Religiosity and the Perception of Interreligious Threats: The Suppressing Effect of Negative Emotions towards God

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Religiosity as Multidimensional

1.2. Religiosity and Emotions towards God

1.3. Perceptions of Interreligious Threats

1.4. Research Objectives and Hypotheses

2. Research Methods and Instruments

2.1. Ethics and Consent

2.2. Research Instruments

2.3. Participants

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Bivariate Correlational Analysis

3.3. Regression Analysis

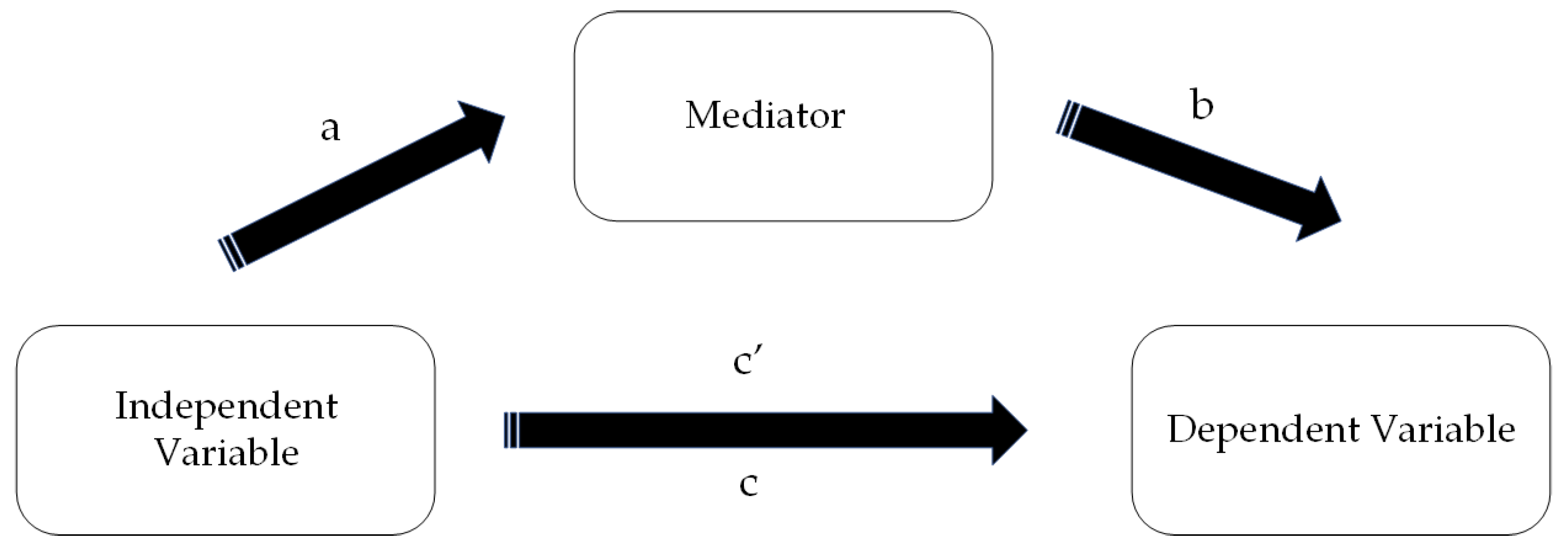

3.4. Mediation Analysis

- EtG-neg has a statistically significant bivariate correlation with both CRS and EtG-pos, but it has no statistically significant bivariate correlation with the outcome variable.

- The inclusion of EtG-neg into the regression models resulted in an improved model with statistically significant change in R2.

- The effect of EtG-neg bears an opposite sign from that of CRS and EtG-pos.

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aditya, Yonathan, Ihan Martoyo, Jessica Ariela, and Rudy Pramono. 2022. Religiousness and Anger toward God: Between Spirituality and Moral Community. Religions 13: 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, Yonathan, Ihan Martoyo, Jessica Ariela, and Rudy Pramono. 2020. Does Anger toward God Moderate the Relationship Between Religiousness and Well-Being? Annals of Psychology 23: 375–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, Douglas G., and J. Martin Bland. 1995. Statistics Notes: The Normal Distribution. BMJ 310: 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- AR, Zurairi. 2019. Only Hell Awaits If Non-Muslims Lead, Hadi Says in Piece Calling for Islamic Supremacy. Malay Mail. January 8. Available online: https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2019/01/08/only-hell-awaits-if-non-muslims-lead-hadi-says-in-piece-calling-for-islamic/1710372 (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Baetz, Marilyn, Ronald Griffin, Rudy Bowen, Harold G. Koenig, and Eugene Marcoux. 2004. The Association Between Spiritual and Religious Involvement and Depressive Symptoms in a Canadian Population. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 192: 818–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergan, Anne, and Jasmin Tahmeseb McConatha. 2001. Religiosity and Life Satisfaction. Activities, Adaptation & Aging 24: 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. 2022. Key Findings: Population and Housing Census of Malaysia, 2020. Available online: https://cloud.stats.gov.my/index.php/s/BG11nZfaBh09RaX#pdfviewer (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Edara, Inna R., Fides del Castillo, Gregory S. Ching, and Clarence D. del Castillo. 2021. Religiosity, Emotions, Resilience, and Wellness during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Study of Taiwanese University Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 6381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, Lisa M., Regina H. Lapp-Rincker, Jeana L. Magyar-Moe, Jason D. Rehfeldt, Jamie A. Ryder, Jill C. Brown, and Shane J. Lopez. 2002. A Positive Relationship Between Religious Faith and Forgiveness: Faith In The Absence Of Data? Pastoral Psychology 50: 147–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, Julie J., and Eric D. Rose. 2013. Religious And Spiritual Struggles. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 379–97. [Google Scholar]

- Exline, Julie J., Crystal L. Park, Joshua M. Smyth, and Michael P. Carey. 2011. Anger toward God: Social-Cognitive Predictors, Prevalence, and Links with Adjustment to Bereavement and Cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100: 129–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferran, Ingrid Vendrell. 2019. Religious Emotion as a Form of Religious Experience. Journal of Speculative Philosophy 22: 78–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, Asghar, and Saleh Zahediasl. 2012. Normality Test for Statistical Analysis: A Guide for Non-Statisticians. International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism 10: 496–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glock, Charles Y., and Rodney Stark. 1965. Religion and Society in Tension. San Francisco: Rand McNally. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan, Mathias Allemand, and Odila W. Huber. 2011. Forgiveness by God and Human Forgivingness: The Centrality of the Religiosity Makes the Difference. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 33: 115–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan, and Odila W. Huber. 2012. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions 3: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan, and Matthias Richard. 2010. The Inventory of Emotions towards God (EtG): Psychological Valences and Theological Issues. Review of Religious Research 52: 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kanas, Agnieszka, Peer Scheepers, and Carl Sterkens. 2015. Interreligious Contact, Perceived Group Threat, and Perceived Discrimination: Predicting Negative Attitudes among Religious Minorities and Majorities in Indonesia. Social Psychology Quarterly 78: 102–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koenig, Harold G. 2012. Religion, Spirituality, and Health: The Research and Clinical Implications. International Scholarly Research Network Psychiatry 2012: 278730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lassi, Stefano, and Daniele Mugnaini. 2015. Role of Religion and Spirituality on Mental Health and Resilience: There is Enough Evidence. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience 17: 661–63. [Google Scholar]

- Makashvili, Ana, Irina Vardanashvili, and Nino Javakhishvili. 2018. Testing Intergroup Threat Theory: Realistic and Symbolic Threats, Religiosity and Gender as Predictors of Prejudice. Europe’s Journal of Psychology 14: 464–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malhi, Amrita. 2015. Like a Child with Two Parents: Race, Religion and Royalty on the Siam-Malaya Frontier, 1895–1902. The Muslim World 105: 472–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez de Pisón, Ramón. 2022. Religion, Spirituality and Mental Health: The Role of Guilt and Shame. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFatter, Robert M. 1979. The Use of Structural Equation Models in Interpreting Regression Equations Including Suppressor and Enhancer Variables. Applied Psychological Measurement 3: 123–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohd Sani, Mohd Azizuddin, and Dina Diana Abdul Hamed Shah. 2011. Freedom of Religious Expression in Malaysia. Journal of International Studies 7: 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzaffar, Chandra. 1996. Accommodation and Acceptance of Non-Muslim Communities within the Malaysian Political System: The Role of Islam. American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences 13: 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Darrelle. 2022. Parti Islam Se-Malaysia’s Rise in GE15: Is Malaysia Becoming More Conservative? Channel News Asia. November 21. Available online: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/asia/malaysia-ge15-elections-islamic-party-pas-conservative-3089301 (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Palansamy, Yiswaree. 2022. PAS Man Apologises for Saying Those who Vote BN, Pakatan Will Go to Hell. Malay Mail. November 11. Available online: https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2022/11/11/pas-man-apologises-for-saying-those-who-vote-bn-pakatan-will-go-to-hell/38993 (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Pandey, Shanta, and William Elliott. 2010. Suppressor Variables in Social Work Research: Ways to Identify in Multiple Regression Models. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research 1: 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pew Research Center. 2018. The Age Gap in Religion Around the World. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, June 13. [Google Scholar]

- Saroglou, Vassillis. 2011. Believing, Bonding, Behaving, and Belonging: The Big Four Religious Dimensions and Cultural Variation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42: 1320–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Star. 2022. Muhyiddin’s Christianisation Agenda Claim is Dangerous, Says CCM. November 28. Available online: https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2022/11/18/muhyiddin039s-christianisation-agenda-claim-is-dangerous-says-ccm (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Stark, Richard, and Charles Y. Glock. 1968. American Piety: The Nature of Religious Commitment. Los Angeles: Berkeley University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rye, Mark S., Dawn M. Loiacono, Chad D. Folck, Brandon T. Olszewski, Todd A. Heim, and Benjamin P. Madia. 2001. Evaluation of the Psychometric Properties of Two Forgiveness Scales. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues 20: 260–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, Walter G., Oscar Ybarra, and Kimberly Rios Morrison. 2009. Intergroup Threat Theory. In Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination. Edited by Todd D. Nelson. New York: Psychology Press, pp. 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Szcześniak, Małgorzata, Grażyna Bielecka, Iga Bajkowska, Anna Czaprowska, and Daria Madej. 2019. Religious/Spiritual Struggles and Life Satisfaction among Young Roman Catholics: The Mediating Role of Gratitude. Religions 10: 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tan, Lee Ooi. 2022. Conceptualizing Buddhisization: Malaysian Chinese Buddhists in Contemporary Malaysia. Religions 13: 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Frequency (f) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–25 | 238 | 91.5 |

| 26–35 | 18 | 6.9 | |

| 36–45 | 3 | 1.2 | |

| 46–55 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| >55 | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Total | 260 | 100 | |

| Religion | Islam | 67 | 25.8 |

| Christianity (Protestants and Catholics) | 64 | 24.6 | |

| Chinese religions (Buddhism and Taoism) | 73 | 28.1 | |

| Indian religions (Hinduism and Sikhism) | 10 | 3.8 | |

| No religion | 45 | 17.3 | |

| Others | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Total | 260 | 100 | |

| Ethnicity | Chinese | 157 | 60.4 |

| Indian | 23 | 8.8 | |

| Malay | 45 | 17.3 | |

| Indigenous people in Peninsular Malaysia | 3 | 1.2 | |

| Others | 32 | 12.3 | |

| Total | 260 | 100 |

| Scales | Min | Max | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | No. of Items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.CRS | 1.1333 | 5.0000 | 3.3269 | 1.0156 | −0.236 | −1.094 | 0.952 | 15 |

| 2.EtG-pos | 1.0000 | 5.0000 | 3.3641 | 1.2201 | −0.564 | −0.748 | 0.971 | 9 |

| 3.EtG-neg | 1.0000 | 5.0000 | 2.3242 | 0.9636 | 0.581 | −0.227 | 0.893 | 7 |

| 4.Threat | 1.0000 | 5.0000 | 2.1451 | 0.9565 | 0.716 | 0.050 | 0.931 | 12 |

| 1 | 1a | 1b | 1c | 1d | 1e | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.CRS | 1 | ||||||||

| 1a IDL | 0.719 *** | 1 | |||||||

| 1b ITL | 0.589 *** | 0.402 *** | 1 | ||||||

| 1c PUB | 0.740 *** | 0.571 *** | 0.506 *** | 1 | |||||

| 1d PRI | 0.786 *** | 0.616 *** | 0.488 *** | 0.618 *** | 1 | ||||

| 1e EXP | 0.745 *** | 0.626 *** | 0.410 *** | 0.549 *** | 0.658 *** | 1 | |||

| 2.EtG-pos | 0.700 *** | 0.625 *** | 0.437 *** | 0.582 *** | 0.659 *** | 0.659 *** | 1 | ||

| 3.EtG-neg | 0.276 *** | 0.260 *** | 0.138 ** | 0.247 *** | 0.280 *** | 0.300 *** | 0.268 *** | 1 | |

| 4.Threat | −0.130 ** | −0.144 *** | −0.07 | −0.13 ** | −0.137 ** | −0.085 | −0.136 ** | 0.051 | 1 |

| Predictors | β (Model 1) | β (Model 2) |

|---|---|---|

| CRS | −0.161 ** | −0.236 *** |

| EtG-neg | 0.194 ** | |

| R2 | 0.029 | 0.061 |

| ΔR2 | 0.032 ** | |

| EtG-pos | −0.142 ** | −0.208 *** |

| EtG-neg | 0.202 ** | |

| R2 | 0.033 | 0.067 |

| ΔR2 | 0.034 ** |

| Paths | a | b | c | c’ | ab | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | |

| 1. CRS—EtG-neg—Threat | 0.3849 *** | 0.5400 | 0.1942 ** | 0.6560 | −0.1613 ** | 0.0578 | −0.236 *** | 0.0623 | 0.0747 | 0.0286 |

| 2. IDL—EtG-neg—Threat | 0.3062 *** | 0.0479 | 0.1779 ** | 0.0648 | −0.135 ** | 0.0505 | −0.1895 *** | 0.0536 | 0.0545 | 0.0222 |

| 3. ITL—EtG-neg—Threat | 0.2040 ** | 0.0644 | 0.1111 | 0.0626 | −0.0747 | 0.065 | −0.0974 | 0.0660 | 0.0227 | 0.0163 |

| 4. PUB—EtG-neg—Threat | 0.2509 *** | 0.0438 | 0.1742 ** | 0.0632 | −0.1359 ** | 0.0453 | −0.1796 *** | 0.0574 | 0.0437 | 0.0181 |

| 5. PRI—EtG-neg—Threat | 0.3108 *** | 0.0432 | 0.2054 ** | 0.0653 | −0.145 ** | 0.0462 | −0.2089 *** | 0.0497 | 0.0638 | 0.0239 |

| 6. EXP—EtG-neg—Threat | 0.3155 *** | 0.0443 | 0.1633 * | 0.0666 | −0.0831 | 0.0479 | −0.1346 ** | 0.0518 | 0.0515 | 0.0235 |

| 7. EtG-pos—EtG-neg—Threat | 0.3261 *** | 0.0448 | 0.2019 ** | 0.0657 | −0.1419 ** | 0.048 | −0.2077 *** | 0.0519 | 0.0658 | 0.0239 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lam, D.Y.P.; Koh, K.S.; Gan, S.W.; Sow, J.T.Y. Religiosity and the Perception of Interreligious Threats: The Suppressing Effect of Negative Emotions towards God. Religions 2023, 14, 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030366

Lam DYP, Koh KS, Gan SW, Sow JTY. Religiosity and the Perception of Interreligious Threats: The Suppressing Effect of Negative Emotions towards God. Religions. 2023; 14(3):366. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030366

Chicago/Turabian StyleLam, Dorcas Yarn Pooi, Kai Seng Koh, Siew Wei Gan, and Jacob Tian You Sow. 2023. "Religiosity and the Perception of Interreligious Threats: The Suppressing Effect of Negative Emotions towards God" Religions 14, no. 3: 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030366

APA StyleLam, D. Y. P., Koh, K. S., Gan, S. W., & Sow, J. T. Y. (2023). Religiosity and the Perception of Interreligious Threats: The Suppressing Effect of Negative Emotions towards God. Religions, 14(3), 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030366