1. Introduction

The increasing societal pluralism and the diversity of religions and worldviews in Swedish early childhood education and care (ECEC, i.e., “preschool”) have effects on what competencies today’s preschool teachers need, thereby requiring updates in the contents taught in Swedish Preschool Teacher Education (PTE). Policy directives for widened admission to all higher education in Sweden (

SCS 1992) also make issues regarding diversity, inclusion, and interculturality increasingly important for PTEs to manage. This also includes the goals regarding social sustainability in higher education and the formulations in the United Nations Agenda 2030 (

UN 2015) that call for inclusive and equitable education at all educational levels. Out of the three dimensions of sustainability covered by the concept of sustainable development or sustainability (see, e.g.,

Johansson and Rosell 2021), this article focuses on social sustainability. Moreover, in the Swedish Higher Education Ordinance, henceforth HEO (

SCS 1993), some goals specifically apply to knowledge and skills that can be considered crucial when it comes to preparing students to promote social sustainability and to work with issues related to religion and worldviews in preschool. In this article, we use the abbreviation ECEC and the term preschool interchangeably.

Religion is, in this article, understood as something that, regardless of its content, can be regarded as a resource, for instance through providing a person support or comfort (

Kuusisto 2022). We use religion and worldview (and religions and worldviews) as partly overlapping concepts, and even though the umbrella term worldview does include religious worldviews, we often use both concepts together. In singular, we talk about the phenomena or the subject of religion as well as the phenomena of worldview or someone’s worldview, and in line with

Kuusisto (

2022) and

Poulter (

2013) we use worldview as an expression of each individual’s unique ontological, ethical, and epistemological way of understanding the world around them. According to this approach, an individual’s worldview is used both when the individual is creating meaning and making choices. In this understanding, even a religious worldview is thus a way of understanding one’s surroundings and one’s place in the world (

Kuusisto 2022;

Poulter 2013). Group values, norms, and knowledge that are expressed in common expressions of what is seen as true or not in a certain context are also understood as aspects of worldviews. Even the construction of a group identity and who is made the subjects or the ‘we’ and who is made objects or ‘the others’ can be included when we use the concept of worldview (cf.

Poulter et al. 2016;

Kuusisto et al. 2021;

Raivio et al. 2022). This is of importance since students’ social and cultural inclusion and a sense of belonging (

Yuval-Davis 2011) are essential aspects of a socially sustainable PTE, including creating an inclusive and just education regarding religion and worldviews. In addition, the students who are trained as preschool teachers in an increasingly multicultural society need to be prepared to be able to offer children in preschool a socially sustainable and inclusive learning environment (cf. how

Berge and Johansson 2021;

Johansson and Rosell 2021;

Raivio et al. 2022, discuss this concerning preschool and children’s sense of belonging), since by doing so, they (when examined preschool teachers) can contribute to children’s well-being and sense of belonging in ECEC.

To talk about the specific set of knowledge and skills needed by teachers in the PTE as well as by preschool teachers in ECEC to achieve the kind of learning environment depicted above, we, in line with

Shaw (

2020), use the concept of religion and worldview literacy (R&W literacy). This includes intercultural competence or can be seen as a part of interreligious competence. Ubani, on the other hand, uses ‘religious literacy’ to define knowledge and skills concerning religion and worldviews educated in public education (

Ubani 2023). Similar to our previous work (

Raivio et al. 2022) Ubani relates ‘religious literacy’ to educating for socially sustainable development. Like both “religious literacy” (

Moore 2007;

Ubani 2023) and “worldview literacy” (

Kimanen 2023), R&W literacy (

Shaw 2020) is a debated concept. ‘Religious literacy’, being the oldest and thus most contested of the three (

Shaw 2020), has been defined both from theological (e.g.,

Wright 1993) and cultural studies (e.g.,

Moore 2007) and educational (

Ubani 2023) approaches to encompass skills of theological and philosophical reflection as well as a person’s knowledge of her own and other religious traditions. Recently,

Kimanen (

2023), in her discussion, proposes the use of the concept of ‘worldview literacy’ as she points to both the need for nonreligious persons to understand religion and the need to recognize their secular standpoint as similarly being a worldview. She defines worldview as a concept that encompasses both “religious and secular systems of meaning that have existential dimension and affect one’s thinking and acting” (

Kimanen 2023, p. 151). Based on this, she chooses to use the concept of worldview literacy. Even though we find the enhancing of students’ awareness that we all create meaning and make choices based upon our worldviews to be most relevant, we here use

Shaw’s (

2020) concept of R&W literacy, including not only knowledge and sensitivity but also a norm-critical ability to see power relations and to analyze and use information reflectively.

In the present study, the curricula from all twenty PTEs in Sweden in 2022 are investigated. Earlier research has, as we will come back to, shown problematic discourses related to ethnicity and diversity in teacher education (e.g.,

Bayati 2014;

Layne and Dervin 2016;

Rosén and Wedin 2018). The present study aims to investigate content and discursive norms regarding religion and worldviews in the PTEs on a national policy level and to contribute knowledge in the research field of PTE, religion, and ECEC. The research questions focus on the content of the educational curricula of the Swedish PTEs on: What conditions and obstacles there might be for (a) dealing with issues related to religion and worldview in works for a socially sustainable, caring, equal, equal, and inclusive higher education and (b) providing relevant educational content to the professional development of future preschool teachers (knowledge, skills, and abilities) regarding social sustainability linked to religion and worldviews in the preschool. The analysis of the actual wordings of the educational curricula, and to what degree religion and worldview are mentioned, is further elaborated by using a theoretical and analytical tool (

Raivio et al. 2022) based on the feminist (

Hooks 2003;

Noddings 2013;

Yuval-Davis 2011), norm-critical (

Kumashiro 2000) and post-colonial (

Powell 2012;

Spivak [1987] 2006) perspectives. In light of the results, the conditions and obstacles that may arise based on the content of the local governing documents studied are highlighted and discussed, and so are the incitements for Swedish PTEs to offer a socially sustainable and inclusive education and provide students the knowledge content and generic skills for developing R&W literacy.

1.1. Swedish Preschool Teacher Education—Historical and Contemporary Context

From a historical perspective, in the 19th century, it was mainly the German pedagogue Friedrich Fröbel who influenced the design of both children’s activities and preschool teacher training in Sweden (

Åman 2014). In 1843, according to

Åman (

2014), Fröbel wrote a curriculum for a kindergarten seminar for so-called child leaders. The Pestalozzi Fröbel Haus in Berlin was one of the courses that were started. Anna Whitlock, Anna Eklund, Maria Kjellmark, and Maria Moberg attended the Pestalozzi training and became the pioneers who built up both kindergarten activities and so-called leadership training in Sweden. In 1899, the first Swedish education for kindergarten teachers was given at the Margareta School-Fröbel Seminary in Stockholm. In 1945, the Preschool Seminars were given a state grant, and in 1960, Sweden had seven preschool teacher training courses that annually examined 230 teachers. In 1963, the seminaries were formalized nationally. The seminar format was maintained until 1977, when preschool teacher education became a university education. Preschool teacher education has thus, according to

Åman (

2014), been a university education for 45 years in Sweden.

The educational content linked to what we today refer to as social sustainability—and thus to issues regarding religion and worldviews has varied. According to

Åman (

2014), the curriculum for PTEs from 1980 emphasizes that education should “give a holistic view of children’s development and understanding of and empathy in their world of experience and upbringing situation” (

Åman 2014, p. 63), continuing that also situations for “families with a different ethnic and cultural, linguistic or religious background, and differences in the situation and conditions of men and women”, must be taken into account according to the curriculum. Finally, according to

Åman (

2014), the curriculum says that during their education, students should process attitudes and values as part of their personal development (

Åman 2014). Equality, solidarity, and international issues were thus central to Swedish PTEs during the 1980s.

Today, PTE degree studies are offered at 20 Swedish universities, and the number of preschool teachers who are examined each year is estimated by

The Swedish Higher Education Authority (

2022, retrieved 7 November 2022) to be approximately 2500. The full-time program runs for 3.5 years (seven semesters) and leads to a BA-level preschool teacher’s degree, which includes 210 higher education credits. Since the 1990s, the PTE’s overall goals have been outlined in the Higher Education Act (henceforth HEA) (

SCS 1992) and the Higher Educational Ordinance (

SCS 1993). When it comes to the requirements for equality and justice in higher education in Sweden, today’s HEA states that:

In their activities, the universities must promote sustainable development, which means that current and future generations are assured of a healthy and sound environment, economic and social welfare, and justice. In the activities of the universities, equality between women and men must always be observed and promoted. The combined international activities at each university must partly strengthen the quality of the university’s education and research and partly contribute nationally and globally to such sustainable development as referred to in the first paragraph.

In addition, among the goals in the Swedish HEO (

SCS 1993) are some that specifically apply to the knowledge and skills of importance when it comes to preparing students to promote social sustainability and work with issues related to religion and worldviews in preschool. For example, they must be able to demonstrate the ability to make judgments based on relevant ethical aspects in the pedagogical work (

SCS 1993). They must also take particular account of human rights, with a focus on the rights of the child according to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (

UN 1989), as well as sustainable development. Furthermore, after they are fully trained, preschool teachers must be able to “prevent and counteract discrimination and other abusive treatment of children”, as well as “take into account, communicate and anchor an equality and equality perspective in the educational activities” (

SCS 1993). Higher education, in this case the PTEs of today, must therefore be carried out in a way that protects the student’s right to a socially sustainable; equal and just study situation. It also has to prepare preschool teacher-students for a profession where they can, in turn, conduct a socially sustainable, equal, and just education in preschool. When it comes to content linked to religion and worldviews, state universities and colleges in Sweden must conduct non-denominational education (

Bexell 2000). The same regulation is made in the curricula for Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) in Sweden (

SNAE 2018).

1.2. The Preschool Teacher Assignment in the Diverse Swedish Preschool

What does the profession of a preschool teacher mean today in terms of knowledge and abilities linked to interculturality, where issues regarding religion and worldviews belong? Sweden, similar to other societies, is increasingly pluralistic, with both “old” and “new” diversity (

Vertovec 2015; see also

Kuusisto and Garvis 2020;

Raivio and Skaremyr 2022), as is the ECEC context and the PTEs. This pluralism also applies to the diversity of religions and worldviews, which is an aspect of diversity that the discourse on multicultural or intercultural education often ignores (

Poulter et al. 2016). Of all children in the population between the ages of one and five in 2022, almost 90% of all children in Sweden were enrolled in preschool. A total of 1/4 of the children in the preschool had a foreign background or two parents born in a country other than Sweden (

SNAE 2023). This means that preschools in Sweden today include a significant amount of diversity, which places high demands on preschool teachers’ ability to make the preschool a socially sustainable, inclusive community of care (

Raivio et al. 2022).

As stated earlier, the UN’s Agenda 2030 (

UN 2015) includes the promotion of inclusive and fair education at all educational levels, therefore also including preschool. According to the UN, preschool must form a basis for lifelong learning (cf.

Samuelsson et al. 2019). In 2020, the Convention on the Rights of the Child was incorporated into Swedish legislation. According to Article 14:1, the convention states must “respect the child’s right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion” (

UN 1989, p. 6). Furthermore, according to Article 27:1, they must recognize “every child’s right to a standard of living that is sufficient for the child’s physical, mental, spiritual, moral and social development” (

UN 1989, p. 12). However, the Curriculum for Preschools in Sweden (

SNAE 2018) says nothing explicitly about the place of religion in preschool (

Raivio and Skaremyr 2022;

Reimers 2019). On the contrary, it says that children in preschool should not be influenced unilaterally in favor of one worldview or another and that the education, therefore, should be “objective, comprehensive and non-confessional” (

SNAE 2018, p. 6). The curricula also state that the preschool must give all children “conditions to develop their cultural identity” (

SNAE 2018, p. 15). When the curriculum is interpreted from an intercultural perspective, however, religion and worldviews can be included as aspects of cultural identity (

Raivio and Skaremyr 2022). Similarly, religion and worldviews can be understood as important aspects where it is stated that preschool must “lay the foundation for children’s understanding of different languages and cultures, including the languages and cultures of the national minorities” (

SNAE 2018, p. 6), as well as promoting children’s awareness of different cultures, and the ability to “understand and empathize with other people’s conditions and values” (

SNAE 2018, p. 6).

In light of the above, it can be said that the demands on today’s preschool teacher training in Sweden are high when it comes to contributing to students’ development of R&W literacy (

Shaw 2020), that is, the knowledge, skills, and abilities future preschool teachers need to be able to conduct a socially sustainable, inclusive, equal and just education in preschool. These skills also include adequate knowledge of different religions and worldviews, a sensitivity to children’s religious, secular, and spiritual expressions, and the ability of critical self-reflectiveness as well as to handle the complexity of dilemmas related to power relations that might arise in the daily work in ECEC.

2. Research Field

Intercultural education was launched by UNESCO and the Council of Europe in the 1970s and 1980s, and

Hill (

2020, p. 12, our translation), inspired by Lorentz 2013 writes that: “intercultural teaching has been seen to work for mutual exchange and understanding between cultures and thus as an opportunity to deal with problems such as racism, segregation, and discrimination”. An intercultural and interreligious competence such as the one described in the previous section has thus been argued for as being of critical importance for developing ECEC teacher professionalism and, therefore, for what is taught in Swedish PTEs. The importance of adequate preschool teacher education is also highlighted in ECEC studies of preschool teachers’ competence in meeting children and families from different backgrounds (

Stier et al. 2012) and in handling the celebration of different traditions and passing on and developing a cultural heritage (

Puskás and Andersson 2017;

Reimers 2019;

Reimers and Puskás 2022). The results of these studies implicate that Swedish PTEs fail to provide the students with the necessary means to meet the demands for professionally and confidently providing socially sustainable and interculturally aware teaching and caring stated in the curriculum for the preschool (

SNAE 2018).

Apart from the study presented in this article, no studies have been conducted on a national scale explicitly focused on religion and worldviews in Swedish PTEs. However, research in related areas such as intercultural competence and diversity discourses in PTEs and other teacher programs (e.g.,

Abraham and Margrain 2022;

Bayati 2014;

Rosén and Wedin 2018;

Stier and Sandström 2018) are of relevance here. For example,

Abraham and Margrain (

2022) show that intercultural practice is a concern connected to professional preschool teacher practice that is asked for by students themselves during their education. Both national and international studies of PTEs and other teacher programs (e.g.,

Bayati 2014;

Layne and Dervin 2016;

Rosén and Wedin 2018) show problematic “othering” and excluding discourses related to ethnicity within the education studied, which underline the need pointed out by

Rissanen et al. (

2016) and

Licardo and Leite (

2022) to create safe spaces to support students’ self-reflection and discussion.

Rosén and Wedin’s (

2018) study shows how students in PTEs position themselves and are positioned by others within diversity discourses, where certain students are positioned as “the others”. Based on their minority position, students are also expected to add value to pre-service education and reproduce a discourse of diversity as a positive asset in education. At the same time, they are expected to perform similarly to everyone else in the program. Similar results are shown by

Bayati (

2014) in teacher education, where she exemplifies how students within teacher education handle discourses about the racialized “other” in their everyday educational practices. There are also scholars such as

Poulter et al. (

2016) that problematize a simplified use of the concept of religion multicultural or intercultural education and its liberal secularist foundations, highlighting that when “religion is defined in binary opposition to secular, religion is equated with the private, irrational, violent, anti-democratic ‘Other’ in the modern, scientific discourse” (

Poulter et al. 2016, p. 73).

Returning to the issue of educating preschool student teachers in intercultural and interreligious competencies, this has been examined to a higher degree in international research on teacher professionalism in higher education (See

Rissanen et al. 2016,

2020;

Kuusisto 2017) than in Swedish research. For example,

Rissanen et al. (

2016) and

Licardo and Leite (

2022), based on their results, point to a need for teacher educators to be able to teach accurate knowledge content and show that using relevant teaching materials and experiences is considered helpful for PT students to gain intercultural competence. In a Swedish context, both

Bayati (

2014) and

Stier and Sandström (

2018), based on their results, argue that preschool teacher educators need to work more systematically with intercultural pedagogy and intercultural communication and to increase discursive awareness.

There is also relevant previous research in the ECEC that shows children’s well-being and sense of belonging to be key aspects of social sustainability (

Boldermo and Ødegaard 2019;

Johansson and Rosell 2021). In addition, equitable and meaningful relations towards different cultures can be understood as some of the key questions of how to live sustainably (

Wals 2017). Based on a holistic view of the child and an intercultural norm critical ethics of care,

Raivio et al. (

2022) also argue for the importance of the preschool teacher’s sensitivity towards the child’s worldview with its spiritual, religious, ethical, or existential aspects. These knowledges and abilities are to be regarded as part of the preschool teacher’s caring mission for children’s well-being and sense of belonging in the short run and in the long run for social sustainability.

3. Theoretical Underpinnings

The study’s overarching theoretical perspective is based on a feminist and post-colonial point of view. We are inspired by

Hooks’ (

2003) writings on what she calls a ‘beloved community’ when we use the concept of ‘caring communities’ or ‘sustainable communities of care’ (

Raivio et al. 2022). In addition, the concept of ‘caring communities’ is also inspired by

Noddings’ (

2013) care ethics, which is based on a relational approach, and

Yuval-Davis’s (

2011) political concept of ‘belonging’, which she defines as an emotional attachment and feelings of belonging, or “feeling ‘at home’” (

Yuval-Davis 2006, p. 197). A caring community is, based on these influences, characterized by both the teachers’ sensibility to the students’ expressions of their personal experiences and worldviews and of critical awareness and self-reflectiveness based on their social position. This adds a norm-critical and power-conscious dimension (e.g.,

Kumashiro 2000) to both the role of the teacher and the pedagogical aim of PTEs. The concepts ‘marginalization’, ‘exclusion’, and ‘othering’ used by post-colonial thinkers such as

Spivak (

[1987] 2006) and

Powell (

2012) point out some of the consequences of not providing this kind of community in education. All of the above are essential components in the model used in the analysis outlined in the following paragraph.

3.1. A Theoretical and Analytical Tool

To investigate Swedish PTEs on a national policy level, some aspects of a model that works as a theoretical and analytical tool for understanding, researching, and planning socially sustainable communities of care (cf.

Raivio et al. 2022) are used. The model originally consisted of six dimensions of care: international, societal (national), community, situational, event, and act. The six dimensions are to be seen as flexible and influencing each other. The model is here used for understanding content and discursive norms regarding religion and worldviews in the PTEs’ curricula, related to the societal (national) and community dimension, and in some respect, even the international dimension with, for example, the global policies for education such as the Agenda 2030 (

UN 2015). The societal dimension encompasses the national discourse on religion and worldviews as well as the formal laws and ordinations regulating the PTEs. The community dimension, referred to as a potentially socially sustainable community of care, is defined as the local PTEs, including the formal local policies (such as the curricula and other kinds of local policy documents) and their content, as well as the local discursive norms, which in turn, regulate the content and contributes in reproducing discursive norms within the classrooms of specific PTEs. The troublesome othering, excluding, or marginalizing discursive norms highlighted by post-colonial and feminist scholars (e.g.,

Hooks 2003;

Powell 2012;

Spivak [1987] 2006) is seen as part of the informal social and cultural incentives preeminent in all the dimensions.

It is, thus, based on this model, in the respective local communities (PTEs), that incentives for the PTE teachers to produce a caring education and teaching are studied, and in this case, the local curricula for the PTE programs have been the focus of analysis. However, these curricula cannot be understood without being read in the light of policies in the international and societal/national dimensions, since when it comes to issues of justice, social sustainability, equality, and gender equality, it is in the respective country’s governing documents that formulations of global agreements are implemented. A curriculum formulated in the community dimension is according to the theoretical and analytical model we use, also to be seen as influencing the situational, event, and act dimensions, where education is put into practice.

3.2. Methodological and Ethical Considerations

Informed by Critical Discourse Analysis [CDA] (

Fairclough 2010;

Wodak and Meyer 2001), the methodological approach focuses on a social issue in higher education, namely, the issue of inclusion and exclusion concerning religions and worldviews. It also includes a search for incentives for teacher educators to contribute to PTE students’ development of socially sustainable professionalism and to make Swedish PTEs into socially sustainable and caring educational environments (

Raivio et al. 2022) where the students can experience a sense of belonging (

Yuval-Davis 2011). Departing from this, and in line with the theoretical and analytical tool used, the semiotic dimension of the social issue studied, represented by policy texts, is in this methodological setting understood as one element of social life, interconnected with many other elements.

The sources used were official documents published online, and no personal or sensitive information was handled in the study. Still, a research ethics stance has been used throughout the study. Situating ourselves from a feminist and post-colonial intersectional understanding of power relations (e.g.,

Crenshaw 1991;

Hooks 2003;

Powell 2012;

Spivak [1987] 2006) where, for example, gender, ethnicity, skin color, worldview, and occupation are understood as mutually influencing social categories, there is a need for an awareness of one’s position in research (

Letherby 2003). In our particular case, we, the three scholars, are all white Western women from two Nordic countries. All three, besides being scholars, also teach in different (Swedish and Finnish) PTEs and thus have a double perspective on and interest in the results of the study. Two of us have also been practicing as preschool teachers. This puts us as scholars in a specific asymmetric position of power compared with many of the teachers and students who are possibly affected by our results, but it also gives us a unique insight into the daily lives of teacher educators.

4. Results

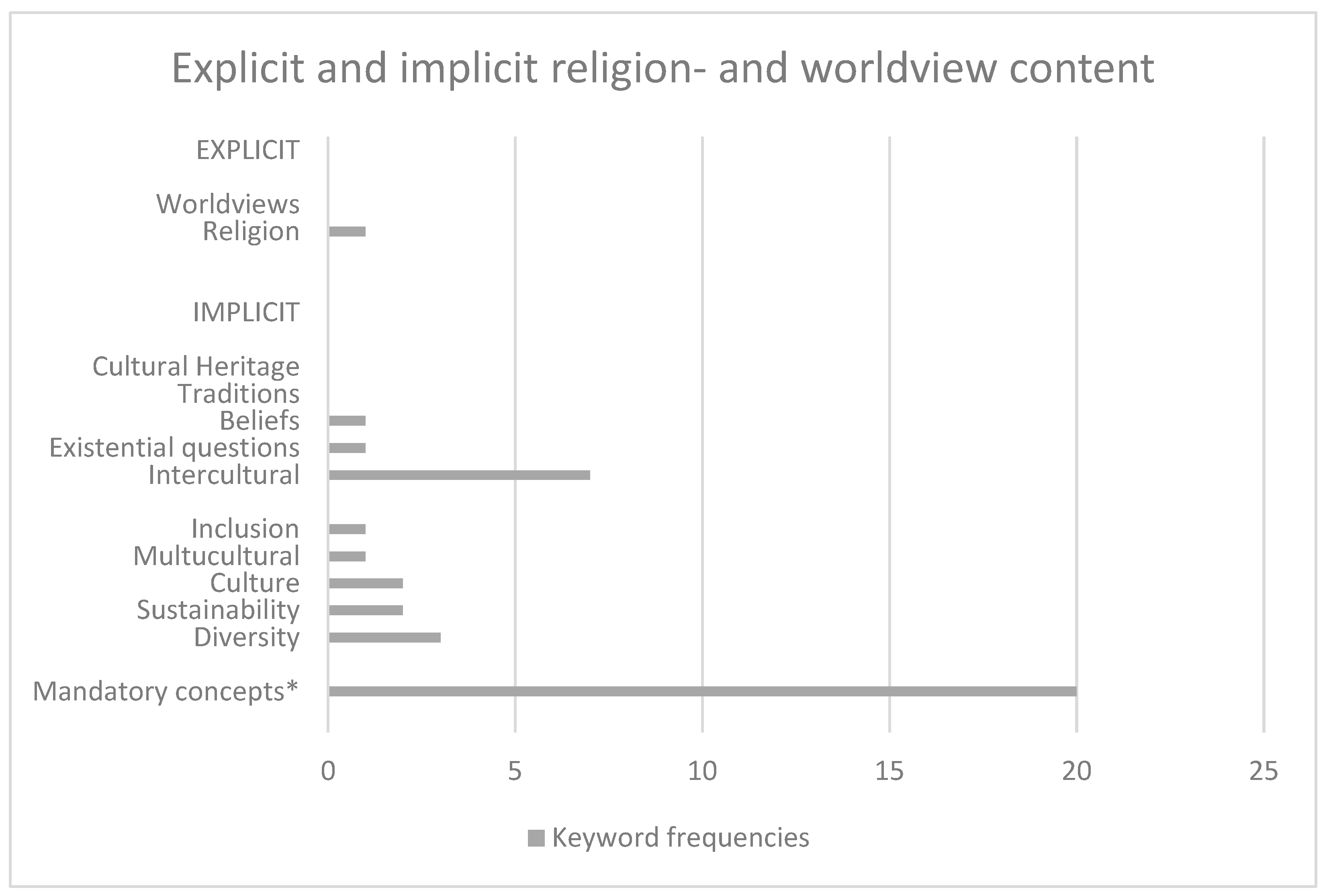

As shown in

Figure 1 below, all twenty PTE curricula have used the same mandatory concepts from the HEO (

SCS 1993), which enables conditions for content-wise equivalence in all education in the country.

As an example, all the programs include the statements from the HEO (

SCS 1993), saying that the students after the preschool teacher’s degree must demonstrate the ability to: “communicate and anchor the value base of the preschool, including human rights and the basic democratic values”. In addition, a majority of the curricula in this study also include wordings from the HEO about the students being able to show the ability to prevent and counteract discrimination and other abusive treatment of children, show an ability to consider, communicate and anchor a gender equality and equality perspective in the educational activities (

SCS 1993). Even though this is because these phrases are mandatory, they still, together with the examples of mentionings of for example ‘culture’, ‘diversity’, ‘existential questions’, and ‘intercultural’, contribute to the implicit incitements for including aspects related to religion and worldviews in the programs’ teaching. Hence, the analysis of the curricula from the twenty Swedish PTEs shows low explicit presence (writings) of religion and worldview content. However, at the same time, there is a possibility for implicit incentives for using pedagogical content related to religion and/or worldviews. However, the lack of explicit expressions of ‘religion’ contributes to reproducing liberal secularist and humanist worldviews as the norm for the PTE. Even though democratic values are highlighted, at the same time, implicitly, it makes ‘religion’ and ‘religious worldviews’ something deviant. In the following section, the content and discursive norms concerning religion and worldviews in the analyzed curricula will be elaborated.

4.1. Low Explicit Presence of Religion

The result shows that only one of the curricula studied mentions ‘religion’ explicitly. In this specific curriculum, ‘religion’ is mentioned on two occasions. The keyword ‘religion’ is evident when the content in the PTE is presented:

The program includes preschool pedagogical and preschool didactic studies within children’s communicative and linguistic development, basic reading, writing and mathematics development, natural science, children’s culture, religion, and community-oriented subjects as well as creative activities.

(Excerpt 1, Curriculum D)

Thus, it becomes evident that when this PTE presents its content, ‘religion’ is explicitly present. Moreover, when the same PTE presents mandatory courses within the program, ‘religion’ is also evident:

Preschool educational and preschool didactic studies comprising 120 higher education credits in children’s communicative and linguistic development, basic reading, writing and mathematics development, natural science, children’s culture, religion, and society-oriented subjects as well as creative activities.

(Excerpt 2, Curriculum D)

The quotations show how ‘religion’ is present when the PTE presents both its content and its mandatory courses. This means that ‘religion’ is not only presented as an important content in this PTE, but it is also a subject that this PTE values in the same way as math, social and natural science, reading, and writing. This result stands out compared to other PTEs in Sweden. Moreover, the keyword ‘worldviews’ was neither mentioned in this nor any of the twenty curricula. The result suggests that in the PTEs community dimension of care (

Raivio et al. 2022), ‘religion’ and ‘worldviews’ are explicitly absent and thus implicitly become something deviant. With the support of the theoretical model, which illustrates how norms and policy texts within the community dimension of care affect what happens within the situational dimension of care, questions arise regarding what can be part of a possible religion and worldview content in the teaching within the PTEs—in the situational dimension of care.

4.2. Possible Implicit Presence of Religion and Worldviews

In several of the PTEs curricula, on the other hand, the mentionings of keywords that implicitly can be interpreted to contain religion and/or worldview content were rather vast. As an exception, the keywords ‘traditions’ and ‘cultural heritage’, which are explicitly mentioned in the curricula for Swedish preschools as important issues in teaching (

SNAE 2018), were not mentioned at all. Variations of the keyword ‘intercultural’ appeared in seven of the twenty curricula (

Figure 1). In one curriculum (curriculum R), this was visible where the education stated its goals:

For a preschool teacher degree at (name of the university), the student must, in addition to objectives specified in the degree scheme—show an understanding of the importance of integrating international, intercultural, and global perspectives in play and learning by placing their studies and their future profession within the Swedish preschool and preschool class in an international and global context.

(Excerpt 3, curriculum R)

In this example, the keyword ‘intercultural’ is connected to global perspectives on play and learning. In the PTEs community dimension of care (

Raivio et al. 2022), the presence of pedagogical content related to ‘religion’ is made possible since the concept of ‘culture’ can be interpreted to include aspects related to ‘religion’ (e.g.,

Raivio and Skaremyr 2022). However, this is not clear in relation to an intercultural perspective on play and learning.

In another curriculum (curriculum T), the keyword ‘intercultural’ is found in the description of an optional course during the PTEs last semester at the advanced level: “

Intercultural Perspectives 1 for preschool teachers” (Excerpt 4, curriculum T, authors’ italicization). While the first example from curriculum R makes visible a PTE that includes intercultural and global perspectives in play and learning in their education for all preschool student teachers, the second curriculum, T, shows the possibility for studies of intercultural perspectives in a more general sense as optional. Just as in Excerpt 3, it is possible to assume that the teaching in this optional course in intercultural perspectives (Excerpt 4) is likely to contain content regarding ‘religion’ and ‘worldviews’ based on the interpretation that pedagogical content on ‘culture’ can also include aspects of religion (

Raivio and Skaremyr 2022).

The mandatory concepts within the implicit category (

Figure 1) found in all the PTE curricula may, even though it is not as obvious, just as the examples of ‘intercultural’, be possible to interpret as opening up for teachings within the PTEs, including aspects of religion and worldviews to be discussed. The teaching within specific PTEs—the situational dimension of care (

Raivio et al. 2022) can thus include religion and worldviews.

4.3. Liberal Secularist and Humanist Democracy as the Foundation for Teaching

However, looking at the whole picture, the focus on intercultural education and the dominating lack of mentioning of ‘religion’ resonates well with what

Poulter et al. (

2016) describe as a liberal secularist foundation, for example, for Nordic intercultural (or multicultural) education. The curricula also show a vast focus on teaching the students democratic values. One conclusion is, therefore, that the discursive norm that arises in the analysis reproduces liberal secular and humanist worldviews as the foundation for educating about democracy in the PTEs—a norm that contributes to perceiving democracy as natural or as common sense and individuals as freely and fully capable of making rational and ethical choices, solving problems through intelligence, scientific methods, and perseverance (cf. e.g., the “secular humanist declaration” by

Kurtz and Kurtz 1980). At the same time, this norm implicitly depicts ‘religion’ as anti-democratic and as something private, irrational, and violent or as the ‘Other’ in a modern scientific discourse (

Poulter et al. 2016). Another conclusion is that at a national policy level, the documents studied do not show explicit policy-related incentives for the PTEs to promote social sustainability regarding providing students with proper knowledge and skills concerning religion and worldviews.

5. Material, Method, and Analysis

The study focused on the PTEs where the education is given in place (not online) and full-time. The material for the study thus consists of policy documents, more specifically the overarching curricula (hence not the curricula for specific courses) of all twenty PTEs in Sweden in 2022, found on the different PTEs websites. The PTEs curricula were first downloaded, and a data matrix was created, where the collected curricula were coded according to the alphabet, with the letters a-t for increased confidentiality. The curricula were then read to obtain an overview of the content. Within most of the curricula, the titles of all courses for the whole education were mentioned, and in some, there were even short course descriptions. To be able to make an interconvertible comparison, the material was supplemented by looking at the course titles and, if available, the course descriptions on the websites of the programs that did not include those in their curricula. However, what we found were mainly descriptions of the programs as a whole and their eventual specific focus.

A discourse analysis (

Fairclough 2010;

MacLure 2003;

Wodak and Meyer 2001) was made, where the selected documents were studied for wording and statements related to religion and worldviews in some way. A combined qualitative approach was used since the meaning of the texts was focused on, but this was combined with a few numerical elements (

Cohen et al. 2018) where the use of significant keywords was counted in the texts to contribute to the analysis related to the research question of to what degree elements related to religion and worldview are represented in the material. The first categorization of the content was made based on whether the keywords ‘religion’ or ‘worldviews’ were used explicitly in the curricula. Within the following process, a color coding of the texts was made based on the wordings’ proximity to religion and worldviews. Based on this, the explicit use of the keywords ‘religion’ and ‘worldview’ was color-coded in magenta. A second categorization was made based on keywords, which could imply an implicit content of religions and worldviews regarded as relevant based on earlier research, such as ‘beliefs’ (In Swedish, ‘uppfattningar’), ‘children’s rights’, ‘culture’, ‘cultural heritage’, ‘democracy’, ‘diversity’, ‘ethics’, ‘equality’, ‘equity’, ‘existential questions’, ‘human rights’, ‘inclusion’, ‘intercultural’, ‘intersectionality’, ‘multicultural’, ‘social relations’, ‘sustainability’, ‘sustainable development’, ‘traditions’, and ‘values’. This category was divided into two subcategories: ‘Beliefs’ and ‘existential questions’, and ‘intercultural’ was based on the higher probability of implying a pedagogical focus on religion and worldviews, hence its proximity to ‘religion’ and ‘worldviews’, coded as green, as a separate category. The rest of the keywords in the implicit category were regarded as somewhat less likely to imply a pedagogical focus on religion or worldviews and coded as yellow. However, a third categorization was then made, including most of the keywords originally coded as yellow, which were found to be used in all curricula as required by the HEO (

SCS 1993); ‘children’s rights’, ‘democracy’, ‘ethics’, ‘equality’, ‘equity’, ‘human rights’, ‘social relations’, ‘sustainable development’, ‘values’. These were de-coded as turquoise. The surrounding text where each keyword was found was copied and pasted into the matrix so that the textual context could be taken into account.

The relevant text excerpts from the documents where explicit or implicit content on religion and worldviews were found were then further analyzed qualitatively using the theoretical and analytical tools (

Raivio et al. 2022) outlined above. That is, a feminist and post-colonial perspective was applied to the discursive content by using the analytical question: What discursive subjects are created, and what or who is constructed as “the other”, marginalized or made invisible in the curricula, related to a national societal and local community dimension?