1. Introduction

The aim of this paper is to define an anthropological theory of the body and disease in the Buddhist conception. To do this, I will primarily use the theoretical tools of the anthropologist Ernesto De Martino, who has reflected on the concepts of “presence” and “crisis”, constituting a real trait d’union between medical anthropology and cultural studies on asceticism. As we will see, the Buddhist conception of medicine is deeply intertwined with the history of its ascetic origin and, thus, with ideas concerning awareness and transcendence, such as the ideas of presence and absence, and that of the ancient healer as a “magician”.

In examining the Buddhist medical tradition, there are two basic elements that can be analyzed: The first is purely historical, and it includes the parallel development of Buddhist medicine and Āyurveda in connection with the ascetic traditions of pre-Indo-European India. Secondly, medical anthropology deals with the idea of illness itself, in terms of how Buddhism (in this case) conceives health and malaise in its elaborate therapeutic and curative methods, interwoven with cultural and philosophical matters. I will attempt to answer both questions, though focusing more on the second, since the history of the development of Buddhist medicine—as well as its connection with Āyurveda and ascetic practices—is closely associated to the ideas of transcendence and consciousness, which relate to the contemplative experience described in the Pāli Canon. In this regard, recognizing the importance of the medical view of Buddhism is crucial for medical anthropology in general, since “the very earliest reference in Indian literature to a form of medicine that is unmistakably forerunner of āyurveda is found in the teachings of the Buddha” (

Wujastyk 2012, p. 31).

In this introductory section, I provide a brief overview of what we know so far about the conception of medicine in Buddhism. Several authors have dealt with medical matters in Buddhism from an archaeological point of view. In particular, the works of Zysk, Salguero, and Wujastyk are essential. Their studies reveal three fundamental facts: The first is that Buddhism was born together with its conception of medicine (

Zysk 2021, p. 4;

Salguero 2022, p. 19). The ideas of health and disease are not secondary to the birth of Buddhism; they are an integral part of it, and during its development Buddhism continued to maintain a peculiar relationship with medicine, usually providing medical education to its monks (

Crosby 2020, p. 146;

Wujastyk 2022b, p. 402). The second fact is that Buddhism testifies to a medical tradition from the earliest sources (

Salguero 2015, p. 37). In particular, the Pāli Canon is the subject of this investigation. Third, Buddhism and traditional Indian medicine (

āyurveda) are sciences that are arguably derived from a common root (

Zysk 1995, pp. 146–49).

Today, it is commonly asserted that the Indian culture inherited two distinct medical traditions: One is that carried by the Vedic knowledge and preserved in its literature. The other, probably of non-Indo-Aryan origin (although this theory is still controversial and difficult to prove, cfr.,

Wujastyk 2022b, p. 401), is a medical tradition linked to asceticism and traditional knowledge of phytotherapeutic pharmacopoeia and empirical observations of the body. This distinction between an empirical–rational type of medicine and a more magical–religious one is a distinction that finds clear definition in the works of Zysk and that is also corroborated by other scholars, such as Wujastyk and Bronkhorst (

Divino 2022). However, these two radically different views on the body and medicine end up clashing and partly mixing in the course of Indian cultural history. The āyurvedic medicine is surely not derived from Vedic medical traditions (

Wujastyk 2022b, p. 401). Nevertheless, when the opposition of the Buddhist medical tradition (and the proto-āyurvedic tradition in general) to the Vedic tradition is theorized, it is done by building an axis that divides the proto-āyurvedic empirical medicine from the Vedic medicine. This

caesura is mostly based on magical–ritual formulas. However, the empirical foundation of Buddhist medicine does not necessarily indicate an absence of magical characteristics, and indeed I would like to try to argue that it is still possible to build a rational concept of medicine even when starting from a magical foundation, which is the theory of

presence (see

Beneduce 2019, p. 218).

From the pharmacological point of view, Buddhism has preferentially used phytotherapeutic remedies (

Salguero 2015, p. 43). Moreover, the use of herbal medicine is mentioned in yoga treatises, although it is not significantly developed (

Birch 2018, p. 35). Nevertheless, the use of these remedies has always been linked to the proper understanding of Buddhist teachings. Without meditation, the effectiveness of the medication is uncertain. It could be argued that the actual activation of the healing power of a drug depends on the patient and doctor’s participation in the Buddhist doctrine (AN 9.34). The absence of illness is fundamental to understanding the teachings of the Buddha (AN 5.78). The Buddha himself affirms that he constantly risks falling ill, and for this reason body care is also essential (AN 3.36).

In the Pāli Canon, the figure of a physician also often appears: Jīvaka Komārabhacca, admired for his incredible healing skills to the point that his fame was “the cause of an unmanageable upsurge in the number of sick candidates seeking ordination” (

Salguero 2022, p. 23). Numerous episodes in the Pāli Canon describe people cured by Jīvaka’s therapies and are an important source for the reconstruction of early Buddhist medicine (relevant episodes of this kind were analyzed by

Zysk (

1982)). Jīvaka is described as devoted to the figure of the Buddha, although it is difficult to sustain that he was a “Buddhist”. Nevertheless, he is a very important figure (

Crosby 2020, p. 146), famous for a well-known episode in which he cured the Buddha himself (

Zysk 1995, p. 147). As appears evident now, Buddhism has consistently placed a heavy emphasis on the practice of medicine, from its ancient origins through to the present day. Such a strong medical background cannot be solely attributed to the Buddhist doctrine of suffering and liberation. Rather, it appears to be a result of a more complex system—one that includes beliefs about suffering, as well as cosmological and psychological ideas that stem from the religion’s ascetic roots and its association with what Ernesto De Martino referred to as the “World of Magic” (

mondo magico). In this way, medicine remains an integral part of the Buddhist tradition to this day.

“Evidence for the beginnings of a systematic science of medicine in India appears first in the literature of the earliest Buddhists, with many medical tales being recounted in the Tripiṭaka. The Buddha instructed his monks to care for each other in sickness, since they had abandoned the social structures which would have provided them with treatment if they had not left their families to become monks.”

It is impossible to provide an exhaustive list here of the medical references found in the Pāli Canon, as they are many and varied. Consequently, this paper presents an overview of the main ideas. Most references to medicine in the Pāli Canon appear to be focused around the concept of the body and, consequently, sickness. Despite this emphasis on the body, it is important to note that ancient Buddhism acknowledges two distinct layers of medical discourse. These layers are closely intertwined, but they also differ in terms of their eschatological implications. This distinction is made through the use of two terms:

dukkha and

roga. Starting with the latter, the term

roga is clearly used to indicate a dysfunction in medical terms; it can refer to both cognitive diseases (

cetasika roga) and organic–somatic diseases (

kāyika roga,

kāyaroga). In both cases, these are factors that can be healed with therapy or medical treatment. What medicine alone cannot heal is existential discomfort (

dukkha), the cure for which also coincides with the disappearance of every

roga (see AN 4.157 and 10.60). This idea of two distinct but interconnected medical planes testifies to a conception of contemplative transcendence, or meditation, as a kind of

medicīna magnā. The same claim to cure any possible disease is shared also by nearly all premodern yogic traditions (

Birch 2018, p. 63). In AN 10.108, the physician is described as a positive figure: “the doctor prescribes purgatives to eradicate the disease caused by disorders of bile, phlegm and air” (

tikicchakā, bhikkhave, virecanaṃ denti pittasamuṭṭhānānampi ābādhānaṃpaṭighātāya, semhasamuṭṭhānānampi ābādhānaṃ paṭighātāya, vātasamuṭṭhānānampiābādhānaṃ paṭighātāya). The subsequent passages explain exactly what we have said so far—the Buddha conceives two levels of possible medicines: a worldly medicine that makes use of physical medicines, and a

medicīna ūniversālis capable of healing any ailment: “oh beggars, such medicines exist, I do not deny that. But this kind of medicine sometimes works, sometimes fails. I will teach you the noble medicine that never fails” (

atthetaṃ, bhikkhave, virecanaṃ; netaṃ natthī ti vadāmi; tañca kho etaṃ, bhikkhave, virecanaṃ sampajjatipi vipajjatipi; ahañca kho, bhikkhave, ariyaṃ virecanaṃdesessāmi). The therapy proposed by the Buddha is thus an eightfold therapy, like the eightfold path, but obtainable in the following order: right thought (

sammāsaṅkappa), right speech (

sammāvāca), right action (

sammākamma), right way of life (

sammā-

ājīvassa), right effort (

sammāvāyāma), right mindfulness (

sammāsatissa), right concentration (

sammāsamādhi), and right knowledge (

sammāñāṇa). The figure of the Buddha reconfirms this idea of the power of Buddhist medicine, being often being called “Great Physician” or “King of Physicians” (

Salguero 2022, p. 25).

In any case, the drastic division between empirical–rational and magical–religious thinking, which Zysk draws to separate Vedic medicine from Buddhist and proto-Ayurvedic medicine (

Zysk 1991, p. 21), is a rather

tranchant distinction that in my opinion presents numerous flaws. While it is certainly true that Vedic medicine has a functionality that is strictly connected to the ritual (and that it lacks an organic–holistic vision of the body), it is not equally easy to assume that Buddhist medicine draws its vision from a reflection that has nothing to do with the magical dimension. The magical dimension exists in Buddhism if we understand magic in the same way that Demartinian anthropology has described the processes of the defense of “presence”.

According to De Martino’s anthropological theory,

presence is the awareness of one’s ability to be in relation with the world and to feel connected to it and human history. Different cultural conditions can grant individuals a certain degree of

presence, while social conditions can help maintain it. When the normative orders that previously enabled an individual’s

presence in the world become disrupted, they can experience a crisis of

presence, which can also occur at the cultural (collective) level. The crisis of

presence, which is an individual’s experience of apocalypse, is closely related to both magic and medicine. These practices are developed as techniques to preserve and protect

presence during times of crisis. In other words, the emergence of a cultural order leads to the emergence of a magical–religious dimension. The norms on which society is based are recognized by De Martino himself, similarly to how Buddhism recognizes them, as ephemeral, arbitrary, and impermanent designations; it is the “economic order” that establishes a world made of “things” and “names”, related according to a certain social project (

De Martino 2019, p. 428). Things are therefore at constant risk of collapsing, revealing that all of the certainties promised by cultural society are actually illusions. Faced with this risk, society cannot allow individuals to fall into madness and disorder. Therefore, the rules on which the “world” is based are presented as absolute and indefectible, unalterable states of nature, so that people may trust them actively. Presence itself is based on this reassurance, and it feels like being part of history because it feels that its “being-there” (

Dasein) belongs to a “world”. What happens, however, is that situations occur in which that reassurance can falter. Tragedies such as death, illness, and the loss of one’s social role remind the presence of its intrinsically tragic condition; subjectivity declines, and an apocalyptic crisis rises: “communication is impossible”, one loses “the norm”, and presence “is lost” in nothingness because “the sense of living recedes and the primordial ethos of presentification and transcendence annihilates” (p. 535). Culture, according to De Martino, develops various strategies to address the risk of a crisis of presence. These strategies often involve the use of a magical–religious dispositive, such as the institution of rituals, which aim to reinforce the concept of a time outside of time and bolster the shared beliefs of a given community through the repetition of a cosmological narrative. Additionally, culture is aware of the potential for its own collapse and, therefore, creates apocalyptic visions and narratives to predict a resolution to the crisis. These may include salvation for the faithful, a divine intervention to restore order after chaos, or a cyclical return to the original time after the end of the world. Through such strategies, subjectivities are reassured, and anxiety about the end of the world is alleviated. Witnessing the death of a loved one, for example, triggers a crisis of presence that can only be managed by certain culturally codified ways of mourning, which he calls “ritual grief” (

De Martino 2021, p. 16). However, little can be done if the presence wants to cancel itself out, as in the case of madness (

follia). Madness is a form of the collapse of presence in the face of the weight of a world that is perceived as more oppressive than welcoming (

Lesce 2019, p. 182). Presence therefore “abdicates”, allowing for its own collapse. In this situation, which humans experienced at the dawn of society, De Martino believes that there is only one possible solution. The distress before the nothingness of the vanished presence, of the futile world, prompts the one who is destined to become an ascetic to venture into this nothingness in a desperate struggle. And in this risky journey, the ascetic does not discover nothingness but, rather, something, which exists in a regulated relationship with auditory “spirits”. This is the ascetic’s victory over the world; this is their “redemption” and the rising of “magic” (

De Martino 2022, p. 74;

Geisshuesler 2021, pp. 168, 183–72). Magic was born as a healing technique, and the ascetic was born as a healer of presence. To be so powerful, the ascetic must constantly live in the balance between presence and absence, learning to exercise the weakening of their own presence. The magical techniques to weaken the unitary presence do not have the aim of totally suppressing it; although the

Dasein may, in the trance-like condition, recede, weaken, and shrink, it must “be-there” enough to maintain the trance without falling into uncontrolled possession, and to adapt the activity of the “spirits” to concrete contingencies that occur in the session (

De Martino 2022, p. 92).

In this emergence of the figure of the ascetic-healer—who De Martino sometimes calls a sorcerer/magician (“stregone” or “mago”), and sometimes a shaman—the first medical knowledge is also established. Reflection leads De Martino to question the very dichotomy of healthy and sick—two interpenetrating and interdependent elements. Who does the healer have to do with? The answer, for De Martino, is with a “health in its concreteness”—that is, “in his becoming healthy beyond the risk of falling ill: in this perspective, the use of psychopathological experiences acquires a notable heuristic value”. This is mainly in reference to the phenomenon of madness, where the crisis of presence does not come, as for the ascetic, through a voluntary act of transcendence in which one is placed on the edge of being-there, but rather through a collapse, “since, in psychic illness, what is in the healthy as risk of continuously going beyond is transformed into a psychic happening characterized by not being able to go beyond this risk, and by fruitless attempts at defense and reintegration” (

De Martino 2019, pp. 196–97).

Returning to Buddhism, it must be noted that the peculiar conception of presence, asceticism, and healing that we have observed in the Pāli Canon reflects the Demartinian anthropological theory in numerous points (as showed in

Table 1), which can therefore be used to explain the development of the ancient Buddhist theory on health and disease.

Even the Buddhist ascetic, like the Demartinian shaman, is a figure who stands at the dawn of presence, at the origin of human society. For De Martino, in fact, the therapeutic power of the yogin is like that of a psychoanalyst, and it is based on the principle of regressus ad origenem that leads the subject back to the roots of their malaise (

De Martino 2019, pp. 142–43).

In a previous study, I demonstrated how the figure of the ascetic is linked to the conception of the world (

loka) standing in contrast with the origin of the world (

lokassa samudaya) in Indian society, seen as the delimitation, through the organization of knowledge, of a border—a field that separates the nascent human society of the village from the forest (

Divino 2023, pp. 4–6;

2022, pp. 276–78). The world-to-come (the village) becomes the place of social and linguistic norms, from which the ascetic flees, to seek in the forest the peace that precedes this organization in “fields of knowledge”. Buddhists share the idea of suffering (

dukkha) as intrinsic to the very order of the world (

loka); therefore, it describes the ideal ascetic as one capable of leading the world to its end (

lokanta, lokassa atthaṅgamo), and for this reason the work of ascetic transcendence coincides with the end of the world. The ascetic is a “world ender” (

lokantagū), but also a “world knower” (

lokavidū). The apocalypse of the ascetic is therefore induced by the very will to transcend presence in its value, while the psychopathological crisis of presence, which De Martino uses to describe both psychotic experiences as well as some forms of cultural manifestation codifying collective anxieties, is not driven by the will of transcendence but, rather, from a vacillation of the being-there, which is “being in the economic world” (

oikonomikós) that “manages” (

nómos) values, concepts, language, roles, and culture (the common house:

oîkos).

“The crisis of presence is to be traced back to the double face of the economic, which, while on the one hand is a positive among positives and is exposed to the undue intrusion of other positives into its sphere—i.e., it can intrude unduly into the sphere of other positives—on the other hand, it ideally constitutes the inaugural positive, which detaches culture from nature and makes possible, by this detachment, the dialectic of forms of cultural coherence. This means that to the extent that the detachment is accomplished in a relatively narrow way, it configures the experience of a becoming that passes without and against us, baleful domain of the irrational, that is, of a “blind” rush toward death.”

Further source verification is required for my anthropological theory on Buddhist medicine as an evolution of an ascetic model of transcendence from presence. In the following section, I demonstrate the common roots of Buddhist medicine and asceticism, which are also shared with traditional Indian medicine. I also explain how this common root of asceticism and Buddhist medicine can be understood in terms of the dynamics of the crisis of presence, even in the more structured Buddhist conception.

2. Early Ascetic Medical Traditions

Wujastyk asserts classical Indian medicine to be derived almost certainly from an “ascetic milieu” that “contained a sophisticated set of doctrines” (

Wujastyk 2022b, p. 403). The presence of ascetic movements antithetical to the Vedic authority has been documented since ancient times (

Squarcini 2008). However, we do not have the possibility of knowing with certainty what the epistemological characteristics of these movements were, at least until the advent of the so-called

nāstika or

avaidika traditions, i.e., Buddhism, Jainism, Cārvāka, and Ājīvika. In Buddhism in particular, we can recognize the systematization of an earlier ascetic tradition of potentially long course. Buddhists have a specific name for the figure of their ascetic:

samaṇa—a term that was arguably used primarily by Buddhists and subsequently adopted by other traditions (

Stoneman 2019, pp. 328–29). Any anthropology that wants to reconstruct the characteristics of primordial Buddhism and the origins of their medical knowledge must necessarily confront the figure of the

samaṇa as a possible ancient ascetic depositary of therapeutic knowledge that was handed down in a certain environment of highly qualified healers. The Greeks testify (

Zysk 1991, pp. 27–33) that the

samaṇas (reported in Greek as

sarmánai or

samanaíoi) were distinct from forest dwellers (

hylobioí) and physicians or healers (

iatrikoí). Providing such a distinction seems quite pedantic at a superficial glance. On closer inspection, Buddhist ascetic traditions have always included medicine as an integral part of their practice: “

śramaṇa teachers were not just rustic medicine men from the wilderness. They were active everywhere” (

Bailey and Mabbett 2003, p. 175). Their widespread action, however, must be understood as a double practice of spreading the teaching and exercise of medical practice. Buddhist medicine has always been understood as voluntary medicine, offered free of charge to the indigent (

Zysk 1991, pp. 38–49). Not to mention hospitals—facilities dedicated exclusively to the care of the sick, of which there is already mention in the Pāli Canon (

Wujastyk 2022a, pp. 5–7).

SN 36.21 describes three humors permeating the body:

vāta,

pitta, and

semhasa. These have been compared to the

tridoṣas of the āyurvedic tradition, and they are probably the exact same humors (

Zysk 1995, p. 149). The only difference is in the name of the third humor, which is most frequently reported as

kapha in āyurvedic medicine (actually, it is possible to find its synonym

śleṣman in some places). This correspondence testifies to an ancient connection between the samaṇic medical tradition and Āyurveda, and possibly a common origin. Zysk hypothesized this kind of common heritage when he recognized that samaṇic traditions prove to be the repositories of a great body of medical knowledge opposed to the traditional Vedic one: “these wanderers sought and acquired a variety of useful information of which medicine was a significant component” (ibidem).

The management of the presence passes through the body of the ascetic. Buddhism had to deal with the crisis of presence at the very beginning of its founding as a philosophy, and it grounds its four noble truths on the awareness that all is suffering (

dukkha), all is crisis. The crisis that the Buddha went through before choosing the ascetic path began precisely after the vision of death, illness, and old age—elements that De Martino would not hesitate to define as closely linked to the crisis of presence (

Wujastyk 2009, p. 197, cfr., Buddha’s “encounter with

four bodies”, i.e., “the poor, the sick, the old, and the dead”). The centrality that exists in Buddhism for the philosophy of language and the same use of linguistic metaphors in the medical field (

Crosby 2020, pp. 141–72), which is also a common habit in Āyurveda itself (

Wujastyk 2009, p. 193;

Patwardhan 2014, p. 132), is certainly attributable to the recognition of the crisis of presence as “the loss of the very possibility of constructing a world of objects, that is, of ordering the situation in a world of values” (

De Martino 2019, p. 234). Language ordinates concepts as “objects” of the world. As I explained in a previous work (

Divino 2023, p. 8), this world of objects and concepts that De Martino talks about also exists in Buddhism, declined in the form of the primitive village (

gāma), in which the dynamics of the social order begin to emerge, and in the world (

loka), in which they are in full force. The samaṇa–ascetic’s

fuga mundī behavior must therefore be understood in the context in which the world is the center of irradiation of invasive normative powers, since they are identified as the origin of suffering (

lokassa samudaya =

dukkhasamudaya). The world is also a limiting factor, as it is based on dualistic divisions (

dvayanissito,

dvayadhammamāhu). The forest (

sañña) is instead the place of perceptive unity (

araññasaññaṃ paṭicca ekattaṃ), and the passage from the village to the forest is understood as transcendence. The Buddhist cosmological and cosmogonical conception is particularly aware of this notion, presenting an incredible understanding of the primitive village and the dimension of the forest where the ascetic goes to reach enlightenment. Beyond the forest, all otherness (

araññasañña) in general seems to play a particular role in Buddhist thought, but this should not surprise us. The origin of the magical–ascetic knowledge that is the basis of primitive medicine has been already recognized in this archetypal dimension of the forest previously (

Schultes 1969;

Forrest 1982;

Anyinam 1995).

The dynamics of the village and the forest also involve the role of animals in human society. These were key turning points in the history of civilization, as they facilitated the work required to establish a complex society—most notably agriculture. In this context, the role of animals also proves to be crucial in the history of medicine, as posited by Schwabe in 1978. Schwabe contends that the history of human society is closely entwined with human–animal relations, and he proposes two main types of “man-animal cultures”:

- -

Sheep people: These cultures, related to the domestication of sheep and goats, are connected to the timing of herding and the habits of herdsmen. This type of culture emerges perhaps as a result of the alliance between humans and wolves (future dogs), allowing better control of the herd, between 12,000 and 9000 BCE.

- -

Cattle people: Probably the first form of a similar social pattern can be found in the “bull culture of Egypt”, to be followed later by the important domestication—in the Indo-European context—of the horse. Schwabe holds this culture responsible for “a factual foundation for medicine” (

Schwabe 1978, p. 10), whereas the sheep people had only “rudimentary medical skills”.

Despite this, sheep culture is still seen by Schwabe as carrying positive values, such as “gentleness, caring, compassion, responsibility, non-violence, and contemplation” (p. 11).

Animality plays a fundamental role in Buddhism, in that the animal resides in the otherness of the forest where the ascetic seeks the absolute and enlightenment, but it is also the source of their supposed medical knowledge. Signaling the ascetic’s connection to the same place as the animals, we often see this figure intersecting with animal morphology in representations. The ascetic’s body marks their otherness from the human body. Just as the dimension of the primitive village establishes an ordered society in contrast to the chaos of the forest, we can also envision the two different anthropological corporealities.

Giorgio Agamben has elaborated a theory that distinguishes bare pre-social life (

zōḗ), and which associates human beings with animality and life within the city (

bíos). The human body in the city (where rights and protections are recognized) is subject to certain conceptions and is distinct from the body that is considered non-human and capable of being killed, which is considered to have bare life. In ancient institutions, the removal of political rights (related to the

pólis, in the Greek case) corresponds to a return to the animal condition, as in the case of the

homō sacer (

Agamben 2017, pp. 74–77). Not everyone knows that Ernesto De Martino had also elaborated a very similar theory (

De Martino 1995, p. 106), speaking of mere life (

mera vita) as opposed to “economically-managed” life (

ordine economico, vita economica).

Table 2 offers a possible comparison between the theories of Agamben and De Martino with the Buddhist conception of life. Buddhism is not unaware of these discourses related to the body and the politics of the body, and it knows that the figure of the animal, with which the ascetic mixes, is fundamental.

“Almost all great ancient civilizations were built by people with a bull-cow culture. Where cattle people gained ascendency over sheep people, as they did throughout the Middle East, the sheep-based culture did not usually die out but was subordinated. Cattle cultures and grain production went together and, in such settled communities, real learning—including medical knowledge —and civilization first took root. Only in India has a major ancient cow culture survived, particularly among the Dravidians of the south but also to some extent in the north where Dravidian culture partially absorbed horseback-riding Aryan conquerors. This Indian cow-culture also retains some of the qualities presumably derived from other conquered sheep people, possibly the Munda. Thus Buddhism and Jainism, both gentle religions of the sheep-people type, probably arose as cultural revivals among the predominantly cattle-culture Indians where sheep herders were subservient and sheep raising had come to occupy an ecologically and economically marginal niche. Interestingly, these Buddhists established the first veterinary hospitals of record (the pasuciktsa built by the emperor Asoka in the third century B.C.), as the other life-revering Jain religious community of India sponsors veterinary hospitals to this day.”

The world of the Indus Valley Civilization has often been referred to as the cultural origin of traditional Indian medicine. Zysk reflects on the possibility that the evidence of ancient yogin portrayed in Harappan seals is also a demonstration of a conception about the body and medicine that was later assimilated by the Indo-Aryans (

Zysk 1991, pp. 11–3). These very ancient and supposed first yogin possess a distinctive feature: they are all theriomorphic, i.e., in transfiguration between the human and the animal.

The Vedic herdsman (

govyacchá) appears in the middle Vedic literature on two occasions: one related to the

rājasūya consecration—this rite is also shown to be very important for the purposes of Buddhist symbology (

Divino 2023, pp. 14–18)—and the other in relation to the rite of human sacrifice (

puruṣamedha). If the figure of the herdsman is important to the Vedic culture to the point of appearing symbolically in two such important rituals, this would corroborate Schwabe’s thesis of the Indo-Aryans as being an ancient sheep culture, but things are not so easy to demonstrate. Nelson finds the figure of the herdsman (

govyacchá) to be mentioned together with a counterpart in the

akṣāvāpa. Since the

govyacchá is originally a herdsman, Nelson suggests that the

akṣāvāpa may represent an agriculturalist or farmer as a counterpart (

Nelson 2020, p. 260). These rituals may also testify to the transition from a pastoral to an agricultural society: “we have a case of the transposition of the tasks of the herdsman from the earlier Vedic society to that of a priest in the Middle Vedic period. This reflects both the growth of the sacrificial cult at the expense of the earlier non-priestly officiants, along with the steady encroachment of a class of priests who become the sole performers of the ritual tasks” (p. 264). According to Nelson, the progressive acquisition of the principle of non-violence could justify why the herdsman disappears at a certain point in the

rājasūya that he analyzed. Furthermore, the principle of non-violence (

ahiṃsā) seems to be among the founding elements of the Buddhist interest in medicine, but it may not have a samaṇic origin as has hitherto been assumed. Wiltshire supposes rather that it was established already in the Vedic age, as a consequence of the need for a division of powers between the royal and religious castes. The result is a sort of “pax brahmaṇica”—an alliance between the two powers that promised not to wage war on one another, and which only later would be conceptually recovered by the Buddhists to be developed in a totally different way (see DN 5), taking the principle of non-violence (

a[vi]hiṃsā) to indicate a radical rejection of the violence inherent in the ritual process (see

Wiltshire 1990, p. 239).

However, another possible explanation for the importance of the conception of human and animal bodies in the doctrine of non-violence may involve the possibility that this doctrine has both Vedic and external origins within Indo-Aryan culture. Vedic culture contains elements of both sheep people and cattle people, but it places increasing importance on the figure of the cattle—particularly the ox. If we examine the Vedas, we can observe that even in ancient times, attempts were made to justify the killing of similar animals by arguing that sacrificial killing is not a true death (

Tull 1996, p. 225). This indicates some discomfort with animal killing and may be due to the fact that Vedic culture once “mixed” the human body with the animal body, causing one to encroach on the other. However, it was not just any animal body that was used, but that of the ox, which is actually a type of animal considered inedible in the context of initiation ceremonies (

dīkṣā). This does not mean that animal sacrifices are prohibited

in toto. The figure of the ox is controversial; being supremely sacred, it is good for sacrifice but not good for eating. In time this prohibition was extended, and the Brāhmaṇas gradually adopted a non-violent culture, in which the consumption of meat—but also sacrificial violence—is avoided (p. 228). At this point, the figure of the human should not be underestimated. Human sacrifice was a reality, and it is likely that it was practiced in very ancient times, as the Vedas clearly record. However, even in the Vedas, this act underwent a process of reinterpretation. While it is not known exactly when human sacrifice was abandoned, it is known that it was replaced with animal sacrifice through a principle of substitution. Tull believes that in an effort to eliminate human sacrifice, the ancient Indians substituted an animal, humanizing it in order to preserve the principle that the human being was the most important sacrifice. The animal chosen for this humanization was the bull, as it was most closely tied to Vedic culture. The humanization of the bull allowed it to be substituted for the human in the sacrificial act, but it also led to a double paradox: the confusion of the bodies of man and bull, and the confusion caused by the killing of a sacred (even if humanized) animal. This transformation is evident in the following passages: “the immolation of bovine victims represents the immolation of all animals” (p. 229), and “most telling of their great value in the Vedic world, cattle were used to purchase the Soma for the Soma sacrifices” (p. 230). The Buddha shows several elements that refer to the figure of the bull, and he is called by the appellation “bull among men” (

narāsabhaṃ), while the symbol of the bull appears in numerous passages of the canon (

Divino 2023, pp. 5–11). We come, then, to the conception of the body and corporeality.

“The degree to which the Indo-European saw his world as depending upon cattle is evident from a creation myth that describes the origin of the world from a dual sacrifice, of a first man, from which the heavens and earth and the three social classes arise, and of a first ox, from which all animals and vegetables arise.”

In the context of ancient Vedic ritual, the human being is both sacrificer and sacrificed: the human sacrifice is the counterpart of another human, the sacrificer (p. 231). When the substitution process takes place, the human being accepts the “human nature” of the cattle in order to be able to sacrifice it in place of another human. However, the problem is solved at the theoretical level, and only partially at the practical level. The consequence of this choice leads to a crisis of presence that arises to counteract another. In this case, however, the crisis is more manageable, and it is circumscribed in a stricter order of mythological explanations: the cattle, in revenge for the sacrifice of their human siblings, will in turn sacrifice humans in another world (as explained in the myth of Bhr̥gu’s journey to the other world). In the past, cattle “walked erect on two feet”, and also “they had their own sacrificial session” (p. 232). These explanations are just ways to justify the sacrificial choice, managing a risk for human presence to fall into crisis: “the attribution of human qualities to cattle that establishes the basis for using them as ritual substitutes also leads inevitably to a certain discomfort on the part of the sacrificer, since the victim dispatched in the sacrifice has to become to some degree human” (pp. 232–33). Men and bovines used to be one and the same; according to an Indo-Iranian myth, they are twin brothers separated, which also explains “the Vedic practice of wrapping the body of the deceased sacrificer in a cow or an ox hide” (p. 233). This in itself does not prove that the doctrine of non-violence developed internally within Vedic culture, and in fact it may be an external element that influenced Vedism to progressively change its sacrificial modalities: “we may begin to see how non-violence and its attendant doctrine of vegetarianism moved outside the Vedic sacrificial arena, arriving eventually at its predominating position in Indian thought and practice. Of course, similar to the doctrines that form the bedrock of Hinduism (e.g., karma),

ahiṃsā and vegetarianism undoubtedly arose from the coalescence of what perhaps at one time discrete strands of belief and practice (“tribal,” Vedic, Dravidian, etc.)” (p. 238). Attempts have long been made to connect the ascetic heritage of Buddhism and yogic practices with the culture of the Indus Valley. These figures, which for Zysk are probably also the first physicians, are closely associated with the animal kingdom and the figure of the bull, but only recently have the figures of ascetics with taurine horns in the seals of the Indus Valley, considered proto-yogin, been associated with similar representations of Mesopotamian taurine deities who, curiously, also sit with crossed legs (see

Figure 1).

There are several reasons to believe that the theriomorphic figures depicted on various seals of the Indus Valley Civilization had something to do not only with ascetic and protopathic practice (as in the famous case depicted in

Figure 2), but also with medicine. As Zysk states: “[t]he elaborate headdress, the costume with bangles and the implication of trance states achieved through the intense concentration or meditation of yoga suggest that this figure depicts a type of medicine-man, shamanistic in character” (

Zysk 1993, p. 3).

Buddhism, which Bronkhorst considers to be completely unrelated to Brahmanism (

Bronkhorst 2012, p. 9;

Bronkhorst 2017, p. 362), strongly criticizes the institution of Vedic sacrifice, with particular reference to the act of killing animals, which it rejects in its entirety. However, Buddhism makes use of sacrificial symbologies, which Bronkhorst explains as a metaphorical use related to dedication (p. 14). I do not totally agree with this explanation. As expounded in a previous paper (

Divino 2023), Buddhism possesses potential connections with Brahmanism in antiquity, and the choice to use the sacrificial metaphor is attributable primarily to a desire to parody and invert it from the Vedic power order that it represented. Similarly, Buddhism parodies the figure of the ruler, elevating the Buddha to a

cakkavattin, and his teaching to the roar of a lion—a totemic animal of royal power (pp. 18–21). The choice to fraternize with animals is also part of the desire to signal that the ascetic actually inhabits the animal space (see the importance of animals in Buddhist representations, such as in

Figure 3), which is the space of the forest. Ascetic and animal are part of an area that is not a delimited territory, but is what remains outside the delimitation. Equally interesting is Agamben’s definition (

Agamben 2004, p. 55) of the animal environment as

offen (open) but not

offenbar (unconcealed; lit., openable), which seems to recall the ancient Indian meaning of

loka as “open space” (

Wiltshire 1990, pp. 228–29).

3. The Early Buddhist Medical System and Āyurveda

This section focuses on the points of conjunction between Buddhism and Āyurveda—in particular, on the conception of medicine as the science of liberation and the aspiration to eternity.

First of all, the word

āyurveda indicates a form of knowledge (

-veda) related to

āyus- (>

āyur-). This latter word is particularly important, since it is derived from the Indo-European root *

h2ei̯

u- (“vital force, life, long life, eternity”), whence also the Greek

aeí (“always”) comes. This word is related to the old Greek

aiwṓn, which later became the name of the god

aiwṓn, suggesting both “lifetime” and “eternity” (cfr., Latin

aevum). From *

h2ei̯

u- comes the proto-Indo-Iranian root *

hāýu (cfr. Avestan

āiiū), which is the source for the Vedic

āyus. This fact led philologists to interpret

āyurveda as the “science of long life”. However, I would not underestimate the concept of eternity as ‘indefinite time’, preceding the very definition of time.

1 Given the importance of eternal timelessness in Buddhism as a synonym for transcendence from the world,

2 I would also consider medicine as an eternal art, invoking this principle as the only force that can cure from the anomie of disease. This would allow us to surmise that a similar conception was adopted by ancient yogin, who later elaborated on the

materia medica found in the Āyurveda.

3The first mention of this term is in the

Mahābhārata epic (

Wujastyk 2012, p. 31). Here,

āyurveda is described as a science of eight components; thus, this term (

aṣṭāṅga, “eightfold”) is usually adopted to describe medicine as a whole. Wujastyk noted that the idea of an “eightfold” structure is referable to Buddhist philosophy, where the eightfold structure appears quite frequently, from the eightfold path of liberation (

aṭṭhaṅgika magga) to medicine itself. In SN 36.21, eight factors are addressed as the possible causes of disease. This discourse of the Buddha is presented in the context of a question from his disciple Sīvaka, to explain to him that

kamma is not the main source of disease. Rather, there are eight possible causes of disease:

“Bile, phlegm, wind.

Their interaction, and the weather,

Self-careless, overexertion,

And the result of deeds is the eight.”

4(SN 36.21)

As Wujastyk wisely points out, the word indicating the interaction between factors (

sannipāta) is “a technical term from āyurveda that is specific as a modern establishment doctor” (2012, p. 32). However, the use of technical terms in Buddhism is not uncommon. If we examine the description of the

pañcakkhandas, we can see that a significant number of technical terms are used, some of which are quite sophisticated, e.g.,

saññā,

saṅkhāra, or

viññāṇa, whose explanation implicates the use of specific terms such as contact (

phassa), sense-spheres (

saḷāyatana), and so on.

5 Concerning the term

sannipāta, Wujastyk (p. 32) writes:

“This term signals clearly that the Buddha’s list of disease-causes emanates from a milieu in which a body of systematic technical medical knowledge existed. And it is these very factors that later became the cornerstone of classical Indian medical theory, or āyurveda. The historical connection between the ascetic traditions –such as Buddhism and āyurveda– is an important one.”

It is possible to trace several passages in ancient texts expounding Buddhist conceptions of illness. We can also observe some passages of the Buddhist canon in which medical advice and prescriptions seem to be present—for example, in Snp 4.16: “suffering by illness and hunger, they should endure cold and extreme heat” (

ātaṅkaphassena khudāya phuṭṭho, sītaṃ athuṇhaṃ adhivāsayeyya).

“It is possible that some yogins were seen as physicians, who attempted to heal people’s diseases by combining Yoga techniques with a basic understanding of humoral theory and disease. If these yogins remained outside the profession of Ayurveda, they may have rivalled Ayurvedic physicians (Vaidya) in treating people.”

Traditionally, the first appearance of the āyurvedic medical system is attributed to the encyclopedias of Caraka, Suśruta and Bhela. However, Buddhist testimonies could prove a much older origin of this medical knowledge that was only later systematized in the Āyurveda. The first of these treaties, the

Carakasaṃhitā, seems to provide proof of this antiquity. It is the earliest surviving compendium of classical Indian medicine, and it presents an entire chapter on the “Embodied Person” (

Śarīrasthāna), which seems to reveal a yogic method of liberation.

“It is even more surprising to find that this yogic tract contains several references to Buddhist meditation and a previously unknown eightfold path leading to the recollection or mindfulness that is the key to liberation. Finally, Caraka’s yoga tract almost certainly predates the famous classical yoga system of Patañjali.”

The

Satipaṭṭhāna is considered to be one of the oldest meditation techniques. It is notoriously described in suttas such as MN 10 and DN 22, but this method also seems to appear in other suttas (for example, SN 47.28, 47.36, and 47.39).

Wujastyk (

2012) affirms that the same model of the

Satipaṭṭhāna is found in verse 146 of Caraka’s treatise on medicine, where he speaks of “abiding in the memory of reality” (

tattva-smr̥ter upasthānat, p. 35). The Buddhist method aims to establish (

paṭṭhāna) mental presence (

sati) through the contemplation of four elements: body (

kāya), cognition (

citta), feeling (

vedanā), and objects (

dhamma). Any of these elements, apparently, presents a copy of itself inside of itself.

6 One should meditate on this double nature (

kāye kāyānupassī viharati… the same repeats for the other elements). The expression “mental presence” or “mindfulness” (

sati) has to do with both memory and awareness, and Wujastyk (

ibidem) believes that the same terms are intended by Caraka. This seems to be corroborated by the presence of other Buddhist terms in the treatise, the most notable of which is

duḥkha, identified by Caraka as “the final goal of recollection”. This, among other similarities, proves that “Caraka integrated into his medical treatise an archaic yoga method that owed its origins to Buddhist traditions of cultivating

smr̥ti” (p. 36). More than anything else, this evidence demonstrates the importance of the Buddhist method in medical practice. According to Zysk, “medicine was already well-integrated into early Buddhist thought” (

Zysk 2021, p. 4).

As we have seen, the theory of

tridoṣas seems to be a pillar of early Buddhist medicine. This tripartite configuration, which also appears in classical Indian medicine, might be quite old. However, some have argued that it could possibly be derived from an earlier dualistic model comprising only bile and phlegm. According to this theory, these two elements (

dhātu) were developed from an old Vedic dichotomic cosmological partition between fire (

agni) and water (

soma), thus calling back hypothetically to an Indo-European origin (

ibidem). Such a supposition can also explain the enormous similarities between Indian and Greek medicine by way of a common origin (see

Table 3).

If this theory is correct, it would invalidate the other hypothesis that suggests the Indus Valley Civilization as the ancient repository of this medical theory. However, it is also possible to consider the hypotheses of other scholars who propose alternative origins for these medical systems. For instance, the idea of a Mesopotamian origin could potentially explain the similarities between Greek and Indian medicine, as well as the presence of these traditions in the Indus Valley Civilization (

McEvilley 1981,

1993). It should also be noted that the histories of these traditions have undergone significant changes and influences over the course of the millennia, including exchanges and encounters with one another. In particular, Indian medicine had at least one documented exchange with Greek medicine after Alexander the Great, but there were already numerous points of overlap even before this documented exchange.

Now, the system that opposes fire and water could also be found in the

Suśrutasaṃhitā, outlined as an opposition between “hot” and “cold”. The involvement of climate and temperatures in the cause of diseases is also mentioned in SN 36.21, using a very “similar turn of phrase” to the Hippocratic work (p. 14). In Greek medicine, the same division of hot and cold exists, and “it goes back to Aristotle” (p. 20) as well as to Hippocrates himself, who writes that etiology “has an essential environmental component” (

Cosmacini 1997, p. 67). In fact, while also considering geography and climatology, Hippocratic medicine states that “the natural laws (

phýsis) are flanked by culture and human institutions (

nómoi), which in turn have a profound influence on character” (

Parodi 2002, p. 48).

Nevertheless, the

Suśrutasaṃhitā enumerates four pathogenic agents in total, because blood (

śoṇita) is added to the classical three. Blood (called

haîma) also appears in the Greco-Roman medicine, which counts four humors (

khymós)

7 as well: (1)

xanthē kholḗ, (2)

mélaina kholḗ, (3)

phlégma, and (4)

haîma. According to this medical tradition, the prevalence of one of these humors in an individual’s system corresponds to the development of a specific character type (

quattuor humores, see

Table 4), similarly to how āyurvedic medicine outlines different somatic appearances based on humoral prevalence.

It must also be said that blood makes its appearance already in Hippocratic medicine, though in a rather controversial way (

Zysk 2021, p. 10). Furthermore, in Buddhist medicine, we can observe the presence of air as a third humor, which modifies the dualistic Vedic theory of fire/water. The wind (

vāta) would seem to be a humor connected to the importance of the breath in archaic ascetic practices. Air (

prāṇa) is in fact considered to be a fundamental life element in traditional Indian medicine, and it can also be connected to the theory of the five breaths, which I discuss later. In addition, the importance of number three could also be explained as a consequence of the strong influence that Sāṃkhya had both on Buddhism and traditional Indian medicine: “the number three is deliberate in Caraka’s compilation, coming from the number of qualities or properties (

guṇa) expressed in the early philosophical school of Sāṃkhya” (p. 7). This theory is deeply integrated in āyurvedic medicine, especially to describe food qualities and body types concerning diet prescription (see

Table 5).

The Sāṃkhya system divides the world in minimal constitutive entities called

tattvas. However, in verse 151 of Caraka’s treatise, Sāṃkhya is mentioned to divide the world not into

tattvas, but into

dharmas.

8 This clearly suggests, according to

Wujastyk (

2012, p. 36), that for the Buddhists the word

dharma also means “entity” or “fundamental phenomenon”, but this could also imply that in ancient times the Sāṃkhya used the term

dharma and not

tattva, corroborating the hypothesis of a connection with Buddhism in an earlier phase.

9 4. Healing, Transcending: Ascetics’ Cosmological Conceptions of Illness

Buddhism possesses a medical attitude toward the world, due to the mindset of the ascetic as a healer. Therefore, while it is true that

dukkha is irreducible as a concept to simple organic disease, it is also true that such generalized discomfort is undoubtedly understood in medical terms, since its resolution is a healing, and the right means is compared to a medicine. For example, the attainment of

nibbāna is possible only after the purification of

citta (

Johansson 1969, p. 30). The medical metaphor is frequently used: “nibbāna is the state of

citta created when the obsessions and other imperfections have ultimately disappeared and have been replaced by understanding, peace and ‘health’” (p. 33). I suspect that

upakkilesā also carries a strong medical conception in its intended use. A perfect description of the ascetic view on disease can be found in a passage of Dhp 204, which reads “health is the highest end… nibbāna is the highest joy” (

ārogyaparamā lābhā…

nibbānaṃ paramaṃ sukhaṃ).

In his unpublished notes, De Martino marks a series of elements and “psychosomatic relationships” that refer to his research on symbolic efficacy inherent to the problem of the crisis of presence. In this list, there is a short point—a mere suggestion awaiting further development: “the powers of the yogi on the body” (

De Martino 1995, p. 154). In the light of these notes written by De Martino, which are further developed in an important passage from

The End of the World, the statements made in Eliade’s review of

The World of Magic appear clearer. Mircea Eliade praised De Martino’s desire to recognize the real existence of paranormal phenomena and the conception that the world is never “

given” but it is continuously “

made” by human beings throughout history. Some salient passages of Eliade’s review are as follows:

“On the other hand, paranormal powers are not encountered exclusively with primitives and aberrant subjects of the Western world, but also with yogis, fakirs, saints of all kinds, belonging to every sort of civilizations. The needs of the historicist argument forced De Martino to limit his comparisons to the paranormal powers of primitives and those of modern mediums. But the authenticity of yogis’ powers, for example, poses another problem: that of the lucid and rational conquest of these paranormal abilities. It is therefore not necessary to consider only a “historical magical world” (the primitives) and a spontaneous but historically inauthentic regression in this world (the mediums): it is necessary to consider another world accessible, in principle, to everyone and at any historical moment (since the yogic “powers”, for example, are not the exclusive privilege of the Hindūs, nor of a particular historical epoch, since they are attested from the most ancient times to the present day). In a study published in 1937, starting from this same encounter between ethnological documents and paranormal facts, we tried to solve the problem of the reality of paranormal powers in a completely different perspective.”

“His book stands out in its abundant and often inert ethnological production, not only for the new points of view but also for the philosophical interest it presents. Too often one gets the impression that Western philosophy maintains itself in a sort of “provincialism” that excludes it from accessing the great currents of human thought (the primitives, the East, the Far East). Books like this by De Martino help us rediscover the true perspective of an integral humanism in which the experience of a “primitive”, being a yogin or a dáoist, acquire the right of citizenship alongside the best traditions of the West.”

(p. 277)

De Martino employed the term “Magic” in an anthropological sense in order to differentiate between supposed “frauds” and what he viewed as true paranormal capabilities, which he referred to as “psychism.” He argued that these capabilities have yet to be accepted by the academic community due to their misunderstanding as superstition. Thus, De Martino’s research also focused on magical practices—not out of a belief in the supernatural, but out of an understanding of the “culturally conditioned nature” of the human mind. He believed that the human mind can alter the body and the environment not as a result of a supernatural power, but due to its pre-existing abilities. In light of this, De Martino’s interest in yogic practices and the study of meditation becomes more meaningful. While these topics did not feature in his primary publications, it is understandable why De Martino wanted to study them further, given his overall system of thought.

Therefore, when we try to understand the Buddhist conception of disease, we cannot ignore the ascetic sphere of transcendence—a transcendence which, however, does not aim to push the ascetic from a world of suffering to “another” world (perhaps heavenly and without disease). The world itself is the disease, so where does the ascetic “go”? In passages such as Snp 4.4 or 4.8, in which the Buddha critically describes the concept of purity in its dichotomous relationship with the impure, it is clear that the world to be sought is beyond dichotomies. Certainly, the disease exists and suffering is real, but it is all the more real the more we continue to believe in the dualism that it substantiates. In Snp 4.9, the supreme purity is described as beyond visions, inexpressible by opinions and, therefore, also beyond the dichotomous pure/impure relationship. For this reason, the ascetic, in Snp 4.13, is described as not longing for either the pure or the impure—just as those who speak of purity and impurity (Snp 5.8) do nothing but propagate an opinion, not reality.

At this point, the figure of the Buddhist ascetic deserves mention as the bearer of a series of psychic powers (iddhi), which make them above the laws of physics. Although these aspects would seem comparable with De Martino’s idea of magic—and they certainly are to a large extent—they are of no interest to our dissertation on the medical conception, since among these powers, in my opinion, the only ability to transcend the presence is obtained by the ascetic through samādhi, which does not entirely involve the medical conception inherent in the discourse on the protection of presence through “healing” dispositives. However, if we examine the conception of the ascetic’s body, we are faced with the difficulty of expressing what lies one step ahead of transcendence, without elevating oneself completely.

5. Body, Visualized: Evolution of the Somatic Image

The last aspect that I intend to address in this general examination of the theory of disease in Buddhist ascetic thought is the idea of the body. Indeed, the body is the center of these reflections, both in the ascetic exercise and, obviously, as the epicenter of human illness and suffering.

What interests me to investigate in this circumstance is not so much the sick person’s body, but rather the body of the ascetic as a healer. The state of the ascetic is in fact described in various cases as perfectly healed, totally free from disease (

aroga). This condition is peculiar, as it coincides with a transcendence from humanity itself (Snp 4.4). The body is composed only of potential diseases,

10 so what body will the ascetic have that is wholly free from disease?

Even according to the most ancient Indian metaphor concerning corporeality, creation takes place through the dismemberment of the body of the primordial man (

mahāpuruṣa) in a sacrificial form. The world is the result of a series of divisions (

vidadhuḥ) of the body (

Wujastyk 2009, p. 193). The body provides the metaphor for the entire universe: “life in the human world was a mirror or reflection of life in a greater, divine dimension” (p. 195). Therefore, as the human body is the representation of the entire universe—the world conceived in the Vedic tradition as a gigantic body; thus, the sacrifice serves this worldview properly.

Buddhism, on the other hand, shows obsessive attention to the body, presenting various anatomical suttas in which the manifold parts of the body are analyzed and dissected by the Buddha’s surgical gaze. Many examples could be given, such as Snp 1.11, where the body is meticulously analyzed: “walking, standing, sitting, lying, extending and contracting the limbs, these are the movements of the body” (

caraṃ vā yadi vā tiṭṭhaṃ, nisinno uda vā sayaṃ; samiñjeti pasāreti, esā kāyassa iñjanā). The body is described as “held together” by bones and sinews (

aṭṭhinahārusaṃyutto), covered with “flesh and skin” (

tacamaṃsāvalepano). However, “the body is not seen as it really is” (

chaviyā kāyo paṭicchanno, yathābhūtaṃ na dissati). It also comprises “guts, belly, liver, bladder, heart, lungs, kidney, and spleen” (

antapūro udarapūro, yakanapeḷassa vatthino; hadayassa papphāsassa, vakkassa pihakassa ca…)—all things that are hidden from our sight. The list goes on and on, including blood, synovial fluid, bile, and grease (

lohitassa lasikāya, pittassa ca vasāya ca). Although here the dissection of the body serves to indicate its transience—its decomposition, which is a symptom of the ephemerality of all things (

yadā ca so mato seti…)—it is evident that the Buddha here displays a very detailed anatomical knowledge.

“Then in nine streams the filth always flows. Muck from the eyes, wax from the ears, and snot from the nostrils. The mouth sometimes vomits bile, sometimes phlegm. And from the body, sweat and wase come out. Then, there is the hollow head, filled with brain, and governed by ignorance. Only the fool thinks it’s lovely.”

11

This constant and complete dissection of the body is an exercise that the Buddha often repeats; it is disorienting, and it has a strong impact for those who hear it, but meditation is the same: deconstruction of one’s identity, as the body is dissected by these discourses. Other suttas containing anatomical views or analysis of the body composition can be found in AN 3.36 4.157, 5.78, 9.34, 10.60, and 10.108.

In Snp 2.2, the body is mentioned again, this time bringing attention to the putrefaction process. However, now the putrefaction does not serve as a reminder of the transience of life, but to signal a disgusting, impure, undesirable element. If putrefaction is such a sign of terrible things, then why did the ancients sacrifice the dead? In this case, the Buddha uses the putrefied body to send another message—one of rejection of the Brahmanic authority and rituals. Another clear example of this anti-Brahmanic position is evident in Snp 2.7, where the proliferation of diseases is attributed precisely to the killing of animals:

“Once, there used to be three kind of illnesses:

Greed, starvation, ageing.

Now, due to the slaughter of cows

illnesses grew to be ninety-eight.

This unworthy violence,

has been perpetuated as an ancient custom.

Sacrificers who seek for righteousness.”

12

The ascetic is often regarded as a healer, and this understanding is rooted in the representations of their body. In the Indian tradition, the ascetic is symbolized by the figure of Śiva, and their presence can also be found in the artifacts of the Indus Valley Civilization, which portray them as transcending human corporeality. According to Vedic myth, human corporeality is a limit beyond which lies the creation of the world, and the ascetic’s body symbolizes a realm that surpasses this boundary. They are often depicted in a theriomorphic form, surrounded by animals that represent the other-than-human dimension. This points to the ascetic’s ability to access the unknown and savage world outside of the city, which is believed to contain the secrets of healing.

In the account of the Buddha’s ascetic experience, when he was still trying out ascetic techniques that he would later criticize as mortifying and too extreme, we can find a passage (MN 12) in which the Buddha’s fasting had brought him to a state of extreme thinness, to the point that, by touching his belly, he was able to grasp his own backbone, now visible by the total absence of flesh, of body (see the famous representation in

Figure 4). Here, then, is where reflection on the body once again becomes unavoidable. The ascetic’s body is a battered, starved, damaged, sick body. How can the ascetic, who must cure human suffering as a physician, accept such terrible mortifying practices? This asceticism leads to more suffering, not liberation, and it is therefore harshly criticized by the Buddha, who proposes a different, contemplative asceticism of his own. The symbolism of the spine (

vertebral column), moreover, is very important as it relates to both yogic practice and medicine in general (

McEvilley 1993).

In many traditional medicines, the cause of disease is thought to be from an external source, such as divine punishment or demonic possession. As a result, the remedies used to treat the condition are often composed of herbs, plants, and animal parts procured from the environment outside of the village. As the ascetic becomes more familiar with this unknown world, their body is changed and altered, slowly becoming something more than human. Through this transformation, the ascetic begins to understand the alienating nature of the illness and how it can disrupt the social balance. By gaining knowledge of the external world, the ascetic is then able to create solutions that can help to restore this equilibrium.

“It is as if determining the border between human and animal were not just one question among many discussed by philosophers and theologians, scientists and politicians, but rather a fundamental metaphysico-political operation in which alone something like “man” can be decided upon and produced. If animal life and human life could be superimposed perfectly, then neither man nor animal—and, perhaps, not even the divine—would any longer be thinkable.”

The division or subdivision of the body in the old Vedic literature was not meant for medical purposes, but rather for ritual and sacrificial intents: “it is driven by structural imperatives such as the existence of thirty-six celestial worlds. […] The point is to draw a magical, or at least symbolic, homology between the victim, the officiants, the divinities, and even the world at large” (

Wujastyk 2009, p. 194). Indeed, it is commonly accepted that Vedic anatomic knowledge was quite poor (

Zysk 1991, p. 16).

However, the Vedic world provides for a complex concept of breath (

prāṇa) that, as we have seen previously, is also very important for Buddhists. As far as the Vedic literature is concerned, the breath is often associated with

apāna, which is supposed to be an exhalation. In any case, in the Vedas, the breath is already connected to a vitalistic conception in which “

prāṇa and

apāna should consistently be translated as thoracic and abdominal breaths respectively” (

Brown 1919, p. 112). The life breath

prāṇa, as a life force that can be managed and improved by exercise and has five possible variants, begins to appear in Buddhism and the Upaniṣads.

“Their concept of the five breaths carried over into early Ayurveda, where its enumeration and explanations were adopted into to a medical context. Although wind in early Ayurveda is varied and incorporates a diversification of ideas, the use of a fivefold enumeration of the vital breaths indicates an adaption from ancient Indian traditions of asceticism, which included practices of breath-control (prāṇāyāma), as part of their religious discipline.”

The importance of breathing has actually been mentioned since the Upaniṣads, where “many ideas concerning breath and breathing” began to be developed (

Wujastyk 2009, p. 196)—for example, the division of breath into five categories “based on location and bodily function” (

ibidem). Nevertheless, these mentions in the Upaniṣads could possibly be the testimony of a much older tradition. The “five breaths” are also mentioned in the Brāhmaṇas (

Cavallin 2003, p. 24), the

Atharvaveda (10.2.13), and the

Carakasaṃhitā (12.8). Nevertheless, this doctrine of five breaths became important for classical Indian medical thought only from the

Āyurvedasūtra, which is a much later work (

Wujastyk 2022b, p. 400). Yogic texts such as the

Gorakṣaśataka and the

Yogabīja describe the technique of breath retention (

kumbhaka), also called

ujjāyī, as capable of curing bile disorders (

śleṣman) as well as imbalances of the body’s channels (

Birch 2018, p. 15). The importance of breathing is pivotal also in Greek medicine; Hippocrates wrote an entire book on breaths (

perì physō^n) to explain how

pneŷma (understood as

āḗr) is crucial as being “the sole cause of disease” (

Zysk 2021, p. 20).

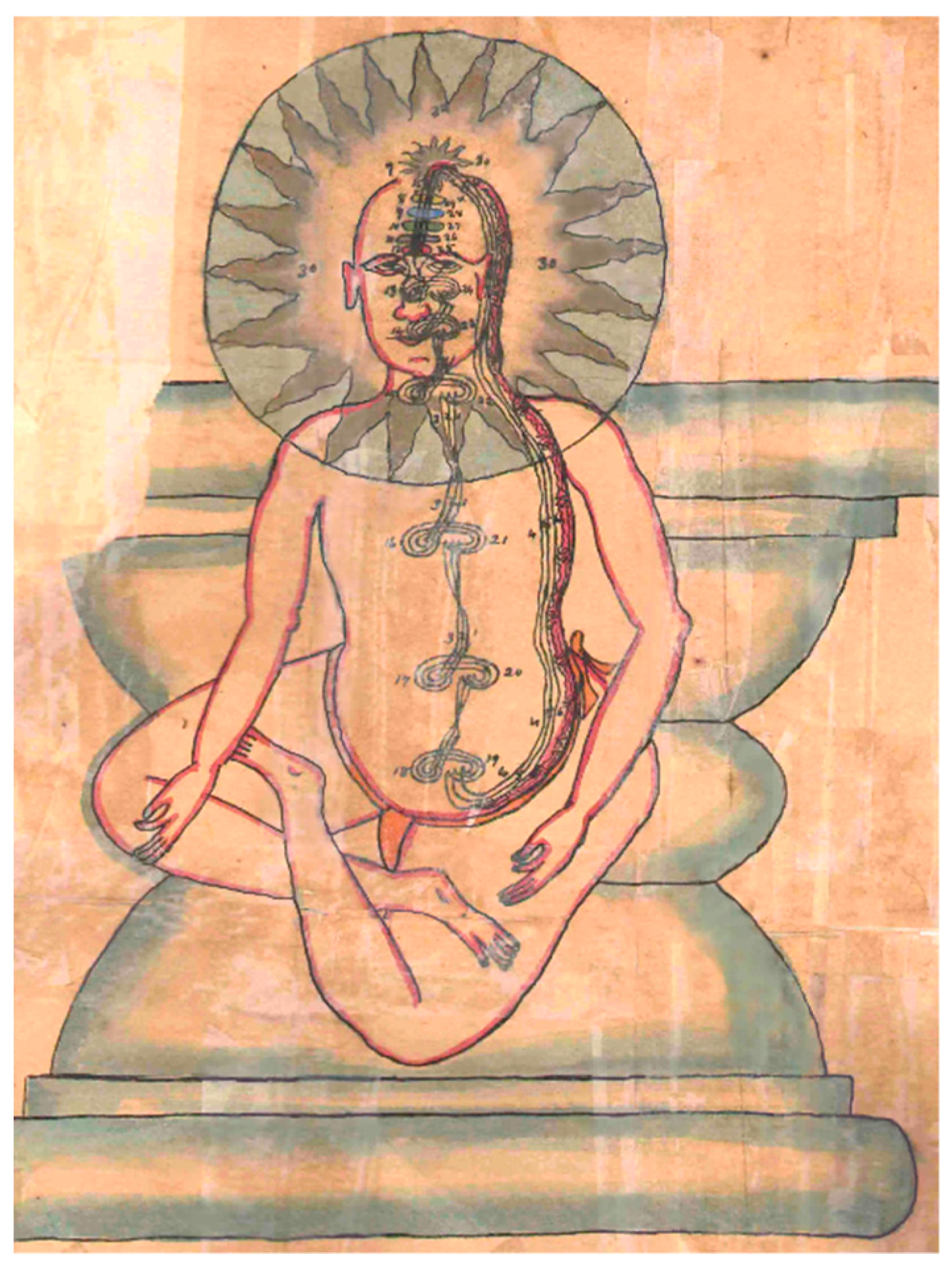

In the ascetic traditions of India, the body is represented through metaphors of absence and presence (

Figure 5). For example, in the Jain tradition, the saint one, who has reached perfection, cannot be described in any linguistic terms: “any adjective is inappropriate and inadequate” (

Wujastyk 2009, p. 197). Nonetheless, we can speak of them. This is possible due to the apophatic tool: “by describing what he is not” (

idibem). This particular condition is represented in visual art, where the body of the ascetic is represented with the same principles of illusory contours, like a Kanizsa triangle.

The unique condition of amodal perception refers to the presence of an absence. The body of the ascetic is absent as a presence of an absence, i.e., it is present even in its absence (see

Figure 6). This philosophy appears to depict the liberated body as the absence of something else, but this form of expression is also present in Buddhism. Wiltshire provides a valuable reconstruction of some aspects of ancient Buddhism, which he appears to trace back to the same conception of absence—in particular, the central theme of

nibbāna as developed from the concept of the absence of the world (

loka), which he calls “

loka absentia”, and which refers us to a previous study that I conducted on the end of the world (

Divino 2023, p. 15). Regarding the body instead, which is the matter of our interest here, Wiltshire believes that the Buddhist notion of

anattā is nothing more than the conceptualization of the idea of an absence of the body, or “

kāya absentia” (

Wiltshire 1990, p. 263). To understand why the body is so important in this conception of “absence” and “presence”, we must remember that the physical body in the Buddhist thought “is not objectified as physical substance, for example, in contrast to mind, but rather as a combination of processes or events” (

Wujastyk 2009, p. 198). Thus, the word

kāya does not refer to a strictly material body, nor to mind and thought, although it comprises both in a different and wider conception of the subject. Although life as such cannot be reduced to this idea of “body” either,

kāya seems to encompass both subjective experience and all of the fields of perception and cognition. Therefore, the liberated subject that

exists—even after the transcendence from these bodily limitations—cannot be represented, except by using the metaphor of a “presence through an absence”.

This oscillation between absence and presence, and the very idea of “not-self” as the absence of the body whose presence is a “being-there without the need for a body”, cannot fail to make us look at the work of the anthropologist Ernesto De Martino, whose reflection on the presence outlines an anthropological theory on the body and on health that has a lot to do with Buddhist conceptions.

In Buddhist visual culture, the representation of the Buddha’s body is affected by this particular idea of presence and absence. The ancient Buddhist art makes use of a so-called aniconic representation (

Karlsson 2006;

and Huntington 1990) to represent the condition of the Buddha’s body as present despite being invisible in the anthropomorphism of common bodies, just as the ascetic was endowed with a body that bordered human limits.

There are two possible representations of the Buddha’s body: On the one hand, in the phase of Indian aniconic art, the Buddha is not yet physically represented, as is the case following the more massive Greek influence. The Buddha cannot be represented, as his body transcends human limits; therefore, the artists choose to represent the Buddha’s body with metaphorical art, using symbolic elements that recall its importance, such as the

dhamma wheel or, in this case, the

pīpal tree (

ficus religiosa) under which the Buddha attained enlightenment (

Figure 7). On the other hand (

Figure 8), there is a much more recent representation (18th century) belonging to the Tibetan

rDzogs Chen; this tradition also refers to metaphors—such as light, central to representing enlightenment since ancient times (

Divino 2023, p. 23, note 10)—but the Buddha’s body is present anthropomorphically, although it is transcendent in light itself, in the form of a “rainbow body” (

’ja’ lus). In both cases, we witness an attempt to depict the absence of a body that becomes present in its “not-being-a-common-body”.

6. Conclusions: The Crisis and the Ascetic Healer

The driving element of this study is Ernesto De Martino’s anthropological theory in reconstructing the ascetic ideal at the base of ancient Buddhism. We have seen that Buddhist asceticism is heavily intertwined with the medical tradition, and we can suppose that the basis of this peculiar connection is the role of the ascetic as a master of “presence”. After demonstrating how Buddhism preserves an archaic memory of medical knowledge that was also the basis of traditional Indian medicine, we have reflected on the possibility of finding Demartinian concepts such as “presence” and “crisis” at the root of the medical interest of these ascetics. Demartinian theory is complex and presents some weaknesses and issues. However, following appropriate comparisons, we can correct some controversial elements and see how this anthropology can also be adapted to the Buddhist world. According to De Martino, the crisis of anguish in the face of existential threats arises at the beginning of human experience. It is in the definition of “presence”—of a “being there” in the emerging cultural history and social structure—that the ancient ascetic, whether a magician or a shaman, experiences the crisis of presence for themselves, venturing to the boundaries of the established values, inhabiting both society and the anguishing chaos of origins. In these non-places, they find the techniques of presence.

Buddhism asserts that human beings are in constant crisis—that is, in a constant state of suffering (

dukkha), as their expectations of the world are unfulfilled, proving to be illusory, but they do not want to admit this fundamental transience of the things to which they are attached. For De Martino, “is to be considered

ill”, Lesce writes, “the subject who is incapable of producing and at the same time recognizing the signs of his operation in that which, for him, exists externally” (

Lesce 2019, p. 178). The only note that needs to be added is that for Buddhism this condition is intrinsic to the world. In other words, the self is born already lost; the world is born already sick. It does not fall ill after its birth, but is born as the disease itself. For De Martino, madness (

follia) that arises from the feeling of loss of the self (

perdita del sé) has three main reasons: (1) the perceived threat of the nothingness that is believed to be imminent; (2) “the danger that, with the disappearance of the categories, man is no longer able to forge a form” (p. 179), and here the form also returns in Buddhism (

rūpa) as the beginning of the chain of productions knowledge that shape the world; and (3) “the impossibility for the restless presence to go beyond its critical contents in the ideality of the community form”. This last aspect is made possible by the ascetic. For Buddhists, we recall, the goal of the ascetic is the very transcendence of the world, in a worldliness that is neither world nor other-world. The “magic person”, for De Martino, is someone who precedes these cognitive deceptions, for which “the self and the world are not definitively given as distinct and guaranteed values” (

ibid.); is he perhaps describing a similar figure at the

samaṇa?

The idea of the “end of the world” is central to the anthropological theory of presence, and I have also shown how Buddhism has its own unique conception of the end of the world (lokanta). However, a thorough analysis of this concept alone requires a separate study that falls outside the scope of medical anthropology, which is the focus of this article. I have therefore undertaken to develop a specific study on the concepts related to the end of the world based on the Pāli Canon.