The Discourse of Christianity in Viktor Orbán’s Rhetoric

Abstract

:1. Introduction—Questionable Evidence

‘[…] the combination of victimhood, self-confidence, and the resentment against the West; the transformation of neighbor-hating nationalisms into a civilizationist anti-immigrant platform; the delegitimization of civil society and the belief in a strong state; the resurrection of Christian political identity; the adaptation of conspiracy theories; and the transformation of populist discourse into a language and organizational strategy that is compatible with governmental roles’.

‘The historical skirmishes have been replaced by the civilizational conflict that is about the survival of Christian culture, nations, nation-states and traditional families. The fight against the threats of an imminent cultural catastrophe, and against foreign interference, require a common front’.

Research Questions

2. Theoretical Approaches

2.1. Canovan, Mudde, and Laclau

‘The emergence of the ‘people’ as a historical actor is thus always transgressive vis-a-vis the situation preceding it. This transgression is the emergence of a new order’.

2.2. Threats and Securitization

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Methods

4. Results

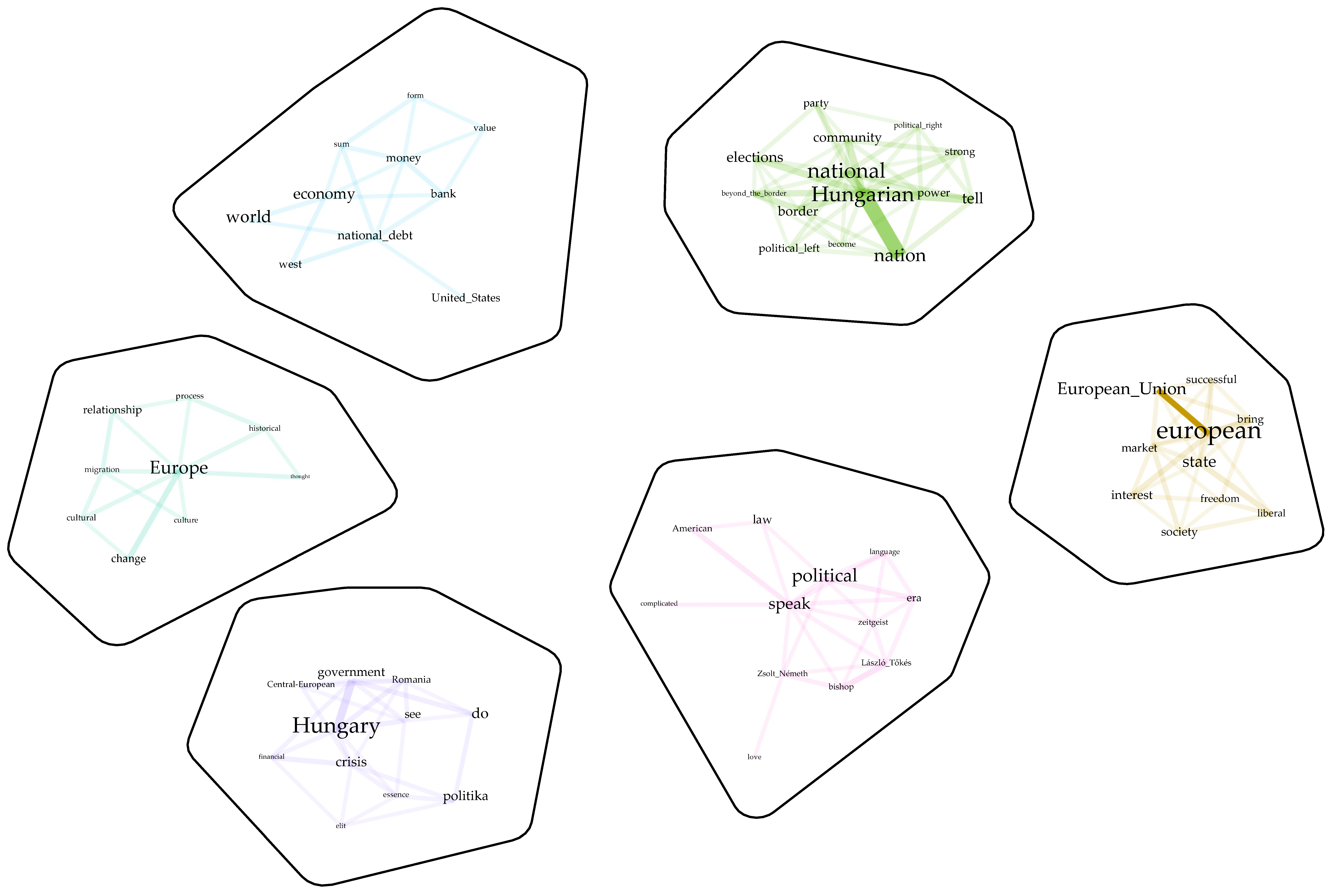

4.1. Discourse Areas of the Tusványos Speeches

- In the first topic, the central words are Hungarian, nation, and national. The terms in the word group refer to the Hungarian parliamentary elections, the sense of community with Hungarians living beyond Hungary’s borders, the sense of belonging together, and the strong right wing, the representation of right-wing values.

- The second topic contains the words European and European Union, highlighted. In addition to these, the words interest, market, state, society, freedom, and successful are also included.

- The third topic contains typical words from politics, political speech, language, laws, different political eras, and zeitgeist.

- The fourth topic focuses on Hungary, Romania, Central Europe, the financial situation, the crisis, among other things, referring to what and how the government and its policies see and do to solve issues.

- Europe is the dominant term in the fifth topic, and other dominant terms include history, culture, change, processes, and relationships that can be observed in Europe. Migration, for example, is also a characteristic word within this theme.

- One of the keywords in the sixth topic is economy, and the world, the United States, among other words such as banks and government.

- The central words of the first topic are Hungarian, national, border and beyond the border (referring to the territories that used to belong to Hungary). The terms in the word group also include hits for civic and political left. It is interesting to note how this translates into a sense of community, belonging, and a strong right-wing representation of right-wing values in the overall analysis over the whole period under study, especially compared to what was obtained in the opposition period, in the present model (civic, left).

- The second topic contains the words zeitgeist, social, market, funding, and union. It is noticeable that, compared to the general picture, different foci dominate in the opposition period.

- The most prominent words in the third topic are Hungary, European, NATO, government, and accession. This topic also looks at the issues of joining the European Union and NATO.

- The fourth topic contains the words Europe, politics, political, change, order, essence, and right-wing. The theme discusses the role of the political right in Europe.

- The word world is a typical one for the fifth topic, besides culture and expressions referring to emotions, such as the verb feel.

- The dominant words in the sixth theme are nation, economy, competitiveness, society, social, and integration.

- The prominent words of the first topic are Hungarian, Hungary, election, parliament, government, and the communication of what its representatives say. Similarities can be observed with the related topics of the general model.

- The second topic contains the words state, Central European, liberal, and successful.

- In the third one, the words of the economic dimension come to the fore as they have been presented in all the other topic models earlier. The dominant words are economy, bank, money, national debt, and value.

- The fourth theme refers to the crisis, institutions, and discussions around the potential solutions, with the verb speak.

- In the fifth topic, the words Europe, nation, national, strong, and community appear, along with the term Christian. This theme is of particular importance for our research, as will be discussed in more detail below.

- The sixth topic contains the words Europe, European Union, policy, political, decision, and action.

4.2. The Discourse of Christianity

‘Because it is true that these Christian Democrat or Conservative governments have been formed, but they have never been able, perhaps they have never dared, to change the spirit of the times themselves, and this spirit of the times has prevailed, if not unhindered, then dominantly, until recently’.

‘I think Hungary is predestined by its history to play this role. The fact that Hungary has always been in turmoil, that every military route has passed through us, that we were influenced by Roman Christianity from the south-west, then by the Reformation from the north, then by Orthodoxy from the other direction, then by Islam from the third or fourth direction, and all of these somehow appeared, influenced and passed through Hungary, and from all of this a great deal of turmoil, misery and pain has resulted. But at the same time, it made our minds extremely sharp and sophisticated’.

‘In Christian Europe, work had honor, a person had dignity, men and women were equal, the family was the foundation of the nation, the nation was the foundation of Europe, and the states guaranteed security. In today’s open society Europe, there are no borders, European people are interchangeable with immigrants, the family has become a form of coexistence that can be varied at will, the nation, national consciousness, and national feeling are negative and transcendable, and the state no longer guarantees security in Europe’.

‘Liberal democracy is in favor of multiculturalism, and Christian democracy gives priority to Christian culture, which is an illiberal idea. Liberal democracy is pro-immigration, Christian democracy is anti-immigration, which is a real illiberal idea. And liberal democracy is pro-variable family models, and Christian democracy is based on the Christian family model, which is also an illiberal idea’.

5. Discussion

‘In other words, we do not yet know exactly whether we are at a moment of transition of a culture, as the ancient culture has given way to the later, subsequent Christian culture […]’.

‘The world is changing, and if the world is changing, it is a major challenge for all nations. Competitive nations will stay afloat and find the right answers, while uncompetitive nations will be plunged into a serious crisis that could threaten their very existence’.

‘Europe must find a way to ensure that this descent is not drastic, that it is bearable, that it stops at a certain point, and that Europe, and our Christian civilization, takes a place on the world economic and military map that offers us security and prosperity, or at least the chance of it. This is what we must fight for today’.

‘Christian democratic politics means defending the forms of existence that have grown out of Christian culture, not the principles of faith, but the forms of existence that have grown out of it. That is human dignity, that is the family, that is the nation’.

The Securitisation Dimension

‘The final question is this: do Christian culture and Christian freedom need to be protected? My answer is that there are two attacks on Christian freedom today. The first comes from within, from the liberals: to abandon the Christian culture of Europe. And there is an attack from outside, which is embodied in migration, which has, if not the aim, the consequence of destroying the Europe we know as Europe’.

‘A modern European individual cannot be a total and unreserved accepter and admirer of their culture, their inherited culture, just as they cannot be a total rejecter and a rebel against it, they experience both at the same time’.

‘Do not be afraid, fight! […] For what is there to fight against? If we cannot define what to fight against, we cannot define what is a good form of fighting, what is expedient and what is counterproductive, we cannot choose the means. If we cannot say what we are fighting against, then we do not know which means are expedient and which are more likely to harm us. That is why it is important that we try—and I think this is the most important task for Europe in the coming year—to define together, at the European level, what we have to fight against’.

‘[…] to summarize what I have said so far, Europe has lost its global role, it has become a regional player, it cannot protect its own citizens, it cannot protect its own external borders, it cannot keep the community together, because the United Kingdom has just left. What more do we need to say that European political leadership has failed? It cannot achieve a single one of its objectives […]’.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antal, Attila. 2019. The Rise of Hungarian Populism: State Autocracy and the Orbán Regime. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Balassa, Bernadett, Miklós Gyorgyovich, and András Máté-Tóth. 2022. A vallási szekuritizáció és a sebzett kollektív identitás modellje a magyar társadalomban empirikus adatok alapján. REPLIKA 127: 131–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcsa, Krisztina, and András Máté-Tóth. 2022. Varieties of Populism in Hungary. Societal and Religious Discourses Regarding the Refugee Crisis. In Populism and Migration. Edited by Éva Gedő and Éva Szénási. Paris: L’Harmattan, pp. 144–60. Available online: https://m2.mtmt.hu/api/publication/33055757 (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Barša, Pavel, Zora Hesová, and Ondřej Slačálek, eds. 2021. Central European Culture Wars, 1st ed. Vol. 15th Volume. Humanitas. Prague: Faculty of Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Bíró-Nagy, András, ed. 2023. A Világ Magyar Szemmel. Külpolitikai Attitűdök Magyarországon 2023-Ban. Budapest: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung—Policy Solutions. [Google Scholar]

- Blei, David M., and John D. Lafferty. 2009. Topic models. In Text Mining. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC, pp. 101–24. [Google Scholar]

- Boda, Zsuzsanna, and Zsófia Rakovics. 2022. Orbán Viktor 2010 és 2020 közötti beszédeinek elemzése: A migráció témájának vizsgálata. Szociológiai Szemle 32: 46–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canovan, Margaret. 1999. Trust the people! Populism and the two faces of democracy. Political Studies 47: 2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Xueqi, Xiaohui Yan, Yanyan Lan, and Jiafeng Guo. 2014. BTM: Topic Modeling over Short Texts. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 26: 2928–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawadi, Saraswati, Sagun Shrestha, and Ram A. Giri. 2021. Mixed-Methods Research: A Discussion on Its Types, Challenges, and Criticisms. Journal of Practical Studies in Education 2: 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, Frank. 2004. Populismus. Edited by Volker J. Kreyher. (Hrg.) Handbuch politisches Marketing: Impulse und Strategien für Politik, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Baden-Baden: Nomos, pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Elliker, Florian. 2013. Demokratie in Grenzen. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyedi, Zsolt. 2020. Right-Wing Authoritarian Innovations in Central and Eastern Europe. East European Politics 36: 363–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Király, Gábor, Ildikó Dén-Nagy, Zsuzsanna Gering, and Beata Nagy. 2014. Kevert módszertani megközelítések. Elméletek és módszertani alapok. KULTÚRA ÉS KÖZÖSSÉG 2: 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kollár, Dávid, and Tamás László. 2022. Megfogyva bár, de törve nem? Erdélyi Társadalom 20: 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, Eszter Krasznai, Kavita Ramakrishnan, and Tatiana Thieme. 2022. Provincializing European Responses to the Refugee ‘Crisis’ through a Hungarian Lens. Political Geography 98: 102708. [Google Scholar]

- Kulska, Joanna. 2023. The Sacralization of Politics? Religions 14: 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laclau, Ernesto. 2002. The Populist Reason. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Lamour, Christian. 2022. Orbán Urbi et Orbi. Politics and Religion 15: 317–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máté-Tóth, András. 2019. Freiheit Und Populismus: Verwundete Identitäten in Ostmitteleuropa. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. [Google Scholar]

- Máté-Tóth, András. 2020. Wounded Words in a Wounded World: Opportunities for Mission in Central and Eastern Europe Today. Mission Studies 37: 354–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máté-Tóth, András, and Bernadett Balassa. 2022. A traumatizált társadalmi tudat dimenziói. Adatok a sebzett kollektív identitás elméletéhez. Szociológiai Szemle 32: 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Máté-Tóth, András, and Réka Szilárdi. 2023. Securitization and Religion in Central and Eastern Europe. In Service for a Servant Church. Outlines and Challenges for Catholic Theology Today. Edited by Gunter M. Prüller-Jagenteufel, Ruben C. Mendoza and Gertraud Ladner. Paderborn: Brill|Schöningh, pp. 147–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, Philipp. 2000. Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research [On-Line Journal]. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/215666096_Qualitative_Content_Analysis (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Mouffe, Chantal. 2018. Für Einen Linken Populismus. Erste Auflage, Deutsche Erstausgabe. Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag, vol. 2729. [Google Scholar]

- Mouffe, Chantal. 2022. Towards a Green Democratic Revolution. London and New York: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rakovics, Zsófia. 2022. Demonstrating potentials in the application of the Temporal Positive Pointwise Mutual Information (TPPMI) temporal word-embedding model—The change in meaning of the words in the prime ministers’ speeches. In Van Új a Nap Alatt: Az ELTE Angelusz Róbert Társadalomtudományi Szakkollégium Konferenciájának Tanulmánykötete. Budapest: Eötvös Loránd University, pp. 31–48. Available online: https://m2.mtmt.hu/api/publication/32926852 (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Sükösd, Miklós. 2022. Victorious Victimization: Orbán the Orator—Deep Securitization and State Populism in Hungary’s Propaganda State. In Populist Rhetorics: Case Studies and a Minimalist Definition. Berlin: Springer, pp. 165–85. [Google Scholar]

- Tusványos speech. 2007. Viktor Orbán’s speech in Tusnádfürdő. Available online: http://2010-2015.miniszterelnok.hu/beszed/orban_viktor_tusnadfurd_337_i_beszede (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Tusványos speech. 2008. Viktor Orbán’s Presentation of the XIX Bálványosi Summer Free University, Tusnádfürdő. Available online: http://2010-2015.miniszterelnok.hu/beszed/helyre_kell_allitani_a_szocialis_egyensulyt (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Tusványos speech. 2010. Viktor Orbán’s Speech at the XXI Bálványosi Summer Free University and Student Camp, Tusnádfürdő (Bǎile Tuşnad). Available online: http://2010-2015.miniszterelnok.hu/beszed/a_nyugati_tipusu_kapitalizmus_kerult_valsagba (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Tusványos speech. 2012. Viktor Orbán’s Speech at the XXIII Bálványosi Summer Free University and Student Camp, Tusnádfürdő. Available online: http://2010-2015.miniszterelnok.hu/beszed/a_jo_romaniai_dontes_tavolmaradni_az_urnaktol (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Tusványos speech. 2013. Viktor Orbán’s Speech at XXIV Bálványosi Summer Free University and Student Camp, Tusnádfürdő (Băile Tuşnad). Available online: http://2010-2015.miniszterelnok.hu/beszed/a_kormany_nemzeti_gazdasagpolitikat_folytat (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Tusványos speech. 2014. Viktor Orbán’s Speech at the XXV At Bálványosi Summer Free University and Student Camp, July 26. Tusnádfürdő (Băile Tuşnad). Available online: http://2010-2015.miniszterelnok.hu/beszed/a_munkaalapu_allam_korszaka_kovetkezik (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Tusványos speech. 2015. Viktor Orbán’s Performance at the XXVI Bálványosi Summer Free University and Student Camp. Available online: http://2010-2015.miniszterelnok.hu/beszed/orban_viktor_eloadasa_a_xxvi._balvanyosi_nyari_szabadegyetem_es_diaktaborban (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Tusványos speech. 2016. Viktor Orbán’s Performance at the XXVII Bálványosi Summer Free University and Student Camp. Available online: https://miniszterelnok.hu/orban-viktor-eloadasa-a-xxvii-balvanyosi-nyari-szabadegyetem-es-diaktaborban/ (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Tusványos speech. 2017. Hungary Performs Better. Available online: https://miniszterelnok.hu/orban-viktor-beszede-a-xxviii-balvanyosi-nyari-szabadegyetem-es-diaktaborban/ (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Tusványos speech. 2018. Orbán Viktor beszéde a XXVIII Bálványosi Nyári Szabadegyetem és Diáktáborban. Available online: https://miniszterelnok.hu/orban-viktor-beszede-a-xxix-balvanyosi-nyari-szabadegyetem-es-diaktaborban/ (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Tusványos speech. 2019. Orbán Viktor beszéde a XXX Bálványosi Nyári Szabadegyetem és Diáktáborban. Available online: https://miniszterelnok.hu/orban-viktor-beszede-a-xxx-balvanyosi-nyari-szabadegyetem-es-diaktaborban/ (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Tusványos speech. 2022. Orbán Viktor Előadása a XXXI Bálványosi Nyári Szabadegyetem és Diáktáborban. Available online: https://2015-2022.miniszterelnok.hu/orban-viktor-eloadasa-a-xxxi-balvanyosi-nyari-szabadegyetem-es-diaktaborban/ (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Visnovitz, Péter, and Erin Kristin Jenne. 2021. Populist Argumentation in Foreign Policy: The Case of Hungary under Viktor Orbán, 2010–2020. Comparative European Politics 19: 683–702. [Google Scholar]

- Wijffels, Jan, Xiaohui Yan, Jiafeng Guo, Yanyan Lan, and Xueqi Cheng. 2023. BTM: Biterm Topic Models for Short Text. In R Documentation. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/BTM/index.html (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Yan, Xiaohui, Jiafeng Guo, Yanyan Lan, and Xueqi Cheng. 2013. A Biterm Topic Model for Short Texts. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on World Wide Web. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 1445–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Keyword (More Frequent) |

Absolute Frequency |

Keyword (Less Frequent) |

Absolute Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Christian | 51 | creed | 4 |

| Christian Democrat | 19 | religion | 3 |

| Christian Democracy | 14 | religious | 2 |

| Islam | 10 | church | 2 |

| Muslim | 9 | faith_in_God | 2 |

| good God | 7 | faith_based | 2 |

| faith | 7 | Church | 2 |

| Christianity | 6 | post-Christian | 1 |

| orthodoxy | 1 | ||

| Orthodox | 1 | ||

| Muslimized | 1 | ||

| de-Christianization | 1 | ||

| Christian-centered | 1 | ||

| baptism | 1 | ||

| de-Christianized | 1 | ||

| by_the_Church | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Máté-Tóth, A.; Rakovics, Z. The Discourse of Christianity in Viktor Orbán’s Rhetoric. Religions 2023, 14, 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081035

Máté-Tóth A, Rakovics Z. The Discourse of Christianity in Viktor Orbán’s Rhetoric. Religions. 2023; 14(8):1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081035

Chicago/Turabian StyleMáté-Tóth, András, and Zsófia Rakovics. 2023. "The Discourse of Christianity in Viktor Orbán’s Rhetoric" Religions 14, no. 8: 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081035

APA StyleMáté-Tóth, A., & Rakovics, Z. (2023). The Discourse of Christianity in Viktor Orbán’s Rhetoric. Religions, 14(8), 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14081035