A Transatlantic Tale of Monsters and Virgins: Our Lady of Sorrows and the Crocodile

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Our Lady of Sorrows and the Crocodile

It is told of a gentleman from Icod, who, while crossing a river in Mexico, was attacked by a terrible caiman and, seeing himself in great danger, invoked the holy image, miraculously saving himself from the sharp teeth of the amphibian, being lucky enough to stick his sword through its huge mouth and pierce its heart, leaving it instantly dead. As it had killed many people and animals, they decided to give it to the Virgen de las Angustias, for which purpose it was skinned and stuffed, sent to said shrine, where it has been hanging from the roof for years for honor and glory of the most holy image.

Because of the greater worship and devotion of the said Holy Image, honor and glory of God our Lord and spiritual good of all the faithful, I begged His Illustrious Lordship, the bishop of these islands, Don Juan Francisco Guillén, grant me his blessing and license to erect and construct at my expense a shrine on my estate, which they call El Molino Nuevo (The New Mill), which is at the low and extreme of this island, to place the said Holy Image there, and so that the faithful and poor who, due to their scarcity, would have a remedy there, so as not to be left without attending the Holy Sacrifice of the mass.(AHPT: PN 2575, ff. 284v-28519)

3. The Material Turn

3.1. A Fierceful Exvoto

Is there a material memory of past actions? Is it possible to trace the remnants of artistic practices, of knowledge and feelings in the entrails of the material? An image is effective when its materiality not only accompanies its meaning, but also when it builds it, defines it, creates it. It is about a mental and material density that should not be underestimated when investigating any object and that it is impossible to avoid if we want to understand the creative processes, the production and consumption conditions or the functions that some fulfilled in the society that housed them.

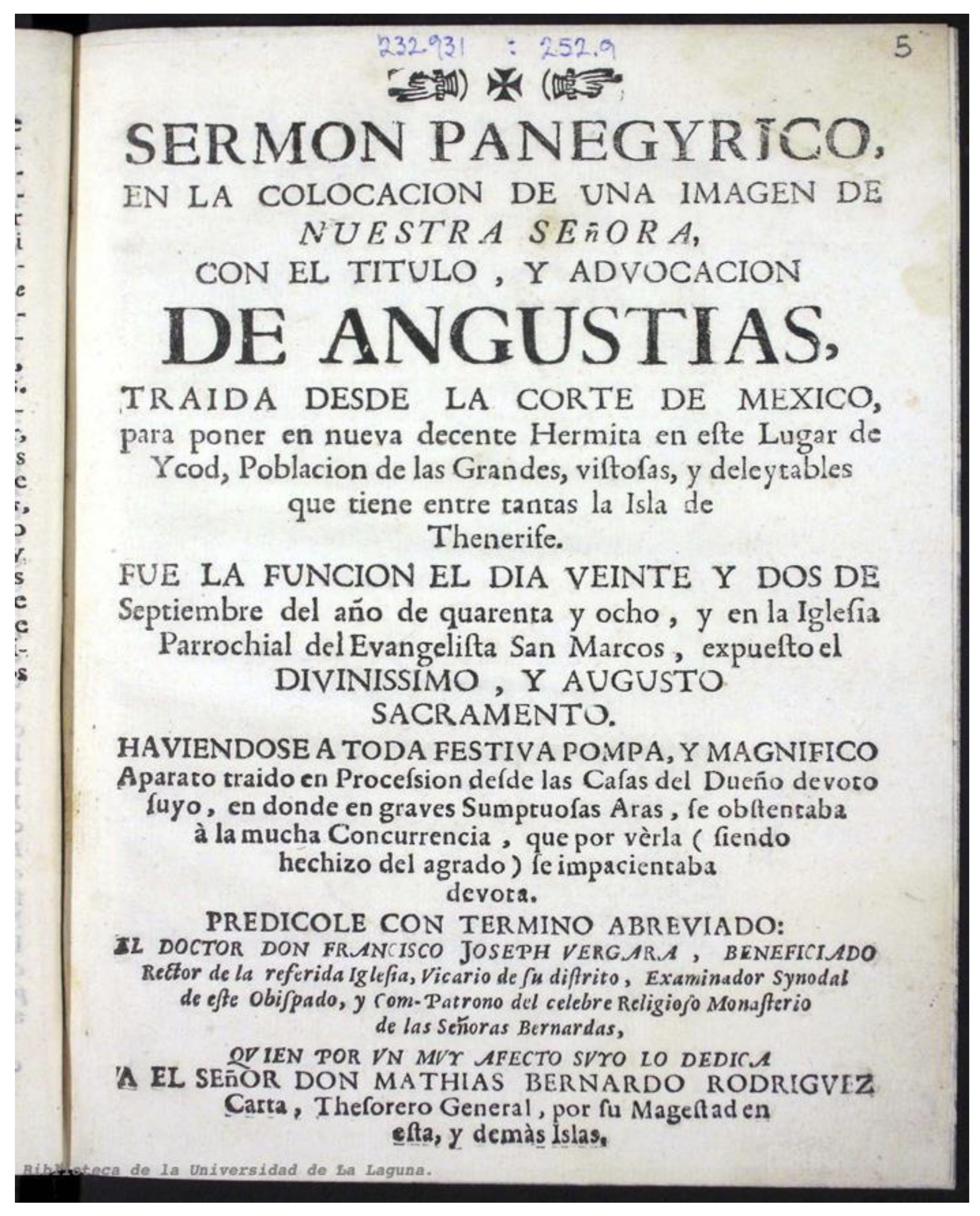

3.2. The “Sermón Panegírico:” A Hierofany of Sorrows

she is a pilgrim because she is beautiful and also because she is a stranger … she is such a pilgrim that she has no mansion of her own. Stand today, oh Catholic gathering, venerable crowd, that lively ark, sacrifice of guilt, as our advocate, enter, I mean to say, through your Temple and its doors the Pilgrim, that you see, if she is pretty and also a stranger, since coming from so far traveling sea and land, she appears as a stranger, still crying this joy, if today she asks us for hospitality.

[of the] common adversary [the Devil] [so] that you do not come here [to Tenerife] (which is to oppose the joys, which come to us from his anxieties) to Thou he made so much war and against Thou was his cunning. Against this astonishment of elegance or disdain of beauty for the true Image of Angustias, then draw [you] the devotees the consequence of these adventures and see why this Queen has gone through sorrows, anxieties, and perils to make us happy.

[The first danger was that she] fell into a river, which quickly carried her away. If it had not been for the very hand of her devoted owner who followed her and saved her. The second was the battle, in which the ship is seized by enemy hands and our Virgin becomes a prisoner: but she frees herself… and the third danger was the sudden fire in the vessel, with flames already emerging out of the edges and the rigging, it was forced to ruin, shipwrecked among the waves. But tricks [of the Devil] are mocked, this Queen takes wings of protection to help smother the fire, without being intimidated to appease any: and from here the wind in the stern would reach our Beaches, the ship being received with the welcome and applause that no other has received until now, not so much because of its increased interest but, Señora, because Thou arrived, you encouraged Faith for such a demonstration … And we don’t know up to now that any other image of MARIA with the title of Angustias has gone through as much as the one that is in sight.

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | See Carmagnani’s (2012) study on the trade of non-European luxury goods in Europe from the 17th to the 19th centuries, especially American and Asian luxury products that impacted the most in the Old World (tea from China, sugar, tobacco, and coffee from America and Asia). For this critic, the very concept of “luxury” is fluid. In it intervened moral, religious, economic, social, and political elements (2012, p. 20). First consumed by the elite, and then amidst a complex market, these products started to become available to the middle and lower classes, moving from luxury to general consumer goods. He proposed that goods consumption, including luxury items, must be recognized as a dynamic factor of not only economic growth, but also of power and political relationships between nations (2012, p. 33). The circulation of luxury goods set not only new commercial routes, markets, and needs, but also an incipient globalization and mundialization. Consequently, the impact of sumptuary goods changed social and even class dynamics in Europe and modified the interaction among economic, social, institutional, and cultural dimensions in old markets. I would add that the religious dimension was also altered by newly imported sacred goods, and the Indianos, a group of people, mostly merchants of Hispanic origin from the Canary Islands who, once enriched, chose to return to their homeland, would be a decisive factor of change and agency, as we see in my case study. |

| 2 | On other images and sculptures of American origin found in the Canary Islands, see Domingo Martínez de la Peña (1997) who made a complete catalogue of the paintings and sculptures ordered by Indianos and, such as Marcos Torres’ Virgin, brought back by them in their last and final voyage home, as a testimony of trade and relationships among the New World and the archipelago. Martínez de la Peña stated that not all images are of the same quality or beauty, depending on the workshop and workmanship. Most images are bulk images of crucified Christs, advocations of the Virgin as Rosary, Sorrows, and also saints as Saint Francis of Assisi, Saint Jude Thaddeus, etc. |

| 3 | “[C]onstituyen un buen exponente a la hora de calibrar la circulación de modelos foráneos y, de una u otra forma, confirman el carácter aperturista de sus puertos durante largo tiempo”. All original quotes will be placed in footnotes. All translations, if not indicated otherwise, are from the translator of this article. |

| 4 | On the Indigenous slave trade and the enslavement of Indigenous peoples to the Canary Islands, see (van Deusen 2015). |

| 5 | The transatlantic route known as the “Carrera de Indias” was a very dangerous one. Added to the difficulties of the sea travel were the storms, the precarious conditions of the trip, the scarcity of food and comforts on board, war conflicts, the time it took to cross the Atlantic, and the pirates and bandits that constantly threatened the ships and their precious cargoes. The pirates represented one of the most serious problems of maritime security, as can be seen from the numerous references that appear in the correspondence and documents of the time, denouncing theft of material goods and various merchandise, and harassment of sacred images at the hands of the English: “infidels and enemies of our kingdom, who so diminish the interests that we all have” [“infieles y enemigos de nuestro reino, que tanto merman los intereses que todos tenemos”] (quoted in (Lorenzo Lima 2018, p. 15)). On the Carrera de Indias, see (García-Baquero González 1992). |

| 6 | “De ahí que ese siglo constituya un período de esplendor para la contratación de plata, pintura y efigies remitidas por lo general desde Nueva España, Guatemala, Venezuela y las islas del Caribe”. |

| 7 | “y el afán por dejar un recuerdo de sus hazañas en la tierra natal propiciaron que llegaran a las Islas un notable conjunto de bienes americanos, pudiendo considerar al Archipiélago como la región española que atesora un mayor volumen y variedad de piezas”. |

| 8 | “hacer fortuna en relativamente poco tiempo y regresar con ella, y por ello se deja a la mujer o a los familiares más queridos. El mito del Indiano como el emigrante que regresa con una sólida riqueza para proporcionar bienestar a su familia y a su pueblo es el más extendido”. |

| 9 | The case of Our Lady of Candelmas is paradigmatic thanks to the round trip she endeavours. It is an invocation typical of the archipelago that travels one way to the Andes, where, due to the performance of some local “miracles”, her cult gains strength, becomes miraculous, broadnened the circle of her devotees among criollos and native Americans, and returned to the Canary Islands almost in a new fashion, in the form of an image of American origin, and with a reputation for working wonders. As we see, the journey is not unidirectional. The dynamics of the return trip affect both sides of the Atlantic. (see, among others, Salles Reese 2008; Cumming 2004; Montes González 2014; Díaz and Stratton-Pruitt 2014). On the round-trip travels of certain transatlantic devotions, see (Favrot Peterson 2014). |

| 10 | Marcos de Torres wrote the opening text that accompanies the sermon offered at the enshrinement of the Virgin in the hermitage of Icod. It is a well-organized and well-written text, with references to the authorities of the Church and didascalies. |

| 11 | In 1747 he began preparing his information on quality of nobility, the first step for the concretion of his primogeniture. |

| 12 | Most of the goods imported for what later become the Icod de los Vinos hermitage that housed Our Lady of Sorrows came from these places. For example, we know that the silver lamps came from Cuba, the ring that would be used by the Mexican image of the Virgin come from Campeche, and the diadem and silver dagger were brought from Guatemala (Amador Marrero 2021). |

| 13 | In the Spanish world, both in the peninsula, the archipelago, and also the colonies, Marian devotions turned to be of great importance. There were not only the establishment of new cults and devotions in the Indies (Guadalupe, Rosary, Mercedes, Copacabana, Sorrows, etc.), but also transatlantic movements of great interest, as the Virgin of Candelmas mentioned before. Marian cults evolved and changed over the centuries, and they are being keep alive in Spanish America. The analysis of the deep rooting of Marian cults exceeded the scope of this article, but it was well studied by (Christian 2012; Favrot Peterson 2014; Taylor 2016), who study specifically the advocation of Our Lady of Sorrows in New Spain (see p. 252 and passim) and (Zinni 2023) among others. |

| 14 | “Cuéntase de un caballero de Icod, que al pasar un río en Méjico [sic], fue atacado por un terrible caimán y como se viera en recio peligro, invocó a la santa imagen, salvándose milagrosamente de los afilados dientes del anfibio, teniendo la suerte de meterle su espada por la descomunal boca y atravesarle el corazón, dejándole instantáneamente muerto. Como había hecho muertes en personas y animales, decidieron regalárselo a la Virgen de las Angustias, a cuyo fin fue desollado y relleno, enviado a dicha ermita, donde hace años yace pendiente de la techumbre para honor y gloria de la santísima imagen”. The crocodile, from the Tabasco area of the Gulf of Mexico, has undergone some restorations that have conservation issues and bad decisions. These animals were not generally treated with highly regarded taxidermy techniques due to the rush to move them, which resulted in marked deterioration not only as a consequence of the transatlantic voyage, but also due to the environmental conditions in which they were exposed throughout the centuries. The body has been painted green to highlight its color, the jaws red, and the teeth white, in addition to replacing parts that have been lost over the years. It is currently in a glass case next to the image of Our Lady of Sorrows. |

| 15 | “para los que no han visto den grasias al Criador de la monstruosidad que produsen aquellos caudalosos Ríos, con su constansia que este es Cría respecto haverlos tan grandes y feroses que causan espanto como acreditan quantos ha pisado aquella jurisdision”. |

| 16 | This kind of story, which we will see later, is quite common in traveling images, which overcome difficulties, point out places where they want to see their sanctuary built, or decide to “stay” in a particular place. |

| 17 | “había tenido la gloria de traer consigo de la Corte de México Reyno de la Nueva España la imagen de mi Madre y Señora con el título de Angustias que por mi devoción mandé esculpir en aquella corte”. |

| 18 | “especial Protectora la mas afligida Reyna, Virgen, y Madre de un Dios, con atributo de Angustias, que en recintos de la Mansion que aquí tengo, mis anhelos colocaron, cumpliéndose mis desseos”. |

| 19 | “Su mayor culto y debosion de dicha Santa Ymagen honra y gloria de Dios nuestro Señor y bien espiritual de todos los fieles suplique a Su Señoría Ylustrísima el Señor obispo de estas yslas Don Juan Francisco Guillén me consediese su bendision y lisensia para erigir y fabricar a mis expensas una ermita en mi hasienda que llaman el molino nuebo que es bajo y estremo de este lugar para colocar en ella dicha Santa ymagen y que los fieles y pobres que por su cortedad tuviesen allí remedio a no quedarse sin oyr el Santo Sacrifisio de la misa”. |

| 20 | “haviendose a toda festiva pompa, y magnifico aparato traído en Procession desde las Casas del Dueño devoto suyo, en donde en graves sumptuosas aras, se obstentaba a la mucha Concurrencia, que por verla (siendo hechizo del agrado) se impacientaba devota”. |

| 21 | Marcos Torres cultivated a deep relationship with Matías Bernardo Rodríguez de Cata, treasurer of the king. The latter introduced Torres into commercial venues where he became one of the most important local credit agents, along with his own brother, Domingo de Torres. |

| 22 | “Hallome bien alcanzado de su benevolo genio, no poco favorecido de su natural agrado; de dia en dia … en todos los lanzes lo atento: y en fin, siempre existente el favor, sin siquiera resfriarlo aún las Ondas y avenidas de transmarinas distancias, a muchos años de ausencia”. |

| 23 | A comprehensive bibliography on the displacement of goods and peoples, as well as the incipient globalization movements and trades, exceeded this article. Among others, see (Tracy 1990; Martínez and Melgar 2005; Gruzinski 2006, 2010; Mignolo 2000; Carmagnani 2012; Hausberger 2019). For an introduction to Pacific trade, see (Ardash Bonialian 2012). |

| 24 | “la memoria visible y silenciosa de lo que ocurrió entre las sociedades europeas y las otras partes del mundo”. |

| 25 | On crocodiles in European Catholic sanctuaries, see Amador Marrero and Díaz Cayero (2023), who follow Padrino Barrera, Domenech, and various online sources in their analysis of this particular animal. It is not my intention to study the crocodile as it is in a liturgical space, but rather as the companion of Our Lady of Sorrows in her sanctuary of Icod de los Vinos. |

| 26 | “¿existe una memoria material de las acciones del pasado? ¿Es posible rastrear las huellas de prácticas artísticas, de conocimientos y sentimientos en las entrañas de la materia? Una imagen tiene eficacia cuando su materialidad no solo acompaña su sentido, sino también cuando lo construye, lo define, lo crea. Se trata de un espesor mental y material que no debería ser subestimado a la hora de investigar cualquier objeto y que es imposible evitar si queremos comprender sus procesos creativos, sus condiciones de producción y consumo o las funciones que alguna cumplió en la sociedad que la albergó”. |

| 27 | “en un presente familiar, en una señal de afecto, o en un instrumento de prestigio con vocación diplomática”. |

| 28 | “pasa por una serie de metamorfosis en que se leen los efectos y las etapas de la intervención europea”. |

| 29 | Not all Indianos make a fortune and not all trips obtain good results. Many times, the merchandise is lost, and with it, money and capital, so it is advisable to thank the sacred beings who made the journey possible. See Hernández González (1991) for an analysis of the relationship between trade and emigration in the Canary Islands and Gramatke (2020) for a study of the difficulties of moving statues and other sacred images overseas. |

| 30 | The original title reads: “Sermón Panergírico en la colocación de una imagen de Nuestra Señora, con el título y advocación de Angustias, traída desde la corte de Mexico, para poner en nueva decente Hermita en este Lugar de Icod, Población de las Grandes, vistosas y deleytables que tiene entre tantas la Isla de Thenerife”. |

| 31 | “alusiones a su propia condición de ‘imágenes’ y al prestigio de su origen. Asimismo, motivó que se crearan numerosas leyendas acerca de su fabricación y de su percepción, y que hubiera una destacada producción escrita sobre la imagen religiosa”. |

| 32 | “Esa dimensión cultural o devocional hace que en torno a las imágenes sagradas (individual o colectivamente) se forme una compleja casuística que las sitúa en un campo más allá de la pura representación”. |

| 33 | “Vino a nosotros aquella Santa Imagen desde el centro de la plata, otro como nuevo mundo, que es la Mexicana Corte: aquí la devoción se la apropria … porque así, o Gran Señora, seas como ya se ve, que eres aquella insigne Muger que de remotas distancias traen tus prendas el aprecio”. |

| 34 | “los propios lugares de origen de los objetos que circulan”. |

| 35 | “cómo poner en primer plano un sentido de distancia en la historia que construimos alrededor de algunos objetos, [que] nos permite ver y entender mejor la conciencia del lugar del propietario y/o espectador”. |

| 36 | “peregrina por hermosa y también por forastera … tan peregrina se halla que no tiene mansión propia … Colocasse oy, o Catholico Congresso, Venerables atenciones, aquella animada Arca, propiciación de las culpas, si es Abogada nuestra, entrasse, quiero decir, por vuestro Templo, y sus puertas la Peregrina, que veis, si lo es por agraciada, y también por forastera, pues viniendo de tan lexos transitando mar, y tierra, se aparece como estraña, aun llorando esta ventura, si oy nos pide posada”. |

| 37 | “los Rios no ahogaron tus anhelos por venirte hacia nosotros”. |

| 38 | “sucediendo en uno muchos milagros, que es nadie entre tantos maltratarse, y caer a vuestro lado los globos, o las encendidas balas”. |

| 39 | “[del] adversario común [para] que no vengas aquí (que es oponerse a las dichas, que nos vienen de sus ansias) a Vos hizo tanta guerra y contra Vos fue su astucia. Contra ese pasmo de gala o desdén de la belleza por vera Imagen de Angustias, pues saque la devoción consecuencia de estos lances, y vea por qué penas, por qué ansias y fatigas esta Reyna no ha pasado a fin de hacernos dichosos”. |

| 40 | Amador Marrero (2021); Amador Marrero and Díaz Cayero (2023), among others, studied in depth Ripa’s allegory of America. |

| 41 | “Soberanos pasos! Lanzes prodigiosos! Todos son ansias, pero felices: todo fatiga, pero gloriosa: en fin Angustias, pero dichosas. O como, Fieles, aquí debierais exhalar el alma toda en ternura, admirando la venida de esta Imagen Prodigiosa! Admirando quando se opuso el Demonio porque llegara a nosotros aquel Soberano hechizo”. |

| 42 | “Fue lo primero sumergirla en un Rio, que rápido la llevara. No ser por la prompria [propia] mano del devoto dueño suyo que la sigue y acompaña. Lo segundo la batalla, que estimula, para que el Vagel se apresse, y de aquí venga a manos enemigas, y passe a nuestras Aras: pero ella misma se libra … Y lo tercero fue prenderse de improvisso un fuego en el Vagel, que saliendo ya por el borde y por las Jarcias en llamas, era forzossa la ruina, naufragando entre las ondas: pero se burla la astucia, tomando alas de protección esta Reyna, para acudir a el ahogo, sin que acobarde para aplacarlo ninguno: y de aquí viento en popa aportar a nuestras Playas, siendo el Vagel recibido con el gusto y el aplauso que ninguno hasta ahora, no tanto por su cresido interés, si empero, Señora, porque arribabais Vos, que estimulasteis la Fe para tal demonstración … Luego sino sabemos hasta ahora, que otra imagen de MARIA con el Titulo de Angustias haya pasado por tantas que es la que está a la vista”. |

| 43 | “ya tenéis mansión propia … passeés en hora buena a vuestra propia Possada”. |

| 44 | The Philippine Islands will be a fundamental issue in this type of analysis, but that is beyond the scope of this study. |

| 45 | “peregrina por hermosa y también por forastera”. |

| 46 | Martínez de la Peña (1997) states that most of the images that crossed the Atlantic during the 16th and 17th centuries came from Mexico, while some others arrived from Cuba, which accounts for the Indiano trade route. |

| 47 | One example of the displacement of center/periphery vectors occurred, as Gruzinski pointed out, with the creation of a regular maritime route with Philippines and Japan, wherein Mexican inhabitants used to say they lived “in the heart of the world” (2006, p. 225). |

References

Documents

Archivo Histórico Provincial de Santa Cruz de Tenerife PN2608. Ante Juan José Soperanis Montesdeoca. San Cristóbal de La Laguna.Archivo Histórico Provincial de Santa Cruz de Tenerife PN2757. Ante Pedro Alfonso López. San Cristóbal de La Laguna.Sitas de Tributo de D. Marcos de Torres y Marqués de Fuentes y Palmas. Colección particular. San Cristóbal de La Laguna.Printed Sources

- Alcalá, Luisa Elena. 2021. El concepto de distancia en el estudio del arte virreinal. Latin American and Latinxs Visual Culture 3: 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador Marrero, Pablo F. 2009. Candelaria Indiana. Devoción y veras efigies en América. In Vestida de Sol. Iconografía y Memoria de Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria. Edited by Carlos Rodríguez Morales. Tenerife: Caja Canarias Obra Social y Cultural. [Google Scholar]

- Amador Marrero, Pablo F. 2012. De Oaxaca a Canarias: Devociones y “traiciones”. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 34: 39–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador Marrero, Pablo F. 2018. El legado Indiano en las Islas de la Fortuna. Escultura Hispanoamericana en Canarias. México: Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas—UNAM. [Google Scholar]

- Amador Marrero, Pablo F. 2021. Las obras desde su materialidad: Impronta indiana. In Tornaviaje. Arte Iberoamericano en España. Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, pp. 103–27. [Google Scholar]

- . Amador Marrero, Pablo, and Patricia Díaz Cayero. 2023. El pellejo del dragón: Cocodrilos y caimanes, exvotos para la Reina del Cielo. In Animalística. XXXVIII Coloquio Internacional de Historia del Arte. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, pp. 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ardash Bonialian, Mariano. 2012. El Pacífico Hispanoamericano: Política y Comercio en el Imperio Español (1680–1784). México: El Colegio de México. [Google Scholar]

- Arribas y Sánchez, Cipriano de. 1993. A Través de las Islas Canarias. Santa Cruz: Museo Arqueológico, Aula de Cultura del Cabildo de Tenerife. [Google Scholar]

- Carmagnani, Marcello. 2012. Las Islas del Lujo. Productos Exóticos, Nuevos Consumos y Cultura Económica Europea, 1650–800. México and Madrid: El Colegio de México/Marcial Pons. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, William A., Jr. 2012. Divine Presence in Spain and Western Europe 1500–960. New York: Central European University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran-Tad, Noa, Jorge Ulloa Hung, Andrzej T. Antczak, Eduardo Herrera Malatesta, and Corinne L. Hofman. 2021. Indigenous Routes and Resource Materialities in the Early Spanish Colonial World: Comparative Archaeological Approaches. Latin American Antiquity 32: 468–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, Thomas. 2004. Painting of a Statue of the Virgin of Candelmas. In The Colonial Andes. Tapestries and Silverwork, 1530–1830. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 265–66. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, Josef, and Suzanne Stratton-Pruitt. 2014. Painting the Divine. Images of Mary in the New World. Santa Fe: The New Mexico History Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Favrot Peterson, Jeanette. 2014. Visualizing Guadalupe. From Black Madonna to Queen of the Americas. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- García-Baquero González, Antonio. 1992. La Carrera de Indias. Suma de la Contratación y Océano de Negocios. Sevilla: Algaida. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Luis-Ravelo, Juan. 2022. Investigaciones Sobre Arte, Cultura y Patrimonio. In De la historia de la Semana Santa de Ycod. Los Legados de Escultura Americana en el siglo XVIII, Aportación Devocional de los Indianos. Edited by Pablo Hernández Abreu. Icod de los Vinos: Ayuntamiento de Icod de los Vinos, pp. 223–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gramatke, Corinna. 2020. ‘Llegó en malísimo estado la estatua de San Luis Gonzaga.’ La dificultosa organización del envío de obras de arte en los siglos XVII y XVIII desde Europa a las instituciones jesuíticas de las Américas. In Tornaviaje. Tránsito Artístico Entre los Virreinatos Americanos y la Metrópolis. Santiago de Compostela: E.R.A. Arte, Creación y Patrimonio Iberoamericano en Redes, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, pp. 149–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gruzinski, Serge. 2006. Mundialización, globalización y mestizaje en la Monarquía católica. In Europa, América y el Mundo: Tiempos Históricos. Madrid: Marcial Pons, pp. 217–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gruzinski, Serge. 2010. Las Cuatro Partes del Mundo. Historia de una Mundialización. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Hausberger, Bernd. 2019. Historia Mínima de la Globalización Temprana. México: El Colegio de México. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández González, Manuel. 1991. El mito del indiano y su influencia sobre la sociedad canaria del siglo XVIII. Tebeto IV: 47–71. [Google Scholar]

- Keehnen, Floris W. M., Corinne L. Hofman, and Angrezej t. Antezak. 2019. Material Encounters and Indigenous Transformations in Early colonial Americas. Introduction. In Material Encounters and Indigenous Transformations in Early Colonial Americas. Archaelogiccal Case Studies. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo Lima, Juan Alejandro. 2008. De escultura colonial y comercio artístico durante el siglo XVIII. Nuevas consideraciones sobre la imaginería americana en Canarias. Encrucijada, 38–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo Lima, Juan Alejandro. 2018. Arte y comercio a finales de la época moderna. Notas para un estudio de la cultura sevillana en Canarias (1770–1800). Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos 64: 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mariscal, George. 2001. The Figure of the Indiano in Early Modern Spanish Culture. Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies 2: 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez de la Peña, Domingo. 1997. Esculturas americanas en Canarias. En Francisco Morales Padrón (coord.). In Actas del II Coloquio de Historia Canario-Americana. Gran Canaria: Cabildo de Gran Canaria, vol. II, pp. 475–93. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Shaw, and Carlos y José María Oliva Melgar, eds. 2005. El sistema atlántico español (siglos XVII–XIX). Madrid: Marcial Pons. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, Walter. 2000. Local Histories/Global Designs. Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montes González, Francisco. 2014. Vírgenes viajeras, altares de papel: Traslaciones pictóricas de advocaciones peninsulares en el arte virreinal. In Arte y patrimonio en España y América. Montevideo: Universidad de la República, pp. 89–117. [Google Scholar]

- Padrino Barrera, José Manuel. 2013. Los exvotos en Tenerife. Vestigios materiales como expresión de lo prodigioso. I. Revista de Historia Canaria 195: 47–78. [Google Scholar]

- Padrino Barrera, José Manuel. 2016. Los exvotos en Tenerife. Vestigios materiales como expresión de lo prodigioso. III. Revista de Historia Canaria 198: 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Portús, Javier. 2016. Metapintura: Un Viaje a la Idea del Arte en España. Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Méndez, María de las Nieves. 2019. Un viaje de cinco mil Millas. España: Editorial Círculo Rojo. [Google Scholar]

- Salles Reese, Verónica. 2008. De Viracocha a la Virgen de Copacabana. Representación de lo sagrado en el lago Titicaca. La Paz: Plural. [Google Scholar]

- Simerka, Barbara. 1995. The indiano as liminal figure in the drama of Tirso and his contemporaries. Bulletin of the Comediantes 47: 311–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siracusano, Gabriela, and Agustina Rodríguez Romero. 2017. Materiality between Art, Science and Culture in the Viceroyalties (16th–17th Centuries): An Interdisciplinary Vision towards the Writing of a New Colonial Art History. In Art in Translation. Edimburgo: University of Edimburgh, vol. 9, pp. 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Siracusano, Gabriela, and Agustina Rodríguez Romero, eds. 2020. Materia Americana. El Cuerpo de las Imágenes Hispanoamericanas (Siglos XVI a Mediados del XIX). Buenos Aires: Editorial de la Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, William B. 2016. Theater of Thousand Wonders: A History of Miraculous Images and Shrines in New Spain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, James D., ed. 1990. The Rise of Merchant Empires. Long-Distance Trade in the Early Modern World, 1350–1750. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Deusen, Nancy. 2015. Global Indios. The Indigenous Struggle for Justice in Sixteenth-Century Spain. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vergara, Francisco José. 1751. Sermon panegírico en la colocación de una imagen de Nuestra Señora, con el título y advocación de Angustias, traída desde la corte de Mexico, para poner en nueva decente Hermita en este Lugar de Ycod, Población de las Grandes, vistosas y deleytables que tiene entre tantas la Isla de Thenerife. [Google Scholar]

- Zinni, Mariana. 2023. “Statuary Painting in Colonial Andes: ‘Indian’ Virgins and Resacralization of the Religious Landscape”. In Polychromy in the Early Modern World: 1200–800. New York: Routledge Publishers, pp. 128–49. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zinni, M. A Transatlantic Tale of Monsters and Virgins: Our Lady of Sorrows and the Crocodile. Religions 2023, 14, 1385. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14111385

Zinni M. A Transatlantic Tale of Monsters and Virgins: Our Lady of Sorrows and the Crocodile. Religions. 2023; 14(11):1385. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14111385

Chicago/Turabian StyleZinni, Mariana. 2023. "A Transatlantic Tale of Monsters and Virgins: Our Lady of Sorrows and the Crocodile" Religions 14, no. 11: 1385. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14111385

APA StyleZinni, M. (2023). A Transatlantic Tale of Monsters and Virgins: Our Lady of Sorrows and the Crocodile. Religions, 14(11), 1385. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14111385