Chinese Wu, Ritualists and Shamans: An Ethnological Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction: What Is the Wu?

2. Cross-Cultural Methods: A Derived Etic Model of Religious Practitioners

2.1. Social Predictors of Ritualist Types

- Shamans (Foraging Shamans), the only ritualists in societies with a principal reliance on foraging and without intensive agriculture, supra-community political integration or warfare;

- Shaman/Healers (Agricultural Shamans) found in societies with intensive agriculture but lacking supra-community political integration, and generally with the presence of another ritualist, the Priests;

- Priests are found in intensive agricultural societies with supra-community political integration and are always found in societies with the following types of ritualists:

- Healers, who are generally found in agricultural societies, but significantly predicted by supra-community political integration and the practice of warfare for resources;

- Mediums, characteristic of complex societies and significantly predicted by supra-community political integration and the presence of warfare for captives; and

- Sorcerer/Witches in societies with intensive agriculture and supra-community political integration, but lack community integration (see Winkelman 2022 for analyses).

2.2. Cross-Cultural Features of Foraging Shamans (SCCS Variable 879)

- Pre-eminent group leader who performs a dramatic night-time communal ritual involving enactments, drumming, dancing and singing;

- Principal ritual functions of spirit communication for healing, divination, hunting and sorcery;

- Selection for the role through spirit encounters interpreted as an illness and experienced in visions and dreams;

- Training with vision quests in the wilderness with fasting, austerities and often psychoactive plants;

- An initiatory experience of death by animals which killed and dismembered the initiate, followed by a rebirth and a reconstruction by animals incorporated as a principal power;

- Ritual preparations of fasting and sexual abstinence;

- Altered states of consciousness (ASC) conceptualized as magical or soul flight (out-of-body experience) and an experience of personal transformation into an animal, but notably the absence of possession in the ASCs;

- Healing practices focused on recovery of patient’s lost soul, combating evil spirits and the extraction of magical darts causing illness;

- Causing illness and death through darts, sorcery and soul theft; and

- Directing hunters and calling animals.

2.3. Biogenetic Bases of Shamanism

- A collective night-time/overnight conspicuous display with community drumming, dancing and singing which have deep evolutionary antecedents illustrated in the homologous sociality-enhancing maximal displays of chimpanzees (Winkelman 2009, 2021b);

- Selection for the shamanic role based on spontaneous visions, dreams and sickness involving natural tendencies for ASC that enhance access to and integration of unconscious processes (Winkelman 2010a, 2011, 2021c);

- Training in the alteration of consciousness (i.e., ASC) induced by practices of isolation in the wilderness, fasting, abstinence and austerities that stimulate the neuromodulatory neurotransmitter systems (Winkelman 2017);

- ASC induced by engaging the mimetic operator (dancing, singing, drumming) which produce an activation of the endogenous opioid system (Winkelman 2017, 2021a);

- Ritual activities leading to exhaustion and collapse, producing experiences of communication with spirits and out-of-body experiences reflecting innate modules (Winkelman 2015, 2021c);

- Initiatory experiences of death/dismemberment from attacks by animals and a rebirth that produces experiences of personal transformation and of incorporating animal powers into identity and basic structures of self-consciousness (Winkelman 2010a);

- Spiritual experiences produced by stimulation, integration and dissociation of innate modular cognitive structures operators (Winkelman 2021d); and

- Healing by recovery of lost soul, extraction of objects and removal of sorcery by ritual elicitation of endogenous healing mechanisms (Winkelman 2010a)

- Mimetic community ritual: mimetic enactments in dramatic performances, collective drumming, dancing and singing;

- Traumatic selection: a psychological dynamic manifested in spontaneous visions, special dreams and psychosis-like sickness;

- ASC: out-of-body (soul flight) experiences and initiatory experiences of death and dismemberment by animals followed by rebirth;

- Animal powers: Central roles of animals in formation of personal powers and experiences of personal transformation into animals;

- Healing: involving recovery of soul loss or theft, extraction of sorcery objects and removal of effects of attacking spirits

3. Comparative Analyses: Different Types of Wu in Cross-Cultural Perspective

- (1)

- Pre-historic Neolithic wu revealed in archaeological (Tong 2002) and linguistic (Hopkins 1945) evidence;

- (2)

- Ancient wu (focused on the men wy xi, rather than women wu) from the Shang and Zhou periods;

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

- (6)

- (7)

- (8)

- the bo of the Tu ethnic group of Qinghai Province in Northwest China, who is called a shaman by Xing and Murray (2018).

3.1. Pre-Historical Wu

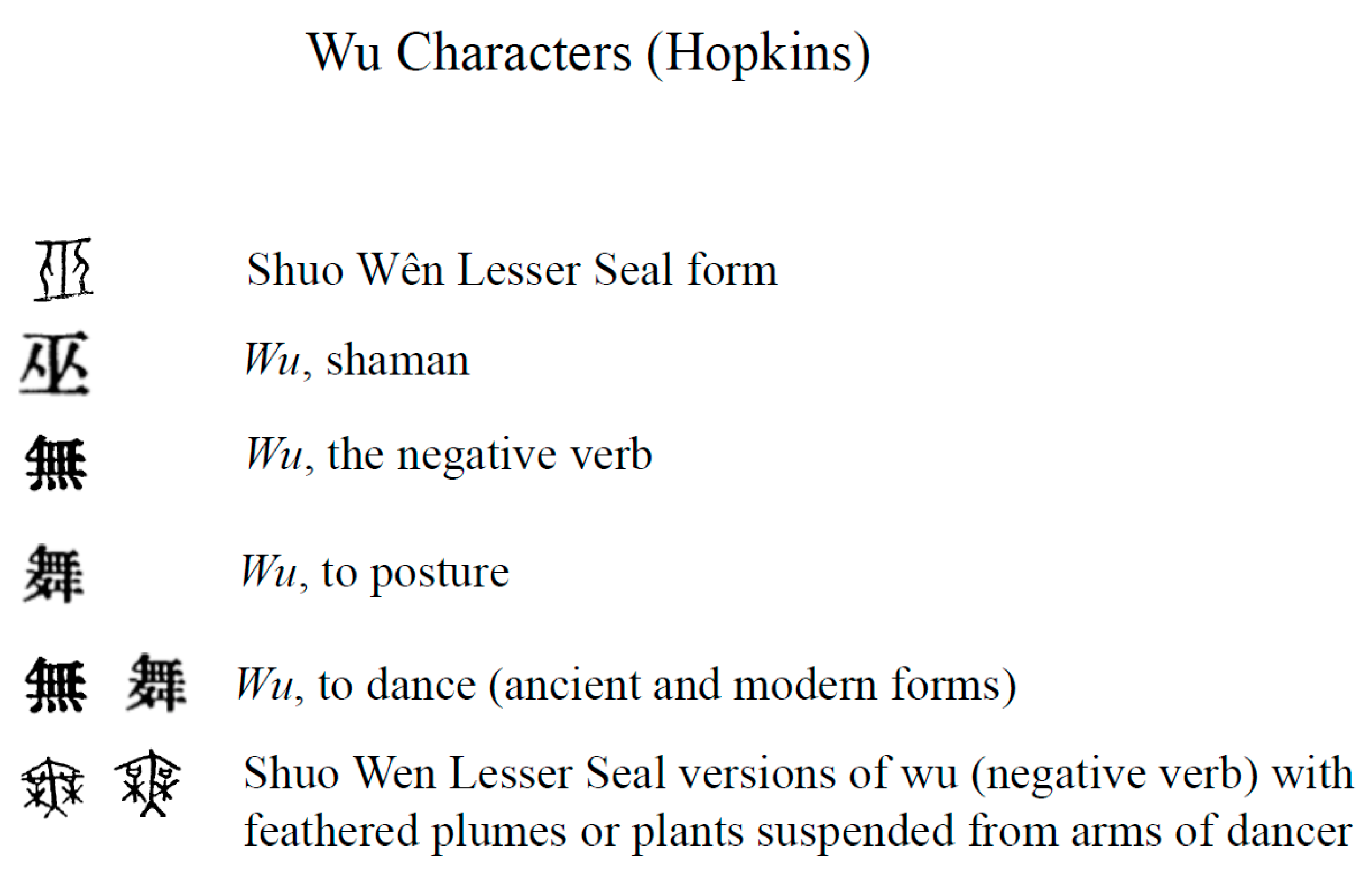

), concluding that ku wén and wu represent the same sound and word. Furthermore, they resemble representations depicted in “early Bronzes and the inscribed Bones of the Honan Find”. Hopkins suggests these Lesser Seal sources present a recognizable portrait of a dancing or posturing figure, a direct mimetic representation using straight and curving lines to symbolically represent an unmistakable dancing figure (see Figure 2). These dancing activities have a direct affinity to the core biogenetic mimetic bases of the practices of shamans.

), concluding that ku wén and wu represent the same sound and word. Furthermore, they resemble representations depicted in “early Bronzes and the inscribed Bones of the Honan Find”. Hopkins suggests these Lesser Seal sources present a recognizable portrait of a dancing or posturing figure, a direct mimetic representation using straight and curving lines to symbolically represent an unmistakable dancing figure (see Figure 2). These dancing activities have a direct affinity to the core biogenetic mimetic bases of the practices of shamans.

; Lesser Seal form

; Lesser Seal form  ), referring to two hands, but rather the character ch’uan (

), referring to two hands, but rather the character ch’uan ( ), referring to two feet (p. 4). Either interpretation confirms the mimetic base in the clapping or dancing figure of the shaman, activities that can induce ASC and are a core feature of shamanism. Hopkins reviews evidence showing that the meanings of the character wu are in agreement with the notion of dancing represented in ts’ung wu chih i, (

), referring to two feet (p. 4). Either interpretation confirms the mimetic base in the clapping or dancing figure of the shaman, activities that can induce ASC and are a core feature of shamanism. Hopkins reviews evidence showing that the meanings of the character wu are in agreement with the notion of dancing represented in ts’ung wu chih i, ( ) referring to the ritual dancing of the typical yü (

) referring to the ritual dancing of the typical yü ( ) ceremony customary in the Yin Dynasty.

) ceremony customary in the Yin Dynasty. or wu tung

or wu tung  ) graphically as meaning “to dance” but functionally, its representation as wu has the meaning of “the negative verb”. Hopkins proposes that a disentanglement of the three modern characters that are pronounced as wu can be achieved by reference to their primitive contours that reveal their pristine meanings. Hopkins proposes the three modern characters represented in English as wu have interrelated meanings of “shaman”, “the negative verb” and “to posture,” and that “all be traced back to one primitive figure of a man displaying by the gestures of his arms and legs the thaumaturgic powers of his inspired personality” (p. 4).

) graphically as meaning “to dance” but functionally, its representation as wu has the meaning of “the negative verb”. Hopkins proposes that a disentanglement of the three modern characters that are pronounced as wu can be achieved by reference to their primitive contours that reveal their pristine meanings. Hopkins proposes the three modern characters represented in English as wu have interrelated meanings of “shaman”, “the negative verb” and “to posture,” and that “all be traced back to one primitive figure of a man displaying by the gestures of his arms and legs the thaumaturgic powers of his inspired personality” (p. 4).| Chinese Character | Pinyin | English |

|---|---|---|

| 巫 | Wu | |

| 巫 祝也 | Wu zhu ye | Invoker, imprecator (Hopkins 1945); Sorcerer (Shuowen Jiezi 2014) |

| 覡 | Wu Xi | Male Shamans (Cai 2014); Male Sorcerer (Xu 2002) |

| 巫醫 | Wu Yi | Physicians who treat medical and surgical conditions (Lin 2009) |

| 民巫 | Min Wu | Commoner Wu (Lin 2009, 2016) |

| 官巫 | Guan Wu | Generic term for officially appointed Wu (Lin 2016) |

| Female Wu | ||

| 巫尪 | Wu Wang | Female witch (Du and Kong 2000) |

| 巫嫗 | Wu Yu | Female witch/sorcerer (Takigawa 2015) |

| 巫蛊 | Wu Gu | Witchcraft activities (Lin 2009; Cai 2014) |

3.2. Ancient Wu Xi

| Ritualist Type | Principal Magico-Religious Activity | Selection and Training | Social and Political Power | Professional Characteristics | Motive and Context of Ritual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaman (Forager Shaman = S; (AS for added Agriculture Shaman feature) | Healing and divination Protection from spirits and malevolent magic. Hunting magic (S) Cause illness, death (S, S/W) Assist Priests in agricultural rituals (AS) | Dreams, illness, and signs of spirit’s request (S) Vision quest by individual alone in wilderness (S) Group training (AS). Ceremony recognizes status (AS) | High social status. Charismatic (S) Communal and war leader (S) Makes sorcery accusations. Informal power Moderate judiciary decisions (AS) | Predominantly male, female secondary (S) Part time. Individual practice (FS) Group ceremonies (AS) Specialized role (AS) Ambiguous moral status (S) | Acts at client request in community-wide ceremony Ceremony over- night (S) Performance in client group at client request (AS) |

| Xi-“Ancient Shamans” (Shang and Zhou periods | Healing & divining Divine people’s fate, regarding illness Sacrifices for deceased, spirits and gods (M, H) Ancestor worship (P) Harvest, livestock (H, P) | Hereditary aristocrats (P) | Ruling class (H, P) Religious affairs of state (H, P) Very important and great influence | Males (H, P) Correct demeanor, the value of loyalty and trustworthiness People of superior quality, with high intelligence and respected (*S) | Religious functions of government (H, P) |

| Commoner Domestic Professional wu Shang and Zhou periods | Healing and protection Arts of divination Determine causes of misfortune Rituals to harm people and gain advantage (S) Worship ghosts, animals and natural phenomena | Hereditary family trade Innate selection or from disease (S, M) No formal group (S) | Commoner class (M) Familial/tribal function (S) Prestige but little power (S, M) Influence communal decisions, warfare and hunting (S) May be sanctioned, executed (SW) | Male and Female (S) Made a living but part-time (S, M) Often defective in body or handicapped (S*) Both heal and harm (ambiguous moral status) (S) | Services for clients Covet goods and heat people Profession for gain (H) |

| Healer (H) Etic Ritualist Type | Healing and divination. Agricultural and socioeconomic rites (H, P) Propitiation (H, P) Life-cycle rituals. | Voluntary selection, large payments to trainer. Learn rituals and techniques Ceremony recognizes status. | High socioeconomic status. Judicial, legislative, and economic power (H, P) Denounce sorcerers. | Predominantly male (H, P) Full-time (H, P) Collective training, practice and ceremony. Highly specialized role Predominantly moral | Acts at client request and treatment in client group. Collective public rituals with Priests |

| Chinese Reindeer-Evenki šaman | Treatment of illnesses Ward off misfortune Seasonal celebrations Life-cycle (marriage, funerals and memorials) Divining and predicting Malevolence (S, S/W) | Dreams and visions Illness/hysteria (S, M) Could be inherited Solitude and fasting in wilderness (S) Self/Spirit taught (S) Death-and-rebirth (S) | Great significance for community = charismatic (S) Unofficial leader (S) Not official clan head or political leader No material advantage | Male & female (S) Part-time More mentally capable(S) Courageous & strong Ambiguous morality—required altruism but might abuse power (S) | Altruism for benefit of community (S) Acted when person or community was disturbed Community obliged the ritualist to perform (S) |

| Ritualist Type | Supernatural Power/Ritual Techniques | ASC Conditions | ASC Characteristics and Techniques | Healing Concepts and Practices | |

| Shaman (Forager Shaman = S) (AS Additional Agriculture Shaman features) | Animal spirits & allies (S) Spirit power usually controlled (S) Impersonal mana (AS) Spells, charms, exuvial and imitative techniques (AS). | ASC in training and practice. Soul flight/journey (S) Death-and rebirth (S) Animal transform (S) Mystical ASC (AS) | Isolation, austerities, fasting, chanting, singing, drumming and dancing. Collapse during ritual Unconsciousness (S) | Soul loss (S) Spirit aggression, sorcery. Sucking, blowing, massaging and object extraction (S) Plant medicines. Incantations for removal | |

| Xi-“Ancient Shamans” (Shang and Zhou period) | Animals (S?) Sacrifices (H, P) Pray for blessing (H, P) Use statues and icons (H) Incantations Bone Oracles (H) | Knew how to ascend and descend (S?) Vision illuminated matters and hearing penetrated them (S?) | Bathe and fast Beat drum, strike bell and holler Excite the heart, body Music, dancing, and drumming | Knowledge of plants Removal of illness Exorcism (H) Pray to gods for blessing to averting misfortune (H, P) Dream interpretation | |

| Commoner Domestic Professional wu Shang and Zhou Periods | Spirits and ghosts of dead, not “orthodox gods” Incantations, blessings, praying (H) Curses, charms (AS) Sacrifice (H, P) Animals (?) (S) | Communicate with spirits Imaginary travel around heaven & earth (S) | Drumming and music performed by practitioners Purgative drugs (S*) | Expelling baleful influences, Exorcism (H, M) Pray to invoke the ghosts and gods for blessings (H, P) Sacrifice (H, P) | |

| Healer Etic Ritualist Type | Superior gods and impersonal power (mana). Charms, spells, rituals, formulas and sacrifice. Propitiate & command spirits. Material divination system | ASC induction limited No apparent ASC (H, P) | Social isolation; fasting; minor austerities; limited singing, chanting or drumming. | Exorcism and prevent illness. Manipulate body Empirical medicine Imitative and exuvial techniques. | |

| Chinese Reindeer-Evenki šaman | Supernatural qualities of animals (S) Changed themselves into animals (S*+) Master of the spirits who were subservient (S) | Techniques of ecstasy Soul travel to spirit world (S) Death-and-rebirth (S) Change into animal (S) | Drumming and singing central elements for trance Unconscious trance (S) May use alcohol (P*) | Soul loss/recovery (S) Remove malevolent influences of spirits Drum and singing had hypnotic influence on patient Medicinal herbs and plants |

3.2.1. Comparisons of Ancient Wu Xi and Shamans (SCCS Variable 879)

3.2.2. Comparisons of the Ancient Xi Wu with the Healer (SCCS Variable 881)

3.3. Commoner Wu

Comparing the Commoner Wu and Shamans (SCCS Variable 879)

3.4. Bureaucratic Wu Priests

| Chinese Character | Pinyin | English Terms Used by von Falkenhausen (1995) and Lin (2009) |

|---|---|---|

| 男巫 | nanwu | Male shamans |

| 女巫 | nüwu | Female shamans |

| 司巫 | siwu | Manager of the Spirit Mediums |

| 師巫 | shiwu | Officers |

| 巫師 | wushi | Instructors of Spirit Mediums |

| 巫恆 | wuheng | Spirit Mediums |

| 無數 | wushu | Male and Female Spirit Mediums |

| 宗 | zong | Temple Official |

| 祝 | zhu | Invocators |

| 大祝 | dazhu | Great Invocator |

| Ritualist Type | Principal Magico-Religious Activity | Selection and Training | Social and Political Power | Professional Characteristics | Motive and Context of Ritual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Priest (P) Etic Ritualist Type | Propitiation and worship. Protection and purification. Agricultural planting and harvest rites. Socioeconomic rites. | Social inheritance or succession. Political action. Incidental training and/or by group. Ceremony recognizes status. | High social and economic status. Political, legislative, judicial, economic, and military power. Exclusively moral. | Exclusively male. Full-time. Hierarchically organized practitioner group. High social and economic status. | Acts to fulfill social functions, calendrical rites. Public rituals. |

| Official wu (siwu, nanwu, nüwu)—Zhou dynasty | Sacrifices to gods in ancestral temple (P) Protect from disaster (P) Rituals for rain-making, driving away pestilence, protect harvest (H, P) Funerary services (H) | Selected/appointed by government personnel (P) State officials in charge of training (H, P) | Part of official structure and ruling circles (H, P) Regular members of the bureaucracy (H, P) Political and economic activity (H, P) | Male , full-time (P, H) Specialized hierarchy (H, P) Skills and knowledge from study High prestige from their positions (H, P) | Social functions-Formal rituals at temples (P) Calendrical rituals at temples at specified times (P) |

| Bo of the Tu (Xing and Murray) | Ensure good weather and agriculture (P, H) Ancestors worship (P) Life cycle events Community well-being Resolve conflicts Not a source of healing | Hereditary, passed down from one generation to the next within the same family (P) | Leadership in collective rituals (P) Intervene to resolve conflicts (P) | Only males (P, H) Part-time specialist | Annual festival (P) Organized by village association Public festival in temple (P) Entire community participates (S) |

| Medium (M) Etic Ritualist Type) | Healing and divination. Protection from spirits and malevolent magic. Agricultural rituals. Propitiation. | Spontaneous possession by spirit. Training in practitioner group. Ceremony recognizes status. | Low socioeconomic status. Informal political power. May designate who are sorcerers and witches. Exclusively moral. | Predominantly female; male secondary/rare. Part-time. Collective group practice. | Acts primarily for clients at client residence. Also participates in public ceremonies |

| Female Wu—Qin and Han dynasties, especially Warring States | Communicate with gods Assure well-being of king and state Control rains for agriculture (P, M) Healing rituals Funeral rites | Appointed to positions in the royal courts Group training (M) Male spirit or god descends on person (M) | Generally low status (M) Contributed to bureaucratic and political decisions with divination (H, P) | Female (M) Organization served the royal court (M) | Assure well-being of king and state (P) Regular times throughout year (P) |

| Sorcerer/ Witch (SW) Etic Ritualist Type) | Malevolent acts. Kill friends, enemies, neighbors, even kin. Cause illness, death, and economic destruction. | Social labeling/accusation. Attribution of biological inheritance. Innate abilities, self-taught or learned. | Low social and economic status. Exclusively immoral. May be killed. | Male and female. Part-time. Little or no professional organization. | Acts at client’s request or for personal reasons such as envy, anger, jealousy, greed or revenge. Practices in secrecy. |

| Wugu | Cause illness and death (S, SW) | Denounced by government officials (SW) | None May be killed, executed (SW) Condemned as immoral (SW) | Males and females (S, SW) Lower class (SW) | Personal gain, payment (SW) Revenge (SW) |

| Ritualist Type | Supernatural Power/Control of Power | ASC Conditions | ASC Techniques and Characteristics | Healing Concepts and Practices | |

| Priest (P) (Etic Ritualist Type) | Power from ancestors, superior spirits or gods. Impersonal power and ritual knowledge. Propitiation and sacrifices. No control over spirits. | Generally no ASC or very limited | Occasionally alcohol (P) Sexual abstinence, isolation, sleep deprivation. | Purification and protection. Public rituals and sacrifices. | |

| Official wu (siwu, nanwu, nüwu)—Zhou dynasty (1046-256 BC) | Relate to royal ancestors, high gods (H, P) Knowledge of texts and rituals (H, P) Appease ancestors (P) | Not reported/apparent (P, H) | Music, dancing, and drumming | Exorcisms (M, H) Sacrifices (M, H, P) Protection (P) Prayer (H) * | |

| Bo of the Tu (Xing and Murray) | Protective, ancestor and tutelary spirits of village (P) Spirits not controlled-- may refuse to help (P, H, M) Procedures in hopes of coercing spirits Knowledge & skills | Possessed by spirits (M?) Become different spirits Spirits answer through mouth of bo (M) | Shivering with presence of a spirit (M?) Uses a drum and special chants and dances | Not source of help in illness (P) | |

| Medium (M) (Etic Ritualist Type) | Possessing spirits dominate. Propitiation and sacrifices. Power dominates Unconscious. | ASC in training and practice. Possession ASC | ASC induced through singing, drumming, and dancing. Tremors, convulsions, seizures, compulsive behavior, amnesia, dissociation. | Possession and exorcisms. Control of possessing spirits. | |

| Female Wu- Warring States period | Appealed to deities with sacrifices & prayers (P, M) Decision maker the possessing male spirit (M) Spirit or god descends on person (M) | Gods merged with personality of wu (M) Possessing male spirit or god descends on person (M) | Induction with dancing, incantations, singing and wailing | Spirit responsible for disease Perform exorcisms (M, H) Herbal healing Sacrifices, prayers, spells, incantations Anointing and ablutions | |

| Sorcerer/ Witch (SW) (Winkelman Etic Ritualist Type) | Power from spirits and ritual knowledge. Contagious, exuvial and imitative magic, spells. Power can be unconscious, out of control. | Indirect evidence of ASC in reported flight and animal. transformation. | Night-time activities. | Illness by consuming victim’s soul, spirit Aggression, magical darts that enter victim Unconscious emotional effects of envy, anger, etc. | |

| Wugu | Incantations and Poisons Imitative magic (S, S/W) Cursing (SW) Burial of puppets | Nighttime activities (S, SW) | Ambition, greed (S/W) |

Comparing Bureaucratic Wu and Priests (SCCS Variable 884)

- primary religious activities (ancestor worship, agricultural well-being);

- selection (for the highest level, social succession/inheritance and political action);

- socio-political power (highest political, economic and judicial power);

- professional characteristics (male, full-time, specialized hierarchy, high status);

- motive and context of ritual (social functions, public calendrical rituals);

- supernatural power (ancestors, superior gods, ritual knowledge);

- ASC (very limited); and

- Healing (sacrifices).

3.5. Female Wu

Comparing Female Wu with Mediums (SCCS Variable 882) and Shamans (SCCS Variable 879)

3.6. Wugu as Malevolent Wu

Wugu as a Sorcerer/Witch (SCCS Variable 883)

3.7. The Chinese Reindeer-Evenki Shaman

Comparisons of Šaman with Foraging Shamans (SCCS Variable 879)

3.8. Is the Contemporary Chinese Tu Bo a Shaman?

4. Results: A Summary of Shared Features and Divergences

- Ritual: (two variables) Community-wide ritual held over-night

- Distinctive Functions: (two variables) Malevolence/Sorcery, warfare

- Selection & training: (four variables) Dreams and illness as signs of spirit’s request, vision quest alone in the wilderness, death-and-rebirth experience, self/spirit taught

- Social Characteristics: (three variables) Charismatic leader, informal power, male and female

- ASC: (two variables) Unconscious period, out-of-body (soul flight),

- Animal powers: (three variables) Animals as a personal and supernatural power, experiences of animal transformation, hunting magic

- Healing: (three variables) Soul loss and recovery, sucking/object extraction, the expulsion of attacking spirits (vs exorcism of possession).

- Ancient wu xi or wu yi: Healer

- Commoner wu: Agricultural Shaman

- State religious officials, bureaucratic wu: Priest

- Female wu of the Warring States period: Medium

- Guwu of the Han period: Sorcerer/Witch

- Chinese Reindeer-Evenki šaman: Foraging Shaman

- Bo of the Tu ethnic group of Qinghai Province: Priest

5. Discussion: Critical Assessment of Translating Wu as Shaman?

So What Is a Shaman?

6. Conclusions: The Wu Is a Religious Ritualist, Not a Shaman

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For updated variables, values, variable descriptions, coding instructions and data see Winkelman and White (1987) or the Mendeley data repository at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/34pjbr4kg4/2. |

| 2 | This access was made available by Doug White (RIP) but no longer appears available to the public. |

| 3 | Also referred to here as a Foraging Shaman. |

| 4 | Also referred to here as an Agricultural Shaman. |

| 5 | Winkelman (1992, p. 29) reports that the variables were attributed to a type if it was reported for 67% of the practitioners of the type or if the incidence of the variable for the practitioner type was at least 50% of all cases reported for the variable. In the case of Shamans, all cases of variables of less than 100% were correlated with data quality sources, with the consistently positive correlations indicating missing data (under reporting) rather than true absence. |

| 6 | Analyses were performed in the CosSci program housed at the University of California, Irvine at http://socscicompute.ss.uci.edu/. This system is no longer publicly available. |

| 7 | I have not provided a comparison with the Pre-historic Neolithic wu because of the lack of adequate data for a meaningful assessment. |

| 8 | Table 5 shows more than six matches with Mediums, but they are overlapping features. |

References

- Allan, Sarah. 2015. When Red Pigeons Gathered on Tang’s House: A Warring States Period Tale of Shamanic Possession and Building Construction set at the turn of the Xia and Shang Dynasties. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 25: 419–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boileau, Gilles. 2002. Wu and Shaman. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 65: 350–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cai, Liang. 2014. Witchcraft and the Rise of the First Confucian Empire. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Yu, and Yingda Kong. 2000. Chunqiu Zuozhuan Zhengyi [A Commentary on Chunqiu Zuozhuan]. In Shisan Jing Zhushu [A Commentary on the Thirteen Classic Texts]. Edited by Weizhong Pu, Kangyun Gong, Zhenbo Yu, Yongming Chen and Xiangkui Yang. Beijing: Peking University Press, p. 457ff. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircae. 1964. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Yuguang. 2022. The Northern Shaman. In Shamanic and Mythic Cultures of Ethnic People of Northern China II: Shamanic Divination, Myths, and Idols. New York: Routledge, pp. 148–64. [Google Scholar]

- Heyne, F. Georg. 1999. The Social Significance of the Shaman among the Chinese Reindeer-Evenki. Asian Folklore Studies 58: 377–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, Lionel Charles. 1945. The Shaman or Chinese Wu: His Inspired Dancing and Versatile Character. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 1945: 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keightley, David. 1998. Shamanism, Death, and the Ancestors: Religious Mediation in Neolithic and Shang China (ca. 5000–1000 B.C.). Asiatische Studien 52: 763–832. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Fushi. 2016. Wuzhe de Shijie [The World of Wu]. Guangzhou: Guangdong Renmin. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Fu-Shih. 2009. The Image and Status of Shamans in Ancient China. In Early Chinese Religion, Vol. 1: Part One: Shang through Han (1250 BC–220 AD). Edited by John Lagerwey and Marc Kalinowski. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Leiden: Brill, vol. 21-1, pp. 397–458. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Liang. 2022. Can Wu and Xi in Guoyu Be Categorised as Shamans? Religions 13: 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, Victor. 1990. Old Sinitic *MYag, Old Persian Magus, and English ‘Magician’. Early China 15: 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, Thomas. 2015. Shamanism Theory and the Early Chinese Wu. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 83: 649–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, George, and Doug White. 2006. Standard Cross-cultural Sample. On-line edition. UC Irvine: Social Dynamics and Complexity. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/62c5c02n (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Puett, Michael. 2002. To Become a God: Cosmology, Sacrifice, and Self- Divinization in Early China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Feng. 2018. Two Faces of the Manchu Shaman: ‘Participatory Observation’ in Western and Chinese Contexts. Religions 9: 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schafer, Edward. 1951. Ritual Exposure in Ancient China. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 14: 130–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuowen Jiezi, Gulin. 2014. Commentaries of Shuowen Jiezi. Edited by Fubao Ding. Beijing: Zhonghua, pp. 5020–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhu, Gopal. 2012. The Shaman and the Heresiarch: A New Interpretation of the Li Sao. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Takigawa, Kametaro. 2015. Shiji Huizhu Kaozheng [Commentaries on the Grand Scribe’s Records]. Edited by Haizheng Yang. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji, pp. 4206–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Enzheng. 2002. Magicians, Magic and Shamanism in Ancient China. Journal of East Asian Archaeology 4: 27–73. [Google Scholar]

- von Falkenhausen, Lothar. 1995. Reflections on the Political Role of Spirit Mediums in Early China: The Wu Officials in the Zhou Li. Early China 20: 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Nicholas. 2020. Shamans, Souls, and Soma: Comparative Religion and Early China. Journal of Chinese Religions 48: 147–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelman, Michael, and Doug White. 1987. A Cross-cultural Study of Magico-religious Practitioners and Trance states: Data base. In Human Relations Area Files Research Series in Quantitative Cross-Cultural Data. Edited by David Levinson and Roy Wagner. New Haven: HRAF Press, vol. 3, pp. i–106. [Google Scholar]

- Winkelman, Michael. 1986. Magico-religious Practitioner Types and Socioeconomic Conditions. Behavior Science Research 20: 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelman, Michael. 1990. Shaman and Other ‘Magico-religious Healers’: A Cross-cultural Study of their Origins, Nature, and Social Transformation. Ethos 18: 308–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelman, Michael. 1992. Shamans, Priests, and Witches. Tempe: Arizona State University Anthropological Research Papers #44. [Google Scholar]

- Winkelman, Michael. 2009. Shamanism and the Origins of Spirituality and Ritual Healing. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture 34: 458–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelman, Michael. 2010a. Shamanism: A Biopsychosocial Paradigm of Consciousness and Healing, 2nd ed. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. [Google Scholar]

- Winkelman, Michael. 2010b. The Shamanic Paradigm: Evidence from Ethnology, Neuropsychology and Ethology. Time and Mind 3: 159–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelman, Michael. 2011. Shamanism and the Alteration of Consciousness. In Altering Consciousness Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Volume 1: History, Culture and the Humanities. Edited by Etzel Cardena and Michael J. Winkelman. Santa Barbara: Preager ABC-CLIO, pp. 159–80. [Google Scholar]

- Winkelman, Michael. 2015. Shamanism as a Biogenetic Structural Paradigm for Humans’ Evolved Social Psychology. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 7: 267–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelman, Michael. 2017. Shamanism and the Brain. In Religion: Mental Religion. Edited by Niki Clements. New York: MacMillan, pp. 355–72. [Google Scholar]

- Winkelman, Michael. 2018. Shamanism and Possession. In The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Edited by Hilary Callan. Hoboken: Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelman, Michael. 2021a. A Cross-cultural Study of the Elementary Forms of Religious Life: Shamanistic Healers, Priests, and Witches. Religion, Brain & Behavior 11: 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Winkelman, Michael. 2021b. The Evolutionary Origins of the Supernatural in Ritual behaviors. In The Supernatural After the Neuro-turn. Edited by Pieter F. Craffert, John R. Baker and Michael J. Winkelman. London: Routledge, pp. 48–68. [Google Scholar]

- Winkelman, Michael. 2021c. The Supernatural as Innate Cognitive Operators. In The Supernatural After the Neuro-turn. Edited by Pieter F. Craffert, John R. Baker and Michael J. Winkelman. London: Routledge, pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Winkelman, Michael. 2021d. Shamanic alterations of consciousness as sources of supernatural experiences. In The Supernatural after the Neuro-Turn. Edited by Pieter F. Craffert, John R. Baker and Michael J. Winkelman. London: Routledge, pp. 127–47. [Google Scholar]

- Winkelman, Michael. 2022. An Ethnological Analogy and Biogenetic Model for Interpretation of Religion and Ritual in the Past. Journal of Archaeological Method & Theory 29: 335–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Haiyan, and Gerald Murray. 2018. The Evolution of Chinese Shamanism: A Case Study from Northwest China. Religions 9: 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, Yuanhao. 2002. Guoyu Jijie [A Commentary on Guoyu]. Edited by Shumin Wang and Changyun Shen. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

| Ritualist Type | Principal Magico-Religious Activity | Selection and Training | Social and Political Power | Professional Characteristics | Motive and Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaman (Forager Shaman) | Healing and divination. Protection from spirits and malevolent magic. Hunting magic. Cause illness and death. | Dreams, illness, and signs of spirit’s request. ASC induction, normally vision quest by individual practitioner alone in wilderness. | High social status. Charismatic leader, communal and war leader. Makes sorcery accusations. Ambiguous moral status. | Predominantly male, female secondary. Part time. No group—individual practice with community. Status recognized by clients. | Acts at client request for client, local community. Community-wide ceremony at night. |

| Shaman/Healer (Agricultural Shaman) | Healing and divination. Protection from spirits and malevolent magic. Hunting magic and agricultural rites. Minor malevolent activity. | Vision quest, dreams, illness and spirit requests. Training by group. Ceremony recognizes status. | Moderate social status. Informal political power. Moderate judiciary decisions. Predominantly moral status. | Predominantly male. Part-time. Collective group practice, ceremonies. Specialized role. | Acts at client request. Performance in client group. |

| Healer | Healing and divination. Agricultural and socioeconomic rites. Propitiation. | Voluntary selection, large payments to trainer. Learn rituals and techniques. Ceremony recognizes status. | High socioeconomic status. Judicial, legislative, and economic power. Denounce sorcerers. Life-cycle rituals. Predominantly moral status. | Predominantly male, female rare. Full-time. Collective training, practice and ceremony. Highly specialized role. | Acts at client request in client group. Treatment in client group. Participates in collective rituals with Priests |

| Medium | Healing and divination. Protection from spirits and malevolent magic. Agricultural rituals. Propitiation. | Spontaneous possession by spirit. Training in practitioner group. Ceremony recognizes status. | Low socioeconomic status. Informal political power. May designate who are sorcerers and witches. Exclusively moral. | Predominantly female; male secondary/rare. Part-time. Collective group practice. | Acts primarily for clients at client residence. Also participates in public ceremonies. |

| Priest | Propitiation and worship. Protection and purification. Agricultural planting and harvest rites. Socioeconomic rites. | Social inheritance or succession. Political action. Incidental training and/or by group. Ceremony recognizes status. | High social and economic status. Political, legislative, judicial, economic, and military power. Exclusively moral. | Exclusively male. Full-time. Hierarchically organized practitioner group. | Acts to fulfill social functions, calendrical rites. Public rituals. |

| Sorcerer/Witch | Malevolent acts. Kill friends, enemies, neighbors, even kin. Cause illness, death, and economic destruction. | Social labeling/accusation. Attribution of biological inheritance. Innate abilities, self-taught or learned. | Low social and economic status. Exclusively immoral. May be killed. | Male and female. Part-time. Little or no professional organization. | Acts at client’s request or for personal reasons such as envy, anger, jealousy, greed or revenge. Practices in secrecy. |

| Ritualist Type | Supernatural Power/Control of Power | ASC Conditions | ASC Techniques and Characteristics | Healing Concepts and Practices | |

| Shaman (Forager Shaman) | Animal spirits, spirit allies. Spirit power usually controlled. | ASC in training and practice. Soul flight/journey, death-and rebirth, animal transformation. | Isolation, austerities, fasting, chanting, singing, drumming and dancing. Collapse/Unconsciousness. | Soul loss, spirit aggression, sorcery. Physical manipulations, sucking, blowing massaging and extraction. Plant medicines. | |

| Shaman/Healer (Agricultural Shaman) | Animal spirit allies and impersonal power (mana). Spirit control, spells, charms, exuvial and imitative. Power controlled. | ASC in training and practice. Shamanic and mystical ASC. Some have soul flight, animal transformation. | Isolation, austerities, fasting, chanting, singing, drumming and dancing. Collapse and unconsciousness. | Extraction and exorcism, countering spirit aggression. Physical manipulations, massage. Plant medicines. | |

| Healer | Superior gods and impersonal power (mana). Charms, spells, rituals, formulas and sacrifice. Propitiate & command spirits. | ASC induction limited. No apparent ASC. | Social isolation; fasting; minor austerities; limited singing, chanting or drumming. | Exorcism and prevent illness. Physical manipulation of body, empirical medicine, imitative and exuvial techniques. | |

| Medium | Possessing spirits dominate. Propitiation and sacrifices. Power dominates, out of control, unconscious. | ASC in training and practice. Possession ASC. | ASC induced through singing, drumming, and dancing. Tremors, convulsions, seizures, compulsive behavior, amnesia, dissociation. | Possession and exorcisms. Control of possessing spirits. | |

| Priest | Power from ancestors, superior spirits or gods. Impersonal power and ritual knowledge. Propitiation and sacrifices. No control over spirit power. | Generally no ASC apparent or very limited. | Occasionally alcohol, sexual abstinence, isolation, sleep deprivation. | Purification and protection. Public rituals and sacrifices. | |

| Sorcerer/Witch | Power from spirits and ritual knowledge. Contagious, exuvial and imitative magic, spells. Power can be unconscious, out of control. | Indirect evidence of ASC in reported flight and animal. transformation. | Night-time activities. | Illness by consuming victim’s soul, spirit aggression, magical darts that enter victim, unconscious emotional effects of envy, anger, etc. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Winkelman, M.J. Chinese Wu, Ritualists and Shamans: An Ethnological Analysis. Religions 2023, 14, 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070852

Winkelman MJ. Chinese Wu, Ritualists and Shamans: An Ethnological Analysis. Religions. 2023; 14(7):852. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070852

Chicago/Turabian StyleWinkelman, Michael James. 2023. "Chinese Wu, Ritualists and Shamans: An Ethnological Analysis" Religions 14, no. 7: 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070852

APA StyleWinkelman, M. J. (2023). Chinese Wu, Ritualists and Shamans: An Ethnological Analysis. Religions, 14(7), 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14070852