The Miracle of the Bloody Foreskin at the Council of Charroux in 1082: Legatine Authority, Religious Spectacle, and Charismatic Strategies of Canonical Reform in the Era of Gregory VII

Abstract

:1. Canonical Reform and Legatine Authority in the Era of Gregory VII

2. The Limits of Legatine Authority: The Example of Tours

3. The Legatine Councils and Conciliar Speech

4. Spectacle as Conciliar Speech at the Council of Charroux

5. Charismatic Spectacle and Legatine Authority

De quodam prelato cupido et avaro

I.

Errant qui credunt gentem periisse Ciclopum:

En, Poliphemus adest multiplicator opum,

Excedens alios uultuque minisque Ciclopes,

Tantalus alter, inops esurit inter opes.

Cum sit tam capitis quam mentis lumine cecus,

Dedecus omne docet, dedocet omne decus.

Rupe caua latitans cupiendo, timendo laborat;

Quosque tenere potest, ossa cutemque uorat.

Ecclesiam lacerat, deglutit publica fratrum,

Nec saciare potest mentis hians baratrum

Pontificum legate, decus, pater optime partum,

Ad solitum redeat, coge nefas, aratrum.

II.

Exilaras mestos, Hilaris pater, Hilarienses,

Cuius uirga regit, docet accio Burdegalenses:

Iura foues reprimisque dolos, sed digna repenses

Qui delere uolunt que tu, pater optime, censes.

Luce tua remoue tenebras animosque serena;

Dumque redis nobis redeant solacia plena

Afficiatque semel Polifemum debita pena.

Tam caput elatum confringe minasque refrena.

III.

Edibus in nostris ferus hospitibus Diomedes

Intulit insidias, fecit manus impia cedes;

Nunc moriens hostis nostras sibi uindicat edes

Ut suus in dotes proprias habeat Ganimedes.

Iusticie legate rigor, defensio ueri:

Arbitrio cuius pendet moderatio cleri:

Hoc tantum facinus prohibe dignum prohiberi;

Hostis frange minas et nos assuesce tueri.

I.

Those people are mistaken who believe that the Cyclopes’ clan died off:

look, a Polyphemus is here who makes his wealth manifold.

Outdoing the other Cyclopes in both his demeanor and threats,

he is a second Tantalus, hungering needily amid abundance.

Since he is blind spiritually as well as physically,

he teaches every dishonor and unteaches every honor.

Lurking in a cliffside hollow, he toils in desire and fear;

and those of whom he can lay hold, he devours their bones and flesh.

He tears apart the Church, he gobbles the brothers’ communal property,

but he cannot satisfy the yawning chasm of his mind.

Pontifical legate, glory, best father of fathers,

force this wicked person to return to the usual plow.

II.

You gladden glad father the sad followers of St. Hilary,

you whose rod rules the people of Bordeaux, whose conduct teaches them:

you cherish laws and restrain treachery, but may you make fitting returns

to those who wish to destroy what you recommend, best father.

Through your light remove darkness and brighten hearts;

and as you return, may complete solace return to us,

and may due punishment cause harm to Polyphemus once and for all.

shatter the head that has risen so high and restrain the threats.

III.

In our house a savage Diomedes

laid snares for guests, an impious hand caused bloodshed;

and the enemy now dying claims our house for himself

so that his Ganymede may have it as his dowry.

Legate, rigor of the justice, defense of truth,

upon whose judgment depends the governance of the clergy:

forbid this great crime, which deserves to be forbidden;

break the threats of the enemy and keep the habit of protecting us).

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | |

| 2 | The miracle account is published in de Monsabert (1910, pp. 39–41). |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | As when Amatus convened the council of Poitiers in 1075 for the punishment of Isembert II, Bishop of Poitiers, in spite of the pope’s earlier order commanding Isembert to appear in Rome for discipline at the pope’s Lenten synod. See Brown (2020, pp. 218–19). |

| 6 | The episode is known chiefly from the complaint that the canons of Saint-Martin addressed to Pope Urban II. See Delisle (1840–1904, vol. 12, pp. 459–61); see also Farmer (1991, pp. 44–46). |

| 7 | |

| 8 | My thinking here is indebted to the ideas on representation, hyper-mimesis, and the charisma of art in Jaeger (2012, pp. 98–133). |

| 9 | “Quem enim honorem mihi Ecclesia tantae Dignitatis Romano Pontifici ulterius reservaret, si Legato nostro processionis gloriam exhiberet?” (Delisle 1840–1904, vol. 12, pp. 459–60). (For what honor would the Church of such a dignified Roman Pontiff further reserve for me, if it presented the glory of a procession to our legate?) |

| 10 | The career of Amatus of Oloron offers a well-documented case in point. See Fazy (1908, pp. 77–140); Degert (1908, pp. 33–84); Cursente (2013). Concerning his consecratory activities, see especially Richard-Ralite (2017); Brown (2017, 2018, 2021). |

| 11 | Amatus’s expedition in Catalunya has drawn little attention. Documentation of his activity survives among the records of diverse churches and monasteries in the region. See Catalunya Romànica (1984–1997) including volume 5, El Gironès, la Selva, el Pla de l’Estany, p. 402; volume 6, Alt Urgell, Andorra, pp. 67, 118, 121; volume 24, El Segrià, Les Garrigues, el Pla d’Urgell, la Segarra, l’Urgell, p. 420; volume 25, El Vallespir, el Capcir, el Donasà, la Fenolleda, el Perapertsès, p. 366. See also Diago (1603, pp. 136–37). |

| 12 | Fazy, “Notice sur Amat,” pp. 85–86. Degert, “Amat d’Oloron,” pp. 49–53. |

| 13 | “… Dixit chrisma illud non consecratum, sed execrandum, asinorum magis unctioni convenire quam christianorum” (Delisle 1840–1904, vol. 14, p. 50). |

| 14 | |

| 15 | According to an account from Marmoutier, Ralph had already been excomunicated by Amatus when he appeared before the legates at Dol. See Fazy (1908, p. 98); Delisle (1840–1904, vol. 14, p. 96). |

| 16 | On the influence of Poitiers and southwestern France on developments in eleventh-century canon law, see Blumenthal (2009, pp. 87–100); Rolker (2009, pp. 59–72); Rennie (2013); Goering (2009). |

| 17 | On the councils at Poitiers, see Brown (2020); Rennie (2011); Villard (1986). In addition to the councils at Poitiers in 1075, 1078, 1081, and 1082, evidence suggests a previously unrecognized council in 1079, the date normally assigned to a charter introducing reforms to the community of canons at Saint-Hilaire. The charter was signed by Amatus in his capacity as legate, in addition to the archbishop of Bordeaux, Bishop of Poitiers, trésorier of Saint-Martin de Tours, and the abbots of Saint-Martial de Limoges, Saint-Savin, Saint-Jean d’Angély, and Saint-Junien, among others, an assembly whose size and dignity is indicative of a council assembly convened under the authority of the legate Amatus. See Rédet (1848, pp. 97–99). |

| 18 | “Nec suus episcopus, nec suus monachus” (de Broussillon 1903, vol. 2, p. 220); see also Cursente (2013, p. 183). |

| 19 | “Postquam vero expulsus est a sede Episcopatus sui, ille execrabilis homo, fax furoris, fomentum facinoris, adversarius justitiae, filiae superbiae, virus suae invidiae in nos effudit, per Amatum (suum dico, non nostrum) nos accusavit: quin etiam, ad nostrae summum dedecus Ecclesiae, ipse Deus invidiae, puteus perfidiae, Ecclesiae nostrae adversarium, veritatis inimicum, pecuniae servum, arrogantiae filium, Amatum, Turonum conduxit” (Delisle 1840–1904, vol. 12, p. 459). (But after he had been expelled from the seat of his episcopate, that execrable man, the firebrand of fury, the kindling of crime, the enemy of justice, the daughter of pride, poured out upon us the venom of his envy, and accused us through his Beloved [Amatus] (I mean his, not ours): why even to the supreme disgrace of our Church, the man of Tours, the very God of envy, the pit of perfidy, bribed Amatus [his Beloved], the adversary of our Church, the enemy of the truth, the slave of money, the son of arrogance). The author develops a pun based on the name Amatus, meaning beloved, that may be read, in the context of the author’s other hyperbolic calumnies and slanders, as implying that Amatus and Ralph are lovers. |

| 20 | The author specifies the presence of Amatus of Oloron; Guy, Bishop of Limoges; and Almarus, Bishop of Angoulême, subsequently referring to them as a “council of bishops” (Episcoporum consilio). See de Monsabert (1910, p. 40). |

| 21 | “Adquiescit eius aliorumque piis precibus, statuunt diem quo tante virtutis omnibus venientibus simul et loci quo habebatur indicium daretur ostensio” (de Monsabert 1910, p. 39). |

| 22 | The precise chronology of the reconstruction of the abbey church after the fire of 1048 is a matter of some debate and uncertainty. However, evidence strongly supports dating the crypt, the platform for the high altar, and the sculptures of the rotunda tower (and thus completion of the tower itself after 1082). The well-documented invention of the sainte Vertu in 1082 marks the beginning of work on a monumental crypt to house and expose this new relic. The consecration of the high altar above the completed crypt in 1096 marks the conclusion of this construction. The capitals of the lower elevation of the rotunda tower overlooking the altar are exemplars of the so-called “fat leaf” or “feuille grasse” style that proliferated in Poitou in the late eleventh century. As previous scholars have observed, these sculptures are intimately related to those of the chevet at Saint-Hilaire-le-Grand in Poitiers and in the nave of Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe. See discussion in Camus (1992). The “fat leaf” capitals, found in the first six bays of the nave at Saint-Savin, belong to the last phase of construction of the church, after ca. 1080. Those at Saint-Hilaire likewise can be dated to the final phase of construction associated with the vaulting of the church beginning after ca. 1074. Dedicatory inscriptions on two of the chevet capitals at Saint-Hilaire further point to a date in the late eleventh century, including one inscription recognizing the patronage of UGO MONEDARIUS (Hugh the Moneyer), a prominent layman associated with the mint at Melle and documented in numerous charters from the region between 1060 and 1097. See Favreau et al. (1974, pp. 66–67). The early date for the capitals at Charroux of ca. 1060, proposed by Camus and followed by McNeill (2015, pp. 210–11), must be rejected in favor of a date after ca. 1082. The historical, architectural, and artistic evidence suggest that the crypt, altar platform, and rotunda tower, which are after all architecturally integral to each other, were all completed during the same campaign, during the period ca. 1082–1096. |

| 23 | On the concept of performance culture, see Hibbitts (1992, pp. 873–960, 882–84) and passim. On art and performance culture in the Middle Ages, see Dierkens et al. (2010). |

| 24 | “Adest dies: pervenitur ad locum, comitante pariter gaudio cum tremore; ostenso loco, destruitur …” (de Monsabert 1910, p. 40). |

| 25 | On the distinction between aura and charisma, see Jaeger (2012, pp. 98–133). Jaeger describes aura as a power proper to relics and charisma as quality characteristic of icons, drawing a distinction between the abstraction of the relic and representational presence of the icon. The liturgy as a representational medium may be compared in its iconicity and charismatic potential to that of representational art in Jaeger’s argument. |

| 26 | See discussion in Brown (2021, pp. 220–21). |

| 27 |

References

- Aurell, Jaume. 2022a. The Notion of Charisma: Historicizing the Gift of God on Medieval Europe. Scripta Theologica 54: 607–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurell, Jaume. 2022b. Introduction: The Charisma of the Liturgy in the Middle Ages. Religions 13: 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, Uta-Renate. 2009. Poitevin Manuscripts, the Abbey of Saint-Ruf and Ecclesiastical Reform in the Eleventh Century. In Readers, Texts, and Compilers in the Earlier Middle Ages. Edited by Martin Brett and Kathleen G. Cushing. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Brouillet, Amedée. 1856. Description des Reliquaires Trouvés dans l’Ancienne Abbaye de Charroux. Poitiers: Imprimerie A. Dupré. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Peter Scott. 2017. The Chrismon and the Liturgy of Dedication in Romanesque Sculpture. Gesta 56: 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Peter Scott. 2018. Amat d’Oloron à la Sauve Majeure: l’esprit bâtisseur et son guide dans l’architecture religieuse de l’Aquitaine à la fin du XIe siècle. Les Cahiers de Saint Michel de Cuxa 49: 151–66. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Peter Scott. 2020. Détruire un autel: Amat d’Oloron, Bérenger de Tours, l’abbaye de Montierneuf, et les débuts de la ‘réforme grégorienne’ au concile de Poitiers en 1075. Cahiers de Civilisation Médiévale 252: 211–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Peter Scott. 2021. La cathédrale romane d’Oloron des origines jusqu’à la prise de Saragosse (ca. 1060–1117). In Transpyrenalia: Échanges et Confrontations Entre Chrétiens et Musulmans à L’époque du Vicomte de Béarn Gaston IV et du roi d’Aragon Alphonse Ier (1090–1134). Edited by Pierre-Louis Giannerini. Édition de la Maison du Patrimoine. Oloron-Ste-Marie: Association Trait-d’Union Oloron-Saine-Marie, Saint-Eugène, Oloron-Sainte-Marie, pp. 218–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cabanot, Jean. 1981. Le trésor des reliques de Saint-Sauveur de Charroux, centre et reflect de la vie spirituelle de l’abbaye. Bulletin de la Société des Antiquaires de l’Ouest et des Musées de Poitiers 4: 103–23. [Google Scholar]

- Camus, Marie-Thérèse. 1992. Sculpture Romane du Poitou: Les Grands Chantiers du XIe Siècle. Paris: Editions A&J Picard. [Google Scholar]

- Catalunya Romànica. 1984–1997. 27 vols. Barcelona: Fundació Enciclopèdia Catalana.

- Cowdrey, Herbert Edward John. 1998. Gregory VII. Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 355–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cowdrey, Herbert Edward John. 2008. The Register of Pope Gregory VII, 1073–1085, an English Translation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crozet, René. 1937. Le voyage d’Urbain II en France (1095–1096) et son importance au point de vue archéologique. Annales du Midi 49: 42–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cursente, Benoît. 2013. L’action des légats. Le cas d’Amat d’Oloron (vers 1073–1101). Les Cahiers de Fanjeaux 48: 181–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Broussillon, Arthur Bertrand. 1903. Cartulaire de l’Abbaye de Saint-Aubin d’Angers. 2 vols. Paris: A. Picard et Fils. [Google Scholar]

- de Monsabert, Pierre. 1910. Chartes et Documents pour Servir à l’Histoire de l’Abbaye de Charroux. Poitiers: Société Française d’Imprimerie et de Librairie. [Google Scholar]

- Degert, Antoine. 1908. Amat d’Oloron: Ouvrier de la réforme au XIe siècle. Revue des Questions Historiques 94: 33–84. [Google Scholar]

- Delisle, Léopold, ed. 1840–1904. Recueil des Historiens des Gaules et de la France. 24 vols. Paris: Victor Palmé. [Google Scholar]

- Diago, Francisco. 1603. Historia de los Victoriosissimos Antiguos Condes de Barcelona. Barcelona: Sebastian de Cormellas. [Google Scholar]

- Dierkens, Alain Gil Bartholeyns, and Thomas Golsenne, eds. 2010. La Performance des Images. Brussels: Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, Sharon. 1991. Communities of Saint-Martin: Legend and Ritual in Medieval Tours. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Favreau, Robert. 1989. Le concile de Charroux de 989. Bulletin de la Société des Antiquaires de l’Ouest et des Musées de Poitiers 3: 213–19. [Google Scholar]

- Favreau, Robert, Jean Michaud, and Edmond-René Labande. 1974. Corpus des Inscriptions de la France Médiévale. Ville de Poi-tiers: I. Poitou-Charente, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fazy, Max. 1908. Notice sur Amat, évêque d’Oloron, archevêque de Bordeaux et légat du Saint-Siège. In Cinquième Mélanges d’Histoire de Moyen Âge. Paris: F. Alcan. [Google Scholar]

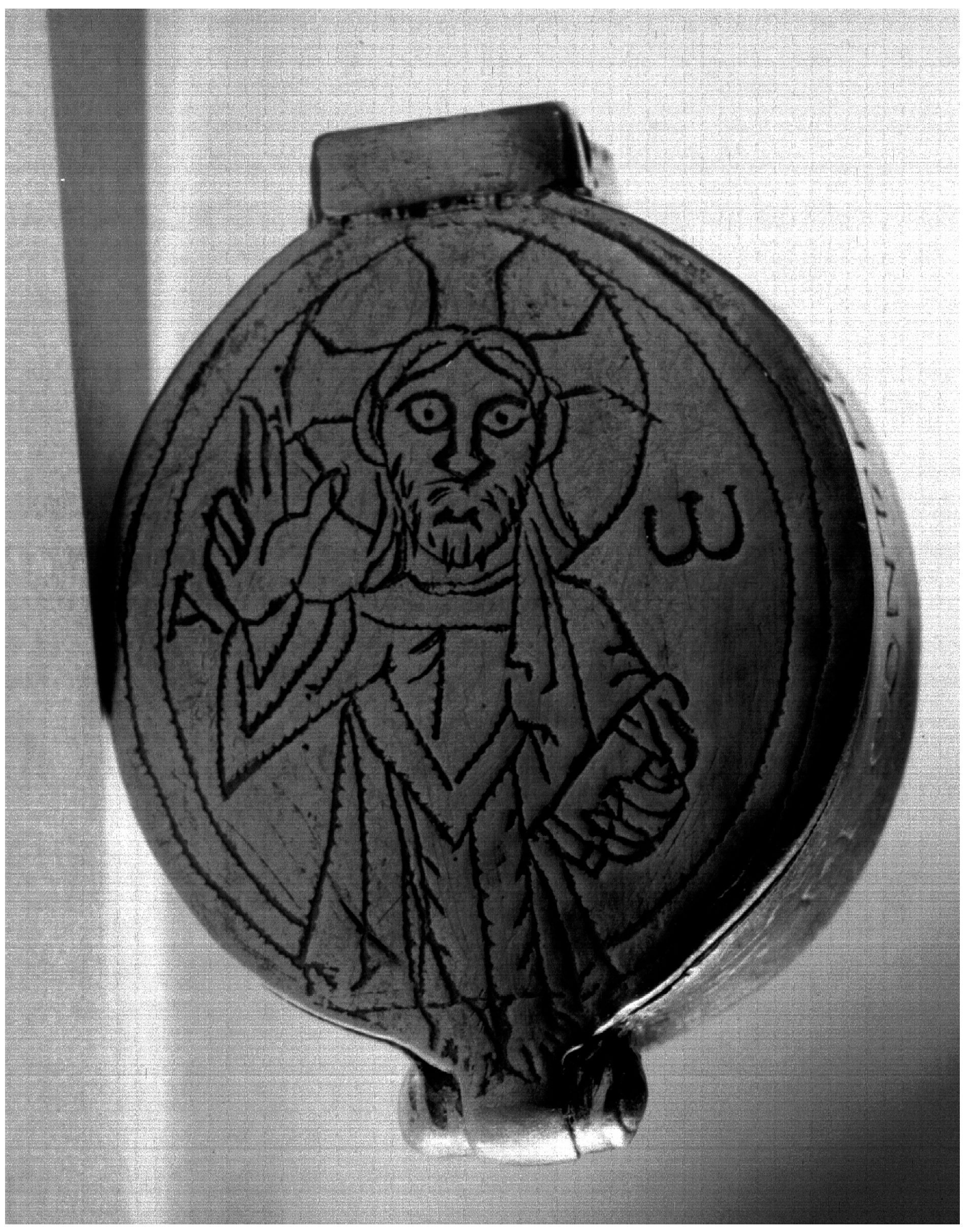

- Frolow, Anatole. 1966. Le médaillon byzantin de Charroux. Cahiers Archéologiques. Fin de l’Antiquité et Moyen Âge 16: 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriele, Matthew. 2011. An Empire of Memory: The Legend of Charlemagne, the Franks, and Jerusalem before the First Crusade. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goering, Joseph. 2009. I. Bishops, Law, and Reform in Aragon, 1076–1126, and the Liber Tarraconensis. Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte: Kanonistische Abteilung 95: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjeltchan, Sasha. 2019. Fixing History: Time, Space, and Monastic Identity at Saint-Aubin in Angers ca. 1100. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Halphen, Louis. 1906. Le Comté d’Anjou au XIe Siècle. Paris: Alphonse Picard et Fils. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbitts, Bernard J. 1992. ‘Coming to Our Senses’: Communication and Legal Expression in Performance Cultures. Emory Law Journal 41: 873. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, C. Stephen. 2012. Enchantment: On Charisma and the Sublime in the Arts of the West. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill, John. 2015. Building Jerusalem in Western France: The Case of St-Sauveur at Charroux. In Romanesque and the Mediterranean: Points of Contact Across the Latin, Greek and Islamic Worlds, C. 1000 to C. 1250. Edited by Rosa Bacile and John McNeill. Leeds: British Archaeological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, Charles Radding et Francis. 2003. Theology, Rhetoric, and Politics in the Eucharistic Controversy, 1078–1079: Alberic of Monte Cassino against Berengar of Tours. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rédet, Louis-François-Xavier, ed. 1848. Documents pour l’Histoire de l’Église de Saint-Hilaire de Poitiers. In Mémoires de la Société des Antiquaires de l’Ouest, 14 (for 1847). Poitiers: Société des Antiquaires de l’Ouest. [Google Scholar]

- Remensnyder, Amy. 1995. Remembering Kings Past: Monastic Foundation Legends in Medieval Southern France. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rennie, Kriston R. 2010. Law and Practice in the Age of Reform: The Legatine Work of Hugh of Die (1073–1106). Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Rennie, Kriston R. 2011. The Council of Poitiers (1078) and Some Legal Considerations. Bulletin of Medieval Canon Law 27: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rennie, Kriston. 2013. The Collectio Burdegalensis: A Study and Register of an Eleventh-Century Canon Law Collection. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Richard-Ralite, Jean-Claude. 2017. Amat d’Oloron et la dédicace de l’autel de l’abbaye de Gellone (Dimanche 13 août 1077). Études Héraultaises 48: 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rolker, Christof. 2009. The Collection in Seventy-four Titles: A Monastic Canon Law Collection from Eleventh-Century France. In Readers, Texts, and Compilers in the Earlier Middle Ages. Edited by Martin Brett and Kathleen G. Cushing. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Somerville, Robert. 1972. The Case Against Berengar of Tours: A New Text. Studi Gregoriani 9: 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Treffort, Cécile. 2007. Charlemagne à Charroux: Légendes de fondation, histoire architecturale et créations épigraphiques. Revue Historique du Centre-Ouest 6: 265–76. [Google Scholar]

- Verdon, Jean, ed. 1979. La Chronique de Saint-Maixent, 751–1140. Paris: Société d’Édition “Les Belles Lettres”. [Google Scholar]

- Villard, François. 1986. Un concile inconnu: Poitiers, 1082. Bulletin de la Société des Antiquaires de l’Ouest et des Musées de Poitiers 19: 587–97. [Google Scholar]

- Voyer, Cécile. 2020. La parole d’autorité et sa sacralisation par l’écrit: Les représentations d’assemblées dans quelques images du haut Moyen Âge. Cahiers de Civilisation Médiévale 63: 151–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Max. 2019. Economy and Society: A New Translation. Translated and Edited by Keith Tribe. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 341–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ziolkowski, Jan M., and Bridget K. Balint, eds. 2007. A Garland of Satire, Wisdom, and History: Latin Verse from Twelfth Century France (Carmina Houghtensiana). Cambridge: Houghton Library of the Harvard College Library. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brown, P.S. The Miracle of the Bloody Foreskin at the Council of Charroux in 1082: Legatine Authority, Religious Spectacle, and Charismatic Strategies of Canonical Reform in the Era of Gregory VII. Religions 2023, 14, 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030330

Brown PS. The Miracle of the Bloody Foreskin at the Council of Charroux in 1082: Legatine Authority, Religious Spectacle, and Charismatic Strategies of Canonical Reform in the Era of Gregory VII. Religions. 2023; 14(3):330. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030330

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrown, Peter Scott. 2023. "The Miracle of the Bloody Foreskin at the Council of Charroux in 1082: Legatine Authority, Religious Spectacle, and Charismatic Strategies of Canonical Reform in the Era of Gregory VII" Religions 14, no. 3: 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030330

APA StyleBrown, P. S. (2023). The Miracle of the Bloody Foreskin at the Council of Charroux in 1082: Legatine Authority, Religious Spectacle, and Charismatic Strategies of Canonical Reform in the Era of Gregory VII. Religions, 14(3), 330. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030330