Miyun Yuanwu 密雲圓悟 (1567–1642) and His Impact on 17th-Century Buddhism

Abstract

:1. Historical Background

2. Biographical Sketch

3. The Dominance of Miyun’s Lineage

4. Beyond China

5. Conclusions

Funding

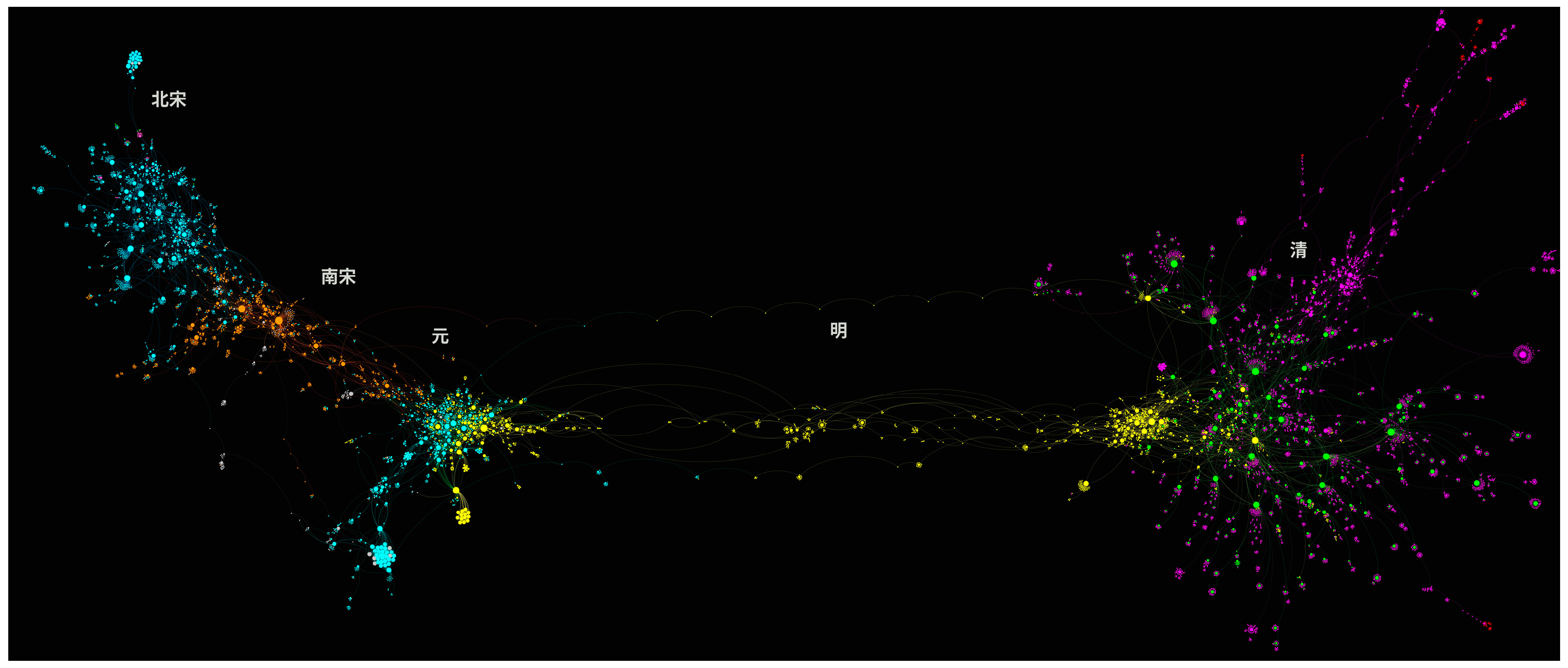

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Available at https://github.com/mbingenheimer/ChineseBuddhism_SNA. Accessed on 26 January 2023. The dataset has been described in detail in Bingenheimer (2021). In short the complete dataset contains information about c.18,000 actors, which are connected by c. 32,000 links. The main component spans the period from c. 250 CE to 1900 CE. The dataset is a combination of data extracted from collections of biographical literature and the lineage information contained in the Dharma Drum Buddhist Person Authority Database (https://authority.dila.edu.tw/person/. Accessed on 26 January 2023). Studies based on earlier versions of the data are Bingenheimer (2018, 2020). |

| 2 | There remained residual interest in Buddhism both Chinese and Tibetan among the eunuch faction and the female members of the court. Neither association, of course, worked in its favor in the eyes of the Confucian elite. |

| 3 | In the context of Chinese religion as a whole, Vincent Goossaert speaks of Cheng-Zhu Neo-Confucianism as a “radicalisation” of Confucianism (Goossaert 2000, pp. 87–103), that shifted the equilibrium between the “three teachings”. |

| 4 | On the influence of Buddhism on Wang Yangming as well on his own impact on syncretistic thinkers in the late Ming see Kubota ([1931] 1986) and the examples in Araki (1972). In English, on the Buddhist influence on Lu-Wang Neo-Confucianism see Chan (1962) and Ivanhoe (2009, pp. 3–14), on Wang Yangming’s impact on late Ming Buddhists see Chu (2010). |

| 5 | Zhang (2020, p. 36). Zhang’s (2010) Ph.D. thesis, on which the book is based, was aptly titled “A Fragile Revival”. |

| 6 | The term “late Ming revival” is widely used in English, e.g., in the standard account of Ming Buddhism by Yü (1998, p. 927). Conceptualizing Buddhist history in terms of decline(s) and revival(s) is common in both emic and etic historiography of Buddhism. Our dataset, in a way, corroborates the standard narrative of a decline in the mid-Ming, but it should be remembered that it focuses on monastic Buddhism and does not well capture the vitality of lay Buddhist movements or the influence of Buddhism on Chinese folk-religion. |

| 7 | In English we have a number of monographs regarding the late Ming—early Qing revival of Confucian interest in Buddhism (e.g., Hsu 1979; Yü 1981; Brook 1993; Eichman 2016; Zhang 2020), in Japanese especially the works of Araki Kengo (e.g., Araki 1995), in Chinese Liao Chaoheng (e.g., Liao 2010, 2014), has contributed important studies. |

| 8 | All network visualizations in this paper were primarily produced in Gephi (0.9.3), with Force Atlas 2 as the basic layout algorithm. The Gephi output was adjusted and annotated with tools including Nomacs, gThumb, and Krita. As a consequence of how links are defined (as contact between contemporaries), many layout algorithms align the nodes in this dataset roughly along a timeline. For all figures in this paper, I have rotated the images for this rough, imaginary timeline to run from left to right. |

| 9 | For this period, Wu (2008, p. 23) speaks of a “lacuna in historical records about Buddhist activities. Few Buddhist histories had been written and official records seldom mentioned Buddhist institutions”. Whereas the network dataset reflects mainly the dearth of biographical information, the decline can also be seen in temple construction and repair (Eberhard 1964). The much smaller thinned out region in the Southern Song is probably due to the fact that much of the country was lost to the Jin and there is less information on (Liao, Tangut, and) Jin Buddhism in the sources of the dataset (biographies and authority database lineage data). |

| 10 | E.g., Yü (1998, p. 931), Ren (2009, p. 276), and in the Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism (e.g., sub voc. Ouyi Zhixu). This particular grouping, also called 晚明四大高僧, seems rather recent. I have yet to find a pre-20th century source for it. The term “three great masters” 三大師, on the other hand, was at times used to group Zhuhong, Zibo, and Hanshan, by 17th century writers such as Juelang Daosheng 覺浪道盛 (1593–1659) (CBETA 2021.Q4, J34, no. B311, p. 714c25), Qian Qianyi 錢謙益 (1582–1664) (CBETA 2021.Q4, X13, no. 287, p. 515c12), or Xu Fang 徐芳 (fl. 1670) (CBETA 2021.Q4, X86, no. 1608, p. 614a10-11). |

| 11 | To mention only the monographic studies: Yü (1981) on Zhuhong; Hsu (1979), Yen (2004), Epstein (2006), Jiang (2006), and Hiu (2014) on Hanshan; Cleary (1985, 1989), Fan (2001), and Gault (2003) on Zibo; S. Shi (1987) and McGuire (2014) on Ouyi. For the interaction of these leaders with their literati supporters see Eichman (2016). |

| 12 | There seems no standard practice in modern academic writing about which name part to use when abbreviating the name of Chan monks. Most writers seem to prefer Zhuhong over Yunqi, but in other cases the tendency is to abbreviate to the alias rather than the dharma name, i.e., Hanshan instead of Deqing (Hiu 2014), Zibo rather than Zhenke (Cleary 1989; Huang 2018), or Ouyi rather than Zhixu (McGuire 2014). It could be argued that the Dharma name is to be preferred as the legal name, which is relatively fixed, compared to several possible aliases. Using an alias, however, conforms better with historical practice, which eschews the use of the dharma name, which in the context of the Chan lineage discourse often functioned as a de facto taboo name. Thus, in cases where monastic names are abbreviated to three characters, usually the first character of the Dharma name is omitted, while the alias is kept intact. In general, the alias is preferred in book titles as well, thus “Miyun”—not “Yuanwu”—in the titles of his “Collected Sayings” (s.b., CBETA/L1640 and CBETA/JA158). Following this argument I generally use the alias for all monks, with the exception of Yunqi Zhuhong, who in Western literature is by now widely known under his Dharma name Zhuhong (instead of the toponym “Yunqi” or the alias “Lianchi” 蓮池). |

| 13 | Here and below such IDs refer to the Dharma Drum Buddhist Studies Person Authority Database (https://authority.dila.edu.tw/person/) (26 January 2023). |

| 14 | Miaofeng Fudeng’s role has been recognized in recent scholarship only by Zhang (2020, pp. 184–96), who also remarks that Miaofeng “sank into oblivion after death”. Had a network perspective on Buddhist history been available earlier, Miaofeng might not have been forgotten so easily. His prominent position (see Figure 2) is obvious in this approach. |

| 15 | Qian ([1698] 1983, p. 698). The biographies, originally part of the Liechao shiji 列朝詩集 anthology were extracted and published by Qian Lucan 錢陸燦 in 1698. On Qian Qianyi’s views regarding Buddhism and how they influenced the inclusion of poet monks in the Liechao shiji see Liao (2019). |

| 16 | More recently, Chao-heng Liao has identified Hong’en as being underestimated when compared with Zhuhong and the others (Liao 2014, pp. 37, 79). Hong’en and Hanshan were friends, as were Hanshan and Zibo (Eichman 2018, p. 137). |

| 17 | A short example for how this teaching style looked like in the early 17th century: “A monk entered [his room for personal instruction]. The teacher [Miyun] said: ‘What are you doing here?’ The monk said: ‘I grind [the beans] for Tofu’. The teacher said: ‘Who are you grinding them for?’ The monk said: ‘I am grinding them for you’. The teacher said: ‘You eat your own meals, why [do you say] you are grinding for me?’ The monk said: ‘If I don’t grind for your sake, no one will grind for my sake.’ The master hit him and the monk left the room”. (CBETA 2022.Q1, L154, no. 1640, pp. 478b15–479a3). |

| 18 | See Noguchi (1985, pp. 57–58) for some references to criticism of Miyun’s style of Chan by Zibo, Hanshan and others. |

| 19 | For the latter see for instance Hanshan’s exhortation to study the Confucian and Daoist classics (translated in Hiu 2014, p. 379 ff). Their inclusivism did not extend to Christianity, however, against which Zhuhong, Ouyi as well as Miyun and his students wrote polemics (Gernet 1982). |

| 20 | See the translated texts by Miyun and Feiyin Tongrong in Kern (1992, pp. 93–193) and the discussion of their content by Nishimura (2022). |

| 21 | |

| 22 | Wu (2008, pp. 105–7) suggests a development in three different stages: First, the Wanli “late Ming revival” around Zhuhong, Hanshan and Zibo. Second, the dominance of Chan lineages c. 1620–1644. A third phase, Wu suggests ranges from the beginning of the Manchu conquest to about 1733, when the Yongzheng emperor intervened in the long lasting debate between the students of Miyun Yuanwu and Hanyue Fazang. The data presented here reflects the transition of the first two stages relatively clearly, but the Manchu conquest seems to have made little difference for the network. The dominance of Miyun’s school lasted from the 1620s into the 18th century. This agrees with the periodization suggested by Yūkei Hasebe (1990, p. 89), whose third and forth phase are what in this paper is defined as the two stages in the late Ming revival (the “Wanli revival” stage and the dominance of Miyun’s school). Hasebe’s third phase, which he calls tenkan ki 転換期 “the period of transformation”, spans the Longqing and Wanli reigns (1567–1620), a fourth phase (shūha seiritsu hatten ki 宗派成立発展期 “the period of establishment and growth of lineages”) in the development of Ming and Qing Buddhism lasted, according to Hasebe, from 1621 to the end of the Qianglong reign (1795). |

| 23 | For instance in the Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism (sub voc.), or the Historical Dictionary of Chan Buddhism (Wang 2017). |

| 24 | The two competing yulu are: Muchen Daomin’s Miyun chanshi yulu 密雲禪師語錄 in 10 fascs. (CBETA/L1640), the other by Feiyin Tongrong and others: Miyun chanshi yulu 密雲禪師語錄 12 fascs. (CBETA/JA158). Titles vary slightly by edition. A detailed bibliographic study for these is still needed, but see Luo (2009) for a first assessment of the differences. The first three juan of Feiyin’s edition contain the notes that different first-hand witnesses took during Miyun’s various postings, making this an immediate source for Miyun’s teachings. For the antagonism between Muchen and Feiyin see Noguchi (1985). |

| 25 | The first monograph on this is Yuan Chen (1962). The major treatment of these controversies in English is Wu (2008), who analyses two of the major debates in depth and gives an overview of others (Wu 2008, p. 297). |

| 26 | Much work remains to be done. The best article-length treatment of Miyun’s life I found is Xu (2002). Xu includes an annalistic summary, which is based on the nianpu 年譜 contained in his two yulu (CBETA 2021.Q4, J10, no. A158, p. 75c1, CBETA 2021.Q4, L154, no. 1640, p. 569a1) and other early biographies (listed in Xu 2002, pp. 81–82). There also exists a somewhat helpful MA thesis (Luo 2009). The most comprehensive history of Chinese Buddhism, Lai (2010) ’s Zhongguo fojiao tongshi, which often includes important figures not mentioned elsewhere, does not do justice to the importance of Miyun and his school. In Vol. 12 (Ming Dynasty) Miyun is mentioned several times in passim as part of the (generally negative) assessment of late Ming Chan, but his contribution is never discussed at length. |

| 27 | For Miyun’s own testimony regarding that transition see CBETA 2021.Q4, J10, no. A158, p. 76b18-27. |

| 28 | For Zhuhong see Yü (1981, p. 11), for Zhenqing see Bingenheimer (2022), for Hanshan see Hsu (1979, p. 62). |

| 29 | For the circumstances of Zibo’s death after torture see Zhang (2020, pp. 171–84). |

| 30 | The “stick and shout” style of instruction was carried over to at least some non-monastics as well. Here is a story involving a guest of Tao Wangling: “When Miyun stayed at Houshan, a man of high rank came to his hut and saw him reading the Analects and Menzius. The gentleman asked: ‘What are you reading?’ Miyun showed him. The gentleman said: ‘I thought that wasn’t your type’s cup of tea.’ The master hit him and the gentleman got angry. Just then Tao Wangling arrived and scolded him saying: ‘The monk gave you a view of the Buddha’s teaching. Why are you angry?’ The gentleman respectfully apologized and left”. (CBETA 2022.Q1, J10, no. A158, p. 78c19-23). |

| 31 | |

| 32 | A certain toughness in Miyun’s attitude appears even here: “When his father lay on his death bed, the teacher went to see him. His father said: ‘May the monk save me.’ The teacher said: ‘When a father and a son climb a mountain, each must do so under their own effort.’ His father said: ‘Because of you I have heard about the great matter, how could their be any regrets for me?’ Two days later he passed away”. (CBETA 2022.Q1, J10, no. A158, p. 80b8-10). |

| 33 | See the table in Xu (2002, p. 66). |

| 34 | CBETA 2022.Q1, J10, no. A158, p. 81b21 and 82a26. |

| 35 | |

| 36 | This list of Miyun’s dharma heirs appears in the second, more inclusive, yulu by Feiyin Tongrong (CBETA 2022.Q1, J10, no. A158, p. 71b1-5). A thirteenth dharma heir, the layman Huang Yuqi 黃毓祺 (A003978), is mentioned in other works (e.g., CBETA 2022.Q1, X84, no. 1582, p. 401a16). A relative increase in dharma heirs in the two generations following Miyun was already noticed by Wu (2002, pp. 11–12) when analyzing Hasebe Yūkei’s data. A contemporary Linji Chan master, Yuanhu Miaoyong 鴛湖妙用 (1587–1642) had only three dharma heirs. However, one Linji master confirmed even more students: Tiebi Huiji 鐵壁慧機 (1603–1668) had more than twenty dharma heirs (CBETA 2022.Q1, X84, no. 1582, p. 390a21), including at least one nun, and several lay-followers. Most of Tiebi’s dharma heirs, however, did not in turn produce further heirs. The relationship between Tiebi’s and Miyun’s group deserves further study. |

| 37 | The inscription for the stupa of his robe mentions that Miyun’s community comprised a thousand monks already when he presided over the Jinsu temple, and several thousand in his later years at Tiantong (CBETA 2022.Q1, J10, no. A158, p. 73b18-19). Similar statements in the nianpu (82a26, 84b6) corroborate that his monastic community was very large indeed. |

| 38 | Not surprisingly, Miyun’s lineage is remembered as an important part of Tiantong’s history on the temple’s website (http://www.nbttcs.org/intro/2.html: accessed on 26 January 2023). |

| 39 | Obviously, some of these had various different hao and zi. IDs according to the Dharma Drum Buddhist Studies Person Authority Database (https://authority.dila.edu.tw/person/, accessed on 26 January 2023). |

| 40 | These are not all dharma heirs, but all people (lay and monastic) which are mentioned in sources as having studied with the person. The count is again derived from the Dharma Drum Buddhist Studies Person Authority Database. |

| 41 | CBETA 2022.Q1, X72, no. 1444, p. 840b21-22. Zhanran’s dharma heirs were Mingxue 明雪 (34 students), Mingyu 明盂 (26 students), Mingfang明方 (19 students), Mingfu 明澓 (10 students), Minghuai 明懷 (3 students), Mingyou 明有 (1 student). Again “student” here does not equal dharma heir. |

| 42 | The Kaiyuan temples were established nationwide and existed often for centuries, whereas the “five mountains and ten monasteries” were a rather regional and relatively short-lived formation. |

| 43 | |

| 44 | The story has been told in detail by Wu (2008, chps. 4–6). See also Lian (1996) for the relationship between Hanyue and Miyun, and J. Shi (2000) for a close examination of Hanyue’s doctrinal ideas regarding Chan, which were the origin of the dispute. Huang (2018) clarifies how important textual learning was for Hanyue. |

| 45 | Apart from Hanyue’s well known Wuzong yuan 五宗原 (1628), it was Hanyue’s teaching of the Zhizheng zhuan 智證傳 a commentarial text by Juefan Huihong 覺範慧洪 (1071–1128) that was disliked by Miyun and his dharma brothers. Hanyue’s commentary on the Zhizheng zhuan was only recently rediscovered (Huang 2018). On Hanyue’s Sanfeng school see also Lian (1996). |

| 46 | |

| 47 | |

| 48 | Muchen Daomin’s encounter with the Shunzhi emperor was recorded (by Muchen’s student Zhenpu 真樸) in the fascinating Hongjue Min chanshi beiyou ji 弘覺忞禪師北遊集 (CBETA/JB 180). Muchen stayed at court almost eight months. The 北遊集 is the longest and most intimate record of conversations between a ruler and a Buddhist monk since the Milindapañha, but remains almost completely overlooked. I am not aware of any study of the text. Shunzhi’s encounter with Muchen, was a factor in Shunzhi’s devotion to Chan Buddhism after 1659. This disappointed the Jesuit missionary Adam Schall von Bell (1591–1666) who had long enjoyed Shunzhi’s confidence and had hoped the emperor would eventually convert to Christianity. In that sense, too, Miyun’s debate and competition with Christian missionaries continued through his student. |

| 49 | |

| 50 | Not much is known about Kuangyuan; his short entry in the Wudeng quanshu 五燈全書 consists mainly of encounter dialog fragments (CBETA 2021.Q4, X82, no. 1571, p. 374b8-c10). |

| 51 | Yongge Chen (2007, p. 18). Noguchi (1986, pp. 165–70) discusses some contemporary criticism to Miyun’s over-reliance on “beating and shouting”. |

| 52 | This is not to say that evidential textual scholarship played no role in the debates of the 17th century (see Wu 2008, pp. 194–95). On use of historical evidence by Buddhist historiographers in general see also Kieschnick (2022, esp. chp. 2 and 5). |

References

- Araki, Kengo 荒牧見俊. 1972. Mindai shisō kenkyū—Mindai ni okeru jukyō to bukkyō no kōryū 明代思想研究 明代における儒教と仏教の交流. Tokyo: Sōbunsha 創文社. [Google Scholar]

- Araki, Kengo 荒牧見俊. 1995. Chūgoku shingaku no kodō to bukkyō 中国心学の鼓動と仏教. Tokyo: Chūgoku shoten 中国書店. [Google Scholar]

- Bingenheimer, Marcus. 2018. Who was ‘Central’ for Chinese Buddhist History?—A Social Network Approach. International Journal of Buddhist Thought and Culture 28: 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingenheimer, Marcus. 2020. On the Use of Historical Social Network Analysis in the Study of Chinese Buddhism: The Case of Dao’an, Huiyuan, and Kumārajīva. Journal of the Japanese Association for Digital Humanities 5: 84–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingenheimer, Marcus. 2021. The Historical Social Network of Chinese Buddhism. Journal of Historical Network Research 5: 155–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bingenheimer, Marcus. 2022. Monastic biography in the Ming and Qing: The case of Shi Zhenqing 釋真清 (1537–1593). Journal of Chinese Buddhist Studies 35: 59–107. [Google Scholar]

- Brook, Timothy. 1993. Praying for Power—Buddhism and the Formation of Gentry Society in Late-Ming China. Cambridge and London: Council on East Asian Studies Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Wing-tsit. 1962. How Buddhistic is Wang Yang-ming? Philosophy East and West 12: 203–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Ya-wen 張雅雯. 2022. Zhaoshi zhen gu—Cong ‘Mingbaianji’ lun Jiqi Hongchu zhi Chanxue sixiang yu chuancheng 〈趙氏真孤──從〈明白菴記〉論繼起弘儲之禪學思想與傳承〉(The Orphan of Zhao: A Study of Chan Master Jiqi Hongchu’s Thought and its Derivation through his “Mingbai an ji”). Foguang xuebao 佛光學報 8: 145–99. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yongge 陈永革. 2007. Wanming fojiao sixiang yanjiu 晚明佛教思想研究. Beijing: Zongjiao wenhua 宗教文化. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yuan 陳垣. 1962. Qingchu sengzheng ji 清初僧諍記. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju中華書局. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, William. 2010. The Timing of the Yogācāra resurgence in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1643). Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 33: 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary, Jonathan Christopher. 1985. Zibo Zhenke—A Buddhist Leader of Late Ming China. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary, Jonathan Christopher. 1989. Zibo—The Last Great Zen Master of China. Berkeley: AHP Paperbacks. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, Kenneth, and Zhenman Zheng. 2010. Ritual Alliances of the Putian Plains. 2 vols. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard, Wolfram. 1964. Temple Building Activities in Medieval and Modern China. Monumenta Serica 23: 264–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichman, Jennifer. 2016. A Late Sixteenth-Century Chinese Buddhist Fellowship: Spiritual Ambitions, Intellectual Debates, and Epistolary Connection. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Eichman, Jennifer. 2018. Buddhist Historiography: A Tale Of Deception in A Seminal Late Ming Buddhist Letter. Journal of Chinese Religions 46: 123–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, Shari Ruei-hua. 2006. Boundaries of the Dao: Hanshan Deqing’s (1546–1623) Buddhist commentary on the ‘Zhuangzi’. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Jialing 范佳玲. 2001. Zibo dashi shengping ji qi sixiang yanjiu 紫柏大師生平及其思想研究. Taipei: Fagu wenhua 法鼓文化. [Google Scholar]

- Gault, Sebastian. 2003. Der Verschleierte Geist—Zen-Betrachtungen Des Chinesischen Mönchs-Philosophen Zibo Zhenke. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Gernet, Jacques. 1982. Chine et christianisme: Action et réaction. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Goossaert, Vincent. 2000. Dans les temples de la Chine. Paris: Albin Michel. [Google Scholar]

- Hasebe, Yūkei 長谷部幽蹊. 1990. Min Shin Bukkyō no Seikaku o kangaeru 明清仏教の性格を考える. Zen kenkyūsho kiyō 禅研究所紀要 18: 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hiu, Yunyan. 2014. La pensée de Hanshan Deqing (1546–1623): Une lecture bouddhiste des textes confucéens et taoïstes. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales—INALCO, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Sung-peng. 1979. A Buddhist Leader in Ming China: The Life and Thought of Han-Shan Te-ch’ing. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Yi-hsun. 2018. Chan Master Hanyue’s Attitude toward Sutra Teachings in the Ming. Journal of the Oxford Center for Buddhist Studies 15: 28–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, Shudō 石井修道. 1975. Minmatsu Shinsho no Tendōsan to Mitsuun Engo 明末清初の天童山と密雲円悟. Komazawa daigaku bukkyōgaku ronshū 駒澤大学仏教学部論集 6: 78–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanhoe, Philip J. 2009. Readings from the Lu-Wang School of Neo-Confucianism. Cambridge: Hackett. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Canteng 江燦騰. 2006. Wan Ming fojiao gaige shi 晚明佛教改革史. Guilin: Guangxi shifan daxue chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, John. 2007. Problems in the comparison of Korean and Chinese Buddhism: From the 16th to the 19th century. In Korean Buddhism in East Asian Perspectives. Edited by Geumgang Center for Buddhist Studies. Seoul: Jimoondang, pp. 119–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, Iso. 1992. Buddhistische Kritik am Christentum im China des 17. Jahrhunderts. Frankfurt: Peter Lang (Swiss Asian Studies). [Google Scholar]

- Kieschnick, John. 2022. Buddhist Historiography in China. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kubota, Ryūon 久保田量遠. 1986. Chūgoku Ju Dō Butsu sankyō shiron 中国儒道佛三教史論. Tokyo: Kokusho. First published 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Yonghai 賴永海, ed. 2010. Zhongguo fojiao tongshi 中國佛教通史. 15 vols. Nanjing: Jiangsu renmin 江苏人民. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, Ruizhi 連瑞枝. 1996. Hanyue Fazang yu wanming sanfeng zongpai de jianli 漢⽉法藏(1573–1635)與晚明三峰宗派的建⽴. Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal中華佛學學報 9: 167–208. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Chao-heng 廖肇亨. 2010. Zhongyi puti—Wanming qingchu kongmen yimin ji qi jieyi lunshu tanxi 忠義菩提:晚明清初空門遺民及其節義論述探析. Taipei: Academia Sinica. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Chao-heng 廖肇亨. 2014. Julang huilan—Mingqing fomen renwu junxiang ji qi yiwen 巨浪迴瀾:明清佛門人物群像及其藝文. Taipei: Fagu wenhua 法鼓文化. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Chao-heng 廖肇亨. 2019. Qian Qianyi sengshiguan de zai xingsi—Cong Liechaoshiji xuanping shiseng tanqi 錢謙益僧詩史觀的再省思—從《列朝詩集》選評詩僧談起. Hanxue Yanjiu (Chinese Studies) 37: 239–73. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Yiwen 罗谊文. 2009. Mingmo chanseng miyun yuanwu yanjiu 明末禪僧密雲圆悟研究. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, Berverly Foulks. 2014. Living Karma—The Religious Practices of Ouyi Zhixu. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura, Ryō. 2022. The Void and God: Chinese Criticisms of Christianity in Late-Ming Buddhism. Journal of Chinese Buddhist Studies 中華佛學學報 35: 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi, Yoshitaka 野口善敬. 1985. Hiin Tsūyō no Rinzaizen to sono zasetsu: Kichin Dōmin to no tairitsu o megutte 費隠通容の臨済禅とその挫折: 木陳道忞との対立を巡って. Zengaku kenkyū 禅学研究 64: 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi, Yoshitaka 野口善敬. 1986. Minmatsu ni okeru ‘shujinkō’ ronsō: Mitsuun Engo no rinzaishu no seikaku o megutte 明末に於ける「主人公」論争—密雲円悟の臨済禅の性格を巡って (Controversy on the ‘Zhu Ren Gong’ (主人公) in the End of Ming Dynasty—On the Character of密雲円悟 Zen). Tetsugaku nenpō 哲學年報 45: 149–82. [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi, Yoshitaka 野口善敬. 2011. Minmatsu shinsho ni okeru Tendōji no jūji ni tsuite: Mitsuun Engo no kōkei ni tsuite 明末清初における天童寺の住持について: 密雲円悟の後継をめぐって. Zengaku kenkyū 89: 17–45. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Qianyi 錢謙益. 1983. Liechao shiji xiaozhuan 列朝詩集小傳. Shanghai: Shanghai guji 上海古籍出版社. First published 1698. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Yimin 任宜敏. 2009. Zhongguo fojiaoshi—Mingdai 中国佛教史 明代 [History of Chinese Buddhism—The Ming Dynasty]. Beijing: Renmin 人民出版社. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Jianyi 釋見一. 2000. Hanyue Fazang zhi chanfa yanjiu 漢月法藏之禪法研究. Taipei: Fagu wenhua 法鼓文化. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Shengyan 釋聖嚴. 1987. Mingmo zhongguo fojiao zhi yanjiu 明末中國佛教之研究. Translated by Guan Shiqian 關世謙. Taipei: Xuesheng shuju 學生書局, Translated by Shangyan. 1975. Minmatsu Chūgoku Bukkyō no kenkyū: Toku ni Chigyoku no chūshin to shite. Ph.D. thesis, Sankibo, Tokyo, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Zhici 谭志词. 2007. Qingchu guangdongji qiaoseng Yuanshao chanshi zhi yiju yuenan ji xiangguan wenti yanjiu 清初广东籍侨僧元韶禅师之移居越南及相关问题研究. Overseas Chinese History Studies 华侨华人历史研究 2: 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Thich, Thien-An. 1975. Buddhism and Zen in Vietnam: In Relation to the Development of Buddhism in Asia. Los Angeles: College of Oriental School. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Youru. 2017. Historical Dictionary of Chan Buddhism. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Jiang. 2002. Orthodoxy, Controversy and the Transformation of Chan Buddhism in Seventeenth-Century China. Ph.D. thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Jiang. 2008. Enlightenment in Dispute—The Reinvention of Chan Buddhism in Seventeenth-Century China. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Jiang. 2015. Leaving for the Rising Sun—Chinese Zen Master Yinyuan and the Authenticity Crisis in Early Modern East Asia. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Yizhi 徐一智. 2002. Wanming Miyun Yuanwu chanshi (1566–1642) zhi yanjiu 晚明密雲圓悟禪師(1566–1642)之研究. Shihui 史匯 6: 59–83. [Google Scholar]

- Yen, Chun-min. 2004. Shadows and Echos of the Mind—Hanshan Deqing’s Syncretic View and Buddhist Interpretation of the Daodejing. Unpublished. Ph.D. thesis, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Yü, Chün-fang. 1981. The Renewal of Buddhism in China: Chu-hung and the Late Ming Synthesis. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yü, Chün-fang. 1998. Ming Buddhism. In The Cambridge History of China. Edited by Twichett & Mote. vol. 8, pp. 893–952. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Dewei. 2010. A Fragile Revival—Buddhism under the Political Shadow, 1522–1620. Ph.D. thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Dewei. 2020. Thriving in Crisis—Buddhism and Political Disruption in China, 1522–1620. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

| No. in Figure 4 | Name[fn39] (ID) | Dates | No. of Notable Students40 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hanyue Fazang 漢月法藏 (A003668) | 1573–1635 | 49 * |

| Wufeng Ruxue 五峰如學 (A003855) | 1585–1633 | 1 | |

| Shiche Tongsheng 石車通乘 (A016036) | 1593–1638 | 3 | |

| 4 | Feiyin Tongrong 費隱通容 (A001150) | 1593–1661 | 65 * |

| 5 | Fushi Tongxian 浮石通賢 (A012052) | 1593–1667 | 59 |

| 6 | Wanru Tongwei 萬如通微 (A012040) | 1594–1657 | 54 |

| Shiji Tongyun 石奇通雲 (A014742) | 1594–1663 | 15 | |

| 8 | Linye Tongji 林野通奇 (A012053) | 1596–1652 | 43 |

| 9 | Muchen Daomin 木陳道忞 (A001513) | 1596–1674 | 86 * |

| 10 | Poshan Haiming 破山海明 (A009652) | 1597–1666 | 90 * |

| 11 | Muyun Tongmen 牧雲通門 (A001148) | 1599–1671 | 49 |

| Chaozong Tongren 朝宗通忍 (A016164) | 1604–1648 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bingenheimer, M. Miyun Yuanwu 密雲圓悟 (1567–1642) and His Impact on 17th-Century Buddhism. Religions 2023, 14, 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14020248

Bingenheimer M. Miyun Yuanwu 密雲圓悟 (1567–1642) and His Impact on 17th-Century Buddhism. Religions. 2023; 14(2):248. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14020248

Chicago/Turabian StyleBingenheimer, Marcus. 2023. "Miyun Yuanwu 密雲圓悟 (1567–1642) and His Impact on 17th-Century Buddhism" Religions 14, no. 2: 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14020248

APA StyleBingenheimer, M. (2023). Miyun Yuanwu 密雲圓悟 (1567–1642) and His Impact on 17th-Century Buddhism. Religions, 14(2), 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14020248