Abstract

Prayer is a spiritual coping method that can be effective both in extraordinary, life-threatening circumstances and in ordinary, stressful situations. To be beneficial, it requires a bond with God or the divine based on trust and faith. The purpose of this study was to examine the mediated moderation model in which spiritual experiences moderate the link between prayer and stress, which in turn, is negatively related to the subjective well-being of Chilean students. The study’s participants were 177 students from Chile. The following tools were used: Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale, two measures regarding the quality of life and negative feelings from the World Health Organization Quality of Life—BREF, one tool verifying stress from the National Health Interview Survey and one-item scale in reference to frequency of praying. This study confirmed the mechanism underpinning the relationship between prayer and subjective well-being, as well as the benefits of a bond with God and the harmful role of stress in this relationship. When students more frequently felt God’s love and direction, prayer was negatively related to stress, which in turn, negatively predicted subjective well-being. For students with a poor bond with God and fewer spiritual experiences, prayer was positively linked with stress. This study confirms the benefits of a close, trusting bond with God or the divine and the detrimental effects of lacking a positive connection with God on students’ stress when students used prayer as a coping method. The practical implications of this study are also presented.

1. Introduction

Prayer is a spiritual practice that can help individuals better cope with stress (Pargament 1997). It happens not only in difficult life circumstances that threaten one’s health and life, as with cancer patients (Roh et al. 2018) and people with post-traumatic stress disorder (Exline et al. 2005; Tait et al. 2016), but also in non-clinical populations who confront stressful situations daily. For example, in a sample of undergraduate pharmacy students at the University of Khartoum, prayer was the most frequent strategy used to cope with academic stress (84.4%; Yousif et al. 2022).

Recent research has indicated that prayer related to health concerns is becoming more popular (Wachholtz and Sambamoorthi 2011). This was especially noticeable during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to a study by Boguszewski et al. (2020), during the COVID-19 pandemic, 21.3% of Poles researched declared that they had spent more time praying and engaging in other religious practices than previously.

Studies have shown that prayer is an effective strategy for coping with stress (Ai et al. 2005, 2008; Ferguson et al. 2010; Knabb and Vazquez 2018) and is a factor related to positive outcomes (Büssing et al. 2016; Chirico et al. 2020; Monroe and Jankowski 2016; Kraus et al. 2015; Lazar 2015; Paine and Sandage 2015; Tait et al. 2016; Wnuk 2021a, 2021b). For example, among Catholic teachers, two 30-min training sessions of prayer-reflection per week over 2 months led to decreased emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and improved job satisfaction (Chirico et al. 2020). Similarly, a randomized controlled trial of a two-week internet-based contemplative prayer program for Christians was shown to effectively reduce stress (Knabb and Vazquez 2018). Additionally, among Roman Catholic pastoral workers, private prayer was negatively correlated with anxiety, depression, and perceived stress and positively related to life satisfaction (Büssing et al. 2016).

Based on a review of research and previous conceptions, Breslin and Lewis (2008) have presented mechanisms underlying the link between prayer and health and well-being related to the placebo effect, engaging in health-related behaviors, diverting attention from health problems, and intervention by God or the divine.

For the spiritual mechanism underpinning the link between prayer and well-being to be effective, it requires effective communication and collaboration with God or the divine (Ferguson et al. 2010) that provides a sense of security, is based on trust, and represents a close bond with both God (Ai et al. 2005; You and Yoo 2016; Monroe and Jankowski 2016; Paine and Sandage 2015; Wnuk 2021a) and faith (Lazar 2015; Wnuk 2021b). According to research results without these requirements, prayer is not related to mental health and well-being. For example, in a sample from the US, prayer did not correlate with life satisfaction, optimism, and self-esteem. Conversely, the relationship between prayer and psychological well-being was moderated by attachment to God. Prayer was related to improvements in psychological well-being in a group of securely attached participants but not those who were insecurely attached to God (Bradshaw and Kent 2018). In Pössel et al. (2014)’s study the association of prayer frequency with depression was fully mediated by the trust-based beliefs about prayer (Pössel et al. 2014).

A person’s bond with God and the divine can moderate the link between prayer and positive outcomes. In a sample of female students from Poland, prayer was positively related to life satisfaction only in a group of participants with average and above-average positive religious coping (Wnuk 2021a). Among 206 graduate students from a Protestant-affiliated university in the United States, petitionary prayer involved hope’s interaction with spiritual instability: There was a weak negative correlation between spiritual instability and hope when the outcome of petitionary prayer was better than average compared to groups with average and above-average spiritual stability. The strongest negative correlation between hope and spiritual instability was noticed in students who prayed less than average (Paine and Sandage 2015). In a sample of Korean adults, the moderating role of spiritual support in the relationship between receptive prayer and subjective well-being was confirmed. Religious support strengthened the positive link between receptive prayer and subjective well-being among those who experienced moderate and high levels of spiritual support (You and Yoo 2016). Similar findings were noted for Polish students, as prayer predicted hope and meaning in life but only in individuals with the strongest faith. For participants with average and below-average levels of faith, prayer was unrelated to hope and meaning in life (Wnuk 2021b).

Bonding with God and believing in His support can affect how prayer as a coping method can predict levels of stress. For example, Roman Catholics who practiced a form of Christian meditation called centering prayer in ten weekly 2-h group sessions and individual practice twice per day increased their collaborative relationships with God and decreased stress (Ferguson et al. 2010). Furthermore, in Monroe and Jankowski’s longitudinal study (2016), increased perceived closeness with God (the Holy Spirit) as a result of receptive prayer intervention predicted lower distress post-test.

Based on the above, it was hypothesized that a connection with God or the divine (Underwood and Teresi 2002) would moderate the link between prayer and stress (Hypothesis 1). It was grounded in the transactional theory of stress (Lazarus and Folkman 1984, 1987) and prayer as a way of effectively dealing with stress but only in cases of effective communication with God or the divine; expectation of support from God; relief; and because of that perception, the stressor as a challenge not as a loss or threat (Lazarus and Folkman 1984).

Recent studies have confirmed that, among students, stress is a negative antecedent of mental health and well-being (Denovan and Macaskill 2017; Felt et al. 2021; Lopes and Nihei 2021; Schiffrin and Nelson 2010; Tran et al. 2022). For instance, in a sample of Brazilian undergraduate students, stress was negatively related to psychological well-being indicators such as environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relationships with others, and self-acceptance (Lopes and Nihei 2021). Moreover, in a study by Barbayannis et al. (2022), regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, and year of study, students who reported higher academic stress levels experienced diminished mental well-being. Similarly, in longitudinal research involving UK undergraduate students, stress positively predicted a negative effect (Denovan and Macaskill 2017). According to these results, a negative relationship between stress and subjective well-being is expected (Hypothesis 2).

Based on the above considerations, the presence of moderated mediation is anticipated. This means that prayer’s effect on a student’s connection with God or the divine should explain that student’s level of stress, which in turn, should be negatively related to their subjective well-being (Hypothesis 3). A connection with God or the divine was measured using daily spiritual experiences, which refer to ordinary spiritual movements and sensations (Underwood 2011). The Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (DSES) was designed to verify religiosity and spirituality as overlapping phenomena regarding spiritual experiences in connection with God, the divine, the holy, and transcendence. The scale also encompassed constructs such as awe, gratitude, mercy, a sense of connection with the transcendent, and compassionate love. Thus, this measure could also be used by nontheistic-inclined individuals (Underwood 2011), such as Chilean students who declared atheistic and agnostic approaches to religion but used prayer as a coping method, especially during spiritual struggles, which are not only experienced by religious people (Sedlar et al. 2018).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study sample encompassed university students from Chile. Questionnaires written in Spanish were distributed after classes and, upon completion, were collected by an overseas student with Polish grant funding. The participants were informed about anonymous participation in the study and their ability to resign at any time. A total of 180 questionnaires were distributed among the students; two students did not consent to participate in the research, and one student did not completely fill in the questionnaire; therefore, 177 students continued with the study. All remaining students graduated from secondary school and used the Spanish language. Men comprised 62% of participants and women comprised 38% of participants. The mean age of the students was 21.35 years. Of the participants, 55.37% identified as Roman Catholic, 10.96% identified as Evangelical, 8.3% identified as Seventh-day Adventists, 2.2% identified as Jehovah’s witnesses, 1.1% identified as Mormons, and 0.6% belonged to tribal religions. Atheists comprised 6.7%, agnostics comprised 7.57%, and non-affiliated individuals comprised 7.2%.

Power analysis was conducted to verify the adequacy sample size. For power equal to 0.95, medium size effect (f2 = 0.15), and the alpha = 0.05 the sample size result was 74. That meant that the research sample of 177 individuals is large enough.

Harman’s single-factor test was used to verify common method bias, confirming that the data does not bear a common method bias. One factor solution explained 34.13% variance, and it was less than an acceptable threshold, which is more than 40% (Podsakoff et al. 2003).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (DSES)

The DSES has good psychometric properties and measures a person’s relationship with God and the sacred. Depending on the population, the scale’s reliability ranges from α = 0.86 to 0.95 (Underwood 2011). The Spanish language version of this tool was used (Mayoral et al. 2013). Participants responded to 16 questions using a six-point scale ranging from 1 (never or almost never) to 6 (many times daily). The shorter six-item version of this measure was used, which possessed good psychometric properties (Wnuk 2022). The example item for the DSES is: “I feel deep inner peace or harmony”.

2.2.2. Prayer

On the frequency of prayer scale, students reported how often they prayed, with responses including never, sometimes, once monthly, once weekly, and every day.

2.2.3. Stress

Stress was assessed using a measure used in the National Health Interview Survey (2018). This tool consisted of six items regarding feelings being emotional manifestations of stress, such as hopelessness and irritation. One of the question was “During the past 30 days, how often did you feel restless or fidgety? Respondents answered on a 5-point scale (never, rarely, usually, often, and always).

2.2.4. Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being was measured using two indicators from The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL)-BREF (World Health Organization 2004) such as quality of life and negative feelings. In reference to their quality of life, respondents were asked to assess their lives by choosing from five possibilities: very poor, poor, neither poor nor good, good, and very good responding to the question “How would you rate your quality of life”?. Concerning negative feelings, participants responded about feeling or experiencing certain things in the last four weeks through the one question “How often do you have negative feelings such as blue mood, despair, anxiety, depression”?

2.3. Theoretical Model and Statistical Analyses

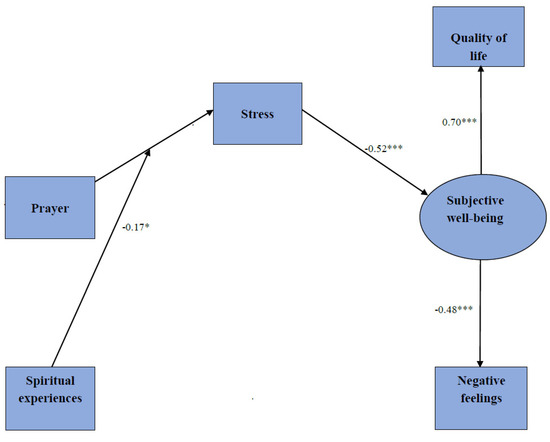

The conceptual model of the research is shown in Figure 1. This study tested the effect of prayer and connection with God, the divine, or divine transcendence on students’ stress and subjective well-being. A student’s relationship with God or the divine was examined via their spiritual experiences. The effect of prayer and connection with God on stress was expected to be similar to the effect of this relationship on subjective well-being through stress.

Figure 1.

Research model with path analysis results. Note. The standardized regression coefficients are presented. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001. (Source: the Author).

Subjective well-being was examined following Diener’s (1984) conception of it as a latent variable containing two indicators—cognitive evaluation of life measured by quality of life and affectivity through negative feelings. In contrast to Diener’s methodology, subjective well-being through positive affectivity was not considered.

Statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0. Path analysis, as part of structural equation modeling, was conducted in AMOS. The following fit model indices were used: comparative fit index, Tucker–Lewis index, goodness-of-fit index, root mean square error of approximation, and standard root mean square residuals. Because of the small sample size, bootstrapping was applied using 5000 resamples within a 90% bias-corrected confidence interval. The test statistic differs significantly from zero when the interval does not include 0 (Hayes 2018). To reduce potential multicollinearity problems, the variance inflation factor was used (O’Brien 2007).

3. Results

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptives statistics in a sample of Chilean students (n = 177).

Variance inflation factor values indicated the lack of a multicollinearity problem (O’Brien 2007). Table 2 presents the correlation coefficients between research variables.

Table 2.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients in a sample of Chilean students (n = 177).

Prayer was not statistically significantly correlated with subjective well-being, negative emotions, and stress; it was significant and moderately positively related to spiritual experiences. Spiritual experiences were weakly positively correlated with subjective well-being but not with stress and negative emotions. Stress was weakly negatively related to subjective well-being and moderately positively correlated with negative emotions. A statistically significant relationship between subjective well-being and stress was negative and moderate.

The research model with path analysis results is shown in Figure 1.

The model fit criteria values indicated that the model was well-fitted to the data: χ2(6) = 12.12; p = 0.06; and CMIN/df = 2.02. The comparative fit index was 0.95; the goodness-of-fit index was 0.98; the Tucker–Lewis index was 0.96; the NFI was 0.92; the root mean square error of approximation was 0.077 (90% CI [0.000, 0.014]); and the standard root mean square residual was 0.056.

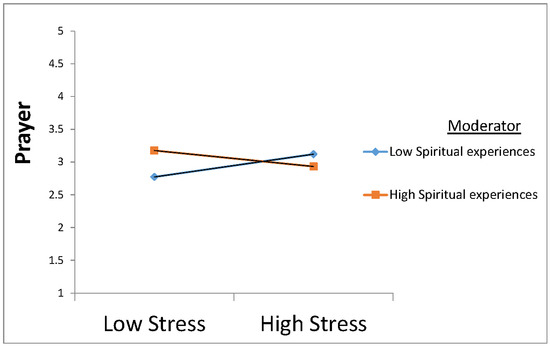

There was a statistically significant direct interactive effect of prayer and spiritual experiences on stress (90% CI [−0.272, −0.021], p = 0.05, β = −0.15), along with an irrelevant direct effect of prayer on stress (90% CI [−0.101, 0.182], p = 0.780, β = 0.03) and an irrelevant direct effect of spiritual experiences on stress (90% CI [−0.105, 0.217], p = 0.567, β = 0.05). The direct effects of stress on subjective well-being were significant (90% CI [0.352, 0.683], p < 0.000, β = 0.52), which was also true for the indirect, interactive effect of prayer and spiritual experiences on subjective well-being (90% CI [0.158, 0.013], p = 0.049, β = −0.08). The moderating effect of spiritual experiences in the relationship between prayer and stress is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Moderating effect of spiritual experiences in the relationship between prayer and stress in a sample of Chilean students (n = 177). (Source: author’s research).

4. Discussion

The purpose of the study was to explore and explain the mechanism underpinning the link between prayer and the subjective well-being of Chilean students. It was hypothesized that prayer as part of a student’s relationship with God or the divine explains that student’s level of stress, which in turn, negatively predicts their subjective well-being. According to Hypothesis 1, the role of a positive relationship with God or the divine as moderator of the association between prayer and stress was confirmed. Consistent with expectations, the positive link between prayer and subjective well-being was strengthened by a closer relationship with God or the divine manifested through more frequent experiences of God’s presence and feeling His love and direction. This corresponds with recent research emphasizing the conditional relationship between prayer and both positive and negative outcomes, which depends on a positive or negative connection with God or the divine (Ai et al. 2005; Ferguson et al. 2010; Monroe and Jankowski 2016; Paine and Sandage 2015; Wnuk 2021a, 2021b; You and Yoo 2016).

It was indicated that without spiritual growth, which results from developing a bond with God and the divine, prayer was a critical but insufficient factor for successfully coping with stress. Only students with a close relationship with God or the divine benefitted from praying when dealing with daily stress; students with weaker relationships with God experienced detrimental effects of prayer. In this group, prayer was positively related to stress. These findings are consistent with results from another recent study of students (Wnuk 2021a). Wnuk found that Polish students who reported trusting and faithful references to God and positive expectations of Him were connected with beneficial outcomes, as measured by life satisfaction but not by levels of stress. The present study differs from Wnuk’s (2021a) because this study assumes that the relationship between prayer and subjective well-being is more complex and requires not only a secure and trusting bond with God or the divine but also a lower level of stress as a consequence of that. Although the cited study did not use stress as a research variable, it confirmed that spiritual coping through collaborating with God during difficult times is an effective method of struggling with stress, which in turn, is positively tied with greater life satisfaction.

In this study, the negative link between stress and subjective well-being was examined within the second hypothesis. In line with expectations among Chilean students, stress was negatively correlated with subjective well-being. This corresponds with recent research outcomes related to students (Barbayannis et al. 2022; Lopes and Nihei 2021) and other samples (Denovan and Macaskill 2017; Felt et al. 2021; Schiffrin and Nelson 2010; Tran et al. 2022), indicating the negative link between these two constructs; this link likely exists regardless of the operationalization of these constructs, indicators, gender, education, religious affiliation, and cultural context. In light of these results, the third hypothesis, which connected the first and second hypotheses, was confirmed. This study found evidence of a relationship between prayer and subjective well-being and identified a relationship between stress and a person’s relationship with God or the divine. It was shown that depending on a person’s relationship with God and the divine, prayer can be positively or negatively indirectly related to subjective well-being, and stress mediates this link. This means that a secure, trusting, and faithful relationship with God or the divine via prayer protects Chilean students from stress, which in turn, is positively correlated with their subjective well-being. Conversely, lacking feelings of God’s presence, support, and direction when praying predicted higher levels of stress as a negative antecedent of subjective well-being.

These results can be interpreted within a transactional theory of stress and coping that considers coping a dynamic process between a stressor and person that involves perceiving and interpreting the source of stress (Lazarus and Folkman 1984, 1987). Prayer is one way of dealing with stress and can be employed in stressful situations. Regardless of the form of prayer during a stressful event, through prayer, individuals communicate with God or the divine, expecting support, relief, and positive outcomes. A close bond with God or the divine, where a person feels loved by God and expects His cooperation when dealing with stressors, can lead a person to perceive a stressful situation as a challenge rather than as a threat or loss; believing in positive solutions and activating coping resources can reduce stress (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Conversely, feeling the lack of God’s presence, feeling judged by God, and feeling abandoned by Him during prayer can cause a stressful event to be perceived as something threatening that cannot be positively resolved, which generates more stress. In difficult times, a bond with God can be a source of stability, predictability, and integrity that serves as a cognitive-emotional schema to interpret reality and life events as coherent and meaningful (McIntosh 1995).

In addition to confirming the psycho-spiritual mechanism underpinning the link between prayer and subjective well-being, some practical implications of the results of this study should be mentioned. Furthermore, the beneficial role of praying was observed in students with more frequent spiritual experiences, not only those who were religiously affiliated. Chilean students could be encouraged to use spiritual practices such as prayer and meditation to develop their spiritual spheres of life, through a bond with God in the case of believers and a relationship with the divine, other higher power, or transcendent reality for non-believers. This spirituality could offer support when confronting daily stress in a way that is indirectly related to life satisfaction. Some studies have already confirmed the beneficial influence of prayer on shaping a collaborative connection with God and reducing stress, among other positive outcomes (Büssing et al. 2016; Chirico et al. 2020; Ferguson et al. 2010; Knabb and Vazquez 2018).

5. Limitations and Future Research

Some limitations of this study should be emphasized. These results are limited to Chilean students; some declared religious denominations while others declared no religious affiliations. It was not a homogeneous group regarding religious affiliation consisting of representatives of different denominations such as Roman Catholics, Evangelicals, Seventh-day Adventists, Jehovah’s, etc.

The role of prayer and a bond with God or the divine in relation to well-being should be verified among other populations such as clinical patients and representatives of other cultural backgrounds with a wider range of ages. Since prayer is not only a spiritual practice but also a religious practice, it could be interesting to examine whether prayer in less religious nations could lead to positive outcomes and if a faithful and trusting connection with God or the divine, aside from prayer, is enough to achieve positive outcomes. Recent research has indicated a positive relationship between religiosity and well-being in religious nations and found a lack of religiosity plus negative well-being in secular countries (Diener et al. 2011; Stavrova et al. 2013).

It is possible that a country’s level of religiosity moderates the relationship between prayer and well-being. A comparative study of very religious nations and strongly secular countries that apply secular spiritual practices such as meditation could verify this assumption and yield interesting results. Furthermore, other variables such as personality traits, religious orientation, religious coping, attachment to God, age, gender, financial status, or alcohol consumption can influence the relationship between prayer and well-being (Wnuk 2021b; Wnuk et al. 2022). For example, in a study of Polish female students representing the Roman Catholic affiliation, prayer positively correlated with life satisfaction only among students with average and above-average positive religious coping (Wnuk 2021a). Additionally, Wnuk (2021b) has found that in a group of Polish students with the strongest religious faith, prayer is positively connected with meaning in life and negatively with the tendency to revenge, but these relationships among students with average and less than average frequency of prayer were insignificant. Due to students as a research sample characterized by similar age, this variable was controlled in this study. Gender was not a controlled variable in this research.

Another limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design. This study also uses a methodology that does not indicate the direction between research variables, so the results cannot be interpreted from a cause-and-effect perspective.

Funding

This study was funded by author sources.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to non-potential harming influence.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy of the participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Ai, Amy L., Terrence N. Tice, Bu Huang, Willard L. Rodgers, and Steven F. Bolling. 2008. Types of prayer, optimism, and well-being of middle-aged and older patients undergoing open-heart surgery. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 11: 131–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Amy L., Terrence N. Tice, Christopher Peterson, and Bu Huang. 2005. Prayers, spiritual support, and positive attitudes in coping with the September 11 national crisis. Journal of Personality 73: 763–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbayannis, Georgia, Mahindra Bandari, Xiang Zheng, Humberto Baquerizo, Keith W. Pecor, and Xue Ming. 2022. Academic stress and mental well-being in college students: Correlations, affected groups, and COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 886344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguszewski, Rafał, Marta Makowska, Marta Bożewicz, and Monika Podkowińska. 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on religiosity in Poland. Religions 11: 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, Matt, and Blake Victor Kent. 2018. Prayer, attachment to god, and changes in psychological well-being in later life. Journal of Aging and Health 30: 667–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslin, Michael J., and Christopher Alan Lewis. 2008. Theoretical models of the nature of prayer and health: A review. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 11: 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, Arndt, Eckhard Frick, Christopher Jacobs, and Klaus Baumann. 2016. Health and life satisfaction of Roman Catholic pastoral workers: Private prayer has a greater impact than public prayer. Pastoral Psychology 65: 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, Francesco, Manoj Kumar Sharma, Salvatore Zaffina, and Nicola Magnavita. 2020. Spirituality and prayer on teacher stress and burnout in an Italian cohort: A pilot, before-after controlled study. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denovan, Andrew, and Ann Macaskill. 2017. Stress and subjective well-being among first year UK undergraduate students. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being 18: 505–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed. 1984. Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin 95: 542–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, Louis Tay, and David Gershom Myers. 2011. The religion paradox: If religion makes people happy, why are so many dropping out? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 101: 1278–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exline, Julie J., Joshua M. Smyth, J. Claire Gregory, Jill R. Hockemeyer, and Heather E. Tulloch. 2005. Religious framing by individuals with PTSD when writing about traumatic experiences. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 15: 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felt, John M., Sarah Depaoli, and Jitske Tiemensma. 2021. Stress and information processing: Acute psychosocial stress affects levels of mental abstraction. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping 34: 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, Jane, Eleanor Walker Willemsen, and MayLynn V. Castaneto. 2010. Centering prayer as a healing response to everyday stress: A psychological and spiritual process. Pastoral Psychology 59: 305–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2018. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (Methodology in the Social Sciences), 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knabb, Joshua J., and Veola E. Vazquez. 2018. A randomized controlled trial of a 2-week internet-based contemplative prayer program for Christians with daily stress. Spirituality in Clinical Practice 5: 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, Rachel, Scott A. Desmond, and Zachary D. Palmer. 2015. Being thankful: Examining the relationship between young adult religiosity and gratitude. Journal of Religion and Health 4: 1331–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, Aryeh. 2015. The relation between prayer type and life satisfaction in religious Jewish men and women: The moderating effects of prayer duration and belief in prayer. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 25: 211–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, Richard S., and Susan Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, Richard S., and Susan Folkman. 1987. Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of Personality 1: 141–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, Adriana Rezende, and Oscar Kenji Nihei. 2021. Depression, anxiety and stress symptoms in Brazilian university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Predictors and association with life satisfaction, psychological well-being and coping strategies. PLoS ONE 16: e0258493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayoral, Edwin G., Lynn G. Underwood, Francisco A. Laca, and Juan Carlos Mejía. 2013. Validation of the Spanish version of Underwood’s Daily Spiritual Experience Scale in Mexico. International Journal of Hispanic Psychology 6: 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, Daniel N. 1995. Religion-as-schema, with implications for the relation between religion and coping. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 5: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, Natasha, and Peter J. Jankowski. 2016. The effectiveness of a prayer intervention in promoting change in perceived attachment to God, positive affect, and psychological distress. Spirituality in Clinical Practice 3: 237–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Interview Survey. 2018. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- O’Brien, Robert M. 2007. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality & Quantity: International Journal of Methodology 41: 673–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paine, David R., and Steven J. Sandage. 2015. More prayer, less hope: Empirical findings on spiritual instability. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health 17: 223–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 1997. The Psychology of Religion and Coping. Theory, Research, Practice. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, Jeong-Yeon Lee, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pössel, Patrick, Stephanie Winkeljohn Black, Annie C. Bjerg, Benjamin Jeppsen, and Don T. Wooldridge. 2014. Do trust-based beliefs mediate the associations of frequency of private prayer with mental health? A cross-sectional study. Journal of Religion and Health 53: 904–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, Soonhee, Catherine E. Burnette, and Yeon-Shim Lee. 2018. Prayer and faith: Spiritual coping among american indian women cancer survivors. Health & Social Work 43: 185–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffrin, Holly H., and S. Katherine Nelson. 2010. Stressed and happy? Investigating the relationship between happiness and perceived stress. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being 11: 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlar, Aaron Edward, Nick Stauner, Kenneth I. Pargament, Julie J. Exline, Joshua B. Grubbs, and David F. Bradley. 2018. Spiritual struggles among atheists: Links to psychological distress and well-being. Religions 9: 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrova, Olga, Detlef Fetchenhauer, and Thomas Schlösser. 2013. Why are religious people happy? The efect of the social norm of religiosity across countries. Social Science Research 42: 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, Rhondie N., Joseph M. Currier, and J. Irene Harris. 2016. Prayer coping, disclosure of trauma, and mental health symptoms among recently deployed United States veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 26: 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Nguyen Toan, Jessica Franzén, Françoise Jermann, Serge Rudaz, Guido Bondolfi, and Paolo Ghisletta. 2022. Psychological distress and well-being among students of health disciplines in Geneva, Switzerland: The importance of academic satisfaction in the context of academic year-end and COVID-19 stress on their learning experience. PLoS ONE 17: e0266612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Underwood, Lynn G. 2011. The daily spiritual experience scale: Overview and results. Religions 2: 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, Lynn G., and Jeanne A. Teresi. 2002. The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale: Development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 24: 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wachholtz, Amy, and Usha Sambamoorthi. 2011. National trends in prayer use as a coping mechanism for health concerns: Changes from 2002 to 2007. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 3: 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wnuk, Marcin. 2021a. Religion and life satisfaction of polish female students representing Roman Catholic affiliation: Test of empirical model. Religions 12: 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wnuk, Marcin. 2021b. Links between faith and some strengths of character: Religious commitment manifestations as a moderators. Religions 12: 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wnuk, Marcin. 2022. The mechanism underlying the relationship between the spiritual struggles and life satisfaction of Polish codependent individuals participating in Al-Anon—pilot study. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health. Advance online publication. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/19349637.2022.2124141 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Wnuk, Marcin, Maciej Wilski, Małgorzata Szcześniak, Halina Bartosik-Psujek, Katarzyna Kapica-Topczewska, Joanna Tarasiuk, Agata Czarnowska, Alina Kułakowska, Beata Zakrzewska-Pniewska, Waldemar Brola, and et al. 2022. Model of the Relationship of Religiosity and Happiness of Multiple Sclerosis Patients from Poland: The Role of Mediating and Moderating Variables. Religions 13: 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2004. The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL)—BREF. 2012 Revision. World Health Organization. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/77773 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- You, Sukkyung, and Ji Eun Yoo. 2016. Prayer and subjective well-being: The moderating role of religious support. Archiv für Religionspsychologie/Archive for the Psychology of Religion 38: 301–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, Mariam, Ahmed H. Arbab, and Bashir Alsiddig Yousef. 2022. Perceived academic stress, causes, and coping strategies among undergraduate pharmacy students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Advances in Medical Education and Practice 13: 189–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).