1. Introduction

This paper is framed with Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s quizzing ontology and their geo-philosophical ruminations on space (

l’espace) or social spatialisation, place, and movement. I take their allegorical and historical figure of the nomad

1 in the context of antithetical frontier-dwelling Buddhist wanderers, divergent, if transitory, social forces at the borderlands. Recent borderland studies have seen a shift away from the bounded notion of the nation-state to a geo-spatial analysis involving the multifaceted processes shaping the imbricating margins of borderlands (

Horstmann et al. 2018). This is the intense social milieu of the nomad, occupying and holding a smooth space

2.

The politico-religious nomad entails an Othering tendency within the molar institutions of state, but located within its endo-exteriorities (

Leonard 2003, p. 196) A nomad or mobile life,

Deleuze and Guattari (

1987,

2010) argue,

is the intermezzo; it is not necessarily a permanent or fixed marginal condition, metaphorically situated between (striated) lines

3. The nomad figure was never intended as a fixed state of being, as nomad and the smooth were always susceptible to appropriation by the state and the striated (

Lundy 2013, p. 246). This is shown in the case studies discussed briefly in this paper on charismatic wandering monks, that, functioning between different lines and in time, may become domesticated through co-optation by the centre-nation.

The nomad in this sense was first alluded to in Deleuze’s doctoral research (published in 1968) in relation to distributive systems; a nomad nomos as a division among those who distribute themselves in open space (

Deleuze 1994, p. 36). It should be noted at the onset of discussing a religious nomadology that neither Deleuze nor, as two, Deleuze and Guattari, gave a great deal of attention to religious thought and practices—and hardly at all for the Asian Buddhist traditions (e.g.,

See and Bradley 2016, p. 4).

4 The (Oriental) despot (in terms of Wittfogel’s hydraulic theory) Deleuze and Guattari tell us “acts as a river, not as a fountainhead, which is still a point, a tree-point or root; he flows with the current rather than sitting under a tree; Buddha’s (Bodhi) tree itself becomes a rhizome...” (

Deleuze and Guattari 1987, pp. 21–22). Although loaded with ambiguity (noted by

See and Bradley 2016, p. 5), it makes sense in the context of the Buddha’s emergent (radical) spiritual network among his scattered and expanding itinerant early followers. These consisted of small groupings of heretic

samaṇas; new religious nomads in a new regional republicanism, cutting across the prevailing arborescent, coded, and structured orthodox Brahmanical space. Later, the Gauda Brahmin King Shashanka, consolidating and striating the northeast Bengali region in the seventh century, symbolically cut down the Buddha’s (Bodhi) tree at Gaya (

Jha 2016, pp. 5–6).

It should be noted here that

Deleuze and Guattari (

1987) never conceived of a non-linear, radical, or counter-hegemonic religion; at least where territorialising religions emerge autonomously outside of state organizations. They only saw religion—at least Christian monotheism in post-war Europe—as coterminous with the interests of the state, or as an element of state apparatus, converting the absolute into horizon (382–383).

This essay is not concerned with reading these two thinkers into some intellectual (Buddhist) space in which they seemingly did not even place themselves. Instead, it aims to refer to their combined relevant generic suppositions and musings as a means of interpreting the historic and lived practices (as radical soteriology (

Obeyesekere 1985)) of the politico-religious regional itinerants of Theravada Buddhism.

2. Nomadism and Molecular Practices of the Wanderers

The nomad trope, or its literal (quasi-) historical representation, contrasts with a sedentary (striated) existence.

5 A “sedentarist metaphysics”, in

Malkki’s (

1992) terms (that is history), takes for granted a hegemonizing norm that looks upon mobility or itinerant journeying (

Clifford 1997) through the lens of place, rootedness, spatial ordering, and notions of belonging (

Kabachnik 2009). Mobility has been the axis mundi of the nomads who have played a dynamic role in the early rise of civilizations and state formation (

Rana 2018, p. 251). The Oriental despotic state is discussed as a system of flows, with the current as a hydraulic model, non-arborescent. Nomads later came to represent a threat to the security of sedentary populations (

Cresswell 1997;

Peters 2006).

The religious nomads

6 or itinerant wanderers (e.g., the

paribbājaka) were as one seen as a concern to the emergent states seeking fixity, but as a contrast also seen as a regenerative source of desolate, enigmatic free-floating charisma. They were distributed across an open and limitless space of the nomos (

Deleuze 1994, p. 309, fn 6;

Taylor 1993, 164 ff), contra the sedentary city-state. The nomos is opposed to the law or the polis, it is “the backcountry, a mountainside, or the vague expanse around a city.” (

Deleuze and Guattari 1987, p. 420). These latter (non-) places were outside the city walls of the premodern Buddhist state, where religious ascetic nomads would stopover in the wasteland, charnel grounds, and forest enclaves. The religious nomads were then constituted as an “internalised exteriority, inhabiting the state but placed beyond the walls of the

polis” (

Leonard 2003, p. 197). The endo-exteriorities of the state (as well as beyond the borders), as discussed later, is often where the religious nomads are located.

Religious wanderers have a disaffection for topological commitment, breaking from striated space and, though spatially situated, possessing a territorial principle. But nomadism may also be conceived in the sense of an unfolding, flowing mobile thought (

Deleuze and Guattari 1987, p. 482) as sustained for instance in the meditative, introspective, and immanent “otherworldliness” (living in the world, but exterior to its order).

In the derivations of early mobile or nomadic Buddhism in Southeast Asia, we need to start with comprehending its Indic/Vedic traditions since wandering (secular and religious) was present as an “institutionalized delocalization” (

Rao and Casimir 2003, p. 221) since the (pre- and early Buddhist) late Vedic period. There were “zones of cross-cutting networks” (

Lightfoot and Martinez 1995, p. 474) with several criss-crossing categories of “settled” and “wandering” groups, whereby the forests and savannas symbolized the ambivalence of such zones that created new hybridisations. The smooth spaces which so preoccupied Deleuze and Guattari’s ruminations were the arid and semi-arid zones (for example in early history of the nomadic Scythians). These smooth spaces are conceived as exterior domains within stratified states consisting “of bands, margins, minorities which continue to affirm the rights of segmentary societies in opposition to the organs of state power” (

Deleuze and Guattari 1987, p. 397).

In time, mobility in the Indic plains was displaced by an emphasis on sedentism, territoriality

7, and boundary attachments, which resonate with the proto-state or primordial

Urstaat (

Deleuze and Guattari 2004, p. 237;

Smith 2018, p. 232). It is hard to imagine archaic or primitive societies not having some interaction with the imperial state and in some interior/exterior relationship. As the over-coding state evolves over time, it hides its despotic tendencies and allows new flows to escape from it. The wanderers, roving and living in the state’s frontier, firstly under the magician-emperors (

Dumezil 1988) operating by capture and binding, became more marginal over time in the (capitalist) axiomatics of the modern Hindu-Buddhist states.

The state tries to make disparate entities communicate as one (while nomad space is one that is noncommunicating, as with retreating ascetic forest monks avoiding normative merit-desiring town-based patronage). The state is where “points resonate together...diverse points of order, geographic, ethnic, linguistic, moral, economic, technological particularities. It makes the town resonate with the countryside. It operates by stratification; in other words, it forms a vertical, hierarchized aggregate that spans the horizon lines in a dimension of depth.” (

Deleuze and Guattari 1987, p. 478). This is important to the argument of the idiosyncratic wandering religious nomad, resisting stratification and the incorporation into the state’s communicative embrace.

The relationship of primitive religious wandering to the state is ambiguous. A fundamental task of the state, and its plane of organisation as

Deleuze and Guattari (

1987, p. 425) note, is to striate the space over which it rules or to appropriate smooth space for the task of communication. Modern states exhibit a homogeneous (political)

extensio with an immanent centre, divisible similar elements, and “symmetrical and reversable relations” (

Deleuze and Guattari 1987, p. 429). In Southeast Asian emerging (Buddhist) polities, this may also be understood in relation to

Tambiah’s (

1973) early “galactic polity”; the political pulls and pushes of centre-oriented but centrifugally fragmenting polities. The galactic polities embodied a pre-modern totalising paradigm in which social, religious, and cosmological orders were intimately connected. It was evident that transformations from traditional galactic polities to centralising modern nation-states initiated profound reformulations of the relationship between Buddhism and society. Emerging modern nation states, while maintaining many of the religious and symbolic functions of the galactic polity at the centre, sought to extend their spheres of influence to incorporate ethnic minority groups (defined by their identities and, thus, in molar configurations) and newly defined national boundaries in the periphery (

Schober 1995, p. 308).

It is a principal task of every modern state (in its “molarity”) within the dominating centripetal plane to annihilate nomadism in the periphery, as collective individuation to control migrations and to establish a “zone of rights” over the entire exterior; over all the “flows traversing the (stratified) ecumenon” (

Deleuze and Guattari 1986, p. 59). The abstract ecumenon refers here to everything that is striated, constant, or largely static in form, and where every substance is determinate and determinant. This defines the “unity of composition of a given stratum”, (

Wiley 2005, p. 92, fn 27). The state needs to fix pathways in all directions, which restrict “speed” (

Virilio 1986), as well as to relativise movement and regulate circulation. If the nomads formed the allegorical war machine

8, it was by inventing absolute

9 speed and movement, the law of the nomos, of the smooth space that deploys it, and of the war machine that populates it (

Deleuze and Guattari 1987, p. 426). When the state does not succeed in domesticating its interior or neighbouring space, the flows crisscrossing that state take on the position of the war machine directed against it and deployed in a hostile or rebellious smooth space. That is, conceived as a largely unpopulated space situated between upland or montane forests and domesticated farmland in the lowlands [with its “grids and generalised parallels”]. This is eventually absorbed/over-coded by the state (

Deleuze and Guattari 1987, p. 424).

However, a fundamental flaw with Deleuze and Guattari’s arborescent logic regarding forests/trees and connoting a hierarchy, verticality, and the movement of transcendence, is that while forests may seem to be spaces “striated by these ‘gravitational verticals’”, they clearly confuse “deterritorialised” trees from the forest, which they do not give much attention to in their work (

Brown 2010;

Bonta and Protevi 2004). In fact, as “outside” frontier zones, forests pose a considerable threat to the interiority (or endo-exteriority) of the striated state and its far-order formations (in

Lefebvre’s (

1991) sense).

My proposition is that religious nomadism in mainland Southeast Asia is active in these interstitial spaces, the forests and mountains, the unruly zones (

Scott 2009). There are of course no sea-scapes, steppe, or deserts in mainland Southeast Asia (i.e., Deleuze and Guattari’s smooth nomadic spaces). Forests are vectorial spaces which oppose reterritorialisation. It is the resistance of these nomadic spaces to the concentration of power that makes the nomad a threat to state control and incorporation. Keeping in mind too that the binarism of smooth nomos/striated polis or nomadism/state are both/neither as one may become the other (and immanent to each other). The co-optation or appropriation of wandering monks (capturing their free-floating charisma and perceived mystical powers) in the periphery into the centre-state patronage system is a good example of this. The power of smooth spaces may be yoked for the purposes of state control (

Lundy 2013, p. 238) and the capture of religious nomads’ sacred power to the nation-centre, even if state-forms are now in late modernity increasingly ambiguous entities (

Marder 2016, p. 502).

Nomadism, as in Deleuze and Guattari’s war machine, pertains more to a radical “erring” (in the sense here as straying/roaming/drifting) (

M. Taylor 1984, pp. 11–12)

10 or, as dissidence in its various forms (mental and physical), to a de-structuring and towards a multiplicitous notion of a politico-religious rhizomatic schema.

3. Political Religiosity as a Nomadic a/Theology

Here nomadism may be referenced in the context of an itinerant

radical political religiosity; as a subversive and deconstructive (Buddhist) a/theology (

M. Taylor 1984). The latter represents at the extreme scale the religious nomadic “liminal thinking of marginal thinkers” (

M. Taylor 1984, p. 12), where there is only mutability to lineal thought, the disintegration of fixed boundaries and of striated spatial practices. The erring a/theologian will always be viewed by the (Kantian) ontotheologian as a heretic, a heterodox thinker, one who strays from the “straight opinion” (

M. Taylor 1984, p. 13). Boundaries and frontiers, it is argued, are composed of interactive zones of crosscutting social networks, and in a Deleuzian sense, composed of lines of segmentation, intermediary “molecular fluxes with thresholds or quanta” (

Deleuze and Parnet 2002, p. 124) and evasive lines of flight or rupture across established segments or embodied strata.

In the functioning of the state, the sacred place of religion is fundamentally a centre that resists the obscure nomos. The

absolute of religion is essentially a horizon that encompasses, and, if the absolute itself appears at a particular place, it does so in order to establish a solid and stable centre for the global. In short, religion converts the absolute. Religion is, in this sense, a piece in the state apparatus (in both of its forms, the “bond” and the “pact or alliance”.) (

Deleuze and Guattari 1987, p. 422) Nomads do not provide a favourable terrain for normative religion; the persons of war are always committing an offense against the (state) priest or the god. It is only nomads passing from one point or region to another that have absolute movement and speed; an infinite succession of local operations, and an essential feature of their war machine.

Essentially, Deleuze and Guattari’s nomads

11 (in their lines of flight) have a fuzzy, vagrant notion of religiosity, which serves their needs and notions of the absolute. They are opposed to the state’s religious hierarchy and striated structures that are imposed to limit speed. Radical religious nomads may be compared to

Weber’s (

1978) free-floating charismatic, irrational “prophets” (representing the war machine), who may eventually become “routinised”, normalised, and institutionalised as in the encirclement of civic religion and in the ritual functioning of the “priest” (and Buddhist monk) (

Michon 2021).

Rousseauian civic religion, it is argued, is inclined to project a universal or spiritual state over the entire ecumene, as a rigid, striated state space

12 and is not without ambivalence at the margins. This is why exemplary prophetic or charismatic (

Riesebrodt 1999)

13 and ascetic spiritual leaders often emerge from distant forests, from the mountains, even marginal zones of social formations in the metropolis (

J. Taylor 2008) or emanate from the intermediary “uncivilised” borderlands.

This is the religion as an element in a war machine (as in early Christendom, the “holy war” as the fire of that machine). The prophet, as opposed to the state personality of the king and the religious personality of the priest (or the monk of civic national religion), directs the movement by which “a religion becomes a war machine or passes over to the side of such a machine” (

Deleuze and Guattari 1987, p. 423).

In early regional histories, there were smooth spaces of secular and religious millennial movements found among the oppressed (

Landes 2011;

Desroche 1969, pp. 31–32), a cosmological imaginary and desired societal transformation which often involved frontier nomads, including regional charismatic monks and nondenumerable ethnic minorities (becoming-minor) and/or indigenous peoples, challenging the state apparatus. Historically, this would often involve sudden and radical shifting conceptions of power (

Keyes 1977, p. 285) and a growing resentment of the centre-nation dominance among marginal people in marginal places. This was even the case of the royalist Bangkok-based 1902 state ecclesiastical reforms and its ramifications for vernacular

vinaya (monastic) traditions, as in the north of Thailand, as noted for the charismatic regional leader Khruba Siwichai (1878–1939) and his distinctive ethnic monastic pupillage. This pupillage includes the late Khruba Khao Pi who had a wide following of Northern Thai devotees and from the Karen minority people (

Cohen 2021, pp. 93–94), and more recently the ethnic Shan/Tai Yuan Buddhist monk Khruba Bunchum

14. These nomadic northern Thai khruba monks are regarded as persons who have accumulated considerable “merit-(power)” (

ton bun) and latent supernatural powers (see

Nasee 2018).

A great deal has been written about Bunchum in the past decade or so, noted to have traversed back and forth across the borderlands of northern Thailand, Myanmar, and into Bhutan (

Jirattikorn 2016;

Cohen 2000,

2001)

15 now semi-captured through centre-nation patronage, by the hard segmentary lines of the state, Bunchum maintains his charisma through his occasional lines of flight (

ligne de fuite) across borderlands. His wanderings were an intent to evade state control (Thai and Burmese) and the desire for freedom from state control and state-backed sangha (

Cohen 2022;

Tatsuki 2017). Bunchum in fact recently emerged from two years in a remote cave on the borderlands in the autonomous Shan state. His mental state of health suddenly deteriorated recently at a Buddhist ceremony in Muang Ton, Myanmar, and as royal capture was sent to a Bangkok hospital directed by the king. In fact, Bunchum has had two long meditation retreats in remote caves. The first, 2010–2013, in Lampang Province, Northern Thailand, and the second was in Tham Luang Muang Kaet, Muang Sat, in the Shan State. He spent another three years at Tham Luang Muang Kaet, ending this retreat on 29 April 2019.

Another example is Khruba Theuang, a similarly charismatic frontier monk made popular among the Palaung (Dara’ang) people in northern Thailand. The Palaung are highland Mon-Khmer speakers with a long vernacular tradition of Theravada Buddhism formed at the interstices of the state (located in the Thailand–Myanmar–China borderlands). Theuang was similarly absorbed into the molar devotional embrace of the Thai nation-state through city-dwelling Thai devotees seeking out new and novel sources of untamed charismatic authority in the periphery (

Ashley 2012).

There are also sites of resistance located in the frontier as

Tanabe (

2022, pp. 22–28) explained in relation to the “deterritorialised” and minoritarian space of the King’s Mountain hermitage in Northern Thailand. This was initially established by a wandering hermit (

ruesii) with a utopian vision named Phor Pan (1932–2016) (see also

Cohen 2019, p. 157).

16 Later, after his demise, it was as a spiritual site for an eclectic female “Yogi” capturing an array of Hindu-Brahmanical and Buddhist symbols and images. The hermitage was initially established in opposition to the territorialising forces and the striations of national Buddhism. As Tanabe notes in the case of Phor Pan, “what we will see is ‘hermits’ and ‘yogis’ in the orbits in which they have taken flight (

la fuite) to transform themselves into something else, escaping the hegemonic Buddhist regime” (26). The Thai state religion seemingly has always encountered problems in its dealings with religious nomads and in normalising their radical and marginal practices.

4. The Centre-Nation and the Prophetic Machine

Millennialism as a politico-religious war machine has at is core the notion of prophecy. It may be argued that prophecy (or here one could contend, the historic moments of millennialism) triggered a conversion of religion into a nomadic war machine, mobilising and liberating and creating (absolute) deterritorialization. This possessed such force as to even turn its imagining of a properly spiritual absolute state back against the actual or virtual state-form (

Deleuze and Guattari 1987, p. 423).

Deleuze and Guattari (

1987) defer to the insightful early analysis by

Pierre Clastres (

[1974] 1989) of (South American) Indian prophetism, which challenged the established chiefs using the formers’ “prophetic machine” to generate support against the chiefs, resulting in a reversal of power in favour of the militant prophets. In the “othering” (as modalities of difference in power relations rather than dichotomous categorisation) discourse of the prophets, there may exist the seeds of the discourse of power, as

Clastres’ (

[1974] 1989, pp. 217–18) noted, and “beneath the exalted features of the mover of men, the one who tells them of their desire, the silent figure of the Despot may be hiding”. In other words, the power of prophetic speech may be the locus where power

tout court originated in the emergence of the (molar) totalising (rigid, and over-coded in terms of the capitalist axiomatic) state and in its normalising apparatuses.

In understanding centre–periphery relations, we need a historically informed and concrete analysis of actual hierarchical social relations of power, and how power is structured. And of course, power ratios may shift so that core groups (normalising apparatuses) may always be likely to lose their dominance to varying degrees, which is why the centre must always maintain control over the (potentially rebellious) margins.

It would seem, then, that the centre-nation cannot necessarily hold its own, driven to order things, especially in its relationship to vernacular institutions such as religion, the “church,” or the Buddhist monastery, as “things (may) fall apart; (which) the centre cannot hold” (

Yeats [1919] 1989). Here, a new transgression and critical proxemics underlies normative rules and practices, as we may note in cultural encounters between sacred and ordinary persons and things. In previous work,

Taylor (

2008) has written about the implications for a vagrant postmodern urban religiosity that emphasises mobility, ambiguities, and transitions in terms of social and geopolitical spatialisation. These are sites of encounter, which are transitional, mobile, and flowing (

Augé 1995); third spaces that engender in a late modern sense a “nomad religiosity” (

De la Torre 2015).

5. Religious Nomadism and the Wandering Rhizomatics

In a general discussion,

Vilém Flusser (

2003, p. 43) noted that nomads are people who pursue some purpose or goal in their wanderings, planned or unplanned. In pre-modern Thailand, roaming or travelling from place to place has long been associated for example with the quest of young village men to risky and indeterminate places (of nature), often far from immediate kindred and the familial village. Travelling by whatever means: bus, foot, oxen cart, or by train; the purpose was as much in the journeying itself through transitional non-places as in the arrival (the goal) at a (known) place. In early twentieth century Thai-Lao/

Isaan frontier society, such movement has always been practiced for various reasons, as in “searching for (good) rice fields” (Thai:

Ha naa dii) (

Fukui 1993, p. 313); especially when the frontier and its wild forest ecosystems were still considered “open” for domestic capture (i.e., the period 1957–1977) (

J. Taylor 1998, p. 41). But in this case, it was always movement towards the possibility of new settlement and fixity (

Sutherland 2014, p. 936).

At the time of the early twentieth-century centralising monastic reforms, the religious nomads were seen in its extreme as a form of vagrancy. It should not be surprising then that the early forest-dwelling wanderers were considered to be nothing more than vagabonds (Thai: phra-jornjat), homeless mendicants, spawning incredible stories of their spiritual life and practice as they travelled on foot on the marginal interstices of the striated space of the towns and the state borders, spurning the city-state polis. It is also a condition of a body both inside and outside (the world), a pure plane of being nowhere and in no (particular) place, and, thus, clearly, in a sense, marginal and absolute. Religious wanderers following a self-regulated nomos would establish their routes, which only they would know, and create a new networked socius in isolated sites or camping points along the way.

However, these monks would not have a permanent position of established relationships. As in early twentieth-century monastic wandering, monks would engage in short-term evasive tactics (

de Certeau 1984) that confused and frustrated the state, which was attempting to co-opt them into newly regulated, molar structures of the modernising royal Siamese reforms (as state “royal science”). This reterritorialisation of wandering monastic ascetics eventuated in the absolute domestication of forest-dwelling monasticism at a time of rampant insurgency in the frontier in the mid-1960s–late 1970s. It was considered best to domesticate the periphery under the compelling force of monarchy-sanctioned patronage conjoined with state religion in those heterotopic borderlands (

J. Taylor 1993).

6. The Forest Monk Phra Ajaan Man Phuritatto (1870–1949) and Molar Lines of the Modernising State

Phra Ajaan Man’s journeying was undertaken during a process of state capture and reterritorialisation of the far provinces. The peripatetic ascetic monk at the early stages of his travels was regarded with considerable suspicion at the centre-nation, though later in his life, after he was co-opted by the state, was a de-facto frontiersman (war machine capture) for the state’s ideological apparatuses. The processes of reterritorialisation undertaken during modernisation starting in the early twentieth century actually disrupted and reorganised national geographical/spatial codings. The unchartered and wild places of the entire frontier ecumenon at the time disturbed the interiority of the nation-state, shaking it from its complacency. Bringing the periphery of the sovereign nation and its marginal ethnic identities and heterogeneous religious practices that are located in these far provinces into the centre was the primary task of the state and its modernising, isomorphic, and regulating schema.

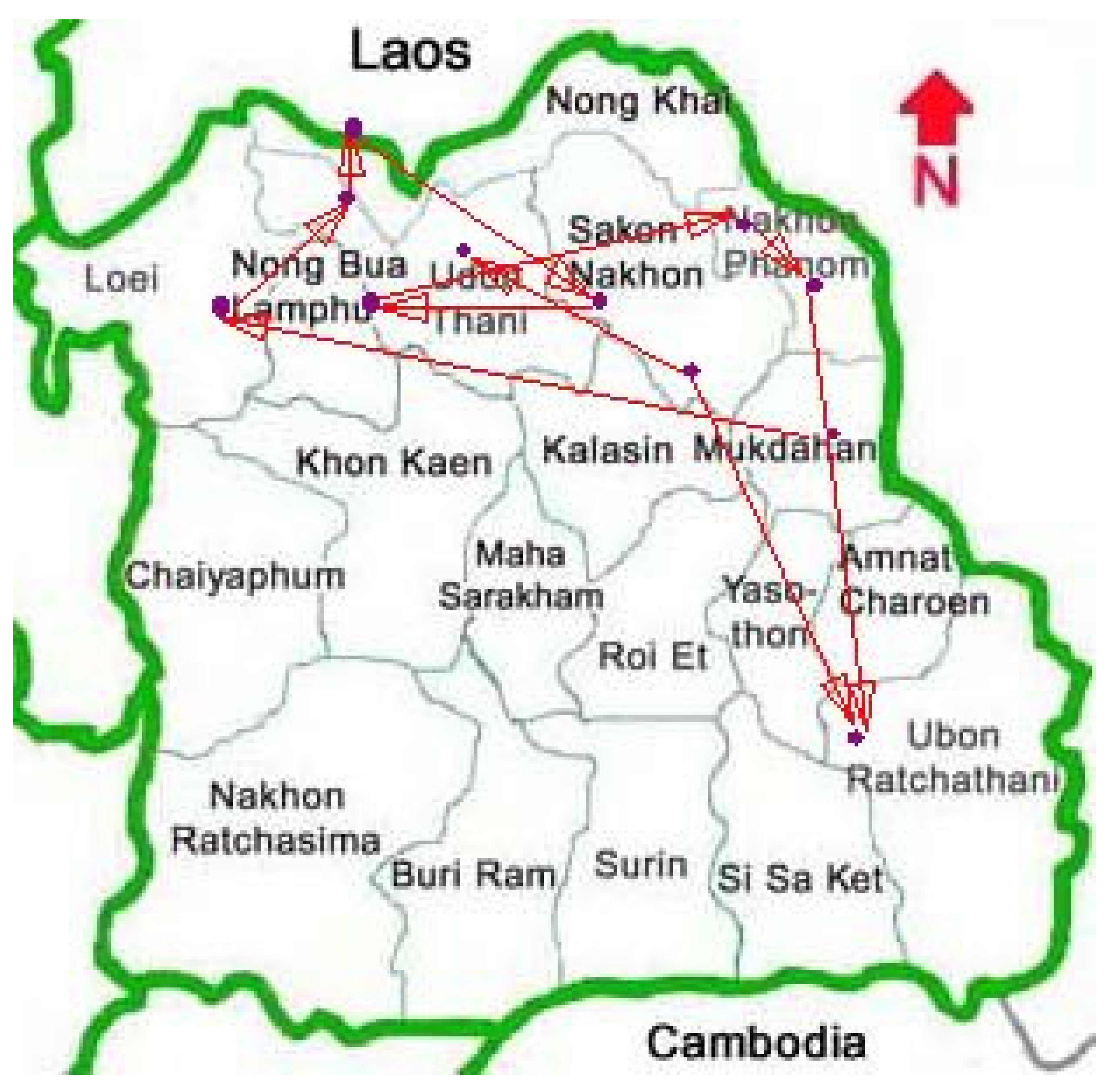

Phra Ajaan Man (an ethnic minority village-dwelling Lao-speaker in an ethnic Siamese/Thai majoritarian state), in his topological wanderings (

Figure 1) as a sanctioned reform-ordained monk (albeit forest-dwelling), was complicit (if unknowingly) in a period where religion was a religiopolitical means for ensuring absolute state capture. In fact, a century earlier, articulations of ethnic Lao identity, language, and music were forbidden in the Siamese capital (

Streckfuss 2012).

In the state’s appropriation of Phra Ajaan Man, once an elusive vagabond monk, later in his life started to acquire a particular history, a connecting temporal lineage, and an identity embedded in sanctity such that the state could understand. He was then transformed into a national saint, at a historic moment when the centre-nation needed the charisma of new virtuosi in nation building. He had turned to the ancient codes and worked from within the normative religious establishment; but at the same time, he remained largely unrestricted or aloof from its dominant ethnic and nationalistic embrace.

Phra Ajaan Man remained in the open, smooth space, of topological mobility, following a modus operandi of a religious nomad. The more the centre-nation (initially through royal oblations and visitations by royalty from the national capital) moved towards him; the more he retreated, and in so doing endorsed his recognised reclusive charismatic authority. His forest monk disciples, of which there were many second and third generation, were not so fortunate and through the capitalist axiomatic of the modern state became domesticated. As Buddhist “saints”, their physical bodies, material and symbolic, reliquaries, and monasteries were sanctified as the locus of ritual devotion and deification.

7. Creation of a Buddhalogical Space (as Cosmic Geography) and Nomadic Science

In the context of wandering Buddhist mystics and travelling monks affiliated to various lineages over the span of early history, territory was transformed and consecrated (

Swearer 1981, p. 38). The quasi-mythical seventeenth century Siamese monk Luang Phor Thuat (who was reputed to have died in 1682 in Perak, Malaysia), in accordance mainly with oral tradition, wandered in the Malay Peninsula. He was later to become a central figure in a thriving cult of amulets (the first batch made in 1954) and was one of the most popular and allusive mystical figures in Thailand, especially in the central and southern provinces (

Maud 2007). Thuat, emplaced in the inviolability of the centre-nation, became a symbol of Thai authoritative control over the southern borderlands.

Thuat, essentially, was a territorialising figure. Although he was supposed to have lived long before the lineages of acclaimed modern wandering monks in the borderlands of the north and northeast of Thailand, Thuat shares much of the ideological functions of these monks in the early (proto-) state formation at the borderlands. During his life, there was intense regional ethnic and political conflict in the pluralistic peninsular, especially involving Ayutthaya and Singora (Songkhla, which was under Muslim Sultanates) (

Dalrymple and Joll 2021). Indeed, the cult of Thuat in recent times was actively promoted to consolidate the notion of nation-state on the southern borderlands (

Jory 2008); a conflation of interiority or essentialism of the state and its nomadic exteriority, now reterritorialized to the codings (its axioms and principles) of the nation-state. This created a considerable problem for the state, which has long had concerns with its “nomadic or itinerant bodies...(and) which undertook to conquer both a band vagabondage and a body nomadism” (

Deleuze and Guattari 2010, p. 26).

The ancestry of religious wandering in Thailand not surprisingly has ancient Indic roots, as mentioned earlier, much of this going back as far as the quasi-mythic late Vedic age. Mobile missionaries and merchant travellers were then part of the Indianisation of mainland SE Asia

18 and later the establishment of a hybrid Mahavihara

19 version of what today we refer to as Theravada Buddhism. This was known as Lankavamsa/Lankawong, the medieval Sri Lankan lineage. The “New Lankawong” were the Araññavāsī, a forest-dwelling sect around the thirteenth century.

20Religious wandering in Buddhist Southeast Asia, especially its correlate ascetic practices (

dhutaṅgas), have its emergence in modern practice in detailed non-canonical fifth century Sri Lankan work. Ascetic wandering as non-attachment to place is concerned with the mental and bodily purification. Here eremites journeyed to isolated meditation sites in a practice leading to the destruction of yearning and desiring (Pali:

āsava). This was eventually as a means of attaining spiritual liberation (in a not always clearly defined normative sense). Mural paintings in two nineteenth century Bangkok royal temples, Wat Sommanat and Wat Bowonniwet, (

J. Taylor 1993, pp. 42, 71, fn 6) depict nomad ascetic technologies that were undertaken on the outskirts of the civilised cities and towns. These practices of contemplation on decay and death in charnel grounds outside the city walls shatter the permanent nature and conceptualisation of the body as anything but transient, fluid, and transformative in nature.

The ascetic technologies of meditation included seeing the basic thirty-two portions of the body spread in front of the meditator, constituent parts as separate from its unity of being and, through revulsion of attachment to form/being achieve a liberating disinterest of ego-self-identification. In this manner, we may say (taking a term from Felix Guattari): “I is an other”.

21 In this form of religious nomad science, it is more than an individuated identity: it is a multiplicity of (all) others, but also a singularity, a univocity of the elements of being.

There are interesting comparisons here to early fourth and fifth century deterritorialised wandering Christian ascetics, who never stayed long, and were resented by factions of the establishment church who wanted them to remain in monasteries and engage in what they regarded as useful spiritual labour servicing the needs of growing urban populations (the city-state [polis]). These (Christian) wanderers in their line of flight felt that a detachment from the world and its responsibilities in their rhizomatic wanderings would establish a closer spiritual affinity to God (

Caner 2002).

Thus, ascetic wandering seeking purification is not fixed in time and place. Instead, it may be argued that it is situated in a transitional non-place; it is in the line of flight itself that the enlightenment factor is realized, passing through and lessening all attachments to being-in-place. In the enlightenment factor, there is no sense of time or place. All ties and connections are suspended, as in meditation; time stretched to a sort of unbroken present moment (

Braidotti 1994, pp. 18–19). Forest ascetic (

dhutaṅga22) sites on rhizomatic routes may be considered as waystations or non-places; something of a cultural anomaly, abandoned and ambiguous. In the ancient

Vedas forests (

aranya) were the sacred “gaps” that were situated between established human settlements (

Malamoud 1976;

J. Taylor 1993, pp. 247–50).

The forest

dhutaṅga sites are separated from a world of culture, rootedness, and convention and instead located in an-Other space; that of separation, detachment, and a ground of liberation. The status of the heterotopic forest

dhutaṅga sites is in marked spatial contrast to the more embedded, static, or emplaced cultural notions of space, as in demarcated national parks, community centres, and geometrically established rice fields. Thus, while forest monks are situated on the rim of the civilizing state (the smooth, non-linear nomos), the boundaries of the local village (the polis), and, thus, separate from these forces of modernity, they are in another sense integral to the social whole and to the core cultural values that underlie popular religiosity (

J. Taylor 1993, p. 303). This is part of the paradox of modernity confronting the

sangha (monastic collective) of forest monks.

Although capturing the sentiment of the contemporary wanderers in Thailand, the ancient

Vedic verse that states “Flower-like the heels of the wanderer...All his sins disappear, slain by the toil of his journeying” (

Bhardwaj 1973) precedes, in a time before time, ethnic-Thai constructions of nomadic religion (and logically, the Indianisation of Mainland Southeast Asia). The Vedic

23 and post-Vedic poetic verses (

gāthās) share some thematic similarity, and in “Brahmanic, Buddhist, and Jaina texts these should be seen in context of the broader Indian proverbial-gnomic and didactic literature: sayings, aphorisms, maxims, and precepts originating in oral tradition” (

af Edholm 2021, p. 39)

.)

The middle-Indic liturgical language that we know as Pali (possibly a hybrid of several early Prakrit dialects) and its literature as we have it today, may be seen in the sense of a Deleuzian minor language (

Deleuze et al. 1983,

1984) within the greater Sanskrit Brahmanical tradition (the unchanging Indic high language of the gods). The language was deterritorialised in a fractured and changing political space. It generated an active solidarity among religious minoritarians (early Buddhist

samaṇas) in the context of a structured, hierarchical, and caste-dominated Brahman world, which the Buddha was resisting. As a heterodox spiritual teacher, the Buddha initially had small ascetic bands moving about in the endo-exteriority of the new republican states, and to eventually dominate the centres.

In his recent work,

af Edholm (

2021) clearly outlines the classic Indic literary origins of the wandering ascetic tradition since the Vedic epics where exhortations to

caraiveti/charaiveti (Sanskrit word meaning to “keep on walking”) resound throughout the early

gāthās. In such a way that we are told, “Indra is the friend of the wandering man [

carant-]” (

af Edholm 2021, p. 36), while the later Brahmanic and non-Vedic poetics express the ideal of the permanent wandering, as we see in the Buddhist texts; walking as the bodily expression of liminality (

Olivelle 2007). The Vedic

brahmacārin was a notion of the ideal wanderer and a forerunner to the Brahmanic and Buddhist renouncer (

parivrājaka), “going forth into homelessness” (

af Edholm 2021, p. 44). It is quite clear that the early Vedic and Brahmanic traditions of solitary, itinerant mendicancy, prefigured the latter wandering Buddhist renunciant.

Wandering alone and solitary like a rhinoceros has its roots in the Jainas (gāhās [

gāthās]) (

af Edholm 2021, pp. 48–54). The solitary wandering mendicant (“trackless”, the ascetic leaves “no trail”; s/he travels unnoticed and without a destination) (Olivelle in

af Edholm 2021, p. 59) clearly contrasts with the monk who stays permanently at a fixed place of sanctity, the monastery and a space of royalism. However, the nomadic life in settled early Buddhism became a temporary renunciatory or seasonal phase as Buddhist eremites must adhere to a monastic residence at least during the rain period (four months in early Indian Buddhism), and by the regulations of the state administration in the period of Chulalongkorn’s (r.1868–1910) modernising Siam, thereafter nominally controlled by centre-nation.

Patrick Olivelle (in

af Edholm 2021, p. 42) suggests that the Vedic wandering epic “the Song of the Wanderer”, the Aitareyabrāhmaṇa, composed in Videha during the mid-first millennium BCE (an area and a period connected to the rise of Buddhism and Jainism) in fact “echoes the earlier (semi-) nomadism of Indo-Aryan tribes”, who alternated between life on the move and settled life (

kṣema). The Indo-Aryan tribes were the Indo-European pastoralists who journeyed from Central Asia into northern borderlands of South Asia bringing with them the Proto-Indo-Aryan languages.

In the religio-political context of movement from various sites (as liminal places or as fixed points along a nomadic stratum), it was always borderlands that prefigured as important to the emergent tribal kingdoms and later as new states needing determined striations and rigid lines of the polis. af Edholm also noted that although “Brahmanic and Jaina renouncer-traditions were more successful than the Buddhist one in keeping alive itinerancy”, there are clear similarities between late Vedic, neo-Brahmanic, early Jaina, and early Buddhist gāthās on the benefits of wandering alone (

af Edholm 2021, p. 57) and following well used nomadic tracks.

This wandering theme, exemplified in this

Vedic verse and later Pali canonical literature (especially, as noted above, in the various gāthās), resounds in the discourses of forest (Buddhist) monks in relation to the location of the body in space, even of the nature of the body itself, where, as the late Ajaan Chaa Subhaddo (1918–1992) said, “time is only breath”. This has resonances to the Deleuzian/(Kantian) sense that time is the interiority in which we are, in which we move, live, and change; and in the notion of constant fluxes, flows, and desires constituting a time-reality (

Deleuze 1994, pp. 82–83). It may also be compared with a metaphor of a house as body, one that is not owned, but only temporarily rented during the countless cycles of life...the many and well-worn tracks. In a sense then, religious nomadism is considered to be outside of time and interior to it (as in subjective experiences of meditation).

Nomadic monks maintained their lines of flight across the Thai–Lao–Burmese landscape at least until the state-centred monastic reforms and controls during the 1902 Royal Sangha Act. The monastic wanderers wanted to ensure a free play of possibilities in order to achieve their ultimate otherworldly purpose. As

Flusser (

2003) noted, nomads pursue some purpose, which for the religious wanderers is absolute release from the conventional socius (in a Deleuzian sense) (

Bialecki 2018)

24, production, and desiring-becoming.

8. The State and Its Transformations, the War Machine and Its Smooth Religio-Counter-Sites to Becoming-Molar

As the state started to see wandering as transgressive, monks were exhorted to remain in-place, at particular monasteries and simultaneously co-opted into the ecclesiastical state hierarchy. This deprived them of their autonomous power gained from moving about freely in the margins. It was this same marginal charismatic power, potentially oppositional, that the state reterritorialized and institutionalized. The centre-state ensured this was effective through networks of elite patronage with their immoderate oblations to frontier-dwelling forest monks, whose austere mystical reputations were recognised (from the early 1960s onwards) as now properly orthodox as the spiritually accomplished virtuosi brought in from smooth space. This autonomous power of the wanderers was maintained through spontaneous movement in ambiguous, smooth space as politico-religious counter-sites (

Foucault 1986, p. 24). It is clear that nomadic movements interrupt settled (hegemonic) cultural presumptions. These movements obscure nomos, as in the case of the absolute of normative religion, its cultural, philosophical, and geo-political horizon that encompasses and defines boundaries and territory (

Connolly 1994, p. 33).

In their deliberately elusive flight from state officials and rich merit-seeking urban followers, the monks’ journeying would take them to various abstruse localities, even across contentious new national borders inscribed during Siam’s late-nineteenth century imposition of royal science (King Chulalongkorn’s rule) in the far provinces of the nation-state. These marginal localities, or spaces of representation, were chosen sites for unrestricted spiritual practices. This was a case of entrenched royalism (its axioms and principles), of supreme molarity (the king bringing the state with him), infiltrating and appropriating nomadic practices (nomad religious science) imbued with its topological movement and flows.

The countryside in the outer provinces at the turn of the twentieth century was the domain of lawless roaming bands, moonshiners, and cattle-rustlers. It is understandable that the social, ecological, and political space in which wandering monks (earlier not having official sanction) moved about was considered problematic by the state. The centralising state in the period of early modernity had little control in the far provinces. Because of the ambiguity of these smooth nomad spaces, there is a mystical fear attached to objects and persons located there. In this sense, boundaries are important as they delineate the temporal normal from the “abnormal” or spatial “Other” (

Leach 1976, pp. 35, 82).

The religious nomad would temporarily reside in largely inaccessible forest or mountain domains some distance from isolated farming communities or settled hamlets, deserted monasteries, or in cremation grounds outside villages. Although not staying for long in these (perceived dangerous) ambiguous and heterotopic sites, they would, indirectly through their bodily presence and rituals, transform these transitional sites into state-sanctioned sacred places.

These wanderers, not delimited by place, would move spontaneously back and forth across the borderlands between Thailand and ethnic enclaves in Myanmar, or between Thailand and Laos, in a statement of resistance to the imbrication and regulation of the state and its ecclesiastical authority. Religion is, after all, a piece of the state apparatus (

Deleuze and Guattari 1987, p. 422). These were sites of fear, forbidden and restricted, sources of unpredictable power shared with wild animals, the spirit world, stateless persons, outlaws, and insurgents (

Davis 1974;

Stott 1991, p. 144). Mary Douglas had earlier referred to these as “inarticulate areas, margins, confused lines …beyond the external boundaries” (

Douglas 1966, p. 98;

Leach 1976, pp. 33–35).

25The wanderers would come and go, and traverse over forbidden and potentially dangerous terrains, in between and among (yet untainted by) the culturally disturbing effects of an established order (

de Certeau 1984, p. 34). This was an intermezzo existence moving between points marked for significance such as places known for seclusion, wild animals, and access to natural water sources, caves, etc. These points of passage, known to forest monks, mark the routes taken in nomad territory for seasonal ascetic wandering; that is, the “political form of space” produced by and associated with the modern state (Lefebvre in

Brenner and Elden 2009, p. 362). These

dhutaṅga sites are “in-between”, becoming-spaces; a reverse of the ordered sedentary life extolled by the state. Their radical lines of flight then became political non-place zones—contesting state territorial control including, for instance, regulated new tourist sites in national parks. Because of their sometimes-haphazard movement, the state had to regulate the wanderers and fix these unruly flows into arborescent schema in a Deleuzian biological metaphor of tree/trunk/root arrangement (and during the twentieth century centralising reforms, following the vertical ordered lines of the civil hierarchy, including a system of status rank).

A means of regulating the wanderers was through compulsory accreditation for all Buddhist monks and a bureaucratic structure of administration. Religious nomads were always a potential menace to the centre-nation because of their potential charismatic authority across the socially and politically unstable periphery. From his fieldwork in the 1970s,

Stanley Tambiah (

1978, p. 388) also noted the problem that wandering monks without proper monastic identification papers (

bai sutthi) could readily be considered as subversives, while real insurgents in the guise of wandering monks could easily wander the countryside at this time. In a sense, both shared in the same political ecology and ideology of fear in the politically termed “red areas” (

khet sii-daeng), located in the

maquis; the interstitial smooth spaces located in the far provinces.

The wandering monks in Thailand’s early twentieth century frontier were also potential sources of anarchic danger similar to regional charismatic millenarian movements moving back and forth at the margins of the state. However, millenarian movements (as in the

phuu mii-bun revolts, which have been well documented for the margins and interstices in Thailand:

Ishii 1975;

Keyes 1977;

Murdoch 1974;

Collins 1998) emanated from the particular social transitions and a new socius in the far provinces; in most cases led by the utopian imaginings of dispossessed (traditional) local leaders.

The wandering monks were, in a sense, interstitial rhizomatic itinerants moving about in the frontier, including sharing marginal space in the uplands of the lower segments of the Southeast Asian Massif (

Michaud 1997); or “Zomia” (

van Schendel 2002;

Scott 2009) inhabited by various ethno-linguistic minorities. These minorities lived within the codings of the dominant (major) national language, consolidating around the totems of nationhood, the vocabularies of its canons and traditions, and so on (

Alliez and Goffey 2011, p. 10). These sites of movement are the forbidden and illicit zones where human actors constitute the interstices, its zone and line. In its disciplinary technology, the state therefore attempted to encourage (religious) wanderers to become sedentary, emplacing them in its ordered space (

Dreyfus and Rabinow 1983, p. 155). However, these monks resisted normalization and the coercive attempts to bring them into closed, state-regulated monasteries. The state and its instrumentalities wanted complete control over its frontier, the location of the various routes and temporary reclusive sites of the wanderers. There are many tales recorded of the confrontation with state apparatuses, which emphasize exclusion, separation, and spatial distancing as wanderers passed through human settlements, villages, and towns.

The modern state was concerned with the consolidation of the frontier during the period of regional insurgency in the 1960s and 1970s especially with the surveying of routes emanating from centre-nation and in the normalizing of frontier space of zones and lines. However, as

de Certeau (

1984, p. 97) notes, a preoccupation with place-making misses what was considered so significant for the nomads; simply the act itself of passing through. It was the act of passing through villages in remote communities that created apprehension of people in small hamlets. The necessity of collecting food alms (Pali:

pindapata) for the religious nomads was not without is challenges. At times trepidation was even turned into hostility in the volatile countryside undergoing administrative and religious regulation from the centre-nation as wanderers were chased out of villages. Both rural communities and the local state-sanctioned monks sometimes perceived the ascetic wanderers as a risk to the domesticated order of the (civilised) sedentary farming village. Ironically, later on, after reterritorialisation, as the centre-nation incorporated the reform ordained wanderers into its normative religious apparatus, they were seen by many remote communities as “frontiersmen” for the state, in extending the skein of the nation-state over the frontier provinces.

It is the continuous movement of these nomadic monks that is so important. As mentioned earlier, the state attempted at the turn of the century, but especially later in Article 45 of the Sangha Act of 1941, to institute controls or striations on monastic wandering through the implementation of new regulations. This required non-domiciled monks to register at recognized and properly sanctified monasteries (

J. Taylor 1993, p. 99). The location of the much sought-after charismatic power of forest monks (whether in the north, south, or northeast of the country) is situated in the ambiguous zones, spaces where the traces of power flow in transition between nomadic dynamics (rhizome as open multiplicity) and sedentary (arborescent) structures.

9. Concluding Comments

The wandering monks in their expressive religious nomad science articulated resistance with the state in passive and internalized ways, such as turning away from consuming machinic pleasures and hankering of the world (desiring-production).

26 An end, but also a new opening. Wandering forest monks, as recluses, were intuitive mind-body warriors (in the sense of a politico-religious war machine), resisting the molar organisations of the state and in the external desires attributed to the materialist world and its capitalist axiomatic. This may be seen to delve deep into the most basic human predispositions and habits, to the unconscious itself.

As we noted briefly in case studies of religious itinerants in the borderlands of Thailand, the charismatic power of the wanderers was gained by their free movement; their persistence in occupying marginal spaces as counter-sites, in the exteriority of the conventional world of desires. They would leave behind hearth and kindred, even resisting the pleasures of settlement in permanent monasteries until, in more recent times after domestication, they were forced by the modern state to carry identity cards and take on semi-permanent monastic abode. These monasteries were royal sanctified residences under the control of the state’s administrative apparatuses who oversaw and regulated religious nomad science and their technologies of wandering, in the north and northeast of Thailand.

As discussed, there is also a normative reference point where religious nomadism is located at the endo-exteriorities as a minor science even if it is captured by the centre. This is why religious practices are differentiated along many lines. In the hybrid-Sanskrit/Pali canon, there are many verses of aspiration (and in orthodox non-canonical texts) that epitomize a religio-rhizomatic sentiment as the psycho-social space in which movements or processes of liberation of consciousness are possible. This indicates that religious ascetic wanderers in the orthodox reform sect were both interior to the polis, though also inhabiting the internalised exteriorities or margins of the state. As for instance, the normative Sutta-Nipāta (Pali Canon) lauds wandering and the wandering Buddhist mystics or ascetics using the simile of the lone wandering “rhinoceros”, creating its own liberating minor lines across the nomos (as nomadic law). Similarly, in the Thera-Gāthā on the eremitic early arahant Tālaputa Thera.

These similes articulate the sentiments of religious wandering; as a doctrinal discourse and as a new (pure) plane of immanence, this implies internal work, annihilating enslavement of bodily passions, mental detachment from the conventional world, and eventually for the spiritual virtuoso to attain the absolute non-productive (unconditioned) absolute in

non-being. It is in this internal experience that all spatial flows pass through ceaselessly in all directions to the unconditioned and the unformed.

27 This leads to the pure plane of liberation gained through a nomadic science with the free (pure) intensities or nomadic singularities of the body-without-organs.