1. Introduction

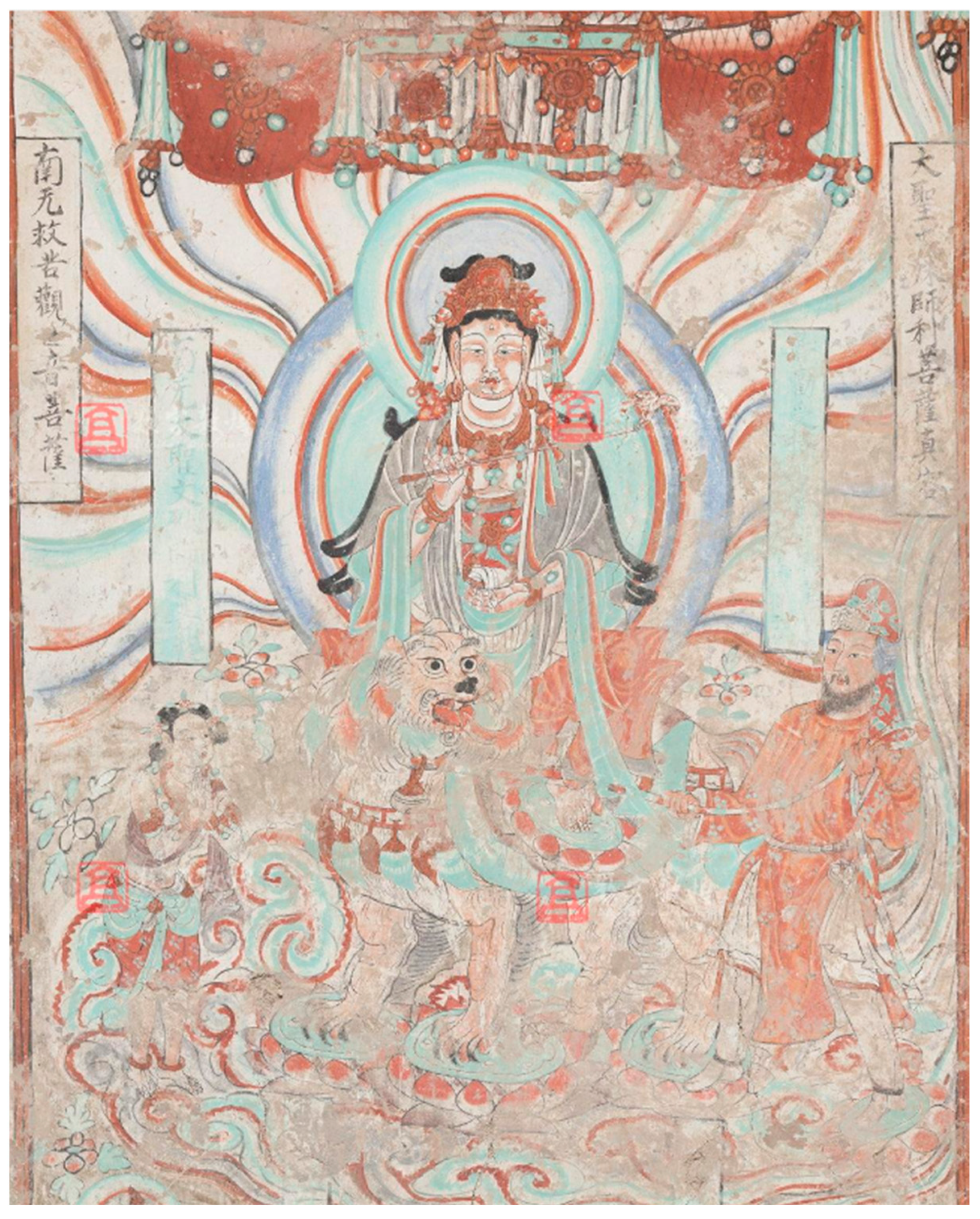

In 1975, restoration work at the north wall of the corridor in Mogao Cave 220 in Dunhuang, China, revealed an early tenth-century mural that had been hidden for centuries underneath a later layer of painting applied in the Western Xia period (1038–1227) (

Dunhuang Wenwu Yanjiusuo 1978). The most significant part of that discovery is a group of images in the central frame of the Mañjuśrī bodhisattva (a major deity in the Buddhist pantheon representing transcendental wisdom) riding on a roaring lion, attended by a boy and a Central Asian lion tamer. The trio are set on billowing clouds with five-colored rays emitting from the background. An inscription below this saintly group identifies it to be “the new-model of Great Sage Mañjuśrī bodhisattva and His Attendants (新样大圣文殊师利菩萨一躯并侍从)” (

Figure 1).

This new-model Mañjuśrī, as past scholarship has convincingly established, was based on a novel depiction of Mañjuśrī developed at Mount Wutai in the Tang period (

Rong 1987). This depiction was believed to have been made through divine intervention, as legend tells that the bodhisattva manifested his “true visage” (

zhenrong 真容) to the artisan at Mount Wutai. Thus considered more authentic than previous representations of the bodhisattva, the True Visage Mañjuśrī was a crucial part in the historical process of sacralizing Mount Wutai and establishing this Chinese site as the abode of Mañjuśrī. Understanding how the True Visage Mañjuśrī differed from earlier representations is therefore not only of art historical importance, but also crucial to fully illuminating the rise of the cult of Mount Wutai, a milestone development in the history of Chinese Buddhism.

Despite past scholarly efforts, two puzzling aspects still lurk in our understanding of the visual formula of the new-model Mañjuśrī (considered to represent the True Visage Mañjuśrī), which form the starting point of this paper. Firstly, examining all images classified as the new-model Mañjuśrī has led scholars to conclude that the primary new aspect of that model is not the depiction of the bodhisattva per se, but the ethnicity of the lion tamer attendant. It is puzzling that the true visage of a saintly figure is defined externally, by his attendant, rather than internally, within his own stylistic or iconographic configuration. Secondly, all textual sources related to the images of the True Visage Mañjuśrī are silent on the subject of attendant figures. This silence would suggest that attendant figures were not considered important constituents of the True Visage Mañjuśrī, which sows serious discord with modern scholarly understanding based on the visual materials.

1In recognizing the connection between the new-model Mañjuśrī and the True Visage Mañjuśrī invented at Mount Wutai, however, this paper questions the visual identity of the two—ultimately, there is no evidence to confirm that the former transmits the iconographic composition of the latter in full. In re-defining the group of images that more likely represent the True Visage Mañjuśrī invented at Mount Wutai and re-evaluating the iconographies of this important image type, this paper argues that the True Visage Mañjuśrī debuted at Mount Wutai has specific iconographic features, in his own representation, that distinguish this image type from earlier representations of the deity. Uncovering these heretofore neglected iconographic specificities brings new insights to the multifaceted development of the cult of Mount Wutai, and this paper attempts to interpret the role and significance of these features in the formulation of the True Visage Mañjuśrī at Mount Wutai. Finally, this paper discusses if and how the absence of these iconographic specificities affected the reception of the new-model Mañjuśrī in Dunhuang and aspires to engender renewed thinking about the notion of auspicious images and their replication.

2. The Gap between Modern Scholarly Understanding and the Transmitted Texts

Before setting out to re-evaluate the iconography of the True Visage Mañjuśrī, it is helpful to review the conventional scholarly understanding in more detail. The visual history of Mañjuśrī in China can be traced to at least the fifth century: the earliest extant depiction is located in a cave in Bilingsi Grottoes, Gansu, with an inscription for the year 420. Early images of Mañjuśrī are hardly distinguishable from those of other bodhisattvas in terms of posture, dress, hand-held attributes, or animal vehicles, and scholars depend on the accompanying inscriptions or the context of appearance for their identification. The late sixth century saw a turning point in the representations of Mañjuśrī, however, as the newly added lion became the deity’s iconographic animal vehicle (

Sun 2007, pp. 36–45). The emergence of the True Visage Mañjuśrī ought to reflect the next defining moment in the visual history of the bodhisattva, yet past attempts to pin down what exactly is new in the depiction of the bodhisattva in his True Visage image have not yielded satisfactory results.

Comparative examinations of images believed to be representing the True Visage Mañjuśrī in Dunhuang, Mount Wutai, and various other sources have led scholars to conclude that the posture, style of dress, and other details of the bodhisattva all vary image by image. The only common feature unifying these images appears to be the ethnicity of the accompanying lion tamer.

2 Instead of a South Asian man with curly hair, as in older representations of Mañjuśrī and his entourage, an aged figure with prominent Central Asian features, and wearing a specific outfit composed of a hat, a robe, and boots takes up the role of the lion tamer in the new depiction. Scholars further identify this new figure as the Khotanese King in the widely circulated legend “Bodhisattva Manifesting His Body as a Poor Lady”. According to the

Guang Qingliang Zhuan (Extended Records of Mount Clear and Cool, a comprehensive record about Mount Wutai compiled in 1060; hereafter the Extended Records) in which the legend is recorded, Mañjuśrī, in the guise of a poor lady, comes with two boys and a dog to beg for food at a feast held by Dafu Lingjiu Monastery. The monk at service gives her three people’s shares of food, but she asks for more for the dog and again for an unborn baby she claims that she is carrying. The monk becomes angry and criticizes her harshly for her insatiability. She thereupon rises straight from the ground to manifest her true form as bodhisattva Mañjuśrī and transforms the dog into a lion and the two boys into Sudhana and the Khotanese King. The saintly group then disappears into thin air, leaving behind clouds of five colors.

3While the legend justifies the Khotanese King as a useful element representing the vision of Mañjuśrī manifesting his true form on Mount Wutai, whether that element could be seen as the most crucial determinant of the authority and authenticity of the True Visage image associated with Mount Wutai is in doubt. For one thing, textual records related to the True Visage icons of the bodhisattva in Mount Wutai make no mention of the attendants. In the diary by the Japanese Buddhist pilgrim-monk Ennin (composed circa 847–858), he recorded a vivid impression of the great image of Mañjuśrī enshrined in the Great Huayan Monastery, which was the icon after which all Mañjuśrī images on Mount Wutai were modeled (今五台诸寺造文殊菩萨像皆此圣像之样):

4We opened the hall and worshipped a great image of the bodhisattva Mañjuśrī. Its appearance is solemn and majestic beyond compare. The figure riding on a lion fills the five-bay hall. The lion is supernatural. Its body is majestic, and it seems to be walking, and vapors come from its mouth. We looked at it for quite a while, and it looked just as if it were moving.

5

Despite his vivid description of the magnificent icon, Ennin wasted no ink on the attendant figures. Two possibilities can be inferred to explain this: either the icon Ennin saw had no flanking attendants, or Ennin simply did not see a need to elaborate upon the attendant figures. Based on extant Mañjuśrī statues in Foguang and Nanchan Monasteries (Figures 3–7), both accompanied by the boy Sudhana and the Khotanese King, it might be that the icon Ennin viewed also had the same attendants.

6 However, the absence of their mention in the record suggests that the attendant figures were not seen in Ennin’s eyes as critical constituents of the True Visage image.

Ennin went on to record the miraculous happenings when the True Visage icon was made:

The venerable monk [in the hall] told us that when they first made [the statue of] the Bodhisattva, they would make it and it would crack. Six times they cast it, and six times it cracked to pieces. The master was disappointed and said, “Being of the highest skill, I am known throughout the empire, and all admit my unique ability. My whole life I have cast Buddhist images, and never before have I had them crack. When making the image this time, I observed religious abstinence with my whole heart and used all the finesse of my craft, wishing to have the people of the empire behold and worship it and be specially moved to believe, but now I have made it six times, and six times it has completely cracked to pieces. Clearly it does not meet the desire of His Holiness. If this be correct, I humbly pray that His Holiness the bodhisattva Mañjuśrī show his true visage to me in person. If I gaze directly on his golden countenance, then I shall copy it.” When he had finished making this prayer, he opened his eyes and saw the bodhisattva Mañjuśrī riding on a gold-colored lion right before him. After a little while [Mañjuśrī] mounted on a cloud of five colors and flew away up into space. The master, having attained the vision of [Mañjuśrī’s] true visage, rejoiced [but also] wept bitterly, knowing then that what he had made had been incorrect. Then, changing the original appearance [of the image], he elongated or shortened, enlarged or diminished it [as necessary], so that in appearance it exactly resembled what he had seen, and the seventh time he cast the image it did not crack and everything was easy to do, and all that he desired was fulfilled.

7

The origin story of the True Visage icon similarly talked only about the bodhisattva and his lion and spared no words for any attendant figure(s). Such silence on the attendant figures of the image of the True Visage Mañjuśrī is repeatedly seen in Ennin’s description of other Mañjuśrī statues he visited on Mount Wutai as well as in the relevant passages about the True Visage icon in the

Extended Records.

8 The conspicuous neglect of attendant figures in all medieval accounts related to the images of the True Visage Mañjuśrī at Mount Wutai suggests clearly that the attendant figures were not understood as the defining component of the True Visage Mañjuśrī—only the bodhisattva and his lion were regarded as integral to the True Visage image.

Lin Wei-cheng and Choi Sun-ah have attempted inspiring explanations for this text–image discrepancy (

Lin 2013, pp. 93–94;

Choi 2012, p. 183). Their theories are essentially similar: the True Visage Mañjuśrī associated with Mount Wutai indicates a conceptual innovation—a new emanation of Mañjuśrī at Mount Wutai—rather than new stylistic or iconographic details associated with the bodhisattva’s representation. Therefore, Lin and Choi contend, respectively, that the cloud motif and the Khotanese King help to define the particular vision of Mañjuśrī’s manifestation on Mount Wutai. Their attention to the conceptual component of the True Visage image is inspiring, but there is still scope to question this. While conceptual novelty is a crucial constitutive element for auspicious images, specific iconographic or stylistic details are also essential for differentiating auspicious images from regular depictions of the same deity and for visually marking their religious distinctness. On this ground, I hesitate to accept that the cloud motif and the Khotanese King were originally conceived for such an important function as unique visual identifiers. The doubt with the cloud motif is due to its overly generic character. Its very broad range of application—to represent the manifestation or descent of various other deities such as Avalokiteśvara, Kṣitigarbha, or Vaiśravaṇa—reduces its visual specificity to the very vision of Mañjuśrī’s manifestation at Mount Wutai.

9 Indeed, the interest in using clouds to represent the descent or manifestation of divinities became especially prominent in medieval China.

10 As such, while the cloud motif may have been a supplementary device, it lacks the power to distinctly mark the novelty of the True Visage Mañjuśrī as a main visual indicator.

The Khotanese King can provide a more specific reference to the vision of Mañjuśrī at Mount Wutai, and on this ground, many scholars have identified it as the crucial indicator guaranteeing the authenticity and geographic specificity of the True Visage Mañjuśrī. My reservation with this theory is based on a chronological consideration, in addition to the above-discussed silence on attendant figures in accounts pertaining to the True Visage icon. An analysis of the development of the tale “Bodhisattva Manifesting His Body as a Poor Lady” would suggest that the Khotanese King most likely became officially incorporated into the narrative only until much later. As recorded in the Extended Records, the poor lady, who was the disguise of Mañjuśrī, was accompanied by two boys and a dog, who turned out to be the Khotanese King, boy Sudhana, and Mañjuśrī’s lion vehicle. Yet, the Extended Records was compiled in 1060, long after the creation of the True Visage image in the eighth century. Ennin’s diary, compiled in the mid-ninth century contains an earlier version of the story “Bodhisattva Manifesting His Body as a Poor Lady”. In the ninth-century version, only the lady herself was mentioned while the lion also appeared following Mañjuśrī’s revelation of his bodhisattva form. Neither the Khotanese King nor the Sudhana boy was mentioned at this time. The narrative focus on Mañjuśrī and the lion alone indeed agrees with contemporary descriptions of the True Visage image discussed above—only Mañjuśrī and his lion mattered in the first two centuries of the True Visage icon’s creation. The substantially lagged incorporation of the Khotanese King in the literary tradition therefore suggests that the figure belonged to a later phase of the tale’s development, which militates against the possibility that the Khotanese King was conceived as a visual cue evoking the conceptual component of the True Visage Mañjuśrī at the time of the image’s formulation. The last section of this paper will provide further discussion of this point.

In summary, there appears to be a major gap in modern scholarly understanding that foregrounds the Khotanese King as the single criterion defining the True Visage Mañjuśrī associated with Mount Wutai. This gap compels us to re-evaluate the modern scholarly understanding and consider the following again: is it really the case that the True Visage Mañjuśrī developed at Mount Wutai lacks any specific visual features to distinguish itself from earlier representations of this deity at the height of its cult?

3. Discovering Specific Iconographic Features of the True Visage Mañjuśrī

The group of images conventionally perceived as representing the True Visage Mañjuśrī, and serving as the objects of comparative examination in search for their shared characteristics, includes the mural in

Figure 1 and other new-model images in Dunhuang, several dozen woodblock prints unearthed from Mogao Cave 17 (

Figure 2), and extant Mañjuśrī statues enshrined in monasteries on or nearby Mount Wutai (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

11 Unfortunately, a comparative examination has not borne much fruit other than revealing the Khotanese King as a common element in the depiction.

Conditioning this approach is the presumption that all these images retain the most crucial feature of the original True Visage image invented at Mount Wutai, if there ever was such a feature. This presumption is, however, unsubstantiated. If any one of those images deviates from the original in precisely the depiction of the most crucial feature, then any attempts to identify this crucial feature by looking for commonalities in pictorial depictions are doomed to fail. One question that ought to be asked is whether such new-model Mañjuśrī images as depicted in

Figure 1 really transmit the iconographic essence of the True Visage image at Mount Wutai. Despite the literary association suggested by the appellation in its right-hand cartouche “True Visage of the Great Sage of Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī”, there is little direct evidence that the bodhisattva in

Figure 1 indeed captures all the defining details of the original True Visage image at Mount Wutai. Such ambiguity renders results from past analyses inconclusive.

To overcome this ambiguity, this paper redefines the group of images that ought to belong unambiguously to the type of the True Visage Mañjuśrī at Mount Wutai. It begins by examining the extant Mañjuśrī statues in the Wutai area. The first statue is enshrined in the Nanchan monastery. Though the monastery is located slightly outside the core area of Mount Wutai, its icon is the earliest extant image of the True Visage Mañjuśrī and is conventionally dated to around 782 based on the reconstruction date of the monastery (

Figure 3). A slightly later statue is preserved in Foguang Monastery in Mount Wutai, dated to the late eighth or the ninth century based on the style of the sculpture and the architecture (

Figure 4). To the left of the main gate of the Foguang Monastery is the Hall of Mañjuśrī, in which another set of statues made in 1137, including a Mañjuśrī statue, have also survived to the present day (

Figure 5).

12Although the three Mañjuśrī statues in the Wutai region display different stylistic traits reflecting their creation at different moments in history, they exhibit remarkable consistency in their iconographic configuration. While the statue shown in

Figure 3 has its legs crossed in the lotus position—which may have been an earlier design before the posture became codified—the two later Mañjuśrī images are seated in the royal ease position, with the right leg tucked inward on the seat and the left leg hanging. Furthermore, all statues have their right hand raised and left hand lowered and extending forward to hold a

ruyi (“as you wish”) scepter. Such consistency in posture points to a common model, corroborating Ennin’s record that all Mañjuśrī images on Mount Wutai followed the example of the great image of Mañjuśrī enshrined in the Great Huayan Monastery.

Even more noteworthy than the consistent posture is the special dress of these Mañjuśrī images in the Wutai region. Occasionally, earlier representations of Mañjuśrī were also rendered in the royal ease position or depicted as holding a

ruyi scepter; hence, the posture’s iconographic specificity with the True Visage Mañjuśrī is less definitive.

13 However, the dress of these Mañjuśrī images in the Wutai region is a new convention, entirely without precedent. Examining the statues closely, we realize that the dress consists of three garments from outside to inside: a cloud collar (

yunjian 云肩), a wide-sleeved shirt, and a long-sleeved inner garment visible underneath the wide sleeves of the shirt. Together, these garments give rise to a dramatic visual: an ornate belt cinches the wide-sleeved shirt laterally at waist level, producing swirling folds above and below the waistline; the wide sleeves shoot up in emphatic lines, creating flame-like patterns at both elbows; the elaborate collar completes the pomp of the dress by emphasizing the upper contours of Mañjuśrī with its elegant, cloud-like hems.

14 This style of dress, and the theatrical visuals it creates are highly unusual among the sartorial conventions of bodhisattva images in the Tang period. Bodhisattva images of this period generally bare their upper torsos except for a sash that crosses over their chest diagonally (see for instance the leftmost bodhisattva in

Figure 6) or sometimes an inner garment that also reveals much of the chest above its diagonal upper hem (see

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). They wear skirts, and scarves cover their shoulders and descend in undulating curves at both sides of the body. The special outfit for the above-discussed Mañjuśrī images of Mount Wutai is therefore not of the convention of the time. Surveying the history of dress in bodhisattva images reveals that this dress also lacks precedent in earlier periods.

15 It is a new mode of dress that was developed in the eighth century.

This new mode of dress, moreover, was reserved exclusively for the Mañjuśrī image associated with Mount Wutai from the eighth to the eleventh centuries.

16 In the Wutai area, all the other bodhisattva images in Nanchan and Foguang Monasteries that accompany the appearance of Mañjuśrī keep to the conventional costume for Tang-period bodhisattvas, regardless of whether they were the great Bodhisattva Samantabhadra or attendant bodhisattvas of a lower stature (see

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

17 Expanding our search to sites such as Sichuan and Dunhuang, where a rich trove of Tang Buddhist images is preserved, we came to the similar observation that bodhisattvas at that time—Samantabhadra, Avalokiteśvara, or bodhisattvas representing their generic type—are all dressed in the traditional attire consisting of a sash/inner garment, a skirt, and scarves.

18Two images explicitly referencing the true appearance of Mañjuśrī at Mount Wutai, though found outside the Wutai area, further confirm the iconographic significance of the dress to the True Visage Mañjuśrī. One is from a dozen woodblock prints unearthed from Dunhuang, made between 944 and 974 (

Figure 2). The other is also a woodblock print in the collection of Daigoji, Japan (

Figure 8). We shall examine them both in turn.

Figure 2 shows the bodhisattva Mañjuśrī accompanied by the Khotanese King and the boy Sudhana. All past scholarship links it to the new-model Mañjuśrī mural found in Cave 220 (

Figure 1) due to their broad similarities.

19 However, close observation reveals that the bodhisattva Mañjuśrī in

Figure 2 departs from the depiction in

Figure 1 in terms of his attire. While the dense folds make it less obvious how the bodhisattva is dressed, the flame-like patterns at both elbows clearly indicate the layer of the wide-sleeved shirt, revealing the long-sleeved inner garment underneath. The double-lined band of an inverted V-shape at waist level indicates the belt, while the spiraling details close to the neck the cloud collar. The bodhisattva in

Figure 2 is dressed in the special set of garments typical of the Mañjuśrī image associated with Mount Wutai. What is remarkable about this woodblock print is the dedicatory verse below the image, which identifies the image as “the true appearance of Mañjuśrī as he manifested in Mount Wutai”. This identification unambiguously links the image to the True Visage Mañjuśrī at Mount Wutai and confirms the special mode of dress as a defining feature of this iconographic type.

Figure 8 provides an even more transparent example attesting to the iconographic significance of the special dress, as the details of bodhisattva Mañjuśrī’s attire are rendered very clearly, allowing us to see the cloud collar and the flame-like sleeve details. The bodhisattva’s entourage is expanded, including an elderly man and a junior monk in addition to the standard pair of the boy Sudhana and the Khotanese King. The elderly man and the monk reference another famous episode that purportedly took place on Mount Wutai,

20 while the five peaks in the background unambiguously set the appearance of the saintly quintet in Mount Wutai. While the print was made in the twelfth century, the unmistakable visual references to Mount Wutai, as well as its long-known epithet “Mañjuśrī of Mount Wutai”, have led many scholars to speculate that this woodblock print was based directly on a template brought back to Japan by Ennin from Mount Wutai.

21

Figure 2.

Image of the True Visage Mañjuśrī, woodblock print, Mogao Cave 17, Dunhuang, ca. 944–974. British Museum 1919, 0101, 0.238. Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 2.

Image of the True Visage Mañjuśrī, woodblock print, Mogao Cave 17, Dunhuang, ca. 944–974. British Museum 1919, 0101, 0.238. Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 3.

Icon of True Visage Mañjuśrī, Nanchan Monastery, Mount Wutai, 782. Photograph by the author.

Figure 3.

Icon of True Visage Mañjuśrī, Nanchan Monastery, Mount Wutai, 782. Photograph by the author.

Figure 4.

Icon of True Visage Mañjuśrī, Great Buddha Hall, Foguang Monastery, late eighth to the ninth century. Photograph by the author.

Figure 4.

Icon of True Visage Mañjuśrī, Great Buddha Hall, Foguang Monastery, late eighth to the ninth century. Photograph by the author.

Figure 5.

Icon of True Visage Mañjuśrī, Hall of Mañjuśrī, Foguang Monastery, 1137. Image from (

Sun 2007, pl. 40).

Figure 5.

Icon of True Visage Mañjuśrī, Hall of Mañjuśrī, Foguang Monastery, 1137. Image from (

Sun 2007, pl. 40).

Figure 6.

Icon of Samantabhadra and attendants, Great Buddha Hall, Foguang Monastery, late eighth to the ninth century. Photograph by the author.

Figure 6.

Icon of Samantabhadra and attendants, Great Buddha Hall, Foguang Monastery, late eighth to the ninth century. Photograph by the author.

Figure 7.

Icon of Samantabhadra riding an elephant, Nanchan Monastery, Mount Wutai, 782. The attendants are seen to the left of Samantabhadra. Photograph by the author.

Figure 7.

Icon of Samantabhadra riding an elephant, Nanchan Monastery, Mount Wutai, 782. The attendants are seen to the left of Samantabhadra. Photograph by the author.

Figure 8.

Mañjuśrī riding a lion surrounded by four attendants with Five Sacred Peaks of Mount Wutai in the background. Woodcut print, 12th century. Image from

Nishikawa et al. (

2001), Daigoji taikan, vol. 2, 113.

Figure 8.

Mañjuśrī riding a lion surrounded by four attendants with Five Sacred Peaks of Mount Wutai in the background. Woodcut print, 12th century. Image from

Nishikawa et al. (

2001), Daigoji taikan, vol. 2, 113.

The consistency in the special dress ensemble for images of Mañjuśrī on Mount Wutai, or those based on prototypes from Mount Wutai, cannot be merely accidental. It is clear that this detail was not a random fashion choice but a vital aspect of the iconographic configuration of the True Visage Mañjuśrī at Mount Wutai.

4. Understanding the Special Ensemble in the Wutai Context

The special ensemble is without precedent in the history of Buddhist attire, and it does not have any basis in Buddhist sutras or commentaries. In drawing on past studies on the Chinese fashion history, this section locates the constituent dress pieces in the traditional Chinese dress system and attempts to interpret their cultural and religious significance in the context of the development of the sacred mountain cult at Wutai in order to illuminate understudied aspects in this milestone event of Chinese Buddhism.

The most visually intriguing aspect of the special ensemble is the shirt, with its flame-like sleeve details. Some scholars suggest that it may have been a

kedangyi (a shirt covering the chest and the back, (衤蓋)襠衣) based on the notes accompanying deity images wearing a similar shirt and elbow details in medieval Japanese manuals for Buddhist rituals.

22 Although the Japanese manuals do not provide further explanations about the

kedangyi, references to

liangdangyi (a variant name of

kedangyi, 两襠衣) are found in Chinese sources, which explain it as traditional Chinese attire first developed in the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589) to be worn under armor or directly as a top in ritual occasions by aristocrats (

Chen 2012, pp. 19–34). Archaeological materials supplement the textual explanation, as we observe that Empress Wenzhao, consort of Emperor Xiaowen of the Northern Wei dynasty (467–499), wore a shirt with just such elbow details (though rendered more petal- than flame-like) in a Buddhist offering procession as depicted in the center of the relief panel from the Longmen Grottoes, Henan (

Figure 9).

Following its usage in actual life, the

kedangyi began to see limited application in the Buddhist visual culture from the eighth century. It appears most often on Vaiśravaṇa, the Heavenly King of the Northern Direction (

Figure 10),

23 while celestial dancers and minor bodhisattvas making offerings to major deities are also sometimes seen with the flame-like patterns around the elbows (

Figure 11). Given the textual and pictorial evidence, it seems that the shirt worn by Mañjuśrī is also a

kedangyi/liangdangyi, a garment that was part of the standard dress of Chinese warriors and noble elites.

Layered atop the

kedangyi is the cloud collar. Widely known as a popular woman’s accessory in the Ming and Qing dynasties, recent research has shown that in its early history, cloud collars were likely used as an accessory for divinities in the traditional Chinese pantheon. Many scholars have noted that from the Han (202 BCE–220 CE) to the Northern and the Southern Dynasties (420–589), traditional Chinese deities such as Fuxi and Nvwa, Queen Mother of the West and celestial beings are often depicted wearing a collar (

Figure 12) (

Li 2000, p. 46;

Gao 2005;

Huang and Meng 2021). This collar is not seen on mortals, suggesting it to be a symbol of the divine. Scholars further propose that the collar was derived from the imagery of winged or feathered beings, owing to the Chinese imagination of the divine as being able to mount the clouds and wander unchecked over the universe (

Gao 2005).

In entering the Sui and Tang dynasty, the collar motif became appropriated into Buddhist paintings for a select few high-ranking celestial beings. As an example,

Figure 13 is a detail of a Sui dynasty mural showing a celestial figure (commonly identified as Lakṣmī) attired in a very intricate collar. It is sewn together with multiple pieces of cloth with the lower end of each piece cut into an inward concave arc, creating an undulating hem. The addition of the cloud collar to high-ranking female Buddhist divinities in the Sui and Tang period, as convincingly argued by Gao Yang, was likely inspired by the tradition of accessorizing local deities with the collar motif.

24 This originally sacred attire began to be used in wider contexts in the tenth century, until it became completely secularized as a popular accessory for women of both high and low social status in the Ming and Qing periods (

Huang and Meng 2021).

Past studies on the two clothing pieces reveal their Chinese origination and sacred cultural association. We can understand that the implied sacredness of the cloud collar would add to the transcendent aura of Mañjuśrī, while the visual pomp and ritual association of the kedangyi may serve to glorify the bodhisattva. Yet, it is still insufficient to fully elucidate important questions such as who decided on this fashion change as well as its deeper levels of significance in a new representation of Mañjuśrī claiming an unprecedented level of authenticity. Although it is difficult to answer these questions with certainty due to limited sources, the next section makes some preliminary suggestions that may at least point to the complex mechanism and dynamics involved in the formulation of the True Visage Mañjuśrī and the cult of Mount Wutai.

4.1. Localizing Mañjuśrī at Mount Wutai

While dressing Buddhist figures in Chinese attire is not unprecedented—the sixth century already saw the adoption of a sinicized mode of dress for buddhas and bodhisattvas, not to mention the aforementioned application of the kedangyi to Vaiśravaṇa and celestial dancers—the return of Xuanzang from India in 645 spurred an Indianizing trend in the development of Tang Buddhist art. Bodhisattva images, especially, reverted to the Indian style of dress, with bare upper torsos adorned with luxurious jewelries, sashes, and scarves. The choice of traditional Chinese costume for a major bodhisattva deity, the great bodhisattva Mañjuśrī, and for himself alone against the broad Indianizing development of Tang Buddhist art thus constitutes a salient anomaly.

The anomalous fashion choice for the True Visage Mañjuśrī may be explained against the history of Mount Wutai and the complex development of domesticating and localizing the sacred presence of a foreign deity in a Chinese site. As various scholars have argued, already by the second half of the sixth century, there were tentative associations identifying Mount Wutai with Mount Clear and Cool, the sacred abode of Mañjuśrī located in the northeast of Jambudvipa as described in the

Flower Garland Sutra, which was first translated into Chinese around 420.

25 The identification of Mount Wutai with the abode of Mañjuśrī, however, began to gain real strength in the late seventh century and was officially confirmed in the first decade of the eighth century. Translated in 710 by Bodhiruci (672–727), a Buddhist master of south Indian origin, the text was titled the

Scripture of Mañjuśrī’s Dharma Treasure-Store Dhāraṇī (Wenshu shili baozang tuoluoni jing). This sutra is the first to assert explicitly that the abode of Mañjuśrī, Mount Clear and Cool, is located in the Chinese territory. Presenting it as the words of Sakyamuni, the sutra states: “After I have passed away, in this Jambudvīpa in the northeast quarter, there is a country named Mahācīna [i.e., Great China]. In the country there is a mountain named Five Peaks, in which the youth Mañjuśrī will roam about and dwell, expounding the Dharma at the mountain for sake of sentient beings.”

26 The reference to the five peaks in the sutra—the most prominent topographic feature of Mount Wutai–was likely intentional as Bodhiruci may have played along with the booming cult of Mount Wutai and Mañjuśrī, for which even Empress Wu was an enthusiastic supporter. In any regard, the translation of the new sutra is strategic in presenting a crucial, scriptural basis confirming the sacred presence of a prominent Buddhist deity in China.

Culminating the complex process of establishing the presence of Mañjuśrī in Mount Wutai is the creation of an iconic image at the Great Huayan Monastery, believed to transmit the true visage of Mañjuśrī. The origin story of this icon has been discussed earlier, as is recorded in the diary of Ennin. The story narrates how a skilled master keeps failing at making an image of the Great Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī six times and succeeded, finally, when the bodhisattva himself manifested his true form to allow his elusive presence to become materialized into a splendid icon. While Ennin’s diary does not provide specific historical details on this legendary occurrence, the story was placed right after the translation of the new sutra in 710 in the era of Jingyun (710–712) in tenth- and eleventh-century accounts such as Dunhuang manuscript s529v and

the Extended Records.

27 Unlike tales of divine traces and numinous marvels, the creation of an iconic image believed to transmit the true visage of Mañjuśrī, with the help of the bodhisattva himself, marked a symbolic moment as the amorphous presence of the divine was finally, physically and visually, located in Mount Wutai.

28But another of the icon’s significant functions, not paid adequate attention to in past studies, is to visualize the Mañjuśrī who dwells at Mount Wutai. In order to really move a major Buddhist deity’s abode from the Buddhist cradle in India to a mountain located in the northwest of China, it is not sufficient to establish Mount Wutai as merely a sacred place where Mañjuśrī ’s manifestations can be sighted. Rather, Mount Wutai needs to be reconfigured as the sacred place where Mañjuśrī permanently resides. The need to visually establish that distinction—implicit in this process is the competition with India—may explain the unusual choice of the traditional Chinese costume for Mañjuśrī in his true form. In the Tang period, Mañjuśrī was the only bodhisattva whose abode was believed to be a Chinese site. Meanwhile, more than just coincidental, only Mañjuśrī was dressed in the traditional Chinese costume while all other bodhisattva images, including his companion Samantabhadra, were dressed in the Indian style following the broad Buddhist artistic development of the Tang period. The sinicized dress for Mañjuśrī, therefore, could be understood as an effective visual device asserting the primacy of his resident identity over his place of origin. It dovetails with the newly translated sutra and visually corroborates and strengthens the notion that “the youth Mañjuśrī will roam about and dwell at the (Wutai) mountain”. The choice of traditional Chinese attire may have constituted a strategic move to claim the Chinese site of Mount Wutai for the full entitlement to Mañjuśrī’s sacrality.

4.2. The Agency of the Individual Monastery

The Sinicization theory may account for the choice of traditional Chinese clothing for the True Visage Mañjuśrī, but could it be possible that the

kedangyi and cloud collar were chosen not, or at least not entirely, because of their ethnic association? The Sinicization model, or its reverse model based on acculturation, has long shaped research on Chinese Buddhist art. But as scholars have noted, these generalized models, while providing useful structures, run the risk of oversimplifying the complex development of actual scenarios, blinding us to practical issues and local interests that may have also interacted with decisions of artistic forms.

29Local interests exist in the fact that the site of Mount Wutai was a dynamic power network consisting of multiple local sites and various monasteries. Although miracle tales related to Mount Wutai collectively defined and sanctified the Wutai region as a whole, each monastery in the mountain region was a distinct locus, wherein its specific history, memory, and legendary tales would coalesce to create layers of evocations peculiar to that locus (

Lin 2014, p. 161). These evocations helped monasteries to assume different roles and positions in the sacred landscape of Mount Wutai, and those roles and positions were in constant flux rather than fixed in history, subject to the influence of imperial patronage, sectarian competition, legendary tales, and visual monuments.

30The recognition of local competition within the Wutai region enables us to consider the problem of the True Visage Mañjuśrī’s creation from a different perspective. The origin story of the True Visage icon was set in the Great Huayan Monastery. More than coincidently, the tale “Bodhisattva Manifesting His Body as a Poor Lady”, which later joined in the narrative explaining the configuration of the True Visage image, was also set to have occurred in the Great Huayan Monastery. Indeed, the tale “Bodhisattva Manifesting His Body as a Poor Lady” and the origin story of the True Visage icon were the two most widely circulated miracle tales associated with the Great Huayan Monastery.

31 Clearly, the True Visage image was crucial for the creation of evocations specific to the Great Huayan Monastery. While the True Visage icon was venerated as a tangible, perceivable vision of the divine’s elusive presence at Mount Wutai, it helped to establish the centrality of visions attained at the Great Huayan Monastery among the various reported sightings of divine presence at Mount Wutai, which in turn contributed to consolidating the position of the Great Huayan Monastery as one of the centers of Mount Wutai.

The creation of the True Visage icon very likely referenced, and visually enriched, the memory and history surrounding the Great Huayan Monastery. However, there is a material lacuna for us to pursue the exact role and agency of the Great Huayan Monastery in the formulation of the True Visage Mañjuśrī. It is also unclear if the special ensemble was part of the visual device chosen by the clergy of the Great Huayan Monastery to anchor people’s imagination of the saintly figure in the monastery. All that information is, unfortunately, lost to time.

4.3. The Esoteric Association

The potential esoteric association of this dress ensemble opens a path for considering its application to the True Visage Mañjuśrī. The

kedangyi, in particular, is commonly applied to esoteric deities. For instance, the

scroll from the Compendium of Iconographic Drawings, a twelfth-century encyclopedia of esoteric Buddhist iconography, has Prajñāpāramitā (an esoteric deity embodying transcendental wisdom) (

Figure 14) and spiritual guardians depicted as wearing a

kedangyi. Indeed, historians of esoteric art have been the first to pay attention to this special clothing feature. In particular, its origin and incorporation history into the esoteric iconographic repertoire have been the subject of much debate.

32 I have argued that the

kedangyi and cloud collar originate in traditional Chinese costume, but their esoteric connections need to be discussed in order to provide balanced consideration to both their applications to the True Visage Mañjuśrī and esoteric deities. Could it be that this special ensemble was incorporated into the Mañjuśrī image due to an esoteric connection? This is not entirely far-fetched with Amoghavajra (705–774) serving as an important connective figure linking Mañjuśrī at Mount Wutai and esoteric Buddhist art. As is well known, Amoghavajra was a legendary figure in the eighth-century Chinese Buddhist development and served Emperor Xuanzong (r. 712–756), Suzong (5. 756–762), and Daizong (r. 762–779) as a close council. In the last two decades of his life, he turned to the cult of Mañjuśrī and Mount Wutai and helped Mañjuśrī reach a more elevated status than any other esoteric deity.

33 Important acts that Amoghavajra had taken to advance the cult of Mañjuśrī include the translation of many esoteric sutras surrounding this deity, the petition to build the Jin’ge Monastery at Mount Wutai and to install an image of Mañjuśrī at every monastery in the empire.

34Amoghavajra’s fervor toward Mañjuśrī opens up the possibility that he took an interest in the appearance of the esoteric Mañjuśrī, which compels us to first reconsider whether the Wutai Mañjuśrī images discussed in this paper—the ones from the Nanchan and Foguang monasteries—were copies after the model conceived by Amoghavajra (if there ever was such a thing) or the True Visage image at the Great Huayan Monastery. Ennin’s diary provides a clue by affirming that the icon at the Great Huayan Monastery was “the prime icon after which all Mañjuśrī images on Mount Wutai were modelled”.

35 This means that there was only one model (the True Visage icon at the Great Huayan Monastery), rather than two, for Mañjuśrī images at Mount Wutai. Ennin’s record further documents the Mañjuśrī icon at the Jin’ge Monastery, an esoteric ritual space designed per the vision of Amoghavajra. It is a “Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī, who rides a blue lion, is gilded and his countenance and presence is unmatchably serene.”

36 If Amoghavajra had intervened in the visual configuration of Mañjuśrī’s image, it was most likely based on esoteric sutras. The textual record specifies that Amoghavajra requested the six-syllable Mañjuśrī, a form of Mañjuśrī based on esoteric sutras, be installed as the main icon for the Mañjuśrī Pavillion of the Great Xingshan Monastery in Chang’an.

37 The Mañjuśrī Pavillion was constructed under the petition of Amoghavajra in 772 for the purpose of state protection. Tang emperor Daizong appointed himself to be the master of the pavilion, testifying to its very privileged status. The Great Xingshan Monastery was therefore the most important dharma field for the lineage of Amoghavajra. Although that icon had long perished together with the monastery site, sutras inform us that the six-syllable Mañjuśrī should take the shape of a young boy, seated on a lotus pedestal rising from a pond instead of the lion vehicle. He should wear the standard bodhisattva attire, have the right hand in the wheel-turning mudra and the left hand horizontal with palm facing up. Avalokiteśvara and Samantabhadra should flank him on either side (

Figure 15). Noting the difference between the six-syllable Mañjuśrī and the Mañjuśrī image at Mount Wutai, Zhang Shubing speculates that the Mañjuśrī statue that Amoghavajra petitioned to install in all monasteries in the empire was also a six-syllable Mañjuśrī, as the petition mentions the Mañjuśrī needed to be attended by Avalokiteśvara and Samantabhadra.

38 Clearly, Amoghavajra preferred the six-syllable Mañjuśrī when he was free to intervene with the formal decision of the Mañjuśrī image. The main icon in Jin’ge Monastery, riding on a blue lion as Ennin recorded, was most likely based on the familiar True Visage icon developed in the earlier history of Mount Wutai at the Great Huayan Monastery.

As it is safe to conclude that the Wutai images discussed in this paper transmit the original True Visage image of Mañjuśrī developed at the Great Huayan Monastery, we can then evaluate whether the incorporation of the special dress ensemble to the True Visage Mañjuśrī referenced any esoteric connection. Historically, the Great Huayan Monastery was not an esoteric site; hence, we are missing the rationale for it to adopt any esoteric iconography. Chronologically, the creation legend of the True Visage Mañjuśrī places the event in the Jingyun era (710–712), which is decades earlier than the introduction of Tang esoteric Buddhism in the latter half of the Kaiyuan era (713–741). If the date in the Jingyun era is reliable, then the formulation of the True Visage Mañjuśrī was earlier than the flowering of esoteric Buddhist philosophy and art, precluding the possibility that the fashion detail’s incorporation into the True Visage Mañjuśrī had any esoteric connection. Unfortunately, the historical accuracy of the Jingyun era cannot be fully confirmed as it is recorded only in tenth- and eleventh-century accounts, leaving it possible for the date to have been a fictive embellishment added in retrospect.

Imann Lai (

2023) notices that the

kedangyi was applied most often to Prajñāpāramitā in the earliest extant esoteric visual materials.

39 She also notes that Prajñāpāramitā appears as

samaya (the symbolic form such as vajra-mallet and jewel) in eighth-century sources but became anthropomorphized in ninth-century accounts.

40 Her comparison of eighth- and ninth-century anthropomorphized depictions of Prajñāpāramitā brings attention to one late eighth-century example of the bodhisattva attired in the standard bodhisattva dress of the Tang period, while all the other instances, datable to the ninth century, have Prajñāpāramitā wearing a

kedangyi (for instance,

Figure 16). The late eighth to the ninth century, therefore, appears to be a crucial period for the visual codification of Prajñāpāramitā both in anthropomorphized form and in a

kedangyi. In any case, the late eighth and ninth century is definitively later than the formulation of the True Visage Mañjuśrī.

There may be an earlier example of Prajñāpāramitā, which comes from a group of eleven fragmented esoteric Buddhist statues discovered from the site of the former Tang dynasty Da Anguo Monastery in 1959. They are dated to between the mid-eighth and the early ninth century on stylistic grounds (

Chang 2018). Among the eleven icons, two bodhisattva statues were found alongside other images of Buddha and Wisdom Kings. One of the two bodhisattva images, identified as Avalokiteśvara based on his royal ease posture, is attired in the standard Tang bodhisattva mode, with the upper torso bare and a skirt for the lower body. The other bodhisattva image holds a lotus stem topped with a sutra casket in his left hand, while his right hand is broken off at the wrist, but it probably held a sword of truth originally (

Figure 17). He is most often described as representing Mañjuśrī, owing to the attributes held in his hand. Alternatively, it has also been suggested that he could have been Prajñāpāramitā, as the

Instructions for the Rites, Chants, and Meditations of the Prajñāpāramitā Dhāraṇī Scripture for Humane Kings Who Wish to Protect Their States (Renwanghuguo bore boluomiduo jing tuoluoni niansong yigui) also describes Prajñāpāramitā as holding a sutra casket.

41 In any case, this bodhisattva is attired in the same way as the True Visage Mañjuśrī at Mount Wutai, displaying the flame-like sleeve details and a cloud collar with wavy hems. The ambiguity of identification between Prajñāpāramitā and Mañjuśrī could very well be the reason why the

kedangyi was appropriated for Prajñāpāramitā. Both bodhisattvas represent wisdom in the system of Buddhist divinities, and both have similar iconographic descriptions in sutras. Although the present scarcity of information precludes a definitive answer, it must not be mere coincidence that Mañjuśrī and Prajñāpāramita happen to be the two bodhisattvas that became associated with the

kedangyi at the earliest time and went on to be rendered in a

kedangyi most often throughout Buddhist visual history. Given the present information, it is my conjecture that the attire in the most widely recognized representation of Mañjuśrī was appropriated for Prajñāpāramita due to the similar character of the two bodhisattvas. Starting from the esoteric deity Prajñāpāramitā, the special dress ensemble then gained wider reception and became applied to an extended esoteric pantheon in the later centuries.

The above attempts to understand the two clothing features in the context of the cult of Mount Wutai have unfortunately remained largely speculative, owing to the present scarcity of materials. But the identification of the special attire for the True Visage Mañjuśrī opens up a path of interpretation that has remained relatively unnoticed. This fashion detail provides a chance to dig deeper into the multifaceted development of the True Visage Mañjuśrī and the cult of Mount Wutai, as well as into the complicated connection between the Mañjuśrī image and esoteric Buddhist art. Greater attention to these two clothing features from across disciplinary sub-strands and through the discoveries of new materials in the future may bring renewed thinking to the cult of Mañjuśrī and contribute to a more fine-grained understanding of Chinese Buddhist art.

5. Conclusions: True Visage as Rooted in Contextualized Imagination Rather Than Formal Precision

Finally, the iconographic re-evaluation of the True Visage Mañjuśrī offers an opportunity to revise our conception of auspicious images and their replication, to be taken up as the conclusion of this article. The new iconographical insight attained from this study calls into question the conventionally accepted identification between the new-model Mañjuśrī with the True Visage Mañjuśrī developed at Mount Wutai. Although it now becomes clear that such Dunhuang creations of the new-model Mañjuśrī are missing the essential features that defined the Mount Wutai originals, their authenticity and geographical specificity still stood in the eyes of the Dunhuang locals. The cartouche next to the Mañjuśrī image in the corridor of Mogao Cave 220 explicitly identifies it as the “True Visage of the Great Sage Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī”, which provokes the following question: are these Dunhuang images misrepresentations or intentional transformations of the original True Visage image from Mount Wutai? This leads to a more important line of further questions: How does formal precision affect the religious efficacy of an auspicious image? What does it mean to “copy” a sacred image and who are the active agents in deciding what is an authentic “copy”? The materials surrounding the True Visage Mañjuśrī present an opportunity to pursue these questions and reflect upon the traditional formal approach of studying auspicious images.

Misrepresentation due to the Dunhuang community’s temporal and geographical separation from the True Visage icon’s historical unfolding may be an initial response, but Buddhist contacts between Dunhuang and Mount Wutai were largely frequent and vigorous despite the temporary setback due to political turmoil from the mid-eighth century until the 920s (

Rong 1987). Materials such as the woodblock print in

Figure 2 and silk painting EO3588 confirm that tenth-century Dunhuang artisans did have access to accurate depictions of the True Visage image invented at Mount Wutai, but the special dress of the True Visage Mañjuśrī associated with Mount Wutai appeared not to have had good reception. Almost all mural paintings in Dunhuang render Mañjuśrī in the standard bodhisattva attire.

42 The special dress ensemble was rarely appropriated in Dunhuang other than for high-level celestial beings. Instead, Dunhuang artisans turned to the Khotanese King as the crucial indicator guaranteeing the authenticity of the Mañjuśrī image by regularly including this figure in the new model of the deity’s pictorial representation.

The shift of focus from the special dress to the Khotanese King was more likely intentional than accidental. After regaining Chinese control from Tibetan rule in 848, Dunhuang became ruled by powerful local clans. The tenth-century ruling family, the Cao family, forged a strong alliance with its neighboring kingdom Khotan through marriage, ushering a period of vigorous travels and cultural communications between Khotan and Dunhuang. The Khotanese themes, including portraits of Khotanese royal members, Khotanese auspicious images, Khotanese divine protectors, and the Khotanese sacred mountain Ox head, received a boost during this period.

43 In particular, among the various auspicious images found in tenth-century Dunhuang, scholars have counted more than one third of the total number that are clearly connected with Khotan and its mythology. Sha Wutian relates the popularity of Khotanese themes in Dunhuang Buddhist imagery to the context of close Dunhuang–Khotan interconnections in the tenth century (

Sha 2005). This is a very insightful observation, but to read Buddhist artistic phenomena solely in the framework of diplomatic contacts and political agendas might signal a missed opportunity to explore deeper into the religious sensitivities of tenth-century Dunhuang. While the centrality of Khotan in Dunhuang auspicious imagery helped to strengthen the political alliance between the two regions, as Sha rightly points out, it must have also fostered and reflected the Dunhuang locals’ sacred imagination of Khotan. Khotan was perceived as not only a reliable ally, but also a Buddhist stronghold and a cradle of auspicious imageries. The shift of focus from the special dress ensemble to the Khotanese King in representing Mañjuśrī’s true form may have come about in this local religious milieu that was keen on associating auspicious imagery with Khotan. The discrepancy between the images representing Mañjuśrī’s true visage in Dunhuang and Mount Wutai exemplifies how, in the transmission of auspicious images, formal precision gave way to local religious sensitivities.

The visual emphasis on the Khotanese King in the representations of Mañjuśrī’s true visage being a Dunhuang adaption would help to explain the absence of the Khotanese King in the ninth-century version of the story “Bodhisattva Manifesting His Body as a Poor Lady” as recorded by Ennin. It is very likely that the Khotanese King was assimilated into the literary tradition only after it became widely recognized as a vital feature asserting the authenticity of a new vision of Mañjuśrī in the tenth century. In the Extended Records compiled in 1060, not only is the Khotanese King a major protagonist in the more developed version of the tale “Bodhisattva Manifesting His Body as a Poor Lady”, but he also appears in another account as verification of the authenticity of one sighting of Mañjuśrī purported to have occurred in the tenth century:

Master Ziyong of Shuozhou traveled to Mount Wutai again in the Tianhui era (925) with his disciple Master Shi and one hundred people. … One day they visited the Great Huayan Monastery. Suddenly, they saw at the side of the monastery an auspicious cloud arising from the east and coming, surrounded by five-coloured clouds. Soon, from the cloud appeared the Great Sage Mañjuśrī seated on a lotus lying on the lion’s back. Sudhana led the way and the Khotanese King tamed the lion, followed by Buddhapalita. The dragon mother and the five dragon kings all bowed to them. They all wore strange clothes and the transformation was so spectacular. Witnesses numbered more than one thousand.

44

The rise to centrality of the Khotanese King in the literary tradition is most logically interpreted as reflecting the increasing significance of the Khotanese King in the representation of Mañjuśrī’s true visage. A Central Asian lion tamer may have been part of the True Visage Mañjuśrī invented at Mount Wutai in the eighth century, but he probably did not assume any significant functional role as there exists no compelling reason to include him in the context of either the cult of Mañjuśrī or Mount Wutai. Chen Suyu propounds a convincing theory that the choice by Mount Wutai artisans to replace the South Asian lion tamer with a Central Asian lion tamer in the representation of Mañjuśrī’s true visage was to better accord with historical reality (

Chen 2014). Lions were conventionally offered as tribute by Central Asian kingdoms, while elephants were offered as tribute by South Asian kingdoms. Citing evidence in secular art of the common pairing between a Central Asian King and a lion, Chen argues that the choice of a Central Asian King as the tamer for the lion of Mañjuśrī was an attempt to better reflect historical reality and bolster the glory of Tang China as the center of an expansive tributary system. Chen further notes that the depiction of the Central Asian King in the True Visage Mañjuśrī followed the generic image of a Central Asian figure. The identification of this generic Central Asian King as the King of Khotan most likely occurred in Dunhuang rather than Mount Wutai, as the present evidence suggests.

45 The attendant figures of the Mañjuśrī image in the Mañjuśrī pavilion at Mount Hiei in Japan, which was founded at the wish of Ennin, were recorded as mere “attendant figure (

shizhe 侍者)” and “lion tamer (

shizi yuzhe 狮子御者)”, indicating that the attendants were not necessarily recognized as boy Sudhana and King of Khotan by the time of Ennin’s visit to Mount Wutai.

46 The earliest explicit identification of this Central Asian figure as the Khotanese King was found at Mogao Cave 220, dated to 925, which predates, by more than one century, sources with authorship related to Mount Wutai that confirm the Khotanese King to be part of the entourage accompanying the manifestation of Mañjuśrī.

The reconsideration of what we know points to a new interpretative possibility based on a diachronic development of both the literary and the visual tradition associated with Mañjuśrī’s true form. Though the True Visage Mañjuśrī was originally conceived at Mount Wutai, it received a new interpretation in Dunhuang, which in turn interacted with the existing mythologies to create revised understandings surrounding this miraculous vision of the bodhisattva at Mount Wutai and its representation.

Studies on the replication of famous miraculous images in Japan suggest that the investment of divine power in a replica required only the successful copying of the most salient features of the miraculous original rather than strict adherence to formal exactitude (

Nedachi 2016, p. 41). Yet, what constitute the most salient features is subject to the receptors’ imagination and interpretation. Choi’s study reveals such formal latitude as displayed in the creation of the auspicious Mahābodhi Buddha images (

puti ruixiang 菩提瑞像) due to the local reimagination of the prototype (

Choi 2015). She notes that the original Mahābodhi Buddha image in India did not have lavish jewelry as part of the iconography. Jewelry were separate ornaments added onto the statue as offerings by reverent worshippers. In China, however, such jewelry became an integral part of the auspicious Mahābodhi images’ iconography because the medieval Chinese found a bejeweled statue befitting their romantic idea of a foreign statue. The shift of focus to an external feature of the auspicious Mahābodhi image’s Indian prototype as discussed by Choi finds parallel in the case of the True Visage Mañjuśrī. What mattered was not what really constituted the defining features of the prototype in its original context. Rather, it was what the receptors

imagined to have constituted the defining features in their context. Material aspects such as the literary production of miraculous tales and visual prototypes considered to have brought from sacred origins help to create or strengthen the imagination of an image’s religious efficacy and authenticity. Yet, this imagination is not fixed in eternity once tied to a set of material anchors. It is a contextualized activity subject to reimagination and transformation by local sensitivities across different temporal–spatial realms, and different local imaginations may encounter and interact to produce further altered understandings. While the traditional formal approach to auspicious images—tracing the form of the original and the route of transmission—would still prove essential, approaching the notion of auspicious images as a dynamic symbol emerging from open, mobile contexts rather than as a fixed product of a static system brings to light more nuanced understandings of inter-regional Buddhist transmission.