The Strategy of Interpreting the Daodejing through Confucianism in Park Se-dang’s Sinju Dodeokgyeong

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Dodeokjigwi 道德指歸 by Seo Myeong-eung 徐命應 (1716–1787);

- Chowondamno 椒園談老 by Lee Chung-ik 李忠翊 (1744–1816);

- Jeongno 訂老 by Hong Seokju 洪奭周 (1774–1842);

- Nojajiryak 老子指略 by Sin Jak 申綽 (1760–1828).

2. Hereticalization of the Daodejing in the 16th and 17th Centuries

Nowadays, people only see the absence of xing 形 (image) or zhao 兆 (sign), and say it is empty (空蕩蕩) […] For example, since Buddhists only discuss kong 空 (emptiness), and Laozi only discusses wu 無 (nothingness), it is impossible to know whether there is an actual li 理 in the Dao.

One human body has both li 理 (reason) and qi 氣 (energy). Li is highly valued, while qi is of little value. However, li is non-interference (wuwei 無為), while qi has desires. Thus, those who put li into practice, already foster their qi in the process. This is what a sage (聖賢) is. If you focus only on nourishing qi (yangqi 養氣), you will surely hurt your xing 性 (nature). This is what Laozi and Zhuangzi are.

3. The Purpose, Strategy, and Limitations of Park’s Sinju Dodeokgyeong

- Lin Xiyi’s 林希逸 Laozi Yanzhai Kouyi 老子鬳齋口義;

- Su Zhe’s 蘇轍 Laozi Jie 老子解;

- Dong Sijing’s 董思靖 Daodezhenjing Jijie 道德真經集解;

- Wang Bi’s 王弼 Laozi Zhu 老子注;

- Jiao Hong’s 焦竑 Laozi Yi 老子翼.

3.1. The Ethical Ground: “to Cultivate Oneself and Govern Others” (修己治人)

While he [Laozi] lived in seclusion, he wrote a book to define the Dao that he upheld and to reveal its meaning. Although Laozi’s Dao didn’t conform to the method of the [Confucian] sages (聖人). Nevertheless, Laozi’s intention was still to “cultivate oneself and govern others” (修己治人). Even though Laozi’s words are brief, the message is profound. For this reason, the numerous illustrations of the Dao [in DDJ] are valued and have been used throughout antiquity, up through the Han Dynasty. The ruling class such as kings performed ‘polite and wordless edification,’ while their subordinates practiced ‘clean and quiet politics.’ But, during the Jin dynasty, some scholars with great ambitions but who behaved recklessly, spread falsehoods and deceived an era. […] In the case of Lin Xiyi’s annotations for example, they’re all wrong, not one of them is right.

With the disappearance of the great Dao, benevolence and righteousness emerged. Once wisdom emerged, there also came with it great deception.Only when parents fail to be in harmony do filial children and loving parents emerge. And only when the country falls to chaos do officials with strong allegiance to the sovereign show their loyalties.

Loyal subjects prove their loyalty to their sovereign when the nation is in chaos. Thus, the fault lies with the chaos, not with the officials. Filial piety and love are discovered when there’s tension in the family. Thus, the fault lies in the tension, and not in filial piety or love. After the disappearance of the great Dao, people learned of benevolence and righteousness. The fault lies in the disappearance of the Dao, and not with benevolence or righteousness. In this regard, Laozi deserves a critical evaluation that he did not properly understand the essence [of the Dao].

3.2. The Cosmological Level: “Ti and Yong Have the Same Source” (體用一源)

The Dao refers to ti 體 or the ontological body, and the ming or name refers to the yong 用 or functional use. Dao has ming as its function, and ming has Dao as its body, but neither the body nor the function can be eliminated. Therefore, if Dao becomes Dao by itself, it isn’t the so-called “constant Dao” or eternal way (changdao 常道), because there’s no function to establish itself as the body or ti [of Dao]. Further, if the name or ming becomes a name or ming by itself, it is not the so-called “constant ming” (changming 常名), because there’s no ti to act by itself.

When Laozi uses the term “constant wu”, he’s actually referring to the ti together with the concept of the “constant Dao” and the “nameless” (wuming 無名). From this angle, Laozi attempted to understand the mysterious li 理 (reason, principle, or natural law) that encompasses all the other phenomena (xiang 象). Furthermore, the “constant you” discussed in this text refers to the yong together with the “constant ming” and “having name” (youming 有名). From this, it can be seen that all the phenomena that manifest themselves in the world “have their origin in the same one principle” (根源一理).

Li means that the yong is inherent in ti, this is the so-called “one root” (一源). Additionally, xiang means that “subtleness” (微) has no choice but to be included in “conspicuousness” (顯). This is so-called “gaplessness” (無間).

“Ti and yong originated from one” means that, although there are no traces of ti (“the ontological body”), there is already yong (“function”) in the middle of ti; and “there is no gap between wei and xian” means that wei (“subtleness”) is in the middle of the xian (“appearance or conspicuousness”). That is, even when heaven and earth do not yet exist, all things on earth are already prepared for it, that is why “there is already yong in the middle of the ti”; when heaven and earth are already established, there li is already present, that is why “wei is in the middle of the xian”.

3.3. The Dilemma: Daoist Ethics Established through Neo-Confucian Cosmology

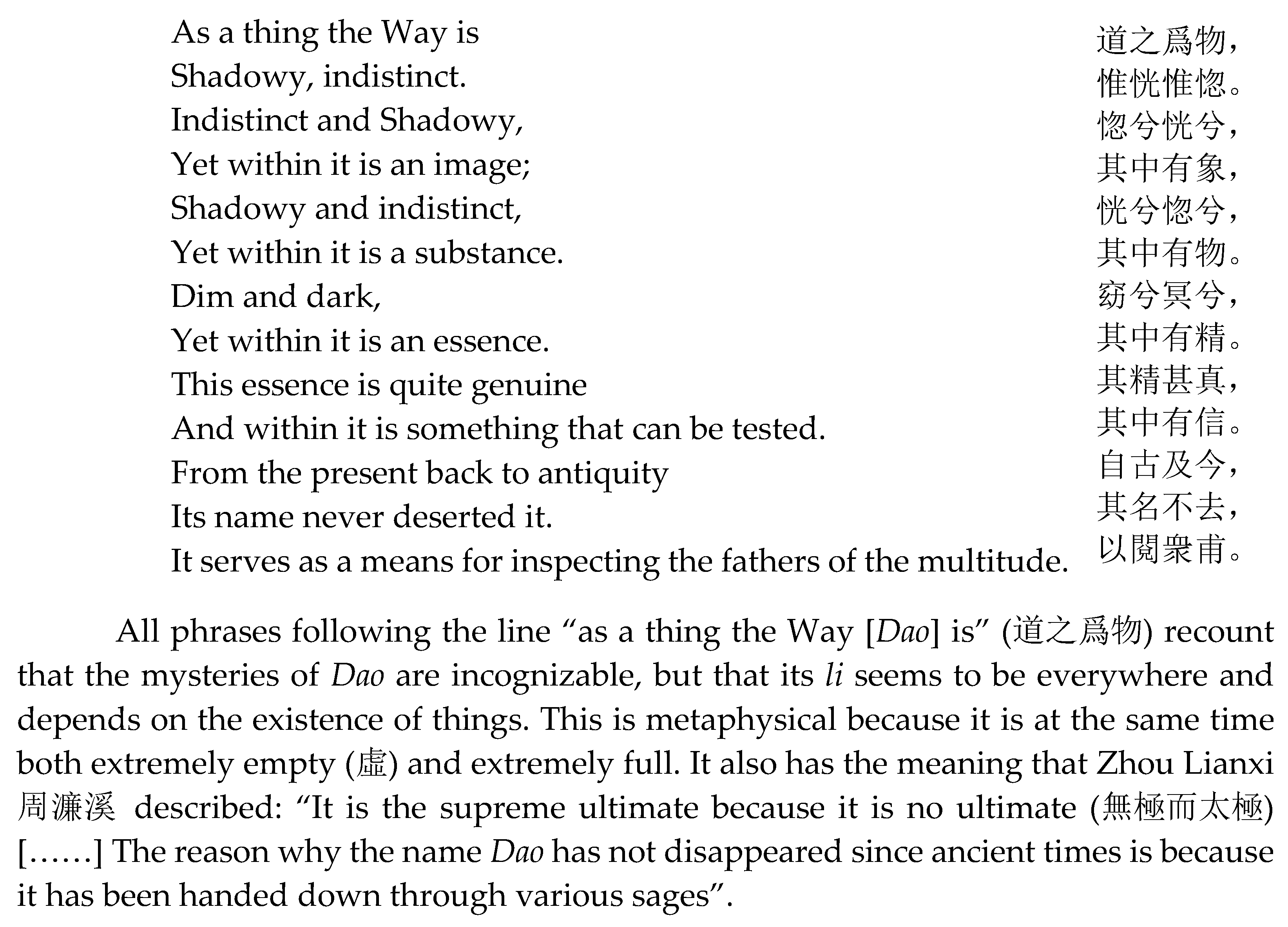

The distinction between Confucianism and Buddha only lies in the dispute about xu 虛 (emptiness) and shi 實 (substance). Laozi said: “Shadowy and indistinct, yet within it is wu 物 (a thing or object). Dim and dark, yet within it is jing 精 (essence)”. Thus, the substance and essence here are xu.

The ti of Dao is essentially xu虛 (empty). But what we see, hear, and touch, what we consider as one, and that what we think it is not light, nor dark, or endlessly extending, everything is close to “youwu” 有物 (things with shape) but eventually returns to “wuwu” 無物 (things without shape). Signs without signs and shapeless shapes resemble so-called metaphysical objects. Huhuang 惚愰 means indefinite or indistinct. The Dao is described as such because it seems both to exist and not to exist.

4. The Strategy of Integrating Daoist Ethics and Confucian Cosmology and Its Theoretical Limitations

“One” here refers to the supreme ultimate (taiji 太極). Laozi said that “the way begets one” because he took nothingness as the foundation (zong 宗). "Two” refers to yin and yang (liangyi 兩儀), and “three” refers to the “three powers” (sancai 三才). “Three begets the myriad creatures” means that three extreme poles are established and all things on earth emanate from them. The sentence “the myriad creatures carry on their backs the yin and embrace in their arms the yang” means that because all things have received the two qi of yin and yang, upon emerging they hold the energy of yin and yang on their back and in their heart so that they don’t separate. Chongqi (ji 沖氣) here is “empty qi”. There is nothing in all creation that is not in harmony with this “empty qi”. Therefore, everything on earth can coexist without doing harm to each other, and can maintain itself for a long time.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Sungsan Cho describes three types of approaches that nineteenth-century Korean scholars used to address ideological conflicts: (1.) achieving development through improved adaptive Neo-Confucian learning; (2.) critical and confrontational Neo-Confucianism; and (3.) overcoming Neo-Confucian thought through religious mentality (Cho 2016, pp. 119–21). |

| 2 | Teresa Hyun defined Silhak as follows: “The Silhak movement [occurring from the seventeenth to nineteenth century] comprised a group of Korean Neo-Confucianist scholars who attempted to go beyond the abstract metaphysical approaches of neo-Confucianism in order to find practical solutions to the agricultural, economic and social problems facing Korea” (Hyun 1997, p. 283). |

| 3 | According to Kim Seonhee’s research, “books and knowledge imported from China spurred the rise of broad scholarship and a growing interest in branches of practical knowledge” (Seonhee Kim 2023, pp. 53–80). |

| 4 | The rise of evidential learning in eighteenth-century Qing China had a far-reaching influence in shaping intellectual development in modern China and East Asia (Q. E. Wang 2008, pp. 489–519). |

| 5 | Jong-Chun Park (J.-c. Park 2016) discusses the Confucian anti-heresy discourses in late Joseon in more detail (pp. 113–43). |

| 6 | Seo Myeong-eung organizes the notes of his DDJ commentary Dodeokjigwi 道德指歸 according to the same conceptual structure that he used in his numerological work Bomanjae Chongseo 保晩齋叢書: the four images (sixiang 四象), the riverside scene (hetu 河圖), the polar regions (zhonggong 中宮), yin and yang (陰陽), hexagrams (liuyao 六爻), as well as measurements of time such as the 12 months, 60 weeks, and a cycle of 60 years (H. Kim 2004, p. 31). Moreover, Seo Myeong-eung describes the concept of taiji (the supreme ultimate) in the Daodejing through its connection to the human body, which is distinct from earlier Joseon dynasty Daodejing commentaries (Y.-g. Kim 2006, pp. 156–58). |

| 7 | Lee Chung-ik’s Chowondamno 椒園談老 and the DDJ annotation Dok Noja Ochik 讀老子五則 (Reading the Five Principles of Laozi) written by his teacher Lee Gwangryeo can be regarded as the typical examples. Kim Hyeongseok explained that although in Chowondamno Lee considers that Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism can communicate with each other in a most basic way, he gives priority to Laozi and Zhuangzi, followed by Confucianism and Buddhism (H.-s. Kim 2019, pp. 207–29). For a more specific analysis, see H.-s. Kim (2013, pp. 200–3). The ideological correlation between Lee Chung-ik and Lee Gwangryeo is described in H. Kim (2020a, pp. 275–302). |

| 8 | Hong Seokju argued in Jeongro 訂老 that the contents of DDJ were consistent with the words of Confucius. Because the discussions on jian 謙 and zheng 爭 in the DDJ were concerned with the question of how to avoid the coming of war in the Spring and Autumn and Warring States eras, Hong argued that the DDJ was a “book of benevolence” (T.-y. Kim 2017, p. 176). |

| 9 | Jo Minhwan researched how Joseon scholars integrated Confucian with Daoist theory (Jo 2005, p. 139). |

| 10 | The process of accepting DDJ on the Korean Peninsula was discussed in more detail in Seo-Reich (2022, pp. 999–1000). |

| 11 | Zhu Xi defined three guiding principles and eight ethical items as the purposes and approaches of Confucian learning in The Great Learning. The three guiding principles mentioned in the first verse of The Great Learning are “displaying enlightened virtue” (mingmingde 明明德), “loving the people” (qinmin 親民), and “the utmost goodness” (zhiyu zhishan 止於至善). The eight ethical items are “external cultivation of morality”, namely “to investigate things” (gewu 格物), “to attain knowledge” (zhizhi 致知), “to make intentions” (chengyi 誠意), “to rectify the mind” (zhengxin 正心), “to cultivate the self” (xiushen 修身), “to regulate the household” (qijia 齊家), “to bring good order to the state” (zhiguo 治國), and “to bring peace to all under Heaven” (pingtianxia 平天下). The above conceptual language and translations follow Johnston and Ping (2012). |

| 12 | The quotation from Zhuziyulei 朱子語類 [Sayings of Zhuzi] in this paper is based on the collection publicly registered in the “National Archives of Japan Digital Archive” (www.digital.archives.go.jp. accessed on 30 October 2023) and has been translated directly by the author referring to different annotations. Thus, this paper only made a citation note about the quoted volume of Zhuziyulei and refers to the public domain addresses of the original source (Zhu 2023g). |

| 13 | For more information about the differences in Yi Hwang’s and Yi I’s perspectives on heresy, see Jo (2009, pp. 48–49). |

| 14 | Kim Hakmok, the modern Korean translator of Suneon, insists that Yi I was able to interpret the DDJ, a heretic book in Joseon, because he was confident that he could interpret it from the perspective of Neo-Confucian logic as needed (H. Kim 2002, p. 298). |

| 15 | According to Geum Jangtae’s research, Suneon first appeared in an anthology of Yi I’s works in 1611, and some records show that Suneon was published in some select editions of Inner Works, Outer Works, and Additional Works. However, it is now difficult to find any book that actually contains Suneon, and even after Yi I’s death, any discussion on Suneon was avoided even among his successors (Geum 2005, p. 172). |

| 16 | Furthermore, Yi I thought that “to empty one’s mind” in the DDJ could be a methodology to correct a wrong disposition (qizhi 氣質) (H. Kim 2020b, pp. 106–7). |

| 17 | The following research provides various information on the background and writing process of Suneon: Yoon (2021, pp. 69–113). |

| 18 | Lin Xiyi’s Laozi Yanzhai Kouyi was completed in the 13th century and brought to Korea and Japan from the early 15th century on, and it gained huge popularity during the Edo period (H.-s. Kim 2010, pp. 257–68). |

| 19 | Kim Hakmok analyzed the commentaries cited or mentioned in Sinju Dodeokgyeong. This analysis shows that Lin Xiyi’s commentary was most often cited, namely in chapters 3, 5, 6, 19, 21, 27, 28, 46, 49, 68, 69, and 70. This shows that Park was paying special attention to Lin Xiyi’s point of view (S.-d. Park 2013, p. 37). |

| 20 | Hayashi Razan was a pioneer of Japanese Neo-Confucianism. He stayed at Kennin-ji Temple (建仁寺) between 1595 and 1597, where he studied Laozi’s and Zhuangzi’s thought based on Lin Xiyi’s commentaries. Hayashi Razan accepted Lin Xiyi’s viewpoint, about which he said: “Even though I dwelled upon old commentaries of DDJ, nothing is as clear as Kouyi 口義” (Ou 2001, pp. 275–78). |

| 21 | Following Lin Xiyi, Park quotes Zhu Xi the second most in Sinju Dodeokgyeong. Considering the magnitude of Zhu Xi’s influence at the time, it is worth noting that Lin Xiyi was cited even more than him. For a detailed study concerning the source of Sinju Dodeokgyeong commentaries, see H. Kim (2000, pp. 102–6). |

| 22 | For more information about the academic background and basic standpoint of Park Se-dang, see Han (2010, pp. 268–70). |

| 23 | Yi I rejected the common misconception that the DDJ only discussed qi 氣 and suggested the possibility that it could be interpreted through the concept of li in relation to qi as well (Jo 2010, p. 282). |

| 24 | Shin Jinsik explains how Park tried to identify new principles in order to steer political groups away from sources other than Zhu Xi’s doctrines (Shin 2009, p. 89). |

| 25 | Aside from the annotations by Weijin metaphysicians or Neo-Confucians discussed in this article, there were also commentaries from a Buddhist perspective like Shi Deqing 釋德淸 that also circulated among the DDJ commentaries in Joseon society during the 17th century. Because these commentaries had limited influence on related intellectual discussion during the Joseon dynasty, they are not discussed in detail in this article. |

| 26 | Park did not clarify the source, but concluded the comment with a stance almost the same as in the Zhuzi Pinjie 諸子品節: “This chapter is written by Laozi during the decline of the Zhou state when he was worried about reality, nostalgic of days gone by, and resentful of the world”. Here, Park Se-dang argues that it was an ironic expression left behind by Laozi in anger at the reality of the loss of benevolence and righteousness in an unrestrained world, not for the purpose of criticizing the virtues of Confucianism. This demonstrates that Park finds an explanation for Laozi’s standpoint that tries to minimize the ethical differences between the Confucians and Laozi. |

| 27 | Four aspects defined the division of the Joseon government and the construction of Korean Silhak: first, the relationship between the Dao and the Instrument in traditional Confucian scholarship; second, institution and civilization, as expressed in the phrases of “administration and practical usage” and “profitable usage benefiting the people”; third, growing interest in the historical importance of Jeong Yakyong’s scholarship; and fourth, consistent interest in the value of practicality (Noh 2023, pp. 277–310). |

| 28 | The big artificial combination here refers to earth, water, fire, and wind, which make up all things in heaven and Earth. According to Zhu Xi’s understanding, they mix and grow according to the karmic theory of Buddhism. |

| 29 | The translation of terms from Great Learning is based on James Legge’s translation, which was partly changed according to the author’s understanding, see Legge (1960, p. 356). |

| 30 | Wang Bi interpreted this as “Everything in the world is made of you, and the beginning of you is based on nothing, thus, to complete you, [everything] must return to nothing” (B. Wang 2011, pp. 113–14). |

| 31 | For arguments supporting this opinion, see the “Sinju Dodeokgyeong-e Natanan Park Se-dang-ui Sasang [Park Se-dang’s Thought in Sinju Dodeokgyeong]” chapter in S.-d. Park (2013, pp. 271–305). On the other hand, Park Se-dang interpreted Dao as working according to the li in his annotations on the Tiandi chapter of Zhuangzi in his commentary book Namhwagyeong JuHae Sanbo (Annotation and Edition of Nanhuajing). |

References

- Cheng, Yi. 2019. Yizhuan Xu [The Introduction of the Book of Change]. In Zhouyi Chengshi Zhuan. Translated by Jingsong Sun, Yunfei Fan, and Duanlin He. Beijing: The Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Sungsan. 2016. Ruling Intellectuals of the Joseon Dynasty in the 19th Century: Fractures and Possibilities. Critical Review of History 117: 119–52. [Google Scholar]

- Geum, Jangtae. 2005. Suneon-gwa Yulgog-ui Noja Ihae [Suneon and Yul-gok’s Understanding of Lao-tzu]. East Asian Culture 43: 171–231. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Kyung-duk. 2010. Park Se-dang Namhwagyeong Juhae Sanbo Jung-ui Saengmyeong-gwan [Park Se-dang’s view of life in his commentaries on Namhwagyeong Juhae Sanbo]. Youngsan Journal of East Asian Cultural Studies 6: 265–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hyun, Theresa. 1997. Byron Lands in Korea: Translation and Literary/Cultural Changes in Early TwentiethCentury Korea. Traduction Terminologie Rédaction 10: 283–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jo, Minhwan. 1997. Bak Se-dang’s Understanding of Laozi (I). Journal of The Studies of Taoism and Culture 11: 189–217. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, Minhwan. 2005. A study on the difference between the commentaries of Lao-Tzu in Chosun dynasty. Korean Thought and Culture 29: 139–68. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, Minhwan. 2009. The Study on the Yul-Gok’ Lao-Tzu commentaries ‘SunEon’ and Korean Philosophical phase [sic]. The Journal of Asian Philosophy in Korea 32: 45–74. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, Minhwan. 2010. A Study on the Change though about ParkSe-dang’ LaoZhuang commentaries [sic]. The Journal of Asian Philosophy in Korea 33: 279–304. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Ian, and Wang Ping. 2012. Daxue and Zhongyong: Bilingual Edition. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hakmok. 2000. Seogye Park Se-dang-ui Noja-gwan [Seogye Park Se-dang’s view on Laozi]. Journal of The Studies of Taoism and Culture 14: 99–123. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hakmok. 2002. Suneon-e Natanan Yulgok Yi-i-ui Sasang [Yulgok Yi I’s Thought appeared in Suneon]. Studies in Philosophy East-West 23: 297–314. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hakmok. 2004. Dodeokjigwi Pyeonje-e Natanan Bomanjae Seo Myeongeung-ui Sangsuhak [The Numerology of Seo Myeongeung in the Chapter Organization of Dodeokjigwi]. Journal of The Society of Philosophical Studies 64: 31–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hakmok. 2020a. Correlation between Five rules of reading Laozi and Chowon’s discourse of Laozi. Journal of Yulgok-Studies 42: 275–302. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hakmok. 2020b. The Emptying Mind of Lao-tzu and Zhuangzi in Suneon and Nam Hwa Gyeong Joo Hae Sanbo. Journal of the Daedong Philosophical Association 93: 105–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hyeong-seok. 2010. Commentary of Zhuangzi in the Chosun dynasty—Compared to the Studies on Zhuangzi of Lin Xiyi in the Southern Song period and of Hayashi Razan in the Edo period. Yang-Ming Studies 25: 257–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hyeong-seok. 2013. A Tentative Study on Relationship between the Three Religions in Lee Chungyik’s Commentary of Laozi, Cho-Weon-Dam-Lo. Yang-Ming Studies 36: 193–230. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hyeong-seok. 2019. A Study on Lee Chung-yik’s Perspective of the Three Teachings in his Commentary of Laozi, Cho-weon-dam-lo. Studies in Confucianism 46: 207–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Saemio. 2011. A crituque[sic] style of Yeon Cheon Hong SeokJu’s Kho Jeung Science and its implication. Journal of Korean Literature in Chinese 32: 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Seonhee. 2023. Choe Hangi’s Gihak: Universal Science and the Fusion of Eastern and Western Knowledge. Review of Korean Studies 26: 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Tae-yong. 2017. A Study on 19st Korea Confucian Hong Seokju’s the view of Laozi—Based on practical view of learning. The Journal of Korean Philosophical History 55: 161–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Youn-gyeong. 2006. The view of ‘Taiji’ in Seo Myong-ung’s Dao De Zhi Gui. Journal of Eastern Philosophy 48: 145–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, Din Cheuk. 1962. Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jong-Sung. 2017. Aspect of Ethical Harmonization and Conflict of Confucian School and Taoist School in Park Se-dang’s New-Annotation Tao Te Ching. Journal of The Studies of Taoism and Culture 47: 167–200. [Google Scholar]

- Legge, James. 1960. The Chinese Classics: Confucian Analects, The Great Learning, The Doctrine of the Mean. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jingde. 2020. Zhuzi wenji [Analects of Zhu Xi]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zehou. 2008. Zhongguo Gudai Sixiangshi Lun [The History of Ancient Chinese Thought]. Beijing: Joint Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Xiyi. 2010. Laozi Yanzhai Kouyi. Shanghai: East China Normal University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Peimin. 2017. Understanding the Analects of Confucius─A New Translation of Lunyu with Annotations. New York: State University of New York. [Google Scholar]

- Noh, Kwan Bum. 2023. The History of the Formation of Silhak in Modern Korea: A Preliminary Research. Seoul Journal of Korean Studies 36: 277–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Teki. 2001. Nihonni Okeru Roo-Syoo Sisoo-no Juyoo [The Acceptance of Laozi’s and Zhuangzi’s Philosophy in Japan]. Tokyo: Kokushokankokai. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Jong-chun. 2016. Youngnam Scholars’ Anti-Heresy Discourses in the Late Joseon: A Reevaluation of Inclusive Anti-Heresy Discourses. Philosophia 138: 113–43. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Se-dang. 2012. Park Se-dang-ui Jangja Ilkgi: Namhwagyeong Juhae Sanbo 1 [Reading Park Se-dang’s Zhuangzi: Namhwagyeong Juhae Sanbo 1]. Translated by Heonsun Park. Paju: Yurichang. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Se-dang. 2013. Park Se-dang-ui Noja [Park Se-dang’s Laozi]. Translated and Annotated by Hakmok Kim. Seoul: Yemunseowon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Seung-bum. 2019. Acceptance of Goguryeo’s Taoism and Laotzu Taoteching. Prehistory and Ancient History 61: 73–96. [Google Scholar]

- Seo-Reich, Heejung. 2022. Four Approaches to Daodejing Translations and their Characteristics in Korean after Liberation from Japan. Religions 13: 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Jinsik. 2009. Park Se-dang Nojanghag-ui Teukjing [Characteristics of Park Se-dang’s Study on Laozi and Zhuangzi]. Journal of The Studies of Taoism and Culture 31: 87–110. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Bi. 2011. Laozi Daodejing Zhu. Translated by Yulie Lou. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. Edward. 2008. Beyond East and West: Antiquarianism, Evidential Learning, and Global Trends in Historical Study. Journal of World History 19: 489–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Hwang. 1915. Toegye-Jip [The Works of Toegye]. Edited by Joseon Goseo Ganhaenghoe [Joseon Society of Classic Book Publication]. Seoul: Joseon Goseo Ganhaenghoe, vol. 12, Available online: https://docviewer.nanet.go.kr/reader/viewer#page=24 (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Yi, Hwang. 1958. Toegye Jeonseo [The Complete Works of Toegye]. Seoul: Daedong Munhwa Yeonguwon, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, I. 1990. Yulgok Jeonseo─Hanguk Munjip Chonggan [The Complete Works of Yulgok─Collection of Korean Anthologies]. Seoul: Minjok Munhwa Chujinhoe, vol. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, I. 2011. Suneon. Translated and Annotated by Hakmok Kim. Seoul: Yemunseowon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, ChunKeun. 2021. Reflections on Soon Eon of Yulgok: In Connection with the Development of Culture during the Joseon Dynasty in the 16th Century. Journal of Yulgok-Studies 46: 69–113. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, Sasun. 2008. Philosophical Aspects of Practical Learning. Seoul: Na-nam Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Xi. 2019. Zhouyi Benyi [The original meaning of the Book of Changes]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Xi. 2023a. Zhuzi wenji [Collection of Zhu Zi’s Writings]; no. 38. Harvard University Library. Available online: https://ctext.org/library.pl?if=gb&file=104910&page=2&remap=gb (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Zhu, Xi. 2023b. Zhuzi wenji [Collection of Zhu Zi’s Writings]; no. 48. Harvard University Library. Available online: https://ctext.org/library.pl?if=gb&file=202132&page=33&remap=gb (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Zhu, Xi. 2023c. Zhuzi Yulei [Analects of Zhu Xi]; no. 124. The National Archives of Japan Digital. Available online: www.digital.archives.go.jp/DAS/meta/listPhoto?LANG=default&BID=F1000000000000099022&ID=M2013082820073099292&TYPE= (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Zhu, Xi. 2023d. Zhuzi Yulei [Analects of Zhu Xi]; no. 126. The National Archives of Japan Digital. Available online: https://www.digital.archives.go.jp/DAS/meta/listPhoto?LANG=default&BID=F1000000000000099022&ID=M2013082820074599293&TYPE= (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Zhu, Xi. 2023e. Zhuzi Yulei [Analects of Zhu Xi]; no. 17. The National Archives of Japan Digital. Available online: www.digital.archives.go.jp/DAS/meta/listPhoto?LANG=default&BID=F1000000000000099022&ID=M2013082819570499255&TYPE= (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Zhu, Xi. 2023f. Zhuzi Yulei [Analects of Zhu Xi]; no. 67. The National Archives of Japan Digital. Available online: www.digital.archives.go.jp/DAS/meta/listPhoto?LANG=default&BID=F1000000000000099022&ID=M2013082820012999273&TYPE= (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Zhu, Xi. 2023g. Zhuzi Yulei [Analects of Zhu Xi]; no. 94–95. The National Archives of Japan Digital. Available online: https://www.digital.archives.go.jp/DAS/meta/listPhoto?LANG=default&BID=F1000000000000099022&ID=M2013082820041899284&TYPE= (accessed on 30 October 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seo-Reich, H. The Strategy of Interpreting the Daodejing through Confucianism in Park Se-dang’s Sinju Dodeokgyeong. Religions 2023, 14, 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14121550

Seo-Reich H. The Strategy of Interpreting the Daodejing through Confucianism in Park Se-dang’s Sinju Dodeokgyeong. Religions. 2023; 14(12):1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14121550

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeo-Reich, Heejung. 2023. "The Strategy of Interpreting the Daodejing through Confucianism in Park Se-dang’s Sinju Dodeokgyeong" Religions 14, no. 12: 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14121550

APA StyleSeo-Reich, H. (2023). The Strategy of Interpreting the Daodejing through Confucianism in Park Se-dang’s Sinju Dodeokgyeong. Religions, 14(12), 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14121550