Building Episcopal Authority in Medieval Castile: The Bishops of the Diocese of Burgos (11th–13th Centuries)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

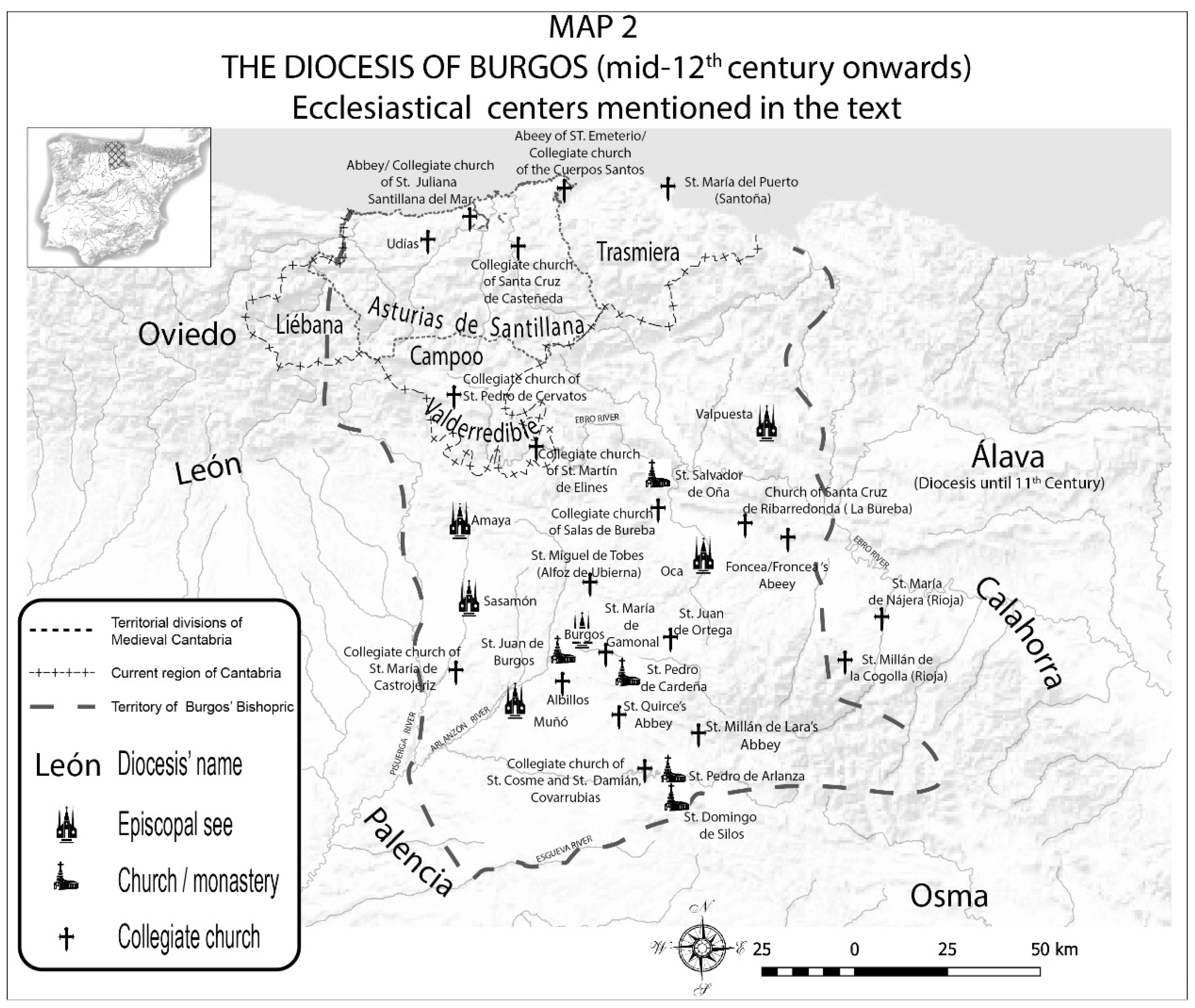

2. A Single Diocese Heading the Young Kingdom of Castile: Kings, Nobles, Abbots and Weak Bishops (10th–11th Centuries)

3. Episcopal Authority Challenged by the Large Monasteries and the Ambiguous Position of the Pontificate in the 12th Century

4. The Triumph of Episcopal Pre-Eminence and the Role of Bishop Maurice (1213–1238) as Architect of Great Agreements

4.1. The Bishop as Owner of Properties and Lordship Rights

4.2. The Jurisdictional Dimension of Episcopal Power: Hierarchical Superiority, Judge, Legislator and Title Holder of Ecclesiastic Rights

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For the diocese of Burgos until the 13th century, there are two classic studies (Serrano 1935—Mansilla Reoyo 1945). |

| 2 | Owing to limitations of space, we shall only mention some of the most important studies: on the churches of León’s Diocesis (López Quiroga 2005; Reglero de la Fuente 2018; Pérez 2020), on Galicia’s parishes (López Alsina 2009), on Vasque Country’s parishes (Curiel Yarza 2009) and on the Burgos’ Diocesis (Guijarro González and Díez Herrera 2022). Monasteries and churches have been also studied in relation to the building of territoriality in Medieval Western Spain prior to the Gregorian reform (Escalona Monge 2020). |

| 3 | The kingdom of Navarre reached its largest size during the reign of Sancho III the Great (1000–1035) when it ruled over the kingdom of León, the county of Castile and the modern provinces of Álava, Biscay and Guipúzcoa. On his death, he divided the kingdom between his sons and his son Ferdinand received the first two territories. On Ferdinand’s death (1065), his son Sancho inherited the county of Castile and called himself king (Sancho II of Castile, 1065–1072). |

| 4 | They shared boundaries with the Kingdom of Pamplona (Navarre from the 11th century), which had promoted the bishopric of Calahorra, from its domination over the lands of La Rioja until the mid-11th century, and absorbed the episcopal sees of Álava (which was supressed), Valpuesta and Oca. However, the military victory of Ferdinand I, king of León and Count of Castile, over the king of Navarre, García Sánchez III, in 1054 returned the sees of Valpuesta and Oca to the kingdom of Castile. |

| 5 | (Garrido 1983a), 13, no. 11 (April 1024) and (Fernández Flórez and Serna Serna 2017), Becerro Gótico de Cardeña, no. 63 June 2019. |

| 6 | (Garrido 1983a), 13, no. 24 (July 1074) and no. 26 (1075). |

| 7 | (Garrido 1983a), 13, no. 45 (December 1088). In 1088, three brothers entered with their properties in the family monastery of San Miguel de Tobes (alfoz de Ubierna) and swore to live under obedience to the bishop. With this oath, it can be inferred that perhaps the monastery was under the patronage of Bishop Gómez II. (Garrido 1983a), 13, no. 53 (1094). In 1094 he received property in Anaya Gustios (from a countess) and from Doña Mayor (grand-daughter of Count Rodrigo González de Lara) in three towns in the regions of Ubierna and Poza. (Garrido 1983a), 13, no. 59 (February 1096). With the consent of the chapter, Bishop Gómez changed them with two landowners in the alfoz de Villadiego. |

| 8 | (Garrido 1983a), 13, no. 36 (February 1078). |

| 9 | (Garrido 1983a), 13, no. 44 (November 1087). |

| 10 | (Garrido 1983a), 13, no. 67 (December 1099) (Fernández Flórez and Serna Serna 2017), Becerro Gótico de Cardeña, no. 168 (October 1045). |

| 11 | (Serrano 1930, ) no. 216 (1086). |

| 12 | (Garrido 1983a), 13, no. 67 (December 1099). (Jusué 1912, no. 61 (1031) and (Garrido 1983a) 13, no. 50 (April 1093): exemption of thirds and census. |

| 13 | (Garrido 1983a), 13, no. 66 (April 1099): Urban II confirmed and enlarged the privileges of the bishop of Burgos. |

| 14 | (Garrido 1983a), 13, no. 129 (April 1144): Pope Lucius III. |

| 15 | (Garrido 1983a), 13, no. 138 (June 1152): Pope Eugene III ordered Bishop Victor and the abbot of Oña to meet and reach an agreement as regards their dispute over the payment of tithes. Garrido, 13, no. 139 (03/09/1152): Pope Eugene II urged the abbot of Oña to fulfil the agreements reached or he would take measures against him. |

| 16 | |

| 17 | (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 353 (March 1201): Bull of Innocent III. |

| 18 | (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 355 (March 1201), no. 356 (March 1201) and no. 358 (March 1201): Letters from Innocent III. |

| 19 | (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 425 (April 1210), no. 426 (April 1210) and no. 427 (April 1210): Innocent III. |

| 20 | (Oceja Gonzalo, 1983) no. 107 (1209–1210). |

| 21 | (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 339 (May 1199): Innocent III confirmed the previous concord (1163) between the monastery of San Millán and the bishop of Burgos. |

| 22 | (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 163 (July 1162–1165): Bull of Alexander III. |

| 23 | (Peña Pérez 1983), no. 46 (July 1185) and no. 56 (1194). |

| 24 | (Garrido 1983a), 13, no. 19 (March 1068): King Sancho II restores and endows the episcopal see of Oca. Garrido, 14, no. 267 (04/12/1186): King Alfonso VIII exchanged with Bishop Marino the collegial church of Cervatos for the monastery of Santa Eufemia de Cozuelos. |

| 25 | (Garrido 1983a), 13, no. 148 (October 1157). |

| 26 | (Garrido 1983a), 13, no. 75 (March 1168): Bishop Pedro granted a charter (lands to be used and exemption of taxes) to the inhabitants of the town of Madrigal del Monte. (Garrido 1983b), 14, I, no. 227 (March 1185) and no. 253 (25/08/1184): purchases by Bishop Marino in Valedetobes. Concessions in preaestimonium (Guijarro González 2020, pp. 37–38). |

| 27 | (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 276 (January 1188) and Garrido 1983a, no. 190 (April 1174). |

| 28 | There is a brief and early monograph about Bishop Mauricio (Serrano 1922). |

| 29 | (Cathedral Archive of Burgos, May 1243, vol. 33, fol. 86). |

| 30 | In the Archive of Burgos Cathedral, some account books from the 13th century (1266–1287), the 14th century (1355–1398) and the 15th century are preserved, which record the places where the bishop received income from the tithe. Although not all of the books from each century have been preserved, it can be seen that a large number of these places appear in the inventory of 1515. To this must be added the information on these places provided by non-serialised sources in the archive. All of this has allowed the scholar (Pereda Llarena 1986), who has previously studied this inventory, to establish the hypothesis that the situation it reflects in relation to the places where the part of the tithe belonging to the bishop was collected is quite close to what happened at the beginning of the 16th century. |

| 31 | (Pereda Llarena 1986, pp. 521–27). The inventory can be found in his unpublished graduate dissertation. |

| 32 | (Pereda Llarena 1986, pp. 528–36). These places were recorded in a list during the Thirteenth century. |

| 33 | (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 480 (June 1214): Innocent III recommended that the bishops of Osma and Burgos should send representatives to the Fourth Lateran Council to document the boundaries between the two dioceses. (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 491 (March 1216). |

| 34 | (Garrido 1983b, 14, no. 354 (25 March 1201). |

| 35 | (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 352 (20 March 1201): He ordered abbot Arlanza to respect the right of Bishop Mateo to receive tithes from the church of Villaverde and nominate its clergy. |

| 36 | (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 355 (28 March 1201). |

| 37 | (Garrido 1983b),14, no. 425 (April 1210). |

| 38 | (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 515 (May 1218): Concord between Bishop Maurice and San Salvador de Oña, pp. 399–400. |

| 39 | Cathedral Archive of Burgos, 1236, vol. 25, fol. 348. |

| 40 | (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 537 (January 1222): The churches of San Pelayo and San Pedro in the town of Santo Domingo de Silos and the monasteries of San Millán de Lara and Los Perros. |

| 41 | (Férotin 1897), no. 82 and no. 85 (1213). |

| 42 | (Vivancos Gómez 1988), no. 89 (January 1216). |

| 43 | (Vivancos Gómez 1988), no. 95 (November, 1218): Bishop Mauricio visited the monastery. And no. 98 (December 1219): Bull of Honorius III. |

| 44 | (Vivancos Gómez 1988), no. 97 (August 1219): Ordinances of the King Fernando III. |

| 45 | (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 525 (November 1221): Honorius III: no. 527 (18/01/1221): episcopal administration of the churches of Castrojeriz; (Garrido 1983b), no. 544 (October 1222): Constitutions of Bishop Maurice addressed to the clergy in the collegial church of Castrojeriz. |

| 46 | (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 542 (July 1222). |

| 47 | (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 541 (June 1222). |

| 48 | (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 511 (September 1217). |

| 49 | (Garrido 1983b), 14, no. 484 (November 1214): Monasteries of San Juan de Ordejón and San Juan de Mena. |

| 50 | Cathedral Archives of Burgos, November 1230, vol. 17, fol. 525: “Concordia Mauriciana”. |

References

- Carbajal Castro, Álvaro, and Josu Narbarte Hernández. 2019. Royal power and proprietary churches in the eleventh-century Kingdom of Pamplona. Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies 22: 115–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel Yarza, Iosu. 2009. La parroquia en el País Vasco-Cantábrico durante la Baja Edad Media (1350–1530): Organización eclesiástica, poder señorial, territorio y sociedad. Vitoria: Editorial de la Universidad del País Vasco. [Google Scholar]

- Dorronzoro Ramírez, Pablo. 2013. La creación de la diócesis de Burgos en el siglo XI. Una nueva perspectiva. Estudios medievales hispánicos 2: 47–87. [Google Scholar]

- Escalona Monge, Julio. 2020. Organización eclesiástica y territorialidad en Castilla antes de la reforma gregoriana. In La construcción de la territorialidad en la Alta Edad Media. Edited by Iñaki Martín Viso. Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca, pp. 167–201. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Flórez, José Antonio, and Sonia Serna Serna. 2017. El Becerro Gótico de Cardeña. El primer gran cartulario hispánico (1086). Vol. II Documentos e Índices. Burgos: Real Academia de la Historia-Instituto castellano-leonés de la Lengua. [Google Scholar]

- Férotin, Marius. 1897. Récuil des Chartes de l’Abbaye de Silos. Paris: Imprimerie Nationales, 2nd ed. 2018, Paris: Forgotten Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fita, Fidel. 1894. Bulas inéditas de Urbano II. Ilustraciones al concilio nacional de Palencia (5–8 Diciembre 1100). Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia 24: 547–53. [Google Scholar]

- Fita, Fidel. 1906. El concilio nacional de Burgos, 1117. Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia 48: 387–407. [Google Scholar]

- García de Cortázar, José Ángel. 2018. La construcción de la diócesis de Calahorra en los siglos X al XIII: La Iglesia en la organización social del espacio. Logroño: Instituto de Estudios Riojanos. [Google Scholar]

- García y García, Antonio. 2000. Concilios y sínodos en el ordenamiento jurídico de del reino de León. In Iglesia, Sociedad y Derecho. Salamanca: Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca, pp. 9–146. [Google Scholar]

- García y García, Antonio, ed. 1997. Synodicon Hispanum, Burgos y Palencia. Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos, vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, José Manuel. 1983a. Documentación de la Catedral de Burgos (804–1183). Fuentes castellano-leonesas 13. Burgos: Ediciones J. M. Garrido. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, José Manuel. 1983b. Documentación de la Catedral de Burgos (1184–1222). Fuentes castellano-leonesas 14. Burgos: Ediciones J. M. Garrido. [Google Scholar]

- Guijarro González, Susana, and Carmen Díez Herrera. 2022. La construcción de la parroquia medieval en la diócesis de Burgos: Cantabria entre los siglos IX al XV. Madrid: Sílex. [Google Scholar]

- Guijarro González, Susana. 2020. Obispos y laicos durante el período de génesis y afirmación de la diócesis de Burgos (siglo XI-XII). Revista de historia Jerónimo Zurita 97: 15–43. [Google Scholar]

- Huidobro y Serna, Luciano. 1952–1953. Señoríos de los prelados burgenses: Fortalezas y palacios a ellos anejos. Boletín de la Institución Fernán González 31: 295–306, 32: 391–401. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10259.4/1104 (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Jusué, Eduardo. 1912. Libro de la Regla o Cartulario de la Antigua abadía de Santillana. Madrid: Sucesores de Hernando. [Google Scholar]

- López Alsina, Fernando. 2009. Da protoparroquia ou parroquia antiga altomedieval á parroquia clásica en Galicia. In A Parroquia en Galicia: Pasado, presente e futuro. Edited by Fernando Pazos García. Santiago: Xunta de Galicia, pp. 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- López Quiroga, Jorge. 2005. Los orígenes de la parroquia rural en el occidente de Hispania (siglos IV-IX) (provincias de Gallaecia y Lusitania. In Actes du colloque international, Aux origines de la paroisse rurale en Gaule méridionale (IVe-IXe siècles). Edited by Christine Delaplace. París: Salle Tolosa, pp. 193–228. [Google Scholar]

- Lunven, Anne. 2014. Du diocèse à la paroisse. Éveches de Rennes, Dol et Alet/ Saint Malo (Ve-XIIIe siècle). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. [Google Scholar]

- Mansilla Reoyo, Demetrio. 1945. Iglesia castellano-leonesa y curia romana en los tiempos del rey San Fernando: Estudio documental sacado de los registros vaticano. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Díez, Gonzalo. 2004. Desde la invasión musulmana al traslado de la sede de Oca a Burgos: 781–1081. In Historia de las diócesis españolas. Iglesias de Burgos, Osma-Soria y Santander. Edited by Bernabé Bartolomé Martínez. Madrid: BAC, chap. II. vol. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Mazel, Florian. 2016. L’évêque et le territoire: L’invention médiévale de l’espace. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Oceja Gonzalo, Isabel. 1983. Documentación del monasterio de San Salvador de Oña (1032–1284). Fuentes castellano-leonesas. Burgos: Imprenta J. M. Garrido, pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, John S. 2015. Bishops, Authority and Community in Northwestern Europe, c.1050–1150. Cambridge and New York: University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Peña Pérez, Francisco J. 1983. Documentación del monasterio de San Juan de Burgos (1091–1400). Fuentes castellano-leonesas 1. Burgos: Imprenta J. M. Garrido. [Google Scholar]

- Pereda Llarena, Francisco Javier. 1986. Aproximación al estudio del señorío eclesiástico y de la capacitación decimal de la sede epsicopal burgalesa (Siglos XI-XIII). Unpublished Postgraduate dissertation, Universidad de Valladolid-Colegio Universitario de Burgos, Burgos, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, Mariel. 2020. Monasterios, iglesias locales y articulación religiosa de la diócesis de León en la Alta Edad Media. In Obispos y monasterios en la Edad Media: Trayectorias personales, organización eclesiástica y dinámicas materiales. Edited by Andrea Vanina Neyra and Mariel Pérez. Buenos Aires: Sociedad Argentina de Estudios Medievales, pp. 95–124. [Google Scholar]

- Peribáñez Otero, J. 2023. Consolidación y coflictividad en la diócesis de Osma. In Construcción del espacio diocesano en la Europa medieval: Actores, dinámicas y conflictos. Edited by Susana Guijarro, Leticia Agúndez San Miguel and Iván García Izquierdo. Madrid: Sílex, pp. 149–69. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, David N. 2023. La consolidación de la frontera oriental de la diócesis burgalesa, 1150–1250. Hispania sacra 75: 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reglero de la Fuente, Carlos. 2018. “Ecclesiae” y “monasteria” en la documentación latina de León: Un paisaje monumental. In Las palabras del paisaje y el paisaje en las palabras de la Edad Media: Estudios de lexicografía estudios de lexicografía latina medieval hispana. Edited by Estrella Pérez Rodríguez. Bélgica: Brepols Publishers NV, Corpus Christianorvm. Lingua Patrum, vol. 11, pp. 339–369. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Domingo, Rafael. 2016. La exención de jurisdicción episcopal en los monasterios benedictinos de Castilla. Revista de la Inquisición. Intolerancia y derecho humanos 12: 153–74. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, Luciano. 1922. Don Mauricio, Obispo de Burgos y fundador de su catedral. Madrid: Juan de Ampliación de Estudios e Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, Luciano. 1930. Cartulario de San Millán de la Cogolla. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Históricos. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, Luciano. 1935. El Obispado de Burgos y la Castilla primitiva. Desde el siglo V hasta el siglo XIII. Madrid: Instituto de Valencia de Don Juan. [Google Scholar]

- Vivancos Gómez, Miguel C. 1988. Documentacion del monastério de Santo Domingo de Silos. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Susan. 2013. The Proprietary Church in the Medieval Wes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zadora-Rio, Elisabeth. 2008. Introduction. In Des paroisses de Toureine aux comunes d’Indre-et-Loire. La formation des territories. In 34e Supplément à la revue Archéologique du Centre de France. Tours: Université de Tours, CNRS, pp. 10–16. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guijarro, S. Building Episcopal Authority in Medieval Castile: The Bishops of the Diocese of Burgos (11th–13th Centuries). Religions 2024, 15, 1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091074

Guijarro S. Building Episcopal Authority in Medieval Castile: The Bishops of the Diocese of Burgos (11th–13th Centuries). Religions. 2024; 15(9):1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091074

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuijarro, Susana. 2024. "Building Episcopal Authority in Medieval Castile: The Bishops of the Diocese of Burgos (11th–13th Centuries)" Religions 15, no. 9: 1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091074

APA StyleGuijarro, S. (2024). Building Episcopal Authority in Medieval Castile: The Bishops of the Diocese of Burgos (11th–13th Centuries). Religions, 15(9), 1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel15091074