Abstract

This paper aims to observe, contextualize, and analyze the multifaceted religious fungal foundations of Moscow Conceptualism within the context of Slavic and European esoteric mythological praxis. By unveiling the thematic basis of their transgressive spiritual endeavors, this study seeks to enhance our comprehension of this artistic and literary movement in the Western world. Besides exploring the erotic aesthetics associated with mushrooms, significant attention is devoted to various flies, as the biological vitality of the mukhomor (‘fly agaric’ or amanita muscaria) is inconceivable without them. Moscow Conceptualist visionaries, including Andrey Monastyrsky, Ilia Kabakov, Elagina and Makarevich, and the Mukhomor Moscow collectives, along with their no less famous colleague from Leningrad, Sergey Kuriokhin, emerge not only as artists but also as literary innovators. They seamlessly integrate advancements from the realm of art, giving rise to a novel form of religiously symbiotic semiosis. Consequently, the traditional boundaries between diverse art forms become blurred, marking a distinctive characteristic that aligns with international contemporary avant-garde aesthetics.

“The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and all science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer pause to wonder and stand rapt in awe, is as good as dead: his eyes are closed. The insight into the mystery of life, coupled with fear, has also given rise to religion. To know what is impenetrable to us really exists, manifesting itself as the highest wisdom and the most radiant beauty, which our dull faculties can comprehend only in their most primitive forms—this knowledge, this feeling is at the center of true religiousness.”Albert Einstein (1954).

1. Preliminary Remarks

In the following discussion1, I delve into the intricate intellectual roots of the ‘mushroom theme’, or more precisely, the concept of a ‘mushroom esoteric religion’ within the multifocal realms of Moscow Conceptualism.2 This thematic exploration is vividly showcased through the works of numerous influential figures and collectives from the tumultuous decades of the 1970s and 1980s. This recurrent motif among several visionary artists can be aptly likened to the construct of an esoteric religious ideology, embodying layers of hidden meanings and spiritual connotations. It serves as a symbolically rich thread weaving through their artistic expressions, inviting interpretations that transcend the surface narrative. At the core of this phenomenon lie the Moscow Conceptualists, who emerged as the vanguard of intellectualism and cultural exploration within Soviet society. They constituted a distinctively erudite and cultivated subset, endowed with a depth of knowledge and insight often inaccessible to the broader provincial populace. Their privileged access to information, combined with their relentless pursuit of intellectual inquiry, afforded them a unique perspective that permeated their artistic endeavors. Through their oeuvre, they not only challenged the constraints of the prevailing socio-political landscape but also illuminated the clandestine realms of thought and belief, inviting viewers to engage with concepts beyond the ordinary (Nicholas 2024; Groys 2013; Eşanu 2013; Degot and Zakharov 2005; Nicholas 2022; Jackson 2016; Ioffe 2013, 2016, 2022). In essence, the ‘mushroom esoteric religion’ of Moscow Conceptualism (Ioffe 2020) transcends mere artistic expression; it embodies a profound exploration of the human condition, spirituality, eroticism, and more generally, the boundaries of perception. It stands as a testament to the power of creativity to transcend limitations and inspire deeper introspection, even in the face of adversity. Uniquely, they had access to the so-called library ‘Special Storage’ (spetzkhran) reserved for the members of Soviet scientific/academic community. Their intellectual milieu, epitomized by figures like Monastyrsky and Kabakov, was exceptionally assertive and successful in obtaining “restricted” reading material and various Western resources. (Zdenek 2000).

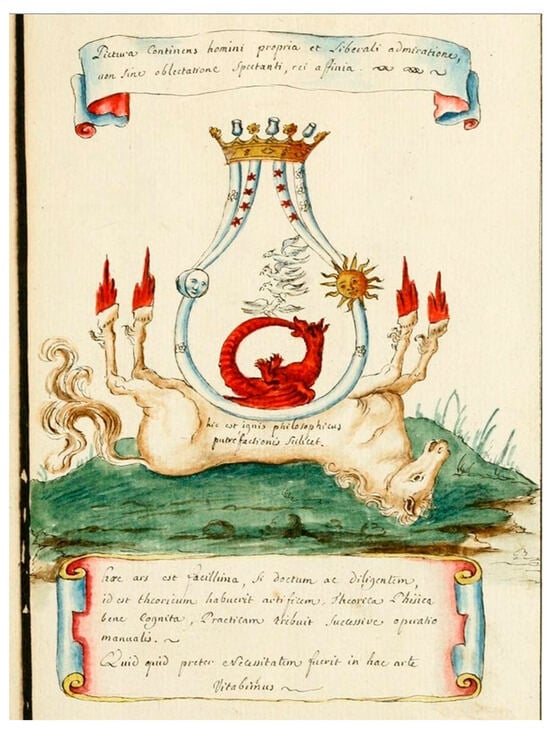

For the purposes of this essay, I consider the potential influence of Moscow Conceptualism stemming from the broader historical context of mushroom symbolism and esotericism. This encompasses various cultic depictions of mushrooms, particularly the fly agaric, along with the topical spiritual dimensions associated with them. Throughout its existence, Moscow Conceptualism has been marked by a playful engagement with metaphysical themes, often expressing sarcasm and irony directed at various targets, a characteristic trait often referred to as ‘Russian steb’ (Ioffe and Oushakine 2013; further elaborated upon below). This essay illustrates how mushrooms, long revered in ancient religious and magical traditions, continue to hold significance as catalysts for various provocative cultural endeavors within the artistic collective consciousness. Fungi play pivotal roles in subversive cultural movements, artistic expressions, and common practices. This paper delves into a remarkable case study of a neo/post/avant-garde practice, which, through the lens of ethnomycology, can aptly be characterized as a ‘blurred genre’, if to borrow from the theoretical framework proposed by Clifford Geertz. Another objective of this essay is to highlight the potential reference (and relevance) to the alchemical imagery within Russian Conceptualism, focusing on the unique process of fluid transmutation where one entity transforms into another. This phenomenon underscores the birth of novel entities through the mutation of existing concepts and representations, revealing intriguing layers of meaning within the movement. (Glanc 2001; Kusovac 2019).

By and large, this article zooms in on the iconographic origins of mushroom imagery within the Moscow Conceptualist milieu, highlighting the potentially infinite depth of knowledge they represent. The focus lies on exploring the potential influence of esoteric mushroom symbolism within the conceptualist community. It is more appropriate to refrain from passing judgment on the historic empirical accuracy of specific beliefs regarding mushrooms’ nature, their anthropomorphic interpretations, or notions concerning the figure of Christ. The ad hoc goal is not to privilege any specific notion but to try to describe their potent existence as well as their relevance to the provocative iconography characteristic of Moscow Conceptualist circles. Mushrooms occupy a very special niche in the early-modernist cultural milieu. One may refer to the Belgian Symbolist Charles Van Lerberghe’s famous Sélection surnaturelle, conceived in 1905, known also under the title of ‘Les Aventures merveilleuses du Prince de Cynthie et de son serviteur Saturne’ which develops the science-fiction notion of huge blue fungi which upon consummation magically transport those who ate them to the distant centuries, allowing them to dwell in a hallucinogenic reality of the newly transformed universe.

Central to this exploration of fungal psychotropic reality arises the controversial figure of John Allegro, whose work on the sensual occult nature of a Christ figure involving mushrooms de facto lacks scientific acceptance and verifiable credibility. It belongs rather to the New Age occult metaphysics than to the domain of normal science. Nevertheless, these concepts hold significant sway in the realm of history of (esoteric) ideas, contributing to the surrealistic alchemical essence inherent in conceptualist art. Moscow Conceptualism has long been intertwined with the legacy of surrealist culture, and Allegro’s provocative exploration of psychedelic Occultism, as discussed below, aligns seamlessly with this tradition.

To grasp the iconographic foundation of mushroom-themed surrealism within Moscow Conceptualism, as exemplified by artists like Kabakov, Makarevich–Elagina, and the group ‘Mukhomor’, it is essential to delve into reflections on esoteric and erotic Occultism, mushroom-suggestive gnostic alchemy that evokes fungal associations, and related subjects. Primarily, it is essential to define our interpretation of New Age esotericism, a category under which we position Moscow Conceptualism in this broad context. The primary object of the study of this essay is therefore the visual artistic creation of Moscow Conceptualism, while the secondary, auxiliary matter of enquiry is the esoteric universe of the New Age occult and the related minor currents that are discussed as the source of influence and potential gravity.

What actually represents Moscow Conceptualism as such? This highly elusive art movement showcases a conglomerate of various artistic groupings that gradually emerged in Moscow in the late 1960s, continuing though the 1980s and has had a significant impact on Russian art and culture in general (Rosenfeld 2011; Nicholas 2024). It is associated with a wide range of art forms, including painting, sculpture, photography, video, and especially installation and performance art (Nicholas 2024; Ioffe 2016, 2017). The main ideology of Moscow Conceptualism presumes that a work of art should not only represent a skillfully created aesthetic object, but more importantly, it must pose the original idea or concept that underlies its entire ‘mental’ being of thought. In this sense, conceptual artists tend to prioritize the originality of wording or the spiritually visionary nature of the conceptual ideas and messages they are usually trying to convey through their complicated activities. One of the key aspects of Moscow Conceptualism is its carnivalesque-critical attitude towards Soviet reality and official ideologies of all kinds. Artists of this current actively and provocatively explored themes of political censorship, identity, history, and social reality, expressing their subversive thoughts and ideas through abstract creations and symbolic art forms. The movement, among other things, openly championed esoteric and mystic subtexts in their aesthetic programs. The originality of Moscow Conceptualism for art history lies in its combination of experimentation, sophisticated intellectualism, and a radical-critical approach to the initial cognition of reality. This movement helped to draw attention to contemporary Russian art as an essential and indispensable part of the global artistic context, spotlighting the development of international conceptual art in general (Groys 2013).

2. Introducing the Subject: Esoteric Context and the Fungi

Esotericism often emerges at the borderlines, signifying a loss of traditional culture that previously provided a rich source of metaphysical contemplation and religious action. The concept of ‘tradition’ here encompasses the broader spiritual quests of the past. Traditional knowledge about the world may cease to function normally and lose value, especially during significant events like the collapse of a large state or drastic political regime changes. Esotericism (at times also erotic), in such instances, becomes a quest for spiritual support in various alien traditions and cultures, including those rooted in foreign belief systems and practices. Moscow Conceptualism, which developed during the decadent/stagnant decline and fall of the Soviet empire, can be analogized with the emergence of Hellenistic mystery cults during the gradual decline of the Roman Empire. In this context, Moscow Conceptualism manifests as a new metaphysical mysticism, using esoteric narratives—whether visual or verbal—as stylization, bitter irony, and sometimes a peculiar form of ‘schizodiscourse’3 intertwined with a newly developed psychedelic religion (Ioffe 2020).

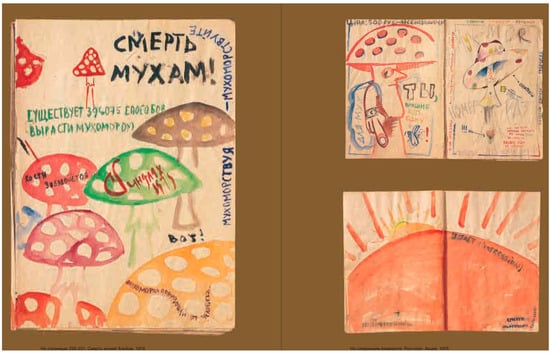

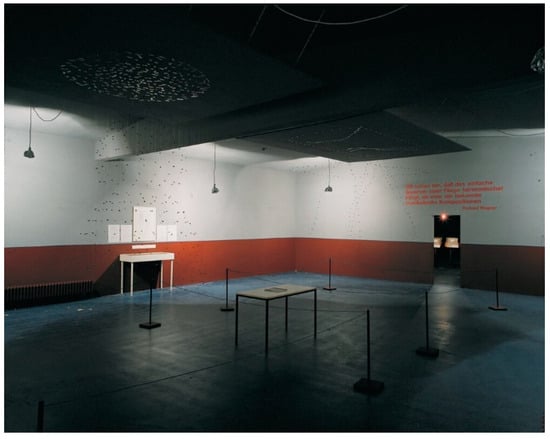

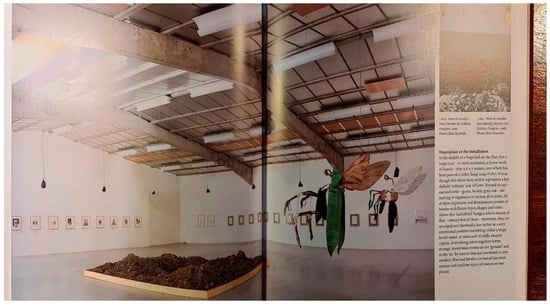

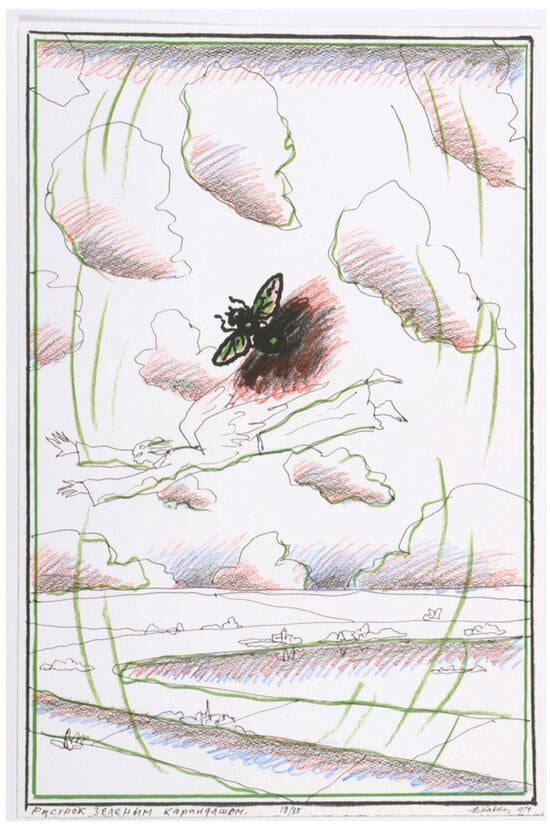

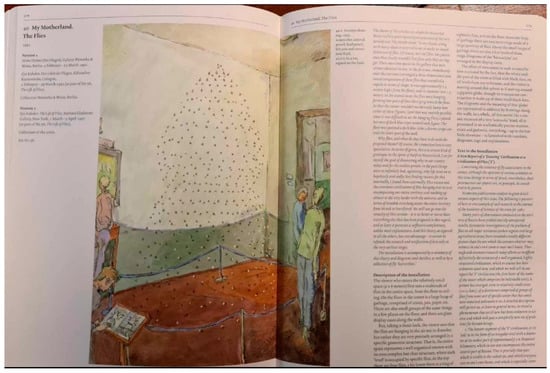

This essay aims to shed background light on the esoteric religious and quasi-religious metaphysical stiobby practices of Moscow Conceptualism, focusing on the roots of its ‘mushroom artistic system of thought’ with the groups like Mukhomor, Collective Actions, and Medgermeneutika. It analyzes the origins of this unique psycho-hallucinatory (post-)religion, providing concrete examples of myco-centric esoteric Buddhism as applied to Russian soil by figures like Andrei Monastyrsky in their art performances, diaries, and personal behavior (Ioffe 2013, 2016). The paradigmatic paternal figure of Ilya Kabakov emerges by the end of the essay in relation to the infernal insects that correspond to the fly-agaric theme of the discussed artistic esotericism (on general imagery of mukhomor, see Ioffe 2020; Batyanova 2001a, 2001b).

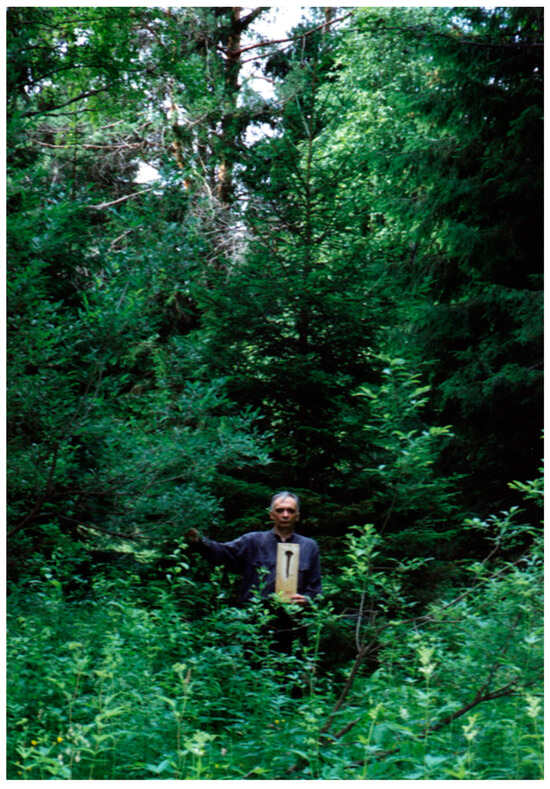

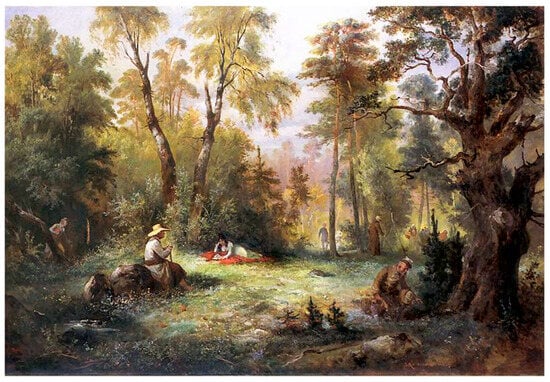

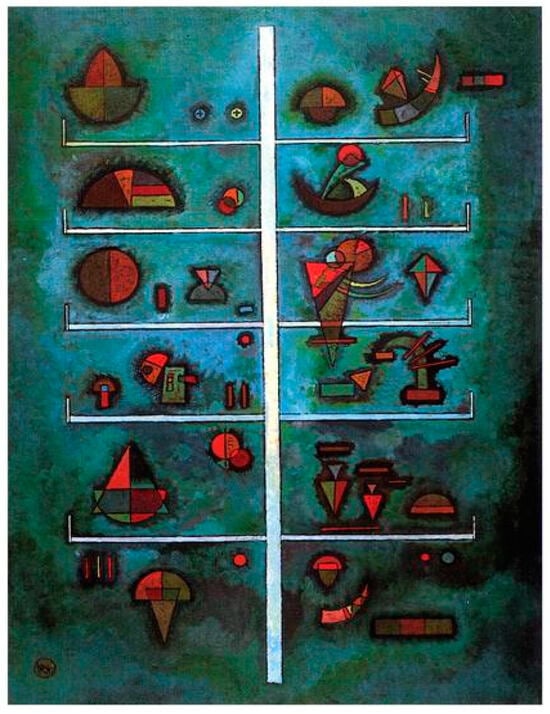

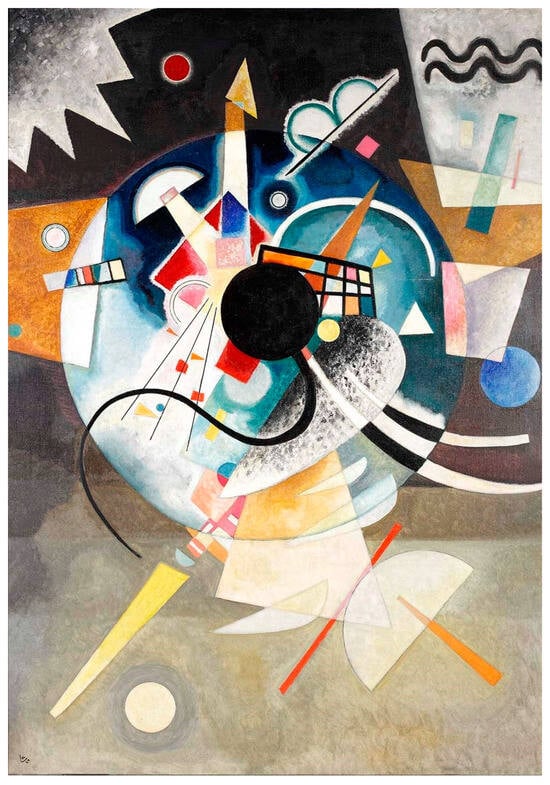

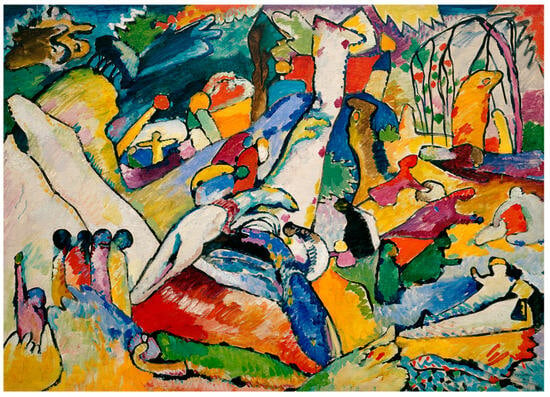

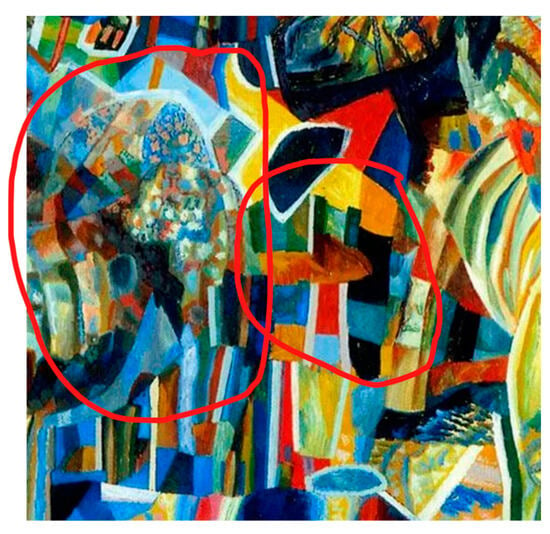

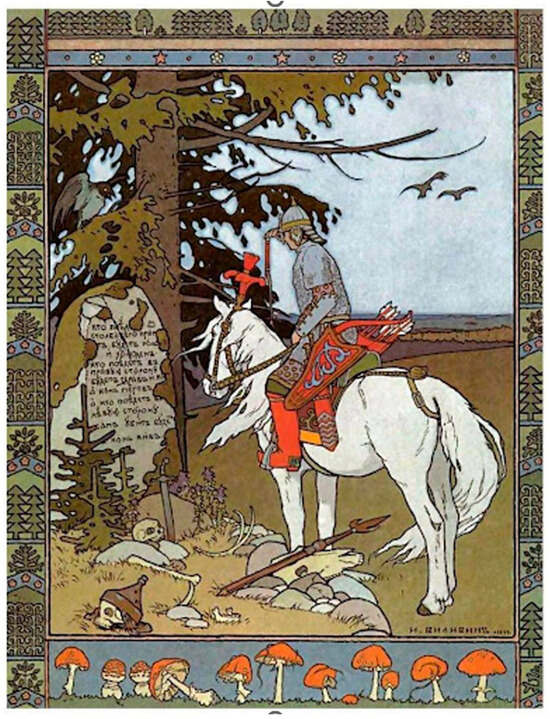

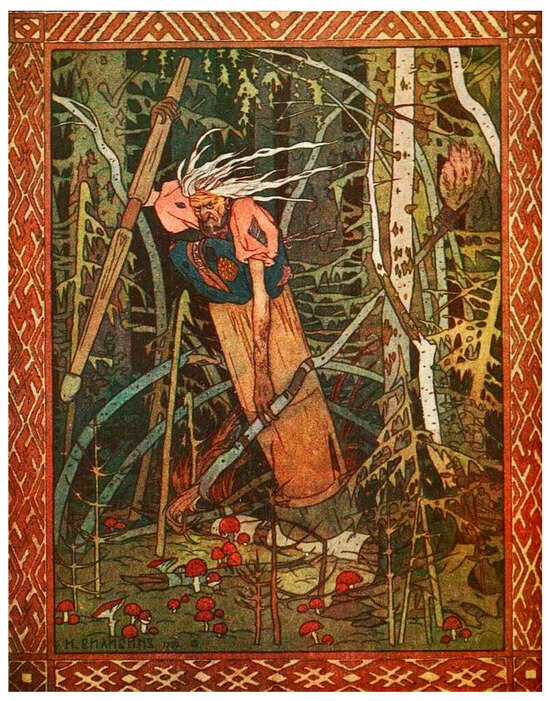

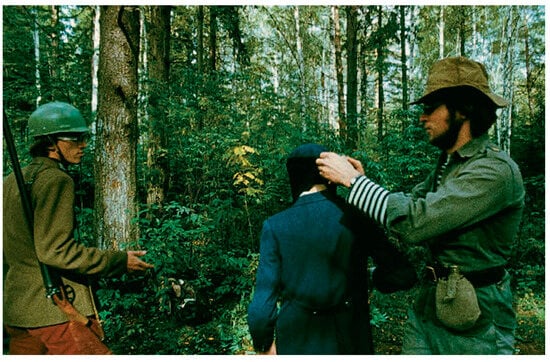

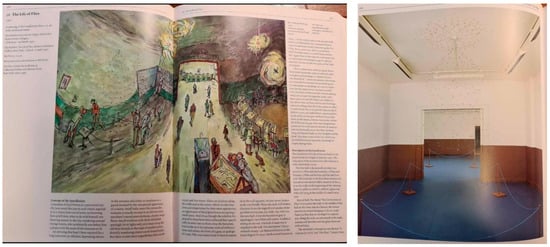

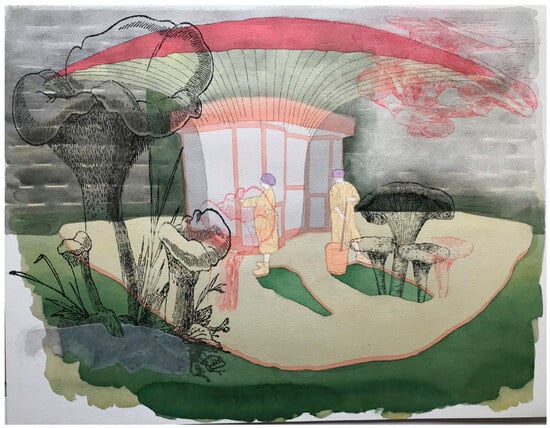

Here (Figure 1), Monastyrsky is possibly parodying the famous picture by Wassily Kandinsky with a rider that ‘escapes’ his destiny as it gradually dissolves within the green impressionistic landscape.

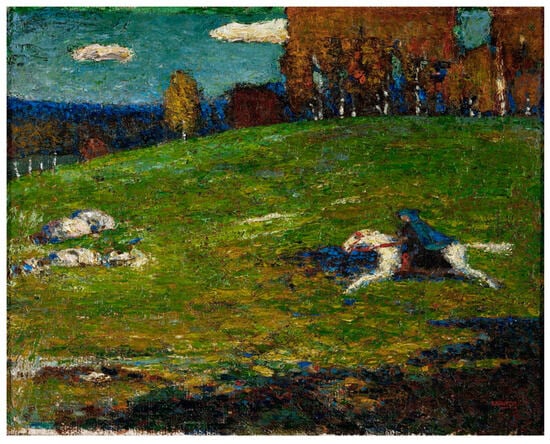

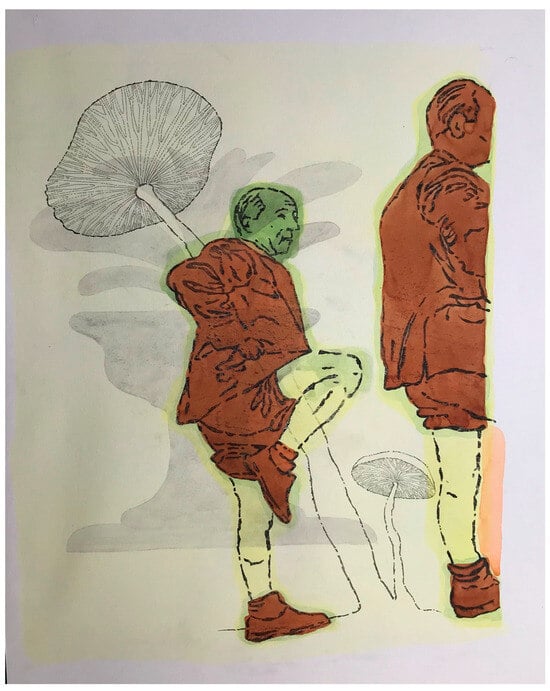

Instead of Kandinsky’s modernist velocity, Monastyrsky showcases the static (or even the stasis) and instead of a horse—a mushroom, or rather a painted conceptual image of it, referring to the semiotics of Joseph Kosuth’s masterwork “One and Three Chairs” (created in 1965). Monastyrsky’s virtual (or alchemical) connection to the mushroom is established through his exploration of the symbolic significance within an image and its resonance with the stillness inherent in this visual performance. By equating the depth of meaning found in both perceptual representation and static expression, he deepens his suggested identification with the mushroom, finding common ground between its essence and his own artistic expression. This alignment underscores his belief in the power of hidden symbolism and the transformative potential of art to convey profound insights about existence and human experience. The Blue Rider offers a notable contrast (Figure 2): which in its own turn compositionally somewhat reminds one of Georges Seurat’s canvas “Farmer Work” 1883 (Figure 3), bearing a suggestive allusion to the process of a natural mushroom selection and picking:

The evocative imagery of suggestive mushrooms can be found in the creative oeuvre of several prominent artists of Russian and global Modernism and the avant-garde. The intricate interrelation between the Russian historical avant-garde and Moscow Conceptualism is deeply embedded in both movements’ profound engagement with radical and innovative artistic expressions, albeit emerging from disparate historical contexts and pursuing distinct objectives. Both movements’ profound dedication to innovation and experimentation was epitomized by an emphatic departure from traditional art forms and a fervent quest for novel artistic languages. The avant-garde, analogous to Conceptualism, endeavored to amalgamate art with quotidian existence, significantly impacting architecture, design, and propaganda. Moscow Conceptualists articulated a defiant response to the state-mandated doctrine of Soviet ideo-realist approaches, striving to engender art that was reflective, critical, and frequently imbued with irony, accentuating the primacy of the concept or idea underpinning the artwork over its aesthetic attributes.

A salient characteristic of many conceptualist works is the coherent artistic integration of text and language, which serves as a medium to critique the power structures and constraints imposed by Soviet ideology. The employment of diverse working media, including performance art and installations, by these movements, sought to subvert and redefine traditional conceptions of art. The avant-garde movements instigated a rupture from 19th-century rigid realism and mainstream academic art (Ioffe and White 2012), while Moscow Conceptualists repudiated Socialist Realism as the best and the most characteristic instance of the “sanctioned art form”. Each movement operated within a highly politicized milieu: the avant-garde initially aligned itself with the revolutionary zeal of the nascent Soviet state, whereas Moscow Conceptualism emerged as a critique of the stagnation and autocracy of the late Soviet era. The philosophical foundations of both movements were profoundly influenced by contemporary philosophical and theoretical discourses. The avant-garde, nourished by the tenets of Futurism, Constructivism, and Suprematism, generally served as a progenitor to Moscow Conceptualism, which also drew inspiration from Western conceptual art as well as the sophisticated traditions of semiotics and structuralism. Both movements espoused the ethos of ‘Art as Life’ praxis: the avant-garde’s aspiration to fuse art with everyday life found a meaningful resonance in Moscow Conceptualism’s employment of mundane objects and vernacular language to articulate profound insights about reality and society. The historical avant-garde established a foundation that enabled subsequent generations to challenge prevailing artistic and societal norms. In many respects, Moscow Conceptualists revitalized the spirit of radical experimentation that the avant-garde had initially inaugurated, albeit in a context necessitating subtlety and irony to circumvent censorship and potential political repression. Avant-garde was renowned for its audacious utilization of novel materials and techniques in painting, sculpture, and architecture. In contrast, Moscow Conceptualists frequently resorted to “traditional” text, semi-theatrical series of quasi-spontaneous performance, and the new art form to be known as ‘installations’ to convey their complex messages, often engaging in a metacritique of Soviet society and its concealed hypocritical politics. Despite the temporal and political disparities separating the Russian historical avant-garde and Moscow Conceptualism, both movements were united by a steadfast commitment to challenging the status quo and exploring new artistic possibilities to the widest possible extent. Moscow Conceptualism can thus be perceived and then construed as a continuation and reinterpretation of the avant-garde’s radical legacy, meticulously adapted to the specific exigencies of the late Soviet period. As I have pronounced a number of times in my previous publications—avant-garde and avant-gardists gave technical as well as spiritual birth to conceptualism and conceptualists (Ioffe 2013, 2016).

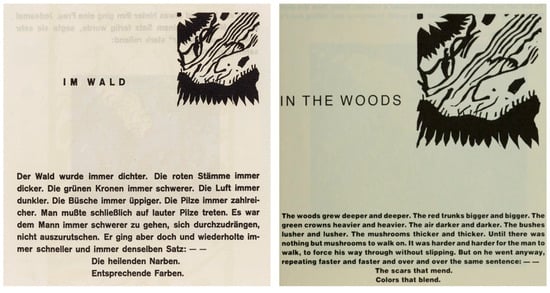

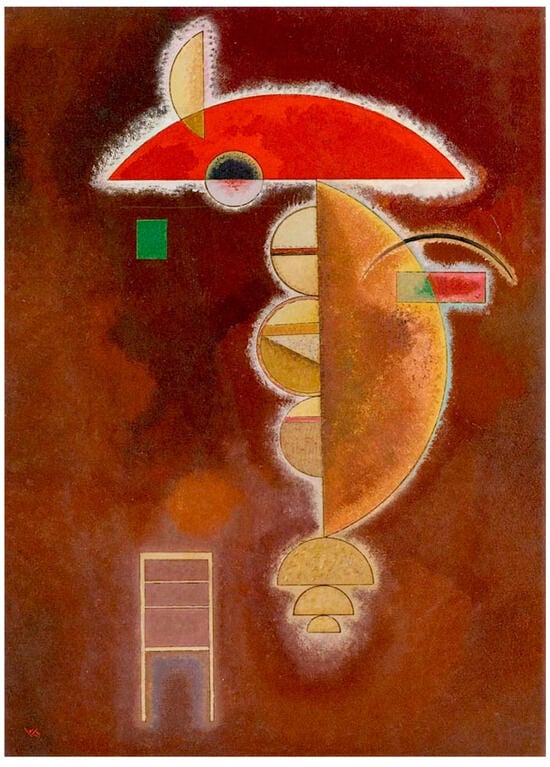

Foremost among these avant-gardists appears Wassily Kandinsky, whose shamanistic mushrooms have garnered considerable recognition.4 In Wassily Kandinsky’s multidimensional oeuvre, the recurring presence of mushrooms serves as a multifaceted symbol, embodying both tangible and metaphysical elements within his artistic expression. As a pioneering figure in abstract art, Kandinsky employed mushrooms as visual motifs to convey complex themes related to nature, spirituality, and the subconscious mind. Through their organic forms and vibrant colors, mushrooms in Kandinsky’s compositions often evoke a sense of extraordinary vitality and even some sort of theistic mysticism, inviting viewers to discern the interconnectedness of the natural world and the human psyche. Furthermore, the recurrent inclusion of mushroom-resembling objects across Kandinsky’s works (Figure 4) underscores his fascination with the transformative potential of art, wherein mundane subjects transcend their physicality to become conduits for transcendental experiences. Thus, the remarkable role of mushrooms in Kandinsky’s visuality extends beyond mere representation, serving as symbolic portals to realms of imagination and intangible illumination. In Kandinsky’s renowned poetic volume “Klange” (Sounds) (Kandinsky 1981) comprising prose poems and engravings (appeared in 1913 in the pre-war Munich), magical mushrooms feature within an esoteric framework intertwined with ancient pagan beliefs corresponding to a Thunderer deity (see the discussion below on Vladimir Toporov’s phallic mushroom symbolism).

The [magic] forest grew thicker and thicker. The red trunks turned increasingly dense. The green foliage became much heavier. The air grew darker. The bushes grew lusher. The mushrooms appeared to be more abundant. Eventually it was necessary to walk right through the mushrooms. It was increasingly difficult for a person to walk, treading rather than slipping.

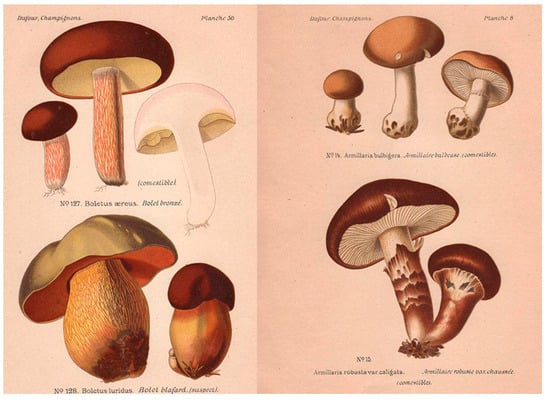

At the time of Kandinsky, the exploration and utilization of mushrooms were already subjects of extensive study and fascination. Scholars and enthusiasts alike delved into the diverse array of mushrooms, probing their culinary, medicinal, and cultural significance. From ancient times to Kandinsky’s era, mushrooms held a multifaceted allure that transcended mere sustenance, embodying some mystery, hidden folk symbolism, and also scientific intrigue. In Kandinsky’s milieu, the realm of mycology had been enriched by years of observation and experimentation. Ethnobotanists documented the traditional uses of mushrooms by different cultures, revealing a tapestry of practices ranging from culinary delicacies to spiritual sacraments. Meanwhile, scientists scrutinized the biochemical composition of mushrooms, uncovering potential therapeutic properties and unlocking new avenues for pharmaceutical research.

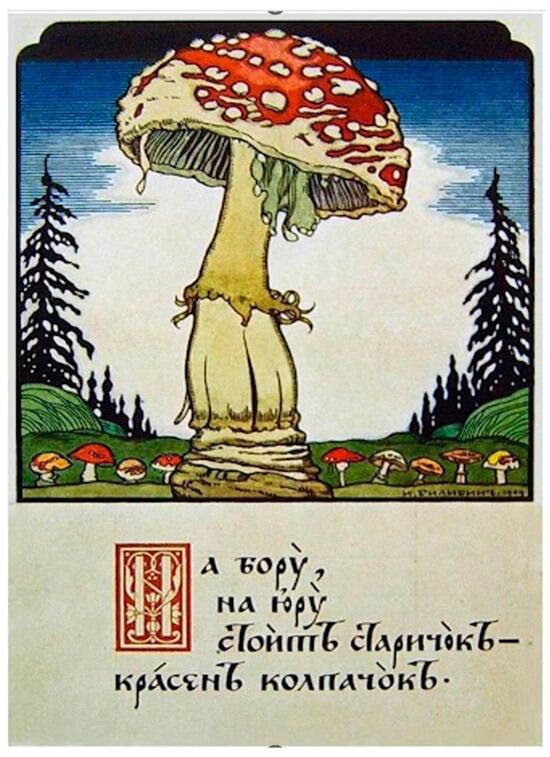

Kandinsky himself may have been drawn to mushrooms not only for their practical appeal but also for their aesthetic and symbolic resonance. Just as he explored the expressive potential of colors and shapes in his art, mushrooms offered him a rich metaphorical vocabulary. Their ephemeral beauty, nestled between decay and regeneration, echoed themes of transience and transformation that permeated his work. Furthermore, the burgeoning interest in mycology intersected with broader cultural movements of the time. The fascination with nature, fueled by Romanticism and later by the burgeoning environmental consciousness, spurred renewed interest in the study of fungi. Intellectual representatives of the new historical age found in mushrooms a potent symbol of the interconnectedness of all living things, inspiring new perspectives on humanity’s place in the natural world. In this context, Kandinsky’s artistic exploration of mushrooms would have been both timely and resonant. Whether as subjects of ethnographic research or as motifs in abstract compositions, mushrooms provided him with a rich visual vocabulary to explore themes of nature, spirituality, and the subconscious. Thus, while Kandinsky’s era may not have been defined specifically by a mushroom craze, the fascination with fungi was undoubtedly a vibrant thread in the cultural tapestry of the new “eco-time”, weaving its way through art, ethnography, and philosophy with a richness that mirrored the diversity of the mushrooms themselves (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Leon Dufour. Atlas des Champignons Comestibles et Veneneux. 1891. “Of mushrooms there were plenty: the lads gathered the fair-cheeked fox-mushrooms, so famous in the Lithuanian songs as the emblem of maidenhood, for the worms do not eat them, and, marvelous to say, no insect alights on them; the young ladies hunted for the slender pine-lover, which the song calls the colonel of the mushrooms, All were eager for the orange-agaric; this, though of more modest stature and less famous in song, is still the most delicious, whether fresh or salted, whether in autumn or in winter. But the Seneschal gathered the toadstool fly-bane”. ‘Pan Tadeusz’ by Adam Mickiewicz ([1834] 1917).

In the corpus of traditional Slavic lore, many esoteric attitudes, intrinsically intertwined with the tenets of Christianity, were employed to guarantee an abundant mycological harvest. It was believed that the inaugural gaze upon the forest during the beginning of the day of Christmas would predestine a prolific bounty of fungi during the festival season. Furthermore, during the solemn Sunday Matins of Pascha, upon the sacerdotal proclamation ‘Christ is risen!’, the appropriate response would be, ‘I desire to gather mushrooms’. This invocation aligns the act of mushroom gathering with the sanctified Name of Jesus Christ, casting an intriguing Slavic nuance upon John Allegro’s contentious hypothesis. Paradoxically, it was deemed anathema to enact the signum crucis or to engage in prayerful supplications whilst embarking on a fungous foray, for mushrooms were perceived as sentient entities; they would ostensibly discern the sacred utterances and promptly sequester themselves subterraneously. Conversely, upon ingress into the sylvan expanse, it was customary to procure three arboreal branches from disparate species and place them within one’s headgear. Subsequently, the initial triad of mushrooms discovered were to be reverently deposited into a tree’s hollow, accompanied by the thrice-recited Pater Noster. The spiritual rites extended further, wherein the primordial mushroom harvested was to be ceremoniously baptized and affectionately kissed upon its cap, thus imbuing the entire enterprise with a profound ecclesiastical gravitas (see the context in Belova 1995).

The potential impact of the pan-Slavic element of the mushroom-religion or peculiar mushroom-obsession is yet to be discovered. At this point, we can commonly observe the unique importance of fungi in, among others, the Polish context. The best-known Polish national Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz, in his principal work ‘Pan Tadeusz’ (1834), mentions the process of passionately gathering the wild mushrooms. Stanislaw Trembecki, a prominent literary figure of the late 18th-century Polish classicist period, left several interesting ruminations on that matter. During the 17th century, the esteemed Polish baroque poet Waclaw Potocki in his work ‘The Unweeded Garden’ discussed wild mushrooms extensively, suggesting that mushroom hunting is an arcane practice best left to those with specialized knowledge. This attitude hints at the pan-Slavic, so to say, cultural obsession with mushrooms and their various forms of living and consuming.

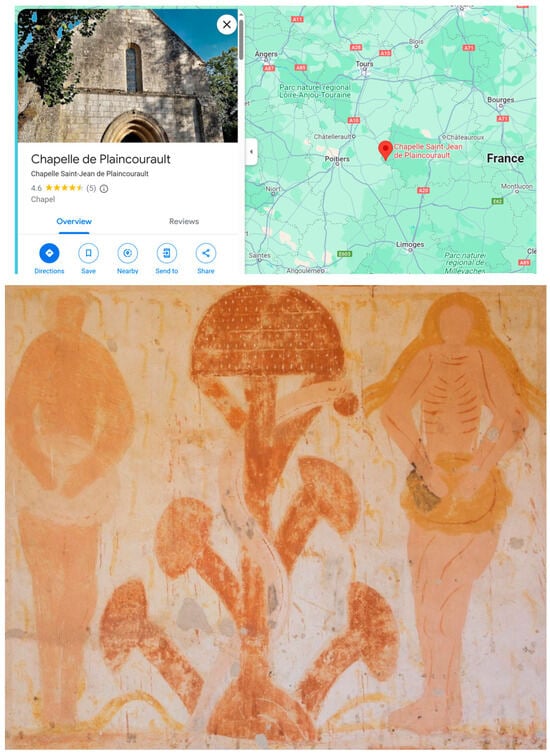

Polish mythological conceptions and representations concerning the genesis of mushrooms (Figure 7) exhibit a remarkable congruence with those held by Ukrainians and Belarusians. These beliefs frequently intertwine with apocryphal narratives detailing the terrestrial sojourns of Christ and the apostles. One such esoteric legend posits that mushrooms originated from the expectoration of the Apostle Peter, who, while clandestinely consuming bread, choked upon being suddenly questioned by Christ, causing him to expel the crumbs, which subsequently somehow metamorphosed into mushrooms. Polish folklore further contends that certain fungi were once mythical human gnomes transmuted through divine intervention, and that the late autumnal rappu mushrooms are, in deeper reality, nothing but bewitched sorceresses. Moreover, mythological entities possess the capability to transform humans into all sorts of flora, including mushrooms. An illustrative example is found in a certain East-Slavic fairy tale wherein a devil transmutes a comely princess into a birch tree. In another Ukrainian legend, a mermaid entices a handsome youth named Vasil into a meadow on Trinity Day, where she erotically tickles (schekochet) him to death with her feminine tickler (schekotun = clitoris), eventually mercilessly transforming him into a cornflower (basil). These myths underscore a profound belief in the intrinsic connection between humans and the vegetal realm of spores, attributing anthropomorphic qualities to all living entities. Plants were perceived as sentient beings endowed with souls. In Polish, the term ‘dusza’ (soul) also signifies the essence of the vegetal trunk. Within the mythological cosmos, plants were envisioned as animate entities capable of locomotion, communication through the susurrus of leaves, and the generation of sounds via their branches or foliage. Mushrooms, in particular, were considered to be sentient organisms possessing their own secret language, and it was believed that one could theoretically try to discern the semiotics of their squeaks within the forest (See Usacheva 2000; Munn 1973).

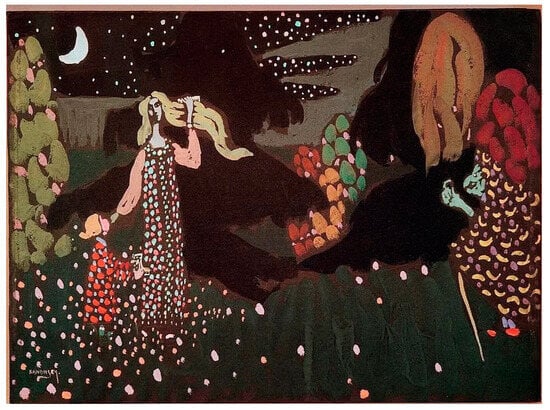

In fact, a unique cultural relevance of magic mushrooms in Russia is prominently displayed throughout numerous artworks created by Wassily Kandinsky. One of these is “The Night” (1907) (Figure 8) is replete with various suggestive colorful spots that evidently resemble forest fungi. Both of its main characters—Mother and Daughter are suggestively decorated with fungal imagery, especially the little Daughter seems to be somehow immersed in mushroom-dominated surface fabric. Aside from the wicked magician on the right, Mother (center-left) appears to be feeding her child with a handful of barely visible mushrooms:

Geometrized images of mushrooms are conceptually shown on the famous canvas ‘Storeys’ (1929). The conical fungi often depicted by Kandinsky manifestly resemble psilocybin mushrooms.

Apart from these, in Kandinsky’s art we encounter even more obvious representations of fungi, more evidently amanita muscaria (Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Another quite famous canvas is Un Centro (1924) (Figure 11) painted in the year of Vladimir Lenin’s timely death, referencing the end of this famous Fungus–Human leader’s rhizome-reign:

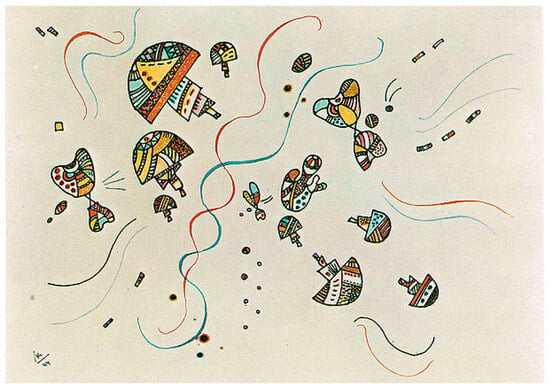

The very final painting of the artist’s entire career is the so-called Last Watercolor, (Figure 12) created at the year of Kandinsky’s death (1944).

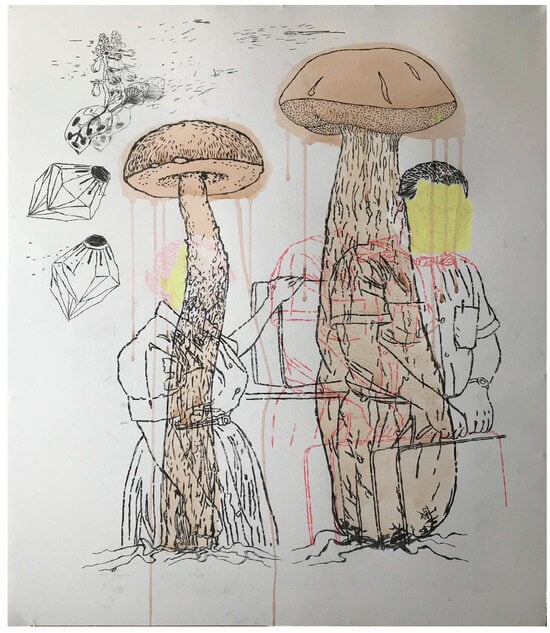

Aside from these artworks, we must also mention a rather overlooked earlier canvas titled ‘Sketch for ‘Composition II’ (Skizze für “Komposition II’) (Figure 13) created as early as 1909 (or 1910). One may find there some evident mushroom-related imagery, in particular delving into the anthropomorphic fusion between human bodies and the fungus. Several human figures there are portrayed as fungi with characteristic heads and corresponding body lines.

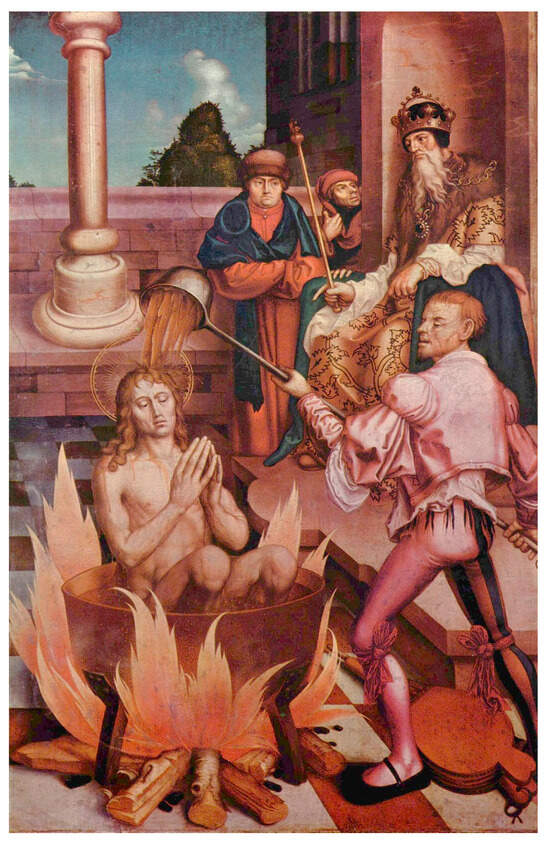

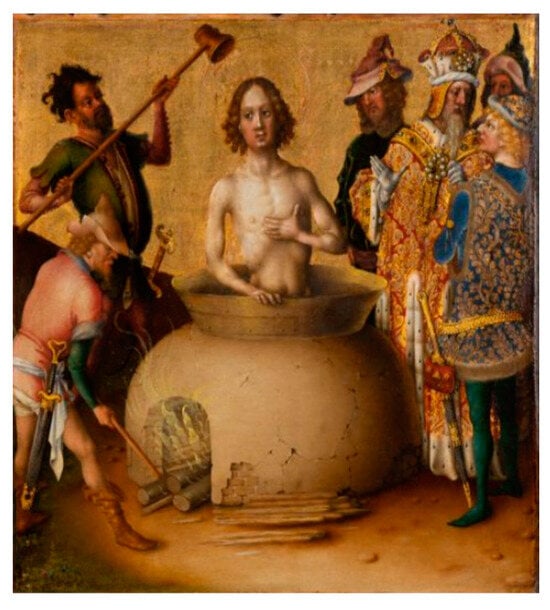

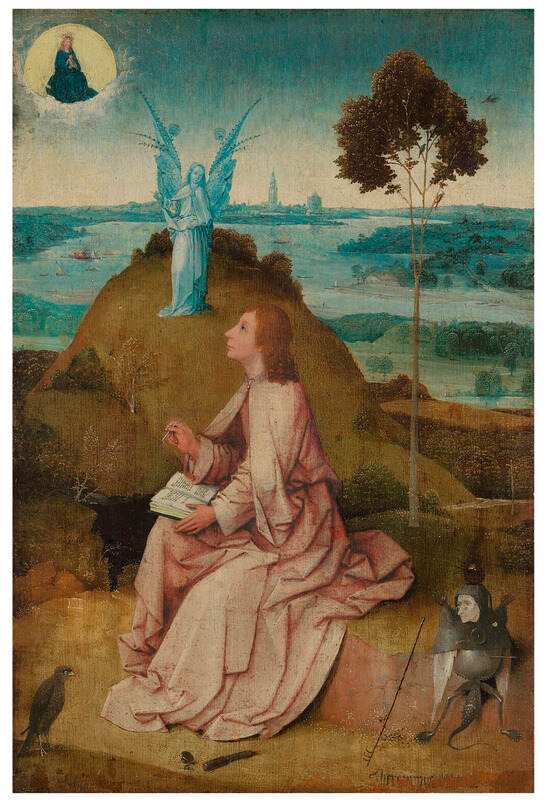

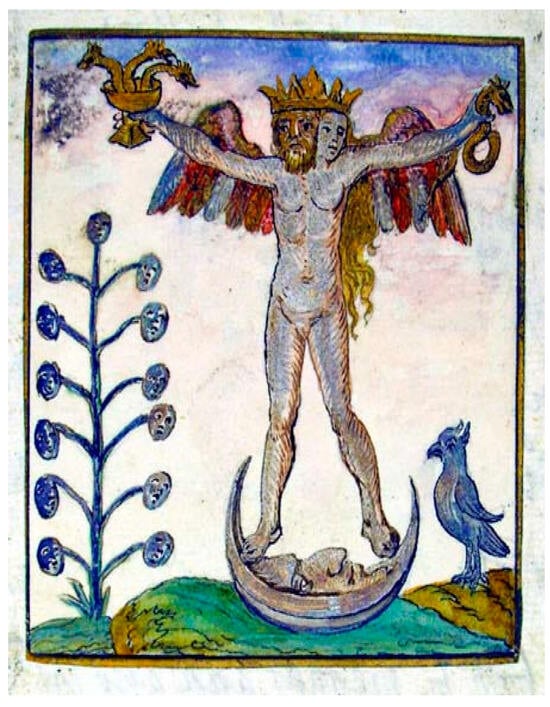

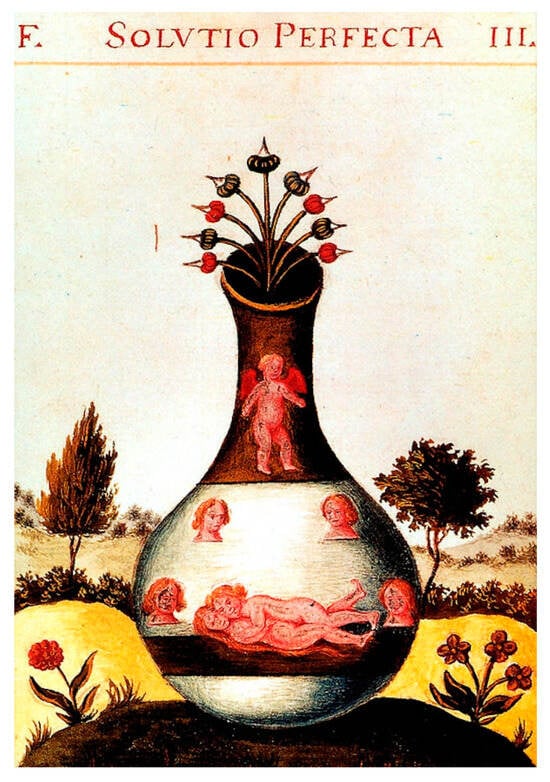

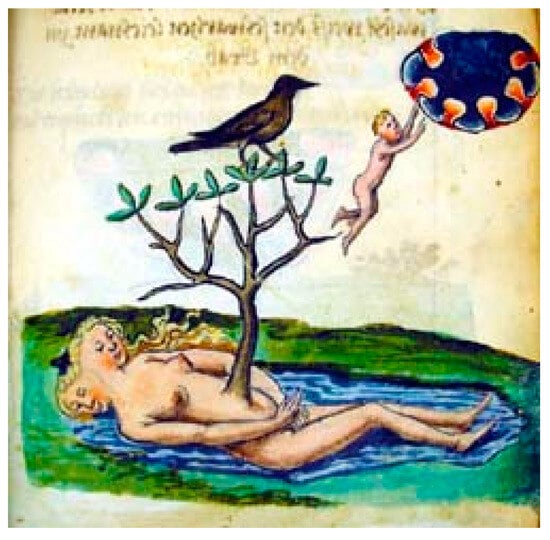

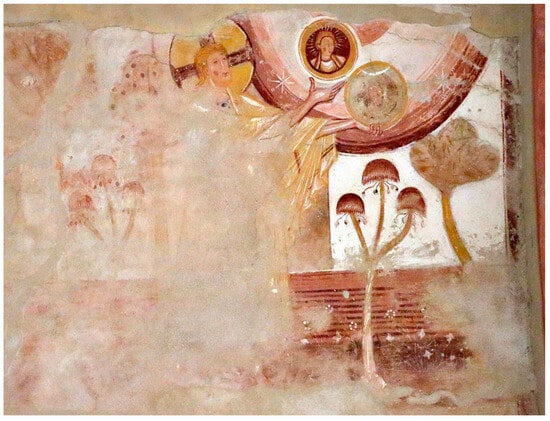

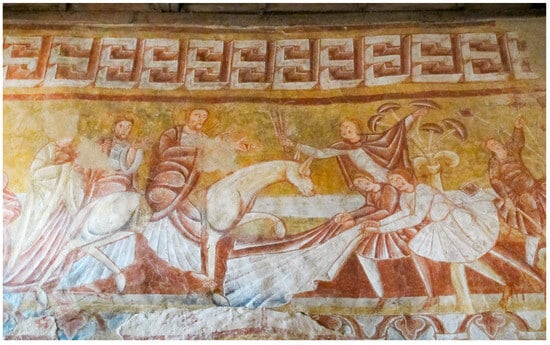

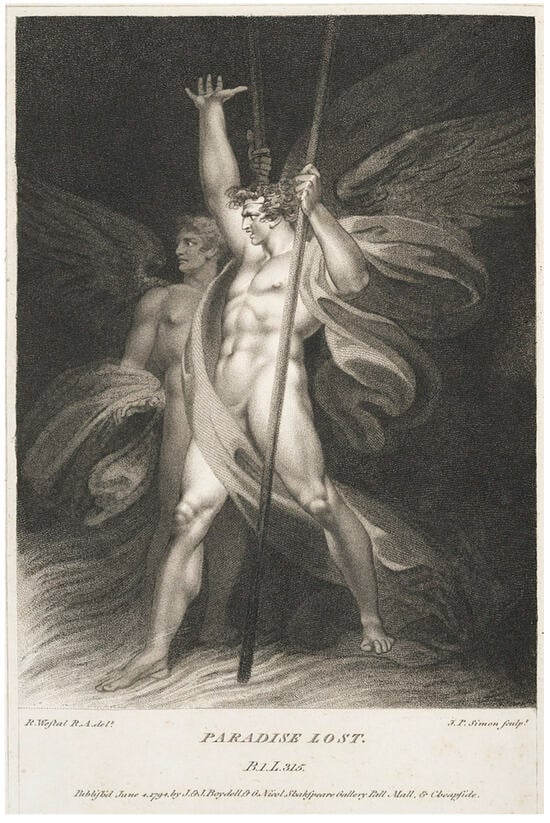

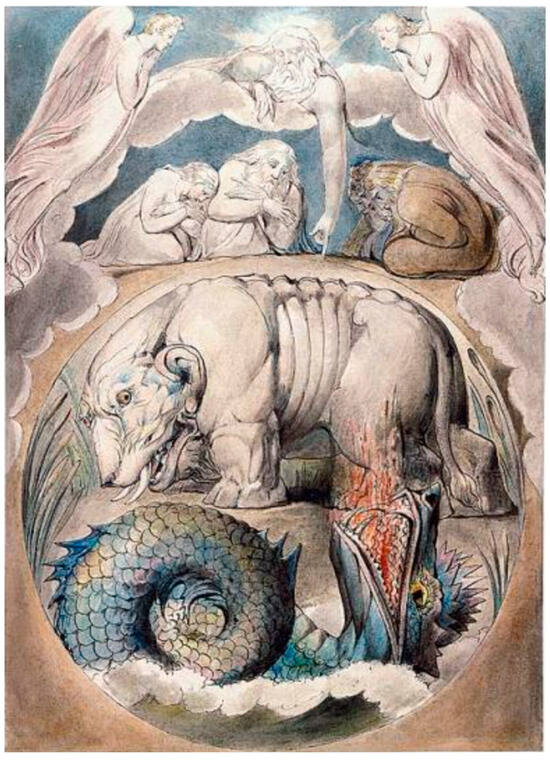

This painting, approaching the rather significant year of 1910, reflects Kandinsky’s deep engagement with the complex of theological and spiritual contexts related to the apocalyptic Book of Revelation of Saint John (Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16).5 Some canonical images of St John bear interesting allusions to the theme of alchemical transformation and myco-homunculus transmutation6:

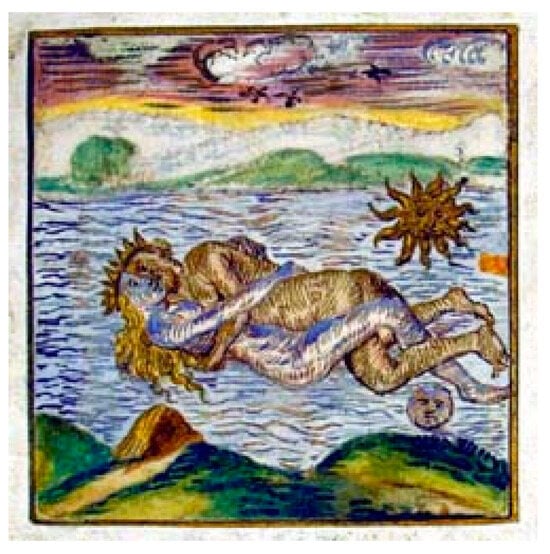

In Kandinsky’s apocalyptic vision, Nature is depicted through the enduring, syncretic image of a Divine Rider, symbolizing one of the Horsemen of the Apocalypse, destined to bring epic destruction to the world as we know it. This abstract portrayal of cataclysmic events is ultimately a pathway to spiritual salvation, as envisioned by Kandinsky. The artwork hints at various natural disasters, such as a future global deluge, and features suggestive figures like serpents and fungi-people, who come together in a new cosmic alliance. Kandinsky’s use of vivid colors and dynamic forms intensifies the sense of impending chaos and imminent material transformation. He appears to implicitly be quoting the famous apocalyptic assertion of Apostle Paul that ‘we will not all sleep [in death], but we will all be [completely] changed [wondrously transformed]’ (1 Corinthians 15:51). The swirling patterns and fragmented shapes evoke a world in turmoil, where established biological orders are dissolving, making way for a new spiritual awakening. Kandinsky’s Divine Rider, a central figure in this apocalyptic vision, not only embodies destruction but also heralds a profound natural renewal. This duality of destruction and creation is a recurring theme in Kandinsky’s oeuvre, emphasizing the cyclical nature of existence and the possibility of rebirth through upheaval. Moreover, the painting reflects Kandinsky’s specific approach to his developing art of radical abstraction, gradually moving away from traditional mimetic representation to convey profound spiritual truths revealed to the initiated few. By abstracting the elements of nature and myth, he gently invites viewers to interpret the imagery on a personal, intuitive level, engaging with the universal religious themes of destruction, salvation, and renewal. The serpents and fungi-people, as symbolic figures, suggest a perpetual symbolic metamorphosis, hinting at the interconnectedness of all life forms and the potential for collective transformation. In essence, this painting is not just a reflection of a major apocalyptic prophecy but also a visionary statement on the transformative power of art that conveys new modernist spirituality. It challenges viewers to look beyond the immediate chaos and destruction, to envision a future where spiritual salvation emerges from the depths of cosmic upheaval. As I have mentioned above, Kandinsky’s life-long profound fascination with the mushroom universal imagery may be directly linked to his early interest in shamanism and the related professional anthropological quests (Weiss 1995). Mushrooms, with their bridge-transformative essences, mysterious and almost magical qualities, symbolized a boundary between the materiality of the physical dimensions contrasted with the spiritual worlds. This aligns very well with Kandinsky’s initial quest to explore and delineate the eternal-spiritual in art, transcending mere representation.

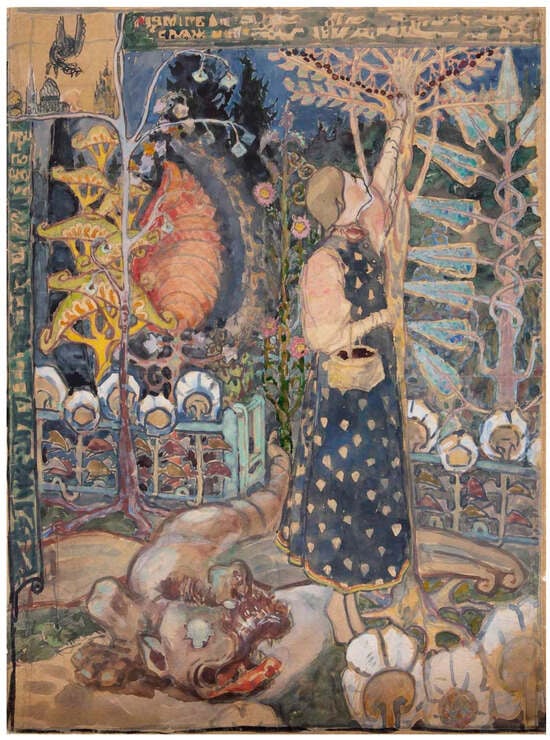

Within the very same context of the suggestive use of fungal imagery in Russian pictorial avant-garde, we should also mention the somewhat less well-known concealed mushrooms of an eminent Russian avant-garde painter Pavel Filonov (Figure 17 and Figure 18):

There seems to be amorphous fungal imagery, possibly of a hallucinogenic nature, integrated in this canvas (resembling to Slavic “poganki”):

Filonov, along with Kandinsky, always remained among the favorite paradigmatic painters very well respected by the Russian Conceptualist milieus. It is considerably simpler to discern the underlying visual foundations (at times erotic) that spurred mycological interest stemming out from Russian Conceptualism, as they are firmly rooted in the shared lineage of Modernism and the avant-garde movements. Delving into this matter reveals a rich tapestry of influences and inspirations that shaped the aesthetic inclinations of Russian Conceptualists towards mycology. (Ioffe 2008a). These influences stem from the avant-garde’s embrace of radical mental and visual experimentation, the rejection of traditional artistic norms, and the exploration of unconventional mediums and subject matters. Furthermore, the symbiotic relationship between modernist principles and the avant-garde ethos provided a fertile ground for the emergence of mycological themes within Russian Conceptualism. Through a truly thorough examination of historical contexts, artistic manifestos, and visual analyses, one can try to unravel the intricate connections between mycology and the broader artistic discourse of Russian Conceptualism. This exploration not only sheds light on the visual allure of fungi within the movement but also underscores the profound impact of avant-garde ideologies on shaping artistic sensibilities in Russia during the post-avant-garde Conceptualist era.

One may consider elucidating a salient characteristic of Slavic, particularly Russian, onomastics, manifesting an intrinsic cultural and linguistic phenomenon. It is within the purview of Slavic languages, notably Russian, that surnames such as ‘Grib’ and ‘Gribov’ are quite frequently prevalent. Possibly the Russian name “Gubin” or Ukrainian “Gubenko” might bear some implicit myco-allusions. In the Polish context one may remember the family name of Grzybowski. These surnames are not mere linguistic curiosities but are borne by a considerable number of individuals. Contrastingly, within the Francophone world, it is not common for an individual to bear the surname ‘Champignon’7 (although Champollion was of course possible), nor would it be conceivable within the Anglophone milieu for a surname to be ‘Mushroom’. During the 25 years of living in Belgium and the Netherlands, I have never encountered someone with a surname ‘Paddenstoel’. This observation substantiates the unique and profound symbiosis between the Slavic peoples, especially Russians, and fungi, reflecting an anthropomorphization that is absent in other cultures. This cultural peculiarity offers further insight into why Russian Conceptualism, and to some extent, the antecedent avant-garde movement, often draws parallels between humans and mushrooms, encapsulating the notion of Human = Mushroom. As Olga Belova (1995) elucidates, mushrooms have historically been anthropomorphized as infernal shapeshifters or gnomes—a point that is very pertinent to be acknowledged. The pivotal concept here is the syncretism between fungi and humans, an idea that John Allegro also expounded upon in the context of Christ (see the details below). This onomastic suggestive phenomenon underscores a deeper, almost metaphysical intertwining of identity, where the nomenclature reflects a cultural reverence and symbolic amalgamation of human and mushroom. This confluence is not merely lexical but indicative of a broader ontological perspective within the Slavic ethos, wherein the mushroom is emblematic of certain anthropological and existential attributes, further enriching the tapestry of Slavic linguistic and cultural identity.

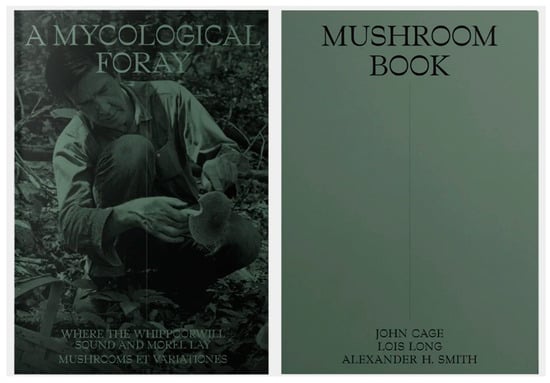

This exploration extends to the artistic interpretation of fungal cults by various Conceptualist art groups, affecting literary texts, visual materials, and performance practices. Central to the discussion is how Russian Conceptualists utilized the Eurasian tradition of mukhomor consumption both inwardly (through ingestion) and outwardly (in the creation of various art objects). The exceptional fungal cult they engaged in holds a direct connection with the notion of entheogens, a common element in a variety of pagan practices in the Slavic world and Eurasia, as extensively studied, among others, by Michael Harner and Mircea Eliade (Ioffe 2020). Moscow Conceptualism was generally very much dependent on the Western one, including currents like Fluxus, and in the world of music—the conceptual sounds of John Cage (See Ioffe 2016, 2022). To Andrei Monastyrsky—the informal leader of Moscow Collective Actions group—John Cage always remained an important cultural model and a constant source of influence, just like for other fellow artists of this artistic current, e.g., the late Nikita Alexeev. One should not forget that Cage could be regarded as one of the true pioneers of myco-centered international (intercontinental) cultural fashioning. Cage’s profound fascination with mushrooms blossomed during the tumultuous era of the 1930s, amidst the economic turmoil of the Great Depression, a period exacerbated by the strains of American deadly capitalism. It was during this challenging time that Cage sought solace and sustenance in the wild forests surrounding his home in the Monterey Peninsula of California. This deep connection with nature seeded the roots of his enduring passion for mycology, which burgeoned notably from the early 1950s onward. The convergence of Cage’s mycological pursuits and his avant-garde musical practice offers a compelling lens through which to examine his creative process.

His forays into the forest, often in silence, mirrored his quest for esoteric and innovative modes of thought (Cage 1972, 2020). In these solitary wanderings, Cage found inspiration not only for his mycological meditations but also for his revolutionary musical compositions. The parallels between Cage’s exploration of the natural world and his musical experimentation appear suggestively evident in his conceptual compositions. Just as he delved into the intricate networks of mycelium beneath the forest floor, Cage delved into the realm of sound, seeking unconventional methods of composition and performance. His fascination with the interconnectedness of all things, including the mycelial network, found expression in the unconventional structures and philosophical underpinnings of his music. Moreover, Cage’s engagement with mycology provided him with a unique perspective on creativity and collaboration (Nordenson 2016). The decentralized, non-hierarchical organization of fungal networks served as a metaphor for his approach to composition, which often involved chance operations and collaborative improvisation. In this way, Cage’s immersion in mycology not only enriched his artistic praxis but also offered profound insights into the nature of creativity and interconnectedness. In essence, Cage’s journey into the world of mushrooms was not merely a personal obsession but a transformative experience that deeply influenced his approach to music and creativity. Through his exploration of the natural world (Figure 19), Cage found inspiration, sound innovation, and a profound understanding of the interconnectedness of all things, themes that resonate throughout his pioneering body of work (Cage 2020).

“I have come to the conclusion that much can be learned about music by devoting oneself to the mushroom.”.—John Cage, 1954

Figure 19.

John Cage, A Mycological Foray, Mushroom Book. Los Angeles, California, Atelier Éditions, 2020.

In a broad sense, ‘entheogens’, etymologically meaning ‘generating the Divine within’, or often referred to as ‘psychoactive sacramentals’, constitute a specific class of narcotic substances with a historical usage spanning various periods and cultures (Shanon 2002; Hanegraaff 2013; Wasson et al. 1986). These materials have been employed for centuries to induce spiritual experiences, including shamanic visions, mystical states, and religious ecstasies. Moreover, they have played a role in inspiring literature and art, delving into the realms of spirituality. Beyond the Russian Conceptualists, one may recollect numerous international writers and poets who have turned to entheogens like ayahuasca, psilocybin, and peyote as potent tools for accessing deeper levels of consciousness and exploring the concealed nature of reality. My essay concentrates on the psychedelic ritual utilization of mushrooms, as expressed in the Russian esoteric Conceptualism of three generations. This fungal/mushroom tradition has given rise to many literary texts, artistic objects, and creative performances (Ioffe 2020).

An eminent Russian scholar, a semiotician, linguist, and cultural historian Vladimir Toporov, in his groundbreaking “long-read” article on the mythology of mushrooms and Slavic religious themes (Toporov 2004; See also Elizarenkova and Toporov 1970; Belova 1995), outlined the primary framework and focal points of this entire discussion. Members of all Moscow Conceptualism groups, whose works bear traces of what we term ‘mushroom religion’, were evidently acquainted with the entire layer of ‘mushroom representations’ outlined by Toporov. The Russian underground’s particular interest in all sorts of fungi and mushroom myth-religion can be traced back to the psychedelic revolution of the sixties and partly the seventies. My recent article on the mushroom and hallucinogenic themes of the novel “Mythogenic Love of Castes” delves deeply into this matter (Ioffe 2020). The fascination with mushrooms has even given rise to a distinct discipline, ethnomycology. The full acquaintance of the Russian Conceptualist milieu of both Moscow and Leningrad with various mushroom theories of various historical sorts including the scholarly works of R.G. Wasson and V.N. Toporov is today generally well established (Ioffe 2013, 2017, 2020; see also Nekhoroshev 2021).

My previous essay on the related subject (Ioffe 2020) seeks to offer a general overview of ethnomycology, analyzing the contributions of scholars who have pioneered a new approach to studying hallucinogens of mushroom origin (such as Richard Evans Schultes, Michael Harner, Roger Heim, Peter Furst, etc.) and, more significantly, exploring the cultic role of mushrooms in ritual and mythological practices and systems. Undoubtedly, a critical aspect is the potential fungal nature of the brew-drink ‘soma’, the divine elixir of happiness and immortality mentioned in the ancient philosophical teachings of mankind, specifically the Vedas. One may not fail to add that the fungal origin of soma is only one of the existing hypotheses. To some scholars, it still appears not the most probable heuristic version. Often, based on the Vedas, researchers claim the plant origin of soma (from ephedra or hemp). The word “soma” itself possibly originates from a verb meaning “to squeeze.”8 The ritual for preparing soma presumed that the plant from which it was allegedly made was soaked in water, then squeezed using crush stones, strained through a sheep’s wool sieve, diluted with water, mixed with milk or barley, and then the finished product was poured into wooden vessels. To some critics, this may indeed not necessarily seem like a typical recipe for preparing some peculiar sort of mushroom brew.

A comparative analysis of soma and other mushroom substances structures the foundation for the conceptualist examination and creative representation of various mushrooms, with particular emphasis put on the fly agaric, identified by R.G. Wasson as the probable derivative of Soma9 among various hallucinogenic mushrooms. Wasson was well acquainted with Russian mushroom traditions via his wife Valentina Pavlovna (Wasson and Wasson 1957) and thanks to his friendship with Roman Jakobson, whom he knew quite well. Russian American Professor Vyacheslav Vs. Ivanov later recalled that Jakobson informed him about how his close friend, the banker Wasson, persuaded Claude Lévi-Strauss, a prominent French linguist and anthropologist, to consume the so-called magic mushrooms. Later, Wasson admitted that it was Roman Jakobson who, as early as the mid- 1940s, shared his informed ideas about the religious role of fungi in the prehistory of European humans. According to Wasson, Roman Jakobson continuously disseminated his ideas about mushrooms, including quotes from books, names derived from mushrooms, and rare and archaic nominations of mushrooms in Russia (Wasson et al. 1986; Wasson and Wasson 1957; Wasson 1956; see also Nekhoroshev 2021).

As observes Christopher Partridge, Terence McKenna argued that hallucinogenic mushrooms are the key to understanding the evolution of the entire human consciousness, be it religious or otherwise. It may be further compared to some sort of an “alien Gnosis”. Accordingly, “spores, which had drifted across the frozen vastness of space, settled in cow manure around the communities of our ancestors”. Afterwards, when fungi were successfully consumed, they effectively introduced the “divine spark” that led to the emergence of the modern human esoteric and exoteric consciousness. “There is a hidden factor in the evolution of human beings … that called the human consciousness forth from a bipedal ape”, which “involved a feedback loop with plant hallucinogens” (McKenna 1991). Mushrooms are, in other words, “repositories of living vegetable Gnosis” (McKenna 1992). Moreover, because “psilocybin is a source of Gnosis” (McKenna 1991, p. 97) it enables an understanding of “the eternal nature of the mind” and how to “release it from the monkey” (McKenna 1991, pp. 41–42). Hence, while “the monkey body has served to carry us to this moment of release”, psychedelics enable us to look forward to “the transcendence of physis, the rising out of the Gnostic universal prison of iron that traps the light: nothing less than the transformation of our species” (McKenna 1991, pp. 95–96) (see more context and details in (Partridge 2019)).

2.1. Mushrooms, Humans, and Religious Systems: Analytical Observations

A mushroom-related, “fungal” religious role is undeniable, even more so the esoteric dimension of it. Chapter 29 of Irenaeus’s paradigmatic Adversus Haereses provides one of the first metaphoric comparisons of esoteric religions with fungi: “…from among the aforesaid Simonians, a multitude of Gnostics arose under Barbelo, and they appeared as mushrooms growing from the earth where they had been conceived” (Super hos autem, ex his qui praedicti sunt Simoniani multitudo Gnosticorum Barbelo exsurrexit, et velut a terra fungi manifestati sunt, quorum principales apud eos sententias enarramus) (Irenaeus 1907, pp. 278–79). It is of course not immediately possible, based on a certain idiomatic expression, to postulate a vivid connection between Gnostic teachings and the real fungi. This might very well appear as a linguistic metaphor expressed by means of some local idiosyncratic phraseology. The conceptology of the ‘underground’ here metaphorically signifies the diabolical origin of heretical teachings that are further compared with mushrooms. This in its turn exemplifies the important role mushrooms played in the human operational existence of that time. The human condition of that era readily embraced the very possibility of such a transgressive comparison: a fungus with a living person and vice versa.

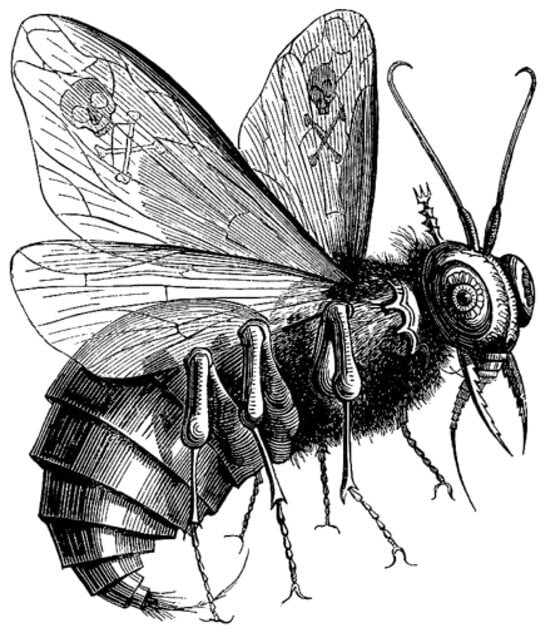

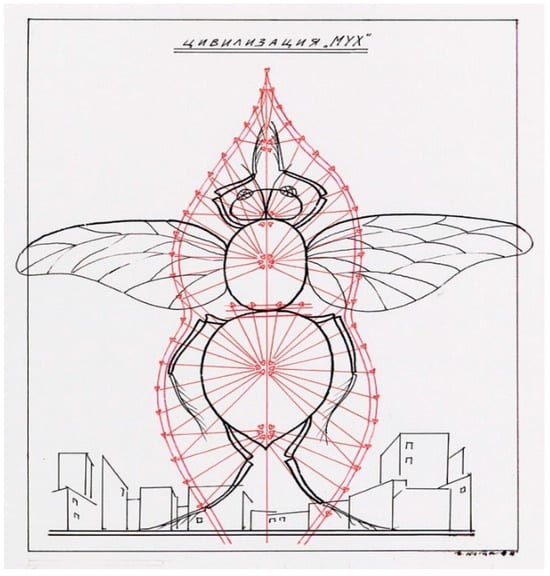

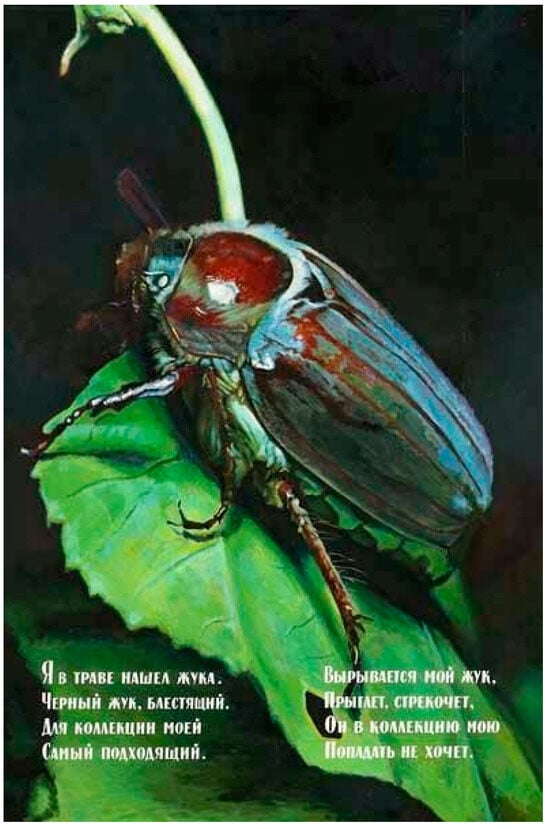

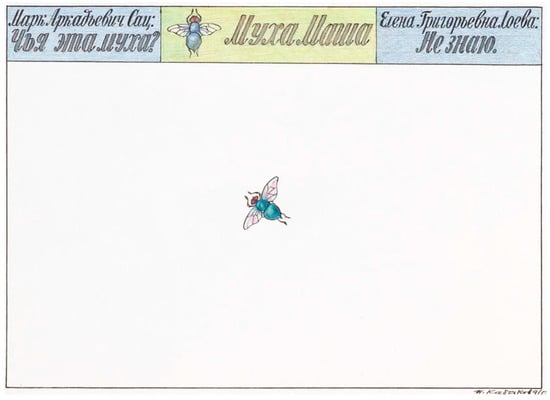

In what follows, this paper postulates and further reinforces an intimate transcultural link between fungi and muscas (Figure 20). Mushrooms and flies are (inter)connected through their ecological relationship, specifically in the context of decomposition and nutrient cycling in ecosystems. In the complex process of decomposition, flies, particularly species like fruit flies (Drosophila), are powerfully attracted to decaying organic matter, including various rotting fruits, vegetables, and multiforme plant material. Mushrooms, as fungi, perform a crucial role in decomposition by breaking down organic substances, including dead or decayed plants and trees. As mushrooms gradually decompose organic material, they de facto give birth to a polyvalent environment extremely rich in nutrients that attracts flies seeking food and breeding dwellings. During the lifecycle, some species of flies, such as fungus gnats, develop a peculiar symbiotic relationship with fungi, thereby illustrating the interdependence of these species. The larvae of these flies often feed on the mycelium or spores of fungi. In this way, flies meaningfully contribute to the dispersal of fungal spores, aiding in the reproduction and distribution of mushrooms (Thomas 1942).

It is thus practically and etiologically impossible to firmly separate flies from mushrooms. One may also remember the so-called nutrient cycling when mushrooms, through their decomposition activities, release nutrients back into the soil, which can then be utilized by plants for growth. Flies, by aiding in the breakdown of organic matter, contribute to the cycling of nutrients within various ecosystems. The nutrients released from decomposing matter by mushrooms can also serve as food sources for fly larvae, completing the nutrient cycle. In the end, it relates in general to the ultimate ecological balance, i.e., the relationship between mushrooms and flies is part of a larger ecological balance within ecosystems. Flies help to break down organic matter, while mushrooms facilitate this process and utilize the resulting nutrients to support their vital growth. This interconnectedness contributes to the overall varieties of health and functioning of ecosystems. One may normally conclude that mushrooms and flies are intrinsically mutually connected through their roles in decomposition, nutrient cycling, and ecological interactions within ecosystems. They form part of a complex bio-web of relationships that sustain life and contribute to the functioning of natural systems (Thomas 1942).

As we can ascertain, mushrooms have been broadly revered and used in various religious and spiritual practices throughout history, particularly in indigenous cultures where they are often seen as powerful, albeit ambiguous and suggestive, symbols of fertility, healing, or spiritual enlightenment (Wasson 1971; Schultes 1976; Ioffe 2020; Belova 1996; Dikson 2008; Heinrich 2002; Stamets 1996). Mushrooms sometimes also bear an extremely intriguing social symbiotic value as well (see the recent study: Tsing 2021). Many indigenous peoples in the Americas have used edible as well as hallucinogenic mushrooms in religious ceremonies for centuries. Flies, on the other hand (aside from Beelzebub, on which topic see below) are less commonly associated with religious or spiritual symbolism, though they may have significance in certain cultural contexts10. In several ancient Egyptian and Greek mythologies, flies were associated with decay and death, while in other cultures, they may be seen as symbols of annoyance or pestilence. Russian Conceptualism, and especially Makarevich–Elagina on the one hand and Kabakov on the other, in de facto proposes such an esoteric religion centered around mushrooms and flies, playfully incorporating themes of transformation, decay, regeneration, and the interconnectedness of all living beings. Jean-Paul Sartre famously expressed a somewhat parallel attitude in his suggestive war-time theatre play (1943) Les Mouches.

It is noteworthy that the general essence or classification of mushrooms is still a debated and rather ‘loaded’ topic in scientific mycology. As Vladimir Toporov notes, in various religious narratives, mushrooms act as representatives and mediators among distinct entities—mineral, vegetable, animal, and, in some unique cases, human. Mushrooms, omnipresent and versatile, can be consumed or revered, serving as universal nutritional substitutes for various things. Mushrooms in folk demonology are living creatures (Figure 21 and Figure 22) that have the gift of speech, in the forest you can hear them talking or squeaking. In some Slavic traditions, mushrooms correspond with mythical characters, like mythical bogatyrs or giants or, on the contrary, ambiguous dwarfs (one may mention the Polish czerwonolicy legendary human gnomes, which God, for some reason, turned into mushrooms). Sometimes, mushrooms are more clearly correlated with shapeshifters, witchery, and the devil (szataniak, duibelnik, chertouo vajce, chertovo hovno), in particular werewolves (vrkolak). The careless handling of Slavic mushrooms can be the cause of a devil that flies out of a large mushroom, or its black goat with golden or branching horns. The provocative behavior of wild fungi in the plant world is similar to that of sorcerers among humans. Masluszki survive other living creatures from the forest with the help of a certain “lich”, ingest their “milk”, and strangle them, while ssawki, clinging to people, suck away their strength and absorb their spirit. (See Belova 1995).

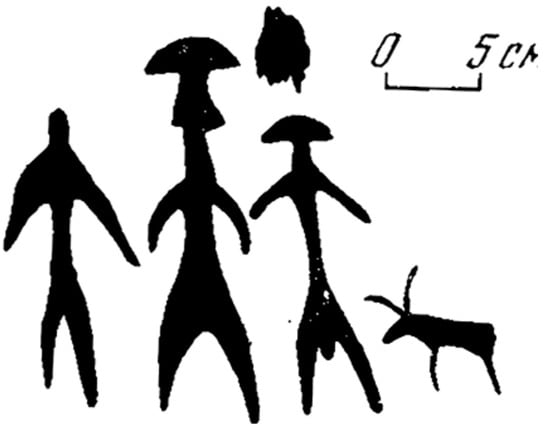

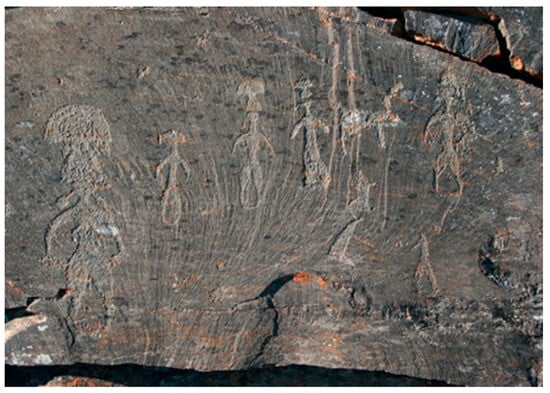

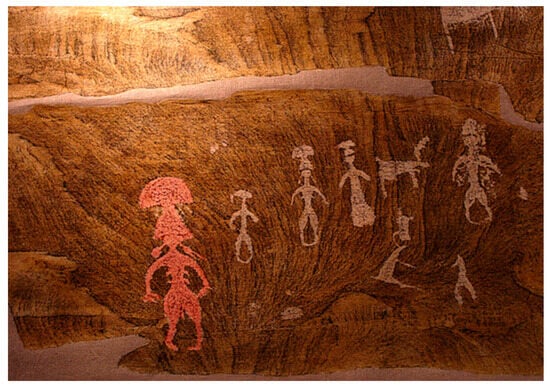

The complicated transgressive relationship between mushrooms and humans, as Toporov explores, involves all the traditional aspects of anthropomorphism, with mushrooms symbolizing individuals, particularly gods, being hiddenly divided also into male and female categories. As my previous research demonstrated, in some parts of the Russian empire, there existed beliefs based on a strong mythological and religious syncretism between mushrooms and men. Such was the notion of the so-called Liudi Mukhomory (Fly Agaric Men) (Cf. also Wasson 1967; Ioffe 2020). Here, one may refer to the renowned rock paintings attributed to the fly-agaric cult within the Paleo-Yeniseian culture. These depictions, resembling some odd “dancers”, originate from the Sayan Canyon of the Yenisei and the Mogur-Sargol tract (Figure 21, Figure 23, Figure 24 and Figure 25). The anthropomorphic, mushroom-shaped figures from Pegtymel in Chukotka present iconographically distinct representations, characterized by wide-brimmed hats that visually replace their heads. These images are distributed along both banks of the Chinge River and the Yenisei River in the Mogur-Sargol tract. The Mukhomor figures appear to be in perpetual motion, seemingly engaged in an enigmatic dance (Figure 25), often accompanied by animal figures. A peculiar vertical object at their waists may be suggestive of a phallic symbol. See below the photos of the ancient Siberian petroglyphs depicting this unique breed of fungi and humans as rendered in my 2020 article.

Figure 23.

Ludi-Mukhomor (Human-Amanita muscaria) at Chukotka archaeological site, reproduced in (Ioffe 2020).

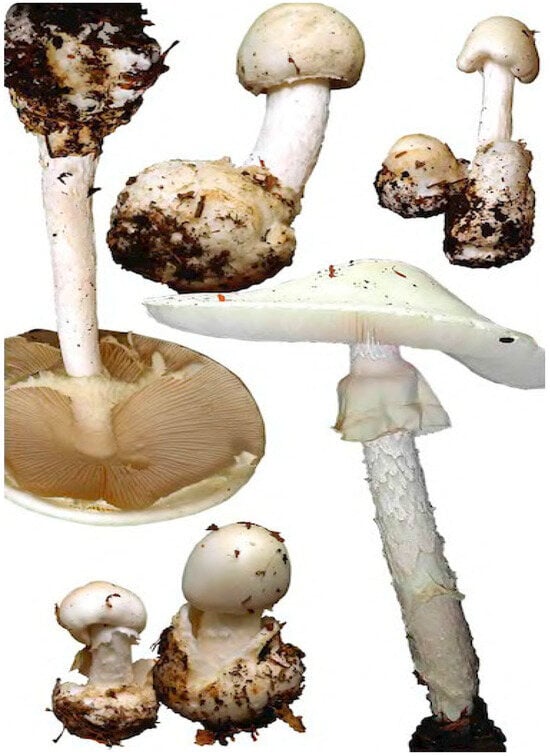

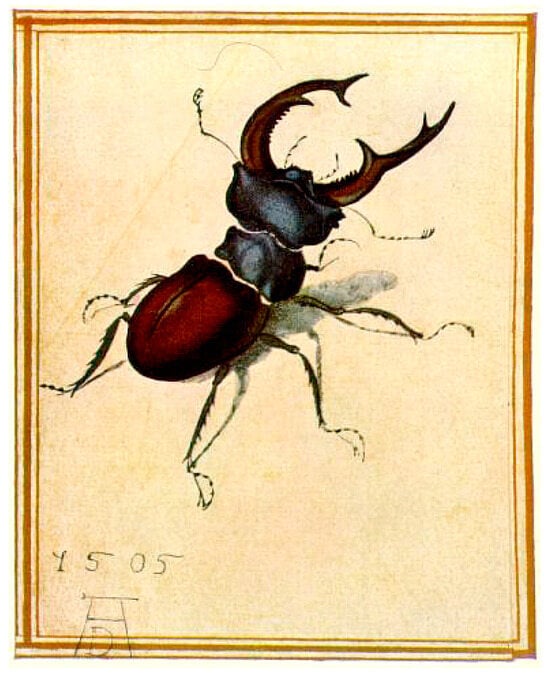

The virtual link between the fly agaric mushroom (mukhomor) and actual flies may stem from its historical use as an insecticide. Across Europe, it was common to sprinkle this mushroom in milk to eradicate flies, a practice recorded by Albertus Magnus around 1256 in his magisterial work ‘De vegetabilibus’. Linnaeus initially labeled it as ‘the mushroom of flies’, Agaricus muscarius, but Lamarck later in his turn voluntary renamed it Amanita muscaria while establishing the very Amanita genus (Harding 2008; Dugan 2008). The name phonetically resembles ‘amanta’, suggesting a certain link to fly-attraction, possibly with sexual connotations embedded inside. Historically, Amanita muscaria was utilized as a mighty bug repellent in England and Sweden, which is reflected in alternative names like ‘bug agaric’. French mycologist Pierre Bulliard attempted to emphasize its insect-repelling properties in 1784, proposing the name Agaricus pseudo-aurantiacus, albeit unsuccessfully (Harding 2008; Gurevich 1993). Flies might be drawn to Amanita muscaria due to its fluid intoxicating effects, though another theory suggests the term ‘fly’ relates to the certain magic delirium induced by consuming the fungus, rooted in medieval beliefs associating flies with mental illness. Regional folk and pagan variations further enrich its suggestive symbolism. Some names like ‘mad’ or ‘fool’s’ versions in Catalan and Trentino (Italy) hint at this interpretation, while in Fribourg, Switzerland, it is known as ‘tsapi de diablhou’ meaning ‘Devil’s hat’ in the local dialect (Dugan 2008; Ruck 2011). In Russian and many Slavic and Baltic languages, the name directly means more or less ‘destroying flies’, reinforcing its insecticidal reputation. However, in some Slavic languages, it is merely associated with flies without implying extermination, creating a peculiar mix of attraction, intoxication, and death, reminiscent of esoteric cults.

Aside from fungal–human organic links, the possible correlation between mushrooms and divine entities proves to be exceedingly significant. Notably, in several cultural and religious representations, mushrooms, characterized as a miraculous “gift of the gods”, are intricately linked to the offspring of the archetypal godly Thunderer. Providing the necessary myth-religious details, Vladimir Toporov (2004), carefully explores the historical evolution of this concept. He enters in more scrupulous detail into the widespread belief among Greeks and Romans that mushrooms grow not because of rain but as a result of thunder, a notion validated by analogous reports from regions such as India, Kashmir, Iran, the Arabian Bedouin territories, the Far East, Oceania, and among Mexican Indians. Two noteworthy categories of cases emerge from this data: first, instances where the connection with thunder, lightning, and rain is reflected in the mushroom’s popular nomenclature (or when the terms for the mushroom, lightning, and thunder share linguistic similarities); and second, cases where distinctive mushroom rituals have been commonly preserved. The broad picture of hallucinogenic and ethnological mushroom-related encounters with humans is available in a wide variety of studies: (Wasson 1967; Shanon 2002; Schultes et al. 2001; Schultes 1976; La Barre 1990; Heinrich 2002; Harner 1973; Gordeeva 2017; Elizarenkova and Toporov 1970; Allen 1997; Batyanova and Bronshtein 2016; Batyanova 2001a, 2001b).

According to Toporov, examples falling into the first category include typical mushroom names such as Russian ‘gromovsh’, ‘dozhdevik’ (mushroom rain), or Slovene ‘molnjena gob’, and probably Amanita muscaria (Ippolitova 2008). The Māori term ‘whatitiri’ carries dual meanings of ‘thunder’ and ‘mushroom’, with the name of the mythical ancestor-girl being ‘Whatitiri’, and her grandson, Tawhaki, producing lightning from his armpits. As Toporov remarks, in Pampanga, the mushroom’s name contains the element ‘kulog’, meaning ‘thunder’, similar to some specific Chinese names reported in the 1811 History of Mushrooms written in Japanese. Additionally, a prevalent motif concerns the origin of mushrooms from god’s spittle, akin to the origin of plants, and further connections with mushrooms as god’s excrement and their association with heavenly urine. The Somang hunting tribes of the Malacca Peninsula believe that the sky god Kari scatters animal souls like seeds on the ground; where they fall, mushrooms emerge. Poisonous mushrooms, according to prevalent beliefs, harbor the active souls of animals perilous to humans (See Toporov 2004).

2.2. New Age Esotericism, Gnosticism, and the World of Fungi: The Problematics of Spermic Religious Imagery

Normally, the terminology of New Age Esoteric Religion refers to an international spiritual movement that emerged in the latter half of the 20th century, drawing from various religious, philosophical, and mystical traditions, often incorporating elements of Eastern spirituality, Western Occultism, and alternative metaphysical practices. It typically emphasizes (and epitomizes) personal spiritual growth, inner transformation, and a holistic approach to existence that integrates mind, body, and spirit. From a scholarly perspective, New Age Esoteric culture can be grasped as a socio-cultural phenomenon characterized by a rather eclectic syncretism, with disparate beliefs and practices merged into a new body of thought. It often involves the adoption of exotic spiritual beliefs and practices that are not necessarily rooted in empirical evidence or mainstream scientific understanding. However, New Age spiritualism may occasionally incorporate elements of psychology, neuroscience, and quantum physics when seeking some rational basis for its worldview. Overall, New Age Esoteric Religion, if it existed, should reflect the human primordial quest for reciprocal semiosis of meaning, transcendence, and connection to something beyond the ordinary mind, albeit often outside the scope of conventional intellectual inquiry (see Hanegraaff 1996, 2022; Radulović and Hess 2019).

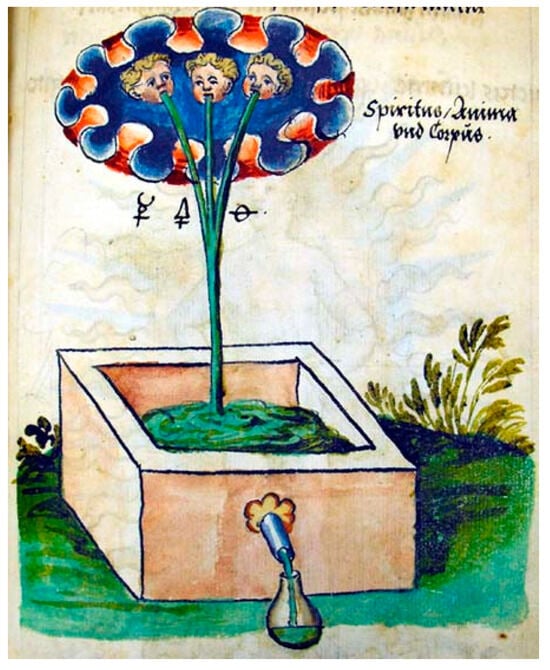

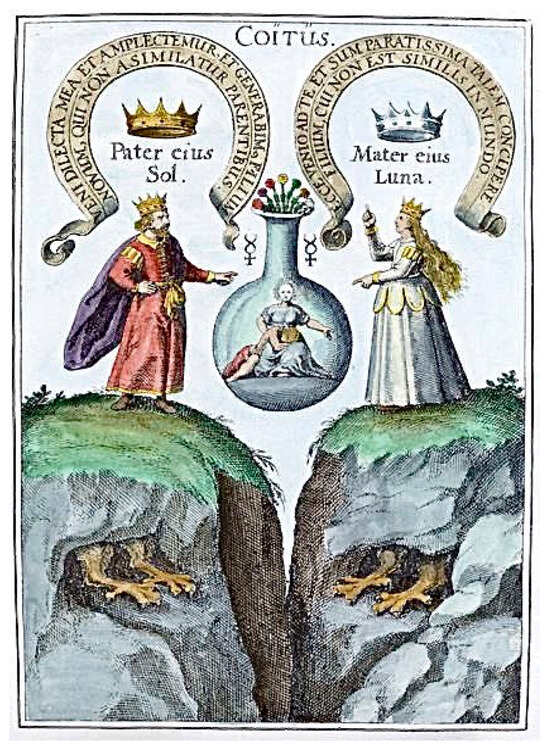

Esotericism permeates the fabric of diverse global cultures, representing the suggestive reservoir of ideas concerning the divine, the cosmos, and humanity, divulged through revelation and reserved for the enlightened few (Figure 26). Generally, the esoteric realm encompasses Hermeticism, Occultism, and a historic segment of the Gnostic legacy. Hermeticism, rooted in the Greco-Egyptian tradition, delineates a framework of cosmological concepts preserved in what is often termed as the Corpus Hermeticum, attributed to the legendary divine sage Hermes Trismegistus. This intricate esoteric system of thought traces its lineage through millennia, offering insights into the nature of existence and the mysteries of the universe (Hanegraaff et al. 2019; Van den Broek 1998, 2013; Hanegraaff 2012, 2016, 2022; Faivre 2010; Versluis 2004). Occultism, on the other hand, encompasses pragmatic methodologies aimed at manipulating the fabric of reality through an active collaboration with supernatural forces (Gunn 2005; Page 2013). It serves as a pragmatic conduit for those seeking to exert crypto influence beyond the constraints of conventional understanding. The perception of Gnostic doctrines has evolved over time, initially branded as Christian heresies (Churton 2015). However, discerning minds, such as Harnack (1901) delineate a distinction between Gnosis, an esoteric mode of comprehension, and Gnosticism, a second-century movement emerging from within Christian obscure sects. The delineation between these traditions remains fluid, with overlaps and interplay evident throughout history. Scholars recognize the multifaceted nature of Hermeticism, distinguishing between its scientific, philosophical, and ‘popular’ manifestations, the latter encompassing disciplines such as astrology, alchemy, and magic. Similarly, Gnosticism intertwines with magical practices, exemplified by figures like Simon the Magus, who is hailed as a progenitor of Gnostic deviations (Van den Broek 2013; Trompf 2019; Hanegraaff 2016). Conversely, occult sciences draw upon philosophical underpinnings, evident in traditions like alchemy and the neo-Occultism espoused by figures such as Eliphas Levi. Even within the Corpus Hermeticum, parallels to Gnostic tenets emerge, underscoring the interconnectedness of these esoteric traditions. In essence, esotericism transcends temporal, cultural, and even national boundaries, offering a diverse tapestry of insights into the profound mysteries of existence, while simultaneously blurring the distinctions between disciplines and belief systems (Johnston 2014; Hanegraaff 2012, 2022; Forshaw 2017).

As Wouter Hanegraaf has once remarked, Hermetic practitioners “believed that the horizon of human consciousness could not just be expanded but could be transcended altogether, resulting in those states of absolute knowledge and direct insight to which they referred as gnosis” (Hanegraaff 2022). As another scholar has aptly put it, the modern mystics, “imagined as part of a stream that flowed back to Origen and Dionysius the Areopagite, presented as a small club with a few exemplary members, especially William Law, Jacob Boehme, Jeanne Marie Guyon, Antoinette Bourignon, Miquel de Molinos, Francois Fenelon, and Pierre Poiret” and many others (Schmidt 2003).

It is important to mention that the term Occultism was initially used in 1842 to be later accepted on a larger literary scale. During the first decennia of the 19th century, the usage of esotericism as a noun (ésotérisme) was promoted by Jacques Matter in “Histoire critique du gnosticisme et de son influence” (1828). As Wouter Hanegraaf points out, the adjective esoteric goes back to the second century (Lucian of Samosata), while currently it is used extremely broadly (Hanegraaff 2016). Today, the historical studies from the field of Western esotericism could be normally merged with explorations of new religions, pagan studies, in order to achieve a compete and adequate analytic picture (Asprem and Granholm 2013; Asprem 2021).

For the topical purposes of the current essay, I broadly utilize the suggestive term entheogens which came to scholarly attention (among others) with the studies of Gordon Wasson. As Wouter Hanegraaff points out, the noun entheogen was seemingly firstly coined in 1979 “by a group of ethnobotanists and scholars of mythology who were concerned with finding a terminology that would acknowledge the ritual use of psychoactive plants reported from a variety of traditional religious contexts, while avoiding the questionable meanings and connotations of current terms, notably hallucinogens and psychedelics” (Hanegraaff 2013). These substances generate special states of consciousness “in which those who use them are believed to be ‘filled’, ‘possessed’ or ‘inspired’ by some kind of divine entity, presence or force” (Hanegraaff 2013). This may go back to Paracelsus and his thoughts on the special “synthesis of physical body, immortal soul, and sidereal (or astral) spirit” (Moran 2016). Speaking of entheogens forces one to bring the concept of magia naturalis and the many perturbations the ideas of magic were undergoing through the centuries (Hanegraaff 2012). As many scholars emphasize, it is uneasy to point out “what distinguishes religion from magic”. At the same time, it could be said “that magic tends to grow on a substratum of religion, like a fungus, and that it is able to adopt religious ceremonies and divine names” (See Luck 2006, p. 2; see also Frankfurter 2019).

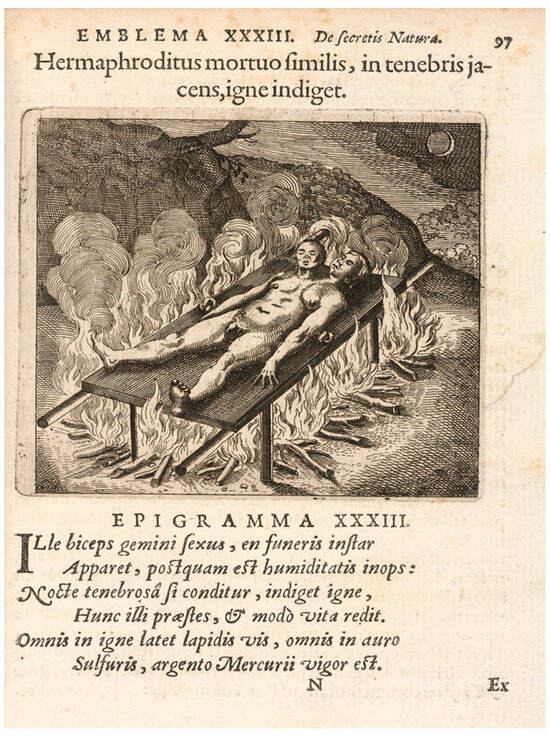

Esoteric magic, human–mushroom anthropomorphic syncretism raises a broader imagery of artificial suggestive entities, created in the context of human manipulations with the realm of the divine/demonic forces (Dunn 1973; Clark 1999; Heinrich 2002; Ioffe 2020). In the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the concept of the alchemical humanoid or homunculus emerged as a hypothetical creation pursued by alchemists (Figure 26). The homunculus was envisioned as a miniature, fully formed human being produced through alchemical processes. Alchemists believed that by manipulating various substances and performing specific rituals, they could generate life artificially in the form of the homunculus. The creation of the homunculus was often associated with the quest for the Philosopher’s Stone (on which below) and the elixir of life (possible human semen, or logos spermaticos, on which below), as alchemists sought means to achieve immortality and unlock the secrets of existence. However, it appears to be crucial to observe that despite fervent speculation and experimentation, there is no historical evidence of any clinically successful homunculus creation. The very concept of the homunculus became intertwined with alchemical symbolism and mystical beliefs, reflecting the broader fascination of our entire era with the mysteries of life, creation, and transformation. It also served as a mighty metaphor for the very alchemical quest itself, symbolizing the aspiration to transcend natural limitations, acquiring the unique mastery over the fundamental forces of nature (Van den Broek 1998).

The notion of the alchemical humanoid, known as the homunculus, remained somewhat enigmatic throughout the High and late Middle Ages, yet found notable elaboration in Paracelsus’s famous seminal work, ‘De natura rerum’ (circa 1537). In this treatise, as Roelof van den Broek has remarked, Paracelsus powerfully articulates his views on a depiction of the homunculus that bears eye-catching resemblances to elements found in ninth-century Pseudo-Plato’s ‘Liber Vaccae’ (‘Kitāb Al-Nawāmīs’ or ‘The Book of the Cow’), an obscure magical text of significant heuristic importance. These parallels encompass various facets such as the utilization of human sperm, an incubation period of forty days, the nourishment of the incipient being with blood, and its purported capacity, upon maturation, to unveil mystical and alchemical secrets. It is plausible that Paracelsus drew inspiration from the ‘Liber vaccae’, suggesting a cross-pollination of ideas between alchemical and magical traditions of the era. Moreover, the Jewish historical folklore surrounding the Golem, an artificial human-like essence, shares intriguing resemblances with the experiments detailed in the ‘Liber vaccae’ (Figure 27) (Van den Broek 1998).

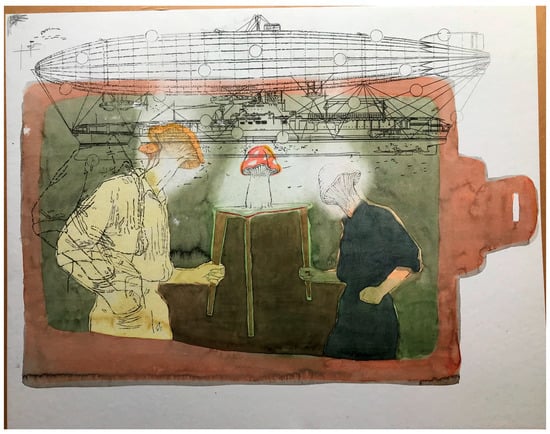

The alignment of these storylines highlights the profound intrigue that medieval and Renaissance esoteric intellectuals held towards artificial life, alongside their exploration of the enigmatic domains of alchemy and magic (Figure 28, Figure 29, Figure 30, Figure 31 and Figure 32). This convergence serves as compelling evidence for the interconnected nature of various streams of thought during this era. It underscores how scholars of the time were deeply engaged in probing the boundaries between natural and supernatural, seeking to unravel the mysteries of existence through both empirical and mystical lenses. The fascination with creating life artificially, intertwined with the pursuits of alchemical transformation and magical practices, demonstrates a holistic approach to understanding the universe, where scientific inquiry and metaphysical exploration were intertwined. As the eminent Dutch historian of religions Roelof van den Broek justly observed, the Golem-making undertaking was perceived as “permissible magic”, as a very important Israeli historian of Jewish mysticism Moshe Idel stressed, “usually appearing in stories of the extraordinary deeds of legendary rabbis” (Van den Broek 1998; see also Bohak 2007).

The tale of the Golem, depicted as a humanoid entity crafted through mystical means, emerges towards the close of the twelfth century, although the notion of fashioning artificial beings, including humans and cows, finds its roots in earlier epochs. Within this tradition, Adam serves as a pivotal figure, resonating particularly in the ‘Liber vaccae’. In Talmudic Aggadah, Adam is portrayed as akin to a Golem during the initial stages of his formation—a shapeless entity awaiting the divine breath that would grant him life and speech. References to human components in the ‘Liber vaccae’ experiments are made in relation to the line of Adam, alluding to the creation of artificial entities and the first human. As Roelof van den Broek observes, the possible parallel could arise between the Jewish mystical intention to fabricate humanoid creatures and those mentioned in the Liber vaccae, where discussions on crafting artificial humans coexist with accounts of creating artificial cows—a notable example being the Jewish legend of the so-called ‘sabbath-calf-offering’. Furthermore, these quests may be somehow interwoven with the mystical practices of Harrān. This juxtaposition of suggestive themes signifies a profound intersection of mystical lore, scientific inquiry, and theological contemplation. According to the Dutch scholar, it exemplifies the intricate web of influences shaping medieval and Renaissance thought, where narratives of creation, both divine and human-wrought, blur the lines between the natural and the supernatural. The incorporation of magical traditions from diverse cultural and religious backgrounds further enriches this tapestry of intellectual exploration, highlighting the universal human fascination with the mysteries of life and perpetual creation (Van den Broek 1998).

As Roelof van den Broek pertinently remarks, “thirteenth-century German Hasidim who commented on the Sefer Yetsirah interpreted the souls they [Abraham and Sarah] had made in Harrān as beings magically created by Abraham in the tradition of golem making (Figure 33). On this tablet stands the following text: ‘Hermes the Prince. After so many wounds inflicted on humankind, here by God’s counsel and the help of Art I flow, a healing medicine” (Van den Broek 1998). It can be readily deduced from this inscription that Hermes is symbolically represented as some sort of the aqua permanens of the alchemists, that is to say, the “philosophical mercury” (mercurius philosophicus), which is also named the “water of life” (aqua vitae). That is why the tablet invites one to drink from this wonder water: “Drink, brothers, and live” (‘Bibite fratres et vivite’) (Van den Broek 1998). In addition to this, discussing the ‘Origin of the World’ of Nag Hammadi, Roelof van den Broek has addressed the emergence of a certain “Valentinian world” which is introduced by a passage about the birth of a real Eros, an androgynous figure, represented as the mighty inspiration of sexuality and the human reproductive urge, which should be in their turn strongly rejected. It is to him that “not only people but also plants and animals owe their existence” (Van den Broek 2013). The oral consummation (drinking) of sperm or smearing semen over one’s body as a part of a sacral act appears to be a rather characteristic aspect of these Gnostic attitudes. John Allegro’s hypothesis about the early Christian sect of Essenes (who were related to Gnostic heritage) appears therefore less outrageous as it might have been evaluated in the first instance.

Within this highly allusive esoteric contextual framework emerges a significant and provocative figure of John Allegro, an eminent academic historian of ancient Christianity, a semitologist, and an archaeologist. Notably, his groundbreaking ‘psychedelic’ scholarly work seems to have captivated the attention of Moscow Conceptualists from different generations, including both Andrei Monastyrsky’s and Pavel Peppershtein’s artistic cohorts (Ioffe 2020). Allegro, once a renowned British archaeologist and researcher of the Dead Sea Scrolls, garnered global recognition for his unconventional theories, particularly his interpretation of crucial religious personifications and symbols as allusions to psychoactive mushrooms. As part of an international team working on the publication of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Allegro’s revolutionary views, presented in his 1970 book “The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross”, (Figure 34) posited an unorthodox connection between the origins of primeval Christianity and the ritual use of psychoactive mushrooms, specifically the secret veneration of the “crucified fly agaric” (in imagination or in reality).

Allegro argued that the story of Jesus and other religious symbols and myths were nothing but allegorical representations of peculiar fungal esoteric cults and universal rituals of orgiastic sexuality and fertility. He contended that ancient religious texts, including the Bible, concealed the true nature of these psychedelic rituals, suggesting that the term ‘Christ’ itself had a concealed meaning grounded in an ancient Semitic root denoting subversive mushroom activity. Allegro interpreted various sacred (also apocryphal) stories, such as the virgin birth and the Last Supper, as symbolic representations of rituals originally associated with visionary mushroom practices, positing that the word ‘Christ’ itself is rooted in a mysterious crypto-nomer denoting a particular mushroom, and the biblical stories are essentially symbolic Semitic narratives of various hallucinogenic experiences.

John Rush in his turn proposes an exceedingly challenging perspective that diverges from traditional perceptions of Jesus Christ. Essentially refusing to regard Jesus as a real historical figure, Rush seems to suggest that early Christians conceived of him as a symbolic representation of mystical encounters induced by entheogenic substances like psychedelic plants and fungi. According to this interpretation, Christ was not an ordinary individual but rather a manifestation of something else, a personification of the profound spiritual experiences facilitated by these psychoactive substances. This viewpoint implies that the depictions of Jesus in Christian art may symbolize the transformative and even transcendent experiences associated with entheogenic rituals, rather than representing a literal historical figure. Moreover, the notion that Jesus symbolizes the psychedelic urge suggests a deeper spiritual dimension within Christian theology (Rush 2011). It prompts exploration into the potential influence of altered states of consciousness on the development of religious beliefs and practices throughout history. By conceptualizing Jesus as a metaphorical expression of the psychedelic journey, we can potentially reframe our understanding of Christian teachings and their origins (Brown and Brown 2016). This psychedelic perspective challenges conventional interpretations of Christianity trying to engage interdisciplinary research into the intersections of religion, consciousness, and various altered states of mind (Furst 1990). It promotes an unorthodox examination of the historical and cultural contexts in which original semitic religious traditions emerged, shedding light on the intricate relationship between spirituality and psychoactive substances in ancient human societies (Rush 2011). This topic appears to be further elaborated in a Jewish mystical book of Zohar (first disseminated by thirteenth century writer Moses de León with reference to Simeon ben Yochai (Rashbi), a second century sage from the ancient Judea: