Abstract

The “Zhenshan” 鎮山 (which means a mountain that guards a certain territory) system is based on the traditional Chinese view of nature, which formed and developed through a long period of Confucian humanistic construction. It is the typical representation of China’s nature-oriented worship space, and it has unique spatial order and spatial significance in the world’s sacred mountain worship. The excavation of the spatial characteristics of Zhenshan worship and its network of humanistic meanings is an important part of research that aims to discover the traditional Chinese values of nature, religious views, and Chinese worship space. Based on the analysis of graphic historical materials and a digital chronicle literature review, this paper quantitatively analyzes the historical information of Zhenshan and summarizes the process of change from the birth of the concept of Zhenshan in the Zhou dynasty to the formation of the sacrificial system in the Han dynasty and its gradual localization after the Tang and Song dynasties with an analysis of its spatial pattern and characteristics of worship. The results show that Zhenshan is one of the typical cultural symbols of the transformation of Chinese mountain worship into the unity of government and religion. And it is a typical product of Confucianism, in which the worship of nature in China is integrated into the political system, and its worship space is rooted in the national, regional, and urban spaces at multiple levels. The Zhenshan system, in the course of its dynamic development, has formed two types of worship space: temple sacrificial and metaphorical constraint, constructing a Chinese worship space based on the order of nature, which is distinctly different from the inward-looking religious space of the West and the sacred mountain worship space formed around the religion of the “supreme god”.

1. Introduction

The veneration of nature is the most ancient kind of religious awareness among humans, and nearly all religious doctrines are connected to it, making it a fundamental origin of religious development. Feuerbach remarked that “nature is the initial and most primitive object of religion, which is fully proven by the history of all religions and ethnic groups” (Feuerbach 1959). When confronted with incomprehensible natural phenomena, humanity can only venerate them by attributing them to divine qualities. The worship of nature and the belief in nature were prevalent in the beginning stages of the cultural creation of all peoples of the world. In any religion, some places are viewed as particularly favorable for establishing contact with supernatural powers (Naquin and Yu 1992). The worship of mountains is one of the most fundamental and common varieties (Wang 2004).

The natural characteristics of mountains are the objective basis for the association of divinity. In the primitive stage, various ethnic groups around the world generally regarded mountains as sacred themselves or as intermediaries for consecration, using non-logical thinking to achieve an understanding of divine intentions and endowing them with the “supreme” sacredness. Religious historian Mircha Iliad summarized the reasons for the sanctity of mountains: firstly, it stems from the transcendent symbolic space generated by altitude, which corresponds to “towering” and “supreme”; the second reason is that natural weather conditions such as thunderstorms, clouds, and rain formed by the high-altitude climate were regarded by the ancestors as signs of divine intervention, so they also regarded the mountains as the dwelling places of gods (Eliade and Yan 2008). In the West, Mount Olympus, the highest mountain in Greece, was believed by the Greek ancestors to be located in the center of Greece and the center of the Earth. It was the place where the Greek god Zeus and the gods lived and ruled over all things in Greek mythology (Burkhart 2008). In Balinese mythology, the gods use mountains as their divine seats. Balinese people consider Mount Agon to be the “center of the world”. In the Bible, the high places are referred to as “bamot” in Hebrew, which refers to places marked by altars, stone tablets, or wooden pillars, indicating a close connection between high mountains and activities such as divine worship. In the Chinese Book of Rites—Sacrificial Rites 《禮記·祭法》, it is said that “mountains, forests, rivers, valleys, and hills can produce clouds, which is called wind and rain. When monsters are seen, they are all called gods”, “山林川穀丘陵,能出雲,為風雨,見怪物,皆曰神”. In mythology, Kunlun Mountain 昆侖山 “corresponds to the sky and is most centered”, “應於天,最居中”, and as the dwelling place of a hundred gods, it is “the root of heaven and earth, the handle of ten thousand degrees”, “天地之根紐,萬度之綱柄”. At the same time, the Yellow River and Yangtze River basins, the birthplace of Chinese civilization, are based on agricultural civilization. China’s natural worship has a strong agricultural expectation. The Erya Commentary《爾雅注疏》explains this expectation as “Mountain, production”, “山,產也”. Therefore, Chinese ancestors worshipped mountains even more due to their abundant natural resources and control over the weather.

As society has progressed, sacred mountains have increasingly intertwined with politics and religion, becoming revered locations that serve as the focal point of worship. The sacredness of natural mountains in mainstream religions such as Christianity and Islam is mostly attributed to the lives and journeys of God and saints. Within the Hebrew Bible, sacred locations are classified into two distinct categories: (1) where God lives; and (2) the holy place where God came to Earth. There are four prominent holy mountains in the Jewish Christian region of the Middle East: Ararat is located in eastern Turkey and is traditionally believed to be the landing site of Noah’s Ark. Mount Moses, located in the Sinai Peninsula, served as the elevated summit where Moses received the Ten Commandments. Mount Zion in Israel is the place where God created the world. The temple was built on this mountain, thus making Mount Zion an important cosmic mountain (Zhang 2016). Mount Tabor in Israel is the site of Jesus’ Transfiguration. The sanctity of all four mountain ranges is associated with God. Western faiths are often linked to ethnic, political, and power conflicts. In addition, several sacred mountains also function as strongholds of spiritual devotion, national awareness, territorial consciousness, and identity affirmation. For instance, many religious groups frequently assert their territorial authority and cultural superiority by demolishing and reconstructing temples, using Mount Zion as a symbolic representation of the ever-evolving political environment in the Middle East. Nevertheless, throughout the later evolution of religious beliefs, mountains did not assume the role of being worshipped, with God remaining the exclusive object of adoration. Early Christians had the freedom to worship God in various locations, including fields, underground tombs, riverbanks, and residences. Mountains have ceased to serve as a medium for sacred spaces due to the progress and transformations that have taken place. The determination of sacrifice rituals has led to the establishment of six ritual elements in Christianity, including gatherings, activities, congregations, choirs, baptisms, and sacrificial tables. Architecture offers a superior spatial setting for worship, with the church being the paramount venue for religious worship. The church did not combine with the mountain to form a fixed spatial paradigm for worship. In Islam, mountains serve as a platform for comprehending the divine intention of Allah or God. The Mount of Mercy in Mecca is currently regarded as a sacred location by followers of Islam, as it is the site where Muhammad delivered his final sermon (Bernbaum 1997). The prophet Muhammad sought spiritual solace in the caves of Mount Hira and received a revelation from God, the Qur’an, delivered by the angel Gabriel on the Night of Glory. However, Islam does not treat mountains as objects and places of worship. Its primary worship space is a mosque, constructed in highly populated and heavily trafficked regions. The construction direction of these buildings is determined only by religious principles, rather than being influenced by geography or the calendar. It is designed to have a unified architectural orientation, facing toward the holy land of Islam—Mecca. Thus, it may be inferred that these sacred mountains, which have strong connections to established beliefs, have served to reinforce belief and foster unity among followers (Du and Han 2019), but have not evolved into objects of veneration or sites of worship.

However, as early as the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, Chinese religion had already eliminated the pure “divine rule” and focused on human affairs. Undoubtedly, the sacred and worship spaces of Buddhist and Taoist holy mountains in China are mostly formed by the worship of religious saints and relics, forming holy sites. However, in specific contexts, the significance of mainstream religious mountains in China is mostly dominated by humanities, rather than relying solely on the derivation of Buddhism and Taoism (Du and Han 2019). In China, the idea of sacred mountains goes back to the dawn of history, long before the introduction of Buddhism and the emergence of religious Taoism (Naquin and Yu 1992). In worship space with mountains as the main body, the Zhenshan system, which is dominated by Confucianism, the third largest traditional Chinese religion, is a unique cultural phenomenon in China’s traditional worship space, with special cultural roots, spatial order, and spatial significance, and thus is more representative of China’s worship space. Gu Hongming 辜鴻銘 once mentioned the difference between Confucianism, Christianity, and Buddhism: Christianity and Buddhism are human religions or church religions, while Confucianism is a social or national religion. The true greatness of Confucianism lies in giving people the correct national philosophy and elevating this philosophy into a religion. Therefore, in terms of the social functions it creates, Confucianism is the same as religion, no different from Christianity and Buddhism, and can be regarded as a broad religion (Gu 2018). The Zhenshan system, constructed through Confucianism and based on the traditional Chinese view of nature, has had a more far-reaching influence on the construction of the Chinese belief system, the geospatial system of the land, and even the urban and rural spatial system in the course of China’s long-term historical development. The Zhenshan system is an indispensable research content in the study of Chinese worship space, and an important breakthrough in exploring the deep cultural connotations of traditional Chinese natural views, religious concepts, and educational methods. Based on the uniqueness of Zhenshan in the world’s worship space and its representativeness in China’s worship space, this article summarizes the spatial characteristics and significance of Zhenshan worship in the light of the formation and change process of the Zhenshan system. Moreover, this paper summarizes the process of the formation of the uniqueness of Zhenshan in the process of cultural construction.

2. The Foundation of the Formation of Zhenshan—The Continuation of Natural Divinity

In primitive societies, nature worship was prevalent in various civilizations around the world. However, after the end of primitive society, nature worship underwent completely different changes in the process of the development of Chinese and Western civilizations; however, the divinity of nature continued in China. In contrast, the divinity of nature in the West disappeared with the birth of religion. This is the fundamental reason for the special nature of Chinese mountain worship.

There are different paths of rational transformation of the supreme god in Chinese and Western religions, which is the direct reason for the differentiated development of nature worship in China and the West. After experiencing rational thinking, Western nature underwent a separation of gods and objects, dividing nature into mechanical nature (non-humanistic nature in the eyes of Greeks) and natural gods. At the same time, the heroes of the human world combined with the natural gods to ascend to the upper realm to form the supreme God, constructing a creation myth in which God creates, delivers, and governs all things in the world, and a religious transcendence exists between God and humankind (Wu 2004). And God granted humans the right to govern all things in nature, thus forming anthropocentrism and influencing the relationship between humans and nature. As Joseph Needham pointed out, Western thought swings between two worlds in dealing with the issue of nature: one is the world seen as an automaton, which is a silent world, a rigid and passive nature, and its behavior is like an automaton. Once it is programmed, it runs continuously according to the rules described in the program, and in this sense, humans are isolated from nature; another is that God governs the theological world of the universe, and nature operates according to God’s will (Needham 1975). Therefore, in the rational transformation process of nature worship, nature has lost its primitive divinity in Western philosophical concepts. The reason there are still holy mountains and holy realms is that they are associated with the divinity of the supreme God. Mountains are just special places for believers to commemorate and worship God, with a mysterious environment and a noble atmosphere.

Compared with Western culture, ancient China lacked a creation myth that could support a fixed image as the supreme god, and the spiritual theme was also dedication rather than redemption. The gods in creation myths ultimately belonged to nature. The supreme deity in China is based on the comprehension of nature and the universe (Wang 2002). Unlike the concept of “God” in the West, at least from as early as the Xia, Yin, and Zhou dynasties, Chinese rulers believed that they received a mandate from heaven天 to rule over the world (Sun and Kistemaker 1997). China’s “heaven”天 is “unknown, unknown to people”, “inclusive of everything, and interconnected by rules”, “無聲無臭”, “無容無則”, emphasizing more the power and laws of nature rather than absolute religious deities. China’s gods and humans are a unified but loose relationship. The supreme deity in China is not elevated to the realm of gods and then looks down on the human world, but infiltrates into nature and the human world, that is, the unity tendency of the fusion of ontology and phenomena, the upper and lower realms (Zou 1999). The deity lies in nature, and it can also be said that the deity is nature. Calling nature a deity gives one a sense of kinship and a sense of being with nature (Hu 2013). Therefore, China’s natural worship continues and shows a tendency toward worshipping pan-natural deities. Mountains are one of the more prominent types of worship, continuing and developing from the primitive ideas of mountain worship, forming a rational natural worship activity for mountains and mountain deities. The worship space it forms revolves around the reverence, gratitude, and worship of the mountain itself, which has fundamentally differed from the worship space of Western holy mountains.

Sacrifice 祭祀 is the study of the principles of things 格物 and realization and gratitude toward nature (Hu 2013), and the continuation of sacrificial activities is the main manifestation of the continuation of natural divinity. The development of mountain worship in ancient China has never ceased, and through sacrificial activities, the spiritual relationship between humans and gods, as well as between humans and nature has deepened. In China, superhuman, conscious, and personalized mountain deities emerged in the later stages of primitive society. In the face of incomprehensible and irresistible natural phenomena and disasters, the ancestors personified these phenomena and offered sacrifices in exchange for the help of gods. With the development of tribal alliance social forms, their sacrificial goals gradually shifted from agricultural production needs, such as seeking rain and harvest, to social goals, such as treating diseases, judging between right and wrong, and punishing evil. The gods of mountains also transformed from natural gods to clan or tribal leaders, gradually combining ancestor gods with mountain deities. This is a manifestation of the Chinese concept of nature’s affinity with nature, laying the foundation for the deepening development of Chinese mountain worship toward social functions.

3. The Formation and Evolution of the Zhenshan Worship System

3.1. The Birth of Zhenshan—The Integration of Mountain Worship and Politics

After the end of primitive society, China’s ancestors led the worship of mountains. However, mountain worship not only lies in the worship of the natural divinity of the mountains; with the development of society, the worship of mountains and politics gradually united, thus extending to the worship of the political and humanistic significance of mountains. The combination of mountain worship and politics is highlighted by the following three points: first, the continuous combination of mountain worship and political legitimacy; second, mountains became imagery and symbols of territories and states; and third, mountains gradually became a tool for constructing and strengthening the political order. The formal combination of mountain worship and politics eventually led to the birth of the concept of Zhenshan.

The combination of mountain worship and political legitimacy began during the tribal alliance period and was ultimately established as the mountain became a place to offer sacrifices to heaven. The changes in the subject of natural sacrificial activities had a significant impact on the origin of the ancient Chinese monarchy (Liao 2008). In the process of evolving toward early states, the upper echelons of the tribe gradually seized the public power of worship, which connected the heavens and gods. The transfer of power from witchcraft to tribal leaders resulted in the institutionalization and normalization of worship. As early civilizations developed, tribal leaders were replaced by monarchs, who made sacrificial offerings a privilege of the monarchy, elevating them to significant events for the country. The earliest mountain and river sacrificial activities with national significance are recorded in Shang Shu, “Shun Dian” 《尚書 舜典》 (Wang 2018). The text describes how Shun 舜 accepted Yao’s 堯 abdication edict and reported to heaven to demonstrate that he had obtained the highest authority and that performing mountain sacrifices was an important part of this authority. It can be seen that as early as the period of tribal alliances, mountain sacrifices were already associated with the legitimacy of the regime. During the Shang 商 dynasty, mountain sacrifice became a common political ritual. There were two types of mountain worship rituals: Ji 即 (personally going to worship) and Wang 望 (looking from afar to worship). Ji was a mountain sacrifice ritual presided over by the monarch. Oracle bone inscriptions verify that the sacrificial rituals often corresponded to Hua 華 and Yue 嶽, with “Yue” being the most commonly worshipped. Some scholars believe that the term Yue refers to a general large mountain, while others believe it refers to a specific mountain, such as Tai Yue Mountain (also known as Hua Mountain or Tai Mountain), Song Mountain 嵩山, Hua Mountain 華山, etc. (Wang 2022). During the Shang dynasty, Hua, Yue, and other mountains were selected as national mountain sacrificial sites for the monarch to preside over.

In the Xia and Shang dynasties, with the emergence of the concept of “heaven” 天, high mountains were closest to the “material heaven”, and the concept of “heaven” was formed with the help of the concept of “mountain”, just as “The high mountains are where all things were created by the heavens”, “天作高山”. In the Xia dynasty, with the deepening of the “Material Heaven” into the “Ruling Heaven and Destiny Heaven” (Wang 1999), the position of the “Heavenly Emperor” as the supreme god was gradually established. The Zuo Zhuan 《左傳》 (Zuo n.d.) states that “Yu and his lords gathered at Tu Mountain with jade and silk from all nations”, “禹合諸侯於塗山,執玉帛者萬國”. Specific mountains gradually became places where rulers sacrificed to the heavens. Until the Zhou dynasty, the consciousness of “royal power bestowed by heaven” was officially established, and the Chinese civilization’s concept of destiny gradually entered a period of depersonalization of the heavenly Dao 天道. The heavenly world and the human world were gradually differentiated, and in this process of differentiation, the figurations of the heavenly world appeared in the image of Zhou Tianzi 周天子. The monarch combines religious and political power. Religious worship based on nature worship gradually became a tool for maintaining royal rule, eventually negating the possibility of divine power politics that emerged in the Zhou dynasty and later generations (Zhang 1994). The highest mountain in the territory is regarded as the best medium for reaching heaven and Earth and officially becomes a place of “heaven” sacrifices. It is a symbol of the complete transformation of mountain worship from natural attributes to social attributes, and also the main reason mountains have symbolic significance for political legitimacy. The sacrificial activities in the mountains further highlight the close relationship between the Zhou emperor and the heavens. The Zhou emperor sought to use mountain worship to demonstrate his unique power as an emperor, to ingrain the idea of divine authority in the hearts of the people, and to demonstrate the legitimacy of the ruling power bestowed on humankind by heaven through the medium of the mountains. This also led to the establishment of a ceremony that carried on the mandate of heaven and followed the will of the people, known as “ascending to Heaven through famous mountains”, “因天事天,因地事地,因名山升中於天”. Although the term “Fengshan” 封禪 had not yet been coined in the Zhou dynasty, activities with the same purpose and connotation had already emerged, and mountain sacrifice continued into later generations, becoming the most important form of heavenly sacrifice. Emperor Zhou’s “Fengchan” activity was mainly carried out on Mount Taishan and Mount Song, and with the gradual strengthening of the awareness of “mountains and rivers ruling the country” 國主山川 and the connection between heaven and humankind, mountains as a geographical phenomenon in people’s perception became linked to national destiny. Thus, mountains became a clear symbol of national stability in people’s minds.

The association of mountains with territorial and national imagery stems from the combination of the geographical perception of mountains and rivers with the feudal system. It is common, indeed rational, to think of mountains as symbols of stability (Robson 2009). The ancient people’s understanding of China’s geographical space was shaped by the mountains, and before the formation of class society in China, due to the flooding of rivers, the ancient people often lived on small islands called “states” 州. The Shang Shu, “Shun Dian” 《尚書-舜典》 (Wang 2018), states that “there were originally twelve states, among which twelve mountains were worshipped”, “肇十有二州,封十有二山”, with high mountains as the symbol of the twelve states. In the era of Xia 夏, under the guidance of the establishment of the national system and the political consciousness of national unity, the country’s borders were further integrated, and the “Twelve States and Twelve Mountains” 十二州十二山 became the “Nine States and Nine Mountains” 九州九山. In the Shang Shu, “Yu Gong” 《尚書-禹貢》 (Wang 2018), it is stated that “Yu separates the boundaries of the land, walks high mountains and cuts down trees as signposts, and lays down boundaries with high mountains and big rivers”, “(禹)敷土,隨山刊木,奠高山大川”. During the process of water control, Yu 禹 measured the entire geography of the country, worshipped mountains and rivers, and delineated boundaries. During the Tang dynasty, Cai Shen 蔡沈 said, “The high mountains and rivers within a certain geographical boundary provide a coordinate system for people to use as a natural boundary for regional division”, forming a concise and clear geographical spatial pattern for complex geographical situations. In addition, the “Yu Gong” in the Shang Shu 《尚書-禹貢》 (Wang 2018) states that “the Nine States were unified as a result...all nine mountain ranges were now accessible through logging and road construction”, “九州攸同......九山刊旅”. The connotation of the mountains and geographical territories also formed a further combination, reflecting the symbolic significance of the Nine Mountains and the unity of territory and country.

The establishment of the Nine Mountains in nine states reflects the differentiation of the status of the Nine Mountains and other mountains and determines the political hierarchy of the mountains with the final establishment of the patriarchal system. As early as the Yu and Shun periods, the Shang Shu, “Shun Dian” 《尚書-舜典》 (Wang 2018), states that Shun arrived at Mount Tai and held chai sacrifices, “至於岱宗,柴,望秩於山川”, reflecting the political status of Mount Tai above other mountains. For other mountains, sacrifices were held according to their status, which is the germ of the hierarchical order of mountain sacrifices. In the Shang dynasty, the division of the two kinds of mountain sacrifice methods, namely “Ji” 即 and “Wang” 望, also further promoted the hierarchical differentiation of mountains; moreover, “Hua” 華 and “Yue” 嶽 in ritual practices, and also as the objects of sacrifice, such as the Ten Mountains, Nine Mountains, Five Mountains, Three Mountains, and Two Mountains, were different from other mountains in the geography.

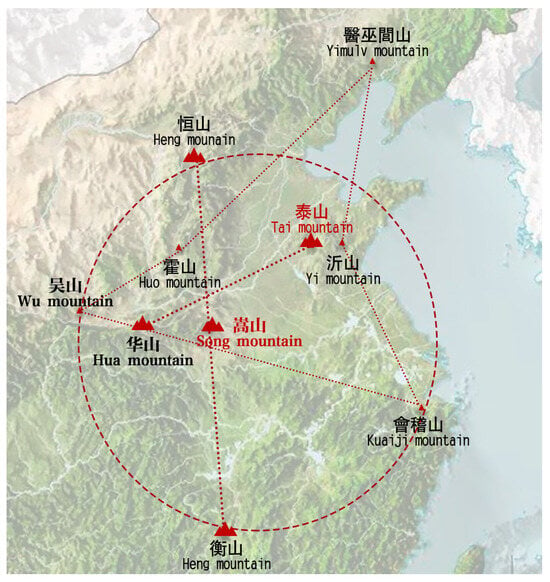

The Zhou dynasty built a patriarchal system with the emperor of Zhou as the patriarch, and mountain sacrifice was also an important means of maintaining the patriarchal system, which led to the integration of national famous mountains in geographical space, formed the attachment of famous mountain hierarchy to territorial symbolic significance, and built a sacrificial system dominated by the patriarchal sacrificial system. The emperor of the Zhou dynasty was at the first level, while the princes were at the second level. The emperor could offer sacrifices to famous mountains all over the world, while the princes could only offer sacrifices to the mountains in their fiefs, so the mountains in each fief gradually became the symbol of the fiefs. Under the influence of the idea of great unity, the Rites of Zhou, “Zhi Fang Shi” 《周禮·職方氏》 (Zheng 2010), further identified the respective mountains of nine states, namely Kuaiji Mountain in Yangzhou 揚州會稽山, Hengshan in Jingzhou 荊州衡山, Huashan in Yuzhou 豫州華山, Yishan in Qingzhou 青州沂山, Daishan in Yanzhou 兗州岱山, Yueshan in Yongzhou 雍州嶽山, Yiwulu in Youzhou 幽州醫巫閭, Huoshan in Jizhou 冀州霍山, and Hengshan in Bingzhou 並州恒山. At the same time, in order to demonstrate that they owned the lands of the nation and consolidate their rule, the rulers hunted around, made symbolic sacrifices to the famous mountains of various princes, constantly affirmed and reaffirmed the privileges of the king, affirmed that the king was the hub of the unity of heaven and humankind, and took the mountain as the geographical and cultural symbol to control the princes. Therefore, the mountains in each state were also called “Zhen” 鎮, and the concept of “Zhenshan” 鎮山 was born. The Shuowen 《說文》 states that “Zhen, to exert pressure”, “鎮,博壓也”. The original meaning is to exert pressure on an object, which can be extended to mean suppression, restriction by force, and subduction. The Guangya 《廣雅》 states that “Zhen, stable”, “鎮,安也”, meaning stability and comfort. In the Records of the Grand Historian (Sima 2019), the declaration “To govern the country and pacify the people”, “鎮國家,撫百姓”, is made. Therefore, stability is the intention of “Zhen” 鎮 and deterrence is the means of “Zhen” 鎮. With “Zhen” 鎮 as a vivid verb, the dual humanistic connotation of integrating civil and military elements is explained. The word “Zhenshan” 鎮山 was used to refer to the mountains in each state, and the corresponding Zhenshan sacrificial system was established, which put forward the political intention of the mountains to deter and stabilize one side. At the same time, the Nine Zhenshan of the nine states combined together is no longer a purely natural geographical concept, but also a grand and well-conceived program of political geography, reflecting the high degree of “great unity” of the cultural identity of the national political and cultural order of the “six contractual winds, the common thread of the nine states”, “六合同風,九州共貫”, which the people of that time were seeking. Thus, Zhenshan is a typical symbol of the complete transformation of the natural attributes of mountain worship into social attributes.

3.2. Construction of the National Mountain Sacrifice System—Establishment of Political Order in the Mountain Geographical Space

Based on the Zhou dynasty’s philosophy of governance, Confucianism upholds the concept of the unity of politics and indoctrination and uses politics to unify indoctrination and indoctrination to promote politics. Furthermore, Confucianism did not abandon and scorn the role of indoctrination by making politics extremely legalistic and instrumental, as Legalism did, nor did it give indoctrination a strong religious flavor, as Taoism and Buddhism did, while remaining indifferent to politics (Jin 2017). The political significance symbolized by mountain sacrifices in Chinese feudal society has always been the basis for guiding national policies and promoting politics. Since the Qin and Han dynasties, China’s mountain sacrifice rituals have been closely integrated with national laws and regulations. The mountain sacrifice system has become an important part of the religious and spiritual life of China’s feudal society and has been passed down throughout feudal society. At the same time, through the establishment of the national mountain sacrifice system, the geographical and political order of the country’s territory and mountains was established, and concepts such as “middle” were continuously consolidated, thereby strengthening the unity of political thought and social education.

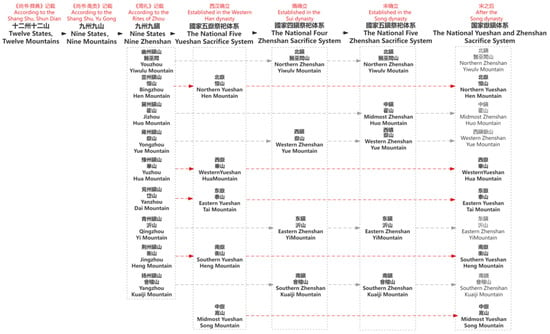

The “Nine States and Nine Zhenshan” identified by Zhenshan in the Rites of Zhou laid the foundation for the establishment of the national sacrificial ritual system in later times. Emperor Qin Shi Huang of the Qin dynasty combined the famous mountains handed down from ancient times to the Zhou dynasty with the various mountains in the “Yong” region 雍地 to form first-class mountains and established the twelve famous mountain worship system of the seven famous mountains in Guanzhong and the five famous mountains in Guandong. The mountain and river sacrifice pattern established by Qin was the first complete mountain sacrifice system in the history of the unified empire of China. In the Han dynasty, Emperor Wu of Han, guided by Confucianism, officially established the national system of offering sacrifices to the Five Sacred Mountains. In the Han dynasty, Emperor Wu of Han, guided by Confucianism, officially established the national system of offering sacrifices to the Five Sacred Mountains. As stated in the Book of Rites 《禮記》, “The emperor worships the famous mountains and rivers of the world: the Five Sacred Mountains regard the three dukes, and the Four Sacrifices regard the feudal lords. The lords sacrificed to the great mountains in their respective territories”, “天子祭天下名山大川:五嶽視三公,四瀆視諸侯。諸侯祭名山大川之在其地者”. Furthermore, the emperor established the sacrificial methods of offering sacrifices such as Fengshan 封禪, paying respects to Yue temples 親謁嶽廟, offering sacrifices in the suburbs 郊祀, offering sacrifices at the site 望祀, and sending envoys 遣使祭祀, as well as the corresponding clear sacrificial places and rituals. This system has lasted for thousands of years, making Hua Mountain, Tai Mountain, Heng Mountain, Song Mountain, and Heng Mountain among the Nine Zhenshan walk out of the ritual book and officially enter the national sacrifice, with Tai Moutain as the most respected. In the following era, the Five Sacred Mountains 五嶽 gradually took shape and took the lead in entering the national sacrifice ceremony as an independent identity, becoming a separate category of famous mountain series highly respected by the country. During the separation of Yueshan 嶽山 and Zhenshan, the relationship between Yueshan and Zhenshan underwent a sharp change. Yueshan began to surpass Zhenshan in etiquette and concepts, creating a situation where the Five Sacred Mountains were revered alone.

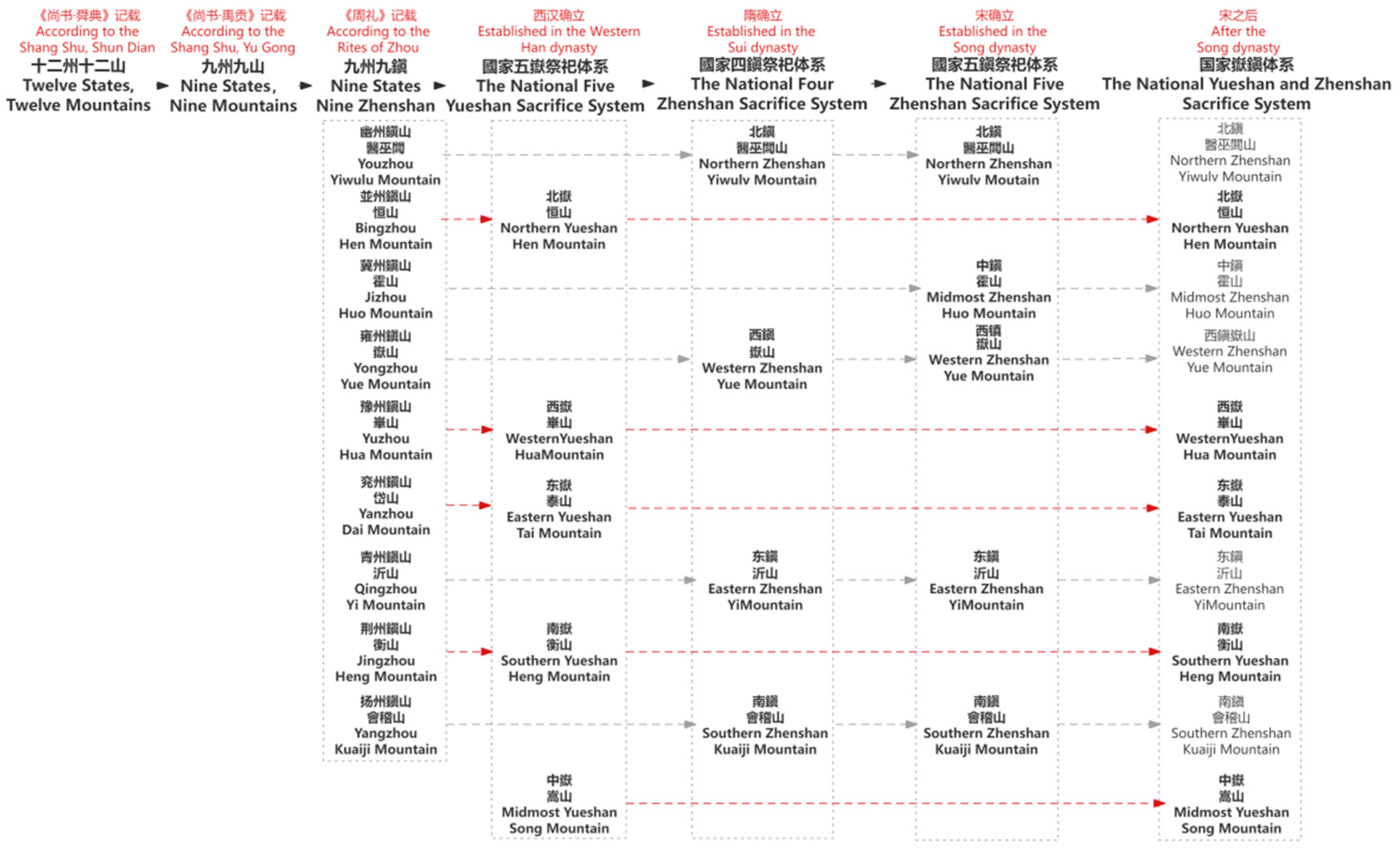

In the later period of the Northern and Southern dynasties, with the strengthening trend of national unity, the Zhenshan sacrificial ceremony also began to develop, and the main driving force for this new development was the improvement in the national mountain and river sacrificial system. The “Yizhen” 沂鎮, “Kuaiji zhen” 會稽鎮, and “Yiwulv zhen” 醫巫閭鎮 sacrificial ceremonies appeared in the Northern Qi dynasty and Northern Zhou dynasty. This trend of development continued in the Sui dynasty, which promoted the pioneering changes of Zhenshan on the basis of previous dynasties, formed the four major Zhenshan theories of the Sui dynasty, and created a complete national mountain sacrificial system. According to the “Annals of Rites” in the Book of Sui《隋書-禮儀志》, in the 14th year of Kaihuang (開皇十四年 594 AD), “an edict was issued to Yi Mountain as Eastern Zhen, Kuaiji Mountain as Southern Zhen, Yiwulv Mountain as Northern Zhen, and Huoshan as Jizhou Zhen”, “ 詔東鎮沂山,南鎮會稽山,北鎮醫無閭山,冀州鎮霍山,並就山立祠 ”. In addition to the Five Sacred Mountains system, the other four Zhenshan of the Nine Zhenshan of the Rites of Zhou were reincorporated, and the Four Zhenshan system was established. Zhenshan began to rise to the level of a national ritual system, and the injection of related sacrificial rituals such as temple construction and ritual gave Zhenshan a whole new appearance. During the Tianbao天寶 period of the Tang dynasty, the gods of the mountains and rivers were enfeoffed, and Huoshan was also included, achieving a position equal to the four major Zhenshan and developing the Zhenshan pattern. Until the Song dynasty, Huoshan was officially included in the national ritual system, and the Zhenshan sacrificial system was referred to as the Five Zhenshan. For example, the “Five Zhen” were recorded in the Zhenghe Xinyi《政和新儀》, and the completeness and institutionalization of the Zhenshan sacrificial rituals directly constructed the spiritual core of the five major Zhenshan patterns, eventually forming a complete system of national Zhenshan sacrificial rituals (Zhang 2012). During the Tang dynasty, the sacrificial level of the Five Zhen was also determined. In the second year of Yonghui (永徽二年 651 A), “Yue Zhen Hai Du” 嶽鎮海瀆 was clearly designated as the midsacrifice level in the Yonghui Decree, and this position remained unchanged throughout history (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Historical Evolution of Yueshan and Zhenshan.

In addition, from the beginning of the Han dynasty when “the five mountains regarded the three dukes” 五嶽視三公, the five mountains began to have a humanized image of the gods. Among them Mount Taishan was the Mount Taishan Prefecture Duke 泰山府君, the north was the north Yueshan Prefecture Duke 北嶽府君, and the south, north, and middle Yueshan were all dukes. Since then, the deity images of various Yue and Zhen have been continuously integrated and developed by folk legends and Taoist thought. It was not until the Tang dynasty that the gods of Yue and Zhen were gradually given titles since in the mid-Tang dynasty the deity image of the Zhenshan deity was officially established. After the Tang dynasty, various dynasties continued to use their own images of mountain deities and titles. In the Tang dynasty, there were only two levels of kings and dukes, while in the Song dynasty, higher emperors and kings appeared. In the Ming dynasty, various Yue and Zhen were directly referred to as gods. The image of the deity of each Yuezhen was determined after the Tang dynasty, it also signifies that the emperors before the Tang dynasty still regarded the god of the Zhenshan as a deity above themselves. However, with the development of history, the gods of Zhenshan accepted the titles of the earthly emperors and began to be reduced to “officials in feudal court”, so that religious worship was unified under the state power, and the “enlist enemy by offering amnesty” of the gods of the mountains was completed, which embodied the supernatural power to serve the earthly purpose and functioned as an extension of the earthly power system (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of titles for Yueshan and Zhenshan in previous dynasties.

3.3. Evolution of Zhenshan Locality—Manifestation of Confucian Education in Local Space

While the national Zhenshan sacrificial system was becoming established, Zhenshan underwent changes in imagery in the process of humanistic education guided by Confucianism, reinforcing the differentiation between Yueshan and Zhenshan. With the ritualization, folklorization, and secularization of feng shui 風水, local Zhenshan gradually formed, and the number of Zhenshan gradually increased, affecting the development of local urban and rural beliefs and spatial construction. Ultimately, a system of national Zhenshan and local Zhenshan coexisting was established, forming a multi-scale and multi-level system of the country, region, and city in space.

The connotation of Zhenshan continued to enrich and develop. With the establishment of the Five Sacred Rites system in the Han dynasty, Yueshan was differentiated into a more important Zhenshan in terms of national etiquette and people’s national concept. It replaced the Nine Zhenshan as the political propaganda significance for national unity. In the process of the differentiation of Yueshan and Zhenshan, the connotation of Zhenshan gradually shifted from Confucian political propaganda to Confucian political education. By the time of the Eastern Han dynasty, the ruling structure had gradually been established, and the emperor’s control over local administrative means was further institutionalized. As a result, the purpose of Zhenshan rituals began to return to the hope that the mountains would be a blessing to the people and country. The purpose of the Zhenshan rituals began to return to praying for the blessing of the mountains and rivers for the people and the well-being of the country. Therefore, Zheng Xuan 鄭玄 of the Eastern Han dynasty annotated the Rites of Zhou 周禮 (Zheng 2010) and wrote about “Using famous mountains to showcase and stabilize he land morality”, “鎮,名山安地德者也”. Whether it is the practical significance of agricultural production, which promotes the prosperity of the land, or the political and educational significance of “land morality” 地德, the connotation of the Zhenshan is closely related to the people. The strong propaganda significance of Zhenshan for political power was replaced by Yueshan. And with the gradual extension of Tang dynasty rituals to prefectures and counties, civil society began to actively accept and absorb the national mountain deities under the influence of the national mountain worship and gradually localized them. After the Tang dynasty, Zhenshan gradually became a psychological symbol to safeguard the lives of the people in the region, embodying their desire for a peaceful, prosperous, and beautiful life. The Yuan Chengzong Imperial Edict Stele 元成宗聖旨碑 erected in the second year of the Yuan dynasty’s Dade era 元大德二年 in the Eastern Zhen Temple provides a clear interpretation of Zhenshan: “Since three generations ago, Zhenshan has been present in all nine provinces, so the people’s livelihood is peaceful”, “三代以降,九州皆有鎮山,所以阜民生安地德也”.

Although the status of the sacrificial ritual system in Zhenshan was lower than that of Yueshan, Zhenshan still had the representativeness of royal power and the symbolic nature of ethical and hierarchical constraints; moreover, it had a metaphorical meaning of education in space. The formation of local Zhenshan 地方鎮山 and the cognition of their benefits to people’s livelihoods largely stem from the combination of the Tang and Song dynasties’ ritualization, folklorization, and secularization of feng shui with the concept of national Zhenshan sacrifice. In the construction of ancient cities, the observation of mountains was the primary principle of using feng shui theory to build cities. In the theory of feng shui, “dragon” 龍 refers to a winding mountain range, usually a mountain where qi 氣 flows through it. In the end, it forms the backing mountain 靠山, main mountain 主山, and parent mountain 父母山 of the feng shui land, and in some places, it is also called “Zhenshan” (Chen and Liu 1995). The combination of the Feng Shui dragon and Zhenshan concept is precisely because people expect to have a mountain within their living area that, like a national Zhenshan, can guard the stability of the city and the surrounding area, and ensure favorable weather conditions and seasonal resources. In feng shui, the main mountain is often tall and majestic, with a dominant position and aura. The psychological pattern reflected by feng shui overlaps with people’s expectations of the main mountain, thus forming a close combination of the two. This reflects the ideological consciousness of the vitality of mountains and waters and the compatibility with the political ethics, etiquette, and moral cultivation represented by Zhenshan. As a result, the humanization of natural mountains and waters is achieved in feng shui theory, and an effective set of norms and guidelines is established in urban landscape construction (Wu 2016).

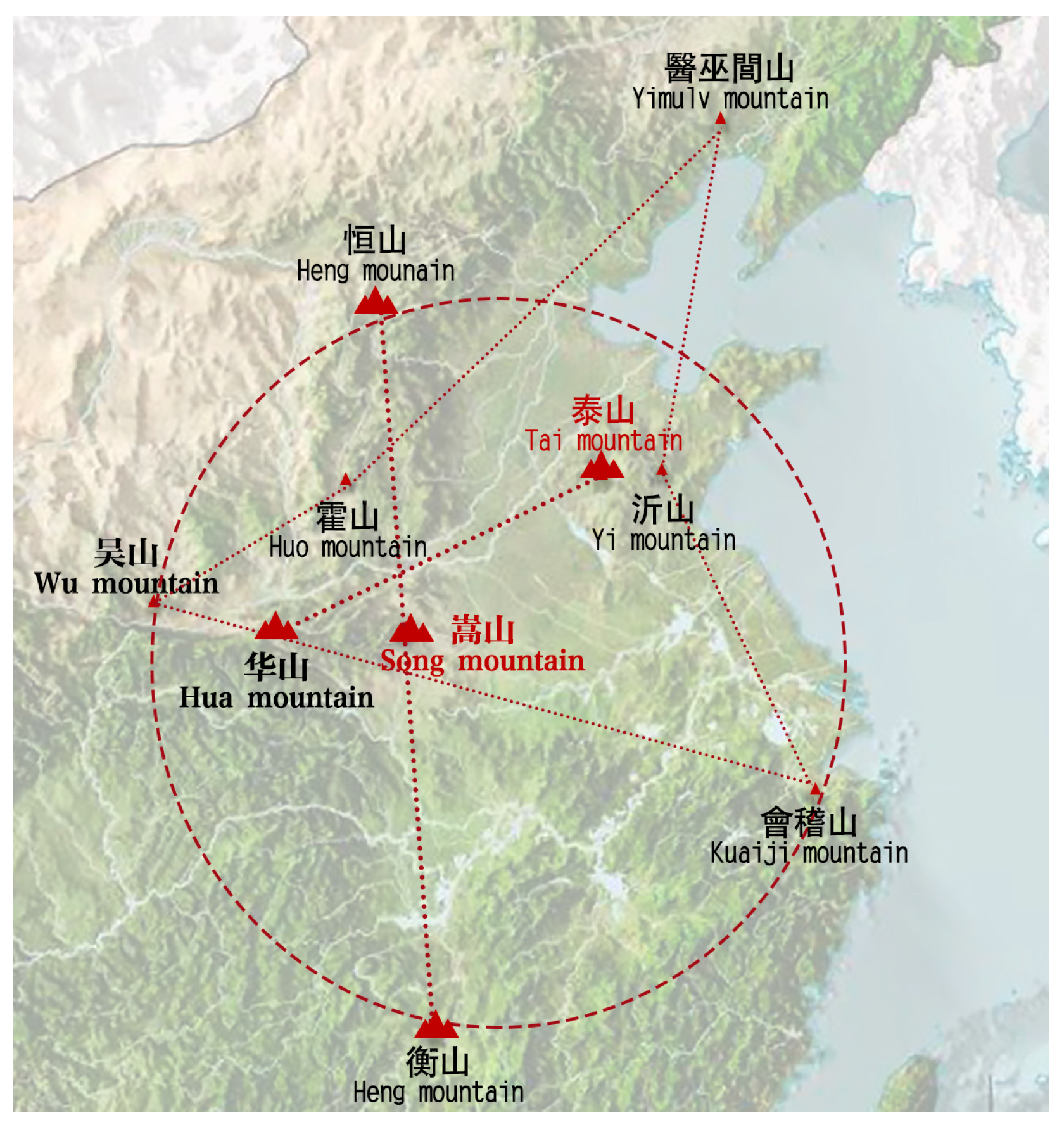

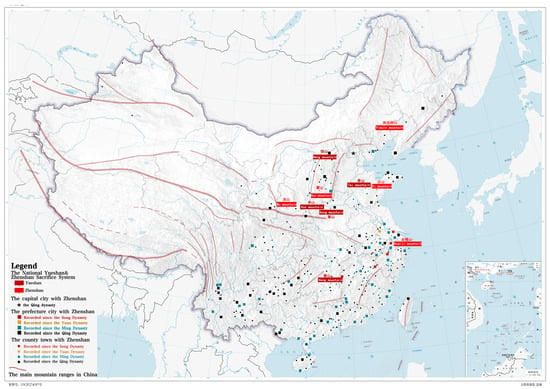

In the process of the localization of Zhenshan, regional Zhenshan and urban Zhenshan were gradually generated, and the national ritual system of Zhenshan and local Zhenshan were constructed in parallel, building a multi-level and multi-scale geospatial system comprising the national Zhenshan 國家鎮山, regional Zhenshan 區域鎮山, and urban Zhenshan 城市鎮山 at three levels. National Zhenshan refers to the ten Zhenshan included in the sacrificial system (Figure 2). In addition, Song Mountain 嵩山 is the middle mountain in the country, so it is often called the national Zhenshan by later generations, and together with Tai Mountain, it is called “Songdai” 嵩岱, which is often regarded as the national Zhenshan and the representative of the orthodox regime in the Central Plains of china.

Figure 2.

The geographical pattern of national Zhenshan.

Regional Zhenshan has two types. Firstly, the Zhenshan of each state is the regional Zhenshan that stabilizes the defense of Dehua within the nine states of the Rites of Zhou. Secondly, in the bottom-up identification of regional Zhenshan, various regions have spontaneously identified regional Zhenshan in certain areas based on dimensions such as geographical perception of local mountain ranges, observation of feng shui, cultural value, and status of mountains. Examples of regional Zhenshan include Tianmu Mountain 天目山 being the regional Zhenshan in Zhejiang Province, and Mengshan being the regional Zhenshan in Qi -Lu region 齊魯地區. At the same time, there has also been a phenomenon of multiple cities jointly designating the same mountain as a regional Zhenshan, such as the Qilian Mountains being the regional Zhenshan of four cities: Xining 西寧, Liangzhou 涼州, Ganzhou 甘州, and Suzhou 肅州.

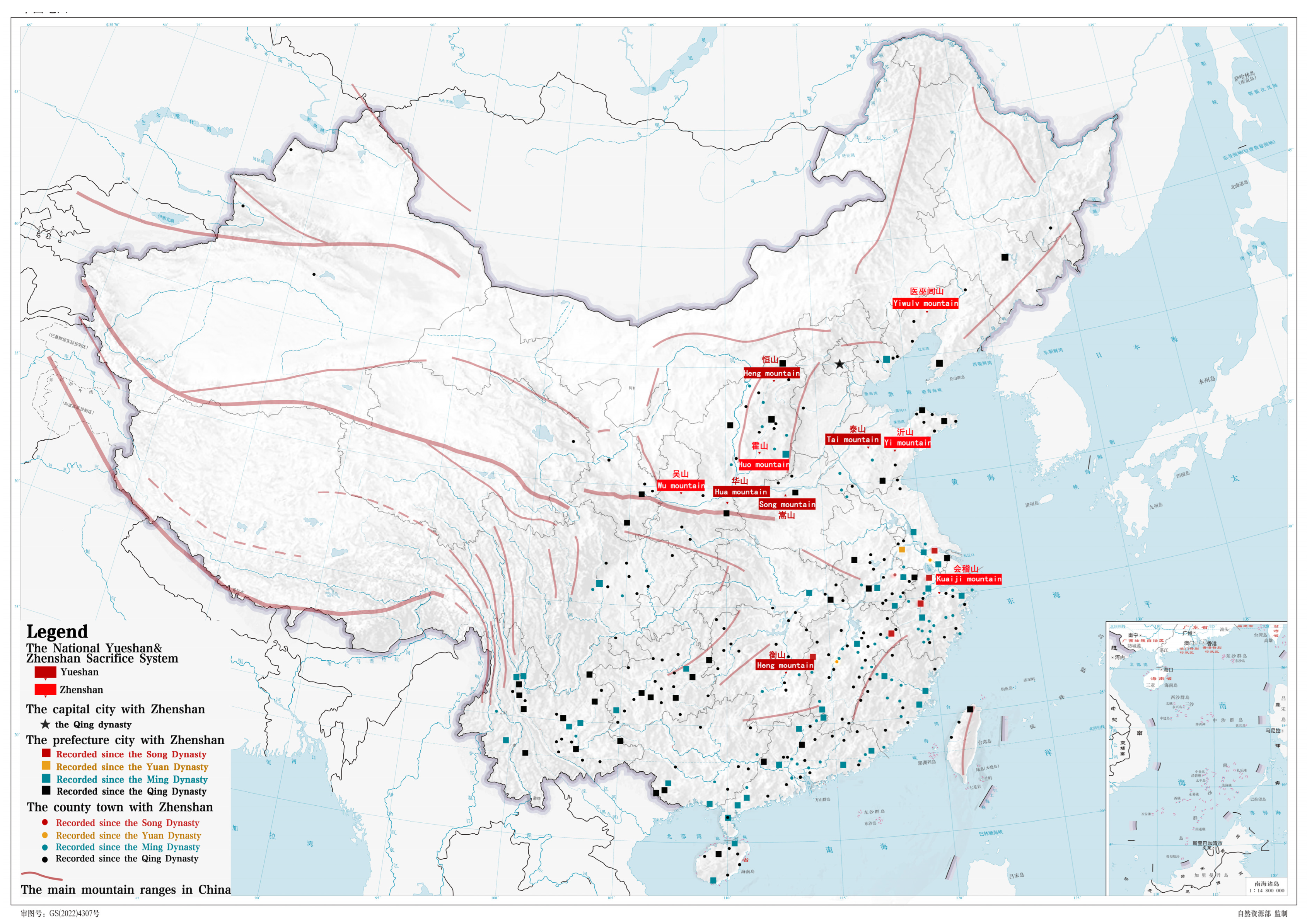

Urban Zhenshan are the most direct manifestation of the formation of local Zhenshan—they are the mountains that guard one side within the scope of urban space. According to existing local chronicles, a total of 299 cities from the Song dynasty to the Qing dynasty had their own urban Zhenshan. After the Song dynasty, Zhenshan in local cities became a common phenomenon throughout the country, becoming the main spatial element for building local collective memory and local identity. During the Song and Yuan dynasties, records of urban Zhenshan began to appear in the Jiangnan region. In the Ming dynasty, the concept of urban Zhenshan broke through the Jiangnan region and began to appear throughout the country. On this basis, the Qing dynasty continued to develop, not only expanding the breadth of the region, but also beginning to have records of urban Zhenshan in the capital city, forming a three-level administrative system of “capital city 都城–prefectural city 州府城–county town 縣城”. (Figure 3). Under different levels and scales, Zhenshan have political status differences. Local urban Zhenshan are mostly located in the tributaries of the national territory mountain range, while national Zhenshan and regional Zhenshan are mostly located on the main trunk of the national territory mountain range. Tracing upward, they ultimately belong to Kunlun Mountain, overlapping the ancient Chinese understanding of mountain ranges and their fractal structure.

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution map of urban Zhenshan in China.

4. Types and Characteristics of Worship Spaces of Zhenshan

The Zhenshan Worship Space is a typical Confucian outgrowth. It integrates Chinese natural worship into the political system and urban life, and its worship space is written in various levels of national territory. The worship of Zhenshan can be divided into the worship of its “deities” and the worship of its “forms”. The worship of its “deities” refers to the worship of the corresponding mountain deities by the Zhenshan in the national sacrificial system, thus constructing a worship space centered on temple worship. The worship of its “form” refers to the close integration of local Zhenshan with the symbols of “stability” and “guarding” due to its morphological characteristics, becoming a symbol of Confucian education and thus forming a metaphorical and restrictive worship space.

4.1. The Worship Space of Temple Sacrificial Type

Worship space based on deity worship and sacrificial liturgy is the universal form of worship space in the world’s religious cultures. The mountain deities are the main objects of worship in Chinese Zhenshan sacrifice. And with the fixation and institutionalization of worship ceremonies, the corresponding worship space also becomes more rational, and temples are the basic element and main support of sacrificial worship space.

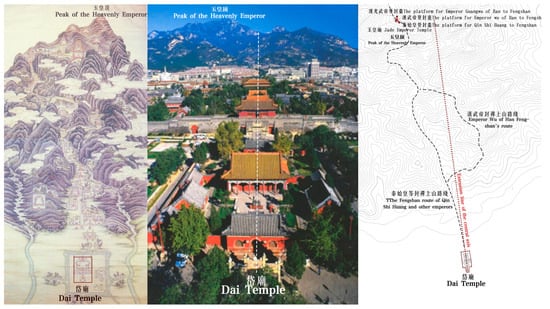

The worship space of Zhenshan under the national Zhenshan sacrificial system is based on mountain sacrificial rituals. It took the mountain as a place of worship, with religious buildings such as temples and altars as the main elements, and combined it with the mountain environment to construct a sacred temple sacrificial type of worship space. The establishment of temples is a symbol of national or folk recognition of deities. As a fixed place of worship, temples provide necessary material support for the further standardization of deity worship rituals. There are certain differences in the organization and spatial patterns of worship spaces between Yueshan and Zhenshan. According to their temple type, they can be divided into Yue temple 嶽廟 worship spaces and Zhen temple 鎮廟 worship spaces. The spatial patterns between them and the mountains can be summarized as two types: worshiping the mountain in a distant place 望祀山嶽 and building a temple on the mountain 依山立祠.

The establishment of the Yue temple concept occurred earlier than that of the Zhen temple, of which Mount Tai, which has the highest status among the five mountains, is the earliest mountain to be established as a Yue temple. Emperor Qin Shi Huang established a fixed temple as a place of worship, changing the nonfixed method of the sacrificial altar in the pre-Qin era. The practice of establishing temples on the five mountains to worship the mountain deities was followed by later generations (Yang 2011). The official record and fixed location of the Dai Temple 岱廟 in Mount Taishan originated from the Han dynasty. In addition, the Western Yue Temple in Hua Mountain was first built during the Western Han dynasty; the Medium Yue Temple in Song Mountain was first built before the Han dynasty, and was relocated to its current location during the Northern Wei dynasty; the Northern Yue Temple of Mount Hengshan was first built during the Northern Wei dynasty; and the Southern Yue Temple in Heng Mountain can be traced back to the Jin dynasty and was first built during the Sui dynasty. The ritual hierarchy and architectural regulations of the Five Yue Temples are very high, and the temples are also grand and spectacular in base and scale.

The Zhen Temple was first established in the Sui dynasty. According to the History of Sui 《隋史》, in the leap month of the 14th year of Emperor Wen’s reign, 開皇十四年 594 A, the emperor ordered the construction of Zhen temples on each Zhenshan. The establishment of Zhen temples in the Sui dynasty greatly enhanced the status of Zhenshan in national sacrifice. The Five Zhen Temples were all built during the Tang and Song dynasties: the Eastern Zhen Temple of Yi Mountain 沂山, the Western Zhen Temple of Wu Mountain 吳山, and the Southern Zhen Temple of Kuaiji Mountain 會稽山 were all built during the Sui dynasty; the Medium Zhen Temple in Huo Mountain 霍山 and the Northern Zhen Temple in Yiwulv Mountain 醫巫閭山 were first built in the Tang dynasty.

Although the emergence of Zhenshan sacrifice occurred later than that of Yue Shan, the development of Zhenshan and Yueshan in terms of sacrificial procedures and the shape of temple buildings has a certain synchronous relationship. When the concept of the Zhen temple appeared, the architectural form of the Yue temple was still immature, so the form of Zhen temples was not a simple imitation of Yue temples. Although the scale of a Zhen temple is smaller than that of a Yue temple, their construction is similar due to the universal ritual of “riding the public opinion to enter the temple gate, descending the public opinion, washing hands, descending incense, and entering the main hall” recorded in the Kaiyuan Rites of the Tang Dynasty《大唐開元禮》, New Rites of Zhenghe Five Rites《政和五禮新儀》, and Ming Huidian《明會典》.

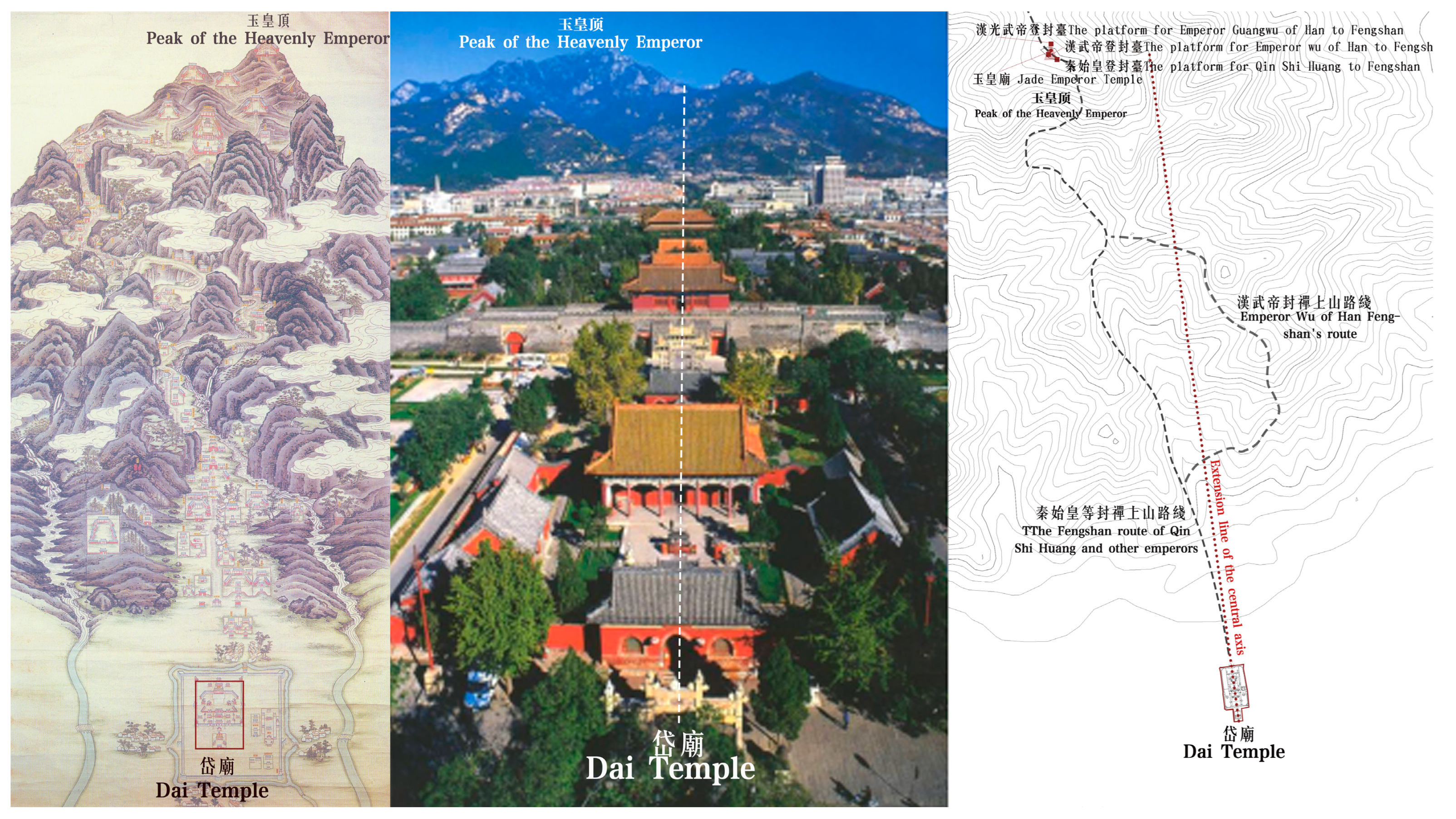

Unlike Western worship spaces dominated by gods and spirits, China’s Yue and Zhen temples are not only spaces for the worship of gods and spirits but also spaces to worship the form and trend of the mountain itself. The construction of a Zhen temple combines geographic and humanistic information to observe the mountain ranges, forming such cultural phenomena as the Wuyue Zhenxing map 五嶽真形圖 under the guidance of Taoist aesthetics. In terms of spatial order between temples and mountains, there are significant differences between Yue and Zhen temples. The setting of the Five Yue Temples and their relationship with the various mountains mainly depend on the effect of “observing and worshipping from a distance” 望祀 (Yang 2011). Ancient people worshipped the gods of the five mountains at the Yue temples, and the main peaks of the mountains became the focus of their worship. Except for the Northern Yue Temple built on the main peak, each temple is located at a certain distance from the mountain, highlighting the towering and sacred nature of the mountain with an appropriate height-to-distance ratio, forming a worship space pattern of looking at the mountain from afar and offering sacrifices. Moreover, the main peak of the mountain is often the endpoint of the central axis of each temple, forming a dignified spatial order of “mountain to temple” (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Dai Temple and Mount Taishan’s worship space for “looking at sacrificial mountains from afar” (望祀山嶽).

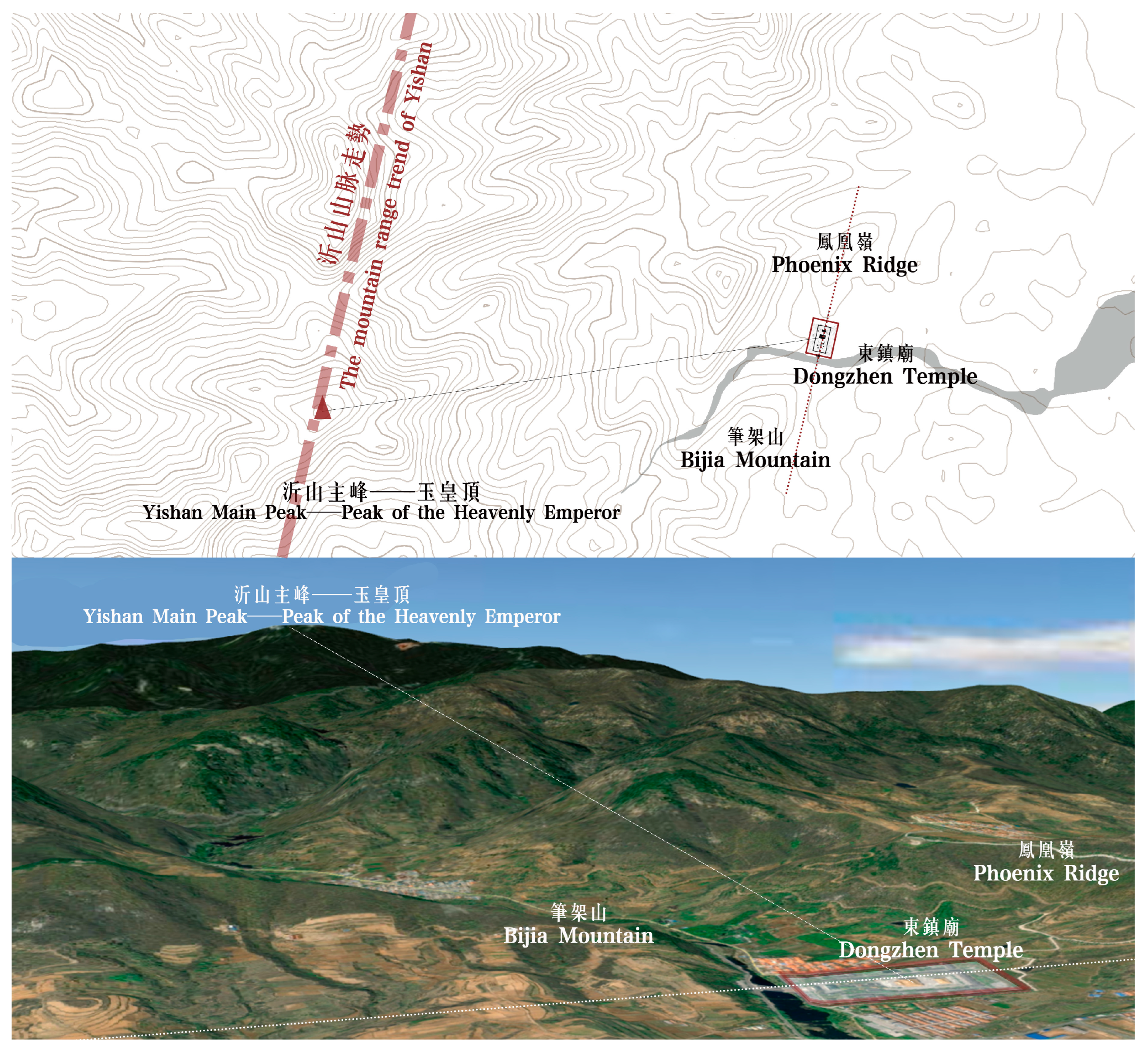

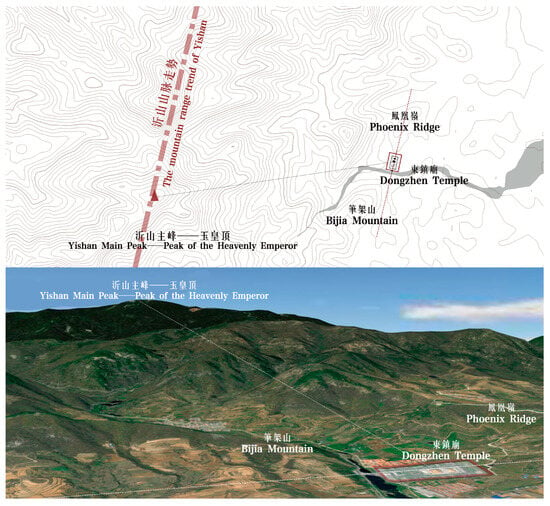

The Zhen temples and their respective mountains form a worship space pattern of “build a temple on the mountain”. The Zhen temples are mostly built at the foot or top of each mountain and are chosen to be built in areas that are sandwiched by the remaining veins of the mountain and have a sense of divinity, creating a mysterious and sacred environmental atmosphere. (Figure 5) Based on the difference in ceremonial status, there is no clear axial correspondence between the Zhen temple and the main peak of the Zhenshan Mountain range. The orientation of some Zhen temples is parallel to the overall trend of the mountain. In the construction of the spatial angle relationship between the building and the main peak, a continuous and barrier-like landscape effect is formed. In addition, compared with Yue temples, the worship space of Zhen temples pays more attention to the connection with water elements (Shen et al. 2015). Except for the Northern Zhen Temple, the other four Zhen temples use the river parallel to the mountain path as the guide for mountain worship, and the front of the temple is reached by going upstream against the current. The Eastern Zhen Temple, Western Zhen Temple, and Medium Zhen Temple are all facing water, while the Southern Zhen Temple is facing the mountain, creating a more blended “mountain to temple” worship space atmosphere (Table 2).

Figure 5.

Eastern Zhen Temple and Yi Mountain’s worship space for “standing temples along the mountains” (依山立祠).

Table 2.

Sorting out the spatial pattern of worship in Yue temples and Zhen temples.

4.2. The Worship Space of Metaphorical Constraint Type

In the process of generating the Zhenshan system, the metaphorical constraint type of worship space, based on nature worship and Confucian indoctrination, shaped political sanctity, status orthodoxy, and imagery symbols such as hierarchy, geomancy, stability, and morality to the mountain. Based on these imagery symbols, the corresponding aesthetics were extended to identify Zhenshan. And through the study of the Zhenshan system, it can be found that Zhenshan has a close relationship with the city site selection and the construction of urban spatial order, and the ancients paid attention to strengthening the association between Zhenshan and pavilions and other scenic elements. Thus, Zhenshan forms the interpretation of space for the legitimacy of the regime and forms a metaphorical space with the meaning of order, ethics, and hierarchical constraints for the people.

At the scale of national territory, the legitimacy of political power was demonstrated through the “seeking a central position” model of selecting the location of the capital city among the Nine Zhenshan, constituting a metaphorically constrained cultic spatial system in which the capital city dynamically seeks a central location among multiple Zhenshan at the geospatial scale of the national territory. According to L ü Shi Chun Qiu “Shen Shi”,《呂氏春秋·慎勢》, the ancient king chose the center of the world to establish his country, “古之王者,擇天下之中而立國”. This idea stems from the primitive worship of the center as a place for gods, the culture of seeking doctrine of the mean, and the aesthetics of mediocrity and harmony, as well as a series of concepts. The Yue Zhen Hai Du 嶽鎮海瀆 system, which gradually matured on the national territory scale after the Han dynasty, constructed spatial criteria that centered the national capital around the relative central position of spatial layout. With the migration of the national capital, the Yue Zhen Hai Du system on the national territory scale was also undergoing changes (Mao and Cheng 2020). Among them, Zhenshan is a relatively stable system in the Yue Zhen Hai Du system. The national capital takes the geographical center opposite to the national Zhenshan to represent the center of the territory, laying the foundation for the location selection method of taking the national Zhenshan as the capital and forming a spatial order of “being in the center” of the national geography. At the same time, the spatial metaphor of strengthening the legitimacy of political power is achieved by elevating the political status close to the capital city of Zhenshan. During the Tang dynasty and Northern Song dynasty, Song Mountain 嵩山 was revered as the highest of the Five Sacred Mountains due to its proximity to the eastern capitals of Luoyang and Bianjing. During the Southern Song dynasty, due to the relocation of the capital to the south, emphasis was placed on Heng Mountain. After the Ming dynasty, Beijing became the political center, and Northern Zhenshan Yiwulv Mountain held a higher status than other Zhenshan. This phenomenon reflects the dependence of the geographic political center on Zhenshan. Seeking the center in Zhenshan is a political system product of the “rule of law” society constructed by the coercive force centered on the will of the monarch, forming a geographical metaphor for the complete control of local areas by centralized and authoritarian monarchs, and consolidating the unified political order of the country (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Seeking a central position for the capital in the Zhenshan.

The urban Zhenshan is identified based on Confucian education, the superposition of the aesthetic of mountains and rivers, and is a worship of “form” based on the Confucian connotation and imagery of Zhenshan. By integrating Zhenshan with the construction of urban site selection and urban axis, and strengthening it through scenic elements such as pavilions, it becomes an important spatial coordinate for the organization of urban landscape spatial order. At the same time, urban Zhenshan serves as cultural sustenance for urban stability, prosperity, and governance, integrating local space and human life to form constraints on daily etiquette and becoming the spiritual coordinates of the city, thus forming a metaphorical constraint type of worship space.

In the identification of Zhenshan, the observation of “momentum” 勢, consideration of “form” 形, and selection of “direction” 向 are the three most basic requirements. Based on the theory of feng shui, through systematic observation of the mountain terrain and dragon veins, people generally choose peaks in the strong and connected mountain ranges as Zhenshan. Subsequently, based on visual and spatial perception, tall and well-shaped mountains with lush trees are chosen, and mountains resembling barriers, pen holders, and animals are favored to stimulate the spirituality of the city and mountains. In the selection of directions, based on the characteristics of China’s geographical climate, the best directions for Zhenshan are north, west, and northwest. The mountains in these three directions are used as supports and barriers. If there are no mountains in the northwest and north of the Zhenshan, Zhenshan will be selected from the corresponding direction of the city to fill the gap in psychological space.

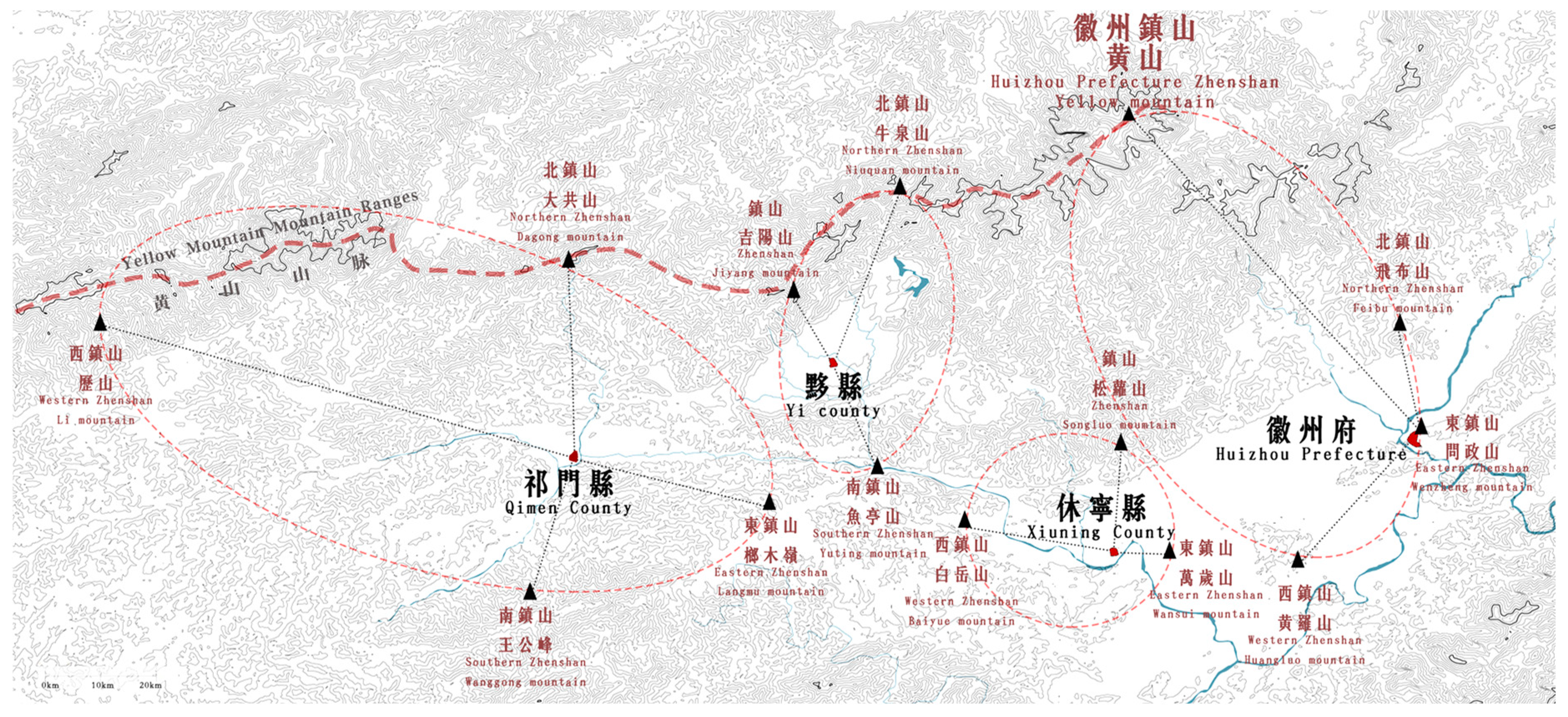

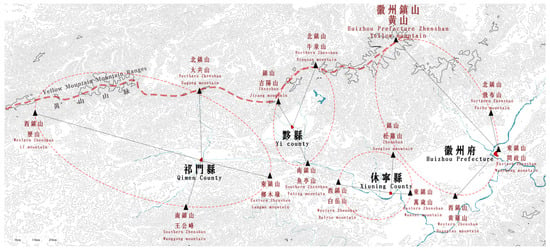

In the construction of Zhenshan and urban metaphorical constrained worship space, urban site selection and urban axis shaping are two main approaches based on the Zhenshan system. In terms of urban site selection, some cities imitate the national five Yueshan and four Zhenshan, selecting one Zhenshan from each of the city’s multiple directions, forming a phenomenon of multiple Zhenshan. The city site selection is surrounded by the Zhenshan, strengthening the political metaphor of “seeking correction in the middle” and “connecting the god in the middle”. For example, Huizhou prefecture 徽州府 and its counties are all attached to the Huang Mountains 黃山, and most of them are in a multi-Zhenshan pattern. In Huizhou prefecture, Xiuning County 休寧縣, Yi County 黟縣, and Qimen County 祁門縣, each city is located in the relative center of the multi-Zhenshan, forming a spatial pattern of “city–mountain” worship built by the multi-Zhenshan (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The spatial model of the “seeking a central position” model in the multi-Zhenshan of Huizhou prefecture.

The shaping of the urban axis imitated the model of observing and worshipping the axis of the main peak and temple in Zhenshan. By connecting urban administrative, cultural, and educational buildings with the axis, the line of sight of Zhenshan, a specific pattern is formed in space to internalize the external spatial order into the internal moral order and self-restraint, thereby making the government’s governance and education of people more sustainable and effective. Among them, Zhenshan are located in the northern part of the city, which is the most common “city–mountain” pattern. The northern Zhenshan are mostly the northern barriers and backers of the city, and the city’s political and administrative center relies on the Zhenshan, symbolizing the rule of etiquette. The northern Zhenshan form the starting point of the axis connecting mountains and cities, and form a connection in the spatial sequence of ritual governance with urban elements such as government offices, drum towers 鼓樓, Qiao towers 譙樓, and main roads. Therefore, cities with no mountains to rely on in the north often stack artificial Zhenshan in the inner city or the northern part of the sub-city 子城, such as the Wansui Mountain 萬歲山 in the northern part of the Ming dynasty Beijing Imperial City and the Wudan Mountain 武擔山 in Chengdu as Zhenshan. Zhenshan, located in the southern part of the city, also play a certain role in the formation of the urban axis structure. In the Ming dynasty, Nanjing city used Niushou Mountain 牛首山 as its “Heavenly Gate” 天闕, integrating the southern end of the city axis into nature. In Lu’an County 六安縣, since there are no mountains in the northern part of Lu’an and thus it can only rely on the mountains in the southern part of the city as a marking position for the spatial order of the city, Fan Shan 番山, as the landscape facing the political and administrative center of the city, guides the composition of the city axis, forming a composite of the functions and connotations of the Zhenshan and anshan 案山. In Xihuangshan 西晃山, Mayang County, Hunan Province, “county schools face it, and it is called zhenshan”, 縣學皆面之,為邑鎮山. In Dongguan County, Guangdong Province, Wenbi Peak文筆峰 is called Zhenshan, located in the southern part of the city, ”Faced with county school” 邑學面之. These Zhenshan, located in the southern part of the city, serve as the backdrop for county schools, playing a driving role in shaping the urban cultural axis.

In reinforcement of urban metaphorical constraint worship space, the strengthening of the pattern of pavilions and towers is an important means of shaping the psychological field in feng shui theory to achieve spatial metaphor. At the same time, pavilions and other scenic elements of Zhenshan also provide local residents with scenic spots for climbing and sightseeing, embodying the spirit of urban mountains and forests, to enhance their love for mountains and their identification with the place. For example, the halls and pavilions of Wolong Mountain 臥龍山 in Shaoxing 紹興 are built on the basis of Zhenshan; on the Wulong Mountain 烏龍山 in Zhenshan, Yanzhou 嚴州, there are pavilions such as Yuquan Pavilion 玉泉亭, Liushang Pavilion 流觴亭, Xunyou Pavilion 尋幽亭, Jingxiu Pavilion 競秀亭, and Gaofeng Pavilion 高風亭. Furthermore, like the construction of pavilions in Jinshan金山, Zhenshan of Chaozhou 潮州, as recorded in the Records of Jinshan Pavilions 《金亭山記》, ”Xumi is the zhenshan of the world. Dai, Hua, Heng, and Heng are the zhenshan of China. Jinshan is the zhenshan of Chaojun. There are also pavilions and pavilions in Jinshan, where people have vitality...the three pavilions are called Ningyuan, Chengqu, and Piyun...Without pavilions, bamboo and wood, there would be no atmosphere like Jinshan, which is the atmosphere of Chaozhou”, “須彌,天下之鎮也。岱、華、衡、恒,中國之鎮也。金山,潮郡之鎮也。郡有鎮山,猶人有元氣,……即山之陽,為亭者三,曰凝遠、曰成趣、曰披雲...非亭榭竹木,無以為金山之氣象,實潮之氣象也”. Through the construction of pavilions on Jinshan, the “atmosphere of Chaozhou” and “the harvest of agriculture and the prosperity of official transportation” are strengthened (Mao 2015).

5. The Dissemination of the Zhenshan System

The worship of mountains in neighboring overseas vassal states and the enfeoffment of overseas Zhenshan during the Ming dynasty were the main reasons for the influence of Chinese mountain worship overseas and the spread of the Zhenshan system in Asia. History of Ming Dynasty, “The Book of Rites” 《明史·禮志》, records the history of Emperor Taizu sending officials to offer sacrifices to various vassal states such as Annam 安南, Goryeo 高麗, Champa 占城, Ryukyu 琉球, Zhenla 真臘, Siam 暹羅, Suoli 鎖裏, Sanfoqi 三佛齊, Juava 爪哇, Japan, and Boni 渤泥. “According to the officials, the mountains and rivers in each province face south from the center, while foreign mountains seeking a central position worshipped together on the same altar. The worship of his kingdom’s mountains and rivers was stipulated in the 13th year of the Hongwu reign”, “又從禮官言,各省山川居中南向,外國山川東西向,同壇共祀。其王國山川之祀,洪武十三年定制”. And the system of mountain and river worship was extended overseas. During Zheng He’s 鄭和 voyages to the Western Seas, he bestowed upon the various overseas vassal states the title of Zhenshan: Mount Xishan was enfeoffed as the Zhenshan of Man Ci Jia 滿刺加國, Mount Changning 長寧 was enfeoffed as the Zhenshan of Bohai 渤泥國, Mount in Kezhi 柯枝 was enfeoffed as the Zhenshan of Kezhi 柯枝, and Mount Shouan 壽安山 was enfeoffed as the Zhenshan of Japan.

The enshrinement of the overseas Zhenguo Mountain reflects the Ming dynasty’s sense of unity among the feudal lords. At the same time, Zhenshan has political and military deterrence. And some of the weaker states took the initiative to ask to be enshrined in order to obtain the protection and support of the Ming dynasty. The enshrinement of the overseas Zhenguo Mountain not only facilitated the implementation of the Ming dynasty’s tribute policy, it also promoted the stability and social and cultural development of countries in Southeast Asia and East Asia (He 1997). The awarding of calendars, crowns, costumes, rituals, and imperial examination systems to the enshrinement of the Zhenshan Kingdom, as well as the gift of books, musical instruments, and weights and measures, as well as the permission for tribute trade with China, reflect the historical tradition and foreign policy of “The selfless contribution of the king to the outside world is a manifestation of Wang’s morality”, “王者無外,王德之體”, and thus create a magnificent situation of “All nations are all guests, and the world will be peaceful”, “萬國鹹賓天下治平”, in a prosperous imperial dynasty. This embodies the Chinese civilization’s expectation for the world to be unified in harmony, with no boundaries between the inside and outside, regarded as one, and to be renowned far and wide in Suining.

At the same time, enshrining the overseas Zhenshan also had a certain impact on the vassal states. In addition to the Zhenshan enshrined by the Ming dynasty, other countries also developed their own local Zhenshan, which influenced the spatial construction of the city to a certain extent. Essentially, the local Zhenshan of other countries were similar to China’s metaphorically constrained worship space, relying on the political imagery of Zhenshan to play a role in spatial indoctrination. Among them, the country of Korea had the most profound and extensive influence. The Records of the Four Barbarians《四夷廣記》 and Korean Annals《朝鮮志》extensively record the cities and towns of Korea, such as “Songyue is the zhenshan of Kaesongfu”, “開城府是為京畿道設留守官松嶽其鎮山也”; ”Tianma mountain is the zhenshan of dingzhou”, “定州其鎮山為天馬山”; ”Tianshan county’s zhenshan is xionggu mountain”, “鐵山郡其鎮山為熊骨山”; “Sanjiao mountain is zhenshan of the capital city”, “三角山實京城之鎮山也”; and “Longgu Mountain, also known as Longhu Mountain, is the zhenshan located in Dongbali Town, Longchuan County, Ping’an Road”, “龍骨山,一名龍虎山在平安道龍川郡東八裏鎮山”. The naming method, description of the situation, and relationship with the order of the city of Zhenshan are very similar to those of the Chinese city of Zhenshan. In addition, according to Vietnam’s Revised Vietnam Illustrated Book《重訂越南圖說》, “Mount Bonan is located within the territory of the newly established Nanpan Kingdom. The mountain is very high and serves as zhenshan”. In the Annals of the Ryukyu Islands《使琉球紀》there are also records of local Zhenshan, which shows the impact of enshrining overseas mountain worship on the country’s own Zhenshan worship system.

6. Conclusions

Chinese worship space constructed on the basis of natural order incorporates the relationship between humans, gods, and nature into a unified picture of harmonious existence, of which Zhenshan is a typical representative. In the process of the generation and development of Zhenshan, the continuity of natural divinity across primitive societies was its basic premise. In the late period of tribal alliances, mountain worship was combined with politics. With the unification of national geography and the establishment of national systems, mountain worship gradually attached itself to symbols of hierarchy, territory, and national stability, culminating in the formation of the concept of Zhenshan in the Zhou dynasty. In the historical development process dominated by Confucianism as the political concept, the Zhenshan concept was finally officially integrated into the national mountain worship system and the Zhenshan worship system was established. At the same time, with the gradual stabilization of the national governance structure, the imagery of Zhenshan was strengthened toward the direction of indoctrination and was gradually integrated into local beliefs and combined with feng shui theory, landing in local spatial practice. Ultimately, corresponding to the national mountain worship system and the local “city–mountain” system, the worship space of Zhenshan forms two types, temple sacrifice type and metaphorical constraint type. Among them, the metaphorical constraint type of worship space has the uniqueness of the Chinese mountain worship space. Based on the fixed imagery of Zhenshan, it plays a role in education through site selection and urban spatial order construction. Finally, based on the political means of sending officials to worship the mountains and rivers of their vassals, Zhenshan generated overseas dissemination and had a certain influence on mountain worship practices and mountain worship space in East Asian countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M. and S.T.; methodology, H.M.; software, S.T.; validation, H.M. and S.T.; formal analysis, H.M. and S.T.; investigation, S.T.; resources, H.M.; data curation, H.M. and S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M. and S.T.; writing—review and editing, H.M. and S.T.; visualization, H.M. and S.T.; supervision, H.M.; project administration, H.M.; funding acquisition, H.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China’s general project “Study on the landscape paradigm and evolution mechanism of ‘city–mountain’ space in ancient China” (5237082015), and Chongqing Social Science Planning Foundation Project ”Research on Resource Identification and Local Construction Approach of national parks with Yangtze River culture as their theme (Chongqing Section)” (2023ZD08).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bernbaum, Edwin. 1997. The Middle East: Heights of Revelation. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 86–103. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart, Jacob. 2008. Greeks and Greek Civilization. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, p. 596. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Hong 陳宏, and Peilin Liu 劉沛林. 1995. The impact of feng shui spatial patterns on traditional urban planning in China. Urban Planning 19: 18–21+64. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Shuang 杜爽, and Feng Han 韓峰. 2019. A Study on the Origin of Foreign Holy Mountains from the Perspective of Cultural Landscape. Chinese Landscape Architecture, 122–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliade, Mircea, and Kejia Yan. 2008. The Divine Existence: A Paradigm of Comparative Religion. Translated by Beiqin Yao. Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press, p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- Feuerbach, Friedrich. 1959. The Essence of Religion. Translated by Fu Wang. Beijing: Commercial Press, p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Hongming 辜鴻銘. 2018. The Spirit of Chinese People. Beijing: Beijing Publishing House, p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- He, Pingli 何平立. 1997. A Brief Discussion on Overseas Zhenshan and Zheng He’s Voyages to the West in the Early Ming Dynasty. Journal of Shanghai University: Social Sciences Edition 4: 107–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Lancheng 胡蘭成. 2013. The Scenery of Rites and Music in China. Beijing: China Chang’an Publishing House, p. 204. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Haohui 靳浩輝. 2017. Comparison between Confucius’ “Integration of Politics and Religion” and Jesus’ “Separation of Politics and Religion”: An Analysis of “Political and Religious Views” from the Perspective of China and the West. Guangxi Social Sciences 3: 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Xiaodong 廖曉東. 2008. Political Ritual and Power Order: A Political Analysis of the “National Sacrifice” in Ancient China. Shanghai: Fudan University. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Huadong 毛華松, and Yu Cheng 程語. 2020. Identifying the Region and Rectifying the Order, and Shaping the Cities and Countryside: Study on Landscape Imagery and Historical Influence of Capital Construction System in Rites of the Zhou. Chinese Landscape Architecture 36: 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Huasong 毛華松. 2015. Research on Public Gardens in the Song Dynasty under the Evolution of Urban Civilization. Chongqing: Chongqing University. [Google Scholar]

- Naquin, Susan, and Chün-Fang Yu, eds. 1992. Pilgrims and Sacred Sites in China. Berkeley: University of California Press, vol. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Needham, Joseph. 1975. History of Science and Technology in China (Volume 1, General Introduction, Volumes 1 and 2). Beijing: Science Press, p. 910. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, James. 2009. Power of Place: The Religious Landscape of the Southern Sacred Peak (Nanyue) in Medieval China. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Yang 沈旸, Xiaodi Zhou, and Yong Liang. 2015. Zhenshan and Zhenmiao: Architecture and Landscape Presentation in Ancient Mountain and River Worship. Chinese Garden 31: 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sima, Qian 司馬遷. 2019. Records of the Grand Historian 史記. Selected Annotations by Bingxin Xie. Chengdu: Sichuan People’s Publishing House, p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Xiaochun, and Jacob Kistemaker. 1997. The Chinese Sky During the Han: Constellating Stars and Society. Leiden, New York and Koln: Brill, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Guixian 王貴祥. 2002. A Comparison of the View of Nature in Chinese and Western Cultures. Chongqing Architecture 25: 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Hui 王暉. 1999. On the Nature of Heavenly Gods and Mountain Worship in the Zhou Dynasty. Journal of Beijing Normal University: Social Sciences Edition 1: 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Liqiu 王立秋. 2022. Research on the Worship of Mountains and Rivers in the Pre Qin Period. Chongqing: Southwest University. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Shishun 王世舜. 2018. Shangshu 尚書. Translated and Annotated by Cuiye Wang. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, p. 494. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yi 王毅. 2004. History of Chinese Garden Culture. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, p. 485. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Maoguo 伍茂國. 2004. From the Origin of Religious Consciousness to See the Differences in Chinese and Western Outlook on Life. Journal of Guangdong Education Institute 04: 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Ran 吳然. 2016. Research on the Cultural Tradition and Landscape Planning of the Shanshui Cities in Sichuan Basin. Beijing: Beijing Forestry University. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Bo 楊博. 2011. Research on the Architectural System of the Five Sacred Mountains in China. Beijing: Tsinghua University. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Huaitong 張懷通. 1994. The People-Oriented Spirit and Political Function of Mountain and River Sacrifices in the Zhou Dynasty. Yin Du Xue Bao 04: 25–28+44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Mu 張目. 2012. The Structure Investigation on Sacrifice of Ancient National Chief Mountains. Zhuhai: Jinan University. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xiqian 張希茜. 2016. The National and Religious Significance of Mount Sinai in Judaism. Jinan: Shandong University. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Xuan 鄭玄. 2010. Annotations on Zhou Li 周禮注疏. Shanghai: Shanghai Chinese Classics Publishing House, p. 1745. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Hua 鄒華. 1999. Exploring the Cultural Origins of Chinese and Western Aesthetics. Seeking Truth. 26: 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Qiuming 左丘明. n.d. Zuo Zhuan. Taiyuan: Sanjin Publishing House, p. 240.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).