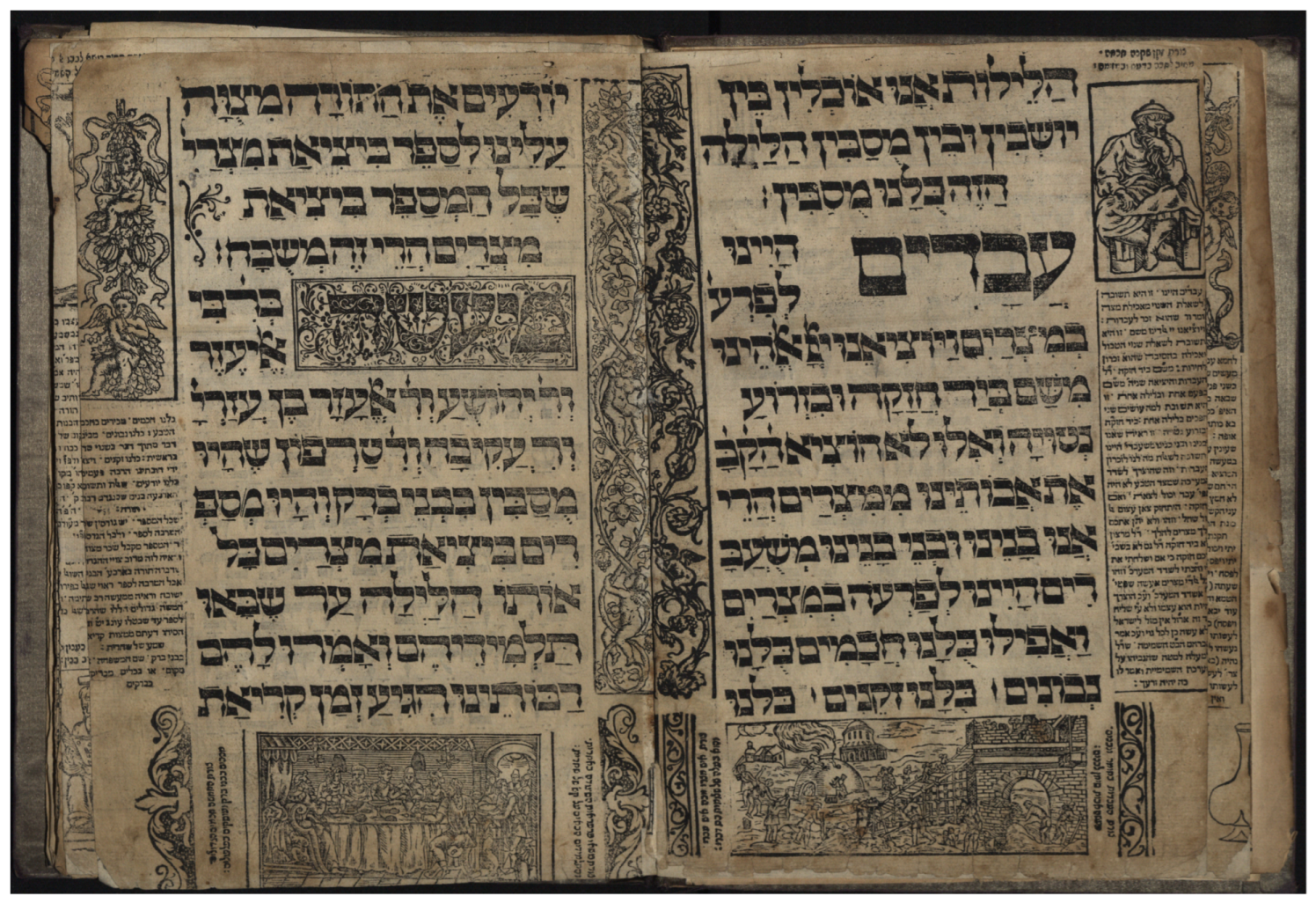

An Illustrated Haggadah for Sefardi Exiles in Istanbul

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Historiography: Attribution

2. Materials and Methods: A New Pictorial Program

3. Discussion

3.1. The Rationale of the Illustration Program

Further, how exactly is “bnei braq” to be understood? Why did the Rabbis remain awake during the whole night? Why did they not feast with their families? Were the Rabbis staying in a town “baraq” and feasting with the citizens (“the sons”—bnei) of that town? Were they being hosted by different families?A story about Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Joshua etc. The compiler of the haggadah (hamaggid) wanted to bring evidence for [the saying] that the one who adds to the narration of the departure from Egypt is to be praised; [this applies] even to scholars and wise men and those who know the entire Torah; this is what occurred to the five giants of their generation, to the Sages of Israel on the night of Passover when they reclined in bnei braq.(Abarbanel, ZP 1505, fol. 8b)

Hence, in contrast to the actual text of the haggadah, and with the help of allegorical interpretation, Abarbanel focused on the Rabbis performing ritual acts, with the understanding that the narration of the Exodus itself is a ritual act. Against this background, the depiction of the Rabbis performing the seder makes complete sense.[T]hese saints did as they (the Israelites) did; at the beginning they occupied themselves with the laws of unleavened bread and bitter herbs (מצות מצה ומרור) and the commemoration of the Passover, as did our fathers in Egypt, and then for the rest of the night they kept telling the story of departure; that is how they saw themselves as if they were departing [from Egypt].(Abarbanel, ZP 1505, fol. 8b)

[…] Of all the plagues that occurred in Egypt there were three that were performed by Aaron by means of the rod, and they are: blood, frogs, and lice; and three of them were brought forth by the Holy One Blessed be He, not with the aid of Moses and not with the aid of Aaron, and they are: ‘arov, murrain, and the death of firstborn […]. Three other [plagues] were performed by Moses, our teacher, be peace upon him, and they were: hail, locusts, and darkness, and one plague was performed by Moses and Aaron together: boils.(Abarbanel, Perush hatorah 1997, vol. 2, pp. 124–25)

The woodcut also emphasizes the conversation between Pharaoh and his magicians about the latter’s attempts to imitate the plagues. The plague of lice was the first that the magicians were unable to reproduce. Exodus 8:14–15 reads: “The magicians did the like with their spells to produce lice, but they could not; and lice were upon man, and upon beast; and the magicians said to Pharaoh: This is the finger of God” (translation: JPS 1985). Abarbanel’s Commentary to the Book of Exodus elaborates on this conversation, emphasizing that the magicians realized that Moses and Aaron did not perform sorcery but that the plague was brought about by divine power (Abarbanel, Perush hatorah 1997, vol. 2, p. 122). The image in fact shows Pharaoh gesturing with his left hand in what seems to be a rebuke to the magicians, whose statement about God’s finger turns here into an apology.[…] The (plague) of lice was different from the (plague) of blood insofar as blood occurred (only) on those places that Aaron touched (with the rod). […] Rather, Aaron stroked the soil of the earth once and everywhere in Egypt the dust turned into lice, and that is why it is written: all the dust of the earth turned to lice throughout the Land of Egypt (Exod. 8:13). This means that with only one stroke that Aaron performed with his rod onto the dust of the earth lice came about everywhere in Egypt […] the rod in his (Aaron’s) arm hinted at the four cardinal points as well as up and down so that the plague would occur everywhere. […] This also explains, as I mentioned, that Scripture says: lice came upon man and beast; all the dust of the earth turned to lice (Exod. 8:13). This means that two different things happened at the time of this plague: firstly, lice came upon man and beast; note that here the word “all” does not appear, as in the phrase “all the dust of the earth”. […] This means that all the men and all the beasts that were near Aaron at the time the plague occurred were infested with lice, but not the rest of the men and beasts throughout the Land of Egypt; but this does not apply to the dust, because [the mention] of all the dust means that there were lice everywhere that dust is found nearby or far away […].(Abarbanel, Perush hatorah 1997, vol. 2, p. 121)

3.2. A Haggadah for Sefardi Refugees

[…] I said [to myself] it is time to prepare an encompassing commentary on the stories of the Passover [that deal] with the exile and its causes and with the various ways of redemption and its wonders, […] and I will entitle my tract “Passover Sacrifice”, because it is my sacrifice to God from a broken spirit […](Abarbanel, ZP 1505, fol. 2a)

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Shelf Numbers of the Fragments

| Edition A | Edition B |

|---|---|

| Taylor-Schechter Genizah Research Unit | |

| AS 191.500 | AS 196.110 |

| AS 196.273 | AS 196.111 |

| AS 197.318 (copy of RB 5637.1) | AS 196.212 |

| AS 197.382 | AS 196.312 A * |

| AS 197.415 | AS 196.312 B * |

| NS 168.4 | AS 196.321 |

| NS 168.5A | AS 196.322 |

| NS 168.5B | AS 196.381 |

| NS 168.6 | AS 196.446 |

| NS 168.18 | AS 196.448 |

| Misc. 19.61 P2 | AS 197.145 |

| Misc. 30.8A | AS 197.157 |

| AS 197.165 | |

| AS 197.173 | |

| AS 197.247 | |

| AS 197.255 | |

| AS 197.277 | |

| AS 197.323-L1 | |

| AS 197.323-L2 | |

| AS 197.323-L3 | |

| AS 197.323-L4 | |

| AS 197.381 | |

| AS 197.418 | |

| Misc. 19.61 P1 | |

| Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary | |

| RB 5637.1 (copy of AS 197.318) | RB 5637.3 |

| RB 5637.2 | |

References

Manuscripts and Early Prints

Haggadah, Guadalajara, National Library of Israel (henceforth NLI), Schocken 68. https://www.nli.org.il/en/books/NNL_ALEPH001312630/NLI (accessed on 14 September 2023).Haggadah, Istanbul 1505 (?), for Digitizations, see Cambridge, The Taylor-Schechter Genizah Research Unit. https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/collections/genizah/1 (accessed on 14 September 2023), and the Friedberg Jewish Manuscript Society. https://fjms.genizah.org/?eraseCache=true (accessed on 14 September 2023).Haggadah, Mantua 1568, Cincinnati, Hebrew Union College Library, RBR B 2058, https://mss.huc.edu/ajaxzoom/single.php?zoomDir=/pic/zoom/printed_material/RBR_B_2058 (accessed 14 September 2023).Haggadah, Rome 1508 Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica, NLI, Microfilm 93 F 1 Haggadah, Rome 1508.Haggadah, Venice 1599, Zurich, Collection of David Jeselsohn. https://www.nli.org.il/en/books/NNL_ALEPH001062914/NLI (accessed on 14 September 2023).Haggadah, Venice 1601, NLI, A 75 R706. https://www.nli.org.il/en/books/NNL_ALEPH001077403/NLI (accessed on 14 September 2023).Haggadah, Venice 1605, Zurich, Collection of David Jeselsohn. https://www.nli.org.il/en/books/NNL_ALEPH001062912/NLI (accessed on 14 September 2023).Mashmi‘a yeshu‘ah, Salonica 1526, NLI A75 R36. https://www.nli.org.il/en/books/NNL_ALEPH001088690/NLI (accessed on 14 September 2023).Merkevet hamishneh, Sabbioneta 1551, Zurich, Collection of David Jeselsohn. https://www.nli.org.il/en/books/NNL_ALEPH001088689/NLI (accessed on 14 September 2023).Zevah Pesah, Istanbul 1505, Zurich, Collection of David Jeselsohn. https://www.nli.org.il/en/books/NNL_ALEPH001366943/NLI (accessed on 14 September 2023).Primary Sources

(Abarbanel, Perush hanevi’im 2009) Isaac Abarbanel, 2009. Perush hanevi’im lerabbenu Yitshak Abarban’el, ed. Yehuda ben Moshe Shaviv. Jerusalem: Horev.(Abarbanel, Perush hatorah 1997) Isaac Abarbanel. 1997. Perush hatorah lerabbenu Yitshak Abarban’el, ed. Avishai Shotland. Jerusalem: Horev.(Abarbanel, ZP 1505) Isaac Abarbanel. 1505. Zevah Pesah. Istanbul.(Eleazar ben Juda, Perusah haroqeah 1984) Eleazar ben Judah of Worms. 1984. Haggadah shel Pesah veshir hashirim ‘im perush haroqeah. Edited by Moshe Hershler. Jerusalem: Makhon Shalem.(JPS 1985) Tanakh: The Holy Scriptures. The New JPS Translations According to the Traditional Hebrew Text. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America. 1985.(Zedekia ben Abraham, Shibole haleqet) Zedekia ben Abraham the Physician, Shibole haleqet, Seder Pesah 218. Responsa Project, Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University).Secondary Literature

- Barlow, Jane. 2017. The Muslim Warrior at the Seder Meal. Dynamics between Minorities in the Rylands Haggadah. In Postcolonising the Medieval Image. Edited by Eva Frojmovic and Catherine E. Karkov. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 218–40. [Google Scholar]

- Baruchson-Arbib, Shifrah. 1989. In Search of Lost Books of the 15th–16th Centuries. Alei Sefer 16: 37–57. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Ben Na’eh, Yaron. 2001. Hebrew Printing Houses in the Ottoman Empire. In Jewish Journalism and Printing Houses in the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Edited by Gad Nassi. Istanbul: The Isis Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biale, David. 1986. Power and Powerlessness in Jewish History. New York: Schocken Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, Abraham P. 1978. The Biblical and Historical Background of the Jewish Holy Days. New York: KTAV Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Boyarin, Daniel. 1997. Unheroic Conduct. The Rise of Heterosexuality and the Invention of the Jewish Man. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Skalli, Cedric. 2007. Yitsḥaq Abravanel’s First Edition (Constantinople 1505). Rhetorical Content and Editorial Background. Hispania Judaica Bulletin 5: 153–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Skalli, Cedric. 2021. Don Isaac Abravanel. An Intellectual Biography. Waltham: Brandeis University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frojmovic, Eva. 1996. From Naples to Constantinople: The Aesop Workshop’s Woodcuts in the Oldest Illustrated Printed Haggadah. The Library, Sixth Series 18: 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermann, Abraham M. 1961. The Jewish Art of the Printed Book. In Jewish Art. An Illustrated History. Edited by Cecil Roth. New York, Toronto and London: McGraw-Hill, pp. 464–66. [Google Scholar]

- Habermann, Abraham M. 1962–1963. An Additional Sheet from the Illustrated Haggadah, Constantinople? 1515. Kiryat Sefer 38: 273–76. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Habermann, Abraham M. 1972. Who Printed the First Illustrated Haggadah [Constantinople? 1515?]. Kiryat Sefer 47: 159–61. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, Joseph R. 1972. Sixteenth-Century Prints from Constantinople. Additions, Corrections and Elucidations Based on Abraham Yaari, Hebrew Printing in Constantinople, Jerusalem 1967. Areshet 11: 457–93. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, Joseph R. 1980. Some Letters on the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain and Sicily. In Studies in the History of Jewish Society in the Middle Ages and in the Modern Period Presented to Professor Jacob Katz on his Seventy-Fifth Birthday by His Students and Friends. Edited by Immanuel Etkes and Yoseph Salmon. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, pp. 64–97. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, Joseph R. 1987. The Intellectual Activity of the Jews of the Ottoman Empire during the 16th and 17th Centuries. In Jewish Thought in the Seventeenth Century. Edited by Isidore Twersky. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, pp. 95–135. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, Joseph R. 1989. Wisdom and Depression—Polarities in the Spritial and Social Experience of Sefardi and Portuguese Exiles in the Ottoman Empire. In Culture and Society in Jewish Medieval History. Studies in Memory of Hayyim Hillel ben-Sasson. Edited by Reuven Bonfil, Menahem Ben-Sasson and Joseph Hacker. Jerusalem: Shazar Institute, pp. 541–86. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, Joseph R. 1992. The Sephardim in the Ottoman Empire in the Sixteenth Century. In The Sephardi Legacy. Edited by Haim Beinart. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, vol. 2, pp. 109–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, Joseph R. 2012. Authors, Readers and Printers of Sixteenth-Century Hebrew Books in the Ottoman Empire. In Perspectives on the Hebraic Book. The Myron M. Weinstein Memorial Lectures at the Library of Congress. Edited by Peggy K. Pearlstein. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, pp. 127–63. [Google Scholar]

- Haggada. Das Fragment der Ältesten mit Illustrationen Gedruckten Haggadah. 1926. Berlin: Soncino Gesellschaft.

- Halbertal, Moshe. 2006. Of Pictures and Words: Visual and Verbal Representations of God. In The Divine Image—Depicting God in Jewish and Israeli Art. exh. cat. Jerusalem: Israel Museum, pp. 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Julie. 2005. Good Jews, Bad Jews, and no Jews at All—Ritual Imagery and Social Standards in the Catalan Haggadot. In Church, State, Vellum, and Stone. Essays on Medieval Spain in Honor of John Williams. Edited by Therese Martin and Julie Harris. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 275–96. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, Marvin J. 2021. Yetzi’at Mitzra’im (The Exodus) in Print: The First Editions of the Printed Haggadah. In Essays on the Making of the Early Hebrew Book. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 592–638. [Google Scholar]

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 2006. Illuminated Haggadot from Medieval Spain. Biblical Imagery and the Passover Holiday. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 2017. Designing a Passover Imagery for New Audiences: The Prague Haggadah. In Uniter Druck. Mitteleuropäische Buchmalerei im 15. Jh. Edited by Jeffrey Hamburger and Maria Theisen. Petersberg: Imhof Verlag, pp. 180–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kogman-Appel, Katrin. 2024. Jewish Printers and Christian Artists in Naples. In Co-produced Religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Edited by Katharina Heyden and David Nirenberg. Oxford University Press: in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Lacerenza, Giancarlo. 2002. Lo spazio dell’ebreo. Insediamenti e Cultura Ebraica a Napoli. Secoli XV–XVI. In Integrazione ed Emarginazione. Circuiti e Modelli: Italia e Spagna nei Secoli XV–XVIII. Edited by Laura Barletta. Naples: Istituto Suor Orsola Benincasa—CUEN, pp. 357–427. [Google Scholar]

- Lawee, Eric. 2001. Isaac Abarbanel’s Stance Toward Tradition. Defence, Dissent, and Dialogue. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, Pasquale. 1989. Napoli e la peste 1464–1530. Naples: Juvene. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Vivian B. 1992. Catalogue. In Convivencia. Jews, Muslims, and Christians in Medieval Spain. exh. cat. Edited by Vivian B. Mann, Thomas F. Glick and Jerrilynn D. Dodds. New York: George Braziller and The Jewish Museum, cat. no 51. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Moses. 1947. History and Annals of Hebrew Printing in the Sixteenth Century. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, Mendel. 1973. La Haggadah Enluminée. Étude Iconographique et Stylistique des Manuscrits Enluminés et Décorés de la Haggada du XIIe au XVIe siècle. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Offenberg, Adri K. 1992. A Choice of Corals. Facets of Fifteenth-Century Hebrew Printing. Nieukoop: De Graaf Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Offenberg, Adri K. 1996. Offenberg. The Printing History of the Constantinople Hebrew Incunable of 1493: A Mediterranean Voyage of Discovery. The British Library Journal 22: 221–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, Jonathan. 2008. New Approaches to Jewish Diaspora: The Sephardim as a Sub-Ethic Group. Jewish Social Studies 15: 10–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, Jonathan. 2013a. After Expulsion. 1492 and the Making of Sephardic Jewry. New York and London: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, Jonathan. 2013b. Creating Sepharad: Expulsion, Migration, and the Limits of Diaspora. Journal of Levantine Studies 3: 9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, Jonathan. 2021. Diaspora as Nation. The Mediterranean Sephardim between the Fifteenth and Twentieth Centuries. In The Oxford Handbook of the Jewish Diaspora. Edited by Hasia R. Diner. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 391–408. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, Cecil. 1953. The Borders of the Naples Bible of 1491–1492. The Bodleian Library Record 4: 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Rozen, Minna. 2010. A History of the Jewish Community in Istanbul. The Formative Years, 1453–1566. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Sabar, Shalom. 2019. Typography, Layout and Decoration: The Printed Hebrew Book in the Iberian Peninsula and its Origins in Illuminated Manuscripts. In Sephardic Book Art in the Fifteenth Century. Edited by Luís U. Afonso and Tiago Moita. Lonodn: Harvey Miller abd Tunrhout: Brepols, pp. 59–88. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeper, Silke. 1999. S’ridei Schocken—‘Einbandfragmente’ of Hebrew Incunable and Postincunabula at the Schocken Institute for Jewish Research. In Jewish Studies at the Turn of the 20th Century. Edited by Judit Targarona Borrás and Angel Sáenz-Badillos. Leiden and Boston: Brill, vol. 1, pp. 627–35. [Google Scholar]

- Scheiber, Alexander. 1965. New Pages form the First Printed Illustrated Haggadah. Studies in Bibliography and Booklore 7: 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Scheiber, Alexander. 1982. Who Printed the First Illustrated Haggadah? Kiryat Sefer 57: 165–66. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzer, Menahem H. 2006. Hebrew Incunabula: An Agenda for Research. In Studies in Jewish Bibliography and Medieval Hebrew Poetry. Collected Essays. Edited by Menahem H. Schmelzer. New York and Jerusalem: Jewish Theological Seminary, pp. 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzwald, Ora. 1999. Language Choice and Language Varieties before and after the Expulsion. In From Iberia to Diaspora: Studies in Sephardic History and Culture. Edited by Norman A. Stillman and Yedida K. Stillman. Leiden: Brill, pp. 399–415. [Google Scholar]

- Tabory, Joseph. 2013. The barait’a of the Four Sons. Tarbiz 81: 165–89. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Yaari, Abraham. 1943. Hebrew Printers’ Marks from the Beginning of Hebrew Printing to the End of the 19th Century. Jerusalem: Hebrew University Press Assess. [Google Scholar]

- Yaari, Abraham. 1961. Bibliography of the Passover Haggadah. Jerusalem: Bamberger and Wahrmann. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Yaari, Abraham. 1967. Hebrew Printing in Constantinople. Jerusalem: Magnes Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Yerushalmi, Yoseph H. 1975a. Haggadah and History: A Panorama in Facsimile of Five Centuries of the Printed Haggadah from the Collections of Harvard University and the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America. [Google Scholar]

- Yerushalmi, Yoseph H. 1975b. Leaves from the Oldest Illustrated Printed Haggadah. Reproduced from the Originals in the Adler Collection, The Jewish Theological Seminary of America and the Taylor-Schechter Genizah Collection, Cambridge University. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America. [Google Scholar]

- Yuval, Israel J. 1999. Easter and Passover as Early Jewish-Christian Dialogue. In Passover and Easter. Origin and History to Modern Times. Edited by Paul F. Bradshaw and Lawrence A. Hoffman. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, pp. 178–223. [Google Scholar]

- Zeldes, Nadia. 2017. The Reception of Spanish and Sicilian Exiles by the Populace in the Kingdom of Naples. Zion 82: 37–58. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Zeldes, Nadia. 2019. The Mass Conversion of 1495 in South Italy and its Precedents: A Comparative Approach. Medieval Encounters 25: 227–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kogman-Appel, K. An Illustrated Haggadah for Sefardi Exiles in Istanbul. Religions 2023, 14, 1192. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091192

Kogman-Appel K. An Illustrated Haggadah for Sefardi Exiles in Istanbul. Religions. 2023; 14(9):1192. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091192

Chicago/Turabian StyleKogman-Appel, Katrin. 2023. "An Illustrated Haggadah for Sefardi Exiles in Istanbul" Religions 14, no. 9: 1192. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091192

APA StyleKogman-Appel, K. (2023). An Illustrated Haggadah for Sefardi Exiles in Istanbul. Religions, 14(9), 1192. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14091192