The Diverse Health Preservation Literature and Ideas in the Sanyuan Canzan Yanshou Shu

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Diverse Literature Sources

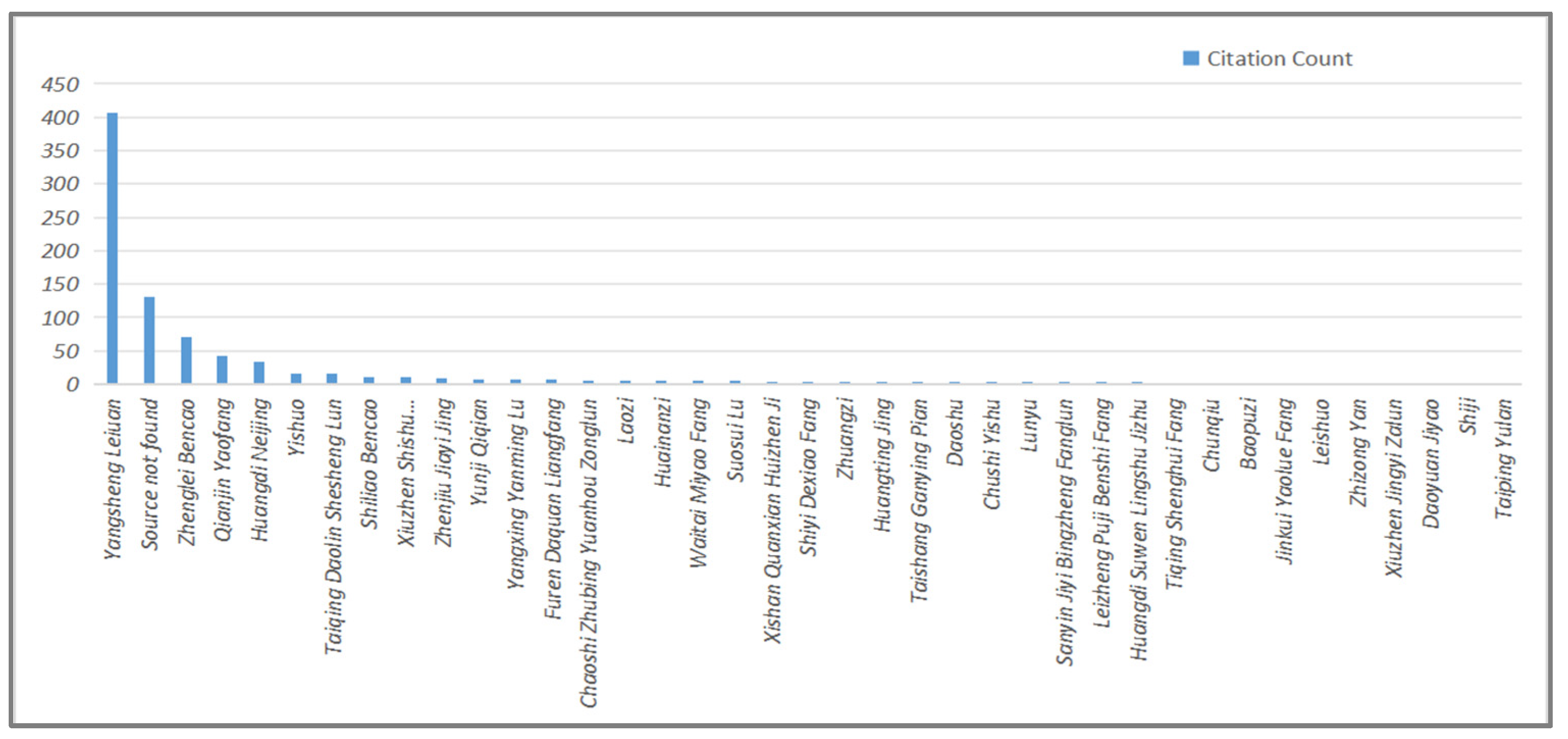

2.1. The Cited Documents of the Sanyuan Canzan Yanshou Shu

2.2. The Sanyuan Canzan Yanshou Shu and the Yangsheng Leizuan

2.2.1. Chapters and Entries

2.2.2. Specific Content

A: It is advisable to refrain from brushing teeth immediately upon waking, as this practice has been associated with potential dental instability, including the mobilization and loosening of tooth roots, which may culminate in toothache. Historically, the composition of toothbrush bristles, often made from horsehair, was implicated in the deterioration of dental health. The abrasive nature of horsehair bristles was believed to corrode the roots of the teeth, facilitating decay, which can be seen in residues of horsehair bristles found in extracted teeth.早起不可用刷牙子,恐根浮兼牙疏,易損極,久之患牙疼。蓋刷牙子皆是馬尾為之,極有所損。今時出牙者,盡有馬尾灰,蓋馬尾能腐齒根。

B: Upon waking, one should sit facing east and rub their hands together until they feel warm. Then, use the hands to rub from the forehead up to the crown of the head, completing twenty-nine full strokes. This practice is properly called preserving the Mud Ball.6早起向東坐,以兩手相摩令熱,以手摩額上至頂上,滿二九,正名曰存泥丸。

C: At dawn, a traditional health practice begins with individuals massaging their ears fourteen times in an up-and-down motion. Subsequently, they pinch their nostrils closed, hold their breath, and with the right hand, pull the left ear from above, repeating this action fourteen times. This is followed by lifting the hair at the temples upward with both hands, which is said to enhance blood and energy circulation and prevent the graying of hair. The final step in this morning ritual is the dry bath, which involves rubbing the hands together until they become warm and then massaging the body up and down. This practice is reputed to alleviate a variety of health issues, including colds, seasonal disorders, fevers, and headaches.清旦初起,以兩手叉兩耳,極上下之,二七止,令人不聾。次縮鼻閉氣,右手從頭上引左耳,二七止。次引兩發鬢,舉之,令人血氣流通,頭不白。又摩手令熱,以摩身體,從上至下,名幹浴,令人勝風寒,時氣,寒熱,頭疼,百病皆除之。

D: When a person rises at dawn, they should always speak of good things, as heaven will then grant them blessings.凡人旦起,常言善事,天與之福。

Walking should not cause one to lose energy. Also, when walking or riding a horse, one should not look back, as this causes the spirit to leave. Whenever one intends to move about, always imagine the kuigang7 above your head for good fortune in all directions. Speaking little while walking, which can prevent the dissipation of one’s spirit and the depletion of energy. Frequently grinding one’s teeth during nighttime walks, without a set number of times, can ward off malevolent spirits and prevent them from afflicting a person. For those fearful in their hearts during night walks or in profound sleep, envision the sun and the moon returning to the Mingtang, so all evil will extinguish itself within a moment, especially good for those living in the mountains. When returning home at night, writing the characters “I’m a ghost” on the palm of your hand with your middle finger of either the left or right hand, then clasping it tightly to dispel fear.行不得令人失氣。又,行及乘馬,不用回顧,則神去。凡欲行來,常存魁罡在頭上,所向皆吉。行不多言,恐神散而損氣。夜行常琢齒,琢齒亦無限數也,煞鬼邪。鬼邪畏琢齒聲,是故不敢犯人。夜行及冥臥,心中恐者,存日月還入於明堂中,須臾百邪自滅,山居恒爾此為佳。夜歸,左手或右手,以中指書手心,作“我是鬼”三字,再握固,則不恐懼。

Semen euryales8 enhance vitality, spirit, and determination, and sharpens hearing and vision. Consumed regularly, it can lighten the body, reduce hunger, and increase resistance to aging. When prepared as a powder, it serves as an excellent food, esteemed as a medicine for longevity. Besides, if fed to children, it can prevent growth, thus stalling aging. Consumed raw, it can provoke rheumatic and cold conditions. Excessive consumption is not beneficial for the spleen and stomach, as it can also be difficult to digest.雞頭,益精氣志,令耳目聰明。久服,輕身,不饑,耐老。作粉食極妙,是長生之藥。與小兒食,不能長大,故駐年耳。生食,動風冷氣,多食,不益脾胃氣,兼難消化。

3. Harmony as the Cornerstone of Health Preservation

3.1. The Principle of Not Diminishing Primordial Pneuma

The dynamic interplay of yin and yang throughout the four seasons encapsulates a profound principle that underlies all existence, acting as a pivotal juncture between life and death. The wise approach is to nourish yang during the spring and summer, because these seasons characterized by growth, expansion, and warmth. Conversely, during the autumn and winter, when the world cools and contracts, it is prudent to nurture yin, supporting the body’s need for conservation and replenishment. To disregard this seasonal guidance by acting in opposition to these natural trends is to fundamentally undermine one’s health foundation and damage one’s essential vitality.夫四時陰陽者,萬物之根本也。所以聖人春夏養陽,秋冬養陰,與萬物浮游於生長之門。逆其根則伐其本,壞其真矣。故陰陽四時者,萬物之終始,死生之本也。逆之則災害生,從之則苛疾不起,是謂得道。

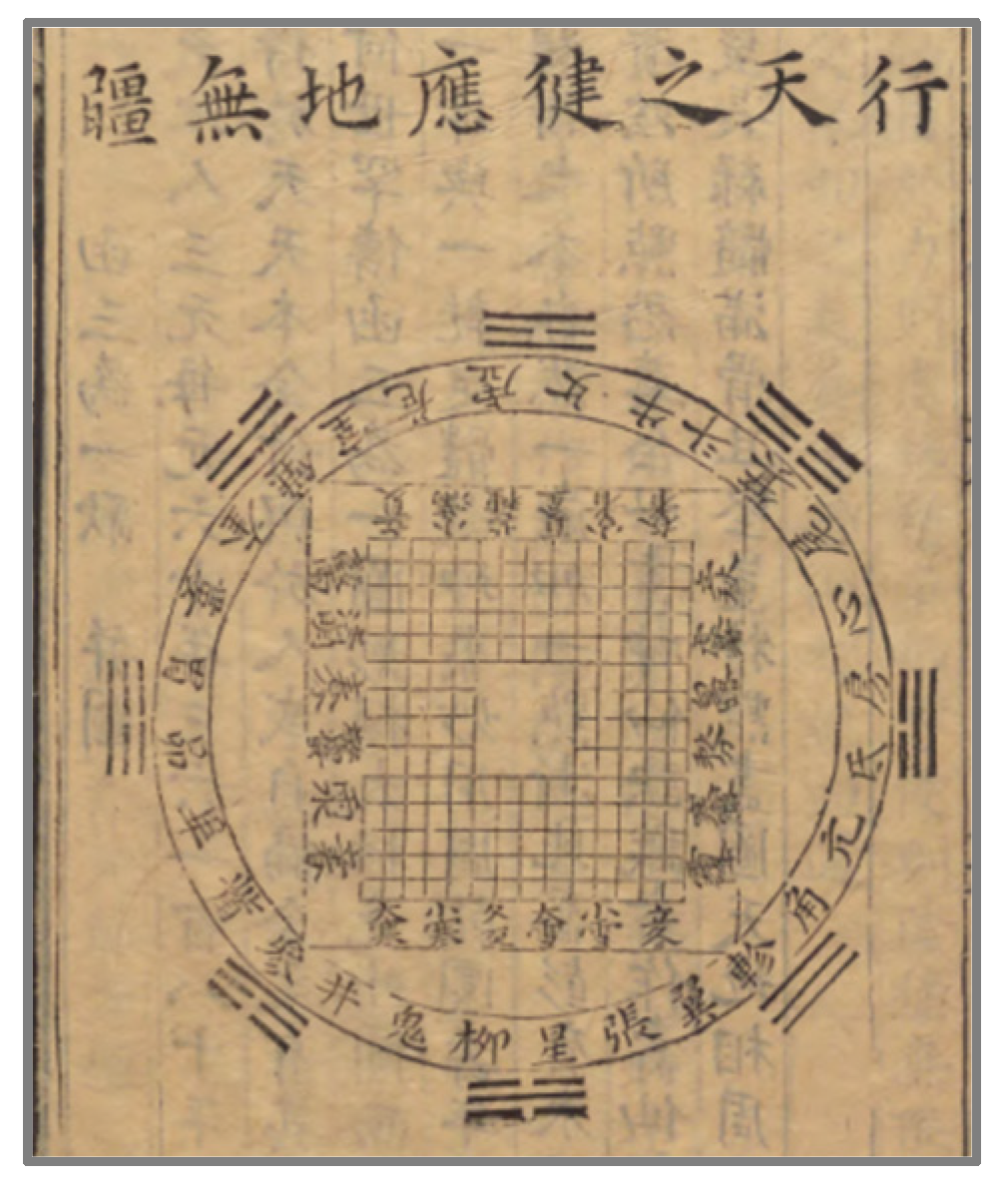

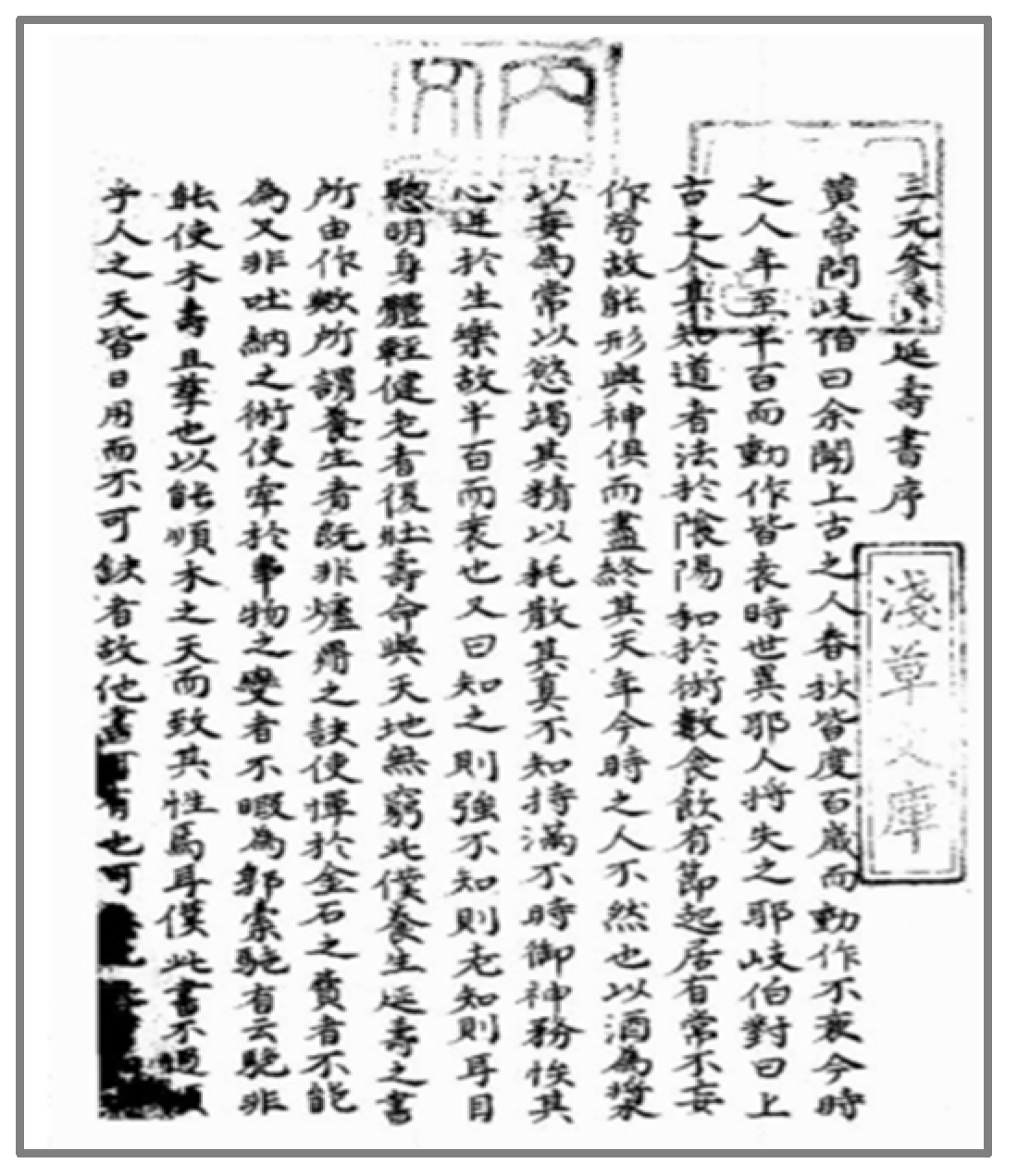

3.2. The Extension of Life through the Three Primes

In ancient times, when the sages made the Yi, they intended to follow the principles of nature and life. Therefore, they established the way of heaven as yin and yang, the way of earth as gentleness and firmness (gangrou 剛柔), and the way of man as benevolence and righteousness (renyi 仁義). Embracing the three powers and dividing them into two, hence the Book of Yi has six strokes to form a hexagram; distinguishing yin and yang, alternating between gentleness and firmness, hence the Book of Yi has six positions to form a chapter.昔者聖人之作《易》也,將以順性命之理。是以立天之道曰陰與陽,立地之道曰柔與剛,立人之道曰仁與義。兼三才而兩之,故《易》六畫而成卦;分陰分陽,迭用柔剛,故《易》六位而成章。

This text posits that while a lifespan of 180 years is divinely bestowed and represents the maximum given, the actual lifespan one achieves is determined by individual actions. The method to attain this full lifespan is exceedingly rare and is epitomized by the principle of Taiji, encapsulated in the Three-in-One diagram. This diagram features a circle on the outside and a square inside, composed of one Kun and one Qian. Longevity is found within this structure, arising naturally from these principles.天地人三元,每元六十年。三六百八十,此壽得於天。天本全付與,於人或自偏。全之有其法,奈何世罕傳。函三為一圖,妙歎太極先。外圓而內方,一坤與一乾。定體凝坤象,妙用周乾圜。壽年在其間,得之本自然。

3.3. The Prolonging Life through the Virtue of Yin

Heaven rewards good deeds and punishes evil deeds, and spirits reward goodness and punish evil. If one consciously does good deeds, aligning oneself with the Dao in tranquility and encountering blessings in action, then one’s life is in one’s own hands, not subject to the control of fate, and longevity and vitality are achieved without seeking them.天道福善禍淫,神明賞善罰惡逆。人能刻意為善,靜與道合,動與福會,如此則我命在我,不為司殺所執,不求壽而自壽,不求生而自生。

In cultivation, one should not be confined by wealth or poverty, nor should one exert undue effort. Instead, one should practice goodness in various situations, such as in dealing with fire and water, thieves and robbers, hunger and cold, illness and suffering, coercion and imprisonment, adversity and hardship, as well as in activities like flying, diving, moving, and planting. In all these situations, where there is effort, various forms of virtuous actions can accumulate limitlessly, and one will receive corresponding rewards.凡可修者,不以富貴貧賤拘,亦不在勉強其所為,但於水火,盜賊,饑寒,疾苦,刑獄逼迫,逆旅狼狽,險陰艱難,至於飛,潛,動,植,於力到處,種種多行方便,則陰德無限量,而受報如之矣。

In the past, a monk possessed six supernatural powers (shentong 神通) and dwelled in the wilderness with a novice monk. The monk knew that the novice monk would die in seven days, so he said: “Your parents missed you and wished for your temporary return. Come back in eight days.” The novice monk did return after eight days, which surprised the monk. Upon investigation, the novice monk on his way home shielded the anthill with his monk’s robe, allowing many ants to survive. As a result, the novice monk extended his lifespan by twelve years.昔比丘得六神通,與一沙彌同處林野間,比丘知沙彌七日當死,因曰:“父母思汝可暫歸,八日複來。”沙彌八日果來,比丘怪之入三昧。察其事,乃沙彌於歸路中脫袈裟壅水,令不得入蟻穴,得延壽一紀。

Sun Shu’ao 孫叔敖 (前630年–前593), when he was young, saw a two-headed snake and, fearing that others might also see it, killed and buried it. His mother said: “I had heard that those with yin virtue would be blessed by heaven, and you would not die.” Later, he became the Prime Minister of Chu (chulingyin 楚令尹).孫叔敖兒時見兩頭蛇,恐他人又見,殺而埋之,母曰:“吾聞有陰德者,天報之福,汝不死也。”後為楚令尹。

Dou Yujun 竇禹鈞 (?–?) dreamed one night that his grandfather told him: “You were getting older without children, and your lifespan was not long. You should cultivate yin virtue early”. Yujun diligently practiced the virtue of yin thereafter without fatigue. Later, he dreamed of his grandfather again, who said: “Due to your yin virtue, heaven had extended your lifespan by three decades, granted you five children, and bestowed honor and prestige, allowing you to reside in a celestial abode.”竇禹鈞夜夢祖父謂曰:“汝年過無子,又壽不永,當早修陰德。”禹鈞自是勤修陰德,行之罔倦。後又夢其祖父與曰:“天以汝陰德,故延壽三紀,賜五子,榮顯後,居洞天之位。”

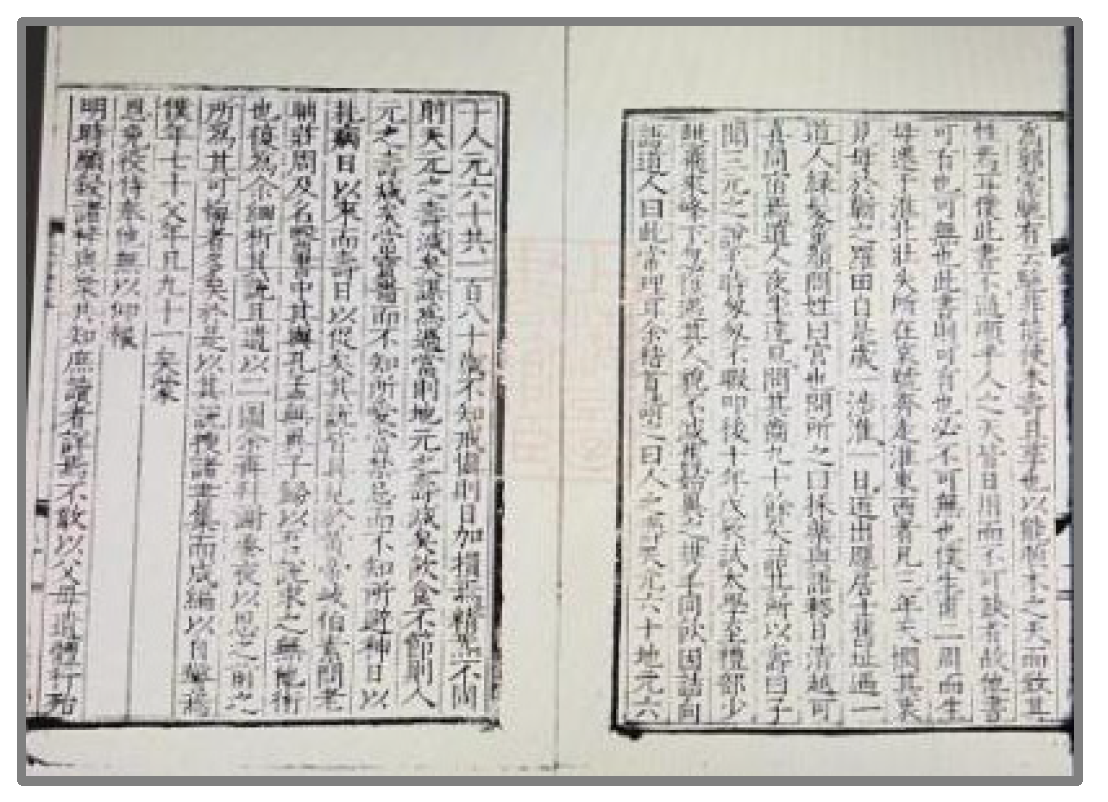

4. Multifarious Circulating Editions

4.1. The Yanshou Canzan System

4.2. The Canzan Yanshou System

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In addition to using the title Sanyuan Yanshou Canzan Shu when cataloging different versions and citing references, this paper consistently uses Sanyuan Canzan Yanshou Shu in discussions. |

| 2 | Three primes (sanyuan 三元), also translated into Three Origins. They refer to the Three Treasures, namely the Dao, the Scriptures and the Masters; Or the Three Officials, referring to the Heavenly Official, the Earthly Official and the Water Official; Or the Three Luminaries, that is, the Sun, the Moon and the Stars; or the Three Elixir Fields, namely, the Upper Elixir Field, the Middle EE Ar Field, the Lower Elixir Field; or the trinity of Essential Matter, Vital Pneuma and Spirit. |

| 3 | Research on Daoist health practices outside China originated in the late 19th century. Dr. Catherine Despeux of France studies Daoist internal alchemy for health preservation (Despeux 1979). Dr. Livia Kohn and Dr. Shoshin Sakade co-edited “Daoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques”, a collection of essays exploring Daoist meditation practices, featuring 11 contributions from prominent scholars in Japan, Europe, and the United States (Livia 1989). The anthology covers specific cultivation methods of various Daoist sects and Daoist philosophical perspectives. In Japan, Kando Honya specializes in the study of internal alchemy within the Quanzhen Dao during the Yuan dynasty (Kunio and Zhao 2007). |

| 4 | Research on this book began as early as the 20th century. Since then, scholars have continually advanced in this field, delving into the concepts and methods of health preservation. In 1998, An Peiguo 安培國 analyzed the sexual health preservation concepts and methods in the Sanyuan Yanshou Canzan Shu (An 1998, pp. 184–86). In 2006, Ge Jianmin 蓋建民 analyzed the Daoist three primes longevity health preservation concepts and their modern significance (Ge 2006, pp. 31–39). In the same year, Chen Qingyou 陳慶優 analyzed the textual structure and ideological sources of the Sanyuan Yanshou Canzan Shu (Chen 2006, pp. 6–42). In 2014, Wang Yi 王怡 analyzed the virtue cultivation methods in the Sanyuan Yanshou Canzan Shu (Wang 2014, pp. 8–9). In 2018, Chen Dongliang 陳東亮 and Chen Yang 陳陽 analyzed the Daoist health characteristics in the Sanyuan Yanshou Canzan Shu (Chen and Chen 2018, pp. 56–58). In 2022, Song Xin 宋鑫 and Jiang Weiyu 蔣維昱 explored the tri-element health preservation concepts in the Sanyuan Yanshou Canzan Shu (Song and Jiang 2022, pp. 1042–45). |

| 5 | The division standard for the 808 cited documents is as follows: Firstly, the Sanyuan Canzan Yanshou Shu is divided into 651 sections. This division is based on the Wanli edition of the Hu family’s Wenhuitang 文會堂, with reference to the results of Huang Yongfeng’s “Sanyuan Canshan Yanshou Shu” Quanzhu 詮注. Among them, volume three is divided based on the types of food, while the rest are divided based on the citation of “the book says”, or “someone says”, or by paragraph. Due to Li Pengfei’s consolidation and integration of some documents, they were decomposed according to Yangsheng Leizuan, adding 157 cited documents. |

| 6 | Mud Ball (niwan 泥丸), also translated into Muddy Pellet, a Daoist term relating to cultivation and asceticism. It refers to the central of the Nine Palaces in the head, namely, the upper elixir field. |

| 7 | The term “kuigang” (魁罡) is commonly employed in ancient astronomy and astrology, specifically referring to the leaders and chiefs within the Big Dipper constellation, believed to possess significant power and influence. |

| 8 | Semen Euryales (jitou 雞頭), also translated into gordon euryale seed or euryale seed, a Chinese drug. Dіstrіbution: Hunan, Jiangsu, Anhui and Shan dong Provinces of China. Properties sweet and puckery in flavor and neutral in nature. Meridian tropism: the Spleen and the Kidney Meridians. Action: to benefit the kidney and arrest seminal discharge; invigorate the function of the spleen and relieve diarrhea; and remove damp and check excessive leukorrhea. |

| 9 | Primordial Pneuma (yuanqi 元氣), also translated into fundamental life force. According to what is put in most Daoist scriptures, this formless chaos, transformed from great Dao, engenders yin and yang. As yin and yang interact with each other, all things on Earth come into being. |

| 10 | Gate of Life (mingmen 命門), a Daoist term relating to cultivation and asceticism, is another mame for the lower elixir field. |

| 11 | Mutual overcoming, also known as the inter-promotion among the Five Elements, refers to the transitional restraint or control that one element exerts over another it conquers. The sequence of mutual overcoming follows the same order as mutual conquest, namely wood overcomes earth, earth overcomes water, water overcomes fire, fire overcomes metal, and metal overcomes wood. Mutual insult refers to the reverse control, such as wood insulting metal (Xu 2019, p. 32). |

References

- An, Peiguo 安培國. 1998. Li Pengfi Sanyuan Canzan Yanshou Shu De Fangzhong Yangsheng Sixiang 李鵬飛《三元延壽參贊書》的房中養生思想. Qigong Zazhi 氣功雜誌 4: 184–186. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Dongliang 陳東亮, and Yang Chen 陳陽. 2018. Sanyuan Yanshou Canzan Shu Wenxian Kaocha Yu Yangsheng Tese 《三元延壽參贊書》文獻考察與養生特色. Zhongguo Zhongyiyao Tushu Qingbao Zazhi 中國中醫藥圖書情報雜誌 1: 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Guying 陳鼓應, and Jianwei Zhao 趙建偉. 2020. Zhouyi Jinzhu Jinyi 周易今注今譯. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Qingyou 陳慶優. 2006. Sanyuan Yanshou Canzan Shu Yangsheng Sixiang Yanjiu 《三元延壽參贊書》養生思想研究. Xiamen: Xiamen Daxue Shuoshi Xuewei Lunwen. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Yajun 程雅君. 2009. Zhongyi Zhexueshi (diyijuan) 中醫哲學史 (第1卷). Chengdu: Bashu Shushe. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Yajun 程雅君. 2010. Zhongyi Zhexueshi (di’erjuan) 中醫哲學史 (第2卷). Chengdu: Bashu Shushe. [Google Scholar]

- Despeux, Catherine. 1979. On Daoist Alchemy and Physiology. Paris: Les Deux Oceans Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Ru 高儒. 1957. Baichuan Shuzhi 百川書志. Shanghai: Gudian Wenxue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Xiu 高誘, Yuan Bi 畢沅, and Xiang Xu 餘翔. 1996. Lushi chunqiu 呂氏春秋. Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Hong 葛洪. 1988. Baopuzi Neipian 抱樸子內篇. Daozang(di ershiba ce) 道藏 (第28冊). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian. Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Jianming 蓋建民. 2001. Daojiao Yixue 道教醫學. Beijing: Zongjiao Wenhua Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Jianming 蓋建民. 2006. Shilun Daojiao Sanyuan Yanshou Yangsheng Sixiang Ji Xiandai Yiyi 試論道教“三元延壽”養生思想及其現代意義. Hunan Daxue Xuebao (Shehui Kexue Ban) 湖南大學學報(社會科學版) 4: 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Zhenyi 季振宜. 1985. Ji Cangwei Cangshumu 季滄葦藏書目. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Kunio, Hachiya 蜂屋邦夫, and Weigang Zhao 欽偉剛. 2007. Jindai daojiao yanjiu: Wang chongyang yu Ma danyang 金代道教研究:王重陽與馬丹陽. Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Pengfei 李鵬飛, and Yongfeng Huang 黃永鋒. 2021. Sanyuan Canzan Yanshou Shu Quanzhu 《三元參贊延壽書》詮注. Beijing: Zongjiao Wenhua Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Pengfei 李鵬飛. 1988. Sanyuan Yanshou Canzan Shu 三元延壽參贊書 Daozang(di shiba ce) 道藏 (第18冊). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian. Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Livia, Kohn. 1989. Daoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques, Center For Chinese Studies. Chicago: The University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Zhihua 彭智華. 2012. Zhongguo Chuantong Yide Yangsheng Guan Jiqi Xiandai Yiyi 中國傳統“以德養生”觀及其現代意義. Xue Lilun 學理論 2: 181–82. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Daxin 錢大昕. 1985. Bu Yuanshi Yiwenzhi 補元史藝文志. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Zhicheng 邱志誠. 2022. Zhou Shouzhong Jiqi Yangsheng Zalei Zaiyanjiu 周守忠及其《養生雜類》再研究. Zhongyiyao Wenhua 中醫藥文化 1: 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Xin 宋鑫, and Weiyu Jiang 蔣維昱. 2022. Li Pengfei Sanyuan Canzan Yanshou Shu Yangsheng Sixaing Tanxi 李鵬飛《三元參贊延壽書》養生思想探析. Zhongguo Zhongyi Jichu Yixue Zazhi 中國中醫基礎醫學雜誌 7: 1042–45. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Hongjing 陶弘景. 1988. Yangxing Yanming Lu 養性延命錄. Daozang(di shiba ce) 道藏 (第18冊). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. Shanghai: Shangshi Shudian. Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yi 王怡. 2014. Sanyuan Canzan Yanshou Shu Yangsheng Sixiang Tanxi 《三元參贊延壽書》養生思想探析. Yatai Chuantong Yiyao 亞太傳統醫藥 20: 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Mingshi 無名氏. 1995. Jujia Biyong Shilei Quanji 居家必用事類全集. Jinan: Qilu Shushe. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Xiaoying 許筱穎. 2019. Zhongyi Jichu Lilun 中醫基礎理論. Jinan: Shandong Keji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Zao 曾慥. 1988. Daoshu 道樞. Daozang(di ershi ce) 道藏 (第20冊). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. Shanghai: Shanghai Shudian. Tianjin: Tianjin Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Maoze 張茂澤. 2020. Zhongguo Sixiangshi Fangfalun Ji 中國思想史方法論集. Beijing: Guangming Ribao Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Shouzhong 周守忠, Feifei Xi 奚飛飛, and Xudong Wang 王旭東. 2018. Yangsheng Leizuan 養生類纂. Beijing: Zhongguo Zhongyiyao Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

| Number of Citations | Volume Head | Volume One | Volume Two | Volume Three | Volume Four | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Divided by Sanyuan Canzan Yanshou Shu | 5 | 76 | 226 | 318 | 26 | 651 |

| Further Refined According to Yangsheng Leizuan | 5 | 76 | 244 | 457 | 26 | 808 |

| Excerpted from Yangsheng Leizuan | 1 | 17 | 110 | 278 | 1 | 407 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, L.; Huang, Y. The Diverse Health Preservation Literature and Ideas in the Sanyuan Canzan Yanshou Shu. Religions 2024, 15, 834. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070834

Li L, Huang Y. The Diverse Health Preservation Literature and Ideas in the Sanyuan Canzan Yanshou Shu. Religions. 2024; 15(7):834. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070834

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Lu, and Yongfeng Huang. 2024. "The Diverse Health Preservation Literature and Ideas in the Sanyuan Canzan Yanshou Shu" Religions 15, no. 7: 834. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15070834