1. Introduction

The wedding ceremony is a socially recognized ritual that marks the establishment of a marital bond between a man and a woman. It encompasses the entire process from proposal to engagement to the actual wedding ceremony itself (

Ma 2014). Etiquette and ceremonial rites are integral aspects of Chinese life (

Peng et al. 2022). In ancient China, the wedding ceremony was also referred to as the “hun li (昏禮)” and was one of the “jia (嘉)” ceremonies (

Hu 2019). It served as a means of assisting a newlywed couple in transitioning into their new roles and identities, representing the beginning of a new family. Particularly for women, marriage is the means for obtaining a permanent place to belong and become a part of the husband’s family. Ancient Chinese wedding ceremonies, rooted in Confucianism, held strong ethical and social significance under the guidance of Confucian ideology. These rituals played a crucial role in educating society and regulating behavior. Confucianism emphasized the responsibilities and obligations of parents, asserting that couples should strive together to procreate and pass down their values, thereby perpetuating their lineage and family ideals. Therefore, despite variations across different historical periods, ancient Chinese wedding ceremonies consistently emphasized the stability of marriage and the importance of the family, advocating for mutual respect, care, and support between spouses.

Many religions have specific wedding rituals that are established based on religious beliefs and doctrines, and China is no exception. Some scholars consider Confucianism to be a religion, while others argue that it is better classified as a philosophy, moral system, or cultural tradition (

Cahill 2001). However, it is evident that Confucianism emphasizes personal cultivation, ethical morality, family values, and social order, and its teachings and values hold significant religious and spiritual significance for many Chinese individuals. Confucianism plays a central role in shaping the ideological framework. It emphasizes that human actions should align with “virtue” and establishes a set of norms based on moral requirements known as “rituals”. The formulation, regulation, and value concepts of ancient Chinese weddings, in particular, stemmed from Confucianism, and their development occurred within the core framework of Confucianism while being influenced by societal, cultural, artistic, and economic changes of the time. The earliest records of Chinese weddings can be found in the Confucian classic,

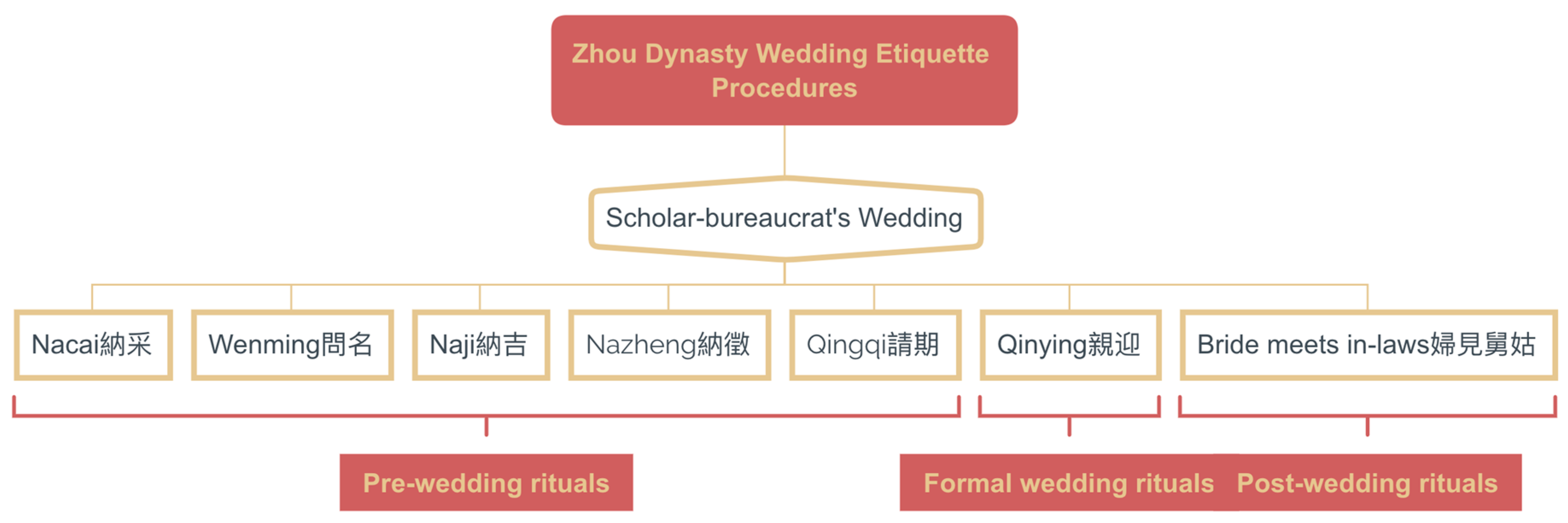

Yi Li · Shi Hun Li 儀禮·士昏禮, from the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods (770–221 BCE), which outlines the main procedures of the wedding ceremony as the “Six Rites”. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to primarily explore the developmental trends of the Six Rites in later periods, aiming to investigate the interaction between Confucian ideology and ancient Chinese wedding ceremonies and their influence.

Currently, research on ancient Chinese traditional wedding ceremonies can be classified into three main categories. The first category focuses on exploring wedding customs and rituals from the standpoint of pre-Qin ceremonial systems and Confucian classical texts. Yang Zhigang conducted a comprehensive study on the various forms of wedding ceremonies within the overall framework of Chinese ritual systems (

Yang 2001). Chang Jincang systematically categorized ancient Chinese discussions on rituals, thereby elucidating the distinct boundaries of wedding ceremonies and customs within the scholarly domain (

Chang 2005). Chen Shuguo and Lan Jiayun provide a detailed examination of wedding rituals from ancient times to the pre-Qin period (771–221 BCE) based on the

Zhou Yi 周易, with particular reference to polygamous marriages with concubines following the marriage (

Chen and Lan 2007). Xu Wei and Xu Huimin focused their research on the wedding ceremonies depicted in the Book of Rites, providing insights into the metaphysical foundations, value, significance, and potential limitations of ancient Chinese wedding rituals (

Xu and Xu 2016). Meng Qingnan summarized the early Confucian perspectives on the significance of wedding ceremonies, highlighting the themes of harmonious bonding and mutual respect (

Meng 2017).

The second category involves a systematic study of wedding ceremonies as part of marriage from the perspective of ancient Chinese marital history. Some comprehensive works in this category include Chen Guyuan’s extensive discussion on the historical development of Chinese marriage, specifically addressing the characteristics of wedding ceremonies in the section on marriage methods (

Chen 1987). Wang Binling analyzed various wedding rituals and marital customs of different ethnic groups in China from the perspective of marital history (

Wang 2013). Chen Peng focused on the process of marriage formation, emphasizing different forms of marriage that existed in Chinese history and organizing historical materials related to wedding rituals and customs (

Chen 2005). Furthermore, there are specialized studies on wedding ceremonies and customs during specific dynasties. For instance, Peng Liyun explored the wedding system and distinctive features of the Song Dynasty (960–1279) (

Peng 1988), while Xie Baofu conducted a detailed investigation into wedding rituals and phenomena during the Northern Dynasties (386–589) (

Xie 1998). Qu Ming’an used the study of wedding ceremonies in a particular dynasty to explore the main characteristics of royal weddings throughout history. By focusing on the discourse and ritual elements in the process of courtship and marriage in the scholar–bureaucrat’s wedding during the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE), Qu Ming’an proposed the significant viewpoint that ancient Chinese royal weddings formed a symbol system with a binary structure (

Qu 2020).

The third category involves interdisciplinary research on wedding ceremonies from a socio-cultural perspective. Chen Xiaofang used the

Annals of Spring and Autumn 春秋左傳 as a blueprint and proposed the theory of “Three Rituals for Spring and Autumn Weddings” (

Chen 2000). Lu Shiqiu, from a comparative religious studies perspective, vividly presented the prevalent folk wedding and funeral customs in China through a combination of text and illustrations (

Lu 2009). Zheng Huisheng attempted to discuss the relationship between the status of women in pre-Qin society and marriage from a female perspective and explored research in the field of cultural linguistics, revealing the implicit relationship between ancient Chinese kinship terms and wedding systems (

Zheng 1988). Ji Guoxiu linked wedding ceremonies with social structures and the evolution of the ceremony with social change, analyzing the changes in Chinese village weddings within the context of social networks (

Ji 2005). Additionally, numerous scholars have compared and summarized the cultural customs of wedding ceremonies in different regions or among different ethnic groups in China. For example, Xu Yuan and others discovered wedding custom activities in the Hanzhong region (

Xu et al. 2014), and Wan Delengzhi and Zheng Dui explored the changes in traditional wedding customs of the Tibetan ethnic group (

Wan and Zheng 2020). These studies reflect the influence and development of traditional wedding ceremonies and concepts in various regions, broadening the research perspective on ancient Chinese wedding ceremonies.

As an interdisciplinary research topic, ancient Chinese weddings have been widely studied in terms of their constituent factors and influences. Currently, there are abundant research results on ancient weddings influenced by Confucianism, which provide important insights into the inheritance and transformation of wedding rituals. However, most of them focus on macro-level discussions of the history of marriage or specific studies of a single dynasty or region. There is a lack of research on how the Six Rites in the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE) impacted and permeated later wedding ceremonies, as well as the evolution of wedding rituals throughout different dynasties under the influence of Confucianism.

Therefore, this study primarily centers on the Confucian wedding rituals of the Chinese elite, exploring the successive wedding rituals formulated by rulers and the phenomenon of wedding activities dominated by the scholarly class as the entry point. The focus is on the examination of the ritual processes and customs of ancient weddings, as well as the contextual design and underlying conceptual ideas. This leads to the following research questions: How did the Six Rites, established based on Confucian ideology, change, adapt, and transform over time? How did the designers of wedding ceremonies and political-economic factors influence the dimensions of the ritual performances? Is there any interaction and influence between the practices of wedding ceremonies and Confucian norms and values? In the scope of research on ancient Chinese weddings, the state rituals and folk customs are inseparable. Under the guidance of ritual systems as ideological guidelines, the differences between eras also contribute to the distinctive folk performances of wedding ceremonies. In response to the research question, we analyzed the wedding rituals and customs of major dynasties. Two main historical lines were summarized. Firstly, the ancient Chinese wedding rituals were developed and evolved from the foundational Six Rites proposed by Confucianism, represented by Confucius during the pre-Qin period. Secondly, the wedding customs in ancient China experienced a transition from Confucianism-dominated Han culture to a fusion of diverse cultures and ideologies. Ultimately, it critically advocated the pre-Qin Confucian ideology represented by Confucius to guide and explore the past and future of Chinese Confucian weddings.

2. Methodology

This study employs historical research and literature analysis methods. A comprehensive review and analysis of existing literature shows that the formulation, norms, and value systems of ancient Chinese weddings are rooted in Confucian wedding rituals. However, previous research has predominantly focused on specific dynasties or regional wedding customs, lacking an exploration from the perspective of historical evolution and succession regarding the development of ancient Chinese wedding ceremonies under the influence of Confucian thought. Furthermore, there is a notable absence of holistic comparative analyses across different centuries. Historical research is a methodology that employs historical records to study past events in chronological order. In China, these transitions are marked by dynastic changes, defining distinct periods of social life. Consequently, this study explores the evolution of ancient Chinese wedding ceremonies across various historical periods, focusing on key dynasties that underwent significant transformations and developments for in-depth investigation.

This study collected primary source materials and used a systematic literature research method to analysis and explore the ancient Chinese wedding ceremony. The study used the Confucian classic text “Yi Li·Shi Hun Li 儀禮·士昏禮” as a model to investigate the six rites in ancient China. This text provides a comprehensive record of the wedding ceremonies during the Zhou Dynasty and is one of the earliest and most complete classical works documenting these rituals. It has also served as an authoritative reference for subsequent studies of wedding rituals. Therefore, the third section of this study thoroughly examined the core rituals, processes, and concepts of Confucian wedding ceremonies during the Zhou Dynasty.

Based on this foundation, the study delved into two specific aspects of ancient Chinese wedding ceremonies: the official and the folk traditions. On the official level, historical accounts and records of royal and aristocratic weddings were mainly derived from official ritual classics. In the Song Dynasty, private literary works such as “Jia Li 家禮” provided further insights into ceremonial customs. This study collected relevant literary materials spanning from the Han Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty and, in combination with ancient court paintings, explored significant changes in wedding rituals during different dynasties. A comparative analysis was conducted, comparing them with the ‘Six Rites’ documented in the Confucian classic “Yi Li·Shi Hun Li 儀禮·士昏禮”, examining their characteristics, evolution, and connection with Confucian cultural thought. On the folk level, customs and traditions of ancient Chinese weddings gradually formed in local communities, often without official historical records. The data in this research area were mainly sourced from historical records, local gazetteers, novels, poetry, and Dunhuang manuscripts, as well as visual evidence from murals and artifacts. Descriptions of wedding scenes were commonly found in everyday life records, oral histories, folk songs, and documents describing geographical landscapes. These materials effectively depicted wedding scenes from various dynasties. Therefore, representative texts related to Confucian cultural thought and enduring wedding customs were selected as focal points. They were systematically summarized and organized, effectively reconstructing the visual representations of wedding customs and activities from different dynasties. In summary, the comprehensive application of these two methods enables a thorough and holistic study of the historical, cultural, and religious background of ancient Chinese weddings under the influence of Confucian thought. This approach also sheds light on the status and impact of weddings in traditional Chinese society.

Nevertheless, there are certain limitations in this study. Firstly, Confucianism itself is not inherently religious, yet it holds significant religious and cultural value in ancient Chinese society. There is an interrelation between ancient Chinese weddings and religious studies, potentially influenced by various religious wedding rituals. While this paper discusses the introduction of Christian weddings during the Republican era, leading to the emergence of modern civil weddings, it lacks a more detailed examination of these connections. Our study aims to reveal the historical evolution of wedding ceremonies, but further exploration is needed to unravel the intricate relationship between Confucianism, religion, and ancient Chinese wedding rituals.

Secondly, the study of Confucian wedding rituals demands more refined methodologies when considering the complexity and changes spanning different historical periods. By employing phenomenological analysis, more intricate and subtle questions can be posed. Given the profound and extensive nature of ancient Chinese wedding customs, it is challenging to provide a comprehensive and objective assessment with only a few centuries of research. This paper represents an initial exploration, opening the door for further research into Confucian wedding rituals, which still provides ample opportunities for scholarly exploration.

4. The Evolution of Ancient Chinese Wedding Rituals: Transition from Ritualization to Secularization Based on the Six Rites

The order of ancient Chinese wedding ceremonies went through a development process from the establishment during the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE) to the reform during the Qin and Han Dynasties (221 BCE–220 CE), the gradual integration of folk customs during the Tang and Song Dynasties (618–1279), and the ultimate introduction of ethnic culture during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912). In the Zhou Dynasty, noble families practiced polygamous marriages, and marriage was a significant matter for maintaining the lineage. According to the description in

Zuo Zhuan·Wen Gong Er Nian 左傳·文公二年, “When a monarch ascends the throne, he should establish good relations with neighboring countries and secure marriage alliances. He should marry a primary wife to preside over sacrifices, which is in line with filial piety. Filial piety is the beginning of propriet” (

Zhu 2008). It can be seen that marriage was also a way for the state to strengthen alliances through marriage alliances during the pre-Qin period (

Cao 2000). The relationship between weddings and religion can be observed on various levels, with some connections being more apparent than others (

Höpflinger and Mäder 2018). Religious beliefs influence the specific content of wedding ceremonies, prompting us to explore the mutual impact between religious beliefs and wedding rituals at the level of the ceremony.

Confucian wedding rituals embody the concept of harmony between heaven and humanity, playing a significant role in upholding and perpetuating traditional values such as marriage, family stability, and filial piety. The motives and values underlying wedding ceremonies throughout different historical periods are largely consistent with those of the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE), primarily aimed at establishing alliances between two families, solidifying family influence, ancestral worship, and procreation. Scholars such as Zhai Ming’an believe that the basic paradigm of royal weddings in ancient China, especially of the Han ethnic group, comes from the wedding ceremonies of the aristocrats in the Zhou Dynasty. The royal weddings established by other ethnic groups that formed their own regimes each have their own regional and ethnic characteristics (

Qu 2020). Subsequently, during the Tang and Song Dynasties (618–1279), the “Six Rites” were simplified and merged, while during the Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368–1912), some ritual procedures were abolished. This demonstrates that the content and procedures of wedding ceremonies throughout history have slightly increased or decreased due to changes in the times and differences in the social hierarchy while preserving certain traditional elements.

4.1. From “Not Celebrating” to “Celebrating Weddings”

During the Qin and Han Dynasties (221 BCE–220 CE), most weddings strictly adhered to the Six Rites system of the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE). However, significant reforms occurred in the ancient Chinese marriage system during this time. The Han Dynasty’s wedding ceremony replaced the Zhou Dynasty’s ceremony, which did not include a congratulatory procedure. At the same time, the trend of extravagant weddings began. During this period, political factors played a dominant role in wedding ceremonies, particularly during the flourishing of Confucianism in the Han Dynasty. The prevailing wedding customs led by the Han rulers vividly demonstrated how political power could influence and regulate marriage.

During the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), the collection and organization of Confucian classics were basically completed, and they were canonized through the dominance of Confucianism. As a result, the life etiquette of the Han Dynasty followed the ancient system, as recorded in the

Book of Han 漢書: “due to the agreement on wedding and funeral ceremonies, it was slightly in accordance with the ancient etiquette and not allowed to deviate from the law” (

Ban 1962). In addition, the wedding congratulatory tradition first appeared in the Han Dynasty and has continued in later generations. During the Western Han period (206 BCE–9CE), Emperor Xuan of Han (73–49 BCE) issued an edict stating, “The rites of marriage are the most important in human relationships. Banquets and feasts are held to practice ritual and music. Now, some officials in the counties and states, in their arbitrary enforcement of harsh laws, prohibit the people from holding wedding banquets and feasts. This abolishes the customs of the clans and deprives the people of their joy, which does not lead them” (

Ban 1962). This was the first time in Chinese history that wedding celebrations were affirmed through legislation, which changed the Zhou Dynasty’s etiquette of not using music or celebrations in weddings and emphasized the importance of banquets and feasts in conducting rituals and music (

Du 1988).

During the Qin and Han dynasties (221 BCE–220 CE), the types and quantities of betrothal gifts increased significantly compared to the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE). According to the

Tong Dian 通典, there was a total of 30 items, each with its auspicious symbolism, including cases of ink, Lu cloth, sheep, geese, clear wine, white wine, deer, and flint (

Du 1988). Finally, the Confucianists advocated establishing a state religion that mirrored the laws of heaven and earth in terms of time, clothing, and ceremony. Therefore, during the Zhou Dynasty, wedding attire primarily featured the colors “xuan (玄)” and “xun (纁),” which symbolized the colors of heaven and earth. In the pre-Qin period (771–221 BCE), wedding attire tended to be simple, but with the appearance of wedding congratulatory decrees, Han Dynasty wedding attire began to evolve in the direction of luxury and splendor. The

Hou Han Shu·Yu Fu Zhi 後漢書·輿服誌 records that “princesses, noblewomen, and concubines above the rank of consort may wear twelve-colored heavy-edged robes made of brocade, silk, gauze, grain silk, and silk gauze on their wedding day” (

Sima 1965). From the changes in wedding attire, we can see that weddings during this period began to exhibit hierarchical characteristics among the imperial family and aristocracy. Therefore, political and economic factors in the Han Dynasty exerted a significant influence on the performance dimensions of wedding ceremonies, such as banquet arrangements, ceremonial music, and attire. These factors impacted the design, scale, extravagance, social expectations, and hierarchical distinctions associated with the wedding rituals.

4.2. From “Six Rites” to “Three Rites”

During the Tang and Song dynasties (618–1279), influenced by the “Revival Movement of Ancient Rites,” Confucianism was highly respected during that time period (

Wu and Wang 2022). Therefore, the rulers of the Tang Dynasty (618–907) continued to use the “Six Rites” in the weddings of the royal nobility but changed the system and “abolished the system of ‘rituals not for the common people’ (禮不下庶人)

8”. In the Song dynasty (960–1279), the same rituals were adopted by both the scholar–officials and the commoners (

Yang 1993). The gentry mainly used simplified “Three Rites of Nacai (納采), Nabi (納幣), and Qinying (親迎)”, which signaled a significant departure from the six rituals of the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE). As a result, wedding ceremonies began to shift towards secularization.

During the Tang dynasty (618–907), strict regulations were imposed on wedding ceremonies, emphasizing the significance of rituals and music and the addition of ceremonies such as the coronation ceremony and the Shao Lao ceremony (少牢禮). Records of wedding rituals during the Tang dynasty mainly focus on imperial weddings found in works such as Kaiyuan Li 開元禮, Tongdian 通典, Xinshu 新書, and Tang Huiyao 唐會要. In the imperial wedding ceremonies, the first five rituals were consistent with the customs. However, there were three notable differences compared to the Six Rites. First, the status of the male family’s representative was elevated, with the Grand Commandant serving as the envoy. Second, synchronized music performances were included, highlighting the importance of ritual and music. Third, during the stage of the bride’s welcoming, the emperor did not personally greet the bride but delegated an envoy to receive her. Additionally, the first recorded princess wedding ceremony in the Tang Dynasty included the addition of the coronation ceremony and the Shaolao ceremony, which were noble ceremonial activities with sheep as sacrifices, and the omission of the ceremony of “taking the breast meat and giving it to mother-in-law.”

The emergence of Cheng-Zhu Neo-Confucianism

9 during the Song dynasty (960–1279) propelled Confucian thought to new heights, leading to significant changes in wedding ceremonies during this period. Song dynasty weddings became more secularized, and for the first time, specific wedding rites were formulated for the gentry, simplifying the rituals from the traditional Six Rites to the Three Rites commonly observed among the scholar–official class (

Yang 1993).

At the aristocratic level, the wedding ceremonies of the Song dynasty’s imperial family closely resembled the general outline described in ancient ritual texts. However, several additions were made to the existing Six Rites. These included the presentation of the Six Rites book before the formal betrothal, the reception of the bride with the attendance of court officials, and the ceremonial ringing of bells and drums. Princess weddings also involved additional processes, such as providing the emperor’s son-in-law with clothing, wealth, and a noble residence, highlighting the elaborate and costly nature of Song dynasty imperial weddings. Subsequently, at the commoner level, the Song dynasty introduced the compilation of wedding rituals for the scholar–official class in the official ceremonial book,

Zhenghe Wuli Xin Yi 政和五禮新儀. The rituals combined the processes of betrothal inquiries and formal engagement, simplifying the gift requirements. For instance, the San She Sheng (三舍生)

10 ceremony allowed the use of sheep in-stead of live geese, as traditionally required in the Six Rites. Commoners were permitted to substitute wild or domestic chickens as gifts.

In addition to the aforementioned developments, the literati of the Northern and Southern Song dynasties (960–1279) (

Yang 2010), in their efforts to counterbalance Buddhism and Daoism, created a system of rituals that harmonized state ceremonial laws with popular customs, leading to the Confucianization of wedding practices in society. Sima Guang, during the Northern Song period (960–1127), provided a detailed account of folk wedding procedures in his work. The specific sequence of the “Qinying Ceremony” comprised six steps: paying respect to the ancestral tablet, ritual purification, reciprocal salutations, sharing sacrificial food, pouring and drinking wine, and exchanging cups. Zhu Xi, in his work from the Southern Song period (1127–1279), simplified the six rituals into three: “Nacai (納采)” (betrothal inquiries), “Nabi (納幣)” (presenting betrothal gifts), and “Qinying (親迎)” (receiving the bride). According to the regulations, the host was required to present the marriage contract in the ancestral hall during the Nacai ceremony, while the Nabi ceremony involved the presentation and reception of documents and ceremonial etiquette. The Qinying ceremony emphasized the supplementary ritual of the host making an announcement in the ancestral hall. The first procedure of the Qinying ceremony took place in the early morning when both families set up ancestral tablets and ancestral plaques, performing the ritual of offering sacrifices to inform the ancestors of the marriage, signifying respect for the ancestral lineage. Furthermore, the “sharing sacrificial food (同牢之禮)” ritual was replaced with the groom’s offering of wine and the bride’s offering of a cup, followed by pouring a cup without offering food, and then three cups were used for the ceremonial toast. In Confucian thought, ancestor worship and witchcraft coexisted. Therefore, the introduction of these rituals during the Song dynasty further reinforced Confucian values and emphasized the consolidation of gender roles and social responsibilities.

Since the establishment of the “Three Rites” wedding format, the influence of “Jia Li 家禮” on the marriage rituals of the scholar–official class during the Song and Yuan dynasties (960–1368), as well as the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368–1912), has been profound, leading to increased attention to the wedding ceremonies of the scholar–official class. The transition from the “Six Rites” to the “Three Rites” can be seen as a reflection of how wedding ceremonies symbolize changes in social structure, cultural norms, and perspectives on life. The evolution of state-sanctioned wedding rituals also gradually adapted to the needs and realities of the general populace.

4.3. From “Han System” to “Manchu-Han Syncretism”

During the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368–1912), wedding rituals and ceremonies were organized in a hierarchical manner. In the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), weddings at various levels, particularly imperial weddings, were primarily based on the established Six Rites that had been passed down through generations. During the “Qinying” stage, the “sharing sacrificial food” ritual was merged with the pouring and drinking of wine, as well as the exchange of cups. In the Qing dynasty (1644–1912), while incorporating Ming dynasty systems, the customs and regulations of Manchu culture were also introduced, resulting in a diverse and inclusive characteristic.

During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), the system of Six Rites was reinstated, and there was a strict hierarchy in wedding rituals at different levels. According to the

Ming Shi·Li Zhi Jiu 禮志九·明史, wedding ceremonies could be classified into six categories: the emperor’s marriage ceremony, the wedding of the Crown Prince, weddings of imperial princes, weddings of princesses, weddings of high-ranking officials, and weddings of commoners. Even when the Ming emperors took consorts, they still adhered to the Six Rites system. Similar to the Tang dynasty (618–907), during the “Qinying” stage, the emperor would be represented by appointed officials to receive the bride. The wedding ceremonies of crown princes and imperial princes followed a similar pattern, with the Six Rites as the main framework, emphasizing that the groom personally welcomed the bride during the “Qinying” stage. In the wedding ceremonies of princesses, the rituals per-formed by the bridegroom’s family were similar to those of the imperial family. The difference lay in the “Qinying” stage, where, before the ceremonial toast, the bridegroom would perform four ceremonial bows to show respect to the princess (

Yi 2017). The wedding ceremonies of high-ranking officials, known as “Pin Guan”

11, placed a greater emphasis on post-marriage etiquette. It was required that on the second day, the groom, along with his father, and the bride, along with her mother, would offer incense and make offerings of wine at the ancestral temple. Afterward, the bride would pay respects to her parents-in-law and perform the ritual of washing their hands and presenting food, with the bride serving the parents-in-law. Additionally, according to the

Ming Hui Dian 明會典, during the “Qinying” stage of the wedding ceremonies of Ming emperors and high-ranking officials, the “sharing sacrificial food” ritual was combined with the subsequent “Zhen Ji (振祭)” ritual, which held an equivalent status to the ancient rituals. There was no separate “sharing sacrificial food” ritual. The “Zhen Ji” ritual involved inserting the sacrificial offerings into soy sauce or salt, shaking them to remove excess grains, and then proceeding with the ceremony. After the ritual was complete, the offerings would be tasted (

Shen 1989). The records in the

Ming Shi 明史 regarding the wedding ceremonies of commoners are relatively simple. The overall ceremonial procedures are similar to those of high-ranking officials, especially in terms of modifying and restoring the three rites prescribed in Zhu Xi’s

Jia Li 家禮 from the Song dynasty (960–1279) to the Six Rites. Additionally, in the Ming dynasty commoners’ wedding ceremonies, there was flexibility to accommodate secular needs. On the wedding day, the attire and accessories could exceed their own social class. The groom would wear the official robe of the ninth rank. This practice also demonstrated the significance attached to this ritual, aligning with the concept of “Dressing beyond the usual class for a wedding, extraordinary” (

Zheng 2021) in Zhou dynasty wedding ceremonies.

Despite the frequent changes in political power in China, the country’s cultural form has remained largely intact (

Peng et al. 2022). During the establishment of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912), there was a continuation of the Six Rites system inherited from previous dynasties, along with the integration of distinct Manchu influences. The most notable change in Qing dynasty wedding rituals was the incorporation of Ming dynasty practices, combined with the addition of Manchu cultural customs. The fusion of these elements resulted in a diverse and inclusive wedding system that incorporated various aspects, including the ceremony process. The

Qing Shi Gao 清史稿 provides detailed accounts of the wedding rituals and protocols for different social classes, including the emperor, crown princes, princesses, and high-ranking officials (

Tong 1991). For instance, the illustration in

Figure 3 of the “Complete Pictorial of Wedding Ceremonies” during the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1875–1908) depicts a grand procession for the bride’s welcoming, with imperial envoys sent on behalf of the emperor. Additionally, it was required that one day before the wedding, officials be sent to perform sacrificial rituals at the suburban altar and ancestral temple. In addition to the traditional and standardized Six Rites, there are additional steps specific to the imperial princes’ weddings. The prince and his bride must observe a nine-day post-wedding period known as “Gui Ning (歸寧)” before returning to their residence. In the case of princesses’ marriages, the Qing dynasty incorporated its own customs. After the marriage is arranged, the groom must go through a ritual similar to betrothal inquiries at the Meridian Gate. On the wedding day, it is strictly required for the groom’s family to pay respects at the Meridian Gate and present specific gifts known as the “Yi Jiu (一九)” ceremony, which includes a precise number of items such as 18 saddled horses, 18 sets of armor, 21 horses, 6 mules, 81 sheep, 45 bottles of milk wine and yellow wine, and 90 banquet tables. Finally, the princess must return to the palace and express gratitude after a nine-day post-wedding period. Therefore, in Qing Dynasty weddings, there was a significant association with political values. These ceremonies and regulations, which accommodated both Manchu and Han traditions, may have symbolized the endorsement and support of the Qing government.

During the Qing dynasty (1644–1912), it was stipulated that the marriage rituals for the scholar–official class should follow the Nine Ranks of the Official Ceremonial System. There were significant changes in wedding ceremonies for both the scholar and com-moner classes compared to the traditional Six Rites. One notable change was the inclusion of the “Ji (笄)” ceremony

13 in the “Qinying” stage, which took place on the wedding day after the bride’s family made ancestral offerings. Additionally, according to the

Pingyang Fu Zhi 平阳府志, “wedding ceremonies varied in different regions, but generally only four of the Six Rites remained: ‘Wenming’, ‘Nacai’, ‘Qingqi’, and ‘Qinying’, although in some cases the bride’s arrival may not occur” (

Linfen Cultural Bureau 2018). This indicates the possibility of simplifying the ceremonies to include only the four rituals of asking for the name, betrothal inquiries, setting the wedding date, and the bride’s arrival. Therefore, the Qing government-imposed restrictions and regulations on the requirements and procedures of marriage ceremonies through the establishment of laws and regulations. In addition to following the Six Rites, weddings across different social classes in the Qing Dynasty were also influenced by Manchu wedding customs, such as the “Yi Jiu (一九)ceremony,” “Jiu Ri Gui Ning (九日歸寧),” “Hun ri Ji Li (婚日笄禮),” and “San Gui Jiu Kow (三跪九叩禮)”. This also reflects how political power can influence the performance dimension of rituals through the promotion and shaping of the marriage system in order to achieve specific political objectives or propagate the values of Manchu culture in the Qing Dynasty.

5. From Han Culture to Multicultural Integration: The Evolution of Ancient Chinese Wedding Customs

There exists a significant correlation between ritual behaviors and specific secular social relationships (

Geertz 1993). Since ancient times, weddings have been inseparable from both “rituals” and “customs”. Rituals serve as social norms, while customs are the default rules that emerge from habitual practices (

Hu 2019). Wedding customs refer to the actual forms of wedding ceremonies that people have historically practiced. They represent the accumulated conventions and habits that have developed over long periods of societal life, which official orthodoxy cannot overlook (

Sun 2020). Some scholars argue that wedding customs serve as a supplement to formal wedding ceremonies, and thus, the study of weddings should not disregard these customs (

Hu 2019). The customs and practices of ancient Chinese wedding ceremonies gradually developed within the context of folk social life. In this subsection, we focus on selecting relevant and representative texts related to Confucian cultural thought and enduring wedding customs, summarizing and organizing them, and conducting in-depth research. It can be observed that throughout different dynasties, rulers have played a significant role in shaping the design, scale, and extravagance of rituals, which in turn influenced the formulation of wedding ceremonies by the general public. However, on the other hand, folk customs often deviate from ritual propriety, thereby challenging the ethical norms and hierarchical order imposed by the rulers. Therefore, there exists a conflicting and harmonizing relationship between wedding customs and the formalized wedding ceremony system.

Although the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) continued the tradition of the Six Rites, the concept of social status became prominent with the improvement of material wealth. The practice of “marriage based on wealth” emerged during the Han Dynasty (

Huo 2018). This change reflects the evolving cultural norms of social etiquette. Since the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE–9 CE), as a result of reforms in the marriage system, tranquil and simple wedding ceremonies were replaced by lively and extravagant ones. Especially during the Eastern Han period (25–220), Cai Yong’s

Xie He Hun Fu 協和婚賦 and the

Book of Han·Geographical Records 漢書·地理誌 depicted numerous festive scenes of wedding celebrations featuring customs such as veiling the bride’s face with a scarf (jinsha zhe mian)

14 and throwing a canopy (sa zhang)

15. These customs were introduced to enhance the festive atmosphere of the wedding procession. It can be said that there is a corresponding relationship between wedding customs and rituals, and these customs have continued into later generations. In summary, the Confucian-advocated wedding rituals were primarily intended for the upper class, especially the “Li bu xia shu ren (禮不下庶人)” concept, which emphasized the distinction between the elite and the common people. Consequently, ordinary citizens were not eligible to follow strict ceremonial practices, leading to a lack of adherence to Confucian wedding customs in folk traditions. Folk wedding practices typically embody rich cultural traditions and values. These practices reflect the specific cultural context’s understanding and importance of marriage and family. Therefore, we will examine, from the perspective of folk wedding activities characterized by significant temporal changes, the social, political, cultural, and economic norms and values expressed in religious wedding practices.

5.1. Wedding Customs Blending Northern Ethnic Minority Traditions

With ethnic integration during the Tang Dynasty (618–907), a large number of northern ethnic minorities migrated to the Central Plains region, cohabiting with the Han Chinese and gradually assimilating into the local culture. Interethnic marriages became common, and as a result, the wedding customs of the northern ethnic minorities directly influenced the wedding customs of the Central Plains ethnic groups (

Shen 2012). In the Tang Dynasty, a trend emerged of blending folk wedding customs with those of the northern ethnic minorities. Scenes depicting wedding ceremonies among the common people during the Tang Dynasty can be found in Dunhuang literature, mural depictions, and other sources. The

Hun Shi Cheng Shi 婚事程式 documented the inclusion of customs such as Cui zhuang (applying the bride’s makeup), Zhang che (blocking the carriage), and Cui hua Que shan (presenting flowers and fan-waving) in the wedding rituals of ordinary people during the Tang Dynasty. Additionally, the “

Youyang Zazu 酉陽雜俎” also recorded changes in the wedding procession, shifting from dusk to early morning, and the wedding chamber venue transformed into a “Qing lu,” also known as the “Hundred Sons Canopy (百子帳),” a tent-like structure made of green cloth (see

Figure 4), resembling the domed dwellings of northern ethnic minorities, and incorporating customs such as Nong xu, Hejin (合卺), and Heji (合髻) (

Duan 1987).

It is evident that ethnic integration profoundly influenced the evolution of Tang Dynasty weddings, with folk customs being particularly prominent and prevalent. One of these customs is known as cui zhuang, which refers to the moment when the bride is received, and the groom’s family leads a group of a hundred or several dozen people who collectively call out, “The bride emerges,” until the bride reaches the carriage. The practice of applying makeup originated between the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–589). In the

Dongjing Menghua Lu 東京夢華錄 (a description of the works of Bianliang, the capital of the Northern Song Dynasty), it is recorded that the purpose of applying makeup is similar to an invitation (

Meng 2019). Another custom is called zhang che, which refers to the practice of neighbors and relatives intercepting the wedding carriage during the marriage procession. The groom’s side must offer gifts, food, and beverages to be allowed to pass. Originally, this custom was intended to bid farewell to the bride but later transformed into a desire for food, money, and entertainment. The custom of cui hua que shan occurs after the ceremonial greetings. The bride’s floral headdress and ceremonial attire- are removed, and through poetic verses, the bride is encouraged to remove the fan that conceals her face. The bride traditionally uses a fan to cover her face during the wedding, not only to preserve modesty but also to ward off evil spirits. During the groom’s procession to fetch the bride, a playful tradition called Nong xu takes place, where the groom is subjected to various pranks and teasing for amusement. The ritual of Hejin (合卺) involves the couple drinking from the same cup during the formal meeting. After drinking together, the cups would be placed in a certain arrangement to symbolize good fortune. Lastly, Heji (合髻) refers to the use of the couple’s hair as a symbol of their marital union on the wedding day. Before toasting with the exchange of cups, they would each cut a strand of their hair, which would be intertwined to signify their unity of purpose.

In conclusion, the emerging wedding customs in the Tang Dynasty deviated from the requirements of traditional ancient rituals, resulting in instances of “breaching etiquette”. This starkly exemplified the contradictory relationship between wedding customs and ceremonial expectations during the Tang Dynasty.

5.2. The Wedding Customs of Seeking Wealth and Expressing Respect

During the Song Dynasty (960–1279), wedding customs and practices also reflected the expression of economic norms and values. This encompassed aspects such as dowry, wedding expenses, property inheritance, and economic support. With the flourishing of Confucianism during the Song Dynasty, scholar–officials from both the Northern and Southern Song periods actively sought to establish a system of etiquette that harmonized national rituals with folk customs (

Yang 2010). Scholar–officials produced works on ritual studies such as

Shuyi 書儀,

Hunli 婚禮, and

Jiali 家禮 to describe the wedding ceremonies of both the elite and commoners. Additionally, numerous literary works, including

Dongjing Menghua Lu 東京夢華錄,

Taiping Guangji 太平廣記,

Mengliang Lu 夢梁錄, and

Shilin Guangji 事林廣記, summarized the folk wedding customs of the Song Dynasty (960–1279).

Represented by

Dongjing Menghua Lu 東京夢華錄, these works detailed twelve folk customs previously unseen in earlier periods, including “qitiezi” (posting the wed-ding notice), “xukoujiu” (exchanging ceremonial drinks), “guodalizhi” (performing formal ceremony), “qiyanzi” (raising the canopy), “lanmen” (blocking the door), “jiabutadi” (not touching the ground with feet), “kuaan” (crossing the saddle), “zuoxuzhang” (sitting under a virtual canopy), “huasheng cumian” (flower-wearing and face-concealing), “lishijiaomenhong” (guests compete for pieces of colored cloth), “xufujiaobai” (bride and groom’s mutual bow), and “qianjin” (holding the handkerchief together). Economic factors played a significant role in Song Dynasty weddings, reflecting both the social and economic structure and the economic capacity and status of individuals and families. Simultaneously, the development of the commodity economy in the Song Dynasty (960–1279) also caused marriage customs to be more inclined towards wealth based on the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE). However, Confucian scholars, such as Sima Guang, criticized this materialistic tendency, arguing that such behavior was unworthy of scholar–official marriages (

Sima 1985). Confucius himself advocated marriage on the basis of virtue rather than lintel and on the basis of character rather than nobility (

Zhang 2006). He also promoted frugality in rituals and ceremonies, emphasizing simplicity over extravagance.

Specifically, notable wedding customs that reflect these types of activities include “guodalizhi” (performing formal ceremonies), “qiyanzi” (raising the canopy), “lanmen” (blocking the door), and “lishijiaomenhong” (guests competing for pieces of colored cloth). “Guodalizhi” involves the exchange of clothing and utensils between the two families of the newlyweds. During the “qiyanzi” stage, when the bride is about to enter the sedan chair, the bride’s family must offer colored silk, lucky money, items, or food for her to board the sedan chair and proceed. “Lanmen” occurs when the bride arrives at the groom’s house, and guests and family members block the entrance to seek money, gifts, and red envelopes. “Lishijiaomenhong” refers to the act of hanging a torn piece of floral cloth on the door of the newlyweds’ room on the wedding day. After the groom enters the room, people eagerly grab the torn edges of the cloth, symbolizing their desire for good luck and fortune.

In fact, from the above-mentioned wedding customs, it is evident that wealth and material possessions also serve as symbolic representations to a certain extent. Confucianism emphasizes “respect (敬)” (

Wu et al. 2022). The exchange of wealth during the wedding ceremony is also used as a gesture of “respect” between the families of the bride and groom, as well as within the associated communities. The custom of “xufujiaobai” (bride and groom’s mutual bow) further expresses this sense of respect between the couple. This activity involves the bride and groom bowing to each other on the wedding day, as recorded in the

Sima Shi Shu Yi 司馬氏書儀 (Book of Rites by Sima Guang): “In ancient times, there was no custom of the bride and groom bowing to each other. It is only in the contemporary society that this practice began (

Sima 1985)”. This indicates that this custom officially started during the Song Dynasty (960–1279). In the Southern Song period (1127–1279), according to the

Mengliang Lu 夢梁錄 (Records of Dreams in Liangzhou), the ritual of mutual bowing became more elaborate, including the use of scales or machines to lift the bride’s veil. For example, female figurines found in the tomb of Hong Zicheng in Moyang County, Jiangxi Province, from the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279) were adorned with a narrow strip of cloth on their heads (

Gao 2001), confirming the tradition of lifting the bride’s veil during the Southern Song period (see

Figure 5).

In conclusion, it is evident that economic factors can also influence the performance dimensions of wedding ceremonies. It can be seen that despite the Song dynasty’s em-phasis on rituals and wealth in marriage, influenced by the style of the times and running counter to Confucianism, there were some wedding customs that still conformed to Confucian notions of respectful culture.

5.3. Wedding Customs That Embody the Compatibility of Manchu and Han Ethnic Cultures

According to historical records in the book

Ke Zuo Zhui Yu 客座贅語, it is evident that certain wedding customs popular during the Tang and Song Dynasties (618–1279), such as “nongxu,” “zhangche,” “qinglu,” and “queshan,” were abolished during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). However, practices such as “cui zhuang” and “kuaan” were retained (

Gu 2009). Consequently, the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) simplified numerous wedding customs from the Tang and Song Dynasties (618–1279) while simultaneously incorporating many Manchu cultural elements, inheriting Han ethnic wedding customs. Drawing on the

Manzhou Hunli Yijie 滿洲婚禮儀節 (Manchu Wedding Rituals and Etiquette) as a reference and various novels and notes such as

Hong Lou Meng 紅樓夢 (Dream of the Red Chamber),

Xiang Yan Jie Yi 鄉言解頤, these included “nijin tiezi” (golden clay wedding invitations), “baoping kuaan” (carrying a bottle while crossing the saddle), “he jin yong bei” (uniting the couple with shared cups), “he jin song ci” (reciting vows during the union), “zuo chuang” (sitting on the marriage bed), “xinlang shejian” (groom’s archery), “huimen huijiu” (returning to the bride’s family nine days after the wedding). Moreover, in the

Manzhou Hunli Yijie 滿洲婚禮儀節, the “six rituals” of “nacai” (betrothal gifts), “nazheng” (groom’s formal proposal), and “qingqi” (wedding date confirmation) were renamed as “xiading” (engagement), “xiacha” (tea presentation), and “tongshu” (letter of agreement), respectively. Additionally, new participants in the wedding ceremony emerged, such as the “xiniang” (bride’s attendant) responsible for caring for the bride and the “binxiang” (groom’s companion) accompanying the couple (

Suo 2002).

By incorporating various Manchu customs into the wedding culture, the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) not only preserved Han ethnic traditions but also introduced new wedding customs. These customs include the following: “Nijin Tiezi” refers to a practice where, after the engagement between the two families, the bride’s family writes a response letter on a marriage certificate using clay paint made from gold flakes and glue. “Baoping Kuaan” involves placing a saddle in front of the sedan chair when the bride descends from it. Carrying a porcelain vase, the bride steps over the saddle, symbolizing the wish for safety and well-being (

Pan 2013). “He Jin Yong Bei” and “He Jin Song Ci” refer to the Qing Dynasty practice where Manchu people recite specific vows during the Hejin ceremony. Specifically, it can be translated from classical Chinese as follows: “On this joyous day, the newlyweds enter into a harmonious union. Here, we bless this couple, hoping that they will live together in mutual respect and harmony”. In modern traditional Chinese weddings, this ritual continues to be preserved as an important element. Unlike the Ming Dynasty’s custom of combining the Tong Lao ceremony with toasting, which included three meals in the bridal chamber, the Qing Dynasty broke away from this tradition. Instead, elders would throw food on the roof of the chamber after each recitation, and the couple would use a pair of mandarin duck cups to symbolize their union (see

Figure 6). “Zuochuang” involves the bride entering a tent in the courtyard after the mutual bowing ceremony while the groom stands guard outside. The duration of the bride’s stay in the tent is flexible, depending on the weather. “Xinlang Shejian” refers to the groom shooting arrows towards the gate of the sedan chair after the bride arrives at the groom’s house. The bride can only descend from the sedan chair after three arrows have been shot. This custom also originates from Manchu traditions. “Huimen Huijiu” signifies the bride’s return to her family’s home after the wedding. “Huimen” refers to the three days after the wedding, while “Huijiu” refers to the nine days after the return.

In summary, Confucianism was not clearly evident in the folk wedding customs of the Qing Dynasty, while the trend of ethnic minority integration was increasingly strengthened. Furthermore, the inclusion of new rituals and activities contributed to the representation of the Manchu-Han ethnic symbol culture, serving as manifestations of encoding and rules within the cultural system of folk weddings in the Qing Dynasty.

5.4. Wedding Customs as a Result of the Collision of Chinese and Western Cultures

During the Republican era (1912–1949), Confucianism was no longer the mainstream ideology, and with the influx of Western culture, wedding customs became a blend of Chinese and Western elements, giving rise to a two-stage wedding ceremony. Traditional rituals and modern civilized weddings

17 coexisted and maintained their separate identities. Descriptions of wedding rituals and customs mostly came from local gazetteers and novels, with the Nanjing wedding depicted in the Jinling Magazine 金陵雜誌 as a typical example. It was found that traditional wedding ceremonies, which included the six rituals, preserved customs such as bed installation from the Tang Dynasty (618–907) and the ceremony of joining cups from the Song Dynasty (960–1279), albeit with different names. Additionally, new customs emerged, including the presentation of birth characters, the exchange of red invitations, the unveiling of the bride’s face, and the meeting of families, which changed the names of “requesting a date” and “proposing a marriage” to “sending the wedding date” and “seeking consent”, respectively (

Xu 2013). On the other hand, civilized weddings took place in venues such as assembly halls or large hotels and leaned more towards Western wedding customs overall.

The form and content of wedding ceremonies reflect social and cultural changes. Specifically, regarding traditional weddings, “sending birth characters” referred to the groom’s family sending a matchmaker to the bride’s family for the formal proposal. The bride’s family would write the birth characters on rough paper, commonly known as “grass invitations,” and send them to the groom’s family, exchanging birth character documents. If the compatibility were not suitable, they would be returned. This demonstrates that the Confucian doctrine of the Mean (中庸) has a significant influence on wedding customs, emphasizing harmony. Analyzing the compatibility through the Five Elements, Yin and Yang, and other factors is an essential aspect. “Exchanging red invitations” meant that after the engagement was confirmed through the eight-character match, the bride’s family would use golden clay paint to write the entire invitation card in red and send it to the groom’s family, who would reciprocate with various gifts. “Unveiling the bride’s face” took place on the morning of the day after the wedding, where the bridesmaid would serve lotus seed soup to the newlyweds and then help the bride with her makeup, symbolizing a change in hairstyle and facial decoration before the bride’s departure. “Meeting of families” refers to a banquet held by the groom’s family for the relatives of the bride’s family, aiming to strengthen the bond between the families. Therefore, even in traditional weddings, traces of the six rituals could still be observed, reflecting the importance of the Confucian principles of “respect” and “filial piety” in wedding morality during the pre-Qin period (771–221 BCE). In civilized weddings, the six ritual ceremonies were omitted. After obtaining the consent of both parents, the couple would exchange tokens and publish an engagement notice in the newspaper, solidifying the engagement. On the eve of the wedding date, a formal wedding notice would be published announcing the wedding date. On the wedding day, the ceremony would begin with the emcee, followed by the entrance of male and female guests, the main wedding couple and their families, the marriage witnesses, and the introducers, accompanied by music. The couple would then be led to their seats by the wedding attendant, and the marriage certificate would be read by the marriage witness. The witnesses, introducers, and the couple would then affix their seals accordingly. The couple would exchange rings, perform the bowing ceremony, express gratitude, and deliver speeches after receiving speeches or flowers from the guests. Finally, the newlyweds paid their respects to the officiants and relatives after the reception (

Yi 2017). This simplified wedding, modeled on the Western style, broke the framework of traditional wedding conditions and laid the foundation for the formation of the “modern new wedding”. The final stage of implementing marriage rituals among believers in Jiangnan is related to the 1911 Revolution, the ”New Culture” movement, and the promotion of “Transforming outmoded customs and habits (yi feng yisu 移風易俗)” by the government of the Republic of China (

Zhang 2023). Within society as a whole, the concept of marriage began to change.

The evidence suggests that during the Republican era (1912–1949), there was a departure from traditional Confucian wedding practices in China, leading to the emergence of modern weddings. This shift was driven by the influence of Western religious wedding ceremonies and concepts of marriage. As a result, modern Chinese weddings began incorporating elements such as ring exchanges and ceremonial rituals. This cultural exchange and adaptation sparked an innovative transformation in Chinese marital perspectives and wedding customs.

6. Conclusions

Ritual theory emphasizes the social functions and effects of rituals, specifically as meaningful roles, relationships, and systems that facilitate communication and foster social awareness (

Ames and Rosemont 1999). For instance, Emile Durkheim focuses on the relationship between rituals and social structure, emphasizing how rituals exert power in reality to integrate social resources, control social hierarchies, and reinforce social order (

Durkheim 2011). Meanwhile, Bell proposes a model of ritual consisting of three elements: ritual as an activity, the fusion of thought and activity, and the dichotomy between actor and thinker. She points out that in a constantly changing society, rituals serve as a bridge between tradition and ongoing social transformations (

Bell 1992). Rituals can also be employed to express judgments on the current society and aspirations for an ideal world (

Smith 1987). As a type of ritual, weddings can, therefore, strengthen the connections between individuals and society, establish the legitimacy and stability of marriages, and also provide social recognition and support. Under the influence of Confucianism, the wedding ceremony served as a sacred and solemn testament and union of marriage. At the national level, weddings were governed by the ritual system, and the Six Rites became the central benchmark for the wedding system of later generations. Throughout the dynasties, wedding rituals were developed based on the maintenance of the traditional Six Rites, gradually incorporating folk customs and becoming more secularized. The departure from the solemn and austere wedding practices during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), with the introduction of the celebratory wedding system, established a joyous and celebratory atmosphere for weddings. In the Tang and Song periods (618–1279), this festive spirit extended beyond the aristocracy and permeated the lives of commoners. However, for the average household, marriage remained a financially demanding endeavor. The simplified “Three Rites” better suited the economic capabilities and practical needs of the common people, leaving a profound impact on the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368–1912). During the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), various folk customs were incorporated, creating a distinct landscape that balanced the preservation of tradition with the accommodation of local practices.

The ritual system is the outcome of a gradual evolution from simplicity to complexity and from fragmented to systematic, rooted in the religious and daily lives of humans. Therefore, “ritual” and “custom” are inseparable and mutually influential. The phenomenon of wedding customs reflects, to a certain extent, the production and living conditions of the people during a certain period. Throughout different historical periods, the overall landscape of wedding customs has undergone a transition from Han Chinese cultural dominance towards the amalgamation of diverse cultures. Social context and ethnic heritage have consistently been the driving factors. Starting from the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), wedding ceremonies particularly emphasized the symbolic nature of wedding dowries. During the Tang Dynasty (618–907), wedding customs were influenced by the practices of ethnic minority groups in the northern regions, incorporating some distinctive elements. However, the emphasis on formality and material wealth that characterized the Song Dynasty (960–1279) did not persist into the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). Instead, various procedures were simplified, and a phenomenon of cultural integration between the Manchu and Han ethnic groups gradually emerged during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912). In the Republican era (1912–1949), influenced by the trend of Westernization, traditional Chinese wedding customs collided with Western-style civilized weddings, eventually evolving into modern wedding ceremonies that combine elements of both cultures.

The progression of society and various cultural, political, and economic changes significantly impact the representation and practice of religious weddings. Contemporary Chinese wedding practices exhibit a complex landscape: rural weddings still maintain a considerable continuity with traditional ceremonies, while urban weddings often bear traces of “civilized weddings” (

He 2018). On the other hand, wedding rituals tend to simplify, with traditional weddings being a clan affair, while modern weddings are often just a banquet. The shift from traditional to modern weddings in China primarily stems from the prevalence of individualism, which challenges the Confucian construct of a kinship-based ethical society, where family is the foundation of the nation and disrupts the formation of the family entity. Moreover, evolving marriage concepts, systems, and cultural diversity have eroded the solemnity and traditional characteristics of wedding rituals (

Hu 2019). The disorderly nature of modern weddings reflects the gradual obscuring of the original “righteousness” and diminishing significance of the ritual aspect. Wedding ceremonies mark the beginning of Confucian ideals of constructing family ethical relationships, establishing familial ties, and stabilizing the nation. Hence, the critical and inclusive inheritance of ancient “Six Rites” under the guidance of pre-Qin Confucian thought may, to some extent, call for a resurgence of ethical consciousness and aim to revitalize the sense of ceremony and spirituality in weddings. Although the “Six Rites” no longer exist, they have transformed into prototypes for modern-day proposals, engagements, and marriages in wedding ceremonies. Simultaneously, many wedding customs, such as bridal chamber pranks, lifting the bridal veil, and the post-wedding banquet, have been preserved as important components of ancient wedding traditions. Traditional Chinese weddings have transformed into a new cultural form and re-entered the public consciousness in modern times. In future research, it is imperative to contemplate the evolution and societal impact of traditional Chinese wedding ceremonies within the context of modern society. This consideration will better equip us to provide guidance for the preservation and innovation of contemporary Chinese wedding practices.