Abstract

This article presents an introductory historical, sociolinguistic, and ethnographic study of “Wazobia gospel music”, a twenty-first-century Nigerian congregational musical genre. The term ‘Wazobia’ signifies a fusion of the three regionally recognized local languages in Nigeria: Wa (Yorùbá), Zo (Hausa), and Bia (Igbo)—words that mean ‘come’ in the respective languages. In the Nigerian context, the Wazobia concept could also symbolize the inclusion of more than one ethnicity or language. By dissecting three multilingual Nigerian congregational songs, I unveil the diverse perceptions of Wazobia gospel music and the associations of the musical genre in line with the influencing agencies, text, and performance practices. Furthermore, I provide a detailed description and analysis of the textual and sonic contents of Wazobia gospel music, emphasizing its roles, meanings, and functions in the Lagos congregations context. I argue that Wazobia gospel music—multilingual singing in Nigerian churches—embodies multilayered roles in negotiating identity and creating hospitality. The complexity of studying congregational singing in cosmopolitan cities (like Lagos, Nigeria) due to multiple ethnolinguistic and musical expressions within local and transnational links is also addressed. To tackle this complexity, this article adopts an interdisciplinary approach, combining historical research, oral history, and hybrid ethnography. This approach ensures a thorough and in-depth understanding of Wazobia gospel music, a topic of significant importance in the study of Nigerian music, linguistics, and cultural studies. By employing frameworks of musical localization and signification, I incorporate the results of my ethnographic studies of three Protestant churches in Lagos, Nigeria, to illustrate Wazobia gospel music’s continued importance. The article conceptualizes multilingual singing and offers fresh perspectives on studying Nigerian Christian congregational music in the twenty-first century.

1. Introduction

Music is profoundly significant across cultures and societies. It may serve as a unifying language that transcends linguistic barriers, enabling people from diverse backgrounds to connect emotionally and culturally. Music can evoke powerful emotions, convey deep messages, and foster a sense of community and belonging. In various cultures, music plays a crucial role in rituals, celebrations, and daily life, providing a means for expression and communication. In the Nigerian context, just like many other multilingual societies, music is an integral part of cultural heritage, with contemporary genres like Afrobeat, Highlife, Juju, and Gospel music reflecting the nation’s rich history and diversity.1 Nigerian music has gained global recognition, showcasing the country’s artistic talents and contributing to its cultural diplomacy.

As a result of globalization, Nigeria is increasingly important in world music, economics, and religion.2 Nigeria is essential to global Christianity because of the large number of Christians within the country and the influence of its diaspora. For example, Evanthia Patsiaoura’s work about the Nigerian diaspora in Athens, Greece, underscores how “Nigerian Pentecostals employ music to express, facilitate, and embody faith in the church and everyday life settings” (Patsiaoura 2018, p. 167). Through what Patsiaoura calls “shared musico-spiritual practice” in Athens’ locality, she describes what may inform how Nigerian Pentecostal congregations across geographic borders are shaped, experienced, and imagined” (Patsiaoura 2018, p. 177). The diaspora study exemplifies how Christians in Nigeria listen to and worship through gospel music. As African scholar Ezra Chitando points out, “Gospel music represents a valuable entry point into a discussion of contemporary African cultural production” (Chitando 2002, p. 5). Studying Nigerian gospel music may provide an entry to understanding more significant Nigerian cultures. Therefore, scholars must delve into the intricacies of Nigerian gospel music, as this is a key to unlocking the beliefs and practices of this large and influential group of Christians. This article aims to describe multilingual singing in selected Lagos Christian congregational worship and examine its various roles, meanings, and functions in negotiating identities and creating hospitality. In addition, the article seeks to identify how multiethnic churches may reflect on the concept of multilingual singing and its implications on congregational worship.

The article employs historical, sociolinguistic, and ethnographic approaches to examine “Wazobia gospel music”, a term the author coined to conceptualize multilingual singing in Lagos, Nigeria. Wazobia gospel music may exemplify a subgenre of Nigerian gospel music in multiethnic and multicultural congregations. Providing an introductory view of Nigerian gospel music is essential before considering the intricacies of Wazobia gospel music.

2. Nigerian Gospel Music: A Cursory Background

Like many other evolving concepts, gospel music in Nigeria has received different interrogations and interpretations by musicians, patrons, and scholars, emphasizing various aspects such as its origin, functions, and content. While scholars have argued for or against the fact that Nigerian gospel music started before the 1960s, there is general agreement that some significant developments began during this pivotal decade. Nigerian theologian and sacred musicologist Femi Adedeji traces the origin of Nigerian gospel music to the 1960s and argues that this development had its antecedent thirty years earlier (Adedeji 2005, p. 146). Various names attached to Nigerian gospel music were orin ìgbàgbo (Christian songs), gospel, indigenous sacred songs, and spiritual songs.3 Definitions of gospel music in Nigeria have emphasized its two-pronged nature as a spiritual and social commodity, exhibited in its use in the church setting and outside the church (Adeola 2021, p. 85). This understanding suggests that gospel music in Nigeria is not restricted to the formal Christian liturgy as a branch of Christian music but is also adaptable to Christian activities outside the strict liturgical settings, such as social functions.

Nigerian gospel music shares some similarities and distinctiveness with African American gospel in its performance practices. One of the foremost researchers in Nigerian gospel music, Matthew Ojo, observes that Nigerian gospel music is similar to African American gospel music in its audience participation, the repetitiveness of its song verses, constant improvisation, and the pattern of its calls and responses, among other features (Ojo 1998, p. 211). However, Nigerian gospel music is distinctive in its use of indigenous drums, such as sèkèrè, dùndún, and agogo, which are often mixed with Western instruments, such as drum sets, keyboards, and synthesizers (Ojo 1998, p. 216). Gospel music is gaining large audiences throughout Nigeria because the musicians try to express their messages cross-culturally as they engage in cultural and ethnic diversities, making constructing a global identity a viable enterprise (Ojo 1998, p. 230). It is, therefore, pertinent to consider briefly how language diversities may have contributed to music multilingualism in Nigeria.

3. Understanding Ethnolinguistic Composition

In order to understand the dynamics of Nigerian gospel music, it is first important to understand the degree of linguistic complexity in Nigeria. With about 500 native languages, Nigeria is one of the most linguistically diverse countries in the world (Nwafor 2002, p. 22). The ethnolinguistic diversity in Nigeria was a significant factor that necessitated the adoption of English as the official language of communication.4 Residents in cosmopolitan cities also devised new means of communication using the most common vernacular languages and Nigerian Pidgin to carve a unique ethnolinguistic identity. Scholars have discussed the creative appropriation of various Nigerian languages (including Nigerian pidgin) in performing popular and gospel music (Liadi 2012; Adedeji 2010). Nigerian Pidgin5 is developing as a major lingua franca in multilingual workplaces, schools, and most cosmopolitan cities. Nigerian Pidgin is intelligible to both uneducated and educated people.

The multilinguistic conditioning in Nigeria is complex. Most Nigerian historians concur that the country has more than 250 ethnic groups (Falola and Heaton 2008; Mwakikagile 2002; Nwafor 2002). The linguistic situation in Nigeria is such that major and minor languages are classified according to their speakers’ population and perceived widespread use (Oyetade 1992, p. 33). For example, minority languages, such as Edo, Efik, Fulfulde, Izon, Kanuri, and Tiv, are spoken by smaller ethnolinguistic groups scattered throughout the country. After the initial creation of the twelve states of the Federation, these languages were included in the national news broadcast (Tomori 1985, p. 287). Nigerian linguist Oluwole Oyetade supports the view that the three major languages―Yorùbá, Hausa, and Igbo―are widely spoken outside their states of origin, and “these main languages together with the others in the group are often used officially at the national level for news broadcast on Radio Nigeria” (Oyetade 1992, p. 33). Therefore, the three major languages collectively representing Wazobia–Hausa, Igbo, and Yorùbá could be regarded as languages of wider communication in Nigeria besides English.

In the Nigerian context, the term “Wazobia” represents a confluence of the three regionally recognized local languages: Wa (Yorùbá), Zo (Hausa), and Bia (Igbo)―terms which mean ‘come’ in the three languages. In places or settlements where there are Nigerians, Wazobia could also symbolize the inclusion of more than one ethnicity or language.

The Wazobia idea is ubiquitous beyond the academic space. The media and market space also embody the Wazobia—multilingual concept. Wazobia radio and television, featuring a mixture of native languages and Nigerian Pidgin, provide platforms for mediating indigenous songs and local news across cosmopolitan cities in Nigeria.6 The Wazobia concept has transcended Nigeria’s borders. For example, Wazobia African markets are available in Houston, Texas, where people can shop for Nigerian groceries and other locally-made products.7 Wazobia has become a local and international concept.

This article extends the multilingual, multicultural ideal expressed in the term “Wazobia” beyond the marketplace to the realm of Christian congregational music. To do so, I explore the intersections of multiple languages within Nigerian Christian congregational music, focusing on selected churches in Lagos, a cosmopolitan city in Nigeria. The purpose of the study is to uncover issues this cultural–religious relationship engenders. The practice of Christian congregational music in Lagos embodies the merging of multiethnic groups, cosmopolitanism, and the flow of transnational activities. Within the framework of this study, musical worship in Protestant churches is usually bilingual, multilingual, or multiethnic, structured to reflect diversity and inclusion. As a result, aspects of congregational music (the use of repertoire, such as hymns, choruses, contemporary songs, and indigenous instruments) are often selected to mirror the multiple ethnic or tribal identities of the parishioners. I use the term “Wazobia gospel music” to describe the contemporary multilingual congregational music repertoire often used in the Nigerian context to bridge cultural and linguistic divides.

4. Methodology and Theoretical Framework

This article is a product of my dissertation ethnographic study. My primary methodologies included participant observation, semi-structured interviews, and congregational surveys. As a native of Nigeria and a student of Yorùbá culture, I engage my background understanding of the culture in reviewing both old and current literature to situate relevant developments of local musical expression. Ethnography is a viable method for describing the observed interface of music and culture (Rice 2014, p. 34). Therefore, I have employed participant/observer ethnographic research methods, incorporating interviews, online surveys, and congregational music from three Protestant churches in Lagos. My motivation for studying the three congregations has developed over the last decade as a “cultural insider” and “culture bearer” of Wazobia gospel music.8 My extensive experience in the field, serving on staff at one of the churches since 2015 and attending several services and musical concerts at the other two churches over the last twenty years, provides a solid foundation for this study. The three churches’ geographical location (two on Lagos Island and one on Lagos Mainland) and demographics (including parishioners’ language diversity) are helpful for investigating music and multilingualism. In addition, the three churches have developed a sophisticated digital audiovisual ministry that enabled me to conduct “hybrid ethnography”, integrating in-person observations with a view of online services.9 From November 2023 to January 2024, I visited the three churches’ Sunday services, midweek services, and music rehearsals. I conducted semi-structured interviews with five members and worship leaders from each church.10 After my in-person participant observation in January 2024, I continued to study the three congregations incorporating hybrid ethnography through online and offline platforms (Przybylski 2020, p. 3) until April 2024.

My fieldwork incorporates both ‘emic’ and ‘etic’ perspectives. This approach is rooted in my background as a polyglot who can speak three local languages (Yorùbá, Hausa, and Nigerian Pidgin) and English. I consider myself an insider, which gives me significant access to the history of the growth and development of the Nigerian congregational song repertory. As a practitioner, I have led congregations in singing multilingual songs. The “emic” perspective within my home congregation seemed insufficient for studying the complexity of music and language in Lagos congregational singing. Therefore, I sought to conduct research as an “outsider” among other Lagos-based congregations that are part of different denominations. However, since I am a practicing Christian from Nigeria, speaking multiple local languages, I see myself more or less completely as an insider within Nigerian diverse cultures. The typical critiques of emic perspectives have raised concerns that the researcher is so close to the phenomenon that they lack a critical perspective (Nettl 1992, p. 387). My research has considered both the “emic” and “etic” perspectives. It uses varied academic theories and methods to give a more distanced perspective on studying Wazobia gospel music. Furthermore, the “etic” academic audience of my postgraduate research in the UK and my doctoral work in the United States has helped to refine my perspective.

The article interprets this research in light of two main theories: “signification” and “musical localization”. As an essential aspect of musical understanding, Akin Euba proposes that signification may assist in establishing the identity and meaning of local music (Euba 2001, p. 121). This theory alludes to musical instruments as signifiers that enable us to recognize musical types, although we can also understand musical types through an assortment of signifiers. According to Euba, texts appear to be a significant signifier in Africa, which explains why texts are used in vocal and instrumental music.

The second framework, “musical localization”, conceptualizes the role of congregational music in local communities. This model discusses how local people make congregational music and what specific identity local music-making reveals about the people, the cultures, or surrounding influences. Musical localization is defined as:

The process by which Christian communities take a variety of musical practices―some considered ‘indigenous’, some ‘foreign’, some shared across spatial or cultural divides; some linked to past practice, some innovative―and make them locally meaningful and useful in the construction of Christian beliefs, theology, practice, or identity.(Ingalls et al. 2018, p. 30)

In this study, musical localization explains how Nigerian gospel music has evolved amidst various influences, such as traditionalism, multiculturalism, and transnationalism. In other words, recently, the performance practice of Wazobia gospel music draws mainly from a fusion of indigenous musical elements, ethnolinguistic diversity, and foreign influences.

Wazobia gospel music study fills a gap in the emerging research of Nigerian contemporary Christian music. Limited academic literature explores studies of Christian congregational music and multilingualism in Nigeria. Many available scholarly investigations focus solely on the social collectivity of music in monolingual contexts and mass-mediated Nigerian gospel music.11 While providing valuable insights into the contexts of Nigerian gospel music, prior studies neglect a careful investigation of the current upsurge of multilingual congregational song repertoires directly linked with the Nigerian evangelical churches and gospel music industry. This study is an attempt to fill this lacuna.

5. Explanation of Field Data and Sources

Since not much study has been conducted on contemporary Nigerian gospel music, particularly from a linguistic perspective, any undertaking in this area appears immensely difficult. The current study gathers empirical data from Protestant churches, mainly Baptists and Pentecostals, to conceptualize the reception of Nigerian contemporary gospel music. In order to galvanize a broader representation, I extended my online survey beyond the three field sites to other Protestant churches in Lagos. Between November 2023 and March 2024, I received 161 responses from fifteen churches.12 These churches represent congregations in Lagos, where Wazobia gospel music is regularly performed in worship/services and other Christian musical events.

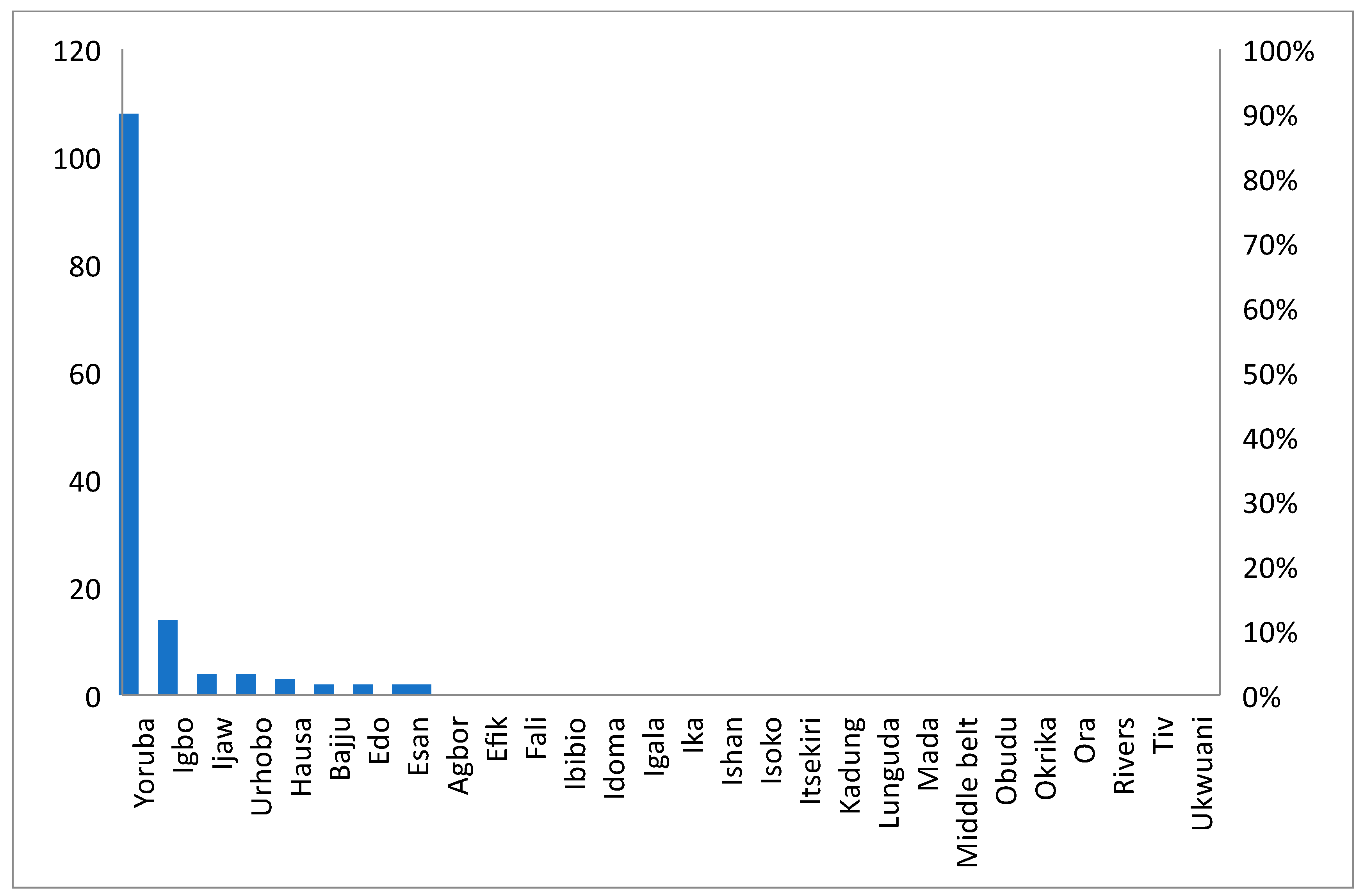

The data reveal the language distribution in Lagos Protestant churches. Participants in the online survey were from different languages and ethnicities. Figure 1 below indicates demographic data by ethnicity. The graph shows that participants from twenty-eight ethnicities participated in the survey, with Yorùbá, Igbo, Ijaw, Urhobo, and Hausa in the top five. The number of participants according to the languages of the top five is Yorùbá (108), Igbo (14), Ijaw (4), Urhobo (4), and Hausa (3). In addition to revealing the diversity of cultures represented in the Christian religious setting, this data reflects the socio-ethnolinguistic and economic makeup of the inhabitants of Lagos. Although Ile-Ife in Osun State, Nigeria, is widely known as the ancestral home of the Yorùbá people, in recent decades, Lagos, located in the southwest, has become the most prominent city of Yorùbá speakers. However, many Igbo and Hausa have historically settled in Lagos on economic grounds (Animashaun 2020, p. 62). My data explain why congregants from some ethnicities make up a higher percentage and suggests why songs from specific languages feature more frequently in congregational singing than others. For example, in the monolingual song category of all the churches I visited, Yorùbá songs appear more regularly in congregational singing than in other languages. However, Yorùbá songs fuse with songs from different languages in the multilingual category.

Figure 1.

Demographics of worshippers by ethnicity.13

The survey data also reveal styles of congregational worship in the churches. In this regard, Nigerians share several Christian worship practices worldwide, past and present. Liturgical theologian Ruth Duck has called attention that “honoring Christians of all nations and cultures means exploring the great variety of ways Christians worship in the world” (Duck 2013, p. 6). This idea points to the uniqueness of how different traditions describe Christian worship. Duck suggests further how to approach congregational worship study.

Another way to understand Christian worship’s diversity is through congregational and ethnographic studies, by spending significant time worshiping with a particular congregation and conversing with the leaders and members. In this way, researchers learn what worship means to the congregation members beyond descriptions in worship books, denominational guidelines, and scholarly reflections. Of course, researchers must focus on careful listening and realize the limits of what they can learn in a relatively brief sojourn with the congregation (Duck 2013, p. 6). Knowing the nuances various congregations use in their worship is necessary for describing their congregational music practices.

Issues related to worship styles have preoccupied discussions of Christianity in various traditions. According to Constance Cherry, “Worship styles will always be a part of the landscape for Christian worship. So, worship architects need to understand the role that style plays, and they need a vocabulary that helps them be conversant about it as they lead”.14 Cherry identifies and discusses five worship styles within Western Christianity: liturgical, traditional, contemporary, blended, and alternative (ancient-future worship and seeker services), and suggests a “convergence worship” model (Cherry 2021, pp. 254–61). I found Duck’s concept and Cherry’s models helpful in describing Nigerian worship styles.

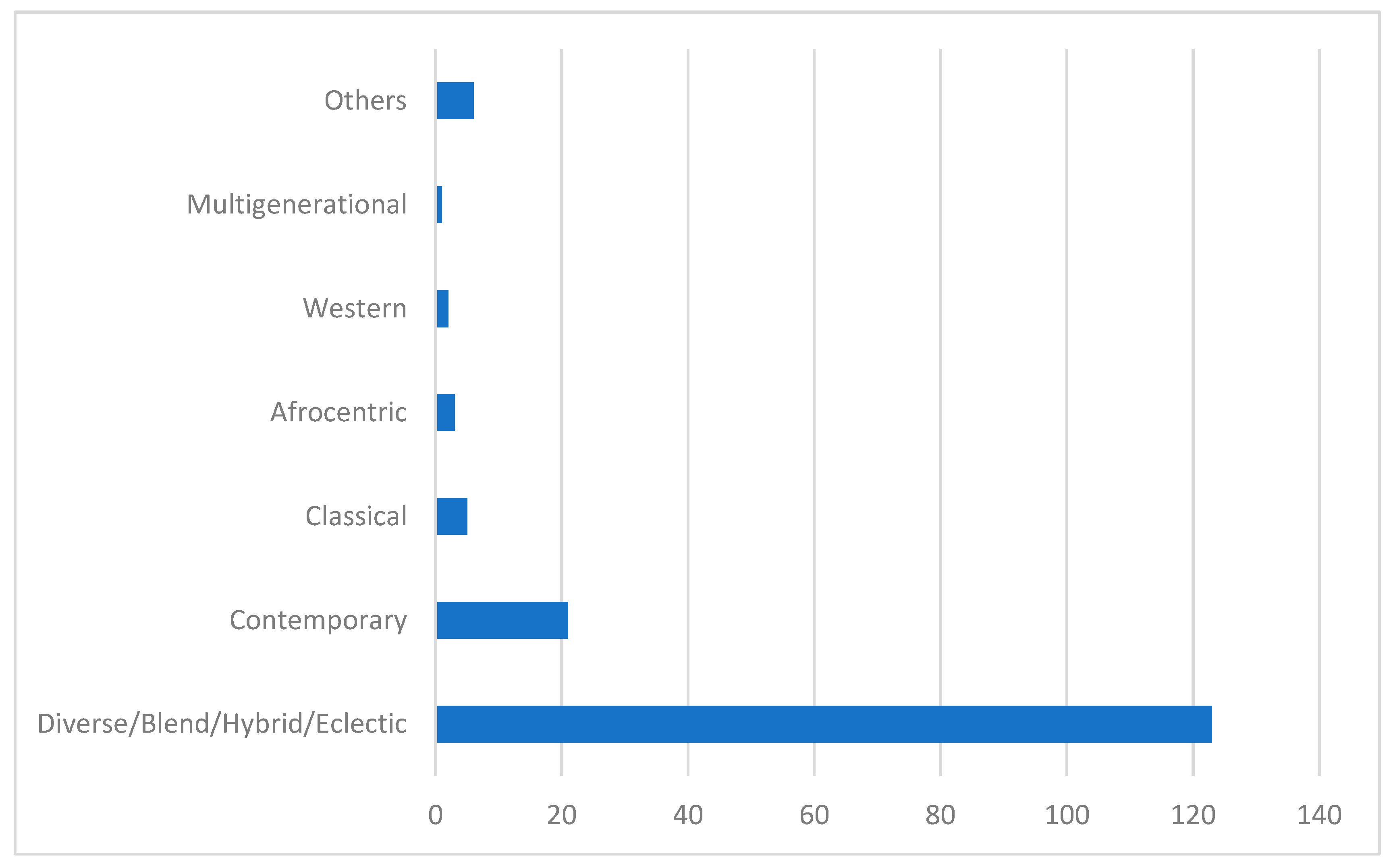

In addition to observing worship services in the three churches mentioned above, I conversed with church leaders and members through in-person and online mediums. In the online survey, I asked respondents to describe their church’s worship styles. Figure 2 shows the graphical representation of most respondents’ terminologies for describing worship styles in their churches.

Figure 2.

Congregational worship styles.

The above responses indicate ways congregants describe congregational worship in Nigeria. The description of worship styles has implications for what to expect in congregational music. Although music does not equal worship, for worship can exist without music, many worshippers view music and worship as inseparable (Segler and Bradley 2006, p. 110). However, we cannot rule out the functional nature of music in congregation worship. According to Franklin Segler and Randall Bradley, “Music provides an expression for our most exuberant praise and lament for our grief. Music is present within all the functions of the Christian community; it accompanies all the actions of our lives through which God can be present” (Segler and Bradley 2006, p. 110).

My ethnographic study of Lagos churches reveals that congregational music intersects, defines, or reflects local worship styles. In this regard, congregational singing in Nigeria embodies musical localization, incorporating the ‘local’ and ‘foreign’ ways of making music. Local artists navigate political, power, and cultural boundaries while mediating musical practices. While the Western culture—English language, singing hymns, anthems, and instruments—is retained in most churches, multilingual music has remarkably marked the localization of Nigerian church music. Nigerian gospel music continues to evolve in the twenty-first century with the increasing fusion of local and foreign elements, such as the vernaculars, English, and indigenous and Western instruments. This recent practice is exemplified in the Wazobia gospel music. However, before Wazobia gospel music emerged, Nigerian Christian music evolved from a confluence of Western and African music traditions.

6. De-Colonization or Africanization of Church Music?

In order to understand the significance of Wazobia gospel music, it is necessary to take a cursory view of what suggested the Africanization of music within the church.15 The introduction of church music by missionaries who came to Africa was closely associated with Europe’s colonization and Christianizing project (Ojo 1998; Sadoh 2009). At the advent of Christianity in Africa in the nineteenth century, converts were prohibited from singing folk songs or playing indigenous musical instruments (Ojo 1998, p. 212). Instead, Western hymns, musical instruments, and European tonality were imposed on Africans (Idamoyibo 2005; Odewole 2018, p. 5). Solemnity in worship in the early mission-oriented churches meant “no dancing, no clapping of hands” (Ademiluka 2023, p. 1). In this regard, the Anglican, Methodist, Catholic, and Baptist Missionaries adopted the European forms of expression in worship. In other words, some leaders of these mission churches initially invalidated the whole corpus of African practices—including drumming and dancing in worship. However, the early twentieth century witnessed the impact of The African Church Movement in Africa, which sought to integrate local cultural expressions into Christian worship. One of the issues that dominated the early history of the African Church Movement was the question of African forms of music and worship (Sanneh 1983). According to missiologist Lamin Sanneh, amongst other controversial elements, this development led to the introduction of drumming in worship and African versions of Western hymns (Sanneh 1983, p. 177). In describing the Africanization of worship in Kenya, Jean Kidula argues that by the 1980s, the manner and content of East African gospel music had succeeded in breaking away from missionaries’ performance and sonic expectations (Kidula 2000, p. 412).

The Africanization of Christian worship became a watershed for the emergence of charismatic churches and the Pentecostals in Africa (Sanneh 1983, p. 180). Africans demanded Christianity, which reflected their own cultural context. This development suggests a form of religious adaptation in Africa, showing how Christian conversion was negotiated. As rightly observed by Zimbabwean scholar Ezra Chitando, “The introduction of vernacular hymns and choruses, indigenous instruments, and oral traditions in church music meant that while Africans converted to Christianity, they were also converting Christianity to African cultural realities. Cultural interaction has never been a one-way affair but has always entailed creating new horizons for encounters” (Chitando 2002, p. 91). This new horizon includes using African languages and idioms in Christian worship. In the mid-twentieth century, several African churches began exploring making singing relatable to local people. In my research, I encountered this growing process of decolonizing African Christian liturgy in the fusion of traditional dance, Western hymn singing, drumming, and singing in contemporary Christian worship. These expressions were incorporated into musical localization and signification concepts, which I discussed earlier. The Wazobia gospel music embodies the continuation of musical localization, signification, and globalization.

7. The Emerging Wazobia Gospel Music

The current wave of intertextuality in local song-texts in Nigeria is unprecedented in its sheer volume, visibility, extent, preponderance, and intricacy.16 The twenty-first-century reconstruction of Nigerian gospel music to signal localization and also aspire to globalization, involving such activities as using English/Pidgin and vernaculars to relate to wider audiences, has inaugurated a new Nigerian gospel genre―what I am calling Wazobia gospel music. Another prominent concept in the performance practice of the Wazobia gospel is code-switching/code-mixing. Code-switching and code-mixing are sociolinguistic phenomena commonly observed in bilingual and multilingual speech communities. Scholars such as J. K. Chambers (2009), Miriam Meyerhoff (2019), and Banda (2019) have widely discussed the intricacies concerning literary language and conversation. These authors have conceptualized the intersections between communication and multilingualism. In particular, Miriam Meyerhoff’s book Introducing Sociolinguistics critically examines attitudes to language by exploring Social Identity Theory (SIT) and Accommodation Theory (Meyerhoff 2019, p. 78). SIT is “a social psychological theory holding that people identify with multiple identities, some of which are more personal and idiosyncratic and some of which are group identifications” (Meyerhoff 2019, p. 78). SIT is a theory of intergroup relations in which language is one of many potent symbols individuals can use strategically when testing or maintaining group boundaries (Meyerhoff 2019, p. 78). Accommodation Theory has much in common with the tradition of Social Identity Theory. Its principles are intended to characterize speakers’ strategies to establish, contest, or maintain relationships through communication (Meyerhoff 2019, p. 80). SIT and Accommodation Theory explain an aspect of negotiating language boundaries in Wazobia gospel music. However, code-switching/code-mixing appears to be a more noticeable concept in the performance practice of Wazobia gospel music.

Many Nigerian scholars have written extensively on code-switching and code-mixing in Nigerian popular and gospel music; examples include M. O. Ayeomoni (2006), Anas Sa’idu Muhammad (2023), Naomi Chimene-Wali (2019), and Jacob Oluwadoro (2021). Drawing from song lyrics, Naomi Chimeni-Wali investigated how the major languages spoken in Rivers State (south-south, Nigeria) are mixed and switched in gospel music. The study reveals that code-mixing and switching signal globalization and localization as gospel singers use English/Pidgin and vernaculars to relate to a broader fan base and connect with their roots (Chimene-Wali 2019, p. 11). In this regard, the gospel artists studied by Chimeni-Wali alter/mix codes to create gospel music that most locals and non-native speakers will embrace. Similarly, Oluwadoro opines that gospel artists engage in this concept to gain their acceptance, knowing full well that code-mixing is a common feature among the youth in most cosmopolitan Nigerian cities (Jacob Oluwadoro 2021, p. 31). My research builds on the above studies by incorporating ethnographic studies and current examples of songs from Nigerian gospel artists.

Prominent Nigerian gospel artists who fuse different languages and multicultural elements in their music include Nathaniel Bassey, Mercy Chinwo, Tim Godfrey, and David G. In the following section, I demonstrate three examples of Wazobia gospel music by exemplifying its textual categories through the concepts of code-switching/code-mixing and multilingual medley. I also discuss the distinct sonic nature of Wazobia gospel music by describing its main musical components.

- “Chinedum (God Leads Me)” by Mercy Chinwo

The first example of Wazobia expression is a song by Mercy Chinwo, a Nigerian Gospel musician, singer, and songwriter raised in Port Harcourt who mostly ministers in Lagos.17 The lyrics of the song Chinedum combine three languages: Igbo, English, and Nigerian Pidgin. The song begins with a verse in Igbo and then moves into a multilingual chorus. An excerpt of the lyrics from the chorus is as follows:

Chinedum mo (guided by God)Anywhere you lead me, I will goMe ago follow you dey go (I will follow you)Anywhere you lead me, I go, go (anywhere you lead me, I will go)

The song Chinedum presents God as the one who leads and guides and whose leadership always brings good results. After repeating the chorus, the artist breaks entirely away from Igbo, the initial code in which the music started, into English and Nigerian Pidgin. The song ends with repeating the Igbo Chinedum mo (guided by God).

- “No One Like You” by Eben

The second example is by Emmanuel Benjamin, known as Eben.18 He is a Nigerian gospel singer, vocalist, and songwriter in Lagos. This song features another prominent Nigerian gospel artist, Nathaniel Bassey. The text of this track in the album combines Nigerian Pidgin, English, Yorùbá, and Igbo. The text begins with the use of a global trope ‘oh’ added to the word ‘man’, such as ‘man oh’19 and then adds the Igbo Eze (a term for King) in the second part:

You’re not a man, ohYou’re not a man, ohYou’re the God who opens doors no man can shutYou’re not a man, ohYou’re the God of everything no man like you.No one like you, JesusNo one like you, EzeNo one like you, Father.

The song acknowledges that no one can compare to God, the King, playing with the word Eze (in Igbo known as King) and then referencing Jesus, Father, and Master. At the song’s end, the writer introduces additional code-mixing in the line “No One Like You, Atofarati, Awimayehun, Aledewura”. Here, the writer introduces three Yoruba words: Atofarati (dependable), Awimayehun (one whose words never change), and Aladewura (one with the crown of gold).

- “My Trust is in You” by David G.

The third example, “My Trust is in You” is a song produced by gospel artist David Gbenga, also known as David G.20 The song text combines five languages: English, Igbo, Yorùbá, Idoma, and Hausa. The song begins with the first verse and chorus in English:

Lion of JudahMy trust is in youAncient of DaysMy trust is in you

Other verses switch to a combination of English and the vernaculars (Igbo, Yorùbá, Hausa, and Idoma) as follows in the excerpt:

Isi ikendu (Igbo: The streams of life)My trust is in youMy trust is in youSeriki duniya (Hausa: Master of the universe)My trust is in youObadabada (Idoma: Massive God)My trust is in you.

The above song’s lyrics carry a clear and repetitive message, emphasizing the artist’s trust and confidence in God. The song demonstrates names and titles attributed to God in English and the vernacular. Like most Nigerian Wazobia gospel artists, David G. uses code-switching/mixing of local dialects and English texts to construct meanings. In other words, using multiple languages is complementary and reflects the musician’s cultural context.

Another performance practice of Wazobia gospel music involves singing a medley of songs in different languages. Although the multilingual medley arrangement may also incorporate code-switching or code-mixing features, as discussed above, it usually employs language sequentially. For example, “High Praise 1”, a song released by the Redeemed Christian Church of God (RCCG) in 2006, consists of a medley beginning with “Come and See the Lord is Good” and “Thank You So Much, Lord Jesus”, which is repeated in Yorùbá, (Olúwa mi Mo Dúpé) and Igbo (Chineke Nna Imela), and later switched to Urhobo (Otega Oghene Tega). The RCCG medley is representative of the multilingual medley that continues to evolve among gospel music groups and in Nigerian congregations. This singing style uses several repetitions, call and response, lyrical tunes, and highly rhythmic instruments.

The above examples showcase some of the performance practices of Wazobia gospel music. Using English or Pidgin English and vernaculars to relate to wider audiences has become a common feature of Wazobia gospel music. What might this mean for the Wazobia gospel genre?

8. “Bringing Them Home”: Musical Worship, Signification, and Identity

Wazobia gospel music signifies ethnic identity that holds profound meaning for participants. Meaning in music is localized. What appears meaningful in a culture may not resonate with another culture’s values, ethics, quirks, and expectations. What does singing mean in a culture? Is there a relationship between musical style and congregational response? These questions highlight the important role of signification, in other words, understanding music’s significance as a peculiar human experience.22 Timothy Rice’s idea of signification corroborates Akin Euba’s argument that signifiers of ethnic identity in local music have always been one of the most vital features of African traditional culture, and arguably, ethnic diversity has been an enriching rather than constricting factor (Euba 2001, p. 120). By implication, in the African context, music (as sound or text) can communicate or mediate meaning at an individual and community level.23

That music makes meaning to people when it resonates with their culture is true in both popular music and church music. I found this to be true in my research. When I asked one of my interviewees, a local church musician, why he incorporated songs in native dialects and local instruments, he said, “The intercultural expressions will bring them home”. By this, he means that when people hear sounds from their native culture, they engage more in worship. This meaning-making is reflected in how congregants relate to music and native languages. For example, in the survey I distributed to various Christian worshipers in Lagos, I asked congregants what the most positive aspects of singing in their native dialect were. Some of my respondents answered as follows:

“It is something I can connect with. It’s the language I grew up with … Praising God in my mother tongue makes me feel more connected with him”.

“It brings greater meaning and better understanding”.

“It makes worship more meaningful to me”.

“It gives me a sense of identity that Christ is for all races, not just a few sects”.

“It facilitates deep meanings, awesome connection, nostalgia, personalized experiences”.

The primary themes from my survey related to the question above include feeling a deep connection with God, worshipping with understanding, enhancing participatory worship, engaging with worship on a deeper level, and affirming identity.

9. “Reaching Many People”: Musical Worship and Hospitality

A second role of Wazobia gospel music is to create a space for hospitality. The word “hospitality” readily reminds us of guests, visitors, or strangers’ friendly and generous reception and entertainment. Church music scholars and practical theologians have used the term to demonstrate the practices of welcoming and integrating people into worship. According to Randal Bradley, “Music is a fit receptacle for embodying the hospitality of Christ. When we offer music to someone, we are serving as host; when we receive music, we, as guests, accept it as a gift. Ideally, music functions in the reciprocal gift-giving roles of host and guest and readily serves as welcome to the stranger” (Bradley 2012, p. 168).

The above indicates that music functions as hospitality in two ways—giving and receiving. Bradley reiterates music as an agent for the church’s hospitality by highlighting areas such as music being ‘multilingual’ and ‘inclusive’, among others.24 Music is multilingual when it can speak “multi-musical languages”. This idea suggests music speaking a language of several musical styles that can resonate with worshipers’ experiences (Bradley 2012, p. 172). In the same way, to create avenues of communication, “attempting to speak/sing/perform musical language that is familiar to another also facilitates dialogue” (Bradley 2012, p. 173). In addition, Bradley states that music is hospitable when it promotes inclusiveness and accessibility (Bradley 2012, p. 173). In other words, the church’s music should be functional by attempting to serve everyone in the congregation. I found Bradley’s theory of musical hospitality useful in describing one of the functions of Wazobia gospel music.

Multilingual singing has enabled Nigerian gospel artists to reach many people. During an interview, one of the local artists mentioned that writing songs incorporating many languages has helped him to “reach many people across language and ethnic divides”.25 My interviewee notes that besides receiving inspiration from God, he writes multilingual music as a deliberate attempt to encourage participatory singing. According to him, people often identify with English, but when they hear other local languages alongside, they are encouraged to participate on a deeper level. What my interviewee said above relates to some of my survey responses. When I asked my respondents what the most positive aspects of singing in other people’s dialects are, some said:

“It engenders a sense of unity and belonging in diversities. This action builds fellowship and community in the church”.

“It helps me connect with the diversity of language and also know that a language does not limit God”.

“It brings variety into our worship and allows the minority ethnicities in our congregation to have a sense of belonging”.

“It makes the act of singing in worship more intentional. When I enjoy a song in another language, I must seek its meaning. I tend to be more conscious when singing it and avoid the risk of singing mindlessly”.

“It helps me to learn how other people see/think about God”.

The action above can be described as a convergence, expressing spirituality and hospitality. According to Constance Cherry, being hospitable in worship involves more than being friendly or personable; it requires deliberate attempts to incorporate various participation dynamics (Cherry 2021, p. 300). In Cherry’s argument, hospitality involves designing and leading inclusive worship services―worship designed to invite the ongoing participation of all worshipers and encourage them to offer themselves fully in worship. Cross-cultural musical participation may contribute to our sense of musical hospitality. As Michael Hawn notes:

Using music from other cultures does not necessarily imply combining styles into one “universal” form. On the contrary, it is an acknowledgment of and participation in diverse voices within a liturgical structure. Inevitably, the juxtaposition of styles influences each other. Cross-cultural musical participation implies, however, that we attempt to appreciate sui generis, the contribution of each perspective to our understanding of God (Hawn 2005, p. 103).

But can we say all worshipers are truly included in musical worship? My fieldwork revealed some levels of exclusion in the practice of Wazobia gospel music.

10. “Disconnect… I Don’t Understand the Dialect!”

Thus far in this article, I have demonstrated that Wazobia gospel music embodies identity, enables diversity, and promotes inclusion. As such, it would seem to be a perfect repertoire for congregational singing, for one of its goals is to engage worshipers in meaningful, participatory singing experiences. Within the participatory tradition, “Participatory values are distinctive in that the success of a performance is more importantly judged by the degree and the intensity of participation than by some abstracted assessment of the musical sound quality” (Turino 2008, p. 33). In other words, we may understand participation in congregational singing by the degree to which people feel included in the performance. It appears congregants do not feel included in Wazobia gospel music in the same way.

In analyzing responses to my online survey, I found out that multilingual songs allow for inclusion and participation but can also pose exclusion risks. When I asked my respondents to mention what they think may be a disadvantage of participating in congregational Wazobia gospel music, responses highlighted feelings of “disconnect” and “exclusion”.26

“It can cause exclusion and a lack of a sense of belonging for non-native speakers of the languages sung”.

“There could sometimes be a disconnect in understanding the song’s meaning”.

“When the majority don’t understand the meaning, and it’s not properly introduced, people don’t follow”.

“Some worshippers may be excluded from worship when they do not know the dialect or languages sung”.

“Unless translated into English, not everyone would understand the meaning of the songs”.

The above shows that the degree to which multilingual songs promote inclusion and exclusion in worship varies from one congregation to the other. The questions raised by multilingual singing offer an opportunity to reexamine Nigerian Christian worship practices and what expressions of congregational embodiment they privilege and marginalize. Cross-cultural music, such as Wazobia, is meaningful when understood as a participatory experience that includes rather than excludes.

11. Considerations and Conclusions

The development of Wazobia gospel music marks a new turn in Nigerian gospel music since the mid-twentieth century. However, the Wazobia gospel music genre, due to developments in digital media and the internet, gained renewed momentum in the twenty-first century. Wazobia gospel music utilizes an increasing combination of local and foreign musical cultures, such as using various vernacular combined with English and incorporating indigenous and Western instruments. As I reflect on my interaction with church members, church music practitioners, gospel artists, and scholars, it is necessary to point out that the meaning of Wazobia Gospel music is multifaceted, and its roles and functions differ in different contexts. In cultural music study, music identity is often legitimized by what the society in question has acknowledged and accepted (Kaemmer 1993, pp. 64–65). In other words, music identity is usually situated within specific cultural interpretations. Based on my research with some Lagos Christian congregations, the interactions between music and language significantly influenced how Wazobia gospel music identities are shaped and constructed. Through its unique use of multiple languages and musical styles, the Wazobia gospel music genre enables its adherents to identify with the music and relate to its relevant cultural messages. The Wazobia gospel genre has played a pivotal role in shaping the complex soundscape of the Nigerian gospel music industry and its intersection with Nigerian congregational singing. The convoluted meanings, functions, and identities of the Wazobia gospel music genre largely reflect the dynamics of Nigeria’s social, political, economic, and religious complications. But what does this leave us with congregational singing?

Musical worship is beyond just making ethnic or tribal song lists. Certain questions are pertinent to worship leaders and songwriters. What determines the selection of songs from a particular ethnic group in corporate worship? What motivates worship leaders to incorporate multilingual songs? Why do gospel artists write multilingual songs? Is it to reach a broader ministry audience? Is it to galvanize local and international recognition or for market expansion? Worship is first an engagement with God. In congregational worship, our first purpose is not to “get something out of worship” but to extend to God glory and adoration (Malefyt and Vanderwell 2005, p. 135). In other words, pleasing God and not tribe or ethnicity should be the focus in writing or selecting songs for corporate worship. However, congregational worship should be integrated into the whole life of the congregation by being sensitive to the demographics and cultural intelligence of worshipers. Part of this integration in a multilingual setting is for worship leaders to carefully plan God-honoring and edifying musical worship and culturally relevant musical expressions broadly relatable to worshipers.

The study on Wazobia gospel music offers three significant resources to church music scholars and practitioners. First, the study has provided a conceptual framework for describing, interpreting, and understanding the intersection of languages, cultures, and music in Nigerian contemporary congregational singing. Second, the study joins the growing scholarship on decolonization. There have been several recent calls for church music scholarship to be “decolonized”, both in terms of how it is approached (Steuernagel 2020, pp. 24–32) and what voices contribute to it (Ingalls et al. 2024, p. 246). Scholars and practitioners have been working to expand the canon of church music to include songs from around the world and “finding hospitable ways to give these repertoires and practices a seat at the communal table of global church music” (Steuernagel 2020, p. 32). Recent scholarly works provide decolonial resources to challenge and remake Christian musical canons (Ingalls et al. 2024, p. 234; Moshugi 2024, p. 215). My study on Wazobia gospel music combines several interdisciplinary research tools and incorporates conversations with local artists, oral historians, sociolinguists, theologians, church members, and church musicians. This approach represents contemporary reflections and responses within postcolonial discourse. Significantly, it amplifies the voices and practices of Christians and music often absent from church music discussions, fostering a more inclusive dialogue.

Finally, this study provides different tools, methods, and concepts from which anyone thinking about multicultural worship can draw. Scholars in church music studies and related fields can continue to engage meaningfully with this emerging concept regardless of where the communities they study are located. Reflecting on the intersection of gospel music, languages, and cultures in a Nigerian setting contributes to new vistas in congregational music studies.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Baylor University Center for Christian Music Studies (protocol code 1253219-1, approved on 27 October 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Nigeria’s musical practices are vastly diverse. The genres mentioned above are primarily popularized in South and Southwestern Nigeria and have substantially attracted global attention. |

| 2 | The claim about Nigeria’s potential population growth and its implication for global relevance has been identified. For example, UN statistics show that Nigeria will surpass the USA population by 2050. This data has implications for potential musical development that may arise from the surge in Nigeria’s population and the key role this may play in gospel music worldwide. See “World Population Projected to Reach 9.7 Billion by 2050 with Most Growth in Developing Regions, Especially Africa–Says UN”, https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/pdf/events/other/10/World_Population_Projections_Press_Release.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2024). |

| 3 | Adedeji’s (2005) provides a comprehensive overview of the evolution of Nigerian gospel music, making it a valuable resource for understanding the historical context of this genre. |

| 4 | The colonial British government in Nigeria recognized the three major languages, Hausa, Yorùbá, and Igbo, as the primary communication languages after English. Subsequently, the Nigerian constitution recognized these languages as the primary communication languages. See John Chidi Nwafor (2002, p. 24). |

| 5 | Nigerian Pidgin is English modified by another language or multiple other languages. Pidgin English in West Africa emerged by the early 19th century as a language of trade, a medium of communication between Africans and European traders. It is argued that Nigerian Pidgin English could be considered a language in its own right. See Philip Atsu Afeadie (2015). |

| 6 | Wazobia, F.M. https://www.wazobiafm.com/ (accessed on 13 December 2022). |

| 7 | The Wazobia African Market in Houston also operates a Wazobia kitchen for prepared Nigerian food. Customers can make orders for home deliveries or visit two locations: Westheimer and Beechnut in Houston. See “Wazobia African Market”, https://wazobia.market/ (accessed on 13 December 2022). |

| 8 | I borrowed this concept from Mellonee Burnim, considering my position as both a scholar of gospel music and a “culture bearer”, a member of the culture under investigation. See Burnim (1985). |

| 9 | The “hybrid field” as a conceptual shift in ethnography became more relevant after the recent COVID-19 pandemic. This disruption has encouraged online presence in most churches in Nigeria and across the globe. In this study, I engaged in an online-mediated platform in addition to the physical fieldwork site. See Przybylski (2020). |

| 10 | Since some of my conversation partners prefer anonymity, I have generally excluded the names of individuals and their churches from the article. |

| 11 | Some prominent studies on church music and language in Nigeria have focused on the intersection of media and gospel music, as well as church music and identity. See (Brennan 2018; Brennan and Nyamnjoh 2015; Adedeji 2001). |

| 12 | After establishing contacts in the three churches, I leveraged my relationships to extend surveys to other churches. I sent links to ministers, worship leaders, music directors, friends, and family connections. The churches represent eight Baptist churches and seven Pentecostal churches. |

| 13 | Twenty-eight ethnicities/languages participated in this online survey. The leading languages are Yorùbá, Igbos, Ijaw, and Hausa. |

| 14 | Constance M. Cherry, a prominent figure in the field, provides a comprehensive guide in her book, (Cherry 2021, p. 246). |

| 15 | This expression is not used the same way by all scholars alongside other terms such as localization, indigenization, inculturation, and contextualization. I employ the Africanization of music as a subset of contextualization, referring to the contextualization of worship, theology, and polity within sub-Saharan Africa’s specific cultural and sociopolitical context. See Brown-Whale (1993, p. 5). |

| 16 | I adopted Joyce Nyairo’s description of East African popular music culture. By this expression, Nyaro describes processes of exchange where East African artists derive local styles from examples of American popular music. See Joyce Nyairo (2008, p. 72). |

| 17 | Mercy Chinwo draws 615 k subscribers on YouTube, 5.1 million followers on Facebook, and 3.3 million followers on Instagram. See “Mercy Chinwo”, YouTube Channel, 26 September 2023. https://www.facebook.com/mercychinwoofficial/ (accessed on 26 September 2023). |

| 18 | Eben attracts 399.3 k followers on YouTube and 678 k followers on Instagram. See https://www.instagram.com/eben_rocks/?hl=en (accessed on 16 April 2024). |

| 19 | In Nigeria, vernacular and Pidgin speakers use such words as oh! ah! yee! and whoa! to emphasize another word in a statement. The expressions are also employed in singing. |

| 20 | David G. attracts about 20 k subscribers on YouTube and 55.1 k followers on Instagram. See https://www.instagram.com/officialdavid.g/?hl=en (accessed on 17 April 2024). Regarding social media presence, David G does not rank in the league of other artists cited in the article; I included his example to reflect a rare single song incorporating four Nigerian languages: Hausa, Idoma, Yorùbá, and Igbo. |

| 21 | In African Traditional Religions, Oyigiyigi is a word that depicts Ifa creation myth, which shows that the universe emerges from the Eternal Rock of Creation called Oyigiyigi. See https://research.auctr.edu/Ifa/Chap7Hermeneutics (accessed on 7 September 2024). |

| 22 | The word ‘signification’ in describing musical meaning has multiple meanings, depending on the context in which it is used. Here, I borrow the concept from Timothy Rice, using musical meaning to refer to a broad range of functions and values that concurrently align with the term ‘signification’ and other terms like ‘indication,’ ‘index’, ‘icon’, ‘representation’, and ‘symbol’. See Rice (2017, pp. 89–90). |

| 23 | This view is corroborated in a study of Macumba-Christianity in Salvador, Brazil, which explores the psychological and spiritual function of movement and dance as mediators of meaning. The Macumba-Christian community engages in movement and dance to connect and make meaning of their ancestral history and identity. The history of Macumba-Christianity is linked with the Yorùbá tribe. The people and their traditions, culture, and spirituality were brought from Portuguese colonies in Africa to Brazil in the 1500s. See DeMarinis (2001, pp. 195–200). |

| 24 | Other metaphors Bradley uses to describe music hospitality include “music is welcome”, “music is embodied”, “music is intergenerational”, and “music is abundance”. Bradley (2012, pp. 171–76). |

| 25 | I interviewed Prospa Ochimana on 4 January 2024 (Ochimana 2024). Prospa Ochimana is a Nigerian songwriter, music producer, and worship leader who has won many awards in the Nigerian gospel music industry and the diaspora. Prospa’s use of native Igbo and Igala languages has added flavor to Nigerian congregational singing. “Ekueme”, “Dojima Nwojo”, and “Chioma” are a few examples of his songs commonly sung in some Nigerian churches. Prospa shares various perspectives on indigenous contemporary music in Nigeria and his philosophy of music ministry. During the interview, I discovered that Prospa studied linguistics at the undergraduate level. It is interesting to note how his degree in linguistics has enhanced his songwriting and music performance. |

| 26 | Several of my respondents put “none” in this column. The ten responses highlighted represent how Wazobia gospel music may exclude several worshippers. This has implications for church leaders and music practitioners when planning music for worship services. |

References

- Adedeji, Femi. 2001. Definitive and Conceptual Issues in Nigerian Gospel Music. Nigerian Music Review 2: 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Adedeji, Femi. 2005. Historical Development of Nigerian Gospel Musical Styles. African Notes: Journal of the Institute of African Studies 29: 145–52. [Google Scholar]

- Adedeji, Femi. 2010. Language Dynamics in Contemporary African Religious Music: Nigerian Gospel Music as a Case Study. Journal of the Association of Nigerian Musicologists 4: 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ademiluka, Solomon O. 2023. Music in Christian Worship in Nigeria in Light of Early Missionary Attitude. Verbum et Ecclesia 44: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeola, Shola Taiye. 2021. Intersections of Popular Culture and Nigerian Gospel Music. In Culture and Development in Africa and the Diaspora. London: Routledge, vol. 1, pp. 84–94. [Google Scholar]

- Afeadie, Philip Atsu. 2015. Language of Power: Pidgin English in Colonial Governing of Northern Nigeria. Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana 17: 63–92. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26512470 (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Animashaun, Oyesola. 2020. Bifurcated Citizenship in Nigerian Cities: The Case of Lagos. African Renaissance 17: 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeomoni, Moses Omoniyi. 2006. Code-Switching and Code-Mixing: Style of Language Use in Childhood in Yoruba Speech Community. Nordic Journal of African Studies 15: 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Banda, Felix. 2019. Beyond Language Crossing: Exploring Multilingualism and Multicultural Identities Through Popular Music Lyrics. Journal of Multicultural Discourses 14: 373–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, Randall C. 2012. From Memory to Imagination: Reforming the Church’s Music. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, Vicki L. 2018. Singing Yoruba Christianity: Music, Media, and Morality. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, Vicki L., and Francis B. Nyamnjoh. 2015. Ṣenwele Jesu: Gospel Music and Religious Publics in Nigeria. In New Media and Religious Transformations in Africa. Edited by Rosalind I. J. Hackett and Benjamin F. Soares. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 227–44. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt16gzgjx.17 (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Brown-Whale, Richard Edward. 1993. Africanizing Worship in the Mission Churches of Africa. ProQuest D. Min. Professional Project, Claremont School of Theology. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/304081292/abstract/8705815F8A764DC5PQ/1 (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Burnim, Mellonee V. 1985. Culture Bearer and Tradition Bearer: An Ethnomusicologist’s Research on Gospel Music. Ethnomusicology 29: 432–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, Jack K. 2009. Sociolinguistic Theory: Linguistic Variation and Its Social Significance. Chichester: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, Constance M. 2021. The Worship Architect: A Blueprint for Designing Culturally Relevant and Biblically Faithful Services. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Chimene-Wali, Naomi. 2019. Code Switching and Mixing in Nigerian Gospel Music. Scholarly Journal of Science Research and Essay 9: 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chitando, Ezra. 2002. Singing Culture: A Study of Gospel Music in Zimbabwe. Uppsala: Nordiska Africainstitutet. [Google Scholar]

- DeMarinis, Valerie. 2001. Movement as Mediator of Meaning: An Investigation of the Psychosocial and Spiritual Function of Dance in Religious Ritual. In Dance as Religious Studies. Edited by Doug Adams and Diane Apostolos-Cappadona. New York: Crossroad Publishing Company, pp. 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Duck, Ruth C. 2013. Worship for the Whole People of God: Vital Worship for the 21st Century. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. [Google Scholar]

- Euba, Akin. 2001. Text Setting in African Composition. Research in African Literatures 32: 119–32. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3820908 (accessed on 13 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Falola, Toyin, and Matthew M. Heaton. 2008. A History of Nigeria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hawn, Michael C. 2005. Reverse Missions: Global Singing for Local Congregations. In Music in Christian Worship. Edited by Charlotte Kroeker. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, pp. 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- Idamoyibo, Atinuke Adenike. 2005. The New Ìjálá Genre in Christian Worship. African Notes: Journal of the Institute of African Studies 29: 153–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ingalls, Monique M., Ayobami A. Ayanyinka, and Mouma Emmanuella Chesirri. 2024. Reconstructing Hymn Canons Through International Partnership: ‘The Nigerian Christian Songs’ Project as Cultural Archive, Pedagogical Tool, and Decolonial Resource. In Hymns and Constructions of Race: Mobility, Agency, and De/Coloniality. Edited by Erin Johnson-Williams and Philip Burnett. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ingalls, Monique Marie, Muriel Swijghuisen Reigersberg, and Zoe C. Sherinian. 2018. Introduction: Music as Local and Global Positioning: How Congregational Music-Making Produces the Local in Christian Communities Worldwide. In Making Congregational Music Local in Christian Communities Worldwide. Edited by Monique Marie Ingalls, Muriel Swijghuisen Reigersberg and Zoe C. Sherinian. London: Routledge; Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 18–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kaemmer, John E. 1993. Music in Human Life: Anthropological Perspectives on Music. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kidula, Jean Ngoya. 2000. Polishing the Luster of the Stars: Music Professionalism Made Workable in Kenya. Ethnomusicology 44: 408–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liadi, Olusegun Fariudeen. 2012. Multilingualism and Hip-Hop Consumption in Nigeria: Accounting for the Local Acceptance of a Global Phenomenon. Africa Spectrum 47: 3–19. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23350429 (accessed on 13 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Malefyt, Norma de Waal, and Howard Vanderwell. 2005. Designing Worship Together: Models and Strategies for Worship Planning. Herndon: The Alban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhoff, Miriam. 2019. Introducing Sociolinguistics, 3rd ed. London: Routledge; Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Moshugi, Kgomotso. 2024. Decolonizing a Hymn through its Mobility: A Case of Re-location and Altered Musical Aesthetics. In Hymns and Constructions of Race: Mobility, Agency, and De/Coloniality. Edited by Erin Johnson-Williams and Philip Burnett. New York: Routledge, pp. 198–217. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, Anas Sa’idu. 2023. The Changing Linguistic Codes in Hausa Hip-Hop Songs. Studies in African Languages and Cultures 57: 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey. 2002. Nigeria. In Nigeria: Current Issues and Historical Background. Edited by Martin P. Matthews. New York: Nova Science Publishers, pp. 18–50. [Google Scholar]

- Nettl, Bruno. 1992. Recent Directions in Ethnomusicology. In Ethnomusicology: An Introduction. Edited by Helen Myers. New York: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Nwafor, John Chidi. 2002. Church and State: The Nigerian Experience: The Relationship Between the Church and the State in Nigeria in the Areas of Human Rights, Education, Religious Freedom, and Religious Tolerance. Frankfurt am Main: IKO, Verlag für Interkulturelle Kommunikation. [Google Scholar]

- Nyairo, Joyce. 2008. Kenyan Gospel Soundtracks: Crossing Boundaries, Mapping Audiences. Journal of African Cultural Studies 20: 71–83. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25473399 (accessed on 18 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ochimana, Prospa. 2024. Gospel Music and Multilingual Singing in Nigeria. Oral Interview with the author. [Google Scholar]

- Odewole, Israel O. 2018. Singing and Worship in an Anglican Church Liturgy in Egba and Egba West Dioceses, Abeokuta, Nigeria. Hervormde Teologiese Studies 74: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, Matthew A. 1998. Indigenous Gospel Music and Social Reconstruction in Modern Nigeria. Missionalia 26: 210–30. [Google Scholar]

- Oluwadoro, Jacob Oludare. 2021. Code Alternation in Nigerian Gospel Music: A Matrix Language Frame Analysis. International Journal of English Literature and Culture 9: 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Oyetade, Oluwole S. 1992. Multilingualism and Linguistic Policies in Nigeria. African Notes: Journal of the Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan 16: 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Patsiaoura, Evanthia. 2018. Bringing Down the Spirit: Locating Music and Experience among Nigerian Pentecostal Worshippers in Athens, Greece. In The Routledge Companion to the Study of Local Musicking. Edited by Suzel A. Reily and Katherine Brucher. London: Routledge, pp. 167–18. [Google Scholar]

- Przybylski, Liz. 2020. Hybrid Ethnography: Online, Offline, and in Between. Washington, DC: Sage Publication, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, Timothy. 2014. Ethnomusicology: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, Timothy. 2017. Modeling Ethnomusicology. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sadoh, Godwin. 2009. Modern Nigerian Music: The Postcolonial Experience. The Musical Times 150: 79–84. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25597642 (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Sanneh, Lamin. 1983. West African Christianity: The Religious Impact. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Segler, Franklin M., and Randall Bradley. 2006. Christian Worship: Its Theology and Practice, 3rd ed. Nashville: B & H Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Steuernagel, Marcell Silva. 2020. Towards a New Hymnology: Decolonizing Church Music Studies. The Hymn: A Journal of Congregational Song 71: 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Tomori, Olu S. H. 1985. Aspects of Language in Nigeria. In Nigerian History and Culture. Edited by Richard Olaniyan. Harlow: Longman, pp. 284–305. [Google Scholar]

- Turino, Thomas. 2008. Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).