinese Classical Literature Series]; Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing House, vol. 28, p. 1082. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Guan 秦观. 1994b. Zhuang 状 [Accusation]. In Huaihai Jijianzhu 淮海集箋注 [Huaihai Collection and Commentaries]. Zhongguo Dudian Wenxve Congshu 中國古典文學叢書 [Chinese Classical Literature Series]; Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing House, vol. 36, pp. 1179–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rujin如巹. 1924. Cizhaocong Chanshi Zhu Xiangzhou Shimen Qingcha Daizhi Weizhuan Sengtang Ji 慈照聰禪師住襄州石門請查待制為撰僧堂記 [Record of the Sangha Hall of Zen Master Cizhaocong, Who Lived in Shimen Mountain, Xiangzhou Prefecture]. In Zimen Jingxun 緇門警訓 [A Cautionary Note For Monks]. Edited by Junjirō Takakusu 高楠順次郎 and Kaigyoku Watanabe 渡邊海旭. Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經. Tokyo: Taishō shinshū daizōkyō kankōkai/Daizō shuppan, vol. 48, p. 1072b. [Google Scholar]

- Shijiao師皎. 1975. Duan Chanshi Xingye Ji 端禪師行業記 [Zen Master Duan’s Activity Journal]. In Wushan Jingduan Chanshi Yulu 吳山淨端禪師語錄 [Wu Mountain Jingduan Zen Master’s Quotations]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 73, p. 83b. [Google Scholar]

- Tetsuo, Suzuki 鈴木哲雄. 2006. Chūgoku Zen Shō Jimē Sanmē Jiten 中國禪宗寺名山名辭典 [A Dictionary of the Names of Chinese Chan Temples and Mountains]. Tokyo: The Sankibo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya, Taisuke 土屋太祐. 2008. Beisong Chanzong Sixiang Jiqi Yuanyuan 北宋禪宗思想及其淵源 [Chan Thought in the Northern Song and its Origins]. Chengdu: Bashu Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Weibai惟白. 1975a. Dengzhou Xiangyan Shan Huizhao Chanshi Dongfu 鄧州香嚴山慧照禪師洞敷 [Huaizhao Dongfu, the Zen Master in Xiangyan Mountain, Dengzhou Prefecture]. In Jianzhong Jingguo Xudenglu 建中靖國續燈錄 [Continued Jianzhong Jingguo Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 14, p. 729c. [Google Scholar]

- Weibai惟白. 1975b. Dongjing Daxiaongguo Si Zhihai Chanyuan Zhengru Chanshi 東京大相國寺智海禪院真如禪師 [Zhengru, the Zen Master in Daxiangguo Temple, Zhihai Cloister, National Capital]. In Jianzhong Jingguo Xudenglu 建中靖國續燈錄 [Continued Jianzhong Jingguo Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 14, p. 726a. [Google Scholar]

- Weibai惟白. 1975c. Fuzhou Bailu Shan XIanduan Chanshi 福州白鹿山顯端禪師 [Xianduan, the Zen Master in Bailu Mountain, Fuzhou Prefecture]. In Jianzhong Jingguo Xudenglu 建中靖國續燈錄 [Continued Jianzhong Jingguo Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 7, p. 684c. [Google Scholar]

- Weibai惟白. 1975d. Fuzhou Shengquan Si Shaodneg Chanshi 福州聖泉寺紹登禪師 [Shaodeng, the Zen Master in Shengquan Temple, Fuzhou Prefecture]. In Jianzhong Jingguo Xudenglu 建中靖國續燈錄 [Continued Jianzhong Jingguo Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 14, pp. 731a, 731b. [Google Scholar]

- Weibai惟白. 1975e. Hongzhou Huanglong Shan Chongen Huinan Chanshi 洪州黃龍山崇恩惠南禪師 [Chongen Huinan, the Zen Master in Huanglong Mountain, Hongzhou Prefecture]. In Jianzhong Jingguo Xudenglu 建中靖國續燈錄 [Continued Jianzhong Jingguo Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 7, p. 678c. [Google Scholar]

- Weibai惟白. 1975f. Jinling Jiangshan Juehai Chanshi Fasi Liuren 金陵蔣山覺海禪師法嗣六人 [Six Inheritance Disciples of Jiangshan Juehai Zen Master, Jinling Prefecture]. In Jianzhong Jingguo Xudenglu 建中靖國續燈錄 [Continued Jianzhong Jingguo Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 2, p. 630b. [Google Scholar]

- Weibai惟白. 1975g. Jinling Jiangshan Juehai Chanshi 金陵蔣山覺海禪師 [Jiangshan Juehai, the Zen Master in Jinling Prefecture]. In Jianzhong Jingguo Xudenglu 建中靖國續燈錄 [Continued Jianzhong Jingguo Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 7, p. 681b. [Google Scholar]

- Weibai惟白. 1975h. Junzhou Huangbo Zhengjue Weisheng Chanshi 筠州黃檗真覺惟勝禪師 [Huangbo Zhengjue Weisheng, the Zen Master in Junzhou Prefecture]. In Jianzhong Jingguo Xudenglu 建中靖國續燈錄 [Continued Jianzhong Jingguo Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 12, p. 715a. [Google Scholar]

- Weibai惟白. 1975i. Luzhou Xinghua Renyue Chanshi 廬州興化仁岳禪師 [Xinghua Renyue, the Zen Master in Luzhou Prefecture]. In Jianzhong Jingguo Xudenglu 建中靖國續燈錄 [Continued Jianzhong Jingguo Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 8, p. 687c. [Google Scholar]

- Weibai惟白. 1975j. Quanzhou Kaiyuan Si Zhengjue Dashi 泉州開元寺真覺大師 [Zhengjue, the Zen Master in Kaiyuan Temple, Quanzhou Prefecture]. In Jianzhong Jingguo Xudenglu 建中靖國續燈錄 [Continued Jianzhong Jingguo Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 19, p. 765c. [Google Scholar]

- Weibai惟白. 1975k. Yuanhzhou Yangqi Shan Putong Chanyuan Fanghui Chanshi 袁州楊岐山普通禪院方會禪師 [Fanghui, the Zen Master in Putong Cloister, Yangqi Mountain, Yuanzhou Prefecture]. In Jianzhong Jingguo Xudenglu 建中靖國續燈錄 [Continued Jianzhong Jingguo Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 7, p. 680c. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Mengxiang 閆孟祥. 2006. Preface. In Songdai Linji Chan Fazhan Yanbian 宋代臨濟禪發展演變 [The Evolution of Linji Zen in the Song Dynasty]. Beijing: China Religious Culture Publisher, vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagida, Seizan 柳田聖山. 1978. “Shinzoku toshi no keifu”,“新続灯史の系譜: 叙の一”. Zenga ku Kenkyū 禪學研究 59: 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Ji 虞集. 2007. Dayuan Guangzhi Quanwu Da Chanshi Taizhong Dafu Zhu Dalongxiang Si Shijiao Zongzhu Jianling Wushan Si Xiaoyin Sugong Xingdao Ji 大元廣智全悟大禪師、太中大夫、住大龍翔集慶寺、釋教宗主,兼領五山寺笑隱訴公行道記 [Biography of the Great Zen Master Dayuan Guangzhi Quanwu, Senator, Abbot of Dalongxiang Jiqing Temple, Patriarch of Buddhism, and Head of Wushan Temple, Xiaoyin]. In Yuji Quanji 虞集全集 [The Complete Works of Yu Ji]. Translated by Ting Wang 王頲. Tianjin: Tianjin Press for Classic Books, vol. 2, pp. 1046–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Mengfu 趙孟頫, and Weijiang Qian 錢偉彊. 2012. Beiming 碑銘 [Epitaph]. In Zhao Mengfu Ji 趙孟頫集 [Zhao Mengfu’s Collected Works]. Zhejiang Wencong 浙江文丛 [Zhejiang Literature Series]; Hangzhou: Zhejiang Ancient Books Publishing House, vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhengshou正受. 1975a. Ershisi Zhijuan Shiyi Weixiang Fasi Zhe 二十四之卷·拾遺(未詳法嗣者) [Volume 24—The Remains (Unspecified Inheritance Disciple)]. In Jiaputai Denglu Zongmulu 嘉泰普燈錄總目錄 [Catalogue of Jiaputai Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 24, p. 284c. [Google Scholar]

- Zhengshou正受. 1975b. Jiangshan Zanyuan Chanshi Fasi Erren 蔣山贊元禪師法嗣二人 [Two Inheritance Disciples of Jiangshan Zanyuan Zen Master]. In Jiaputai Denglu Zongmulu 嘉泰普燈錄總目錄 [Catalogue of Jiaputai Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 1, p. 317c. [Google Scholar]

- Zhengshou正受. 1975c. Jiantingfu Kaishan Mu’an Daoqiong Shouzuo 建寧府開善木庵道瓊首座 [First Seat Daoqiong at Kaishan Mu’an of Jiangning Fu]. In Jiaputai Denglu Zongmulu 嘉泰普燈錄總目錄 [Catalogue of Jiaputai Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 79, p. 366a. [Google Scholar]

- Zhengshou正受. 1975d. Longxing Fu Jiuxian Qifu Chanshi 隆興府九仙齊輔禪師 [Jiuxian Qifu, the Zen Master in Longxing Prefecture]. In Jiaputai Denglu Zongmulu 嘉泰普燈錄總目錄 [Catalogue of Jiaputai Lamp History]. Edited by Kōshō Kawamura 河村孝照, Giyū Nishi 西義雄 and Kōshirō Tamaki 玉城康四郎. Shinsan Dai Nippon Zokuzōkyō 卍新纂大日本續藏經. Tokyo: Kokusho Kankōkai, vol. 7, p. 334c. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, Ze 宗賾, and Yang Liu 劉洋, eds. 2020. Regulation for Abbot 尊宿住持條 [Zunsu Zhuchi Tiao]. In Chan Garden Regulations 禪苑清規 [Chanyuan Qinggui]. Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Hao 鄒浩. 2004. Xu Qing Chanshi Yulu Xu 序·慶禪師語錄敘 [Preface—Narrative of Zen Master Qing’s Discourses]. In Daoxiang Xiansheng Zouzhonggong Ji 道鄉先生鄒忠公集 [Daoxiang Mr. Zou Zhonggong’s Collection]. Beijing: Xianzhuang Shuju, vol. 28, p. 214. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ge, Z.; Guo, Y. Spatio-Temporal Process of the Linji School of Chan Buddhism in the 10th and 11th Centuries. Religions 2023, 14, 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101334

Ge Z, Guo Y. Spatio-Temporal Process of the Linji School of Chan Buddhism in the 10th and 11th Centuries. Religions. 2023; 14(10):1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101334

Chicago/Turabian StyleGe, Zhouzi, and Yongqin Guo. 2023. "Spatio-Temporal Process of the Linji School of Chan Buddhism in the 10th and 11th Centuries" Religions 14, no. 10: 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101334

APA StyleGe, Z., & Guo, Y. (2023). Spatio-Temporal Process of the Linji School of Chan Buddhism in the 10th and 11th Centuries. Religions, 14(10), 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14101334