Codex and Contest: What an Early Christian Manuscript Reveals about Social Identity Formation Amid Persecution and Competing Christianities †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| Text | Scribal Hand | Pagination |

|---|---|---|

| Section 1 | ||

| The Protoevangelium of James (Nativity of Mary) | A | 1–49 |

| Correspondence between Paul and the Corinthians | B | 50–57 |

| 11th Ode of Solomon | B | 57–62 |

| Jude | B | 62–68 |

| Melito’s homily on the passion | A | 1–63 |

| Hymn fragment | A | 64 |

| Section 2 | ||

| Apology of Phileas | C | 129–146?6 |

| Psalms 33–34 (LXX) | D | 147–151?7 |

| Section 3 | ||

| 1–2 Peter | B | 1–36 |

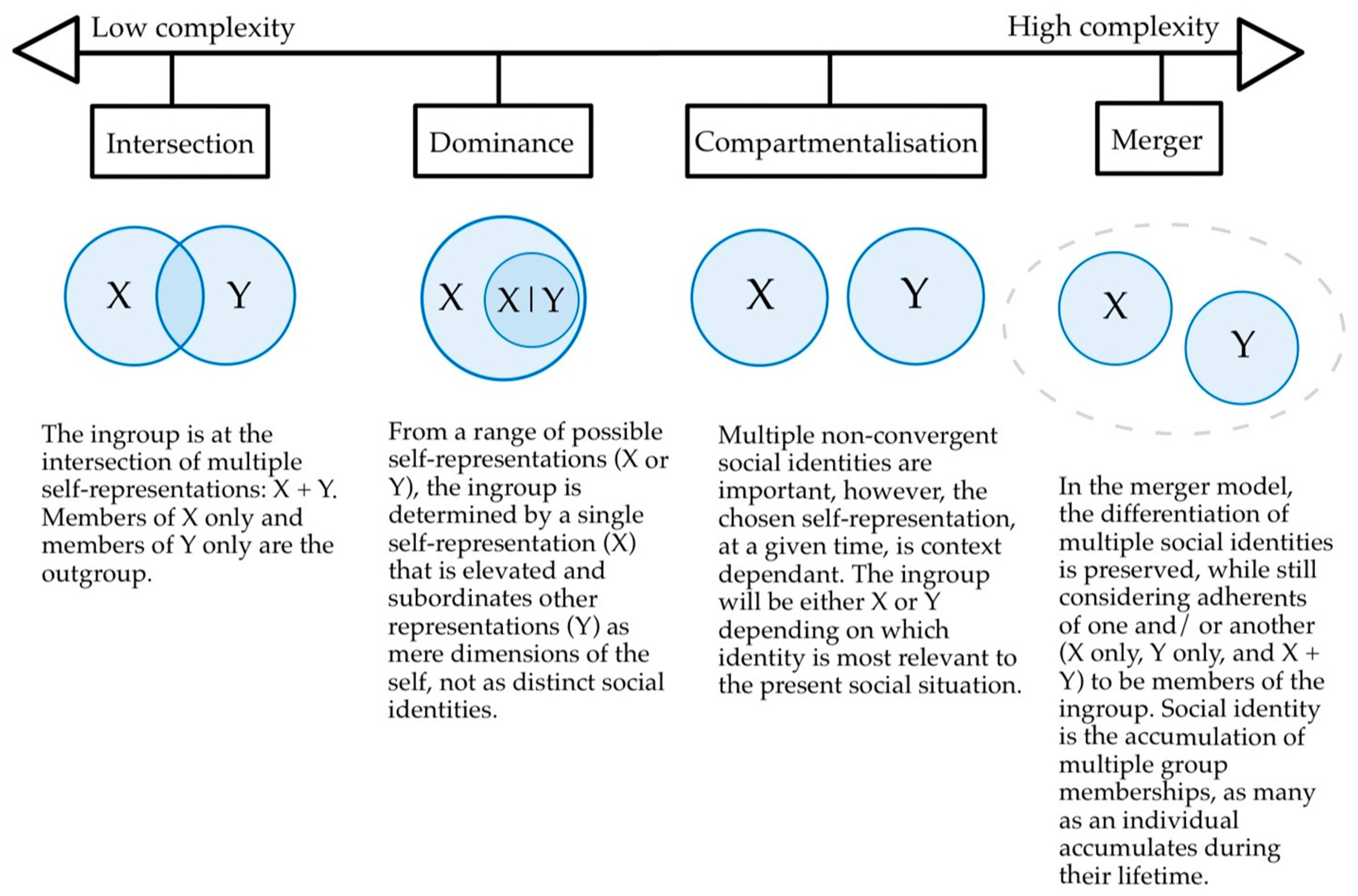

2. Social Identity Theory and Social Identity Complexity Theory

3. Who Owned and Used the BMC?

“Le terme même de communauté n’est-il pas abusif en sous-entendant un profil homogène pour l’ensemble de ses utilisateurs? De plus, nous avons vu que cette bibliothèque s’est constituée sur trois siècles et qu’elle était donc susceptible d’être l’agrégat de plusieurs fonds d’origines diverses qui ne reflètent pas nécessairement l’état d’esprit de l’ensemble des usagers à la fin de son histoire. Enfin, elle peut avoir donné lieu à plusieurs activités, qui ne sont pas exclusives l’une de l’autre: création, lecture édifiante et instruction scolaire. Autrement dit, l’hypothèse d’une bibliothèque d’école n’est pas incompatible avec un milieu religieux”.

“the differing qualities of execution show that, in most cases, the producers of these manuscripts were not professional scribes but individuals whose writing abilities varied and who were producing books intended for practical use, by other individuals or groups, in daily life”.

4. The Socio-Historical Situation: Persecution and Competing Christianities

5. Marginalia and Textual Emendations

6. The BMC and Social Identity Complexity

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The circumstances of its discovery, along with the other Bodmer Papyri in the same cache, are shrouded in a fair bit of mystery, which some have attempted to decipher (Robinson 2011; Nongbri 2018a, pp. 189–238). For the purposes of this paper, we accept that the exact site of the find is inconclusive but still locate it somewhere between Panopolis (present-day Akhmim) and Thebes (present-day Luxor), including the specific area of Dishna. |

| 2 | The scribal idiosyncrasies of P72 (Jude and 1–2 Peter in the BMC), most notably the scribe’s difficulty in spelling (affirming that a Coptic individual attempted to transcribe in Greek), have further substantiated private use (Haines-Eitzen 2000, p. 73; Wasserman 2005, p. 154; Royse 2008, p. 582). |

| 3 | For basic details of the codex and a list of major publications, see Trismegistos (n.d.). For access to high-resolution images of each of these texts, see Digivatlib (n.d.) for 1–2 Peter and Bodmer Lab (n.d.) for the rest. See the reference list below for further publications related to the study of the BMC and the Bodmer Papyri. |

| 4 | See Clarke and Tucker (2014, pp. 67–91). They write, “What is the use of social theory to historians, and what is the use of history to social theorists? For historians, social theory provides a framework for interpreting the evidence, and for theoreticians, social history provides the evidence needed to substantiate their purported theoretical claims” (Clarke and Tucker 2014, p. 82). This outcome is, however, impacted by limited access to historical data (Clarke and Tucker 2014, p. 67). Horrell (2009, p. 17) disagrees with the sharply drawn distinction between social history and social science (theory). His disagreement is a resistance to the “insistence on the use of models as the only proper and recognisably social-scientific method” (Horrell 2009, p. 11). He advocates for the use of eclectic theoretical “approaches” as legitimate ways to study the NT writings and their depicted social worlds (Horrell 2009, pp. 12–20). |

| 5 | The table I have supplied was adapted from Haines-Eitzen (2000, p. 97) and Wasserman (2005, p. 140), who both adapted it from Testuz (1959a, p. 8). We note that Orsini (2019, pp. 38–39) identifies a different scribal hand for Melito’s homily and the hymn fragment (both datable to the 4th century) to the one that penned the Protoevangelium of James. This brings the number of scribes to five as opposed to the four in Testuz’ assessment. Since the BMC was disassembled and the individual texts published separately from each other, some level of conjectural reconstruction is required. Consequently, what Testuz proposed was hypothetical, and not all scholars agree with his reconstruction. For example, based on the results of his study, Wasserman (2005, p. 145) is inclined to believe that, in its final state, Section 3 followed immediately after Section 1, meaning that Section 2 either began or ended the codex. Such a structure of the BMC would allow for Jude and 1–2 Peter, works considered to be copied by the same scribe (Orsini 2019, p. 43), to be placed in the same codicological section. However, Nongbri (2016, p. 410) believes that the codicological connection between Jude and 1–2 Peter is incidental; prior to their inclusion in the BMC, they were originally part of distinct collections. There is also disagreement about whether certain writings belong in the codex or not. Nongbri (2018b) argues, on the basis of various material features (page shape, lack of evidence for binding holes, unique pagination sequence, and different scribal hands), that Phileas’ Apology and the Psalms were probably never part of the BMC. In our estimation, Nongbri’s observations are compelling; however, considering that the Apology and the Psalms share key theological motifs with other texts of the codex, we are inclined to believe that both were, in some way, part of the codex (not physically stitched but inserted, perhaps in haste, to be bound at a later stage?). How exactly will probably always remain a matter of conjecture. |

| 6 | The Apology is highly fragmentary, with the result that the page numbers are not clear, requiring the pagination to be reconstructed. |

| 7 | The top margins of the Psalms are mostly missing, requiring pagination to be reconstructed. Wasserman (2005, p. 140) tentatively has the Psalms ending on p. 151, while Nongbri (2018b) ends the sequence on p. 150. |

| 8 | For specific examples, see contributions by Vearncombe (2020, pp. 53–54), Williams (2020, p. 164), Choi (2020, pp. 186–87), Crook and Stansell (2020, p. 206), Neufeld and Crook (2020, p. 236), and Elliot (2020, p. 246). |

| 9 | For more on the origins of SIT, see Hogg (2006, pp. 111–36), Esler (2014, pp. 29–65), and Russell (2020, pp. 1–24). |

| 10 | Much of Tajfel’s work with social identity was grounded in the ‘minimal group experiments’. See Tajfel (1970, pp. 96–103), Tajfel et al. (1971, pp. 149–78), and Billig and Tajfel (1973, pp. 27–51). |

| 11 | Hogg (2006, p. 120), however, offers a significant caveat: “Self-enhancement is undeniably involved in social identity processes. However, the link between individual self-esteem and positive group distinctiveness is not always that tight. Although having a devalued or stigmatized social identity can depress self-esteem, people are exceedingly adept at buffering themselves from the self-evaluative consequences of stigma”. Hogg (2006, p. 121) goes on to say that people may be motivated toward “optimal distinctiveness”, seeking to be distinct but not too distinct. |

| 12 | © [Author]. Adapted from Roccas and Brewer (2002, pp. 90–91). |

| 13 | From our perspective, “ownership” includes production; those who produced the BMC also owned it. |

| 14 | For proposed inventories of the collection, see Miguélez-Cavero (2008, pp. 218–21), Robinson (2011, pp. 169–72), Fournet (2015, pp. 21–23), and Nongbri (2018a, p. 217). |

| 15 | Rousseau (1985, p. 19) writes, “Pachomius and his associates were markedly attached to orthodoxy”; however, he also acknowledges that some gnostic influence may have been retained (Rousseau 1985, p. 22). Brakke (1998, pp. 111–12, 116) argues that Pachomius was simultaneously in step with emerging orthodoxy while retaining autonomy within the order. Orthodox Pachomian monasticism came into full fruition only under Theodore, one of Pachomius’ successors, and beyond (Brakke 1998, p. 112). For more on Pachomius, see Goehring (2017, pp. 1021–35). For a daring proposition that suggests that the Bodmer Papyri (also known as the Dishna Papers) and the Nag Hammadi codices could have been owned and used by Pachomian monks, see Lundhaug (2020, pp. 329–86). For criticisms to such a thesis, see Lewis and Blount (2014, pp. 399–419) and Piwowarczyk and Wipszycka (2017, pp. 432–58). |

| 16 | See note 14. |

| 17 | While these comments are in the context of a discussion about the authorship of the Gospels (see esp. Walsh 2021, pp. 131–33), they are applicable to the Bodmer Papyri and the BMC. The central argument in Walsh’s book is that Synoptic Gospels are not extraordinary religious texts that were products of theologically coherent communities; rather, they are typical and bear resemblance to other Greco-Roman literature of the imperial period (Walsh 2021, pp. 4–15). |

| 18 | For more on how early Christian manuscripts, like the BMC, functioned as “social mediators”, see Knust (2017, pp. 99–118). |

| 19 | Horrell connects official and non-official public persecution in the following way: “To depict these as two alternatives does not rightly appreciate the legal status of Christianity in the first three centuries, nor the connections between public hostility and the accusatorial process, which remained the route through which Christians generally came to judicial attention… The occasional and local nature of Christian persecution does not mean that there was no official stance towards Christianity, but is in fact reflective precisely of that stance” (Horrell 2013, p. 197). |

| 20 | For philosophical opposition to early Christianity, see Simmons (2017, pp. 796–816). |

| 21 | The use of the term “withdrawal” does not denote a physical withdrawal that would be typical of sectarian seclusion. As Miroslav Volf (1994) has shown, the writer of 1 Peter was concerned with exhorting his readers to display a “soft difference”, socially distancing themselves from practices that were considered anathema to Christianity while, simultaneously, working to maintain societal stability (cf. 1 Peter 4:3–4; 2:11–3:9). These Anatolian Christians were to be different to those around them (“αγειοι εσεσθε διοτι εγω αγειος ειμει”; 1:16) but not removed from them. |

| 22 | Unless otherwise stated, we have quoted from the BMC retaining the individual scribe’s spelling, which is oftentimes errant. We have done this because the codex is the primary focus of study. |

| 23 | There is another intriguing reversal that takes place in 1 Peter that has to do with the label Χριστιανός. At 4:16, the author encourages his readers to not be ashamed (μη αἰσχυνέσθω in the Accordance Electronic (n.d.); μη εσχυνεσθω in P72) if they suffer for being Christians. Χριστιανός was not a name that Christians chose for themselves; rather, it was bestowed on them, seemingly by the Roman administration (Horrell 2013, p. 169), and intended as a stigma, a label that marked its wearers as worthy of shame (Horrell 2013, p. 198). However, the author of 1 Peter reinterprets this label as one of honour and one that glorifies God, most especially if the name itself is the cause for their suffering (Horrell 2013, p. 209). In the SIT framework, such reinterpretation would be called ‘social creativity’, which, in the case of 1 Peter, functions as an important authorial strategy that reinterprets an intended negative label and introduces a new superordinate identity. On this, Hunt (2020, p. 541) writes, “Although in their discursive environment, they are denigrated as ‘Christians’, 1 Peter reclaims the term as an ingroup label, and generally engages in the social creativity necessary to raise the status of the believing community”. |

| 24 | Because P. Bodmer XX has many lacunae, some measure of conjecture about its contents is required. I have given the plate numbers for easier reference. For more, see Pietersma (1984, pp. 18–19). See Martin (1964, pp. 24–52) for Greek and Latin versions of the Apology. |

| 25 | Testuz’s (1959a, pp. 77–81) transcription has been used for the Psalm references. |

| 26 | Lattke’s (2009, pp. 149–50) translation has been used for the Ode references. See also Testuz (1959b, pp. 61–69) for a Greek transcription and French translation. |

| 27 | For early diversity, see Klutz (2017, pp. 142–68). For Jewish Christianity, see Luomanen (2012), Bird (2017, pp. 84–94), and Broadhead (2017, pp. 121–41). For Gnostics, see Brakke (2010) and Logan (2017, pp. 850–66). |

| 28 | See Zervos (2019) for a recent study on the compositional journey of the Protoevangelium of James. Zervos (2019, p. 20) believes that, at the third stage of its composition, this proto-gospel was redacted to give it a more orthodox flavour. |

| 29 | Testuz’s (1958, pp. 31–126) transcription has been used for the references. This work also contains a French translation, side by side with the Greek. |

| 30 | Hovhanessian (1998, pp. 110–12) translates these as “the wicked”, “falsifiers of his words”, “children of wrath”, and “children of vipers”, respectively. Hovhanessian’s (1998, pp. 109–13) translation has been used for the references. |

| 31 | Testuz’s (1960, pp. 26–153) transcription has been used for the references. This work also contains a French translation, side by side with the Greek. |

| 32 | For a minuscule transcription of P72, see Comfort and Barrett (1999, pp. 470–90). |

| 33 | For a detailed study of the scribal habits of P72, see Royse (2008, pp. 545–614). |

| 34 | Doing so might, however, require a later dating for the texts of P72. |

| 35 | “About a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his possession”. |

| 36 | Horrell (2013, pp. 133–63) offers an extensive analysis of the function of these words in 1 Peter 2:9. Importantly, ethnicity is considered by many to be socially constructed rather than biologically inherent (Horrell 2013, pp. 157–58; Ok 2021, p. 5; Marcar 2022, pp. 1–2). For more on ethnicity in 1 Peter, see Ok (2021) and Marcar (2022). See Skarsaune (2018, pp. 250–64) and Gruen (2018, pp. 235–49) for related discussions about ethnicity and early Christianity. See Horrell (2020, pp. 67–92) for a recent treatment of the language of ethnicity and race. |

| 37 | For the relation of ethnicity and social identity, see Kuecker (2014, pp. 92–116). Horrell (2013, pp. 159–60) draws on Anthony D. Smith’s definition of ethnic groups to show how ‘Peter’ demarcates the new identity of his readers. |

| 38 | ‘Peter’ exhorts his audience to submission in a variety of areas: citizens to political authority (2:13–17), slaves to masters (2:18–25), wives to husbands (3:1–6), and husbands to wives (3:7). |

| 39 | © Reproduced from Kok (2023, p. 121). |

References

- Accordance Electronic, ed. n.d. Novum Testamentum Graece, 28th ed. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft.

- Agosti, Gianfranco. 2015. Poesia Greca nella (e della?) Biblioteca Bodmer. Adamantius 21: 86–97. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzana, Giovanni. 2020. Deviance. In The Ancient Mediterranean Social World: A Sourcebook. Edited by Zeba A. Crook. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 225–35. Available online: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=2621762 (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Beare, Francis W. 1961. The Text of I Peter in Papyrus 72. Journal of Biblical Literature 80: 253–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billig, Michael, and Henri Tajfel. 1973. Social Categorization and Similarity in Intergroup Behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology 3: 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, Michael F. 2017. Jesus the Eternal Son: Answering Adoptionist Christology. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. Available online: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/lib/pretoria-ebooks/detail.action?docID=5975098 (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Bodmer Lab. n.d. Available online: https://bodmerlab.unige.ch/constellations/papyri/barcode/1072205366 (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Brakke, David. 1998. Athanasius and Asceticism. Edited by Johns Hopkins Paperbacks. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brakke, David. 2010. The Gnostics: Myth, Ritual, and Diversity in Early Christianity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead, Edwin K. 2017. Early Jewish Christianity. In The Early Christian World, 2nd ed. Edited by Philip F. Esler. Routledge Worlds. London: Routledge, pp. 121–41. Available online: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/lib/pretoria-ebooks/reader.action?docID=4921825&ppg=152 (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Camplani, Alberto. 2015. Per un Profilo Storico-religioso degli Ambienti di Produzione e Fruizione dei Papyri Bodmer: Contaminazione dei Linguaggi e Dialettica delle Idee nel Contesto del Dibattito su Dualismo e Origenismo. Adamantius 21: 98–135. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Agnes. 2020. Healing. In The Ancient Mediterranean Social World: A Sourcebook. Edited by Zeba A. Crook. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 224–41. Available online: https://www1.up.ac.za/uplogin/faces/login.jspx?bmctx=021843C5099ED188C20F16CEC40FB9E3&contextType=external&username=string&password=secure_string&challenge_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww1.up.ac.za%2Fuplogin%2Ffaces%2Flogin.jspx&request_id=5822217524497874521&authn_try_count=0&locale=en_US&resource_url=%252Fuser%252Floginsso (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Clarke, Andrew D., and J. Brian Tucker. 2014. Social History and Social Theory in the Study of Social Identity. In T&T Clark Handbook to Social Identity in the New Testament. Edited by J. Brian Tucker and Coleman A. Baker. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 67–91. [Google Scholar]

- Comfort, Philip W., and David P. Barrett, eds. 1999. The Complete Text of the Earliest New Testament Manuscripts. Grand Rapids: Baker Books. [Google Scholar]

- Crook, Zeba A., ed. 2020. The Ancient Mediterranean Social World: A Sourcebook. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. Available online: https://login.uplib.idm.oclc.org/login?qurl=https://search.ebscohost.com%2flogin.aspx%3fdirect%3dtrue%26db%3dnlebk%26AN%3d2621762%26site%3dehost-live%26scope%3dsite (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Crook, Zeba A., and Gary Stansell. 2020. Friendship and Gifts. In The Ancient Mediterranean Social World: A Sourcebook. Edited by Zeba A. Crook. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 258–72. Available online: https://search-ebscohost-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=2621762&site=ehost-live&scope=site&ebv=EK&ppid=Page-__-211 (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- De Vos, Craig. 2017. Popular Graeco-Roman Responses to Christianity. In The Early Christian World, 2nd ed. Edited by Philip F. Esler. Routledge Worlds. London: Routledge, pp. 817–34. Available online: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/lib/pretoria-ebooks/reader.action?docID=4921825&ppg=848 (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Digivatlib. n.d. Available online: https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Pap.Bodmer.VIII/0001 (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Duling, Dennis C., and Richard Rohrbaugh. 2020. Collectivism. In The Ancient Mediterranean Social World: A Sourcebook. Edited by Zeba A. Crook. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 95–106. Available online: https://search-ebscohost-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=2621762&site=ehost-live&scope=site&ebv=EK&ppid=Page-__-95 (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Ehrman, Bart D. 1996. The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effect of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament. New York: Oxford University Press. Available online: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/lib/pretoria-ebooks/detail.action?docID=694001 (accessed on 27 February 2022).

- Elliot, John H. 2020. Evil Eye. In The Ancient Mediterranean Social World: A Sourcebook. Edited by Zeba A. Crook. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 321–33. Available online: https://search-ebscohost-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=2621762&site=ehost-live&scope=site&ebv=EK&ppid=Page-__-246 (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Esler, Philip F. 1994. The First Christians in Their Social Worlds: Social-scientific Approaches to New Testament Interpretation. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Esler, Philip F. 2014. An Outline of Social Identity Theory. In T&T Clark Handbook to Social Identity in the New Testament. Edited by J. Brian Tucker and Coleman A. Baker. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 29–65. [Google Scholar]

- Fournet, Jean-Luc. 2015. Anatomie d’une Bibliothèque de l’Antiquité tardive: l’Inventaire, le Faciès et la Provenance de la ‘Bibliothèque Bodmer’. Adamantius 21: 8–40. [Google Scholar]

- Goehring, James E. 2017. Pachomius the Great. In The Early Christian World, 2nd ed. Edited by Philip F. Esler. Routledge Worlds. London: Routledge, pp. 1021–35. Available online: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/lib/pretoria-ebooks/reader.action?docID=4921825&ppg=1052 (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Gruen, Erich S. 2018. Christians as a “Third Race”: Is Ethnicity at Issue? In Christianity in the Second Century, 1st ed. Edited by James C. Paget and Judith Lieu. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 235–49. [Google Scholar]

- Haines-Eitzen, Kim. 2000. Guardians of Letters: Literacy, Power, and the Transmitters of Early Christian Literature. Cary: Oxford University Press. Available online: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/lib/pretoria-ebooks/detail.action?docID=281053 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Hogg, Michael A. 2006. Social Identity Theory. In Contemporary Social Psychological Theories. Edited by Peter J. Burke. Redwood City: Stanford University Press, pp. 111–36. [Google Scholar]

- Horrell, David G. 2009. Whither Social-scientific Approaches to New Testament Interpretation? Reflections on Contested Methodologies and the Future. In After the First Urban Christians: The Social-scientific Study of Pauline Christianity Twenty-five Years Later. Edited by Todd D. Still and David G. Horrell. London: Continuum, pp. 6–20. [Google Scholar]

- Horrell, David G. 2013. Becoming Christian: Essays on 1 Peter and the Making of Christian Identity. Early Christianity in Context 394. London and New York: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Horrell, David G. 2020. Ethnicity and Inclusion: Religion, Race, and Whiteness in Constructions of Jewish and Christian Identities. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Hovhanessian, Vahan A. 1998. Third Corinthians: Reclaiming Paul for Christian Orthodoxy. Ph.D. thesis, Fordham University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner, Sabine R. 2019. Papyri and the Social World of the New Testament, 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, Laura J. 2020. 1 Peter. In T&T Clark Social Identity Commentary on the New Testament. Edited by J. Brian Tucker and Aaron Kuecker. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 527–47. Available online: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/lib/pretoria-ebooks/reader.action?docID=5993973&ppg=544 (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- King, Marchant A. 1964. Notes on the Bodmer Manuscript: Jude and 1 and 2 Peter. Bibliotheca Sacra 121: 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Klutz, Todd. 2017. From Hellenists to Marcion: Early Gentile Christianity. In The Early Christian World, 2nd ed. Edited by Philip F. Esler. Routledge Worlds. London: Routledge, pp. 142–68. Available online: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/lib/pretoria-ebooks/reader.action?docID=4921825&ppg=173 (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Knust, Jennifer. 2017. Miscellany Manuscripts and the Christian Canonical Imaginary. Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 13: 99–118. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44898621 (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Kok, Jacobus. 2014. Social Identity Complexity Theory as Heuristic Tool in New Testament Studies. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 70: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, Jacobus. 2023. The Dynamics of Exclusion and Inclusion in 1 Peter. In Religiously Exclusive, Socially Inclusive? A Religious Response. Edited by Bernhard Reitsma and Erika van Nes-Visscher. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 115–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kok, Jacobus, and Dieter T. Roth. 2014. Introduction: Sensitivity Towards Outsiders and the Dynamic Relationship Between Mission and Ethics/Ethos. In Sensitivity Towards Outsiders: Exploring the Dynamic Relationship Between Mission and Ethics in the New Testament and Early Christianity. Edited by Jacobus Kok, Tobias Nicklas, Dieter T. Roth and Christopher M. Hays. WUNT 2.364. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kuecker, Aaron. 2014. Ethnicity and Social Identity. In T&T Clark Handbook to Social Identity in the New Testament. Edited by J. Brian Tucker and Coleman A. Baker. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 92–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lattke, Michael. 2009. Odes of Solomon: A Commentary. Translated by Marianne Ehrhardt. Edited by Harold W. Attridge. Hermeneia—A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Nicola D., and Justine A. Blount. 2014. Rethinking the Origins of the Nag Hammadi Codices. Journal of Biblical Literature 133: 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, Alastair H. B. 2017. Gnosticism. In The Early Christian World, 2nd ed. Edited by Philip F. Esler. Routledge Worlds. London: Routledge, pp. 850–66. Available online: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/lib/pretoria-ebooks/reader.action?docID=4921825&ppg=881 (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Lundhaug, Hugo. 2020. The Dishna Papers and the Nag Hammadi Codices: The Remains of a Single Monastic Library? In The Nag Hammadi Codices and Late Antique Egypt. Edited by Hugo Lundhaug and Lance Jenott. Studies and Texts in Antiquity and Christianity 110. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 329–86. [Google Scholar]

- Luomanen, Petri. 2012. Recovering Jewish-Christian Sects and Gospels. Vigiliae Christianae. Supplements Series 110 (1); Leiden: Brill. Available online: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/lib/pretoria-ebooks/detail.action?docID=1010572 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Malina, Bruce J. 2001. The New Testament World: Insights From Cultural Anthropology, 3rd ed. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. Available online: https://archive.org/details/newtestamentworl0000mali_c2v7/mode/2up (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Marcar, Katie. 2022. Divine Regeneration and Ethnic Identity in 1 Peter: Mapping Metaphors of Family, Race, and Nation. SNTS Monograph Series 180; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Victor. 1964. Papyrus Bodmer XX: Apologie de Philéas, Évêque de Thmouis. Cologny-Genéve: Bibliotheca Bodmeriana. Available online: https://archive.org/details/papyrusbodmerxxa0000phil/mode/2up (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Merkt, Andreas. 2015. 1 Petrus: Teilband 1. Novum Testamentum Patristicum 21.1. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Miguélez-Cavero, Laura. 2008. Poems in Context: Greek Poetry in the Egyptian Thebaid 200–600 AD. Studies in the Recovery of Ancient Texts. Sozomena Series 2.1; Berlin: De Gruyter. Available online: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/lib/pretoria-ebooks/detail.action?docID=370769 (accessed on 18 June 2022).

- Moss, Candida R. 2017. Political Oppression and Martyrdom. In The Early Christian World, 2nd ed. Edited by Philip F. Esler. Routledge Worlds. London: Routledge, pp. 783–95. Available online: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/lib/pretoria-ebooks/reader.action?docID=4921825&ppg=814 (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Neufeld, Dietmar, and Zeba A. Crook. 2020. Mockery and Secrecy. In The Ancient Mediterranean Social World: A Sourcebook. Edited by Zeba A. Crook. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 306–20. Available online: https://search-ebscohost-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=2621762&site=ehost-live&scope=site&ebv=EK&ppid=Page-__-236 (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Nicklas, Tobias, and Tommy Wasserman. 2006. Theologische linien im Codex Bodmer Miscellani? In New Testament Manuscripts: Their Texts and Their World. Edited by Thomas J. Kraus and Tobias Nicklas. Texts and Editions for New Testament Study 2. Leiden: Brill, pp. 161–88. Available online: https://search-ebscohost-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=232433&site=ehost-live&scope=site&ebv=EB&ppid=pp_161 (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Nongbri, Brent. 2016. The Construction of P.Bodmer VIII and the Bodmer “Composite” or “Miscellaneous” Codex. Novum Testamentum 58: 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nongbri, Brent. 2018a. God’s Library: The Archaeology of the Earliest Christian Manuscripts. New Haven: Yale University Press, Available on Kindle. [Google Scholar]

- Nongbri, Brent. 2018b. P.Bodmer XX+IX and the Bodmer Composite Codex. Available online: https://brentnongbri.com/2018/03/31/p-bodmer-xxix-and-the-bodmer-composite-codex/ (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Ok, Janette H. 2021. Constructing Ethnic Identity in 1 Peter: Who You Are No Longer. Library of New Testament Studies 645. London: T&T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Orsini, Pasquale. 2019. Studies on Greek and Coptic Majuscule Scripts and Books. Translated by Stephen Parkin, and Laura Nuvoloni. Studies in Manuscript Cultures 15. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Pietersma, Albert. 1984. The Acts of Phileas, Bishop of Thmuis (Including Fragments of the Greek Psalter): P. Chester Beatty XV (With a New Edition of P. Bodmer XX, and Halkin’s Latin Acta). Cahiers d’Orientalisme 7. Genève: P. Cramer. Available online: https://archive.org/details/actsofphileasbis0000unse/mode/2up (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Piwowarczyk, Przemysław, and Ewa Wipszycka. 2017. A Monastic Origin of the Nag Hammadi Codices? Adamantius 23: 432–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pliny the Younger. 2006. Complete Letters. Translated by Patrick G. Walsh. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: OUP Oxford. Available online: https://search-ebscohost-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=271143&site=ehost-live&scope=site&ebv=EB&ppid=pp_278 (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Robinson, James M. 2011. The Story of the Bodmer Papyri: From the First Monastery’s Library in Upper Egypt to Geneva and Dublin. Oregon: Cascade Books, Available on Kindle. [Google Scholar]

- Roccas, Sonia, and Marilynn B. Brewer. 2002. Social Identity Complexity. Personality and Social Psychology Review 6: 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrbaugh, Richard L. 2020. Honor. In The Ancient Mediterranean Social World: A Sourcebook. Edited by Zeba A. Crook. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 74–84. Available online: https://search-ebscohost-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=2621762&site=ehost-live&scope=site&ebv=EK&ppid=Page-__-74 (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Rousseau, Philip. 1985. Pachomius: The Making of a Community in Fourth-Century Egypt. The Transformation of the Classical Heritage 6. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Royse, James R. 2008. Scribal Habits in Early Greek New Testament Papyri. New Testament Tools, Studies and Documents 36. Leiden: Brill. Available online: https://search-ebscohost-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=252986&site=ehost-live&scope=site&ebv=EB&ppid=pp_545 (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Russell, A. Sue. 2020. A Genealogy of Social Identity Theory. In T&T Clark Social Identity Commentary on the New Testament. Edited by J. Brian Tucker and Aaron Kuecker. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 1–24. Available online: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/lib/pretoria-ebooks/reader.action?docID=5993973&ppg=18 (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Schnelle, Udo. 2009. Theology of the New Testament. Translated by M. Eugene Boring. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, Available on Google Play Books. [Google Scholar]

- Siker, Jeffrey S. 2017. The Second and Third Centuries. In The Early Christian World, 2nd ed. Edited by Philip F. Esler. Routledge Worlds. London: Routledge, pp. 197–219. Available online: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/lib/pretoria-ebooks/reader.action?docID=4921825&ppg=228 (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Simmons, Michael B. 2017. Graeco-Roman Philosophical Opposition. In The Early Christian World, 2nd ed. Edited by Philip F. Esler. Routledge Worlds. London: Routledge, pp. 796–816. Available online: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/lib/pretoria-ebooks/reader.action?docID=4921825&ppg=827 (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Skarsaune, Oskar. 2018. Ethnic Discourse in Early Christianity. In Christianity in the Second Century, 1st ed. Edited by James C. Paget and Judith Lieu. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 250–64. [Google Scholar]

- St. Jerome. 1999. On Illustrious Men. Translated by Thomas P. Halton. The Fathers of the Church 100. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press. Available online: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/lib/pretoria-ebooks/reader.action?docID=3134802&ppg=2 (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Stowers, Stanley K. 2011. The Concept of “Community” and the History of Early Christianity. Method & Theory in the Study of Religion 23: 238–56. [Google Scholar]

- Strickland, Phillip D. 2017. The Curious Case of P72: What an Ancient Manuscript Can Tell Us about the Epistles of Peter and Jude. JETS 60: 781–91. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:229331142?utm_source=wikipedia (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Tajfel, Henri. 1970. Experiments in Intergroup Discrimination. Scientific American 223: 96–103. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24927662 (accessed on 6 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri. 1981. Human Groups and Social Categories: Studies in Social Psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, Henri, Michael G. Billig, R. P. Bundy, and Claude Flament. 1971. Social Categorization and Intergroup Behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology 1: 149–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testuz, Michel. 1958. Papyrus Bodmer V: Nativité de Marie. Cologny-Genéve: Bibliotheca Bodmeriana. [Google Scholar]

- Testuz, Michel. 1959a. Papyrus Bodmer VII-IX. Cologny-Genéve: Bibliotheca Bodmeriana. [Google Scholar]

- Testuz, Michel. 1959b. Papyrus Bodmer X-XII. Cologny-Genéve: Bibliotheca Bodmeriana. [Google Scholar]

- Testuz, Michel. 1960. Papyrus Bodmer XIII: Méliton de Sardes, Homélie sur la Pâque. Cologny-Genéve: Bibliotheca Bodmeriana. [Google Scholar]

- Trismegistos. n.d. Available online: https://www.trismegistos.org/text/220465 (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Vearncombe, Erin K. 2020. Kinship. In The Ancient Mediterranean Social World: A Sourcebook. Edited by Zeba A. Crook. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 50–63. Available online: https://search-ebscohost-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=2621762&site=ehost-live&scope=site&ebv=EK&ppid=Page-__-50 (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Volf, Miroslav. 1994. Soft Difference: Theological Reflections on the Relation Between Church and Culture in 1 Peter. Ex Auditu 10: 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Robyn F. 2021. The Origins of Early Christian Literature: Contextualizing the New Testament within Greco-Roman Literary Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University press. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, Tommy. 2005. Papyrus 72 and the Bodmer Miscellaneous Codex. New Testament Studies 51: 137–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Ritva H. 2020. Purity. In The Ancient Mediterranean Social World: A Sourcebook. Edited by Zeba A. Crook. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, pp. 192–206. Available online: https://search-ebscohost-com.uplib.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=2621762&site=ehost-live&scope=site&ebv=EK&ppid=Page-__-161 (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Zervos, George. 2019. The Protevangelium of James: Greek Text, English Translation, Critical Introduction Volume 1. Jewish and Christian Texts in Contexts and Related Studies 17. New York: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oliveira, N.L.D.; Kok, J. Codex and Contest: What an Early Christian Manuscript Reveals about Social Identity Formation Amid Persecution and Competing Christianities. Religions 2024, 15, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15010044

Oliveira NLD, Kok J. Codex and Contest: What an Early Christian Manuscript Reveals about Social Identity Formation Amid Persecution and Competing Christianities. Religions. 2024; 15(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleOliveira, Nycholas Lawrence David, and Jacobus (Kobus) Kok. 2024. "Codex and Contest: What an Early Christian Manuscript Reveals about Social Identity Formation Amid Persecution and Competing Christianities" Religions 15, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15010044

APA StyleOliveira, N. L. D., & Kok, J. (2024). Codex and Contest: What an Early Christian Manuscript Reveals about Social Identity Formation Amid Persecution and Competing Christianities. Religions, 15(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15010044