Desiring the Sweet Perfume of Closeness in the Oscillating Tawajjuh of the Letter Rāʾ

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The rāʾ is in the station of lovers together, beloved,always in the abode of his good fortune, never forsaken.1

2. Structures

3. Ibn ʿArabī’s Alphabetic Cosmography

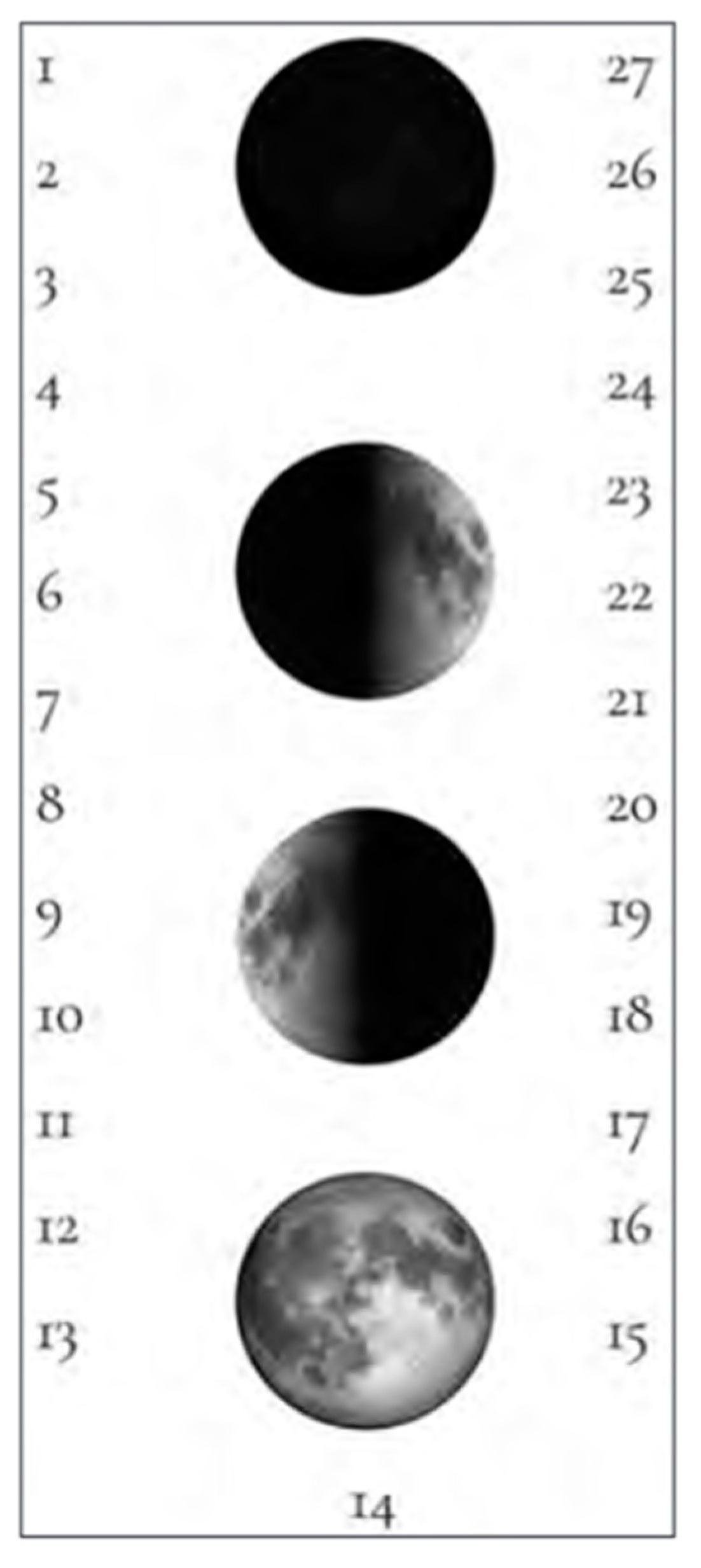

‘According to us, from the door of kashf—when some of them come out from being…the first is more elevated (ashraf)30 than the second; and it is this way for each subsequent one until the halfway mark….The last and the first are the most elevated that come out.…and in this way up to the night of the new moon during the first of the month and his setting during the end of the month. The waning moon night is then equal to the full moon (badr) night—so understand.’31

‘A wāw: You alone, more holy than my being,and more precious!He is a spirit completed (rūḥ mukkamal),and he is a secret six-fold…’47

4. Word Polysemy

‘…oscillate (raddada) me between a ‘hopeful longing’ for You and a ‘reverent fear’ of You. Restore (radda) to me the cloak (ridāʾ) of satisfaction (riḍwān) and bring me to the wellsprings (mawārid) of the welcome.’

5. The Poem and the Prayer

5.1. Poem: Among Them Is the Letter Rā (wa-min dhālika ḥarf al-rāʾ)56

‘The rāʾ is in the station of lovers together, beloved (maqām al-wiṣāl),always in the abode of his good fortune, never forsaken.One time he says, ‘I am the single one (al-waḥīd),and I do not see other than me!’ And another time, ‘O me, you were never ignored!’If your heart were with your Lord in this way,you would be someone brought so close (muqarraba), and beloved, and most complete (akmal).’

5.2. Prayer: The Orientation of the Unpointed Letter Rāʾ (tawajjuh ḥarf al-rāʾ al-muhmala)61

‘O my Lord (rabb), instruct me (rabba) with the subtle benevolence (laṭīf) of Your Lordliness (rubūbiyya), as one who is conscious of being in total need (muftaqir) of You should be instructed (tarbiya), as one who never claims to be independent of You. Watch over me with your eye of attentive care (riʿāya), vigilantly protecting (muraqaba) me from all the knocks that may befall me, or anything that may afflict me or cause me to be troubled at any moment or in any perception, or that may write one of the lines upon the tablet of my destiny. Provide me with the ease (rāḥa) of intimacy with You and raise (rāqqa) me to the station of closeness (maqam al-qurb) to You. Revive (rawwiḥ) my spirit (rūḥ) with Your remembrance and oscillate (raddada) me between a ‘hopeful longing’ (raghab) for You and a ‘reverent fear’ (rahab) of You.62 Restore (radda) to me the cloak (ridāʾ) of satisfaction (riḍwān) and bring me to the wellsprings (mawārid) of the welcome (qabūl). Grant me Mercy (raḥma) from You, re-establishing harmony in my disorder, rectifying where I am deviating, perfecting where I am lacking, restraining me when I am astray and guiding my perplexity (ḥāʾira).Indeed, You are ‘Lord of every thing’ and its instructor (murabbīh). You mercify (raḥim) the essences [of all beings] and You elevate (rafaʿ) the degrees. Your closeness (qurb) is the joy (rawḥ) of the spirits (arwāḥ), and the perfumed sweetness (rayḥān) of joyous satisfaction (irtiyāḥ); the epitome of true prosperity, and the repose (rāḥa) of all those who are at ease (murtāḥ).May You be blessed, Lord of lords. Liberator of slaves (riqāb)!63 Lifter of suffering! You ‘embrace everything in mercy (raḥma) and in knowledge.’64 You forgive wrongdoing with loving tenderness and clemency. You are the most kind (raʾūf), the compassionate (raḥīm).May the blessing of God be upon our master Muhammad, the prophet, and upon his family and companions.’

‘ʿIbn Thābit said, “… My eyes and my breasts are impassioned by sleeplessness;tears fall on my place of weeping and my place of pooling.”Now, my mother was illiterate, related to the Anṣār, so I say:For this I made his narrative a rāʾ, which…The choosing one alluded to the breath whichcame to him from Yemen, at the fated moment.’

‘”Through what have you known God?” He replied, “Through the fact that He brings opposites together.” So every entity qualified by existence is it/not it. The whole cosmos is He/not He. The Real manifest through form is He/not He. He is the limited who is not limited, the seen who is not seen.’93

‘One time (waqtan) he says, ‘I am the single one,and I do not see other than me!’ And another time (waqtan), ‘O me, you never ignored!’’

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 1/216; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020a), The Openings Book 1 & 2, p. 231. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | It is beyond the scope of this article to conduct authorship analysis of Sufi prayer literature. For analysis of misattribution in Sufi texts, see e.g., Ibn ʻArabī et al. (2021), Prayers for the Week, pp. 1, 14, 20–22; Beneito and Hirtenstein (2021), Patterns of Contemplation; S. Taji-Farouki, A Prayer for Spiritual Elevation and Protection. Oxford: Anqa, 2006; M. Ebstein and S. Sviri, “The So-Called Risālat al-Ḥurūf (Epistle on Letters) Ascribed to Sahl Al-Tustarī and Letter Mysticism in Al-Andalus,” in Journal Asiatique 299, no. 1 (2011): 213–70. |

| 4 | Quran 7:55. The term munājā describes a petition to be brought nearer to God. By engaging in supererogatory acts, the supplicant exercises a free choice, thus, he or she is a voluntary slave (ʿabd) or a slave by free choice. |

| 5 | |

| 6 | Ibn ʿArabī states that alif is not a letter as according to the knowledge gained by, ‘One who smells the truths,’ unlike, the opinion of the general population whom, he says, considers it as a letter. In Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 1/207; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020a), The Openings Books 1 & 2, p. 219). |

| 7 | See note 5. |

| 8 | |

| 9 | Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 1/207–32; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020a), The Openings Books 1 & 2, pp. 219–59. |

| 10 | Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 1/508; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020b), The Openings Books 3 & 4, p. 36. |

| 11 | Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt III, pp. 526–27 cited in Rašić (2021), The Written World, p. 82. |

| 12 | Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 1/546; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020b), The Openings Book 3 & 4, p. 113; Morris (2007), The Reflective Heart, p. 69. |

| 13 | |

| 14 | |

| 15 | |

| 16 | |

| 17 | Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 1/193; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020a), The Openings Books 1 & 2, p. 190. |

| 18 | |

| 19 | |

| 20 | Unveiling; kashf is a type of direct experience through which knowledge of Reality is revealed to the heart of the servant (ʿabd) and lover, in Amstrong, Sufi Terminology, p. 109. |

| 21 | Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 1/191–92; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020a), The Openings Books 1 & 2, pp. 187–88; Gril (2004), “The Science of Letters,” p. 163. |

| 22 | Rašić (2021) citing Ibn ʿArabī’s works that deals with the science of letters, The Meccan Revelations (al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya), Bezels of Wisdom (Fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam), The Book of Alif (Kitāb al-Alif), The Book of the Letter Bāʾ (Kitāb al-Bāʾ), The Book of Mīm, Wāw and Nūn (Kitāb al-Mīm wa-l-Wāw wa-l-Nūn) and The Book of Majesty (Kitāb al-Jalāla) in The Written World, p. 7. |

| 23 | Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020a), The Openings Books 1 & 2, p. 171; Gril (2004), “The Science of Letters,” pp. 155–56. |

| 24 | |

| 25 | The invocation bismiʾllāhi al-raḥmān al-raḥīm. |

| 26 | The Quranic chapters where the letter rāʾ appears in the combination of ʾAlif Lām Rāʾ are: “Yūnus,” “Hud,” “Yūsuf,” “Ibrāhīm,” “al-Ḥijr”; and once in ʾAlif Lām Mīm Rāʾ in the chapter “Al-Raʿd.” |

| 27 | Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 1/191; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020a), The Openings Books 1 & 2, p. 186. |

| 28 | “The Heights”, Al-ʿArāf, as described in the chapter of that name in Quran 7: 46. |

| 29 | |

| 30 | Winkel translates ashraf as ‘panoramic’ which conveys a sense of height and extensive view, as well as continuous unfolding phases, The Openings Books 1&2, p. 276. |

| 31 | Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020a), The Openings Books 1 & 2, p. 276. The word ‘being’ is italicized in the original translation. |

| 32 | See “Symbolism of wāw” in Ibn ʻArabī et al. ([2000] 2008), The Seven Days, pp. 117, 119–23. For extensive discussion on the wāw see Beneito and Hirtenstein (2021), Patterns of Contemplation. |

| 33 | Quṭb (pl. aqṭāb) literally meaning pole or axis generally refers to the highest spiritual station of the friends of God (awliyā). The quṭb is the central axis around which the spiritual hierarchy revolves, and their presence is believed to be essential for the spiritual well-being and guidance of the world. |

| 34 | |

| 35 | |

| 36 | |

| 37 | Quran 50:16. |

| 38 | Ibn ʻArabī et al. ([2000] 2008), The Seven Days, p. 15. For more on the significance of number twenty-eight see Rašić (2021), The Written World, p. 76. |

| 39 | |

| 40 | Beneito and Hirtenstein (2021), Patterns of Contemplation, 38, note 29, p. 171. The circle or the two arc is symbolized by the letter nūn, which the authors discuss extensively throughout the book. |

| 41 | While we emphasize the association between the letter rāʾ with the full moon, the luminous letters and the number fourteen, we also note that rāʾ is classified as a ‘sun letter’ and wāw belongs to the ‘moon letter’ according to the grammatical categorization of the Arabic alphabet. This categorization entails an equal division of fourteen sun letters (ḥurūf shamsiyya) and fourteen ‘moon letters’ (ḥurūf qamariyya). From a grammatical standpoint, these two groups primarily differ in their treatment of the definite article ‘al-’ in spoken Arabic. Sun letters undergo assimilation with the definite article ‘al-‘, resulting in the replacement of the ‘l’ (lām) sound in ‘al-‘ with the respective sun letter. In contrast, moon letters do not trigger this assimilation, and the pronunciation of ‘al-‘ remains unchanged. It is undoubtedly intriguing to explore the intricate connections that may exist between the luminous and dark letters, the sun and moon letters, and the number fourteen. These various references invite us to reconsider the logic and paradox inherent in each distinct mode of discourse they represent. However, this examination exceeds the scope of the present article. |

| 42 | Beneito and Hirtenstein (2021), Patterns of Contemplation, p. 9; the authors discuss the significance of number fourteen. |

| 43 | |

| 44 | In traditional Arabic poetry, the lines carry the same final consonant until the end of the poem, called rawī, for rhyming effect. |

| 45 | A single line of poetry consisting of two hemistichs or half lines, is called a bayt (pl. buyūt), a metrical unit of poetry in Arabic, Urdu, Indian and Sindhi traditions. Corresponds to a line in English poetry. |

| 46 | Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 8/48; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel, “On Maʿrifah of an Alighting Place of the Moon—the Hilāl, the Badr; from the Muḥammadī Presence,” The Openings Revealed in Makkah (New York: Pir Press, forthcoming). |

| 47 | Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 1/226; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020a), The Openings Books 1 & 2, p. 247. |

| 48 | |

| 49 | |

| 50 | |

| 51 | |

| 52 | |

| 53 | |

| 54 | |

| 55 | al-Kāshānī and Hamza (2021), A Sufi Commentary, p. 303. For the Arabic original, refer to: ʿAbd al-Razzāq al-Kāshānī, Taʾwīlāt Al-Qurʿān, published as Tafsir Ibn ʿArabī. Beirut: Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya, n.d. |

| 56 | |

| 57 | Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 1/191; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020a), The Openings Books 1 & 2, p. 187. |

| 58 | |

| 59 | |

| 60 | |

| 61 | This translation, for the most part, is based on Ibn ʻArabī et al. ([2000] 2008), The Seven Days, p. 34, except for a small variation in wording in the rāʾ prayer in the Tawajjuhāt al-ḥurūf, pp. 25–26. |

| 62 | Quran 21:90. |

| 63 | We suggest a variant reading, ‘freeing of necks’, as discussed in the subsequent section. |

| 64 | Quran 40:7. |

| 65 | Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 1/244; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020a), The Openings Books 1 & 2, p. 281. |

| 66 | |

| 67 | see note 66. |

| 68 | Chittick (1993), “Two Chapters”, p. 105. Ibn ʿArabī frequently made references to Quranic verse 28:88, which states, “All things perish, except His Face.” According to Chittick, Ibn ʿArabī presents two ways to understand this verse. In the first instance, it is read as referring to the face of God in the thing, and in the second instance to the face of the thing in God. Despite the apparent differences, these interpretations ultimately converge, highlighting the same face identical to the intrinsic reality or immutable entity of the thing. Ibn ʿArabī employs the term ‘specific face’ (al-wajh al-khāss) to elucidate this concept, which refers to the unique face of God exclusively turned towards each individual existent, endowing it with its own uniqueness (Chittick, p. 120 note 52). |

| 69 | Quran 2:115. |

| 70 | Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 1/228; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020a), The Openings Books 1 & 2, p. 251. |

| 71 | |

| 72 | See Ibn ʿArabī and Jaffray (2015), The Secrets of Voyaging, pp. 65–66. Ibn ʿArabī refers to Q. 17:1, ‘Glory be to Him, who carried His servant (bi-abdihi) by night from the holy mosque to the further mosque.’ Specifically, he refers to the Prophet Muhammad’s prostration in the two mosques (sing. masjid, having the same root as sujūd). This is the essence of servitude, which is ‘lowness’ (dhilla) and ‘lowering’ (khafḍ). Noting that khafḍ is also a grammatical lowering for pronouncing the final consonant of a genitive case with /i/. |

| 73 | |

| 74 | |

| 75 | |

| 76 | |

| 77 | see note 76. |

| 78 | E.g., ch. 24, titled ‘On the hearts who are impassioned by the breaths’ in Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020b), The Openings Books 3 & 4, p. 113; Al-Manṣūb, al-Futūḥāt, 1/546. And ch. 49 entitled, “On Maʿrifah of His (peace be upon him) word, “I indeed have found a breath of the al-Raḥmān from the side of Yemen,” in Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020b), The Openings Books 3 & 4, p. 469; Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 2/72. |

| 79 | In Arabic grammar, khafḍ is a term that refers to the grammatical concept of ‘lowering,’ which manifests itself through the shifting of vowel placement, specifically from fatḥa /a/ or ḍamma /u/ to kasra /i/, resulting in a lower sound. |

| 80 | The poem is recited by a friend of Ibn ʿArabī who lived in Damascus, Yaḥyā bin al-Akhfash, in Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 2/73; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020b), The Openings Books 3 & 4, p. 472. |

| 81 | Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 2/74; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020b), The Openings Books 3 & 4, pp. 474–75. The poetic form of qaṣīda opens with a brief elegiac mood (nasib), followed by a recounting (rahil) of the poet’s personal life and his people, the Anṣār (lit. ‘the helpers’ or those who bring victory’) who took prophet Muhammad and his followers into their homes when they fled prosecution from Mecca, and finally the main theme (madih) in which he pays tributes to himself, his community and his Prophet. |

| 82 | See discussion on the words raddada and radda that share the root r-d-d. |

| 83 | Takrār: besides the idea of recurrence and return, it also means purifying and clarifying. |

| 84 | Sahih Muslim 2655, Book 46, Ḥadīth 29. In examining the significance of the terms ‘face’, ‘fingers’, ‘hands’ of God, it is important to note the historical polemics within Islamic theology (kalām) surrounding tanzīh (God’s incomparability or transcendence) and tashbīh (God’s similarity and anthropomorphism). Different theological movements and schools have accused one another of emphasizing either transcendence or anthropomorphism. Regarding the problem of the anthropomorphism of language, Lory remarks that, ‘Ibn ‘Arabī does not allow himself to be confined by such objections. For him, language is not unequivocal and its use is not limited by the rules of syntax or to dictionary meanings. Rather, it has a vertical dimension that goes right back to the origin of things...to convey the experience of the divine through paradox without destroying the proper coherence of the language,’ [n.p]. Ibn ʿArabī adopts these two terms from kalām, but he insists on affirming both God’s similarity to and difference from our perceptible world. Despite their apparent contradiction, he asserts that the Quran effectively conveys the truth of God’s simultaneous transcendence and immanence. This truth is exemplified by the Quranic names of God, particularly al-Bāṭin (the Hidden) and al-Ẓāhir (the Apparent), which encompass both the inward and outward aspects, the manifest and unmanifest. According to Ibn ʿArabī, human beings derive their reality from the ultimate reality of God. While the divine attributes may appear anthropomorphic from our limited human perspective, they are, in fact, theomorphic. This signifies that human attributes reflect the nature of God, rather than the other way around, as the creatures were created in God’s form. He employs the metaphor of the polished mirror to illustrate the idea of mirroring between the image of God (His) and the image of the servant (his). The polished mirror symbolizes the mystical union and is constituted within the heart of the ‘complete human’ insān al-kāmil). For discussions on anthropomorphism in Ibn ʿArabī’s works see e.g., Chittick (1989), The Sufi Path; Chittick, The Self-Disclosure of God, Albany: SUNY, 1998. P. Lory, “The Symbolism of Letters and Language in the Work of Ibn ʿArabī,” JMIAS XXIII, 1998 [n.p], https://ibnarabisociety.org/symbolism-of-letters-and-language-pierre-lory/ (accessed on 12 May 2023); T. Izutsu, Sufism and Taoism, Univ. of California Press: Berkeley, 1983; M A. Sells, Mystical Languages of Unsaying. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994. |

| 85 | |

| 86 | |

| 87 | The single instance that it specifically means “neck” is in the verse Quran 47:4. |

| 88 | Quran 38:75. |

| 89 | Ibn Rushd asked young Ibn al-ʿArabī, ‘How did you find the situation in unveiling and divine effusion? Is it what rational consideration gives to us.’ Ibn al-ʿArabī replied, ‘Yes and no. Between the yes and the no spirits fly from their matter and heads from their bodies,’ in Chittick (1989), The Sufi Path, xiii. |

| 90 | Chodkiewicz (2015), “The Paradox of the Kaʿba”, n.p. |

| 91 | |

| 92 | |

| 93 | |

| 94 | Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 1/545; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020b), The Openings Book 3 & 4, p. 111. |

| 95 | Compared to the poem in chapter 330 of the Futūḥāt with the consonant rāʾ as rawī. |

| 96 | |

| 97 | |

| 98 | Warīd (jugular vein) draws our attention to God’s sheer intimacy with each creature. |

| 99 | We are grateful to Mostafa Zekri for bringing this crucial information to our attention. |

| 100 | Ibn ʿArabī and al-Manṣūb (2010), al-Futūḥāt, 1/227; Ibn ʻArabī and Winkel (2020a), The Openings Books 1 & 2, pp. 248–59. |

| 101 | |

| 102 |

References

- al-Kāshānī, ʿAbd al-Razzāq, and Feras Hamza. 2021. A Sufi Commentary on the Qurʾān: Taʾwīlāt Al-Qurʾān Volume 1. Cambridge: The Royal Aal al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought and The Islamic Texts Society. [Google Scholar]

- al-Naṣṣir, Abdulmunʿim Abdulamīr. 1993. Sibawayh the Phonologist: A Critical Study of the Phonetic and Phonological Theory of Sibawayh as Presented in His Treatise Al-Kitab. London: Kegan Paul International. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, Amatullah. 2001. Sufi Terminology (Al-Qamus Al-Sufi): The Mystical Language of Islam. Lahore: Ferozsons. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiar, Laleh. 2011. Concordance of the Sublime Qurʾān. Chicago: Library of Islam and Kazi Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Beneito, Pablo, and Stephen Hirtenstein. 2021. Patterns of Contemplation: Ibn ʿArabi, Abdullah Bosnevi and the Blessing-Prayer of Effusion. Oxford: Anqa Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Chittick, William C. 1989. The Sufi Path of Knowledge: Ibn Al-ʻArabi’s Metaphysics of Imagination. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chittick, William C. 1993. Two Chapters from the Futūḥāt al-Makkīyah. In Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabi: A Commemorative Volume. Edited by Stephen Hirtenstein and Michael Tiernan. Shaftesbury: Element for the Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabi Society, pp. 90–123. [Google Scholar]

- Chodkiewicz, Michel. 1993. An Ocean Without Shore: Ibn ʻArabī, the Book, and the Law. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chodkiewicz, Michel. 2015. The Paradox of the Kaʿba. Journal of the Muhyiddin Ibn Arabi Society 57. Available online: https://ibnarabisociety.org/the-paradox-of-the-kaaba-michel-chodkiewicz (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Gril, Denis. 2004. The Science of Letters. In The Meccan Revelations: Ibn ʻArabī. Edited by Michel Chodkiewicz, Cyrille Chodkiewicz and Denis Gril. New York: Pir Press, vol. II, pp. 105–219. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn ʻArabī, Muhyiddin, Pablo Beneito, and Stephen Hirtenstein. 2008. The Seven Days of the Heart: Awrād al-Usbūʻ (Wird) Prayers for the Nights and Days of the Week. Oxford: Anqa Publishing. First Published 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn ʻArabī, Muhyiddin, Pablo Beneito, and Stephen Hirtenstein. 2021. Prayers for the Week: The Seven Days of the Heart (Awrād al-Usbūʻ). Critical Edition. Oxford: Anqa Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn ʿArabī, Muhyiddin, and ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz Sulṭān al-Manṣūb. 2010. Al-Futūḥāt al-Makkīyah. Critical Edition 12 vols. Cairo: Majlis al-aʿala lil-thaqāfah, All subsequent citations refer to this edition. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn ʿArabī, Muhyiddin, and Angela Jaffray. 2015. The Secrets of Voyaging (Kitāb al-Isfār ‘an Natāʾij al-Asfār). Oxford: Anqa Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn ʿArabī, Muhyiddin, and Eric Winkel. 2020a. The Openings Revealed in Makkah: Books 1 & 2 (al-Futūḥāt al-Makkīyah). New York: Pir Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn ʻArabī, Muhyiddin, and Eric Winkel. 2020b. The Openings Revealed in Makkah Books 3 & 4 (al-Futūḥāt al-Makkīyah). New York: Pir Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn ʻArabī, Muhyiddin. n.d. Tawajjuhāt al-ḥurūf. Cairo: Maktabat al-Qāhira.

- McAuliffe, Jane Dammen. 2001. Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān: Volume One A–D. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, James Winston. 2007. The Reflective Heart: Discovering Spiritual Intelligence in Ibn Arabi’s Meccan Illuminations. Lahore: Suhail Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Rašić, Dunja. 2021. The Written World of God: The Cosmic Script and the Art of Ibn ʿArabī. Oxford: Anqa Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rašić, Dunja. 2022. Celestial Mechanics: Letters, Elements and Prime Matter in Ibn ʿArabī’s Mystical Cosmogony. Journal of the Muhyiddin Ibn Arabi Society 72: 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Salvaggio, Federico. 2021. Polysemy as Hermeneutic Key in Ibn ʿArabī’s Fuṣūṣ al-Ḥikam. Annali di Ca’ Foscari. Serie Orientale 57: 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ق qāf | خ khāʾ | غ ghayn | ح ḥāʾ | ع ʿayn | ه hāʾ | ا alif |

| ر rāʾ | ل lām | ي yāʾ | ش shīn | ج jīm | ض ḍād | ك kāf |

| س sīn | ز zāy | ص ṣād | ت tāʾ | د dāl | ط ṭāʾ | ن nūn |

| و wāw | م mīm | ب bāʾ | ف fāʾ | ث thāʾ | ذ dhāl | ظ ẓāʾ |

| لا lām-alif |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramlan, K.; Ludovico, A. Desiring the Sweet Perfume of Closeness in the Oscillating Tawajjuh of the Letter Rāʾ. Religions 2023, 14, 692. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060692

Ramlan K, Ludovico A. Desiring the Sweet Perfume of Closeness in the Oscillating Tawajjuh of the Letter Rāʾ. Religions. 2023; 14(6):692. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060692

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamlan, Kris, and Ana Ludovico. 2023. "Desiring the Sweet Perfume of Closeness in the Oscillating Tawajjuh of the Letter Rāʾ" Religions 14, no. 6: 692. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060692

APA StyleRamlan, K., & Ludovico, A. (2023). Desiring the Sweet Perfume of Closeness in the Oscillating Tawajjuh of the Letter Rāʾ. Religions, 14(6), 692. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060692