Abstract

During the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period, most Jews lived as a minority under Christian or Islamic rule. By contrast, the Ethiopian Jews, the Betä Ǝsraʾel, maintained political autonomy in parts of Ethiopia until the seventeenth century. From the fourteenth century, they were engaged in a series of wars against the Christian Solomonic Kingdom. Following Christian military victories over the Betä Ǝsraʾel, the victors erected churches in the newly conquered lands. Some were built on the sites of battles and over Betä Ǝsraʾel strongholds to commemorate the Solomonic victory. While churches dedicated to historical events are common, those memorializing Christian military victories over Jews are largely without parallel elsewhere. This article provides an overview of what is known about their location, characteristics, and symbolism, and discusses their contribution to understanding the Betä Ǝsraʾel polity.

1. Introduction: Church Construction in the Context of the Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic Wars

Throughout history, it has been common for political and religious leaders of given polities to erect religious structures and institutions affiliated with the polity’s dominant, official religion in territories that it had expanded into. Such establishments exemplified its dominion over the territories in question, served the populations affiliated with it which settled or were already present in these territories, and in some cases, encouraged and facilitated the spread of its official religion within them.1 Religious establishments, in general, serve a variety of purposes in addition to their role in facilitating worship. One role that some such establishments serve is that of commemoration—of specific events or individuals. In some cases, such establishments were built to commemorate military victories or conquests.2

Christianity, as a religion with roots partially stemming from the Jewish traditions prevalent at the time of its emergence, and which developed in constant interaction with Jews and Judaism in later times, was significantly engaged in defining itself vis-à-vis the latter and in polemics with the latter in different contexts and times.3 Concepts relating to Jews and Judaism are expressed in ecclesiastical architecture and art, and in traditions linked with specific ecclesiastical foundations.4 The overwhelming majority of such expressions developed in specific contexts of interaction between Christians and Jews, in which Jews were either subordinate to Christians, the two groups lived side by side as minorities, or Jews were largely absent.5

One mode of interaction between Christians and Jews—as two sovereign polities, engaged, at times, in military conflict—is extremely rare, but did occur. One example is the Late Antique kingdoms of Aksum (northern Ethiopia and Eritrea) and Ḥimyar (south-western Arabia), which converted to Christianity and Judaism, respectively, in the fourth century, and in the early sixth century were engaged in a military conflict which was portrayed as a conflict between Christianity and Judaism, and which culminated in the conquest of Ḥimyar by Aksum.6 A second example is the politically autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel7 (Ethiopian Jews) of the north-western Ethiopian Highlands, which were periodically tributary to and periodically in conflict with the Christian Solomonic kingdom, until their final subdual in 1626.

Given the complex dynamics between Christianity and Judaism, wars between sovereign Christians and Jews were perceived as bearing substantial theological significance. Both sides saw themselves as the true successors of the biblical Israelites and were aware of the competing claims put forth by the other side. Military victory was seen by the victors, at least in some cases, as demonstrating God’s favor.8 A church erected to commemorate Christian military victory over sovereign Jews could be endued with greater significance than that of “merely” a military victory over another religious group. It would validate ascendance over the religion which, more than any other, Christianity has been engaged with and defining itself in relation to from its emergence onward.

Both in the case of Ḥimyar and in the case of the sovereign Betä Ǝsraʾel, churches were erected following Christian military victories in the territories conquered.9 Some of the churches erected by Solomonic authorities in the territories conquered from the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel are explicitly mentioned in various sources as serving to commemorate specific Christian Solomonic victories over the Betä Ǝsraʾel. Such churches are a unique expression of Jewish–Christian interaction which has never before been examined in detail.

What do we know about such churches? Where and when were they built? Did they truly serve the commemorative role which they were reportedly assigned? How was this role expressed? Can these churches be located and examined?

In this article, I will examine textual and cartographical sources which shed light on churches built in the wake of Solomonic victories over the Betä Ǝsraʾel in territories conquered from the latter. I will examine the commemorative role of some of these churches and the significance of their location, and present the results of a first brief visit to the compound of one of them. I will demonstrate that the construction of these churches was a recurring event, suggest a methodology for locating them, and will argue that a wide-scale examination of such churches would shed unprecedented light on the scope of Betä Ǝsraʾel political autonomy in different times, on the sites of battles and Betä Ǝsraʾel strongholds, and on the Christianization process of territories formerly governed by the Betä Ǝsraʾel.

1.1. Research on the Betä Ǝsraʾel Polity and the Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic Wars

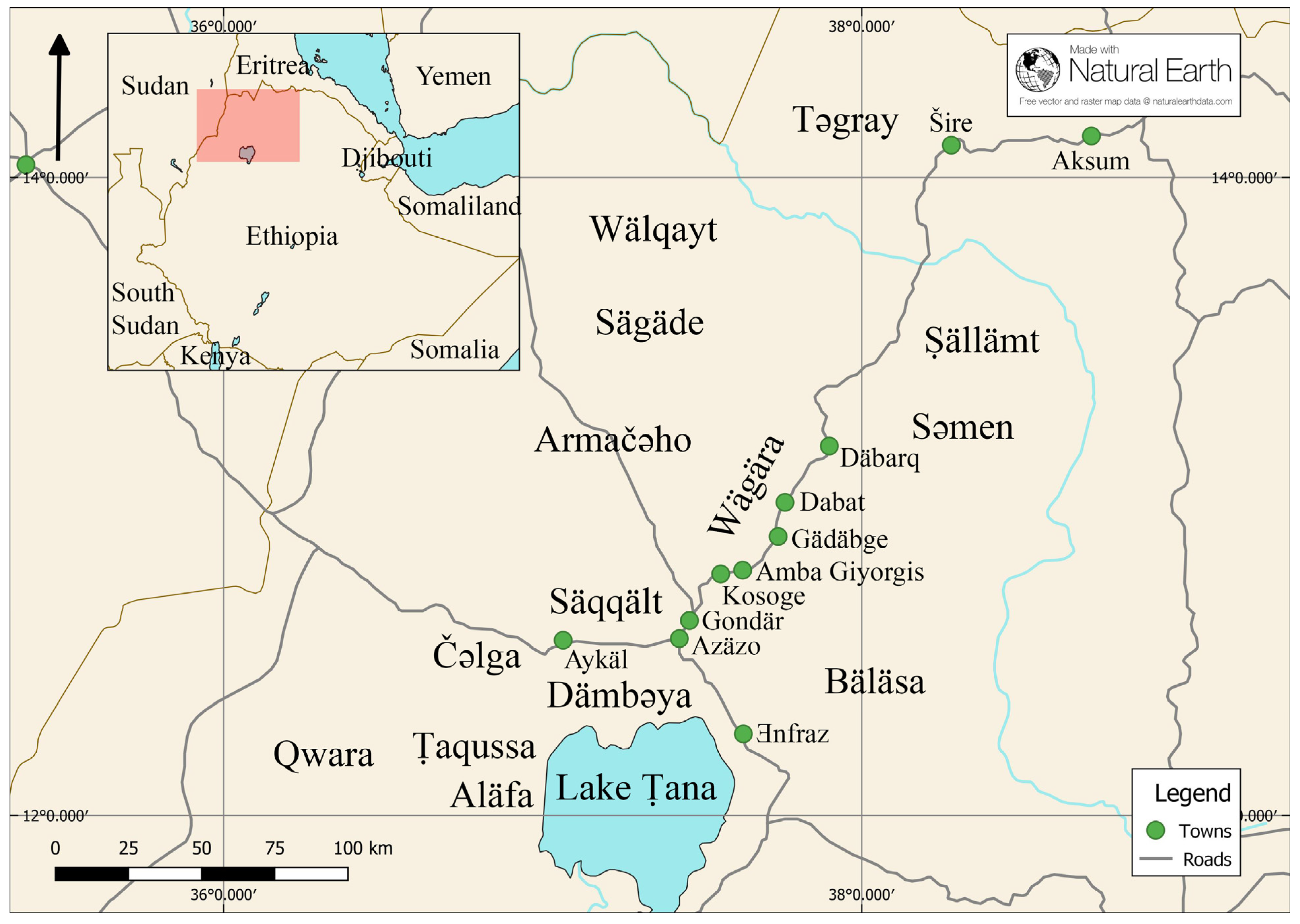

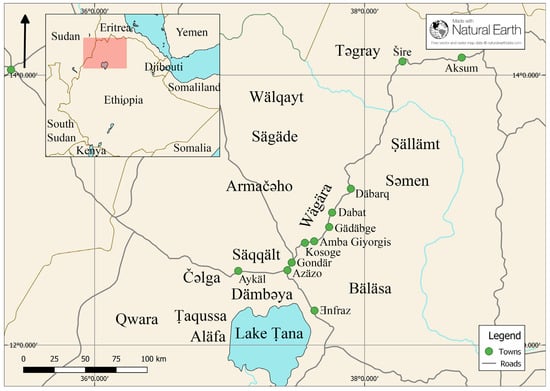

Following the rise to power of the Solomonic dynasty in 1270, the Solomonic kingdom, initially centered in the north-eastern Ethiopian Highlands and the adjacent Eritrean Highlands, gradually expanded its control to surrounding territories.10 Among these were the regions in the north-western Ethiopian Highlands inhabited by the Betä Ǝsraʾel (Figure 1). The consolidation of direct Solomonic rule in these regions was a gradual process. Up until the seventeenth century, the Betä Ǝsraʾel managed to maintain political autonomy in some of the territories they inhabited. The autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel were at times tributary to and at times at war with the Solomonic kingdom, and were significantly involved in its internal dynamics. As a result of Solomonic victories in wars against the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel, territories governed by the latter gradually came under direct Solomonic rule. Initially governing an extensive area extending from Ṣällämt in the north to Dämbəya in the south, by the time of the final subdual of the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel by the Solomonic emperor Susǝnyos (1607–1632) circa 1626, the area under their control was limited to the north-eastern Sǝmen Mountains (Kribus 2023; Kribus and Wexler, forthcoming).

Figure 1.

Main regions inhabited by the Betä Ǝsraʾel prior to their immigration to Israel.

Betä Ǝsraʾel political autonomy and the Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic wars have seen relatively little research. The studies of Steven Kaplan (1992, pp. 79–96) and James Quirin (1992, pp. 40–88), which examine Betä Ǝsraʾel history from its earliest attestation to the twentieth century, devote extensive chapters to this topic, with a focus on the historical processes underwent by the Betä Ǝsraʾel community at the time. Additional studies examine specific textual accounts which shed light on the Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic wars.11 Other than one article dealing, in part, with a sixteenth-century Betä Ǝsraʾel stronghold known in contemporary Portuguese sources as the “Mountain of the Jews”, written by Charles Fraser Beckingham (1951),12 specific sites associated with the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel had not, until recently, been pinpointed with precision or examined in research.

In recent years, I have conducted the first in-depth study of the historical geography of Betä Ǝsraʾel political autonomy and of the Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic wars, a central part of which is the identification of associated sites, including strongholds used by the Betä Ǝsraʾel and by their Solomonic opponents, and the examination of these sites, so far mainly through textual and cartographical sources and satellite imagery available online.13 Linked with this study is a study conducted by Sophia Dege-Müller and myself of a series of religious sites in the Sǝmen Mountains, which likely developed in dialogue with Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic dynamics in this region during and following Betä Ǝsraʾel autonomous rule (Kribus and Dege-Müller 2022; Dege-Müller and Kribus 2021). Additionally, a brief visit to the outskirts of a valley in the Sǝmen Mountains, which served as the seat of the leadership of the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel in the seventeenth century, was conducted together with Elad Wexler (Kribus and Wexler, forthcoming).

In the course of the above-mentioned research, I increasingly became aware of the phenomenon of church construction in the wake of Solomonic victories over the Betä Ǝsraʾel, and of the potential of these churches as sources shedding light on the historical geography of the Betä Ǝsraʾel polity. Three examples will be presented here, as well as additional churches which may have been linked with this phenomenon. Prior to that, in order to address this topic in context, we will briefly review the phenomenon of the construction of ecclesiastical foundations as an element linked with Solomonic expansion.

1.2. Church Construction in the Context of Solomonic Expansion

The areas under the control of the Solomonic kingdom from its onset to modern times were ethnically and religiously diverse, and included, in different regions and times, both territories governed directly by this kingdom and tributary territories, in which the regional nobility maintained a degree of autonomy (Deresse Ayenachew 2020). The Christianization of territories and the establishment of monasteries and churches within them played an important role in the consolidation of Solomonic rule. As demonstrated by Marie-Laure Derat (2003), the stark topography of the Ethiopian Highlands posed a challenge to centralized rule. One of the means of overcoming this challenge was supporting the development of a network of ecclesiastical institutions encompassing the territories under the king’s domain.

Pre-modern Solomonic Ethiopia was largely a rural society. In the absence of a significant number of urban centers, monasteries, in some cases, served as administrative centers of the rural population and could provide those in need with a degree of economic support. Ecclesiastical institutions were often endowed by Solomonic authorities with significant land grants, which could entail the right to collect taxes from the residents of the given lands, the responsibility of administering justice to them, as well as the right to collect revenues from markets and holy springs. Prior to the establishment of modern educational institutions in Ethiopia, Church schools were the only widespread educational institutions at the disposal of the country’s Christian population. Thus, the roles of ecclesiastical institutions vis-à-vis the general population were not limited to facilitating religious worship—they provided an array of services not necessarily provided directly by the Ethiopian Christian State.14

A key role in the Christianization of territories within the sphere of influence of the Solomonic kingdom was played by the monastic communities established within them. This could be through the initiative of or with the support of the monarchy and high-ranking ecclesiastical authorities (Derat 2003), but could also be independent of such support: as demonstrated by Steven Kaplan (1984, 1992, pp. 53–78), some monastic movements served as strongholds of regional traditions, in opposition to the centralizing policies of the Solomonic monarchy. Some such movements established monastic communities in areas peripheral to the Christian heartland and facilitated the spread of Ethiopian Christianity there. Disputes with central authorities were often temporary, and the resultant Christianization of these regions ultimately aided the consolidation of Solomonic rule within them.

Some ecclesiastical institutions enjoying royal patronage became the burial places of members of the Solomonic dynasty, and as a result assumed a commemorative role and greater affiliation with the dynasty. A commemorative role linked with specific Solomonic victories was, in some cases, established by depositing objects taken from vanquished enemies in a given church or monastery (Derat 2003). Significantly, this was practiced in the context of a military victory over the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel: in an account in a Tarikä Nägäśt compilation (see below) of the campaigns of the Solomonic monarch Śärṣä Dǝngǝl (r. 1563–1597) against the latter, it is related that this monarch “imprisoned Rädʾet [Rädaʾi, the leader of the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel] and exiled him to the Land of Wäǧ15 and he brought his horns and crowns to the Island of Daga.”16 The island of Daga on Lake Ṭana is the site of the monastery of Daga Ǝsṭifanos (Stephen), a monastery which occasionally enjoyed royal patronage and served as a burial place for members of the Solomonic dynasty (Bosc-Tiessé 2005).

It was customary for clergymen to accompany the Solomonic army and cater for the religious needs of the troops, as well as to establish churches in places where troops were stationed (Taddesse Tamrat 1972, p. 180). The need and the means to set up temporary churches in the context of campaigns was a matter of course. These means could also be utilized for the sake of commemorating a victory, as will be demonstrated below.

2. The Churches Constructed Following the Campaign of the Solomonic Monarch Yəsḥaq

The campaign of the Solomonic Monarch Yəsḥaq (r. 1414–1429/30) against the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel is one of the most significant turning points in the latter’s history: as a result of this campaign, the Betä Ǝsraʾel lost political control over the fertile plains of Wägära and Dämbəya, and in subsequent years, their autonomy was limited to the harsh, mountainous regions of Sǝmen and Ṣällämt. This campaign is described in two compilations of a literary genre which provides brief overviews of the reigns of several Ethiopian kings, known under the collective name Tarikä Nägäśt (History of Kings).17 It also features prominently in Betä Ǝsraʾel oral tradition and in the oral tradition of the residents of the region in which the campaign was held (Kaplan 1992, pp. 56–58; Quirin 1992, pp. 52–57; Kribus 2022). In a previous publication, I have examined this campaign and different sites associated with it, and have briefly mentioned the phenomenon of church construction in its aftermath and, specifically, the church of Yəsḥaq Däbr (Kribus 2023). Here, a detailed examination of this phenomenon and church will be provided.

The first, more detailed description of Aṣe18 Yəsḥaq’s campaign against the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel in a Tarikä Nägäśt compilation appears in a yet-unpublished paper manuscript, originally from Däbrä Ṣǝge Maryam monastery in the region of Šäwa. A digital version (EMML 7334) is available at the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library.19 The account relates that following Aṣe Yəsḥaq’s victory, he distributed land to his soldiers, and granted fiefs in the region of Wägära to various supporters, including a member of the Betä Ǝsraʾel ruling family who had supported him. Aṣe Yəsḥaq then decreed the following: “He who is baptized in the Christian baptism will inherit the land of his forefathers. Otherwise, he will be stripped of the land of his forefathers and be a fälase.” This decree, in the text, is followed by the statement: “And afterwards the Betä Ǝsraʾel were known as Fälašočč”.20 Finally, the account states the following: “And the king built many churches in the land of Dänbəya and Wägära.”21

The motif of church construction also appears in the second known Tarikä Nägäśt account of this campaign, contained in manuscript BnF, Éth. 142 of the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, which was published by René Basset.22 There, following a brief mention of the campaign, the following is written: “in his [Aṣe Yəsḥaq’s] days many churches were built in the land of Dämbəya and Wägära. In Kosoge there is the one called Yəsḥaq Däbr.”23 It is to this church, the most renowned of all churches built to commemorate Solomonic military victory over the Betä Ǝsraʾel, that we now turn.

2.1. The Church of Yəsḥaq Däbr

In my prior examination of Aṣe Yəsḥaq’s campaign (Kribus 2023), I argued, based on an analysis of the geography and road network of the region, as well as toponyms mentioned in relevant sources, that the church of Yəsḥaq Däbr was built on or near the battlefield of the decisive battle in which Aṣe Yəsḥaq defeated the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel. This hypothesis is supported by two sources which were committed to writing significantly later than the events they describe.

The first source is the account written by James Bruce, the famous Scottish traveler who travelled to Ethiopia in the years 1769–1771 and wrote extensively about the country’s history. When describing Aṣe Yəsḥaq’s campaign, Bruce (1790, vol.2, pp. 65–66) writes the following: “The king, coming upon the army of the Falasha in Woggora [Wägära], entirely defeated them at Kossogué, and, in memory thereof, built a church on the place, and called it Debra Isaac, which remains there to this day”.

This account closely follows the second Tarikä Nägäśt narration described above, but elaborates further on two points. The defeat of the Betä Ǝsraʾel was at Kosoge, and the church was built “in memory thereof” and “on the place”, presumably on the place where the defeat occurred. Bruce’s historiographic accounts are based in part on texts which he was able to consult in Ethiopia, including royal chronicles, and incorporate further details, some of which seem to be based on oral traditions he encountered. In the case at hand, it seems that these elaborations could be based on such oral traditions, or on his interpretation of the events as described in the Tarikä Nägäśt version known to us, or on a version of the written account currently not known, and which incorporates further details. Since oral traditions identifying the church of Yəsḥaq Däbr with the battle in question are still prevalent, as will be discussed below, I would argue that the first option is not unlikely.

A second source is the memoirs of Abba Yəsḥaq Iyasu, the high priest of the Betä Ǝsraʾel in the region of Təgray during the twentieth century. When providing a brief overview of Betä Ǝsraʾel history, Abba Yəsḥaq writes the following: “The emperor Yəsḥaq took control of the places where King Gideon24 had ruled, and from there began to spread Christianity, up to the place which is called Yəsḥaq Däbr” (Waldman 2018, p. 289). This account does not mention a church at Yəsḥaq Däbr, but does relate that the place played a role in spreading Christianity following the victory over the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel. It is more than likely that this account is indicative of Betä Ǝsraʾel oral tradition, and that the dedication of the church of Yəsḥaq Däbr to Solomonic victory over the Betä Ǝsraʾel was known to this community in modern times.

The commemorative role of the church may be alluded to by its name. Däbr, literally “mountain” in Geʿez,25 is a term which is often part of the name of Ethiopian Orthodox monastic churches. The allusion to a mountain does reflect the topographic reality of several monastic churches, but its usage is mainly symbolic as a reference to the sanctity of the site. Several churches designated as “Däbr” (Yəsḥaq Däbr being one of them) are not located on mountaintops (Kaplan 2005). “Yəsḥaq Däbr” literally means “Mountain of Yəsḥaq”, or “Monastic Church of Yəsḥaq”. Though the sources at hand relate that Aṣe Yəsḥaq founded several churches in the region, and though several churches in the region are indeed attributed to him, to the best of my knowledge, this is the only church which was chosen to be named after him. Thus, it must have been considered of special significance. Such significance would accord with it being the main church constructed to commemorate his victory, in which direct control of the surrounding regions was achieved. The full name of the church is Yəsḥaq Däbr Giyorgis, in reference to the saint to which it was dedicated, St. George. The significance of this dedication will be discussed below.

I briefly visited the church compound in January 2023. The interior of the church itself was, unfortunately, not accessible at the time. Following the visit, I examined the compound on Google Earth to ascertain its dimensions. I was accompanied on my visit by officials of the regional Culture and Tourism Bureau, who kindly provided information on the church.26

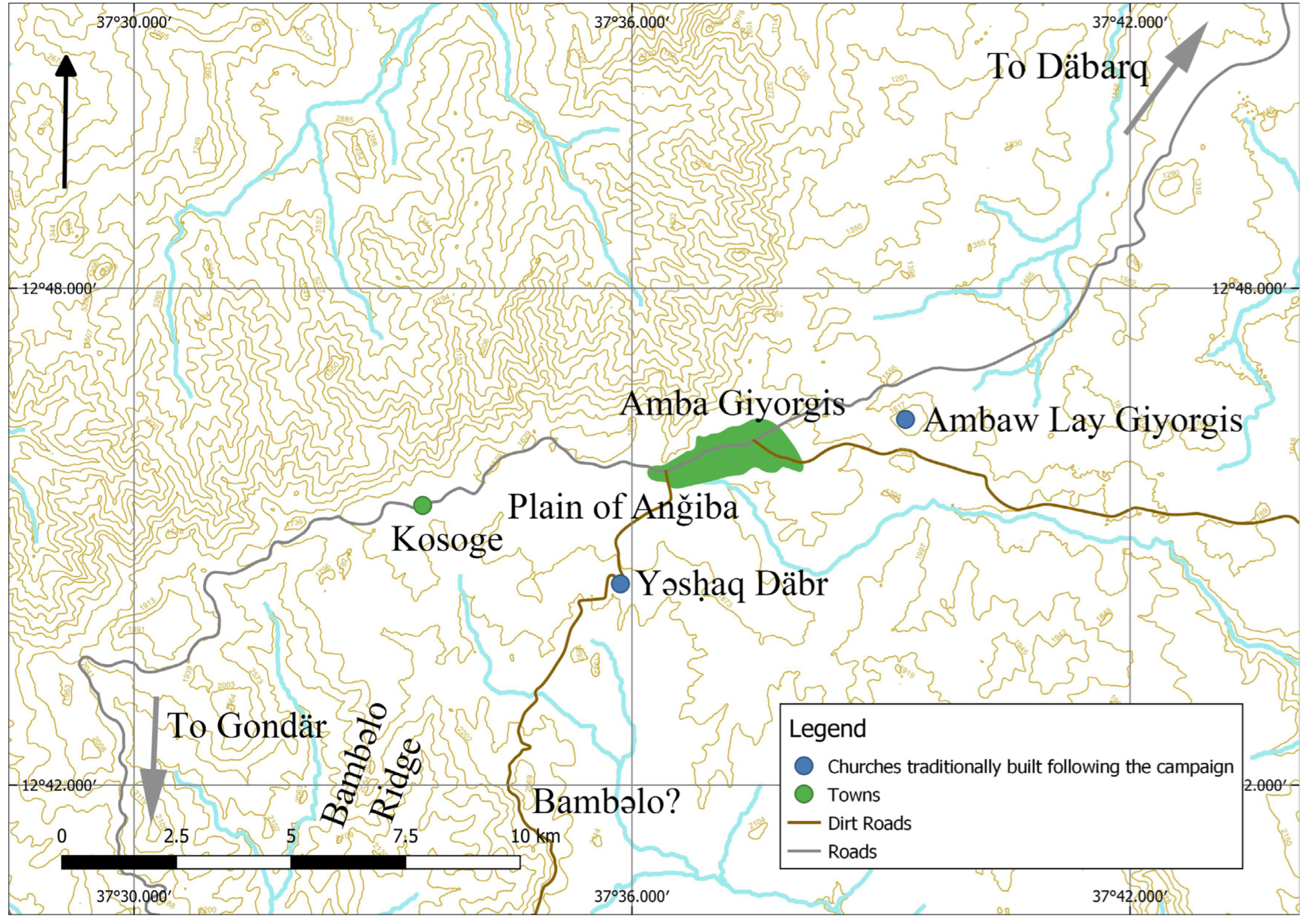

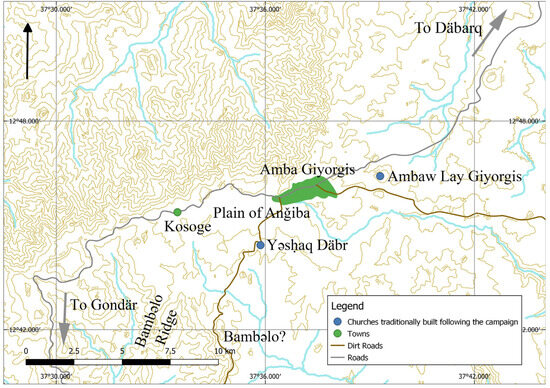

The church of Yəsḥaq Däbr (Figure 2) is located at the southern end of the Wägära Plateau, on a spur descending southwards to the upper tributaries of the Bir Mäsk stream.27 It is located 2.5 km south of the Gondär–Däbarq road, 4 km south-west of the center of the town of Amba Giyorgis, and 4.5 km east–south-east of the center of the village of Kosoge (Kosoye).28 A dirt road leads from the western end of Amba Giyorgis south-west towards the church, and continues to the south–south-west towards a locality labeled “Bambelo” on Google Earth (the name of the locality does not appear in other maps of the area examined).29 Just east of this locality is the ridge which, according to the Ambo Ber topographic map of the Ethiopian Mapping Authority (1998), is the Banbilo Ridge. It is more than likely that this is a rendering of the name Bambəlo, which is mentioned in the detailed Tarikä Nägäśt narration as the road which Aṣe Yəsḥaq travelled through to reach and engage with the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel in Wägära (Kribus 2023). It may be, therefore, that this dirt road was built along the historical route in question, since modern roads often make use of pre-existing routes, themselves shaped by topographical considerations still relevant in modern times. If so, Yəsḥaq Däbr would be located at the point where the “Bambəlo Road” reaches the heights of the Wägära Plateau, in which the battle was waged.

Figure 2.

Churches traditionally built following Aṣe Yəsḥaq’s victory over the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel in the vicinity of the modern town of Amba Giyorgis.

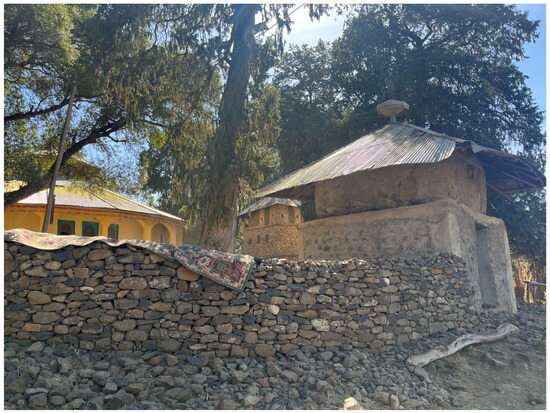

The church compound is located within a grove, which roughly forms two concentric rings, the exterior extending circa 160 m north–south and 170 m east–west, and the interior contained within the church compound and surrounding the church. The area extending from the eastern end of the compound to the eastern and south-eastern part of the exterior ring of trees is also forested.

The church compound is surrounded by a stone wall, enclosing an ovoid area extending circa 50 m north–south and 70 m east–west. South and west of the compound, contained within the exterior ring of trees, are structures which are most likely dwellings. At the western end of the compound is a gatehouse, measuring 7 m north–south and 7.5 m east–west (Figure 3). South of the gatehouse is a gap in the wall which enables access to the compound. The church, measuring 24 m east–west and north–south, is located at the center of the compound (Figure 4). A tower, measuring 5.5 m north–south and 6 m east–west, is located south-east of the gatehouse and south-west of the church (Figure 5). East of the church is an additional structure, the purpose of which is unknown to us.

Figure 3.

The enclosure wall of the Yəsḥaq Däbr church compound with the view to the south-east. The gatehouse is on the right, the tower can be seen above the wall in the center, and the church is on the left.

Figure 4.

The present-day church of Yəsḥaq Däbr with the view to the east.

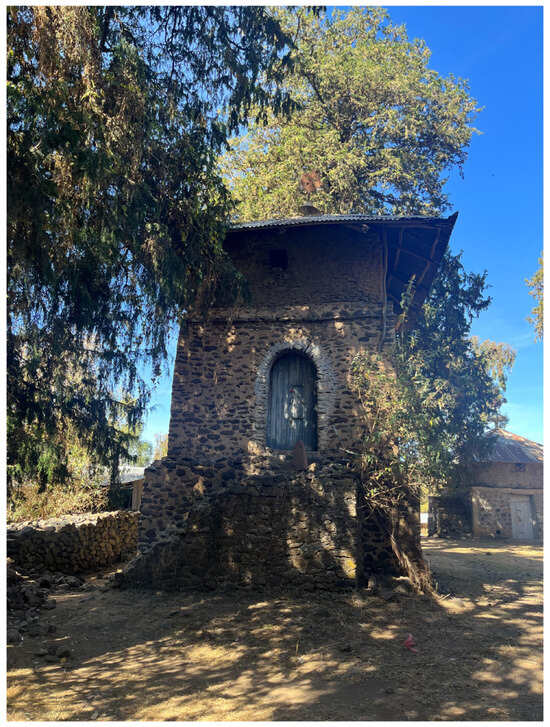

Figure 5.

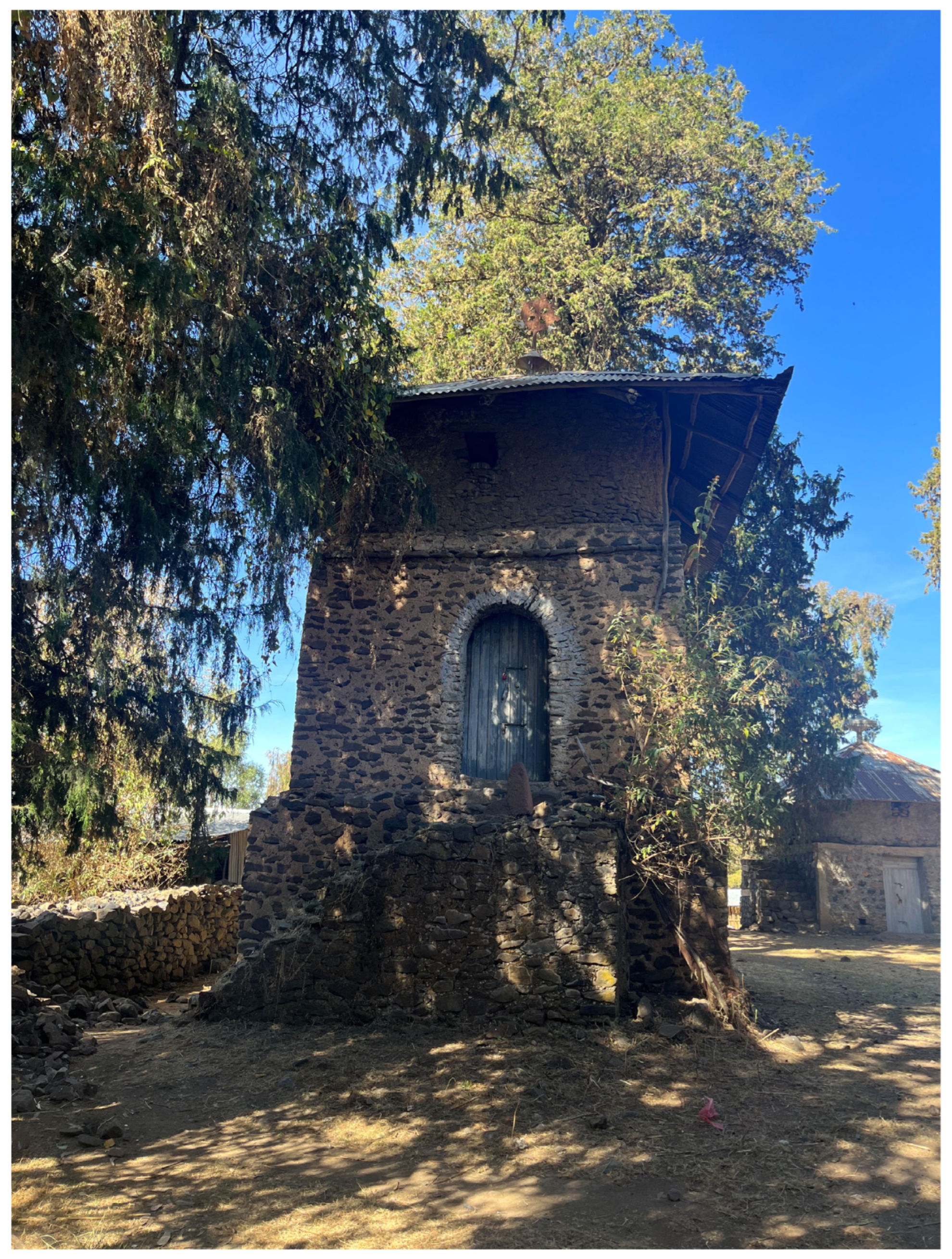

Tower attributed to the Solomonic emperor Yosṭos with the view to the west.

The church is of the concentric circular type, which is the main church type utilized in the north-western Ethiopian Highlands.30 The emergence of this church type is dated, based on its earliest known mentions in textual accounts, to the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century. This, together with the modern appearance of the present-day church structure, indicates that this structure post-dates Aṣe Yəsḥaq’s reign. And indeed, the officials of the Culture and Tourism Bureau accompanying us related that Aṣe Yəsḥaq had placed a metal cross on the site, later constructing a church there, following his victory over Gedewon (see fn 24),31 and that the church compound had been renovated three times. It seems, as is the case with other churches in the Ethiopian Highlands,32 that renovations post-dating the church’s foundation entailed reconstructing the church structure or its exterior.

The officials of the Culture and Tourism Bureau related that the tower within the church compound had been built by the Solomonic monarch Yosṭos (r. 1711–1716)33 in a manner similar to that of the castles at Gondär, and that originally, the tower was intended to be roofed by an egg-shaped dome (similar to the towers of the castle complex at Gondär). They added that the person in charge of the construction passed away before the dome could be built, and after a time in which the tower was open to the sky, a standard roof was constructed by the local community.34 The tower indeed incorporates elements typical of the Gondär architectural style, characteristic of compounds and structures constructed by the Solomonic monarchy from circa the late sixteenth century up to the eighteenth/nineteenth century (including the castles of Gondär).35 These elements include uncoursed walls constructed of basalt stones and lime mortar, an arched doorway, an external staircase, and a string course between the two stories (compare Figure 5 with Figure 6).36 The church of Narga Śǝllase (founded 1737–8, construction continued until 1750), for example, also incorporates square Gondär-style towers in its compound, roofed with an egg-shaped dome (Bosc-Tiessé 2007; di Salvo 1999, pp. 100–10).

Figure 6.

The castle of the Solomonic Monarch Fasilädäs (1632–1667) in Gondär, built in accordance with the Gondär architectural style.

2.2. The Church of Ambaw Lay Giyorgis

The officials of the Culture and Tourism Bureau related that Yəsḥaq Däbr was the first place in the area that Aṣe Yəsḥaq reached and the first church he constructed there, but that he had constructed additional churches in the area, the second one being the church of Ambaw Lay Giyorgis (literally “[the Church of] St. George on the Mountaintop”),37 which the town of Amba Giyorgis is named after.38 We viewed the hill on which the church is built from a vantage point along a dirt road leading eastwards from Amba Giyorgis (Figure 7), but the time at hand did not enable a visit to the church. An examination of the church on Google Earth reveals that it is located on the summit of the hill, and is of the concentric circular type, measuring 21 m north–south and east–west. Similar to Yəsḥaq Däbr, it is surrounded by a grove comprising an exterior ring of trees, measuring 210 m north–south and 205 m east–west, and an interior ring surrounds the church, measuring 100 m north–south and 105 m east–west. Structures are built to the north and to the south-east of the church. It is likely that the church is surrounded by an elliptical enclosure wall (judging from the shape of the interior ring of the grove and the alignment of the structures north of the church), but this cannot be ascertained on Google Earth. It would seem that in this case as well, if indeed the church was initially constructed by Aṣe Yəsḥaq, the current church structure was probably constructed at a later time.

Figure 7.

The hill on the summit of which the church of Ambaw Lay Giyorgis is located, with the view to the east–north-east.

2.3. Additional Churches Attributed to Aṣe Yəsḥaq

The people from the Culture and Tourism Bureau mentioned an additional church traditionally founded by Aṣe Yəsḥaq in the region, in a locality by the name of Bəra, which I have not yet been able to locate. Local oral tradition recognizes other churches in the region as being founded by Aṣe Yəsḥaq, many of them dedicated to Qəddus Giyorgis (St. George). One example is the church of Abwara Giyorgis in Gondär.39 Assuming that this tradition is indeed indicative of Aṣe Yəsḥaq’s time, it is unknown why such a dedication to Qəddus Giyorgis would be chosen as the standard dedication. It does stand to reason that this saint’s role as a warrior saint would have been appealing and may have been seen as fitting for the context of churches constructed following a successful military campaign.40

3. Churches Erected on Conquered Betä Ǝsraʾel Strongholds During the Campaigns of the Solomonic Monarch Śärṣä Dǝngǝl

A second, fascinating example of churches constructed to commemorate Solomonic victories over the Betä Ǝsraʾel is related in the royal chronicle of the Solomonic monarch Śärṣä Dǝngǝl (r. 1563–1597), a text written during the reign of this king and which incorporates eyewitness accounts (Solomon Gebreyes Beyene 2019, 2023). This monarch waged either two or three campaigns against the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel in the Sǝmen Mountains.41 During the first campaign, waged in 1579, his main opponent was Rädaʾi, the leader of the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel. When the Solomonic army reached Rädaʾi’s main stronghold, following an initial military confrontation, Rädaʾi surrendered, and Solomonic forces took control of it (Conti Rossini 1907, pp. 91–95). The Solomonic army then erected a church tent on the stronghold:

On that Friday, Abba Nǝway [one of the Solomonic commanders who was also a clergyman] ascended the amba carrying a däbäna [royal tent] with the tabot42 of Our Lord Jesus and with the holy items with which the mass is celebrated. And he brought with him for this church singers of religious chants [mäzämran] and priests, for they are always ready to hold a sacrifice, like the children of Aaron. And the reason of this ascent to hold mass on this amba is so that they would sanctify this place, which the pigs had defiled and where wild animals grazed, with the mass. And on Sunday, the king, together with many soldiers, climbed that mountain and came to that church, and attended the mass, praising God in this place, where the name of Our Lady Mary was not called, now serving as a place of sacrifice of the flesh and blood of the Son of God who was made man by the Holy Spirit and from Mary, from the Holy Virgin. A second reason for holding mass on this amba: It is said, to sustain the memory [täzkar] of this thing and so that the account will remain from generation to generation. Fathers will tell their children. The children that will be born and grow will tell their children so that they will place their trust in God. And so they do not forget the deeds of God and his miracles which took place in this amba.

On this day, ʿAsbe [one of the clergymen accompanying the Solomonic army] sangʿeṭanä mogär43 to commemorate the victory of this Christian king and the defeat of this accursed Jew. For such is the custom of the priests of Ethiopia, to sing in the churches hymns which recall the exploits of the king of the time.44

This fascinating description explicitly describes the purpose of the church erected. The language used is polemical—though the site was the main stronghold of the leader of the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel, and hence, hardly a desolate place, the mass was held “so that they would sanctify this place, which the pigs had defiled and where wild animals grazed”. The mass is explicitly presented as a victory of Christianity: “praising God in this place, where the name of Our Lady Mary was not called, now serving as a place of sacrifice of the flesh and blood of the Son of God”. And finally, though the church was, at the time, a church tent (likely erected as such so that mass could be held within a short time), the description implies that the site would serve to commemorate victory for years to come: “to sustain the memory of this thing and so that the account will remain from generation to generation […] And so they do not forget the deeds of God and his miracles which took place in this amba.”

A second example of the erection of a church tent on a conquered Betä Ǝsraʾel stronghold is mentioned in the chronicle, in the context of Śärṣä Dǝngǝl’s campaign against the Betä Ǝsraʾel leader Gwäšǝn in 1587. After conquering the Betä Ǝsraʾel stronghold of Wärq Amba, and after Gwäšǝn and many of his men had flung themselves off a cliff rather than be taken captive (Conti Rossini 1907, pp. 102–10), a church tent was erected on the amba and mass was held there:

The king decided that an offering of thanksgiving would be given to the Lord. He called the head [priests] and the cantors and commanded them to go to that amba and offer there a pure sacrifice—eloquent incense and a spiritual offering in thanksgiving to the Lord, who brought victory in that amba, the height of which is likened to reaching the sky. […] The priests who were commanded to do so climbed up the amba, pitched the däbäna [royal tent] and drew curtains as is befitting the rite of the offering. And when they had finished mass, they received the Sacred Mysteries. And afterwards the priests sang hymns of thanks, recalling the victory of the king.45

In this case, there is no explicit mention of long-term commemoration of the victory at the site. As stated above, it is not clear whether a more permanent church structure was erected on either stronghold. Nevertheless, the mention of churches erected on two Betä Ǝsraʾel strongholds following their conquest is noteworthy and seems to indicate that this method—the erection of a church on a vanquished Betä Ǝsraʾel stronghold as a symbol of victory over the Betä Ǝsraʾel—was an integral part of Śärṣä Dǝngǝl’s strategy.

4. Conclusions

As demonstrated in this study, the erection of churches, both to commemorate and exemplify Solomonic victories against the Betä Ǝsraʾel and to facilitate the Christianization of regions and localities conquered from them, was an integral part of Solomonic policy in the Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic wars, at least during the reigns of the Solomonic monarchs Yəsḥaq and Śärṣä Dǝngǝl. While the construction of churches by a Christian polity in the wake of victory over non-Christians is by no means unusual, the fact that these specific churches were constructed to commemorate Christian military victory over Jews makes them unique and endows them with an added layer of symbolism. At least in the case of Yəsḥaq Däbr, the symbolic role of the church has persisted to the present day, and is reflected in the present-day oral traditions of both the Ethiopian Orthodox residents of the region and of the Betä Ǝsraʾel.

That the conflict between the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel and the Christian Solomonic kingdom included religious overtones, with each group attempting to demonstrate its being the heir of biblical Israel, is indicated in Śärṣä Dǝngǝl’s chronicle: Rädaʾi, the Betä Ǝsraʾel leader, reportedly named different mountains in his domain after mountains mentioned in the Bible, an action which the chronicler rebukes as the audacity to compare his land with that of biblical Israel (Conti Rossini 1907, p. 99). Śärṣä Dǝngǝl, in turn, after having conquered Rädaʾi’s stronghold and while still in the Səmen Mountains, appointed himself as head ecclesiastic of the church of Maryam Ṣǝyon in Aksum, which symbolizes, in the eyes of Ethiopian Orthodox Christians, Christian Ethiopia’s theological status as the heir of biblical Israel.46 Thus, the battle was waged, so to speak, not only in the physical realm, but also in the religious–ideological one. In this context, the symbolic value of erecting churches on sites of Betä Ǝsraʾel strongholds is clear.

The churches commemorating Solomonic victories over the Betä Ǝsraʾel have never been examined in situ in scholarship (with the exception of my brief visit to Yəsḥaq Däbr). Such an examination would shed valuable light on numerous aspects relating to Betä Ǝsraʾel political autonomy and the Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic wars: it is more than likely that elements in the architecture and art of these churches would be in dialogue with the events that they commemorate, and this is certainly the case with regards to the oral traditions associated with them.

A first, vital step would be to securely date both the initial foundation of the churches and the present-day structures in their compounds, based on architectural remains and textual and artistic evidence. With regards to the church structures of Yəsḥaq Däbr and Ambaw Lay Giyorgis, it seems more than likely that these significantly post-date Aṣe Yəsḥaq’s time, but this does not necessarily hold true for all art and artifacts within the church compounds. And even if no physical remains of the original church compound survive, an examination of such churches and their associated oral traditions would nevertheless shed significant light on Christian engagement with the concept of victory over the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel in later times.

Accurately pinpointing churches which were established in the wake of Solomonic victories against the Betä Ǝsraʾel would contribute to our understanding of the geography of Betä Ǝsraʾel political autonomy: locating Aṣe Yəsḥaq’s establishments in Wägära and Dämbəya would serve as a likely indication of the geographical scope of the territories conquered from the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel (within which it stands to reason that many of these churches would be built).47 The precise locations of Rädaʾi and Gwäšǝn’s strongholds are currently not known.48 It may be, if permanent church structures were indeed constructed on them and if such churches indeed persisted over time, that it would be possible to identify the strongholds by locating these churches. And it may also be (though this remains to be determined) that churches were constructed over additional Betä Ǝsraʾel strongholds and could contribute to the identification of such strongholds.

Sites, and especially religious sites, can serve as anchors of memory and expressions of interreligious interaction, that in some cases persist (albeit not unchanged) for extensive periods of time. In the north-western Ethiopian Highlands, numerous such sites remain unexplored and undocumented. It is my hope that future exploration will further illuminate the fascinating history of this region, of the religious groups residing in it, and of the interactions between them.

Funding

The possibility to devote myself to this research and funding for a visit to Ethiopia were provided the Dan David Society of Fellows, Tel Aviv University. This research builds upon my past research, which was supported by the ERC Project JewsEast (funded by the European Research Council within the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovative program, grant agreement no. 647467, Consolidator Grant JewsEast), the Minerva Stiftung Gesellschaft für die Forschung mbH, the Ethiopian Jewry Heritage Center, the Ben-Zvi Institute for the Study of Jewish Communities in the East, the Ruth Amiran Fund for Archaeological Research in Eretz-Israel, the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel School for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University and the Center for the Study of Christianity at the Hebrew University.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | There are numerous examples of this phenomenon in polities affiliated with different religions. See, for example, (Boas 2001, pp. 102–33; Cytryn 2009; Guidetti 2016; Pogossian 2017). |

| 2 | See, for example, (Leisten 1996; Becket 2014). |

| 3 | See, for example, (Diprose 2000; Fredriksen and Irshai 2006; Becker and Reed 2007). |

| 4 | See, for example, (Revel-Neher 1992; Faü 2005; Lipton 2014; Kribus et al. 2024). |

| 5 | For a discussion on the significance of examining Jewish–Christian interactions in diverse contexts, see (Cuffel and Gamliel 2018). |

| 6 | There is extensive literature on this topic. See, for example, (Munro-Hay 1991; Robin 2004; Gajda 2009; Beaucamp et al. 2010; Phillipson 2012; Bowersock 2013). |

| 7 | The transcription system of the Encyclopaedia Aethiopica will be used in this article for terms in Amharic and Geʿez. |

| 8 | For a discussion of this theme in relation to the Aksumie–Ḥimyarit war, see (Bowersock 2013, pp. 78–105; Piovanelli 2013, pp. 22–24). For examples relating to Ethiopian Orthodox Christians, the Betä Ǝsraʾel and the dynamics between them, see (Abbink 1990; Kaplan 1992, p. 87; Kribus 2022). The concept of Ethiopian Orthodox Christians as not only inheritors of divine promise, but as de facto Israelites, is one of the main themes of the Kǝbrä Nägäśt (Glory of Kings), a work compiled in the fourteenth century based on earlier material, and commonly considered the national epic of Christian Ethiopia (Marrassini 2007; HaCohen 2009). |

| 9 | For examples relating to Ḥimyar, see (Moberg 1924, p. cxlii; Detoraki and Beaucamp 2007, p. 282; Bowersock 2013, pp. 103–4). Examples relating to the Betä Ǝsraʾel will be discussed throughout this article. |

| 10 | See, for example, (Taddesse Tamrat 1972; Kaplan 2011; Deresse Ayenachew 2020). |

| 11 | See, for example, (Halévy 1907; Waldman 1989; Corinaldi 2005; David 2023). |

| 12 | For an updated examination of the location and characteristics of this stronghold, based on geographical information not accessible to Beckingham at the time, see (Kribus, forthcoming a). |

| 13 | (Kribus 2023; forthcoming b; forthcoming c). Fieldwork aimed at reaching and systematically surveying these sites has so far not been possible, first due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and then due to political unrest in the respective area. It is my hope to embark on such fieldwork once the regions in question become safe and accessible. |

| 14 | For an overview of Ethiopian ecclesiastical institutions and their roles with regards to lay society, see (Chaillot 2002; Kaplan 2007; Isaac 2013; Binns 2017). |

| 15 | The region of Wäǧ is located in Šäwa, south of the Mugär River. See (Solomon Gebreyes Beyene 2015, pp. 109, 113). |

| 16 | (Perruchon 1896, pp. 180–81), my translation. The Geʿez text reads: “ዓሰሮ ፡ ለበረድኤት ፡ ወአግዓዞ ፡ በምድር ፡ ወጅ ፡ ወወሀበ ፡ አቅርንቲሁ ፡ ወአክሊላቲሁ ፡ ለደሴተ ፡ ዳጋ ።”. |

| 17 | The earliest known version of a Tarikä Nägäśt compilation was composed in the sixteenth century, as an introduction to the royal chronicle of the Solomonic monarch Śärṣä Dǝngǝl (Solomon Gebreyes Beyene 2016, pp. 64–65). The composition and chronology of Tarikä Nägäśt compilations vary considerably, and often, local and regional considerations had an impact on their content. The eclectic nature of these compilations, and the uncertain provenance of much of their source material, has posed a challenge to dating the accounts contained within them. For published examples of such compilations, see (Beguinot 1901; Foti 1941; Dombrowski 1983). |

| 18 | Aṣe is a royal title, and was commonly used in the Solomonic period to refer to Solomonic monarchs. |

| 19 | The date of composition of the account is unknown, and it is clear that the manuscript significantly post-dates the events it describes. For a discussion on this manuscript, see (Dege-Müller 2020, p. 57). A summary of the account is provided by Taddesse Tamrat (1972, pp. 200–1). For a detailed overview of this account and the translations of various sections, see (Kribus 2023). |

| 20 | EMML_7334_032, translated by the present author. The term Fälaša (Falasha) was widely used to refer to the Betä Ǝsraʾel prior to the second half of the twentieth century, and probably no earlier than the fifteenth century. At present, it is considered derogatory and rarely used. Different meanings were attributed to this term (for an overview on this topic and on terms used to refer to the Betä Ǝsraʾel, see (Kaplan 1992, pp. 65–73; Salamon 1999, pp. 21–23). In the context of the above-mentioned account, the term is used in reference to the landless status of the group in question. The Geʿez text reads: “ዘተጠምቀ ፡ ጥምቀተ ፡ ክርስትና ፡ ይረስ ፡ ርስተ ፡ አቡሁ ፡ ወእመ ፡ አኮሰ ፡ ይትመሀው ፡ እምርስተ ፡ አቡሁ ፡ ወይኩን ፡ ፈላሴ ፡ ወእምድኀሬሁ ፡ ተሰምዩ ፡ ቤተ ፡ እስራኤል ፡ ፈላሾች”. The word ቤተ (Betä) is written above the line and thus is an addition or correction. The translation without this word would read: “And afterwards the Israelites were known as Fälašočč”. |

| 21 | EMML_7334_032, translated by the present author. The Geʿez text reads: “ወሐንፀ ፡ ንጉሥ ፡ አብያተ ፡ ክርስቲያናት ፡ ብዙኀት ፡ በምድረ ፡ ደንብያ ፡ ወወገራ”. |

| 22 | (Basset 1881, p. 95; 1882, pp. 11–12). The text in question ends with the death of the Solomonic monarch Bäkaffa (r. 1721–1730). Basset (1882, pp. 5–6) therefore suggests that it was compiled in the days of his son and successor, Iyasu II (r. 1730–1755). |

| 23 | The Geʿez text reads: “ወበመዋዕሊሁ ፡ ተሐንፃ ፡ ብዙኃት ፡ አብያተ ፡ ክርስቲያናት ፡ በምድር ፡ ደምብያ ፡ ወወገራ ፤ በኮሶጌሃ ፡ ሀሎ ፡ ዘይሰመይ ፡ ይስሐቅ ፡ ደብር ።” |

| 24 | According to Betä Ǝsraʾel tradition, they were ruled by a dynasty of seven or nine kings, all named Gedewon (the Amharic and Geʿez version of the name Gideon). And indeed, a Betä Ǝsraʾel leader by that name plays a central role in the accounts of the Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic wars which took place during the reign of Śärṣä Dǝngǝl (Conti Rossini 1907, p. 123, 170–71; Solomon Gebreyes Beyene 2023) and Susǝnyos (Pereira 1900, pp. 116–18, 136, 209, 215–18, 387, 437, 441, 464, 553). Letters written by Rabbi Abraham ha-Levi in Jerusalem in 1525 and 1528 mention Betä Ǝsraʾel rulers named “Gad and Dan”, which seem to be a rendering of Gedewon (Waldman 1989, pp. 58–64). The Betä Ǝsraʾel tradition of a dynasty of kings bearing the name Gedewon is mentioned in several accounts written by Westerners who came in contact with members of this community, including James Bruce (1790, vol. 1, pp. 486, 526; vol. 2, pp. 165, 289–93; vol. 3, pp. 252, 286). It has been suggested that this name served as a regnal name (Quirin 2005). |

| 25 | Geʿez was the official language of the Late Antique kingdom of Aksum, the predecessor of medieval and modern Christian Ethiopia. This language subsequently became the liturgical language of both Ethiopian Orthodox Christians and of the Betä Ǝsraʾel, and the language commonly utilized for textual compositions in Christian-ruled Ethiopia prior to the twentieth century (much like Latin in Western Europe). See (Weninger 2005). |

| 26 | I wish to express my sincere thanks to the Culture and Tourism Bureau for enabling the visit and for the information provided. |

| 27 | In the Ambo Ber topographic map produced by the Ethiopian Mapping Authority (1998), the name of the stream is spelled “Bir Mesk”. It is likely that this name should be transcribed as Bir Mäsk, but this spelling will have to be verified in future field trips. |

| 28 | The suffix “ge” appears in numerous place-names in Wägära and Səmen and denotes a locality. In the colloquial pronunciation of such place-names, “ge” is often substituted with “iya” or “ye”. Though the name “Kosoge” is the official name of the locality, it is commonly pronounced “Kosoye”. |

| 29 | It should be taken into account that the appearance of this name on Google Earth is not clear-cut proof that this is indeed the name of the locality. The name in question should be verified in future fieldwork. Since this locality is adjacent to a ridge bearing the same name (see below), I would argue that it is not unlikely that it bears this name. |

| 30 | For an overview on this church type, its layout, chronology, and sources of inspiration, see (di Salvo 1999; Heldman 2003; Fritsch 2018; Kribus 2024). |

| 31 | The information provided by the officials provides insight on how the church in question and other associated sites are presently remembered. The fact that Yəsḥaq Däbr is attested to have been conceptually linked with Aṣe Yəsḥaq’s campaign at different times demonstrates the longevity of this concept. |

| 32 | See, for example, (Pankhurst 2005; Phillipson 2009, pp. 82–84). |

| 33 | For an overview on this monarch, see (Crummy 2014). |

| 34 | The officials did not relate their source of information, and I would assume that it is based either on local oral tradition or on textual accounts unknown to me. |

| 35 | Gondär-style architecture was utilized in the construction of palaces, churches, and bridges. Its features include uncoursed walls constructed of rough stones and lime mortar, monumental entrance gates, arched doors and windows, barrel vaulting, and round corner towers roofed by domes (Berry 1995, 2005). |

| 36 | While the corner towers apparent in Figure 6 are round, observation towers built in accordance with this style are typically square (Berry 1995, pp. 7–8), and thus accord with the tower at Yəsḥaq Däbr. |

| 37 | The Amharic and Geʿez term amba can refer either to a fort or stronghold, or to a mountaintop (most notably a table mountain). It can also be used as a place-name, regardless of the topography of the place in question. |

| 38 | Here, again, the comment is indicative of how the church is remembered. It is my hope that future exploration will shed more light on the chronology of this church. |

| 39 | Personal communication with Sisay Sahile and Sophia Dege-Müller. I would like to express my sincere thanks to both of them for providing me with this information. |

| 40 | That Qəddus Giyorgis may have been an appealing saint for Aṣe Yəsḥaq due to his being a warrior saint was pointed out to me by Tadele Molla Tagegne. I would like to thank him for his continuous help, support, and insight in our research on sites related to the Betä Ǝsraʾel in Ethiopia. |

| 41 | Two campaigns are mentioned in his royal chronicle (Conti Rossini 1907, pp. 85–111), and three in an overview of his reign appearing in Tarikä Nägäśt compilations (Perruchon 1896, pp. 180–81). It has been suggested in scholarship that either Śärṣä Dǝngǝl’s chronicle groups together the first two campaigns, presenting them as one (Kaplan 1992, pp. 86–88), or that the second campaign is not mentioned in the chronicle (Quirin 1992, pp. 78–79). |

| 42 | A tabot is the altar-tablet upon which the Eucharist is held in Ethiopian Orthodox churches. It is consecrated, and bears a dedication which commonly gives its name to the church in which it is kept. The tabot is considered the most sanctified object in a church, and symbolically embodies it. It bears the symbolism of the biblical Ark of the Covenant and the Tablets of the Law (Heldman 2011). |

| 43 | The verb used here to denote singing, täqänyä, can also refer specifically to the composition of qəne, a genre of Geʿez literature, comprising hymns expressing praise and thanksgiving, improvised by däbtära (cantors) during the liturgy (Leslau 1991, p. 437). ʿEṭanä mogär is a type of qəne sung during the liturgy (Habtemichael Kidane 2011). |

| 44 | (Conti Rossini 1907, p. 95), my translation. The Geʿez text reads: ዘውእቱ ፡ ዕለተ ፡ ዓርብ ፡ ዓርገ ፡ አባ ፡ ንዋይ ፡ መልዕልተ ፡ ውእቱ ፡ አምባ ፡ ነሢኦ ፡ ደበና ፡ ምስለ ፡ ታቦት ፡ እግዚእነ ፡ ኢየሱስ ፡ ወምስለ ፡ ንዋየ ፡ ቅድሳት ፡ ዘየዓርጉ ፡ ቦቱ ፡ ቍርባነ ። ወነሥኦሙ ፡ ምስሌሁ ፡ ለመዘምራን ፡ ወለካህናተ ፡ ውእቱ ፡ ቤተ ፡ ክርስቲያን ፡ እስመ ፡ ሥሩዓት ፡ ዘልፈ ፡ እሙንቱ ፡ ለግብረ ፡ ምሥዋዕ ፡ ከመ ፡ ደቂቀ ፡ አሮን ። ወምክንያቱሰ ፡ ለዝንቱ ፡ አዕርጎተ ፡ ቍርባን ፡ በውእቱ ፡ አምባ ፡ ከመ ፡ ይቀድሱ ፡ ቍርባን ፡ ይእተ ፡ መካን ፡ ዘአርኰሳ ፡ ሐራውያ ፡ ወተርእያ ፡ እንሰሳ ፡ ገዳም ። ወበዕለተ ፡ እሑድ ፡ ዓርገ ፡ ዝንቱ ፡ ንጉሥ ፡ መልዕልተ ፡ ውእቱ ፡ ደብር ፡ ምስለ ፡ ብዙኃን ፡ ሠራዊት ፡ ወቦአ ፡ ኀበ ፡ ይእቲ ፡ ቤተ ፡ ክርስቲያን ፡ ወአቅረበ ፡ መሥዋዕተ ፡ አኰቴት ፡ ለእግዚአብሔር ፡ በመካን ፡ ዘኢይጼውዑ ፡ ቦቱ ፡ ስመ ፡ እግዝእትነ ፡ ማርያም ፡ ዘረሰያ ፡ ምሥዋዓ ፡ ሥጋሁ ፡ ወደሙ ፡ ለወልደ ፡ እግዚአብሔር ፡ ዘተሰብአ ፡ እመንፈስ ፡ ቅዱስ፡ ወእማርያም፡ እምቅድስት ፡ ድንግል ። ካልእኒ ፡ ምክንያት ፡ በእንተ ፡ አዕርጎተ ፡ ቍርባን ፡ ዲበ ፡ ዝንቱ ፡ አምባ ። ተብሀለ ፡ ከመ ፡ ይኩን ፡ ተዝካረ ፡ ነገር ፡ ወከመ ፡ ይትርፍ ፡ ዜና ፡ ለትውልደ ፡ ትውልድ ፡ ዘይመጽእ ። አበውኒ ፡ ከመ ፡ ይዜንዉ ፡ ለደቂቆሙ ፡ ደቂቅኒ ፡ እለ ፡ ይትወለዱ ፡ ወይትነሥኡ ፡ ይዜንዉ ፡ ለደቂቆሙ ፡ ወከመ ፡ የረስዩ ፡ ትውክልቶሙ ፡ ላዕለ ፡ እግዚአብሔር ፡ ወከመ ፡ ኢይርስዑ ፡ ግብረ ፡ እግዚአብሔር ፡ ወተአምሪሁ ፡ ዘኮነ ፡ በዝንቱ ፡ አምባ ። በይእቲ ፡ ዕለት ፡ ተቀንየ ፡ ዓስቤ ፡ ዕጣነ ፡ ሞገር ፡ እንዘ ፡ ያዜክር ፡ መዊኦተ ፡ ዝንቱ ፡ ንጉሥ ፡ መሲሐዊ ፡ ወተመውኦ ፡ ዝኩ ፡ ርጉም ፡ አይሁዳዊ ። እስመ ፡ ከመዝ ፡ ልማዶሙ ፡ ለካህናተ ፡ ኢትዮጵያ ፡ የሀልዩ ፡ በቤተ ፡ ክርስቲያን ፡ ማኅሌተ ፡ ድርሳን ፡ እንዘ ፡ ያዜክሩ ፡ ትሩፋተ ፡ ንጉሥ ፡ ዘኮነ ፡ በዘመኑ ።. |

| 45 | (Conti Rossini 1907, pp. 110–11), my translation. The Geʿez text reads: መከረ ፡ ዝንቱ ፡ ንጉሥ ፡ ከመ ፡ ያዕርግ ፡ መሥዋዕተ ፡ አኰቴት ፡ ለእግዚአብሔር ። ወእምዝ ፡ ጸውዓ ፡ ሊቃውንተ ፡ ወመዘምራነ ፡ ወአዘዞሙ ፡ ከመ ፡ ይሖሩ ፡ ኀበ ፡ ውእቱ ፡ አምባ ፡ ወያዕርጉ ፡ በህየ ፡ ቍርባነ ፡ ንጹሐ ፡ ዕጣነ ፡ ነባቤ ፡ ወመሥዋዕተ ፡ መንፈሳዌ ፡ ለአኰቴተ ፡ እግዚአብሔር ፡ ዘወሀበ ፡ መዊአ ፡ በዝንቱ ፡ አምባ ፡ ዘኑኀተ ፡ ቆሙ ፡ ይመስል ፡ ውስተ ፡ ሰማይ ፡ ዘይበጽሕ [...] ካህናትሰ ፡ እለ ፡ ተአዘዙ ፡ ዓርጉ ፡ ኀበ ፡ ውእቱ ፡ አምባ ፡ ተከሉ ፡ ደበና ፡ ወአንጦልዑ ፡ መንጠዋልዓ ፡ በከመ ፡ ይደሉ ፡ ለሥርዓተ ፡ ምሥዋዕ ፡ ወፈጺሞሙ ፡ ግብረ ፡ ቅዳሴ ፡ ተመጠዉ ፡ ምሥጢራተ ፡ ቅድሳት ። ወእምድኅረ ፡ ዝንቱ ፡ ኀለዩ ፡ ካህናት ፡ ማኅሌተ ፡ አኰቴት ፡ እንዘ ፡ ያዜክሩ ፡ መዊኦተ ፡ ዝንቱ ፡ ንጉሥ. |

| 46 | (Conti Rossini 1907, p. 98). For an overview on this tradition, its link with the church in question, and an examination of its development over time, see (Munro-Hay 2006). |

| 47 | Here, we should distinguish between the overall area inhabited by the Betä Ǝsraʾel as indicated in Figure 1, and the territory within this overall area in which they maintained their political autonomy. What the scope of the churches would likely indicate is the scope of the territories which were formerly part of Betä Ǝsraʾel political autonomy and had come under direct Solomonic control as a result of a given campaign. |

| 48 | For suggestions regarding their general location, based on an examination of the geography of Śärṣä Dǝngǝl’s campaigns against the autonomous Betä Ǝsraʾel, see (Kribus, forthcoming b). |

References

- Abbink, Jon. 1990. The Enigma of Beta Esra’el Ethnogenesis. An Anthro-Historical Study. Cahiers D’études Africaines 120: 397–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basset, René. 1881. Études sur l’histoire d’Éthiopie. Première parte. Chronique Éthiopienne d’après un manuscript de la Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris. Journal Asiatique 18: 93–183, 285–389. [Google Scholar]

- Basset, René. 1882. Études sur l’histoire d’Éthiopie. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale. [Google Scholar]

- Beaucamp, Joëlle, Françoise Briquel-Chatonnetet, and Christian J. Robin, eds. 2010. Le massacre de Najrận II. Juifs et Chrétiens en Arabie aux Ve et VIe siècles. Regards croisés sur les sources. Paris: Association des amis du Centre d’histoire et civilisation de Byzanc. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Adam H., and Annette Yoshiko Reed, eds. 2007. The Ways That Never Parted. Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Becket, Ian F.W. 2014. Military Commemoration in Britian: A Pre-History. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 92: 147–59. [Google Scholar]

- Beckingham, Charles Fraser. 1951. A Note on the Topography of Ahmad Gran’s Campaign in 1542. Journal of Semitic Studies 4: 362–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beguinot, Francesco. 1901. La Cronaca Abbreviata d’Abissinia. Nuova versione dall’Etiopico e commento. Roma: Tip, Della Casa Edit. Italiana. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, LaVerle B. 1995. Architecture and Kingship: The Significance of Gondar-Style Architecture. Northeast African Studies 2: 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, LaVerle B. 2005. Gondär: Gondär-style architecture. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 843–45. [Google Scholar]

- Binns, John. 2017. The Orthodox Church of Ethiopia. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Boas, Adrian J. 2001. Jerusalem in the Time of the Crusades. Society, Landscape and Art in the Holy City Under Frankish Rule. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bosc-Tiessé, Claire. 2005. Daga Ǝsṭifanos. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bosc-Tiessé, Claire. 2007. Narga Śǝllase. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 3, pp. 1148–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bowersock, Glen W. 2013. The Throne of Adulis. Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, James. 1790. Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile in the Years 1768, 1769, 1770, 1771, 1772 and 1773. 5 vols. Edinburgh: R. Ruthven. [Google Scholar]

- Chaillot, Christine. 2002. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church Tradition. A Brief Introduction to its Life and Spirituality. Paris: Inter-Orthodox Dialogue. [Google Scholar]

- Conti Rossini, Carlo. 1907. Historia regis Sarṣa Dengel (Malak Sagad). Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium 21. Paris: E Typographeo Reipublicae. [Google Scholar]

- Corinaldi, Michael. 2005. Yahadūt ʾEtiyopiyah. Zehūt w-Masoret [Ethiopian Jewry. Identity and Tradition]. Jerusalem: Rubin Mass Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Crummy, Donald. 2014. Yosṭos. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Alessandro Bausi and Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 5, pp. 97–98. [Google Scholar]

- Cuffel, Alexandra, and Ophira Gamliel. 2018. Historical Engagements and Interreligious Encounters. Jews and Christians in Premodern and Early Modern Asia and Africa. Entangled Religions 6: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cytryn, Katia. 2009. The Umayyad Mosque of Tiberias. Muqarnas 26: 37–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, Abraham. 2023. Milḥamot ha-Hiśardūt šel Yehūdey Mamleḵet Presṭer John be-Sof Yemey ha-Beynayim ʿal-pi Meqorot ʿIvriyim [The Wars for Survival of the Jews of the Kingdom of Prester John at the End of the Middle Ages According to Hebrew Sources]. In ʿIyūnim be-Toldot Beteh Yiśraʾel. Ha-Historiyah šel Yehūdey ʾEtiyopiyah [Studies in Beta Israel Heritage. 1. History of the Jews of Ethiopia]. Edited by Simcha Getahune and Tamar Garden. Jerusalem: Ethiopian Jewry Heritage Center and Pardes, pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Dege-Müller, Sophia. 2020. The Monastic Genealogy of Hoḫwärwa Monastery—A Unique Witness of Betä Ǝsraʾel Historiography. Aethiopica 23: 57–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dege-Müller, Sophia, and Bar Kribus. 2021. The Veneration of St. Yared—A Multireligious Landscape Shared by Ethiopian Orthodox Christians and the Betä Ǝsraʾel (Ethiopian Jews). In Geographies of Encounter. The Making and Unmaking of Multi-Religious Spaces. Edited by Marian Burchardt and Maria Chiara Giorda. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 255–80. [Google Scholar]

- Derat, Marie-Laure. 2003. Le domaine des rois éthiopiens, 1270–1527: Espace, pouvoir et monachisme. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne. [Google Scholar]

- Deresse Ayenachew. 2020. Territorial Expansion and Administrative Evolution under the “Solomonic” Dynasty. In A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea. Edited by Samantha Kelly. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 57–85. [Google Scholar]

- Detoraki, Marina, and Joëlle Beaucamp, trans. 2007. Le martyre de Saint Aréthas et de ses compagnons. Paris: Association des amis du Centre d’histoire et civilisation de Byzance. [Google Scholar]

- Diprose, Ronald E. 2000. Israel and the Church: The Origins and Effects of Replacement Theology. Waynesboro: Authentic Media. [Google Scholar]

- di Salvo, Mario. 1999. Churches of Ethiopia. The Monastery of Nārgā Śellāsē. Milano: Skira Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski, Franz Amadeus. 1983. Tanasee 106: Eine Chronik der Herrscher Äthiopiens. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Faü, Jean-François. 2005. L’image des juifs dans l’art chrétien medieval. Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose. [Google Scholar]

- Foti, Concetta. 1941. La Cronica abbreviate dei Re d’Abissinia in un manoscritto di Dabra Berhān di Gondar. Rassegna di Studi Etiopici 1: 87–123. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen, Paula, and Oded Irshai. 2006. Christian Anti-Judaism: Polemics and Policies. In The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 4, The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period. Edited by Steven T. Katz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 977–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch, Emmanuel. 2018. The Origins and Meanings of the Ethiopian Circular Church: Fresh Explorations. In Tomb and Temple. Re-Imagining the Sacred Buildings of Jerusalem. Edited by Robin Griffith-Jones and Eric Fernie. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, pp. 267–93. [Google Scholar]

- Gajda, Iwona. 2009. Le royaume de Ḥimyar à l’époque monothéiste. L’histoire de l’Arabie du Sud ancienne de la fin du IVe siècle de l’ère chrétienne jusqu’à l’avènement de l’Islam. Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. [Google Scholar]

- Guidetti, Mattia. 2016. In the Shadow of the Church. The Building of Mosques in Early Medieval Syria. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Habtemichael Kidane. 2011. Qəne. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig and Alessandro Bausi. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 4, pp. 283–85. [Google Scholar]

- HaCohen, Ran. 2009. Kǝḇod ha-Melaḵim. Ha-ʾEpos ha-Leʾumi ha-ʾEtiyopi. [Kebra Nagast. Translated from Geʿez, annotated and Introduced by Ran HaCohen]. Tel Aviv: Haim Rubin Tel Aviv University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Halévy, Joseph. 1907. La guerre de Sarṣa Děngěl contre les Falachas. Texte Éthiopien. Extrait des Annales de Sarṣa Děngěl, roi d’Éthiopie (1563–1597). Manuscrit de la Bibliotheque Nationale nº 143. Fol. 159 rº, col. 2—fol. 171 vº, col. I. Paris: E. Leroux. [Google Scholar]

- Heldman, Marilyn E. 2003. Church Buildings. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 1, pp. 737–40. [Google Scholar]

- Heldman, Marilyn E. 2011. Tabot. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig and Alessandro Bausi. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 4, pp. 802–4. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac, Ephraim. 2013. The Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahïdo Church. Trenton: Red Sea Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Steven. 1984. The Monastic Holy Man and the Christianization of Early Solomonic Ethiopia. Weisbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Steven. 1992. The Beta Israel (Falasha) in Ethiopia. From the Earliest Times to the Twentieth Century. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Steven. 2005. Däbr. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Steven. 2007. Monasteries. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 3, pp. 987–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Steven. 2011. Solomonic Dynasty. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig and Alessandro Bausi. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 4, pp. 688–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kribus, Bar. 2022. Jewish-Christian Interaction in Ethiopia as Reflected in Sacred Geography: Expressing Affinity with Jerusalem and the Holy Land and Commemorating the Betä Ǝsraʾel–Solomonic Wars. Religions 13: 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kribus, Bar. 2023. The Campaign of the Solomonic Monarch Yəsḥaq (1414–1429/30) as a Turning Point in Betä Ǝsraʾel History: Its Commemoration in Solomonic and Betä Ǝsraʾel Sources and Holy Sites. Aethiopica 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kribus, Bar. 2024. A Re-Examination of the Origins and Early Development of Ethiopian Concentric Prayer Houses: Tracing an Architectural Concept from the Roman and Byzantine East to Islamic and Crusader Jerusalem to Solomonic Ethiopia. Religions 15: 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kribus, Bar. Forthcoming a. The Historical Geography of Betä Ǝsraʾel (Ethiopian Jewish) Involvement in the Conflict between the Solomonic Kingdom and the Forces of Imām Aḥmad b. Ibrāhīm al-Ġāzī. Aethiopica.

- Kribus, Bar. Forthcoming b. Jewish Autonomy in Conflict with Christians in Northern Ethiopia. The Gideonite Dynasty and the Solomonic Kingdom. Leeds: Arc Humanities Press.

- Kribus, Bar. Forthcoming c. The Battlefields of the ‘Ten Lost Tribes’ in Ethiopia. Tracing the Geographical and Material Culture Aspects of the Wars between the Betä Ǝsraʾel (Ethiopian Jews) and the Christian Solomonic Kingdom. In Sambatyon: The Mythical Boundary in Time and Space. Edited by Moti Benmelech and Daniel Stein Kokin. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Kribus, Bar, and Elad Wexler. Forthcoming. The Last Campaign of the Kingdom of the Gideonites. New Insight Following a First Visit to Sägänät, the Capital of Jewish Rule in the Sǝmen Mountains. Peʿamim: Studies in Oriental Jewry.

- Kribus, Bar, and Sophia Dege-Müller. 2022. St. Yared in the Sǝmen Mountains of Northern Ethiopia: The Ethiopian Orthodox and Betä Ǝsraʾel (Ethiopian Jewish) Religious Sites. Afriques, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Kribus, Bar, Zaroui Pogossian, and Alexandra Cuffel. 2024. Material Encounters between Jews and Christians: From the Silk and Spice Routes to the Highlands of Ethiopia. Leeds: ARC Humanities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leisten, Thomas. 1996. Mashhad Al-Nasr: Monuments of War and Victory in Medieval Islamic Art. Muqarnas 13: 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslau, Wolf. 1991. Comparative Dictionary of Geʿez (Classical Ethiopic). Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, Sara. 2014. Dark Mirror: The Medieval Origins of Anti-Jewish Iconography. New York: Metropolitan Books. [Google Scholar]

- Marrassini, Paolo. 2007. Kǝbrä nägäśt. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 3, pp. 364–68. [Google Scholar]

- Moberg, Axel, ed. 1924. The Book of the Himyarites. Fragments of a Hitherto Unknown Syriac Work. Lund: C.W.K. Gleerup. [Google Scholar]

- Munro-Hay, Stuart. 1991. Aksum. An African Civilization of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Munro-Hay, Stuart. 2006. The Quest for the Ark of the Covenant. A True History of the Tablets of Moses. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Pankhurst, Richard. 2005. Däbrä Bǝrhan Śǝllase. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, Esteves. 1900. Chronica de Susenyos, Rei de Ethiopia. Vol. 2, Traduccãu e notas. Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional. [Google Scholar]

- Perruchon, Jules François Célestin. 1896. Notes pour l’histoire d’Éthiopie. Règne de Sarṣa-Dengel ou Malak-Sagad 1er (1563–1597). Revue Semitique 4: 177–85. [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson, David W. 2009. Ancient Churches of Ethiopia. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson, David W. 2012. Foundations of an African Civilisation. Aksum and the Northern Horn 1000 BC—AD 1300. Rochester: James Currey, Boydell & Brewer Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Piovanelli, Pierluigi. 2013. The Apocryphal Legitimation of a ‘Solomonic’ Dynasty in the Kǝbrä Nägäśt—A Reappraisal. Aethiopica 16: 8–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogossian, Zaroui. 2017. Locating Religion, Controlling Territory: Conquest and Legitimation in Late Ninth-Century Vaspurakan and its Interreligious Context. In Locating Religions. Contact, Diversity and Translocality. Edited by Reinhold F. Glei and Nikolas Jaspert. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 173–233. [Google Scholar]

- Quirin, James. 1992. The Evolution of the Ethiopian Jews. A History of the Beta Israel (Falasha) to 1920. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quirin, James. 2005. Gedewon. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2, p. 730. [Google Scholar]

- Revel-Neher, Elisabeth. 1992. The Image of the Jew in Byzantine Art. Oxford: Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robin, Christian J. 2004. Himyar et Israël. Comptes-rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 148: 831–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, Hagar. 1999. The Hyena People. Ethiopian Jews in Christian Ethiopia. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon Gebreyes Beyene. 2015. The Chronicle of Emperor Gälawdewos (1540–1559): A Source on Ethiopia’s Medieval Historical Geography. In Essays in Ethiopian Manuscript Studies. Proceedings of the International Conference Manuscripts and Texts, Languages and Contexts: The Transmission of Knowledge in the Horn of Africa. Hamburg, 17–19 July 2014, Supplement to Aethiopica 4. Edited by Alessandro Bausi, Alessandro Gori, Denis Nosnistin and Eugenia Sokolinski. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 109–19. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon Gebreyes Beyene. 2016. The Chronicle of King Gälawdewos (1540–1559): A Critical Edition with Annotated Translation. Ph.D. dissertation, Hamburg University, Hamburg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon Gebreyes Beyene. 2019. The Tradition and Development of Ethiopic Chronicle Writing (Sixteenth–Seventeenth Centuries): Production, Source, and Purpose. In Time and history in Africa. Edited by Alessandro Bausi, Alberto Camplani and Stephen Emmel. Milan: Biblioteca Ambrosiana, pp. 145–60. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon Gebreyes Beyene. 2023. Representations of the History of Beta ʾƎsrāʾel (Ethiopian Jews) in the Royal Chronicle of King Śarḍa Dǝngǝl (r.1563–1597): Censorship, a Philological and Historical Commentary. Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies Bulletin 9: 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Taddesse Tamrat. 1972. Church and State in Ethiopia 1270–1527. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waldman, Menachem. 1989. Meʿever le-Naharey Kūš. Yehūdey ʾEtiyopiyah ve-ha-ʿAm ha-Yehūdi. [Beyond the Rivers of Ethiopia. The Jews of Ethiopia and the Jewish People]; Tel Aviv: Ministry of Defense.

- Waldman, Menachem. 2018. Divrey Aba Yiẓḥaq. [The Words of Abba Yǝsḥaq]. Peʿamim 154–55: 279–98. [Google Scholar]

- Weninger, Stefan. 2005. Geʿez. In Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Edited by Siegbert Uhlig. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 2, pp. 732–35. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).