The Religious Leaders’ Perspectives on Corona Survey: Methods and Key Results

Abstract

1. Introduction

If the pandemic lowers the barrier to reform it will offer a rare chance to recast the social contract to favour those who have been shut out, and to peg back those who today enjoy entrenched privileges through the tax system, education and regulation. Perhaps the pandemic will enhance a sense of national and global solidarity … Yet that may prove to be wishful thinking. In the next 18 months everyone with an agenda will argue that the pandemic proves their point. After 2007–2009 politicians failed to deal with the grievances of ordinary people and the demand for change led to a surge in populism. The 90% economy threatens even greater suffering. The anger it creates may end up feeding protectionism, xenophobia and government interference on a scale not seen in decades. If … that is an outcome you would reject, it is time to start arguing for something better.(The Economist, 30 April 2020)

2. The Religious Leaders’ Perspective on Corona Survey: Research Design and Methodology

2.1. Scope

2.2. Thematic Focus

2.3. Structure and Implementation

2.4. Questionnaire

2.4.1. Questionnaire Section 1: Welcome

This survey aims to explore the perspectives of religious leaders on the current coronavirus pandemic. It is conducted by the Research Programme on Religious Communities and Sustainable Development at the Faculty of Theology of Humboldt Universität zu Berlin (Germany), led by Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Gräb and Philipp Öhlmann.

Any information provided will be solely used for the purposes of academic research. The findings will be published on the research programme’s website and also used for subsequent academic research and publications.

Questions can be skipped. You can choose to participate anonymously if you wish.

Should you have any questions, do not hesitate to contact the lead researchers of the survey, Marie-Luise Frost and Dr. Ekkardt Sonntag (corona-survey.theology@hu-berlin.de).

We would greatly appreciate to include your expertise and insight in our assessment and thank you for taking part in the survey.

Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Gräb, Philipp Öhlmann, Marie-Luise Frost, Juliane Stork, Dr. Ekkardt Sonntag.

By continuing, you indicate your consent for using your answers for academic research and publications.

2.4.2. Questionnaire Section 2: About You and Your Community

- Item 1: “Which of the following applies to you?”

- Type: Multiple choice (multiple selections possible)

- Answer options:

- (1)

- I am a leader or functionary in my religious community.

- (2)

- I am a social service or development practitioner in a religious NGO/FBO.

- (3)

- I am a leader or functionary in an interconfessional or interreligious organization.

- (4)

- I am an ordinary member of my religious community.

- (5)

- I am not a member of a religious community.

- (6)

- Please specify “other” [opens Item 1a—open ended].

- Note: Respondents were asked to indicate their position in the religious community. To be able to filter out any respondents who do not fall into the category of persons in religious leadership positions, answer options (4) and (5) were included. Functionaries of religious organizations might not hold leadership positions in their religious communities, but in accordance with the definition of persons in religious leadership positions outlined above, they were included in the survey. Hence, the selection of multiple answer options was possible. Moreover, option (6) opened a subitem (Item 1a), allowing the free-text specification of the respondent’s position.

- Item 2. “Some of the questions are open ended. In case we quote any of your statements, would you prefer to be quoted by name or anonymously (e.g., one leader said …)? Answers to multiple choice questions will always remain anonymous”.

- Type: Multiple choice (one selection possible)

- Answer options:

- (1)

- “Quote me by name”

- (2)

- “Quote me anonymously”

- Note: To give the respondents the possibility of receiving recognition for any statements made in the framework of the survey, respondents were given the choice to indicate their preference of being quoted by name or anonymously. If option (1) was selected, a subitem (Item 2a) opened, allowing the free-text specification of the name by which the respondent preferred to be quoted.

- Item 3. “Which statement describes your religious community or organization best? My community/organization …”

- Type: Multiple choice (one selection possible)

- Answer options:

- (1)

- “… is local”.

- (2)

- “… is national”.

- (3)

- “… stretches over more than one country”.

- (4)

- “… is global”.

- (5)

- “Not applicable/no answer”.

- Note: Item 3 asked for the geographic scope of the religious community, thereby obtaining an indication of the size and the scope of representation.

- Item 4. “Please indicate the country in which you are based”.

- Type: Multiple choice (one selection possible)

- Answer options: list of all countries.

- Item 5. “Gender”

- Type: Multiple choice (one selection possible)

- Answer options: f/m/d

- Item 6. “Name of your religious community or organization”

- Type: open ended

- Item 7. “Which of these terms describes best the religious community or organization you represent?”

- Type: multiple choice (multiple selections possible)

- Answer options:

- (1)

- Religious community (e.g., church, mosque etc.)

- (2)

- Association of different religious communities within the same religious tradition (interconfessional/ecumenical/Islamic supreme councils etc.)

- (3)

- Interfaith association

- (4)

- Not applicable/no answer

- Note: Item 7 provided information on the type of organization in which the respondent has their leadership position. If option (1) was selected, Item 7a opened, which asked for the approximate membership figure of the religious community.

- Item 7a. “Approximately how many members does your religious community have?”

- Type: multiple choice (one selection possible)

- Answer options:

- (1)

- Less than 100

- (2)

- 101–1000

- (3)

- 1001–10,000

- (4)

- 10,001–100,000

- (5)

- More than 100,000

- (6)

- Not applicable/no answer

- Note: Item 7a (conditional on the selection of option (1) in Item 7) provided an indication of the size in terms of membership of the respondent’s religious community.

- Item 8. “Your position in your religious community/organization”

- Type: multiple choice (one selection possible)

- Answer options:

- (1)

- Top leadership level

- (2)

- Intermediate leadership level

- (3)

- Local leadership level

- (4)

- Ordinary member

- (5)

- I am not a member of any religious community

- (6)

- Please specify “other” [opens Item 8a—open ended]

- Item 9. “Which of the following describes the tradition of your community or organization best? (Choose multiple for multi-faith or ecumenical associations)”

- Type: multiple choice (multiple selections possible)

- Answer options:

- (1)

- Muslim: Sunni

- (2)

- Muslim: Shia

- (3)

- Christian: Orthodox (including both Eastern and Oriental)

- (4)

- Christian: Roman (Latin) Catholic (including Eastern Rite)

- (5)

- Christian: Protestant (Lutheran, Reformed, Anglican, Methodist, etc.)

- (6)

- Christian: African Independent

- (7)

- Christian: Evangelical

- (8)

- Christian: Pentecostal, Charismatic

- (9)

- Druze

- (10)

- Yazidi

- (11)

- Alawi, Alewi

- (12)

- Bahai

- (13)

- Buddhist

- (14)

- Hindu

- (15)

- African Traditional Religion

- (16)

- Jewish

- Note. Multiple selections of religious traditions were allowed to cater for interconfessional or interreligious organizations.

2.4.3. Questionnaire Section 3: Your Community

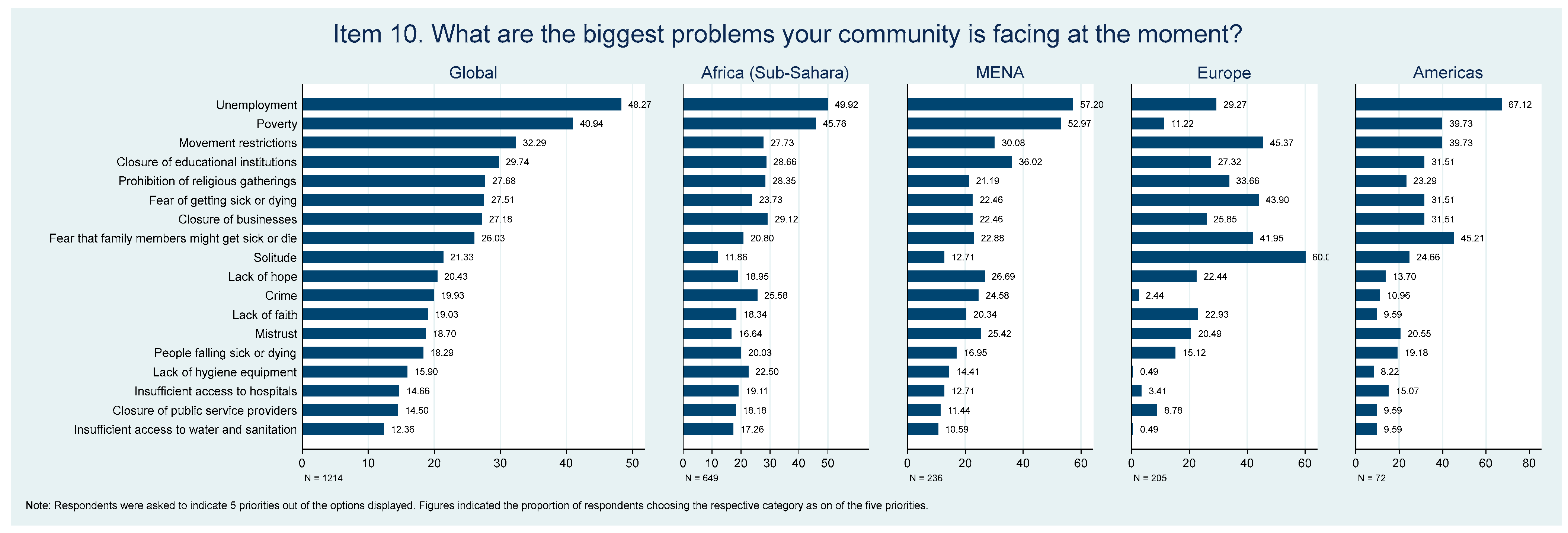

- Item 10. “What are the biggest problems your community is facing at the moment? (Please choose the top five priorities out of the following options)”

- Type: multiple choice (up to five selections possible)

- Answer options:

- (1)

- Closure of public service providers

- (2)

- Fear that family members might get sick or die

- (3)

- Prohibition of religious gatherings

- (4)

- Mistrust

- (5)

- Closure of educational institutions

- (6)

- Unemployment

- (7)

- Lack of faith

- (8)

- Fear of getting sick or dying

- (9)

- Insufficient access to hospitals

- (10)

- Crime

- (11)

- Poverty

- (12)

- Movement restrictions

- (13)

- Lack of hygiene equipment (e.g., hand sanitizers, masks, disinfectants)

- (14)

- Closure of businesses

- (15)

- Insufficient access to water and sanitation

- (16)

- Solitude

- (17)

- People falling sick or dying

- (18)

- Lack of hope

- Note: Answer options in Item 10 were randomized to prevent bias toward the options listed at the top. The answer options were developed by the research team based on earlier research on religious leaders’ responses on what constituted the major problems in their communities (Öhlmann et al. 2021, p. 26) and were expanded and adapted in light of the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Item 11. “What is your assessment of domestic violence in your community during the coronavirus pandemic?”

- Type: open ended

- Note: Item 11 was originally not included in the survey. It was added a few months into the survey, as domestic violence emerged as one of the most important problems during lockdowns in the pandemic (UN Women 2021).

- Item 12. “In your view, how high is the risk to get infected with the coronavirus in your city, town or local community?”

- Type: Likert scale (very low/low/medium/high/very high)

- Note: Item 12 served to assess the respondents’ perception of the risk of infection with COVID-19.

- Item 13. “How does the coronavirus affect religious practice in your faith community?”

- Type: multiple choice (one selection possible)

- Answer options:

- (1)

- We still come together for religious services/ceremonies/events/prayer, much in the same way as always.

- (2)

- We come together for religious services/ceremonies/events/prayer but in much smaller numbers than before.

- (3)

- We hold our regular religious services/ceremonies/events/prayer online.

- (4)

- We do not hold religious services/ceremonies/events/prayer at all.

- (5)

- Not applicable/no answer.

- Note: Item 13 served to assess the impact of COVID-19 and the related lockdowns on religious gatherings.

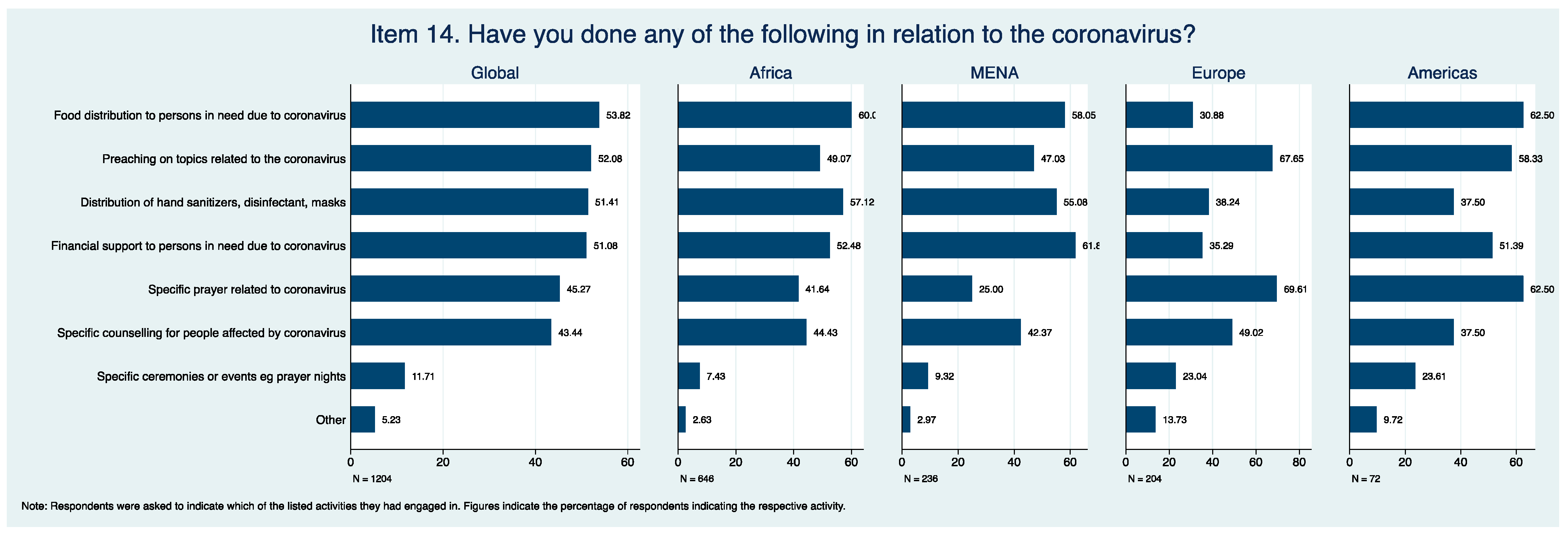

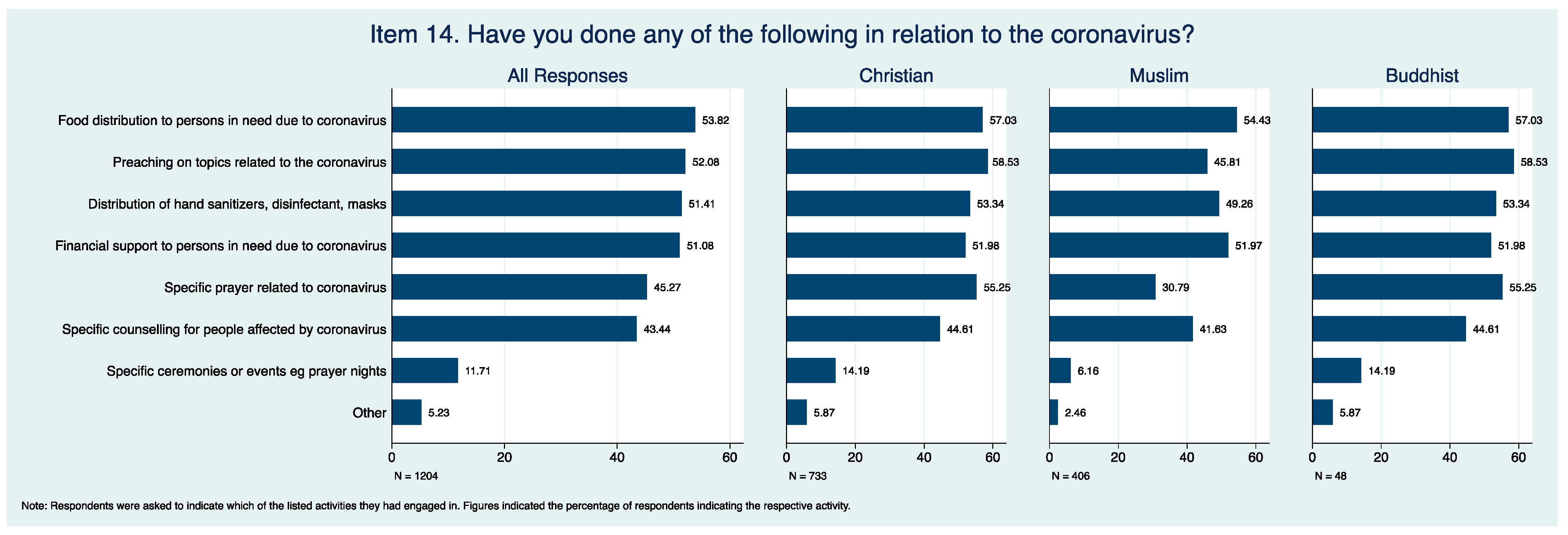

- Item 14. “Have you done any of the following in relation to the coronavirus?”

- (1)

- Preaching on topics related to the coronavirus pandemic

- (2)

- Specific prayer related to coronavirus

- (3)

- Specific ceremonies or events, e.g., prayer nights relating to coronavirus

- (4)

- Food distribution to persons in need due to coronavirus

- (5)

- Financial support to persons in need due to coronavirus

- (6)

- Distribution of hand sanitizers, disinfectants or masks

- (7)

- Specific counseling for people affected by coronavirus

- (8)

- Other (please specify)

- Notes: Answer option (3) opened Item 14a: “Which specific ceremonies have you held?” This question was open ended, providing the opportunity to specify further activities embarked upon during the pandemic.

- Answer option (8) opened Item 14b, which was open ended, providing the opportunity to specify further activities embarked upon during the pandemic.

- Item 15. “Is there a specific reference from scripture and/or tradition that you have used in relation to the coronavirus pandemic?”

- Type: open ended

- Note: Item 15 allowed respondents to refer to specific scriptures from their religious tradition (e.g., Bible verses, Quranic suras)

2.4.4. Questionnaire Section 4: Messages to Your Community

- Item 16. “What is the most important message you have given to your religious community concerning the coronavirus pandemic and the related measures?”

- Type: open ended

- Note: In light of ambiguous messaging by religious leaders at the beginning of the pandemic, Item 16 probed into what kind of messages religious leaders spread during the pandemic.

- Item 17. “What is the most important message you would like to give your government regarding the pandemic and related measures?”

- Type: open ended

- Note: Item 17 relates to the relationship of religious communities to the state with the aim of finding out whether religious leaders supported or criticized the government’s actions during the pandemic.

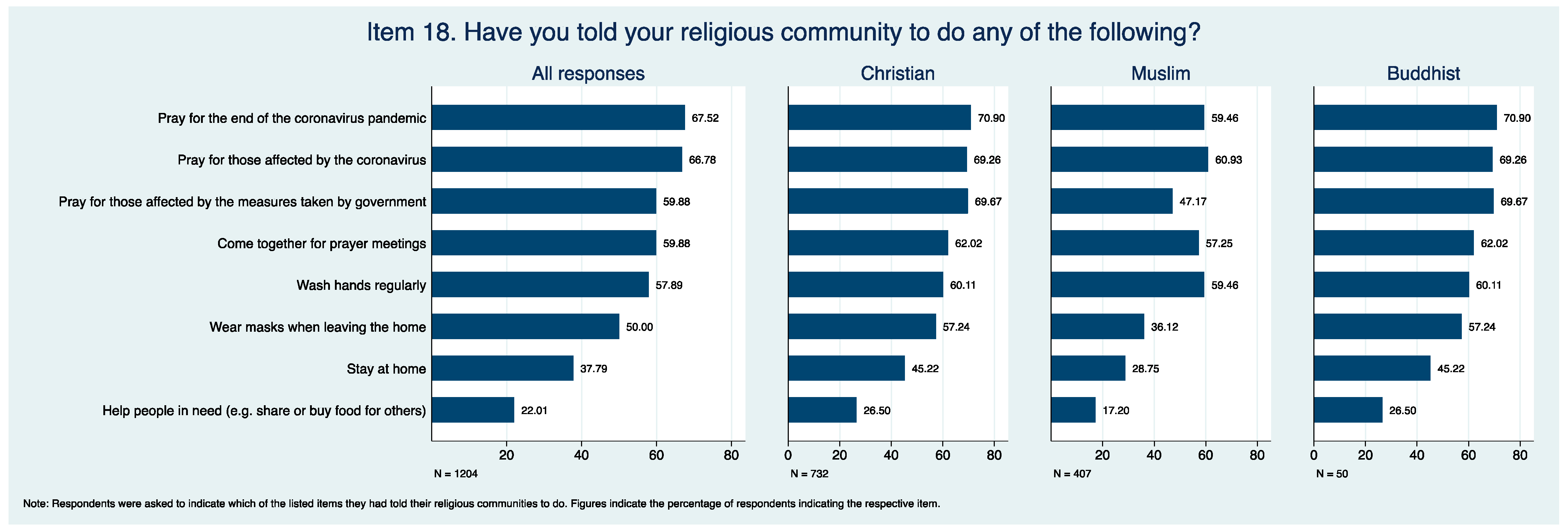

- Item 18.

- Type: multiple choice (multiple selection possible)

- Question: “Have you told your religious community to do any of the following?”

- Answer options:

- (1)

- Pray for the end of the coronavirus pandemic.

- (2)

- Pray for those affected by the coronavirus.

- (3)

- Pray for those affected by the measures taken by the government related to the pandemic.

- (4)

- Come together for prayer meetings.

- (5)

- Wash hands regularly.

- (6)

- Wear masks when leaving the home.

- (7)

- Stay at home.

- (8)

- Help people in need (e.g., share or buy food for others).

- Note: Item 18 was intended to find out what kind of messages religious leaders promoted during the pandemic and, in particular, whether these messages related to spirituality, health measures, or social behavior.

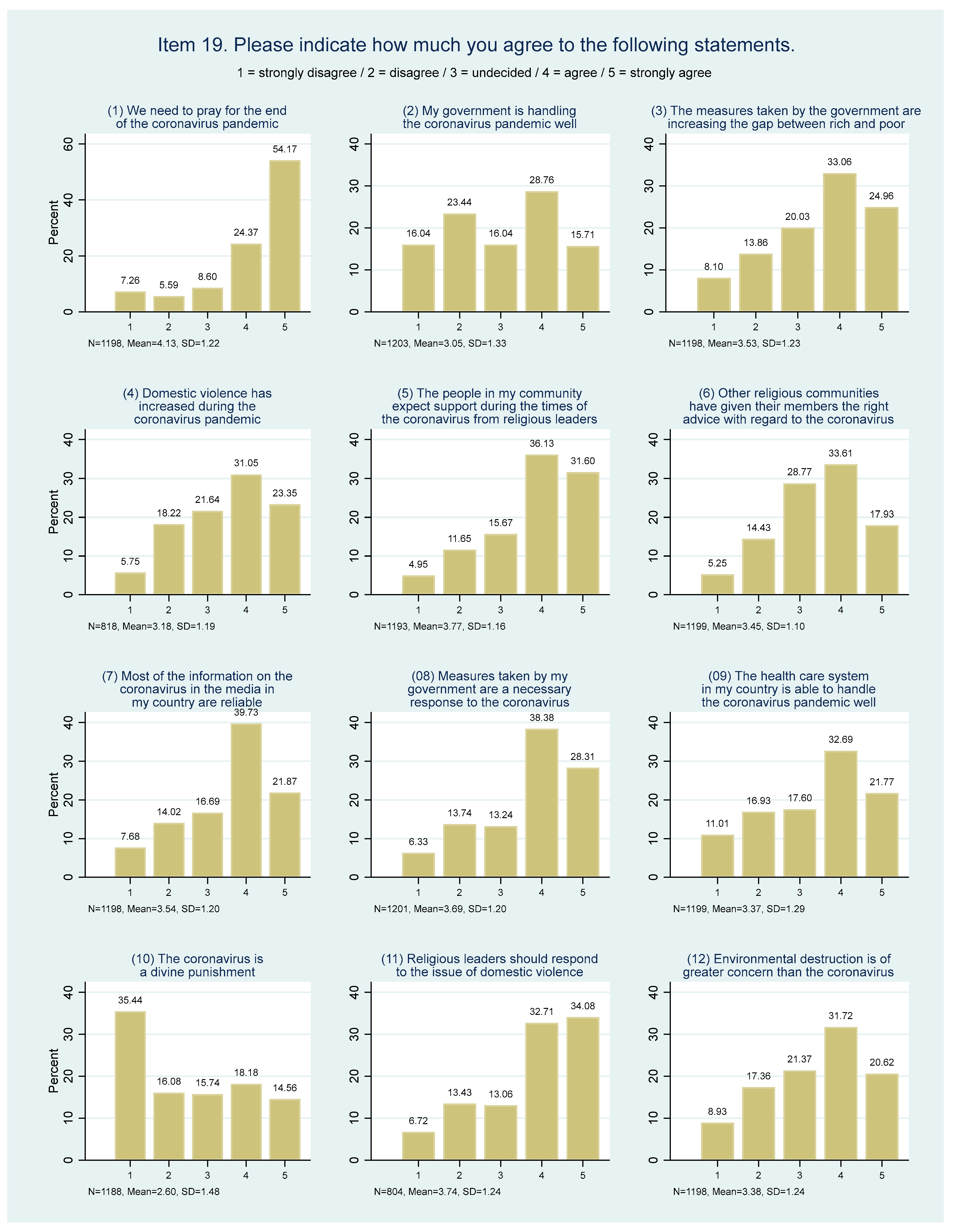

- Item 19. “Please indicate how much you agree with the following statements”.

- Statements provided:

- (1)

- We need to pray for the end of the coronavirus pandemic.

- (2)

- My government is handling the coronavirus pandemic well.

- (3)

- The measures taken by the government are increasing the gap between rich and poor.

- (4)

- Domestic violence has increased during the coronavirus pandemic.

- (5)

- The people in my community expect support during the times of the coronavirus from religious leaders.

- (6)

- Other religious communities have given their members the right advice with regard to the coronavirus.

- (7)

- Most of the information on the coronavirus in the media in my country are reliable.

- (8)

- Measures taken by my government (lockdown, movement restrictions, closures etc.) are a necessary response to the coronavirus.

- (9)

- The health care system in my country is able to handle the coronavirus pandemic well.

- (10)

- The coronavirus is a divine punishment.

- (11)

- Religious leaders should respond to the issue of domestic violence.

- (12)

- Environmental destruction is of greater concern than the coronavirus.

- Type: Likert scale (strongly agree/agree/undecided/disagree/strongly disagree)

- Note: Item 19 provided 12 statements and asked respondents to indicate to what extent they agreed with the statement on a five-point scale. The statements appeared in randomized order. Subitems (4) and (11) were included at a later stage, at the same time as Item 11 was added to the survey.

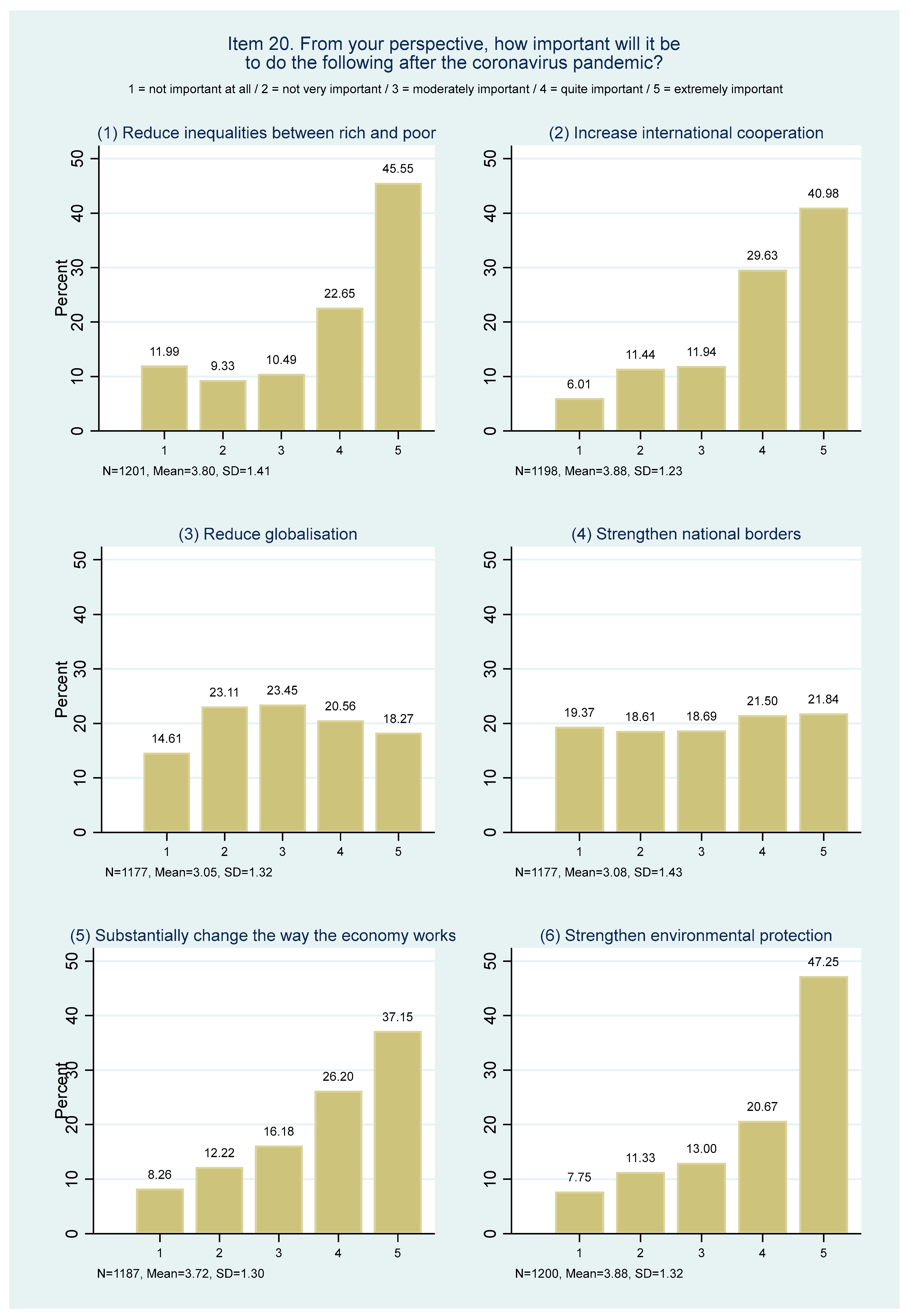

- Item 20. “From your perspective, how important will it be to do the following after the coronavirus pandemic?”

- Statements provided:

- (1)

- Reduce inequalities between rich and poor.

- (2)

- Increase international cooperation.

- (3)

- Reduce globalization.

- (4)

- Strengthen national borders.

- (5)

- Substantially change the way the economy works.

- (6)

- Strengthen environmental protection.

- Type: Likert scale (not important at all/not very important/moderately important/quite important/extremely important)

- Note: Item 20 provided six statements and asked respondents to indicate the importance of each on a five-point scale. Answer options were randomized.

2.4.5. Questionnaire Section 5: Vision for the Time After the Coronavirus Pandemic

- Item 21. “What is your vision for your country and the world after the coronavirus pandemic?”

- Type: open ended

- Note: Item 21 served to explore the normative notions on post-Covid society held by religious leaders. Hence, an open ended question was chosen.

2.4.6. Questionnaire Sections 6 and 7

3. Description of the Data

3.1. Descriptive Statistics; Regional and Religious Distribution

Information on the Respondents

3.2. Religious Communities During the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.2.1. The Biggest Problems During the Pandemic [Item 10]

3.2.2. Risk of Infection [Item 12]

3.2.3. Effects of the Pandemic on Religious Practice [Item 13]

3.2.4. Services Provided During the COVID-19 Pandemic [Item 14]

3.2.5. Messages to the Community [Item 18]

3.2.6. Attitudes and Views [Item 19]

3.2.7. Perspectives on the Post-Pandemic Future [Item 20]

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Survey Dataset

4.2. Key Findings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | https://www.unicef.org/rosa/stories/religious-and-faith-leaders-join-hands-protect-women-and-children (accessed on 1 June 2024); https://www.afro.who.int/news/religious-leaders-join-covid-19-fight-africa (accessed on 1 June 2024); https://blogs.bmj.com/bmjgh/2023/03/07/faith-leaders-in-the-fight-against-the-pandemic/ (accessed on 1 June 2024); cf. also DeMora et al. (2021). |

| 2 | In some of the analyses and overviews to follow, Latin America and the Caribbean and North America were grouped together as the Americas. |

| 3 | It should be noted that the figures for the Americas are less robust due to the relatively low number of observations in the region (N = 72). |

| 4 | Interestingly, in the Americas elements of both spiritual and material support are mentioned frequently (by around 60% of the respondents; but these figures have to be treated with extra care due to the low number of responses from the region). |

References

- Alfano, Vincenzo. 2023. God or Good Health? Evidence on Belief in God in Relation to Public Health During a Pandemic. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 107: 102098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, Vincenzo, Salvatore Ercolano, and Gaetano Vecchione. 2023. In COVID We Trust: The Impact of The Pandemic on Religiousness—Evidence from Italian Regions. Journal of Religion and Health 62: 1358–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amankwah-Amoah, Joseph, Zaheer Khan, Geoffrey Wood, and Gary Knight. 2021. COVID-19 and Digitalization: The Great Acceleration. Journal of Business Research 136: 602–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, Chittaranjan. 2020. The Limitations of Online Surveys. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 42: 575–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arndt, Channing, Rob Davies, Sherwin Gabriel, Laurence Harris, Konstantin Makrelov, Sherman Robinson, Stephanie Levy, Witness Simbanegavi, Dirk van Seventer, and Lillian Anderson. 2020. COVID-19 Lockdowns, Income Distribution, and Food Security: An Analysis for South Africa. Global Food Security 26: 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzen, Jeanet Sinding. 2021. In Crisis, We Pray: Religiosity and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 192: 541–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bettinger-Lopez, Caroline, and Alexandra Bro. 2020. A Double Pandemic: Domestic Violence in the Age of COVID-19. Domestic Violence Report 25: 85–6. [Google Scholar]

- DeMora, Stephanie L., Jennifer L. Merolla, Brian Newman, and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister. 2021. Reducing Mask Resistance among White Evangelical Christians with Value-consistent Messages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118: e2101723118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstadt, Shmuel N. 1968. The Protestant Ethic Thesis in an Analytical and Comparative Framework. In The Protestant Ethic and Modernization: A Comparative View. Edited by Shmuel N. Eisenstadt. New York and London: Basic Books, pp. 3–45. [Google Scholar]

- Essa-Hadad, Jumanah, Nour Abed Elhadi Shahbari, Daniel Roth, and Anat Gesser-Edelsburg. 2022. The Impact of Muslim and Christian Religious Leaders Responding to COVID-19 in Israel. Frontiers in Public Health 10: 1061072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frahm-Arp, Maria. 2021. Pneumatology and Prophetic Pentecostal Charismatic Christianity during COVID-19 in South Africa. In The Use and Abuse of the Spirit in Pentecostalism: A South African Perspective. Edited by Mookgo S. Kgatle and Allan Anderson. Routledge New Critical Thinking in Religion, Theology and Biblical Studies. Abingdon, Oxon and New York: Routledge, pp. 150–74. [Google Scholar]

- Frahm-Arp, Maria. 2024. Problematizing Confession and Forgiveness in Prophetic Pentecostal Christianity: A Case Study of Rabboni Centre Ministries. Journal for the Study of Religion 36: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, Marie-Luise. 2023. “There Is a Silent War Going On”—African Religious Leaders’ Perspectives on Domestic Violence before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Religions 14: 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, Marie-Luise, and Philipp Öhlmann. 2021. “More Than Just Having Church”: COVID-19 and African Initiated Churches. Kurzstellungnahmen des Forschungsbereichs Religiöse Gemeinschaften und nachhaltige Entwicklung 1/2021. Available online: https://www.rcsd.hu-berlin.de/en/publications/policy-brief-01-2021-more-than-just-having-church.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Gkeredakis, Manos, Hila Lifshitz-Assaf, and Michael Barrett. 2021. Crisis as Opportunity, Disruption and Exposure: Exploring Emergent Responses to Crisis through Digital Technology. Information and Organization 31: 100344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, Kelsey E., Rina James, Eric T. Bjorklund, and Terrence D. Hill. 2021. Conservatism and Infrequent Mask Usage: A Study of US Counties During the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic. Social Science Quarterly 102: 2368–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, Ellen, and Kathryn Kraft. 2022. Mental Health and Spiritual Well-Being in Humanitarian Crises: The Role of Faith Communities Providing Spiritual and Psychosocial Support During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of International Humanitarian Action 7: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harapan, Harapan, Noelle Shields, Aparna G. Kachoria, Abigail Shotwell, and Abram L. Wagner. 2021. Religion and Measles Vaccination in Indonesia, 1991–2017. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 60: S44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillenbrand, Carolin. 2020. Studie zu Religion und gesellschaftlichem Zusammenhalt in Zeiten der Corona-Pandemie: Ergebnisse für den 1. Zeitraum von Juli bis Oktober 2020. Factsheet. Available online: https://www.uni-muenster.de/imperia/md/content/religion_und_politik/aktuelles/2020/11_2020/factsheet__religion_und_gesellschaftlicher_zusammenhalt_in_zeiten_der_corona-pandemie.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Hillenbrand, Carolin. 2023. Social Cohesion and Religiosity—Empirical Results from an Online Survey in Germany during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Religion and Development 2: 213–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillenbrand, Carolin, Detlef Pollack, and Yasemin El-Menouar. 2023. Religion als Ressource der Krisenbewältigung? Religionsmonitor 2023. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung. [Google Scholar]

- Hopgood, Daniel A., Kendrah Cunningham, and Ilana R. Azulay Chertok. 2024. Religious Leaders’ Perspectives on Rural Communities’ Responses During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the USA. Journal of Religion and Health 63: 725–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanol, Eylem, and Ines Michalowski. 2023. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Religiosity: Evidence from Germany. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 62: 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanozia, Rubal, and Ritu Arya. 2021. “Fake News”, Religion, and COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Media Asia 48: 313–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasstan, Ben. 2021. “If a Rabbi Did Say ‘You Have to Vaccinate,’ We Wouldn’t”: Unveiling the Secular Logics of Religious Exemption and Opposition to Vaccination. Social Science & Medicine 280: 114052. [Google Scholar]

- Lakemann, Tabea, Jann Lay, and Tevin Tafese. 2020. Africa after the COVID-19 Lockdowns: Economic Impacts and Prospects. GIGA-Focus. Afrika (6). Available online: https://www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus/africa-after-the-covid-19-lockdowns-economic-impacts-and-prospects (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Lawler, Odette K., Hannah L. Allan, Peter W. J. Baxter, Romi Castagnino, Marina Corella Tor, Leah E. Dann, Joshua Hungerford, Dibesh Karmacharya, Thomas J. Lloyd, María José López-Jara, and et al. 2021. The COVID-19 Pandemic Is Intricately Linked to Biodiversity Loss and Ecosystem Health. The Lancet. Planetary Health 5: e840–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohommad, Adil, and Evgenia Pugacheva. 2022. Impact of COVID-19 on Attitudes to Climate Change and Support for Climate Policies: Working Paper No. 2022/023. IMF Working Paper. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2022/02/04/Impact-of-COVID-19-on-Attitudes-to-Climate-Change-and-Support-for-Climate-Policies-512760 (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Nche, George C., Uchechukwu M. Agbo, and Malachy I. Okwueze. 2024. Church Leader’s Interpretation of COVID-19 in Nigeria: Science, Conspiracies, and Spiritualization. Journal of Religion and Health 63: 741–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. 2021. OECD Science, Technology and Innovation Outlook 2020: Times of Crisis and Opportunity. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/oecd-science-technology-and-innovation-outlook-2021_75f79015-en (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Omidvar Tehrani, Shadi, and Douglas D. Perkins. 2022. Public Health Resources, Religion, and Freedom as Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccination Rates: A Global Study of 89 Countries. COVID 2: 703–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Tutu, Annabella, Adjeiwa Akosua Affram, Christopher Mensah-Sarbah, Vivian A. Dzokoto, and Glenn Adams. 2021. The Impact of COVID-19 and Religious Restrictions on the Well-Being of Ghanaian Christians: The Perspectives of Religious Leaders. Journal of Religion and Health 60: 2232–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öhlmann, Philipp, and Ignatius Swart. 2022. Religion and Environment. Exploring the Ecological Turn in Religious Traditions, the Religion and Development Debate and Beyond. Religion & Theology 29: 292–321. [Google Scholar]

- Öhlmann, Philipp, Marie-Luise Frost, and Wilhelm Gräb. 2021. Potentials of Cooperation with African Initiated Churches for Sustainable Development: Summary of Research Results and Policy Recommendations for German Development Policy. Berlin: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Available online: https://www.rcsd.hu-berlin.de/de/publikationen/pdf-dateien/oehlmann-frost-graeb-2021-potentials-african.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Pew Research Center. 2023. How COVID-19 Restrictions Affected Religious Groups Around the World in 2020. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2022/11/29/how-covid-19-restrictions-affected-religious-groups-around-the-world-in-2020/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Pew Research Center. 2024. Globally, Government Restrictions on Religion Reached Peak Levels in 2021, While Social Hostilities Went Down. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2024/03/PR_2024.3.5_religious-restrictions_REPORT.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Ruan, Rongping, Kenneth R. Vaughan, and Dan Han. 2023. Trust in God: The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Impact on Religiosity in China. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 62: 523–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, Rachel C., Anna C. Snavely, Maria De Jesus, Megan D. Othus, and Jennifer D. Allen. 2013. HPV Vaccine Decision-Making and Acceptance: Does Religion Play a Role? Journal of Religion and Health 52: 1120–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibanda, Fortune, Tenson Muyambo, and Ezra Chitando. 2022. Introduction: Religion and Public Health in the Shadow of COVID-19 Pandemic in Southern Africa. In Religion and the COVID-19 Pandemic in Southern Africa. Edited by Fortune Sibanda, Tenson Muyambo and Ezra Chitando. London: Routledge, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sisti, Leuconoe Grazia, Danilo Buonsenso, Umberto Moscato, Gianfranco Costanzo, and Walter Malorni. 2023. The Role of Religions in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, Ekkardt, Marie-Luise Frost, and Philipp Öhlmann. 2020. Religious Leaders’ Perspectives on Corona—Preliminary Findings. Policy Brief 03/2020 of the Research Programme on Religious Communities and Sustainable Development. Berlin: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Available online: https://www.rcsd.hu-berlin.de/en/publications/policy-brief-03-2020-religious-leaders.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- United Nations COVID-19 Response. n.d. What Is Domestic Abuse? Available online: https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/what-is-domestic-abuse (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- UN Women. 2021. Measuring the Shadow Pandemic: Violence Against Women During COVID-19. Rome: United Nations. Available online: https://data.unwomen.org/publications/vaw-rga (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Verschuur, Jasper, Elco E. Koks, and Jim W. Hall. 2021. Global Economic Impacts of COVID-19 Lockdown Measures Stand Out in High-Frequency Shipping Data. PLoS ONE 16: e0248818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | Mean/% | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Position | ||||||

| 1.1 Leader or functionary in religious community | 1211 | 48.22 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 1.2 Social service or development practitioner in rel. NGO/FBO | 1211 | 13.38 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 1.3 Leader or functionary in interconfessional or interreligious organization | 1211 | 11.23 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 1.4 Ordinary member of religious community | 1211 | 14.70 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 1.5 Not a member of religious community | 1211 | 1.65 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 1.6 Other | 1211 | 22.63 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 1a Specify other | 20 | Qualitative | ||||

| 2 Quote by name | 1223 | 38.84 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 2a Name | 423 | Qualitative | ||||

| 3 Geographic scope of religious community | 1185 | 2.40 | 0.98 | 1 | 4 | |

| 4 Country | 1187 | See appendix for per-country figures | ||||

| 5 Gender | ||||||

| 5.1 Diverse | 1214 | 0.25 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 5.1 Female | 1214 | 33.77 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 5.1 Male | 1214 | 65.98 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 6 Name of religious community/organization | 1111 | Qualitative | ||||

| 7 Type of religious community or organization | ||||||

| 7.1 Religious community | 1206 | 79.35 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 7.2 Association of different religious communities within same religious tradition | 1206 | 13.76 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 7.3 Interfaith association | 1206 | 6.22 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 7.4 Not applicable | 1206 | 4.73 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 7a Size of religious community | 923 | 3.80 | 1.42 | 1 | 5 | |

| 8 Leadership level | ||||||

| 8.1 Top leadership level | 1216 | 34.13 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 8.2 Intermediate leadership level | 1216 | 24.84 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 8.3 Local leadership level | 1216 | 23.93 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 8.4 Ordinary member | 1216 | 14.31 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 8.5 I am not a member of any religious community | 1216 | 1.56 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 8.6 Other | 1216 | 1.23 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 8a Specification of other | 14 | Qualitative | ||||

| 9 Religious affiliation | ||||||

| 9.1 Muslim: Sunni | 1198 | 26.63 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 9.2 Muslim: Shia | 1198 | 9.60 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 9.3 Christian: Orthodox | 1198 | 4.51 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 9.4 Christian: Roman Catholic | 1198 | 12.10 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 9.5 Christian: Protestant | 1198 | 31.30 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 9.6 Christian: African Independent | 1198 | 9.02 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 9.7 Christian: Evangelical | 1198 | 9.52 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 9.8 Christian: Pentecostal, Charismatic | 1198 | 10.10 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 9.9 Druze | 1198 | 0.75 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 9.10 Yazidi | 1198 | 0.33 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 9.11 Alawi, Alewi | 1198 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 9.12 Bahai | 1198 | 0.92 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 9.13 Buddhist | 1198 | 4.42 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 9.14 Hindu | 1198 | 0.42 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 9.15 African Traditional Religion | 1198 | 0.67 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 9.16 Jewish | 1196 | 0.59 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10 Biggest problems | ||||||

| 10.1 Closure of public service providers | 1214 | 20.43 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.2 Fear that family members might get sick or die | 1214 | 19.03 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.3 Prohibition of religious gatherings | 1214 | 21.33 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.4 Mistrust | 1214 | 18.70 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.5 Closure of educational institutions | 1214 | 15.90 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.6 Unemployment | 1214 | 14.66 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.7 Lack of faith | 1214 | 12.36 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.8 Fear of getting sick or dying | 1214 | 27.51 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.9 Insufficient access to hospitals | 1214 | 26.03 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.10 Crime | 1214 | 18.29 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.11 Poverty | 1214 | 48.27 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.12 Movement restrictions | 1214 | 40.94 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.13 Lack of hygiene equipment | 1214 | 19.93 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.14 Closure of businesses | 1214 | 32.29 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.15 Insufficient access to water and sanitation | 1214 | 14.50 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.16 Solitude | 1214 | 27.18 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.17 People falling sick or dying | 1214 | 29.74 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 10.18 Lack of hope | 1214 | 27.68 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 11 Domestic violence in community | 676 | Qualitative | ||||

| 12 Perceived risk of infection | 1207 | 2.69 | 1.07 | 1 | 5 | |

| 13 How does the coronavirus affect religious practice in your faith community? | ||||||

| 13.1 We still come together for religious services (…) much in the same way as always | 927 | 5.29 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 13.2 We come together for religious services (…) but in much smaller numbers than before | 927 | 44.77 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 13.3 We hold our regular religious services (…) online | 927 | 17.69 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 13.4 We do not hold religious services (…) at all | 927 | 32.25 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 14 Actions in relation to the pandemic | ||||||

| 14.1 Preaching on topics related to the pandemic | 1204 | 52.08 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 14.2 Specific prayer related to coronavirus | 1204 | 45.27 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 14.3 Specific ceremonies or events | 1204 | 11.71 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 14.4 Food distribution to persons in need due to coronavirus | 1204 | 53.82 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 14.5 Financial support to persons in need due to coronavirus | 1204 | 51.08 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 14.6 Distribution of hand sanitizers, disinfectants or masks | 1204 | 51.41 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 14.7 Specific counseling for people affected by coronavirus | 1204 | 43.44 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 14.8 Other | 1204 | 5.23 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 14a Specific ceremonies | 94 | Qualitative | ||||

| 14b Specification of other | 58 | Qualitative | ||||

| 15 Reference from scripture and/or tradition used in relation to the coronavirus pandemic | 723 | Qualitative | ||||

| 16 Most important message to religious community | 880 | Qualitative | ||||

| 17 Most important message to government | 838 | Qualitative | ||||

| 18 Messages to religious community | ||||||

| 18.1 Pray for the end of the coronavirus pandemic | 1204 | 57.89 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 18.2 Pray for those affected by the coronavirus | 1204 | 59.88 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 18.3 Pray for those affected by the measures taken by the government related to the pandemic | 1204 | 37.79 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 18.4 Come together for prayer meetings | 1204 | 22.01 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 18.5 Wash hands regularly. | 1204 | 67.52 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 18.6 Wear masks when leaving the home | 1204 | 66.78 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 18.7 Stay at home | 1204 | 59.88 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 18.8 Help people in need | 1204 | 50.00 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 19 Agreement with various pandemic-related statements | ||||||

| 19.1 We need to pray for the end of the coronavirus pandemic | 1198 | 4.13 | 1.22 | 1 | 5 | |

| 19.2 My government is handling the coronavirus pandemic well | 1,203 | 3.05 | 1.34 | 1 | 5 | |

| 19.3 The measures taken by the government are increasing the gap between rich and poor | 1198 | 3.53 | 1.23 | 1 | 5 | |

| 19.4 Domestic violence has increased during the coronavirus pandemic | 818 | 3.48 | 1.19 | 1 | 5 | |

| 19.5 The people in my community expect support during the times of the coronavirus from religious leaders | 1193 | 3.78 | 1.16 | 1 | 5 | |

| 19.6 Other religious communities have given their members the right advice with regard to the coronavirus | 1199 | 3.45 | 1.10 | 1 | 5 | |

| 19.7 Most of the information on the coronavirus in the media in my country are reliable | 1198 | 3.54 | 1.20 | 1 | 5 | |

| 19.8 Measures taken by my government are a necessary response to the coronavirus | 1201 | 3.69 | 1.20 | 1 | 5 | |

| 19.9 The health care system in my country is able to handle the coronavirus pandemic well | 1199 | 3.37 | 1.29 | 1 | 5 | |

| 19.10 The coronavirus is a divine punishment | 1188 | 2.60 | 1.48 | 1 | 5 | |

| 19.11 Religious leaders should respond to the issue of domestic violence | 804 | 3.74 | 1.24 | 1 | 5 | |

| 19.12 Environmental destruction is of greater concern than the coronavirus | 1198 | 3.38 | 1.24 | 1 | 5 | |

| 20 Importance after the pandemic | ||||||

| 20.1 Reduce inequalities between rich and poor | 1201 | 3.80 | 1.41 | 1 | 5 | |

| 20.2 Increase international cooperation | 1198 | 3.88 | 1.23 | 1 | 5 | |

| 20.3 Reduce globalization | 1177 | 3.05 | 1.32 | 1 | 5 | |

| 20.4 Strengthen national borders | 1177 | 3.08 | 1.43 | 1 | 5 | |

| 20.5 Substantially change the way the economy works | 1187 | 3.72 | 1.30 | 1 | 5 | |

| 20.6 Strengthen environmental protection | 1200 | 3.88 | 1.32 | 1 | 5 | |

| 21 Vision for country and world after the pandemic | 814 | Qualitative | ||||

| Region | N | % | Countries (Ncountry) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 652 | 54.93 | Nigeria (89), Kenya (37), Namibia (36), Cameroon (29), South Africa (26), South Sudan (26), Botswana (25), Liberia (25), Ethiopia (24), Ghana (24), Lesotho (23), Uganda (23), Chad (22), Comoros (the), (22), Malawi (22), Angola (21), Guinea-Bissau (21), Congo (the), (20), Eswatini (20), Mali (20), Sudan (the), (20), Gambia (15), Benin (14), Rwanda (12), Eritrea (5), Togo (5), United Republic of Tanzania (5), Burkina Faso (3), Democratic Republic of the Congo (3), Sierra Leone (3), Zambia (3), Mozambique (2), Zimbabwe (2), Burundi (1), Central African Republic (1), Gabon (1), Sao Tome and Principe (1), Seychelles (1) |

| Middle East and North Africa | 238 | 20.05 | Jordan (49), Morocco (42), Egypt (34), Iraq (33), Djibouti (21), Tunisia (16), Lebanon (14), Qatar (8), Algeria (6), Syria (4), Palestine (3), Bahrain (2), Oman (2), Iran (1), Kuwait (1), Libya (1), Saudi Arabia (1) |

| Europe | 208 | 17.52 | Germany (97), Switzerland (34), United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (32), Austria (21), France (5), Belgium (3), Italy (3), Spain (3), Netherlands (2), Denmark (1), Finland (1), Greece (1), Iceland (1), Luxembourg (1), Malta (1), Poland (1), Portugal (1) |

| Americas | 74 | 6.24 | Brazil (21), United States of America (10), Uruguay (9), Argentina (8), Colombia (5), Mexico (5), Chile (3), Costa Rica (2), Cuba (2), Ecuador (2), El Salvador (2), Venezuela (2), Canada (1), Guatemala (1), Nicaragua (1) |

| Asia | 10 | 0.84 | India (3), China (2), Malaysia (2), Azerbaijan (1), Indonesia (1), Myanmar (1) |

| Oceania | 5 | 0.42 | Australia (4), New Zealand (1) |

| Religion | N | Percent | Categories Included |

|---|---|---|---|

| Christian | 718 | 59.93 | Christian: Orthodox; Christian: Roman Catholic; Christian: Protestant; Christian: African Independent; Christian: Evangelical; Christian: Pentecostal, Charismatic |

| Muslim | 396 | 33.06 | Muslim: Sunni; Muslim: Shia |

| Buddhist | 50 | 4.17 | Buddhist |

| Other | 34 | 2.84 | Druze; Yazidi; Alawi, Alewi; Bahai; Hindu; African Traditional Religion; Jewish |

| Christian | Muslim | Buddhist | Other | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 402 | 222 | 0 | 12 | 636 |

| (63.21%) | (34.91%) | (1.89%) | |||

| Middle East and North | 56 | 163 | 0 | 13 | 232 |

| (24.14%) | (70.26%) | (5.60%) | |||

| Europe | 154 | 3 | 44 | 6 | 207 |

| (74.40%) | (1.45%) | (21.26%) | (2.90%) | ||

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 60 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 62 |

| (96.77%) | (0.00%) | (3.23%) | |||

| North America | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 11 |

| (81.82%) | (9.09%) | (9.09%) | |||

| Asia | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| (88.89%) | (11.11%) | ||||

| Oceania | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| (100.00%) | |||||

| Total | 694 | 390 | 45 | 33 | 1162 |

| (59.72%) | (33.56%) | (3.87%) | (2.84%) |

| Value | Percentage of Responses (Global) |

|---|---|

| 5 = very high | 5.55 |

| 4 = high | 15.66 |

| 3 = medium | 34.96 |

| 2 = low | 29.74 |

| 1 = very low | 14.08 |

| Region | Mean | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 2.61 | 1.09 | 645 |

| MENA | 2.95 | 1.07 | 233 |

| Europe | 2.45 | 0.86 | 206 |

| Americas | 3.34 | 1.03 | 73 |

| Percentage of Responses by Region | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | Africa | MENA | Europe | Americas | |

| 13.1 We still come together for religious services/ceremonies/events/prayer, much in the same way as always. | 5.29 | 3.11 | 5 | 8.14 | 1.79 |

| 13.2 We come together for religious services/ceremonies/events/prayer but in much smaller numbers than before. | 44.77 | 39.21 | 47.22 | 62.79 | 25 |

| 13.3 We hold our regular religious services/ceremonies/events/prayer online. | 17.69 | 9.96 | 13.89 | 27.33 | 64.29 |

| 13.4 We do not hold religious services/ceremonies/events/prayer at all. | 32.25 | 47.72 | 33.89 | 1.74 | 8.93 |

| N | 927 | 482 | 180 | 172 | 56 |

| By Region | By Religion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | MENA | Europe | Americas | Christian | Muslim | ||

| 19.1 We need to pray for the end of the coronavirus pandemic | |||||||

| 5 = strongly agree | 67.24 | 42.98 | 29.21 | 47.89 | 55.70 | 58.42 | |

| 4 = agree | 15.53 | 35.32 | 36.14 | 29.58 | 24.50 | 23.47 | |

| 3 = undecided | 6.37 | 11.06 | 13.86 | 7.04 | 6.98 | 8.16 | |

| 2 = disagree | 3.11 | 6.38 | 12.87 | 4.23 | 4.99 | 4.85 | |

| 1 = strongly disagree | 7.76 | 4.26 | 7.92 | 11.27 | 7.83 | 5.10 | |

| Mean | 4.31 | 4.06 | 3.66 | 3.99 | 4.15 | 4.25 | |

| SD | 1.21 | 1.09 | 1.24 | 1.33 | 1.23 | 1.12 | |

| N | 644 | 235 | 202 | 71 | 702 | 392 | |

| 19.2 My government is handling the coronavirus pandemic well | |||||||

| 5 = strongly agree | 12.89 | 15.38 | 23.08 | 11.11 | 16.57 | 12.56 | |

| 4 = agree | 21.58 | 27.35 | 52.88 | 27.78 | 29.32 | 25.38 | |

| 3 = undecided | 19.57 | 13.25 | 10.1 | 13.89 | 14.59 | 19.23 | |

| 2 = disagree | 26.4 | 30.77 | 9.13 | 19.44 | 24.65 | 24.10 | |

| 1 = strongly disagree | 19.57 | 13.25 | 4.81 | 27.78 | 14.87 | 18.72 | |

| Mean | 2.82 | 3.01 | 3.8 | 2.75 | 3.08 | 2.89 | |

| SD | 1.32 | 1.32 | 1.05 | 1.41 | 1.34 | 1.32 | |

| N | 644 | 234 | 208 | 72 | 706 | 390 | |

| 19.3 The measures taken by the government are increasing the gap between rich and poor | |||||||

| 5 = strongly agree | 26.45 | 30.04 | 12.08 | 35.14 | 25.64 | 25.45 | |

| 4 = agree | 31.3 | 36.48 | 38.65 | 24.32 | 32.05 | 34.96 | |

| 3 = undecided | 20.5 | 16.74 | 24.15 | 16.22 | 19.23 | 20.05 | |

| 2 = disagree | 12.21 | 10.73 | 20.29 | 13.51 | 14.39 | 12.08 | |

| 1 = strongly disagree | 9.55 | 6.01 | 4.83 | 10.81 | 8.69 | 7.46 | |

| Mean | 3.53 | 3.74 | 3.33 | 3.59 | 3.52 | 3.59 | |

| SD | 1.26 | 1.17 | 1.08 | 1.37 | 1.25 | 1.2 | |

| N | 639 | 233 | 207 | 74 | 702 | 389 | |

| 19.4 Domestic violence has increased during the coronavirus pandemic | |||||||

| 5 = strongly agree | 19.25 | 27.08 | 27.14 | 42.86 | 26.06 | 19.58 | |

| 4 = agree | 29.81 | 27.6 | 48.57 | 33.33 | 30.05 | 31.93 | |

| 3 = undecided | 22.98 | 20.83 | 15.71 | 17.46 | 19.72 | 23.49 | |

| 2 = disagree | 21.33 | 18.75 | 8.57 | 3.17 | 18.54 | 18.98 | |

| 1 = strongly disagree | 6.63 | 5.73 | 0 | 3.17 | 5.63 | 6.02 | |

| Mean | 3.34 | 3.52 | 3.94 | 4.1 | 3.52 | 3.4 | |

| SD | 1.2 | 1.23 | 0.88 | 1.01 | 1.22 | 1.17 | |

| N | 483 | 192 | 70 | 63 | 426 | 332 | |

| 19.5 The people in my community expect support during the times of the coronavirus from religious leaders | |||||||

| 5 = strongly agree | 35.57 | 25.65 | 18.05 | 50.68 | 35.70 | 25.65 | |

| 4 = agree | 31.98 | 36.09 | 51.71 | 32.88 | 36.42 | 36.01 | |

| 3 = undecided | 14.51 | 17.83 | 18.54 | 12.33 | 13.94 | 16.84 | |

| 2 = disagree | 12.17 | 15.22 | 9.27 | 4.11 | 9.39 | 16.06 | |

| 1 = strongly disagree | 5.77 | 5.22 | 2.44 | 0 | 4.55 | 5.44 | |

| Mean | 3.79 | 3.62 | 3.74 | 4.3 | 3.89 | 3.6 | |

| SD | 1.21 | 1.17 | 0.94 | 0.84 | 1.13 | 1.18 | |

| N | 641 | 230 | 205 | 73 | 703 | 386 | |

| 19.6 Other religious communities have given their members the right advice with regard to the coronavirus | |||||||

| 5 = strongly agree | 22.14 | 17.83 | 6.83 | 8.11 | 18.48 | 17.88 | |

| 4 = agree | 33.59 | 33.04 | 36.59 | 36.49 | 33.00 | 36.53 | |

| 3 = undecided | 23.07 | 29.13 | 42.93 | 36.49 | 28.49 | 24.87 | |

| 2 = disagree | 15.17 | 13.91 | 11.71 | 16.22 | 14.67 | 15.54 | |

| 1 = strongly disagree | 6.04 | 6.09 | 1.95 | 2.7 | 5.36 | 5.18 | |

| Mean | 3.51 | 3.43 | 3.35 | 3.31 | 3.45 | 3.46 | |

| SD | 1.17 | 1.12 | 0.85 | 0.94 | 1.11 | 1.11 | |

| N | 646 | 230 | 205 | 74 | 709 | 386 | |

| 19.7 Most of the information on the coronavirus in the media in my country are reliable | |||||||

| 5 = strongly agree | 22.93 | 18.1 | 22.71 | 18.06 | 24.89 | 16.93 | |

| 4 = agree | 36.19 | 34.05 | 58.45 | 33.33 | 41.73 | 34.64 | |

| 3 = undecided | 17.78 | 19.4 | 13.04 | 16.67 | 14.57 | 20.05 | |

| 2 = disagree | 14.98 | 17.24 | 3.86 | 25 | 12.87 | 17.97 | |

| 1 = strongly disagree | 8.11 | 11.21 | 1.93 | 6.94 | 5.94 | 10.42 | |

| Mean | 3.51 | 3.31 | 3.96 | 3.31 | 3.67 | 3.3 | |

| SD | 1.22 | 1.26 | 0.83 | 1.23 | 1.16 | 1.24 | |

| N | 641 | 232 | 207 | 72 | 707 | 384 | |

| 19.8 Measures taken by my government are a necessary response to the coronavirus | |||||||

| 5 = strongly agree | 26.55 | 22.94 | 37.02 | 28.77 | 30.88 | 23.20 | |

| 4 = agree | 33.23 | 39.83 | 50.48 | 45.21 | 37.96 | 39.18 | |

| 3 = undecided | 15.37 | 13.85 | 6.73 | 12.33 | 12.32 | 14.95 | |

| 2 = disagree | 17.86 | 16.02 | 2.88 | 6.85 | 13.03 | 16.24 | |

| 1 = strongly disagree | 6.99 | 7.36 | 2.88 | 6.85 | 5.81 | 6.44 | |

| Mean | 3.55 | 3.55 | 4.16 | 3.82 | 3.75 | 3.56 | |

| SD | 1.25 | 1.21 | 0.89 | 1.13 | 1.19 | 1.19 | |

| N | 644 | 231 | 208 | 73 | 706 | 388 | |

| 19.9 The health care system in my country is able to handle the coronavirus pandemic well | |||||||

| 5 = strongly agree | 15.91 | 15.88 | 48.56 | 16.44 | 23.72 | 14.91 | |

| 4 = agree | 30.42 | 30.9 | 40.87 | 31.51 | 33.10 | 31.88 | |

| 3 = undecided | 22.31 | 19.31 | 5.29 | 12.33 | 16.34 | 21.34 | |

| 2 = disagree | 19.81 | 17.6 | 3.37 | 28.77 | 17.61 | 18.51 | |

| 1 = strongly disagree | 11.54 | 16.31 | 1.92 | 10.96 | 9.23 | 13.37 | |

| Mean | 3.19 | 3.12 | 4.31 | 3.14 | 3.44 | 3.16 | |

| SD | 1.25 | 1.33 | 0.87 | 1.31 | 1.28 | 1.27 | |

| N | 641 | 233 | 208 | 73 | 704 | 389 | |

| 19.10 The coronavirus is a divine punishment | |||||||

| 5 = strongly agree | 19.65 | 18.06 | 0.48 | 2.78 | 12.98 | 19.63 | |

| 4 = agree | 24.06 | 24.23 | 1.44 | 4.17 | 14.55 | 26.70 | |

| 3 = undecided | 19.81 | 18.06 | 5.77 | 8.33 | 13.69 | 21.47 | |

| 2 = disagree | 16.35 | 21.59 | 10.58 | 15.28 | 14.69 | 19.90 | |

| 1 = strongly disagree | 20.13 | 18.06 | 81.73 | 69.44 | 44.08 | 12.30 | |

| Mean | 3.07 | 3.03 | 1.28 | 1.56 | 2.38 | 3.21 | |

| SD | 1.41 | 1.38 | 0.68 | 1.01 | 1.48 | 1.3 | |

| N | 636 | 227 | 208 | 72 | 701 | 382 | |

| 19.11 Religious leaders should respond to the issue of domestic violence | |||||||

| 5 = strongly agree | 31.3 | 32.11 | 31.88 | 66.67 | 38.81 | 27.78 | |

| 4 = agree | 29.62 | 33.68 | 55.07 | 23.33 | 31.19 | 33.64 | |

| 3 = undecided | 14.08 | 15.26 | 11.59 | 1.67 | 11.43 | 15.43 | |

| 2 = disagree | 16.6 | 12.11 | 1.45 | 6.67 | 12.62 | 15.74 | |

| 1 = strongly disagree | 8.4 | 6.84 | 0 | 1.67 | 5.95 | 7.41 | |

| Mean | 3.59 | 3.72 | 4.17 | 4.47 | 3.84 | 3.59 | |

| SD | 1.31 | 1.23 | 0.69 | 0.95 | 1.23 | 1.25 | |

| N | 476 | 190 | 69 | 60 | 420 | 324 | |

| 19.12 Environmental destruction is of greater concern than the coronavirus | |||||||

| 5 = strongly agree | 20.4 | 22.08 | 18.84 | 19.18 | 19.86 | 19.38 | |

| 4 = agree | 28.35 | 37.23 | 39.61 | 27.4 | 28.23 | 37.98 | |

| 3 = undecided | 18.69 | 20.78 | 29.47 | 27.4 | 21.84 | 19.90 | |

| 2 = disagree | 20.87 | 15.58 | 8.21 | 19.18 | 19.43 | 15.76 | |

| 1 = strongly disagree | 11.68 | 4.33 | 3.86 | 6.85 | 10.64 | 6.98 | |

| Mean | 3.25 | 3.57 | 3.61 | 3.33 | 3.27 | 3.47 | |

| SD | 1.31 | 1.12 | 1.01 | 1.19 | 1.27 | 1.17 | |

| N | 642 | 231 | 207 | 73 | 705 | 387 | |

| By Region | By Religion | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | MENA | Europe | Americas | Christian | Muslim | ||

| 20.1 Reduce inequalities between rich and poor | |||||||

| 5 = extremely important | 41.59 | 37.50 | 56.25 | 73.97 | 51.49 | 32.13 | |

| 4 = quite important | 17.91 | 26.72 | 34.62 | 16.44 | 20.85 | 25.45 | |

| 3 = moderately important | 10.75 | 16.38 | 5.77 | 4.11 | 8.23 | 14.14 | |

| 2 = not very important | 12.15 | 10.78 | 1.92 | 1.37 | 8.37 | 12.85 | |

| 1 = not important at all | 17.6 | 8.62 | 1.44 | 4.11 | 11.06 | 15.42 | |

| Mean | 3.54 | 3.74 | 4.42 | 4.55 | 3.93 | 3.46 | |

| SD | 1.54 | 1.30 | 0.81 | 0.96 | 1.39 | 1.44 | |

| N | 642 | 232 | 208 | 73 | 705 | 389 | |

| 20.2 Increase international cooperation | |||||||

| 5 = extremely important | 37.81 | 41.56 | 41.06 | 58.90 | 43.00 | 34.11 | |

| 4 = quite important | 28.75 | 25.54 | 40.10 | 27.40 | 31.26 | 26.56 | |

| 3 = moderately important | 11.09 | 15.15 | 13.04 | 8.22 | 10.18 | 15.10 | |

| 2 = not very important | 15.00 | 10.39 | 4.35 | 4.11 | 10.18 | 16.41 | |

| 1 = not important at all | 7.34 | 7.36 | 1.45 | 1.37 | 5.37 | 7.81 | |

| Mean | 3.75 | 3.84 | 4.15 | 4.38 | 3.96 | 3.63 | |

| SD | 1.3 | 1.27 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 1.19 | 1.31 | |

| N | 640 | 231 | 207 | 73 | 707 | 384 | |

| 20.3 Reduce globalization | |||||||

| 5 = extremely important | 19.81 | 24.77 | 6.83 | 16.18 | 16.86 | 21.90 | |

| 4 = quite important | 19.34 | 25.23 | 18.54 | 20.59 | 18.44 | 24.80 | |

| 3 = moderately important | 20.91 | 22.07 | 32.68 | 26.47 | 25.22 | 19.00 | |

| 2 = not very important | 23.11 | 17.12 | 30.24 | 22.06 | 24.21 | 21.11 | |

| 1 = not important at all | 16.82 | 10.81 | 11.71 | 14.71 | 15.27 | 13.19 | |

| Mean | 3.02 | 3.36 | 2.79 | 3.01 | 2.97 | 3.21 | |

| SD | 1.38 | 1.31 | 1.09 | 1.3 | 1.31 | 1.35 | |

| N | 636 | 222 | 205 | 68 | 694 | 379 | |

| 20.4 Strengthen national borders | |||||||

| 5 = extremely important | 28.08 | 26.82 | 1.46 | 10.00 | 21.41 | 24.80 | |

| 4 = quite important | 26.34 | 25.00 | 6.31 | 14.29 | 18.97 | 27.20 | |

| 3 = moderately important | 18.61 | 26.82 | 9.22 | 21.43 | 17.39 | 22.67 | |

| 2 = not very important | 14.51 | 14.09 | 34.95 | 24.29 | 20.40 | 15.47 | |

| 1 = not important at all | 12.46 | 7.27 | 48.06 | 30.00 | 21.84 | 9.87 | |

| Mean | 3.43 | 3.50 | 1.78 | 2.50 | 2.98 | 3.42 | |

| SD | 1.36 | 1.23 | 0.96 | 1.33 | 1.46 | 1.28 | |

| N | 634 | 220 | 206 | 70 | 696 | 375 | |

| 20.5 Substantially change the way the economy works | |||||||

| 5 = extremely important | 33.28 | 41.56 | 35.78 | 55.56 | 36.51 | 33.94 | |

| 4 = quite important | 23.66 | 24.24 | 39.22 | 22.22 | 27.56 | 23.32 | |

| 3 = moderately important | 15.93 | 15.58 | 18.63 | 13.89 | 15.87 | 18.39 | |

| 2 = not very important | 16.72 | 12.12 | 3.43 | 4.17 | 11.11 | 16.58 | |

| 1 = not important at all | 10.41 | 6.49 | 2.94 | 4.17 | 8.95 | 7.77 | |

| Mean | 3.53 | 3.82 | 4.01 | 4.21 | 3.72 | 3.59 | |

| SD | 1.37 | 1.27 | 0.97 | 1.1 | 1.30 | 1.31 | |

| N | 634 | 231 | 204 | 72 | 693 | 386 | |

| 20.6 Strengthen environmental protection | |||||||

| 5 = extremely important | 37.13 | 47.62 | 64.9 | 73.97 | 50.57 | 36.79 | |

| 4 = quite important | 20.59 | 18.61 | 25.48 | 16.44 | 21.53 | 19.43 | |

| 3 = moderately important | 16.07 | 16.45 | 4.33 | 4.11 | 9.92 | 19.95 | |

| 2 = not very important | 15.6 | 12.55 | 2.88 | 1.37 | 9.77 | 15.80 | |

| 1 = not important at all | 10.61 | 4.76 | 2.40 | 4.11 | 8.22 | 8.03 | |

| Mean | 3.58 | 3.92 | 4.48 | 4.55 | 3.96 | 3.61 | |

| SD | 1.39 | 1.25 | 0.90 | 0.96 | 1.32 | 1.33 | |

| N | 641 | 231 | 208 | 73 | 706 | 386 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Öhlmann, P.; Sonntag, E.A. The Religious Leaders’ Perspectives on Corona Survey: Methods and Key Results. Religions 2024, 15, 1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121474

Öhlmann P, Sonntag EA. The Religious Leaders’ Perspectives on Corona Survey: Methods and Key Results. Religions. 2024; 15(12):1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121474

Chicago/Turabian StyleÖhlmann, Philipp, and Ekkardt A. Sonntag. 2024. "The Religious Leaders’ Perspectives on Corona Survey: Methods and Key Results" Religions 15, no. 12: 1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121474

APA StyleÖhlmann, P., & Sonntag, E. A. (2024). The Religious Leaders’ Perspectives on Corona Survey: Methods and Key Results. Religions, 15(12), 1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15121474